15. Colonialismo y Conciencia

Feliz fin de Semana Santa, everybody. As a (late) Easter update, I thought I'd write something on TTL's counterpart to one of OTL Christianity's more inspiring episodes (which contains a few hints as to where things are going in the near future ITTL).

The Leyes de León, passed in 1510, were intended to regulate the practice of encomienda in the Indies and to protect the Indios under Spanish jurisdiction from harm. However, given the sheer expanse of the Indies (the isle of Cuba alone is greater in width than the Iberian peninsula) and the consequent lack of royal oversight meant that these Leyes could only function as a stopgap: the Leyes, despite its apparent humanitarian concern, still treated the Indios as a people who required close surveillance, obeisance to the Spanish, and forced relocation more than anything else, while the provisions made for the fair treatment of the Indios under Spanish rule also failed to specify how Indios beyond the pale were to be treated and what casus belli was required to war against them. The efforts taken to rectify this situation and the debate it sparked would mark one of the first major attempts by an imperial system to consider the ethics of its imperialism, and then, in turn, attempt to find a solution that satisfied the consciences of its most conscientious subjects.

La encomienda

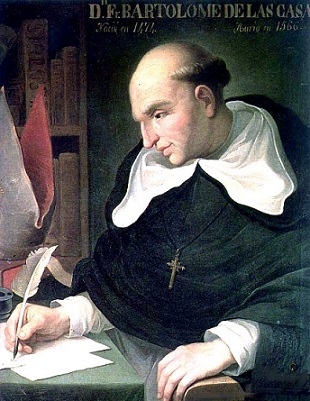

The Dominicans were the first to oppose the brutalization of the Indios. Under Fray Pedro de Córdoba, the vicar of the first band of Dominicans in the Americas, a pamphleteering campaign and series of sermons delivered in Santo Domingo and the other towns of La Española and Cuba began in late 1510, with the landmark event being the sermons given by the fiery Antonio de Montesinos in early 1511, who railed against his Spanish audience, accusing them of acting in blatant violation of their Spanish heritage, their Christian faith, and even their basic senses in treating the Indios as subhuman. The most ardent voice that arose to challenge the widespread treatment of the Indios as second-class citizens or worse was a Dominican friar by the name of Bartolomé de Las Casas. Arriving in Santo Domingo with his father in 1502 (the same year, symbolically, that Diego Colón died at sea), Las Casas had been one of the first priests ordained in the Americas, and participated in the conquests of La Española and Cuba - gaining encomiendas on both islands and living as a gentleman cleric. Las Casas was apparently a benevolent encomendero (and many such encomenderos did exist), yet the financial aspects of the encomienda prevented Las Casas from focusing his energies on the catechization of the Indios entrusted to him. Whether or not Las Casas was aware of the advocacy undertaken by Pedro de Córdoba or Antonio de Montesinos is unknown, but we do know that the dissonance between Las Casas’ priestly duties and his status as a quasi-slave owner began to work towards a crisis of conscience, which came to a head in 1512 [1]. Partaking in campaigns against the uprisings of Cuba’s subjugated Ciboney and Guanajatabey Indios, and witnessing the squabbles of Cuba’s first three captains general - Francisco de Montejo, Diego Velázquez, and Juan de Grijalva - over lands and Indio labor, Las Casas began to intensify his vituperation of the Spaniards and their actions in the Indies. Having accumulated a greater sensitivity to the humanity of the Indios, Las Casas remarked that “these rapacious captains that call themselves Spaniards … are no less base than the pagans that they lord over, bartering over the poor Indios in the fashion of what might be seen on the streets of Sevilla over melons or pomegranates.” In regards to the Spanish military activity against the Indios that he had taken part in as a chaplain, Las Casas also related that he "saw here cruelty on a scale no living being has ever seen or expects to see."

