«En profunda angustia y ansiedad mental, estoy obligado a familiarizarme con su excelencia con la derrota total de las tropas bajo mi mando».

«In deep anguish and mental anxiety, I am compelled to acquaint Your Excellency with the complete defeat of the troops under my command.».

— Attributed to Major-General Horatio Gates.

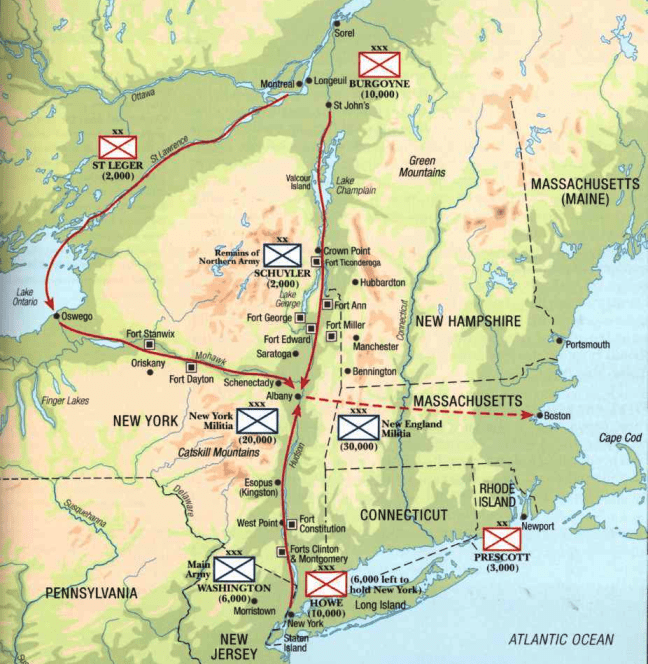

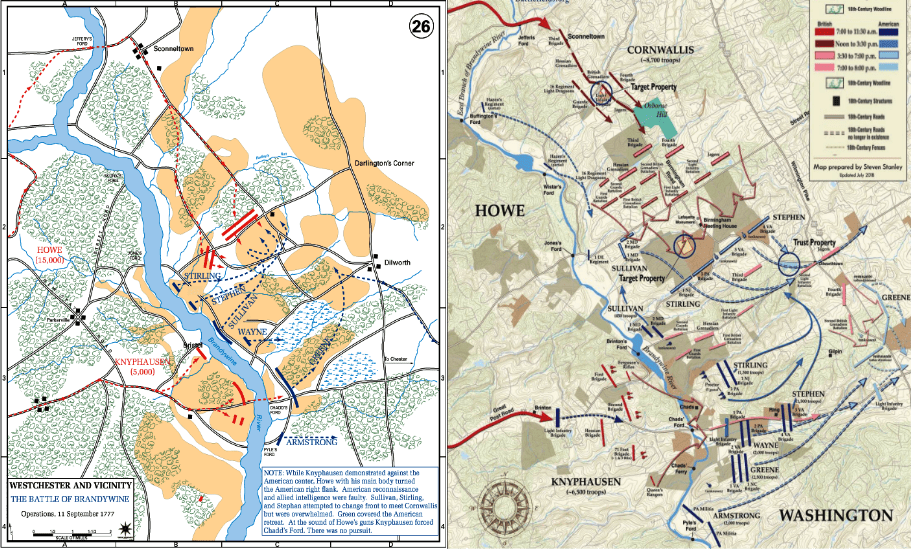

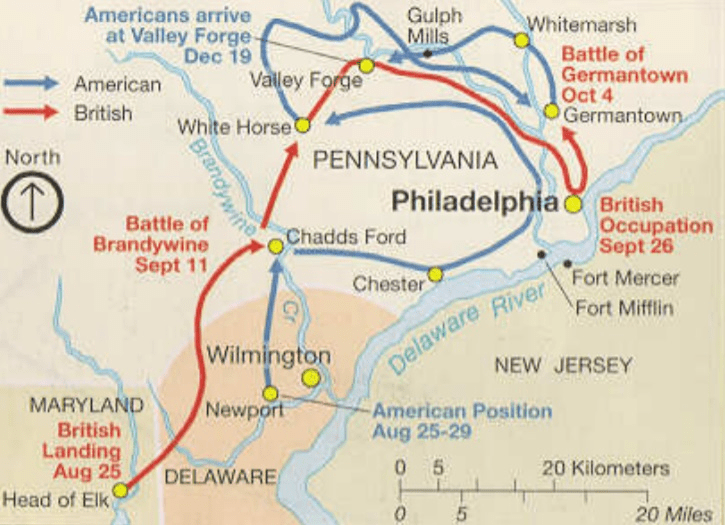

Stalemate in the northern theater of the war after 1778-79 prompted British leaders to renew their interest in the southern theater. The British, most importantly, their commander Henry Clinton remained convinced that the southern colonies were full of Loyalists waiting for the British authorities to free them from Patriot rule. Clinton also realized that he could not take the north with the forces he had been given. Patriot forces had repelled attempts to establish themselves in the southern colonies at Moore Creek Bridge and Charleston in 1776, but the successful capture of Savannah, Georgia, in late 1778; it had restored British hopes that Charleston might be captured and that this success would contribute to increased loyalist support for the British campaign to quell the rebellion. The reality was that South Carolina was a deeply divided state, and the British presence unleashed the full violence of a quasi-civil war on the population. First, the British used Loyalists to pacify the Patriot population; the patriots returned violence in kind. Guerrilla warfare strategies employed by patriots Francis Marion, Thomas Sumter, and Nathanael Greene throughout the Carolina campaign of 1780-81 eventually hunted down the much larger British force in Virginia. Meanwhile, the Americans knew that Charleston was a likely target for the British following the capture of Savannah. Major General Benjamin Lincoln had been given command of the defense of Charleston in September 1779. In his initial instructions to Lincoln, General George Washington warned him of the impending British attack, but lamented that he was unable to offer military assistance due to the need. to maintain adequate continental forces around Britain's northern stronghold in New York City.

By the time Lincoln arrived, many of the forts defending Charleston Harbor were in poor condition, and the fortifications on its west and south sides (the sides facing the city's land approaches) were unfinished. Lieutenant General Henry Clinton's expeditionary force of some 8,500 British and German soldiers, and 6,000 sailors; he left New York just after Christmas in 1779. He left the important New York City garrison under the command of Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen. The British Regiments were: 1st Light Battalion drawn from the Regiments, 2 Grenadier Battalions drawn from the 7th, 23rd Royal Welch, 33rd, 42nd, 63rd, and 64th, and the Queen's Rangers. The army was transported by a fleet of 90 transports escorted by 14 Royal Navy ships, with 5 ships of the line and 9 frigates. December through January was a dangerous time for the weather and the fleet was caught in strong winds at Cape Hatteras, which could turn into a typhoon. Most of the army's horses died in the storms and those that survived had to be put down and the ships scattered. A ship carrying Hessian troops was brought across the Atlantic and landed on the Cornish coast in south-west England. A ship with heavy guns was sunk, and several more were taken by American privateers. Clinton, who had always been a poor sailor, hated the sea and spent most of the voyage seasick. As January drew to a close, the British fleet arrived at the mouth of the Savannah River and landed on Tybee Island on February 1 to assemble the rest of the fleet. After 10 days, Clinton declared that the army was ready to proceed and on February 11, troops began landing on Simmons Island and for the next 10 days the men scoured swamps on James and Johns Islands.

Clinton settled the men in a difficult camp and halted their advance, apart from establishing a beachhead at the Stono ferry on the mainland. Clinton wanted to prepare the force for him. He needed to establish supply depots and magazines, and he also sent reinforcements from detachments in Georgia and ordered more troops to be sent from New York. Clinton also had to wait for the navy to reach the upper harbor of Charleston, where his heavy guns could be brought ashore for the siege and the boats could be used to ferry troops across the Ashley River to the peninsula Charleston was on. . The entrance to Charleston Harbor was defended on the north side by Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island and on the south side by Fort Johnson on James Island. In 1776, the 2nd South Carolina Continental and a force of artillerymen repulsed an attack on Sullivan's Island by Commodore Peter Parker's British Royal Navy squadron. Since that time the forts on either side of the estuary had fallen into disrepair and were ungarrisoned, but were reoccupied on learning of the British arrival. The city of Charleston sits on an isthmus, connected to the mainland by a tongue or neck of land. Charleston is bounded on the west by the Ashley River and on the east by the Cooper River. The two rivers meet in the estuary at the southern end of Charleston. Inadequate defenses had been built into the language. Charleston was the only city in the southern states to normally have some 12,000 citizens, most of them of English origin, but with a mixture of black slaves, French Protestants, and a sprinkling of Germans. Nature offered a more formidable defense in the form of a heavy sand bar. The bar could be crossed in five places, but all the crossing points were so shallow that heavy ships could not pass. Frigates and smaller vessels could do it, but not without first lightening their load.

A series of log terraces protected the end of the tongue, and along each river were redoubts, trenches, and small fortifications. The redoubt at the point had 16 heavy guns, and the forts along the river had 3 to 9 guns each. However, Benjamin Lincoln, commanding the city's garrison, expected an attack by sea and neglected the land defenses and even the completion of the earthworks that stretched across the neck. At the heart of the land defenses was the citadel, or hornwork or "old royal work", which was a fort made of "tapia" or "tappy", which was a mixture of oyster shells, lime, sand and water. The fort had 18 cannons. There were redoubts on both sides, but they weren't complete, they weren't even well placed. During the month that Clinton took to advance, the Americans, under the direction of Governor Routledge, worked frantically to build the city's defenses, using a labor force of 600 slaves recruited from neighboring plantations. The Americans dug a flooded ditch in the neck, backed by double avatis and strong defensive work, supported by redoubts. The main redoubt was a stone hornabeque, located in the center of the line where the road passed through the neck, and was called Citadel. 66 guns were placed along the line. At the southern end of Charleston, facing the sea, a redoubt with 16 guns was built. Along the bank of the Ashley River, 6 small redoubts were built, each with 4 to 9 guns. Along the Cooper River, 7 redoubts were built, each with 3 to 7 guns. On the estuary, Forts Johnson and Moultrie were repaired and armed. A fleet of American ships defended the port of Charleston, commanded by Commodore Whipple with the ships Bricole (44), Providence (32), Boston (32), Queen of France (28), Aventure (26), Truite (26) , Ranger (20), General Lincoln (20) and Notre Dame (16).