Bartolomé de Las Casas

Coordinating with Pedro de Córdoba, Las Casas made plans to appeal directly to the Crown. In early 1513, Las Casas had arrived in Sevilla and, after three months waiting, was able to get his much desired audience with the Catholic Monarchs. While Isabel of Castile was ailing, she upheld her previous concern for her Indio subjects and agreed to assemble a committee to be sent to the Indies to address the matter. As to which religious order would comprise this committee, Las Casas pushed for the Dominicans, but, given Isabel’s confidence in the Franciscans and some determined stonewalling from the head of the Council of the Indies, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca (who was an encomendero), the Franciscans were chosen. The problem with this arrangement was that the Franciscans, despite their commitment in the evangelization of the Indios, were also committed opponents of the Dominicans in the latter’s defense of the Indios’ full humanity. Most Franciscan missionaries in the New World at the time treated the Indios as perpetual children (citing their primitive way of life), who should be baptized, taught the basics of the Gospel (often very superficially), and then be allowed to fulfill the role that God had so obviously intended for them - which in their eyes was as lifetime residents of a mission or as laborers under an encomendero. This was a difficult position to oppose - the Franciscan position satisfied the requirement for evangelization and seemed also to be opposed to excessive cruelty towards the Indios, all while allowing the very profitable status quo to continue. However, the two former aspects were hardly true, and the Dominicans (who Las Casas formally joined in 1517) continued their protest. Luckily, the conquest of the Aztecs, begun in 1516, revealed the Indios to be quite capable of all the identifying aspects of ordered civilization, and the debate over their humanity was once again pushed to the fore, leading to a meeting between Las Casas and the young King Miguel in 1519. Las Casas, who had spent the last five years putting out a body of truly voluminous body of works in the defense of the Indios, had also spent most of the year prior to his meeting with Miguel studying at the Colegio de San Gregorio in Valladolid, a Dominican-run establishment.

Las Casas and those like minded would find their position vindicated by the prevailing school of Spanish thought at the time, that of the primarily Dominican “Escuela de Salamanca,” which included such thinkers as Francisco de Vitoria and Domingo de Soto - often considered the founders of international law. The Escuela de Salamanca prevailed over not only the University of Salamanca - the oldest, largest, and most prestigious center of higher learning in Castile - but also over the Universities of Braga and Coimbra [2] in Portugal. Following a Scholastic, Thomist rubric, the Escuela de Salamanca more or less promulgated an understanding of law as differentiated between local, customary law (as is to be found in individual kingdoms and principalities) and “natural” law - which was the law of man across the board, regardless of physical or mental composition. The Escuela de Salamanca predicated this natural law on what could be readily observed or what could be deduced through a biblical lens (in regards to Aristotelianism, through a Thomistic lens), and from this it followed that all men deserve the right to their own “dominion” (meaning both a sovereign, self-determining polity of their own, as well as individual freedom and self-determination), and therefore slavery is an unnatural, man-made institution which is to be reserved only for those who are “enemies of the faith” who are captured in battle, and those who forfeit their dominion either through a sufficiently heinous act or by willfully surrendering it. Likewise, a truly “just” war was only one that could fulfill a number of prerequisites that were noticeably absent from the campaigns of the conquistadores - namely, a just war cannot be waged as a private enterprise, it can only follow sufficient provocation, and it must proceed without wanton brutality.

La Universidad de Salamanca

The debate would quickly shift in Las Casas’ favor on two fronts. Firstly, Miguel, who was opposed to the enslavement of the Indios (and also of Sub-Saharan Africans) on the grounds that it harmed the chances of evangelization, was sympathetic to Las Casas’ cause. Given the incessant criticism of las Casas from nearly every side, however, Miguel wished for Las Casas to prove, firstly, that a Spanish colony in the Americas could subsist without Indio labor. Las Casas, fearing opposition from the encomenderos (who might seek to sabotage his experiment), had to choose a location well beyond their reach, and chose the banks of the Río de La Plata. Departing with 240 peasants from Castile and Aragon, as well as with 12 other Dominicans, Las Casas’ expedition arrived at La Plata in December of 1520. Despite some troubling encounters with the nearby Indios, irregularity in return voyages, and difficulty in adapting to this new land, Las Casas’ colony, which he dubbed “Bahía del Espíritu Santo,” survived - primarily due to the climate and soil, both of which were excellent for European Spaniards. Espíritu Santo would encounter a plethora of hardships later on, but Las Casas - against all odds - had made his point. Miguel designated Las Casas the “Protector de los Indios” in 1522 - which would be an independent, auxiliary position to the Council of the Indies - and would write into law that the Indios no longer required an encomendero to organize or administer their communities, although every Indio community was still required to have present one resident Spaniard and one church, and that every governor and captain general was required to settle no less than 100 Spanish families in his governorate or captaincy during his tenure. The encomienda was not abolished, by any means, but an important step had been taken against it.