Several of these ships had been purchased from Admiral Estaing before the French withdrew from Savannah. When Clinton landed, Lincoln had under his command 800 South Carolina Continentals (1st, 2nd, and 5th), 400 Virginia Continentals, some 380 Polaskis Legion, 2,000 Carolina militia, and a small number of Horry's dragoons. In April, before Clinton shut down the city, he would be reinforced from Virginia and North Carolina. Governor Routledge summoned the South Carolina militia to garrison Charleston, but they were unable to comply with the summons, claiming that there was a danger of smallpox in Charleston. He also wrote to the Spanish authorities in Havana, requesting the assistance of a Spanish fleet and army. The Spaniards excused themselves from helping, seeing it necessary to secure their most important possessions. General Clinton left 2,500 troops in Savannah and arrived in Charleston with 6,000. He then sent transports back to New York to bring in additional troops, and called the Savannah garrison to join him. As part of his US Army readiness, General Lincoln sent General Isaac Huger with US mounted troops, some 500 men from various regiments, to Monk Corner, 30 miles upriver from Charleston on the Cooper River, to keep open the Charleston route north. Huger's detachment left Lincoln with around 2,650 Continental troops and 2,500 militiamen, with a circuit of some 5 km of fortifications to defend. Towards the end of March, British warships began to move up the estuary towards Charleston. The American squadron moved to the mouth of the Cooper River and several warships and civilian vessels sank through the river's entrance, joining together to form a barrier from Charleston to Shute Folly Island. The rest of the American squadron stood upriver from the boom.

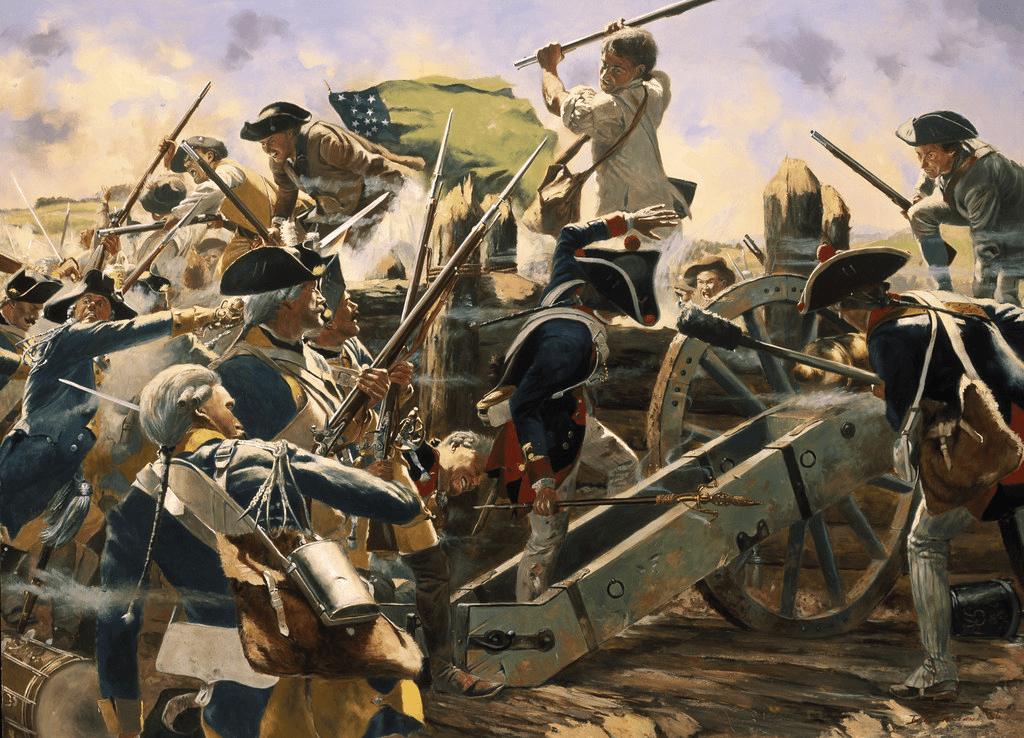

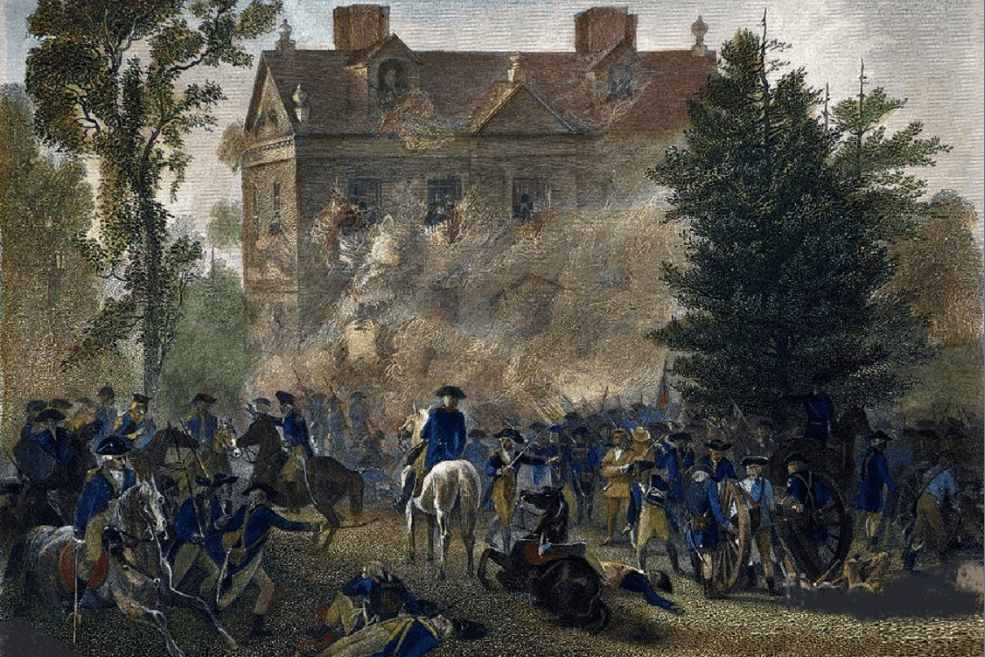

The cannons were removed from American warships to increase ground defenses. Meanwhile, Clinton had gathered troops and supplies from him, and even obtained 1,500 more men from Georgia. He was ready for the siege. On the night of March 29, Clinton began sending his reinforced army across the Ashley River at Draytons Landing, 12 miles from Charleston. The Americans did not oppose the landing, and by April 1, Clinton's forces had advanced less than 1,000 meters from the defenses through the neck. There, they began a process of opening the first parallel, where British engineers, some 800 meters from the American lines, built approach trenches and redoubts that were more or less parallel to the American defensive works. On April 8, the British ships sailed up past Fort Moutrie and anchored in the estuary between James Island and Charleston. Cannons were carried for the British batteries that were established at the neck. On April 10, the British batteries on the neck were ready to open fire on the Charleston. General Clinton asked General Lincoln to surrender, which he refused to do. On April 13, British guns opened fire from batteries on the neck and from James Island, using red-hot bullets. The shooting continued until midnight, setting parts of the city ablaze. The distance of only 800 meters would make artillery fire extremely effective by the standards of the time. In general, most guns were unreliable beyond 1,200 meters, with 400-800 being the effective range. The next day, General Lincoln called a council of his superior officers. Lincoln stated that he considered the situation desperate and he was considering leaving town. General Lachlan McIntosh urged the troops to leave Charleston and be transported to the east side of the Cooper River, but Lincoln refused to make a final decision on whether to leave.

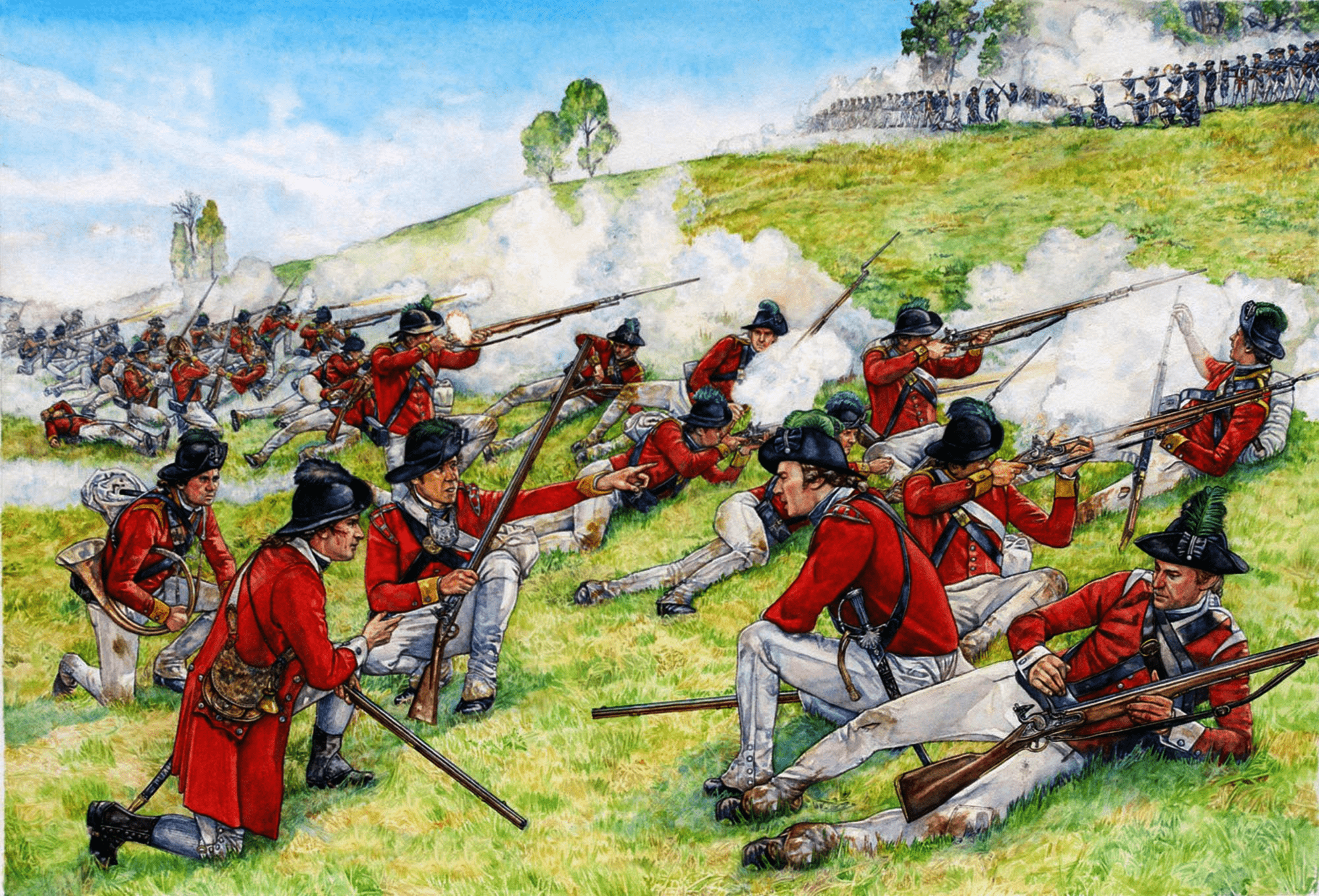

In mid-April 1780, the British officer, Lord Rawdon, arrived from New York with 2,500 other men. In addition, there were 5,000 British sailors available from the fleet. Meanwhile, the British cavalry, commanded by Colonel Banastre Tarleton, was moving against the Americans at Monk Corner. The British horses had been lost in the storms at Cape Hatteras, but Tarleton replaced his mounts with local horses. On April 14, Tarleton surprised the American cavalry in the camp at Monk Corner with a surprise attack at 03:00. The American force was destroyed, and those who did not become casualties scattered. Tarleton captured enough horses for his dragoons, along with wagons and supplies. Lieutenant Colonel Webster with the 33rd and 64th joined Tarleton, and headed south along the eastern bank of the Cooper River about 10 km from Charleston, cutting off America's escape route across the river. By April 19, the British approach trenches had advanced to within 250 meters of the American line at the neck, and began digging the third parallel. The exchange of artillery between the two forces poses an interesting situation. British engineers are getting closer to the Americans. The Americans are firing at them and the British lines, the British are shooting over the heads at the Americans, but the artillery at the time was inaccurate and the rounds commonly fell short. So it was difficult for the engineers to know who was shooting at them. As they got closer, they could see firsthand the effects of their artillery. One shell hit an American emplacement, reported by a British engineer: "It burst on fall, throwing two emplacement gunners into the trench and exploding the enemy platform."

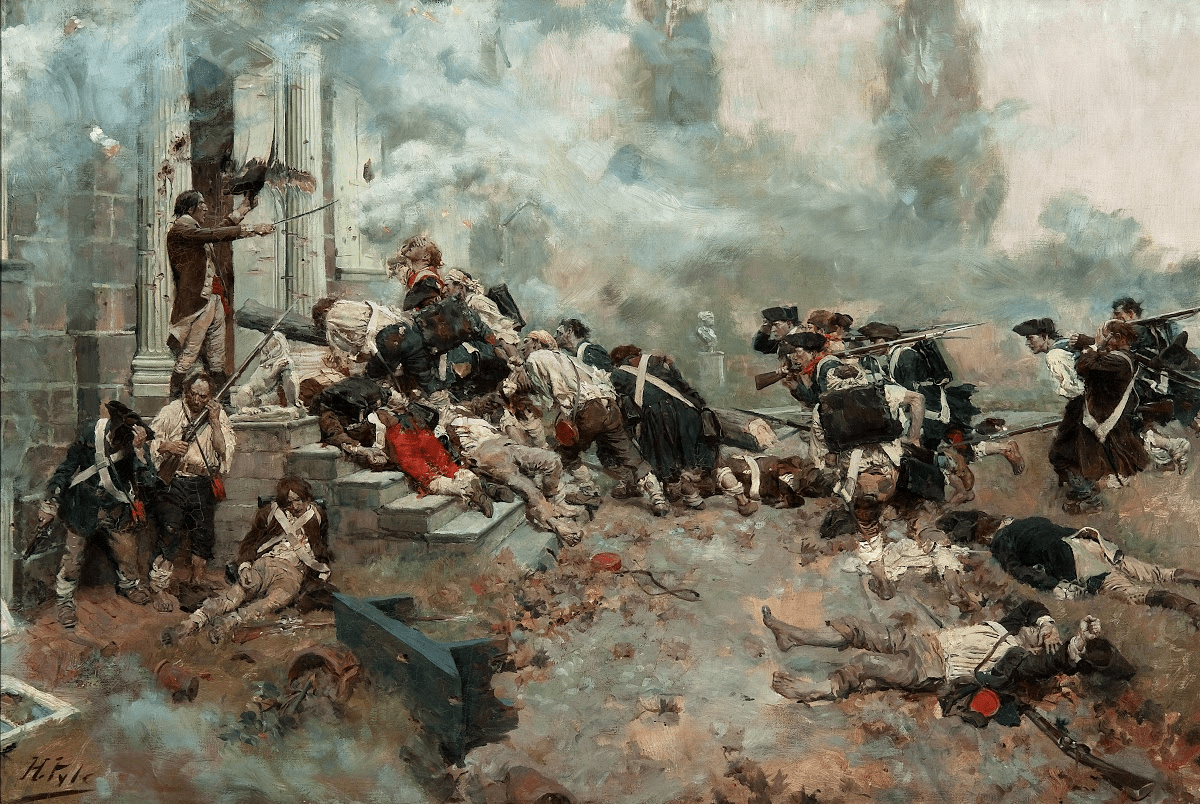

By the end of April, the third parallel had been completed. The men were almost on top of each other. Clinton had insisted that his men stationed in those trenches NOT load muskets, but use the bayonet. For Clinton, the bayonet meant discipline, pride, and spirit. It was probably a multitude of factors, unloaded muskets and horror or artillery included, that caused his men to panic on the third parallel on the night of April 24, when 200 Americans made a sortie against one end of the third parallel. The jägers fled towards the second; but the Americans still managed to kill about 50 and capture at least a dozen more. The following night on April 25, the men stationed on the third parallel abandoned their post when they heard small arms fire and screams from the US side; which in turn provoked a savage round of fire from the men on the second parallel, thinking that their comrades had been overrun and that a force of Americans was right behind them. An officer whose men had fled from the third parallel later said: 'Everywhere they saw rebels. They believed that the enemy had made a raid and fired musketry for more than half an hour, although no rebels had passed the ditch." Lincoln called another council of war, which was attended by Lieutenant Governor Gadsden. Lincoln proposed the alternatives of abandoning the city and withdrawing or capitulating on terms. Gadsden strongly opposed either proposal, threatening that the townspeople would turn on the American troops. Lincoln relented in council, but took matters into his own hands by proposing terms for a capitulation to the British. The terms, which allowed US troops to leave Charleston, were rejected by Clinton. Further fighting took place the following night, with an American incursion into the British siege lines, the British capturing a redoubt at Haddrell Point and Colonel Arbuthnot taking Fort Moultrie, whose garrison surrendered without a fight, in contrast to the defense put forward. by his predecessors on June 28, 1776.

On May 8, 1780, the British trenches were close to the American line at the neck and the flooded ditch leading to the American position was drained. Before an all-out assault, the British again summoned the American garrison to surrender. This time there was no alternative. The Americans could no longer escape from Charleston. British troops had occupied the east bank of the Cooper River, the Neck, and the opposite bank of the Ashley River. Ships of the British Royal Navy held the estuary. Lincoln asked for an extension to consult his officers on the question of surrender, and gave him until May 9. Lincoln demanded terms by which the American military would be released and American continental troops would be allowed to surrender with the honors of war. The British rejected this proposal. The next night was spent by each side bombarding the other with all the artillery at their disposal. This time, firing at wooden houses, the British artillery proved more effective, and many houses were set on fire, the civilian population decided that they had enough, and they asked Lincoln to surrender. Lincoln agreed to Cornwallis's terms. The American military would lay down their weapons and be allowed to return home with the promise of no further involvement in the war. American continental troops would become prisoners of war. On May 12, 1780, American continental troops marched out, their drums beating a Turkish march, officers allowed to keep their swords until cries of "Long live Congress!" unnerved the British, so that their swords were taken from them and they became prisoners. The militia surrendered their firearms and were eventually allowed to return to their homes, pledging never to fight the British Crown again.