Miguel, however, was very much opposed to restricting warfare against the Indios - at least at first. He had been fed many lurid tales of human sacrificing flesh-eaters and other such pagan idolatry by representatives of Cortés and his cohorts (who were there to justify their superiors’ unsanctioned conquest), and he also felt that raising questions over the ethics of warfare against the heathen would affect his ongoing crusade in North Africa. While such concerns never called the African crusade into question (given the Muslims’ status as “enemies of the faith”), Miguel appreciated the proselytizing effects that came with military conquest and political control. Nonetheless, it eventually became apparent to Miguel that the Spaniards’ manner of proliferating themselves across the Americas was causing more harm than good. After hearing the news of three Basques establishing pseudo-kingdoms in the former Inca empire, Miguel was convinced that a formal limitation on Spanish conquests was necessary to prevent his freebooting subjects from carving off pieces of what should be royal possessions. While court jurists and the representatives of encomenderos pushed for the drafting of a document to be read to the Indios - explaining therein Spain’s right to the Americas as provided in the Papal bull Inter caetera [3] and using such as a sufficient casus belli - it was ultimately decided that Indio peoples could only be warred against if 1) they had attacked Spanish subjects, 2) they rejected or killed a Christian missionary, or 3) if there was found amongst them evidence of human sacrifice or cannibalism. These provisions, along with those pronounced in 1522, would be compiled and written into law as part of the “Protecciones de Cartagena” [4] - a corollary to the Leyes de León.

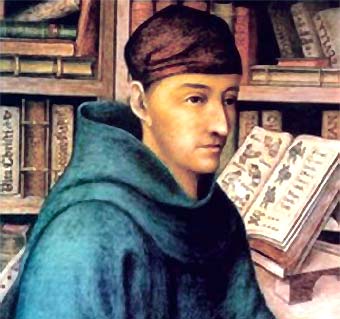

Bernardino de Sahagún

The second development in favor of Indio rights came from within the Franciscans. Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan friar working in Nueva Castilla, had become disillusioned with the superficial conversion of the Indios under Spanish rule after years spent immersed in their society and researching their history. Sahagún believed that the Indios could not be truly brought to the faith (without heavy syncretism, at least) unless there were efforts made to understand their culture and language, and for this reason it was necessary to form an Indio clergy. Sahagún would spend most of his life urging his fellow Franciscans to learn the languages of the Americas and founding and maintaining universities intended to educate the Indio elite in the fashion of an authentic European seminary. The Indio universities founded by Sahagún and his colleagues - the Colegio de San Isidoro in México-Tenochtitlan (1528), the Colegio de San Gregorio in Santiago del Ríochambo (1536), the Colegio de San Juan Damasceno in Cusco (1537), the Colegio de San Agustín in San Martín de Limac (1539), the Colegio de San Roque in San Germán de Guatemala (1541), and the Colegio de Santa Catalina in Santiago de Bogotá (1542) - would all receive royal endowment in 1552 as part of Juan Pelayo’s Leyes Nuevas, and would be instrumental in translating a great number of Indio texts - some of which contained a wealth of herbological information, and led to the discovery of quinine and its antimalarial properties in the 1570s. The disparity between Sahagún’s approach to evangelization and the approach preferred by most of the Franciscans in the New World would eventually lead to the formation of a new order in 1542 - “La Fraternidad Catequética de San Gregorio,” popularly known as the Bernardines in Spain proper and the Gregorians overseas (also alternatively known as the Catequistas).

El Colegio de San Isidoro

Las Casas and Sahagún’s advocacy of the indigenous peoples under Spain’s colonial rule would be mirrored by numerous others, such as Juan de Zumárraga, the first bishop of Cartagena and later of Santiago de Bogotá, Tomás de Berlanga, who trekked across the Tierra de Pascua (and proved the Isla Florida was not, in fact, an island), Francisco de Jasso [5], the “Apostle of the Chichimecs,” Domingo Betanzos, the first bishop of San Germán de Guatemala, and the Portuguese missionaries Francisco Álvares and Simão Rodrigues, who preached in Sub-Saharan Africa and the East Indies, respectively. Las Casas himself would be named the bishop of Michoacán and auxiliary bishop of the Ilhas Miguelinhas [6], while Sahagún would end his days as the bishop of México-Tenochtitlan.