During the fighting the British lost 76 men killed and 189 wounded. American losses during the fighting were 89 Continentals killed and 138 wounded. Very few US militias became victims. In the surrender, 5,466 American soldiers became prisoners. The British took 5,916 muskets, 391 cannon, 15 regimental colours, 33,000 cartridges and 8,000 cannon shots. They also captured the Charleston powder magazine which contained some 10,000 pounds of gunpowder, in addition to large stores of rum, rice, and indigo. Three days after the surrender, a tragic accident occurred. The captured muskets had been carelessly thrown into a wooden building where the powder was stored. A loaded musket must have been fired on the pile. The explosion that followed set six houses on fire and killed around 200 people. It was feared that the main magazine, with its considerable powder store, would catch fire and explode, but that did not happen, and the fire was put out by soldiers on both sides, residents of Charleston, and the group of slaves recruited in Charleston from neighboring plantations. by the Americans to build the defenses. After the capture of Charleston, the British advanced through the rest of the colony of South Carolina in what became a fierce civil war. On May 12, 1780, Charleston fell to the British under the command of Henry Clinton. A column of reinforcements consisting of 380 troops under the command of Colonel Abraham Buford failed to reach the town before its fall and turned to retreat north. This force, known as the 3rd Virginia Detachment, consisted of 2 Virginia RI-2 Corps, 40 Virginia Light Dragoons, and 2×6 guns. As Buford's detachment traveled north, they encountered several prominent citizens of South Carolina fleeing the advancing British. Even Governor John Rutledge joined the column as it moved toward the North Carolina border.

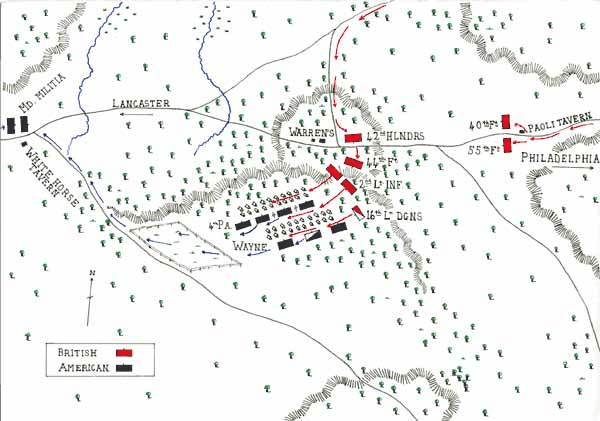

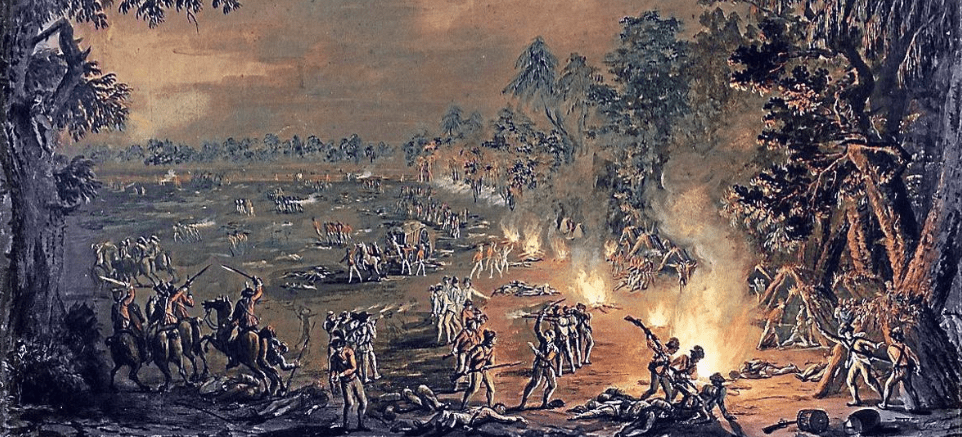

General Clinton returned to New York, leaving General Charles Lord Cornwallis in command of the Army of the South. Cornwallis learned of Buford's column and sent a force under Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton to trap and destroy the Continentals. Tarleton commanded 270 men from his British Legion, 170 were dragoons and 100 were mounted infantry, 40 light dragoons from the 17th and a 3-pounder. Although the Americans were a week ahead of Tarleton, the aggressive British commander moved his men 150 miles at a brisk pace, reaching Buford on the afternoon of May 29, 1780. The area where the two forces met found is situated along the border of North and South Carolina, in an area called Waxhaws, in the Catawba River Valley. Tarleton sent a message to Buford, demanding that the Americans surrender, but they refused. Buford then ordered all of his heavy baggage and cannon to continue moving north, so his artillery would be in the battle. He then formed a line to meet the advancing British and Loyalists. His position was in an open wood to the right of the march route, with all his infantry in a single line. The American colors were placed in the center of that line. Buford ordered his men to hold fire until the British were within 10 meters. Seeing the rebel line spread out for battle, Tarleton divided his force into three attack columns. He deployed 60 British Legion dragoons, as well as another 60 mounted infantry from the right column, intending that the mounted infantry dismount and fire on the Americans, pinning them down. At the same time, he formed a central column of his elite troops, the 40 light dragoons of the 17th, as well as 40 mounted infantrymen of the Legion, to charge directly into the American center under covering fire from the Loyalists at the helm. right of him.

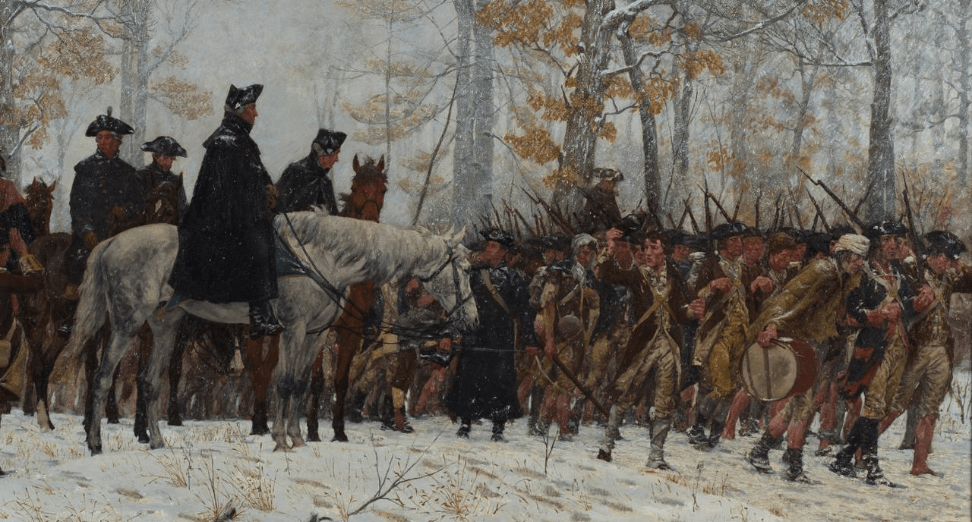

The left column was led by Tarleton himself and consisted of 30 carefully selected Legion men, with as many infantrymen ready to sweep the American right flank and to attack for their baggage and reserves. Tarleton held his single cannon in reserve with the remaining Legion mounted infantrymen. The British attack began as soon as all of his troops were in position. Colonel Buford gave the order to refrain from firing until the British were within 10 meters, the American forces were overwhelmed by the speed and aggressiveness of the British charge, Buford's men had time to fire a single volley before the British horsemen reached the line. The thin American line broke and they began shooting down soldiers left and right. Many American survivors of the battle claimed that their comrades were massacred while trying to surrender. As quickly as it had started, the Battle of Waxhaws was over. British casualties were light, with 5 killed and 14 wounded. The Americans lost 113 men killed and 203 wounded, 2 guns and 26 wagons were captured. Colonel Buford managed to escape the massacre. The Battle of Waxhaws became known as the "Buford Massacre" and Tarleton, already known as an aggressive commander, was condemned as a butcher. Clinton returned to New York on June 5, 1780, after the southern remnants of the Continental Army had been defeated in May 1780 at the Battle of Waxhaws, charging Lord Cornwallis with the pacification of the remaining parts of the state. The remaining Patriot resistance in South Carolina consisted of the militia under commanders such as Thomas Sumter, William Davie, and Francis Marion. Washington sent RIs from the Continental Army south, consisting of the 1st and 2nd Brigades from Maryland and the 1st Brigade from Delaware, under the temporary command of Major General Jean, Baron de Kalb. They had left New Jersey on April 16, 1780, arriving at the Buffalo ford on the Deep River, 30 miles south of Greensboro, in July.

On July 25, Major General Horatio Gates, the hero of Saratoga, arrived at General Johann Baron de Kalb's Patriot camp on the Deep River in North Carolina. Gates decided to advance to the nearest British outpost at Camden, which had a 1,000-man garrison, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Francis Rawdon. On July 27, the Patriots headed for Camden. Gates had chosen a direct march to Camden through the swampy and difficult terrain against the advice of his officers, who were familiar with the area. They had recommended a route that would have started west and then south. It was more roundabout, but through regions friendly to the Patriots, which meant they could collect some desperately needed food and supplies. The route Gates chose was more difficult, barren in nature, abundant in sandy plains, intersected by swamps, and very sparsely inhabited, and the few inhabitants they may encounter were likely hostile. All the troops had been short of food since their arrival at the Deep River. Gates also weakened his force by sending 400 Continentals to assist Colonel Thomas Sumter, who had requested reinforcements to carry out his own raids. Gates' original strategy was to use Major General Francis Marion and Sumter to cut off Camden's supply lines from the south. This action would leave Camden vulnerable and force the British to evacuate the garrison from it without a fight. On August 3, Gates joined 1,200 North Carolina militiamen under the command of General Richard Caswell. On August 7, at Rugeley Mill, 15 miles (24 km) north of Camden, 700 Virginia militiamen under the command of General Edward Stevens joined Gates's army. Also, Gates had Armand's Legion. However, by this stage, Gates no longer had the help of Marion's or Sumter's men, and had in fact sent 400 of his Continentals to assist Sumter with a planned attack on a British supply convoy.

Gates also refused the help of Colonel William Washington's cavalry. Gates apparently planned to build defensive works some 9 km north of Camden in an effort to force the British abandonment of that important city. Gates told his aide Thomas Pinckney he had no intention of attacking the British with an army made up mainly of militiamen. Camden was garrisoned by about 1,000 men under Lord Rawdon. General Cornwallis, alerted to Gates's movement, on August 9, marched from Charleston with reinforcements; arriving at Camden on 13 August, increasing the effective strength of the British troops to 2,239 men, of whom 1,000 were regulars: 23rd Royal Scots (292), 33rd (238), Fraser's 71st Highlanders (1st Battalion 144 and 2nd Battalion 110), light companies (148); Protestant Irish Volunteers (303), Tarleton's Legion (126 Infantry and 182 Light Dragoons), North Carolina Regiment (267) Provincial and Loyalist Militia (202), and Artillery. Gates ordered a night march to begin at 10 p.m. on August 15, despite his army of 3,052, two-thirds of whom were militiamen, who had never maneuvered together. Unfortunately, his dinner acted as a purgative as they marched, with Armand's cavalry in the lead. In the opposite direction marched Cornwallis's army, also on a night march at 10 p.m., with Tarleton's dragoons in the lead. A brief period of confusion ensued when both forces collided around 02:00, but both sides soon parted ways, not wanting a night battle. The forces formed for battle before first light. Horatio Gates deployed his 4,100 troops in a line and reserve.

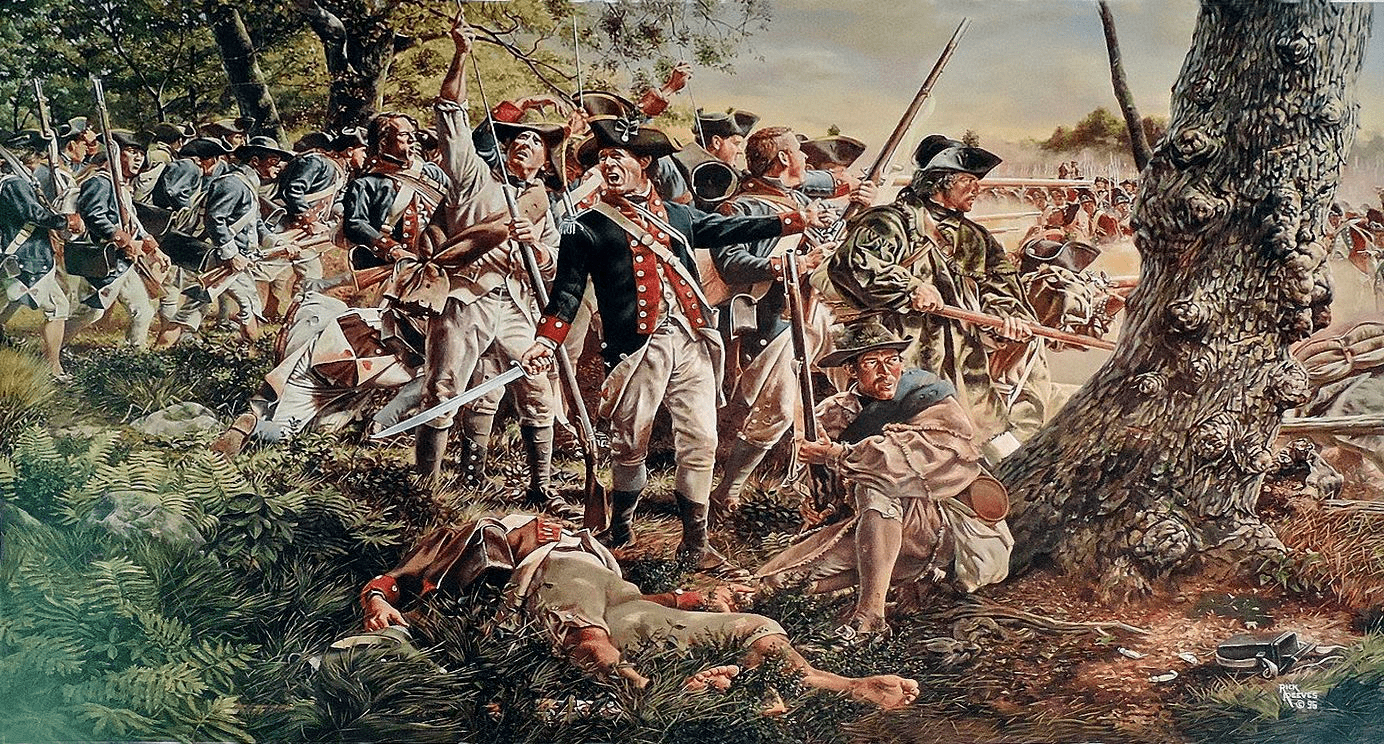

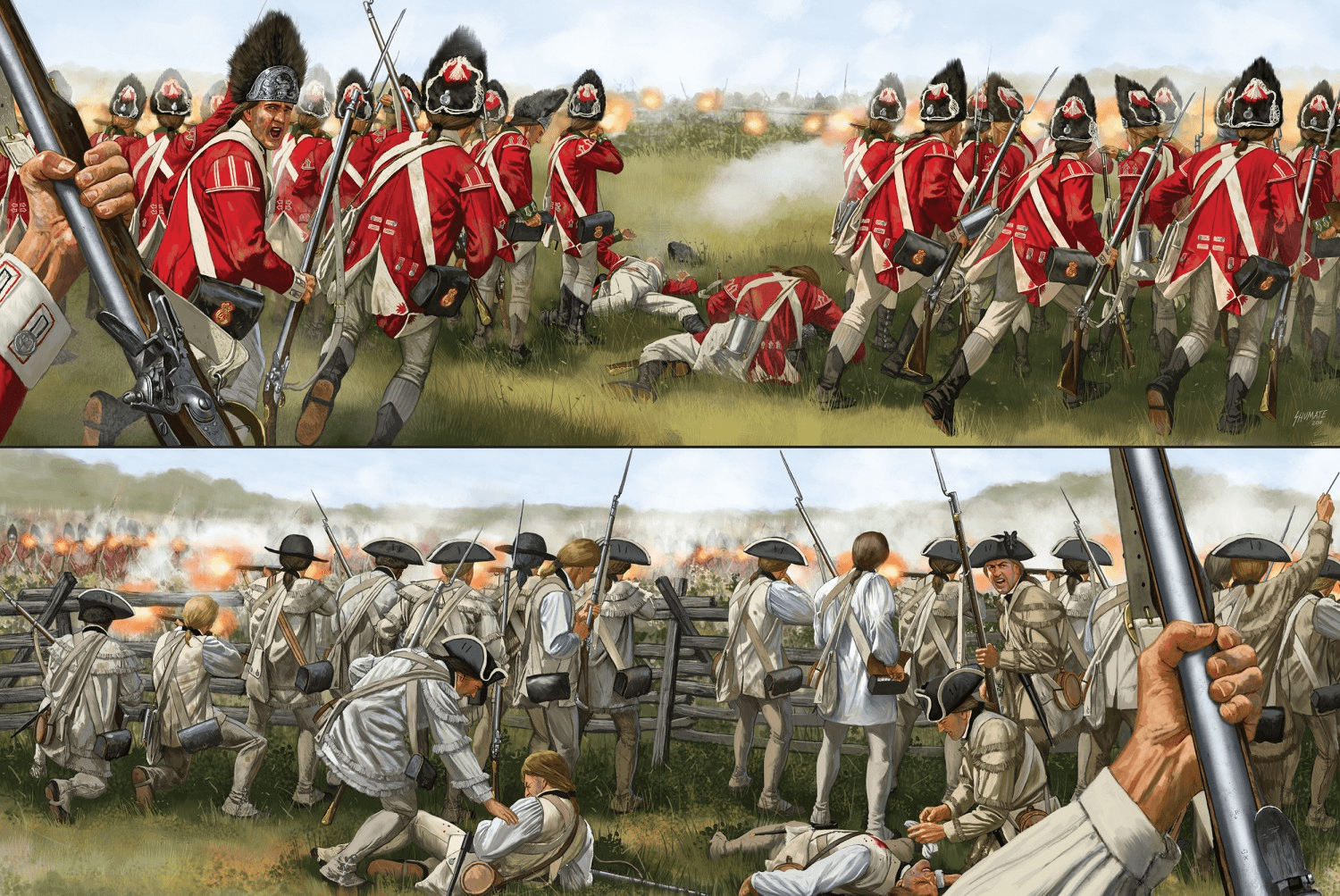

Gates' formation, although typical British practice of the time, pitted his weaker troops against the more experienced British regiments. Cornwallis had approximately 2,239 men, and he deployed in a line and reserve in front of Saunders Creek. He placed his most experienced units on the right flank and his less experienced units on the left flank. When Gates discovered that he was facing Cornwallis and an experienced British force, he decided it was too late to withdraw and prepared for combat. The battlefield stretched in a narrow front across the swamps along Gum Creek. Gates's deployment had placed the least reliable troops against the best British regulars. The British opened the battle by using their right wing to attack the Patriot left. Facing an aggressive British bayonet charge, the militia fled before the British could even reach them. The Virginians broke and ran. Only one company of the militia managed to fire a few shots before fleeing. The panic quickly spread to the North Carolina militia and they too fled, running through the Maryland mainlanders. Seeing the utter panic of his entire left wing, Gates mounted his horse and hit the road with his militia, leaving the battle under the control of his subordinate officers. In just a matter of minutes, the entire left wing of the Patriot force was gone. As the rout unfolded on the left flank, Kalb's right flank attacked after being ordered by Gates. The mainlanders twice repulsed Rawdon's troops and then launched a counter-attack. The mainland counter-attack was successful and Rawdon's line was all but broken. Cornwallis saw the action and was forced to get into the action and stabilize his men. Meanwhile, instead of pursuing the fleeing militia, Webster turned to the left and continued to charge him as a flanking move against Kalb.