[1] Two years earlier than IOTL

[2] IOTL the university system in Portugal had no set, central location until the 1530s when João cemented it at Coimbra - here it's been split into two colleges at Brava and Coimbra

[3] What would have been TTL's Requirimiento

[4] Miguel was at Cartagena at the time

[5] St Francis Xavier

[6] OTL's Philippines

~ Colonialismo y Conciencia ~

The Leyes de León, passed in 1510, were intended to regulate the practice of encomienda in the Indies and to protect the Indios under Spanish jurisdiction from harm. However, given the sheer expanse of the Indies (the isle of Cuba alone is greater in width than the Iberian peninsula) and the consequent lack of royal oversight meant that these Leyes could only function as a stopgap: the Leyes, despite its apparent humanitarian concern, still treated the Indios as a people who required close surveillance, obeisance to the Spanish, and forced relocation more than anything else, while the provisions made for the fair treatment of the Indios under Spanish rule also failed to specify how Indios beyond the pale were to be treated and what casus belli was required to war against them. The efforts taken to rectify this situation and the debate it sparked would mark one of the first major attempts by an imperial system to consider the ethics of its imperialism, and then, in turn, attempt to find a solution that satisfied the consciences of its most conscientious subjects.

La encomienda

The Dominicans were the first to oppose the brutalization of the Indios. Under Fray Pedro de Córdoba, the vicar of the first band of Dominicans in the Americas, a pamphleteering campaign and series of sermons delivered in Santo Domingo and the other towns of La Española and Cuba began in late 1510, with the landmark event being the sermons given by the fiery Antonio de Montesinos in early 1511, who railed against his Spanish audience, accusing them of acting in blatant violation of their Spanish heritage, their Christian faith, and even their basic senses in treating the Indios as subhuman. The most ardent voice that arose to challenge the widespread treatment of the Indios as second-class citizens or worse was a Dominican friar by the name of Bartolomé de Las Casas. Arriving in Santo Domingo with his father in 1502 (the same year, symbolically, that Diego Colón died at sea), Las Casas had been one of the first priests ordained in the Americas, and participated in the conquests of La Española and Cuba - gaining encomiendas on both islands and living as a gentleman cleric. Las Casas was apparently a benevolent encomendero (and many such encomenderos did exist), yet the financial aspects of the encomienda prevented Las Casas from focusing his energies on the catechization of the Indios entrusted to him. Whether or not Las Casas was aware of the advocacy undertaken by Pedro de Córdoba or Antonio de Montesinos is unknown, but we do know that the dissonance between Las Casas’ priestly duties and his status as a quasi-slave owner began to work towards a crisis of conscience, which came to a head in 1512 [1]. Partaking in campaigns against the uprisings of Cuba’s subjugated Ciboney and Guanajatabey Indios, and witnessing the squabbles of Cuba’s first three captains general - Francisco de Montejo, Diego Velázquez, and Juan de Grijalva - over lands and Indio labor, Las Casas began to intensify his vituperation of the Spaniards and their actions in the Indies. Having accumulated a greater sensitivity to the humanity of the Indios, Las Casas remarked that “these rapacious captains that call themselves Spaniards … are no less base than the pagans that they lord over, bartering over the poor Indios in the fashion of what might be seen on the streets of Sevilla over melons or pomegranates.” In regards to the Spanish military activity against the Indios that he had taken part in as a chaplain, Las Casas also related that he "saw here cruelty on a scale no living being has ever seen or expects to see."