The North Carolina Militia Regiment that had been stationed closest to the Delware Continentals stood their ground, being the only Militia Regiment to do so. They fought well and were joined by Maryland Continentals who had been called up from the reservation by Kalb. The Marylanders fought off Webster's attack, but then only about 800 Continentals were facing at least 2,000 British regulars. The final blow came when Cornwallis ordered Tarleton to attack the Patriot rearguard. Under the cavalry charge, the patriots finally broke. Some managed to escape through the swamp and Kalb was wounded 11 times (8 by bayonet and 3 by musket balls) before he fell. The field was taken after an hour of fighting. Tarleton pursued the fleeing Patriots for over 20 miles before finally turning back. Gates, mounted on a fast horse, was almost 100 km away in Charlotte, North Carolina, that same night. About 60 mainlanders joined as a rear guard and managed to protect the troops in a retreat through the surrounding forests and swamps. British casualties were 68 killed, 245 wounded and 11 missing. The Patriots had 240 known dead, of which 162 were Continentals, 12 South Carolina militiamen, 3 Virginia militiamen, and 63 North Carolina militiamen. 1,500 prisoners were taken, of whom 290 were wounded and were taken to Camden after this action. Of this number, 206 were Continentals, 82 were North Carolina militia, and 2 were Virginia militia. The British captured 8 guns and about 200 wagons. Gates continued on to Hillsborough, a distance of some 300 km, where he arrived on the 19th and then wrote his report to Congress on August 20. The report to the president of the Continental congress, Samuel Huntington, began: "In deep anguish and anxiety of mind, I am bound to acquaint myself with his excellency with the total defeat of the troops under my command."

In an August 30 letter to General George Washington, Gates wrote: “But if being unlucky is reason enough to remove me from command, I will gladly submit to the bidding of Congress; and I will resign a position few generals would be eager to hold…” Gates's actions were called into question almost immediately. After Major General Nathanael Greene replaced him in December, Gates returned to his home in Virginia to await an investigation into his conduct during the battle. A congressional investigation in 1782 cleared him of wrongdoing, accepting his claim that his reason for leaving was to get to a place of safety so he could rebuild his army. He would not have another command for the rest of the war, but he did return to active duty before the war's end, serving on the Washington staff. Greene succeeded Gates as the new commander of the continental forces in the south. This loss left American morale in the South at a low level and the region firmly under British control until Geene built up Continental forces in early 1781. Kalb died 3 days after the battle. Despite the defeat, the patriot militias began a guerrilla war against the British, an example is the attack on British forces of the 63rd who were escorting prisoners to Charleston, Marion's guerrillas attacked to free them on August 20. Believing that British and loyalist forces were in control of Georgia and South Carolina, he decided to head north and address the threat posed by the remnants of the Continental Army in North Carolina. In mid-September he began moving north toward Charlotte, North Carolina. Cornwallis's movements were shadowed by North and South Carolina militia companies. One force under Thomas Sumter stayed behind and harassed British and Loyalist outposts in the South Carolina countryside, while another, led by 24-year-old Colonel William Richardson Davie, kept in fairly close contact with parts of his force. as Cornwallis moved north.

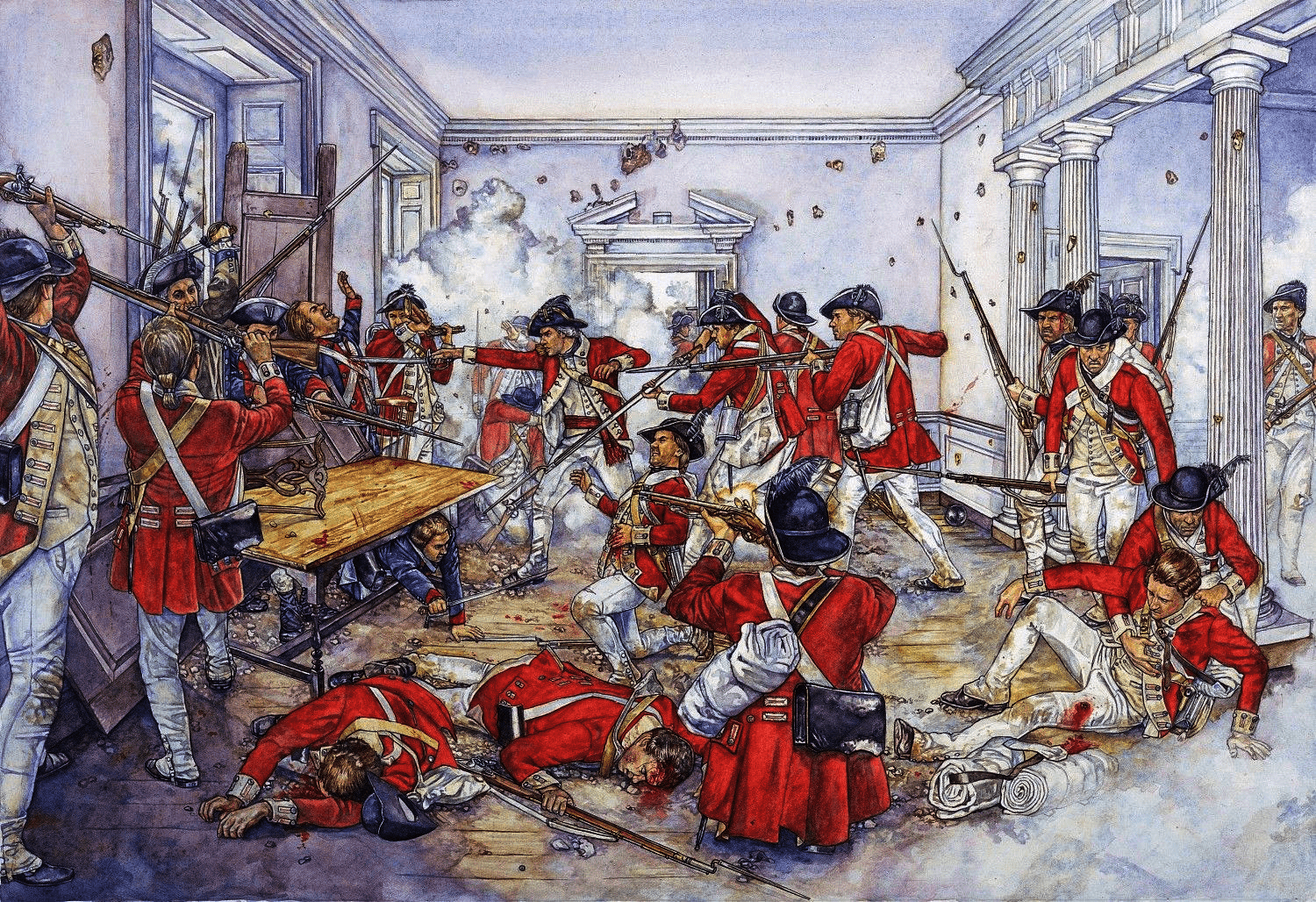

Davie had done a good job in the three months after the fall of Charleston. He had several times defeated small units of the British Army and captured supply trains, but they were no match for the entire British Army. His orders were to keep an eye on the British, report their movements to General William Lee Davidson, who commanded the Mecklenburg and Rowan militia, and attack any targets of opportunity they could find. Davie successfully surprised a detachment of Cornwallis's loyalist forces at the Wahab plantation on September 20, and then moved on to Charlotte, where he staged an ambush to harass Cornwallis's vanguard. Charlotte was then a small town, with two major highways intersecting in the center of town, where the Mecklenburg County Courthouse dominated the intersection. The south façade of the courthouse had a series of pillars, between which a stone wall approximately 1 meter high had been built to provide an area to serve as a local market. He was joined by a group of Mecklenburg militia commanded by Major Joseph Graham and they took up their positions around the courthouse. Davie posted three ranks of militiamen in and to the north of the courthouse, with one behind the stone wall, and posted companies of cavalry on the east and west sides of the courthouse, covering the roads leading in those directions. Finally, he put a company of 20 men behind a house on the south road, where he awaited the British advance. As his British column approached Charlotte, Cornwallis sent Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton's British Legion ahead, Tarleton was recovering from a violent fever, so Major George Hanger with the light dragoons was sent ahead to investigate. .

Cornwallis ordered Hanger to cautiously enter the town and check for militia, which he expected to be in the area. As the Legion moved slowly down Tryon Street towards the square, they saw that the street was empty. Contrary to Cornwallis's orders, Hanger and his cavalry merrily advanced toward the center of the city. Even after the 20 men behind the house opened fire, Hanger's men continued to ride until he was met by heavy fire from the militia line behind the stone wall. As the first line of militia maneuvered to make way for the second, Hanger mistook his move for a retreat and continued the charge. This brought him into a withering crossfire from the second line and the cavalry companies stationed to the east and west. Hanger went down with a wound, and his cavalry retreated in disarray back to the Legion infantry behind him. The British cautiously followed them for a few miles and discovered the American camp at Charlotte. Hanger sent his light infantry, commanded by Lt. Col. James Webster, to clear militiamen from his positions along the fences in the road. Webster's counter attack forced the Patriots to abandon the fences along the road and fall back to the stone wall. Hanger personally led his cavalry against the 20 mainland dragoons. Davie's troops drove the British back in the first assault. Hanger then led a second cavalry charge against the stone wall and was again stopped and forced back. Cornwallis, alerted by the sound of battle, stepped forward to assess the situation. Sarcastically yelling “you have everything to lose, but nothing to gain”, he ordered the Legion forward once more. By this time light infantry from the main army had also begun to arrive, and Davie withdrew his forces.

Hanger called the incident "an insignificant skirmish," but made it clear to Cornwallis that he would have to expect more resistance. Major Joseph Graham was wounded by three bullets and six sword cuts and was presumed dead. He survived his injuries and lived to become a prominent citizen of Charlotte. Hanger was also wounded, further disabling the effectiveness of Tarleton's Legion. Instead of advancing through Hillsboro, Cornwallis occupied Charlotte. The British Army remained in Charlotte for two weeks collecting food and supplies, but they had gained a new respect for the Americans and would later refer to Mecklenburg as "The Hornet's Nest of the Rebellion". General Cornwallis was having trouble subduing the Carolinas. Every time he thought he was making progress, his supply wagons were captured or small portions of his army were defeated by the guerrilla fighting of the patriot militia. The defeat of the Patriot army at Camden had been devastating and demoralizing, but the Patriots did not admit that they had been defeated. Cornwallis decided to divide his superior army into three branches, hoping to subdue the patriots in the Carolinas once and for all. Banastre Tarleton with the British Legion took the eastern branch and was brilliant and brutal. Major Patrick Ferguson was given a small group of 200 redcoat-wearing New York provincials and told to recruit loyalist militia to the cause in the Western Branch. Ferguson recruited brilliantly and soon had almost 4,000 loyalist militiamen. Ferguson patiently trained them and by September 1780, he had some 1,000 militiamen marching with him. The problem with the militia was that they always came home, and Ferguson rarely had more than 1/4 of the militia with him. They came in and out of the army as they pleased, and Ferguson couldn't control them. In an effort to discourage attacks in that western part of the Carolinas, Ferguson sent a message to the leaders of the Overmountains who lived west of the Appalachian Mountains. These men had been left out of the war zone. So Ferguson hoped to discourage them further. The message said, in part, that if the mountain men took up arms against the King, Ferguson would "march his army over the mountains, hang his leaders, and lay waste their country with fire and sword."

It was the wrong message to send to a group of stubborn Scots-Irish who were only interested in defending their homes on the border. Overmountain leaders Isaac Shelby and John Sevier took this threat seriously. They sent word across the mountains that they were heading east to fight Patrick Ferguson. Ferguson had turned an impersonal war into a personal challenge by threatening the houses of the mountain men. To facilitate the British offensive against the Patriots, Cornwallis assigned Major Patrick Ferguson at the head of the British Legion to eliminate the Patriots in the Carolinas and to protect the left flank of Cornwallis's army in Charlotte, North Carolina. Ferguson began leading his troops, made up entirely of American loyalists, searching for rebel militias. Time and time again, he missed confrontations with groups of backwoods supporters. The men of the mountain (Overmountain) met at Sycamore Shoals on September 25. Nearly 1,000 of them gathered, and after a fiery speech, they set out to find Patrick Ferguson. They traveled through the mountains on their horses through an early autumn snow. It was a difficult journey, but these men were used to hardship. They had defeated the Cherokees, could Patrick Ferguson and his army be any more difficult? They carried their long hunting rifles: although slow to load, these rifles were highly accurate even at long ranges. Along the way, the mountain men were joined by militia groups and others who decided to fight on the spur of the moment. On September 30, the Highlanders reached Burke County, North Carolina, where they met with 350 other North Carolina militiamen. Totaling 1,400 militiamen, the force was led by five different leaders, each holding the title of colonel.

These men held a council of war and appointed Colonel William Campbell of Virginia as commander of the group. However, they agreed that the five would act in council to command their combined army. The Patriot force began hunting Ferguson and his loyalist militiamen. However, Major Ferguson received information from two frontiersmen, deserters, that the Patriots were on their way to exterminate them. Ferguson left his base camp and began a slow march toward Charlotte, where Lord Cornwallis had established his headquarters. When Ferguson first received information that the Patriot force was on the move, he delayed his departure from Gilbert Town for three days before marching south. During this inexplicable delay, Ferguson wrote to Cornwallis, requesting reinforcements. On October 1, Ferguson's force reached the Broad River in North Carolina, where the Major wrote another letter to Cornwallis, again asking for some reinforcements. By October 6, loyalists reached King's Mountain, one of a series of rocky, wooded hills near the North Carolina-South Carolina border. It is shaped like a footprint with the highest point at the heel, a narrow vamp, and a wide, rounded toe. Loyalists camped on a ridge west of King's Pinnacle, the highest point on King's Mountain. Ferguson's force was a day's march west of Cornwallis's command post at Charlotte. The patriots searched for Patrick Ferguson, after several false moves and some misinformation, the men heard that Patrick Ferguson had stopped his army at a place called Little King's Mountain. Since the mountain men were still some distance away, they decided to ride fast and hard to catch Ferguson. They divided his band into two groups: the first group of about 900 men would proceed quickly to King's Mountain. The second group, numbering about 500 tired after the almost 500km journey, could not move as fast and would join the patriot forces as soon as they could.

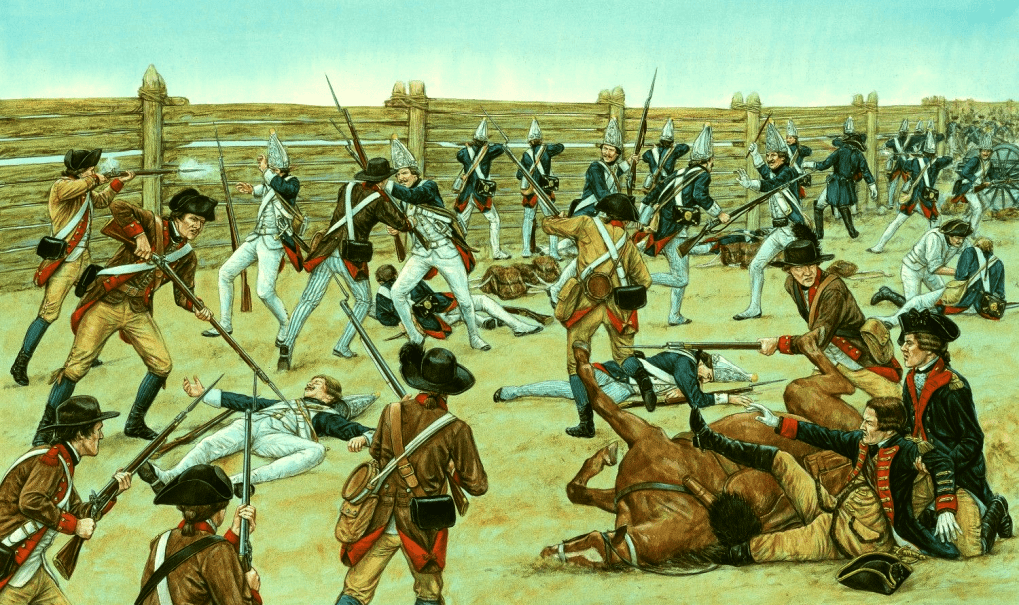

The first group set out on the night of October 6, the mountain men riding furiously through a rain storm, intent on arriving as soon as possible. At dawn on October 7, they crossed the Broad River, about 15 miles from King's Mountain. In the early afternoon they arrived and immediately circled the ridge. The battle began at about 3:00 p.m., when the 900 Patriots, including John Crockett, approached the steep base of the western ridge. They formed eight detachments of just over 100 each. Ferguson was unaware that the Patriots had caught up with him and his 1,100 men. He was the only regular British soldier, made up entirely of loyalist Carolina militia, except for the 200 enlisted provincials from New York, who wore red coats. He hadn't thought it necessary to fortify his camp. The patriots surprised the loyalists. Loyalist officer Alexander Chesney later wrote that he did not know the Patriots were near them until the shooting began. As the Patriots screamed up the hill, Captain Abraham de Peyster turned to Ferguson and said, "These things are sinister, these are the bloody screaming boys!" Two parties, led by Colonels John Sevier and William Campbell, attacked the heel of the mountain, the smallest in the area, but its highest point. The other detachments, led by Colonels Shelby, Williams, Lacey, Cleveland, Hambright, Winston and McDowell, attacked the main Loyalist position, surrounding the heel. No one in the patriot army was in command once the fighting began. Each detachment fought independently under the previously agreed plan to encircle and destroy the Loyalists. The patriots crawled up the hill and fired from behind rocks and trees. Ferguson rallied his troops and launched a desperate charge with fixed bayonet against Campbell and Sevier. Lacking bayonets, the patriots ran downhill into the woods.

Campbell soon rallied his troops, returned to the hill, and continued firing. Ferguson ordered two more bayonet charges during the battle. This became the pattern of the battle; the Patriots would charge up the hill, then the Provincials would charge down the hill with fixed bayonets, driving the Patriots off the slopes into the woods. Once the charge was spent and the Conservatives returned to their positions, the Patriots would regroup in the woods, return to the base of the hill, and climb back up the hill. During one of the charges, Colonel Williams was killed and Colonel McDowell was wounded. Shooting was difficult for the Loyalists, as the Patriots were constantly moving around using cover and concealment to their advantage. In addition, the downward angle of the hill helped loyalists outmaneuver their rivals. After an hour of fighting, loyalist casualties were severe. Ferguson crossed the hill from one side to the other, blowing a silver whistle that he used to point to. Shelby, Sevier and Campbell reached the top of the hill behind the Loyalist position and attacked Ferguson's rear. The loyalists were herded back to their camp, where they began to surrender. Ferguson drew his sword and slashed at the little white flags he saw appear, but he seemed to know the end was near. In an attempt to rally his hesitant men, Ferguson shouted "Hooray, brave boys, the day is ours!" He mustered some officers and tried to get through the patriot ring, but Sevier's men fired a volley and Ferguson was shot and knocked off his horse but luckily he was not pinned to his horse and therefore not being dragged by his horse behind the fence. patriot line. The Loyalists recaptured Ferguson as they regrouped.