Bartolomé de Las Casas

Coordinating with Pedro de Córdoba, Las Casas made plans to appeal directly to the Crown. In early 1513, Las Casas had arrived in Sevilla and, after three months waiting, was able to get his much desired audience with the Catholic Monarchs. While Isabel of Castile was ailing, she upheld her previous concern for her Indio subjects and agreed to assemble a committee to be sent to the Indies to address the matter. As to which religious order would comprise this committee, Las Casas pushed for the Dominicans, but, given Isabel’s confidence in the Franciscans and some determined stonewalling from the head of the Council of the Indies, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca (who was an encomendero), the Franciscans were chosen. The problem with this arrangement was that the Franciscans, despite their commitment in the evangelization of the Indios, were also committed opponents of the Dominicans in the latter’s defense of the Indios’ full humanity. Most Franciscan missionaries in the New World at the time treated the Indios as perpetual children (citing their primitive way of life), who should be baptized, taught the basics of the Gospel (often very superficially), and then be allowed to fulfill the role that God had so obviously intended for them - which in their eyes was as lifetime residents of a mission or as laborers under an encomendero. This was a difficult position to oppose - the Franciscan position satisfied the requirement for evangelization and seemed also to be opposed to excessive cruelty towards the Indios, all while allowing the very profitable status quo to continue. However, the two former aspects were hardly true, and the Dominicans (who Las Casas formally joined in 1517) continued their protest. Luckily, the conquest of the Aztecs, begun in 1516, revealed the Indios to be quite capable of all the identifying aspects of ordered civilization, and the debate over their humanity was once again pushed to the fore, leading to a meeting between Las Casas and the young King Miguel in 1519. Las Casas, who had spent the last five years putting out a body of truly voluminous body of works in the defense of the Indios, had also spent most of the year prior to his meeting with Miguel studying at the Colegio de San Gregorio in Valladolid, a Dominican-run establishment.

Las Casas and those like minded would find their position vindicated by the prevailing school of Spanish thought at the time, that of the primarily Dominican “Escuela de Salamanca,” which included such thinkers as Francisco de Vitoria and Domingo de Soto - often considered the founders of international law. The Escuela de Salamanca prevailed over not only the University of Salamanca - the oldest, largest, and most prestigious center of higher learning in Castile - but also over the Universities of Braga and Coimbra [2] in Portugal. Following a Scholastic, Thomist rubric, the Escuela de Salamanca more or less promulgated an understanding of law as differentiated between local, customary law (as is to be found in individual kingdoms and principalities) and “natural” law - which was the law of man across the board, regardless of physical or mental composition. The Escuela de Salamanca predicated this natural law on what could be readily observed or what could be deduced through a biblical lens (in regards to Aristotelianism, through a Thomistic lens), and from this it followed that all men deserve the right to their own “dominion” (meaning both a sovereign, self-determining polity of their own, as well as individual freedom and self-determination), and therefore slavery is an unnatural, man-made institution which is to be reserved only for those who are “enemies of the faith” who are captured in battle, and those who forfeit their dominion either through a sufficiently heinous act or by willfully surrendering it. Likewise, a truly “just” war was only one that could fulfill a number of prerequisites that were noticeably absent from the campaigns of the conquistadores - namely, a just war cannot be waged as a private enterprise, it can only follow sufficient provocation, and it must proceed without wanton brutality.

La Universidad de Salamanca

The debate would quickly shift in Las Casas’ favor on two fronts. Firstly, Miguel, who was opposed to the enslavement of the Indios (and also of Sub-Saharan Africans) on the grounds that it harmed the chances of evangelization, was sympathetic to Las Casas’ cause. Given the incessant criticism of las Casas from nearly every side, however, Miguel wished for Las Casas to prove, firstly, that a Spanish colony in the Americas could subsist without Indio labor. Las Casas, fearing opposition from the encomenderos (who might seek to sabotage his experiment), had to choose a location well beyond their reach, and chose the banks of the Río de La Plata. Departing with 240 peasants from Castile and Aragon, as well as with 12 other Dominicans, Las Casas’ expedition arrived at La Plata in December of 1520. Despite some troubling encounters with the nearby Indios, irregularity in return voyages, and difficulty in adapting to this new land, Las Casas’ colony, which he dubbed “Bahía del Espíritu Santo,” survived - primarily due to the climate and soil, both of which were excellent for European Spaniards. Espíritu Santo would encounter a plethora of hardships later on, but Las Casas - against all odds - had made his point. Miguel designated Las Casas the “Protector de los Indios” in 1522 - which would be an independent, auxiliary position to the Council of the Indies - and would write into law that the Indios no longer required an encomendero to organize or administer their communities, although every Indio community was still required to have present one resident Spaniard and one church, and that every governor and captain general was required to settle no less than 100 Spanish families in his governorate or captaincy during his tenure. The encomienda was not abolished, by any means, but an important step had been taken against it.