With their leader wounded, the loyalists began to surrender. Some Patriots did not want to take prisoners, as they were eager to avenge the Battle of Waxhaws, in which Banastre Tarleton's forces killed a considerable number of Abraham Buford's Continental soldiers after the latter attempted to surrender. Loyalist Captain Peyster, under orders from Ferguson, sent an emissary with a white flag, asking for quarter. For several minutes, the Patriots repulsed Peyster's white flag and continued to fire. A significant number of the Loyalists who surrendered were killed or wounded, including the White Flag emissary. As de Peyster sent up a second white flag, some of the Patriot officers, including Campbell and Sevier, ran forward and took control ordering their men to stop firing. They took around 700 Loyalist prisoners including Ferguson. The Battle of King's Mountain lasted 65 minutes. The loyalists suffered 290 dead, 163 wounded and 668 taken prisoner. The patriot militia suffered 28 dead and 60 wounded. The Patriots had to leave quickly fearing that Cornwallis would come forward to meet them. Loyalist prisoners well enough to walk were herded into camps several miles from the battlefield. The dead were buried in shallow graves and the wounded were left in the field to die including Ferguson who, never having been seen by the patriots, was mistaken for a wounded Loyalist officer. Both victors and captives starved on the march due to lack of supplies in the hastily organized patriot army. On October 14, the retreating Patriot force court-martialed the Loyalists on various charges (treason, desertion from Patriot militias, inciting Indian rebellion).

Passing through the Sunshine community, the retreat stopped at the Biggerstaff family property. Aaron Biggerstaff, a loyalist, had fought in the battle and been mortally wounded. His brother Benjamin was a patriot and was being held as a prisoner of war on a British ship docked in Charleston, South Carolina. His cousin John Moore was the Loyalist commander at the earlier Battle of Ramsour's Mill, in which many of the fighting men at King's Mountain had taken part on one side or the other. While stopping at Biggerstaff land, the rebels sentenced 36 Loyalist prisoners. Some were declared against by patriots who had previously fought alongside them and later changed sides. Nine of the prisoners were hanged before Isaac Shelby ended the trial. His decision to stop the executions came after an impassioned plea for mercy from one of Biggerstaff's women. Many of the patriots dispersed over the next few days, while all but 130 of the Loyalist prisoners escaped as they were led single file through woods. The column eventually camped at Salem, North Carolina. King's Mountain was a turning point in the US War of Independence. After a series of disasters and humiliations in the Carolinas (the fall of Charleston and the capture of the US Army there, the destruction of another US Army at the Battle of Camden, the Waxhaws Massacre), the stunning decisive victory at Kings Mountain was a great victory, a boost to Patriot morale Carolina loyalists were destroyed as a military force In addition, the destruction of Ferguson's command and the imminent threat of Patriot militia in the mountains caused Lord Cornwallis to cancel his plans to invade Carolina Instead, he evacuated Charlotte and retired to South Carolina, not returning to North Carolina until early 1781. Ferguson was found by Tarleton's Legion who, due to his injuries, returned to England.

By the fall of 1780, Loyalist forces were on the defensive in Carolina, still reeling from their painful defeat at the Battle of King's Mountain in October 1780. With that Patriot victory, the Carolina country returned to their control, putting pressure additional on Cornwallis and Tarleton. Thus, instead of going after the elusive Patriot leader "Swamp Fox" Francis Marion, Cornwallis ordered Tarleton to harass Patriot militia units under the command of General Thomas Sumter. Cornwallis hoped that Tarleton could secure a victory and reinvigorate the Loyalist cause. By the end of November, Sumter's patriotic band had grown to 1,000 men. On 18 November, Tarleton's British Legion dragoons and 63rd mounted infantry were bathing and watering their horses in the Broad River when some of Sumter's militiamen fired at them from the opposite bank. The British brought out a 3-pound cannon and easily dispersed the raiders. But Tarleton did not tolerate insults easily. Putting his men across the river in flatboats at night, he pressed Sumter hard the next day. Fortunately for Sumter, a deserter from the 63rd regiment revealed Tarleton's plans and location. Although Sumter had 1,000 militiamen, Tarleton at that time only had a little over 500 under his command, including 300 British regulars, but he had never been defeated. Sumter and his colonels decided it was best to find a strong defensive position and wait for Tarleton to attack them. Colonel Thomas Brandon, who knew the area, suggested the nearby farm of William Blackstock, a farm in the hills above the River Tyger. The land had been cleared for farming, providing good fields of fire and room for manoeuvre, and the structures were of logs and thus narrow but convenient gaps could be cut for men firing from behind cover.

On 20 November, at 1000 hours, Tarleton followed his lead, advancing ahead of the 71st and the artillery, with 190 of his dragoons and his Legion's mounted infantry, and 80 mounted regulars of the 63rd. He met a force from Sumter at Enoree Ford which he dispersed with great slaughter. It was later claimed that the group were some Loyalist prisoners who had previously been in charge of some Sumter riflemen under Captain Patrick Carr. Carr escaped at the approach of Tarleton, and in the confusion Tarleton took the freed Loyalists as rebels. Tarleton discovered that Sumter was withdrawing forces from him. Tarleton found the Patriot force and pursued them throughout the afternoon. At 4:00 p.m., Tarleton knew that using all of his strength he could not reach Sumter. Therefore, he decided to take only 190 dragoons and 80 mounted infantry from the 63rd to continue the fast pursuit and let the rest of his force follow on his own. Within an hour, he had finally caught up with the rear of Sumter's force. Sumter had reached the Tyger River. At 5:00 p.m., with daylight fading, Sumter was worried about his situation. However, a local woman who had been watching the British entered Sumter's camp and informed him that British artillery and foot soldiers were still trying to catch up with Tarleton. Knowing that he was favored with good defensive ground, Sumter decided to hold out at the Blackstocks plantation. The river was on Sumter's rear and right flank, but on its left flank was a hill that had 5 log houses belonging to the plantation set in an open field. He ordered Colonel Hampton and his riflemen to defend the houses, and Colonel Twiggs Georgia's sharpshooters were placed along a fence that stretched from the log houses to the woods on the left flank.

On the wooded hill that rose to his right from the main road, Sumter deployed most of the rest of his troops. Colonel Lacey's mounted infantry was to protect the right flank and Colonel Richard Winn was sent to the rear, along the river, as a reserve. As Tarleton approached Sumter's position, he decided that the Patriot line was too strong to attack alone without the rest of the force straggling behind him. While he waited for the rest of the British force, Tarleton dismounted his infantry and sent them to his right flank which faced a stream running opposite the Sumter front. The dragoons were sent to his left flank. Sumter decided not to wait until Tarleton was reinforced to attack. Just before Tarleton arrived, Taylor's detachment lumbered into the camp with cartloads of flour taken in the raid on Summer's mill. Initially, Tarleton charged and drove off a group of Sumter's men positioned ahead of the main body. However, Tarleton later stated that he had no intention at the time of engaging Sumter directly, but rather that the battle came about as a result of some of Sumter's men (the Georgians) engaging his own. Sometime after 5:00 p.m. Sumter sent Colonel Elijah Clark and 100 men to encircle Tarleton's right flank and prevent reinforcements from joining him. Clark's force fired on the British too soon and the British counter-attacked and drove Clark back. At the same time, Sumter ordered Colonel Lacey to attack the British left flank. He was able to get within 75 meters of the British, who were busy watching the fighting to the left of him, and opened fire. His men quickly killed 20 British dragoons. The British regrouped and drove Lacey out. While riding from their right flank into the center, Sumter was hit by a musket ball.

He pierced her right shoulder, along the shoulder, and splintered her spine. After discovering that Sumter was wounded, Twiggs assumed overall command. The advance of the British reinforcements was halted as Tarleton's men were being fired upon from their flanks. Tarleton and his men were in a precarious position and suffered severely from the fire of the patriots. At that moment of peril, Lieutenant John Money led a bayonet charge that threw Sumter's men into disarray: Money himself was mortally wounded in the attack by Colonel Henry Hampton's riflemen. Tarleton then fell back 3.5 km to join his support column. In the British withdrawal from Blackstock, Major James Jackson and his Georgians captured 30 riderless horses, apparently those of the 63rd. By the time Tarleton had joined forces with the 71st Highlander, it was dark and it was beginning to rain. Major James Jackson in later years reported that the fight had lasted three hours. Colonel John Twiggs, who took immediate command of Sumter, who had been badly wounded, left Colonel Winn to keep some fires burning, while the remaining Patriots withdrew over the Tyger River. Sumter himself had to be carried off the field in a litter. For the next three days, Tarleton attempted to pursue Sumter. Although he managed to take a handful of prisoners, most of Sumter's men managed to escape in separate groups. What was left of Sumter's brigade was put in charge of Lt. Col. William Henderson, who had been taken prisoner at Charleston, and had recently been traded. Cornwallis reported to Clinton on December 3: “As soon as he [Tarleton] took care of his wounded, he pursued and scattered the remaining part of Sumpter's body; and then, having assembled a militia under the command of Mr. Cunningham, whom I made a brigadier-general of the militia of that district, and who has by far the greatest influence in that country, returned to the River Broad, where he now remains ; as well as Major M'Arthur, in the Brierley Ferry neighborhood."

As darkness finally engulfed the battlefield, both sides withdrew to the safety of their positions. Both sides then claimed victory for the battle. The patriots claimed victory because they had picked the fight and repulsed the British. Tarleton claimed victory because he was successful in his initial mission of keeping the Patriot force away from Fort Ninet-Six and dispersing the Patriots. He also put Sumter out of commission for a time. British casualties were 92 killed and 75 to 100 wounded. Patriot casualties were 3 killed, 4 wounded, and 50 captured. Sumter's injury was a blessing in disguise, as Congress finally relented to allow George Washington to designate his own choice for American command of the South. Washington appointed one of his best field commanders, Nathanael Greene, whose very presence tilted the Southern campaign in favor of the Americans.