Miguel, however, was very much opposed to restricting warfare against the Indios - at least at first. He had been fed many lurid tales of human sacrificing flesh-eaters and other such pagan idolatry by representatives of Cortés and his cohorts (who were there to justify their superiors’ unsanctioned conquest), and he also felt that raising questions over the ethics of warfare against the heathen would affect his ongoing crusade in North Africa. While such concerns never called the African crusade into question (given the Muslims’ status as “enemies of the faith”), Miguel appreciated the proselytizing effects that came with military conquest and political control. Nonetheless, it eventually became apparent to Miguel that the Spaniards’ manner of proliferating themselves across the Americas was causing more harm than good. After hearing the news of three Basques establishing pseudo-kingdoms in the former Inca empire, Miguel was convinced that a formal limitation on Spanish conquests was necessary to prevent his freebooting subjects from carving off pieces of what should be royal possessions. While court jurists and the representatives of encomenderos pushed for the drafting of a document to be read to the Indios - explaining therein Spain’s right to the Americas as provided in the Papal bull Inter caetera [3] and using such as a sufficient casus belli - it was ultimately decided that Indio peoples could only be warred against if 1) they had attacked Spanish subjects, 2) they rejected or killed a Christian missionary, or 3) if there was found amongst them evidence of human sacrifice or cannibalism. These provisions, along with those pronounced in 1522, would be compiled and written into law as part of the “Protecciones de Cartagena” [4] - a corollary to the Leyes de León.

Bernardino de Sahagún

The second development in favor of Indio rights came from within the Franciscans. Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan friar working in Nueva Castilla, had become disillusioned with the superficial conversion of the Indios under Spanish rule after years spent immersed in their society and researching their history. Sahagún believed that the Indios could not be truly brought to the faith (without heavy syncretism, at least) unless there were efforts made to understand their culture and language, and for this reason it was necessary to form an Indio clergy. Sahagún would spend most of his life urging his fellow Franciscans to learn the languages of the Americas and founding and maintaining universities intended to educate the Indio elite in the fashion of an authentic European seminary. The Indio universities founded by Sahagún and his colleagues - the Colegio de San Isidoro in México-Tenochtitlan (1528), the Colegio de San Gregorio in Santiago del Ríochambo (1536), the Colegio de San Juan Damasceno in Cusco (1537), the Colegio de San Agustín in San Martín de Limac (1539), the Colegio de San Roque in San Germán de Guatemala (1541), and the Colegio de Santa Catalina in Santiago de Bogotá (1542) - would all receive royal endowment in 1552 as part of Juan Pelayo’s Leyes Nuevas, and would be instrumental in translating a great number of Indio texts - some of which contained a wealth of herbological information, and led to the discovery of quinine and its antimalarial properties in the 1570s. The disparity between Sahagún’s approach to evangelization and the approach preferred by most of the Franciscans in the New World would eventually lead to the formation of a new order in 1542 - “La Fraternidad Catequética de San Gregorio,” popularly known as the Bernardines in Spain proper and the Gregorians overseas (also alternatively known as the Catequistas).

El Colegio de San Isidoro

Las Casas and Sahagún’s advocacy of the indigenous peoples under Spain’s colonial rule would be mirrored by numerous others, such as Juan de Zumárraga, the first bishop of Cartagena and later of Santiago de Bogotá, Tomás de Berlanga, who trekked across the Tierra de Pascua (and proved the Isla Florida was not, in fact, an island), Francisco de Jasso [5], the “Apostle of the Chichimecs,” Domingo Betanzos, the first bishop of San Germán de Guatemala, and the Portuguese missionaries Francisco Álvares and Simão Rodrigues, who preached in Sub-Saharan Africa and the East Indies, respectively. Las Casas himself would be named the bishop of Michoacán and auxiliary bishop of the Ilhas Miguelinhas [6], while Sahagún would end his days as the bishop of México-Tenochtitlan.

______________________________________

[1] Two years earlier than IOTL

[2] IOTL the university system in Portugal had no set, central location until the 1530s when João cemented it at Coimbra - here it's been split into two colleges at Brava and Coimbra

[3] What would have been TTL's Requirimiento

[4] Miguel was at Cartagena at the time

[5] St Francis Xavier

[6] OTL's Philippines

Last edited: