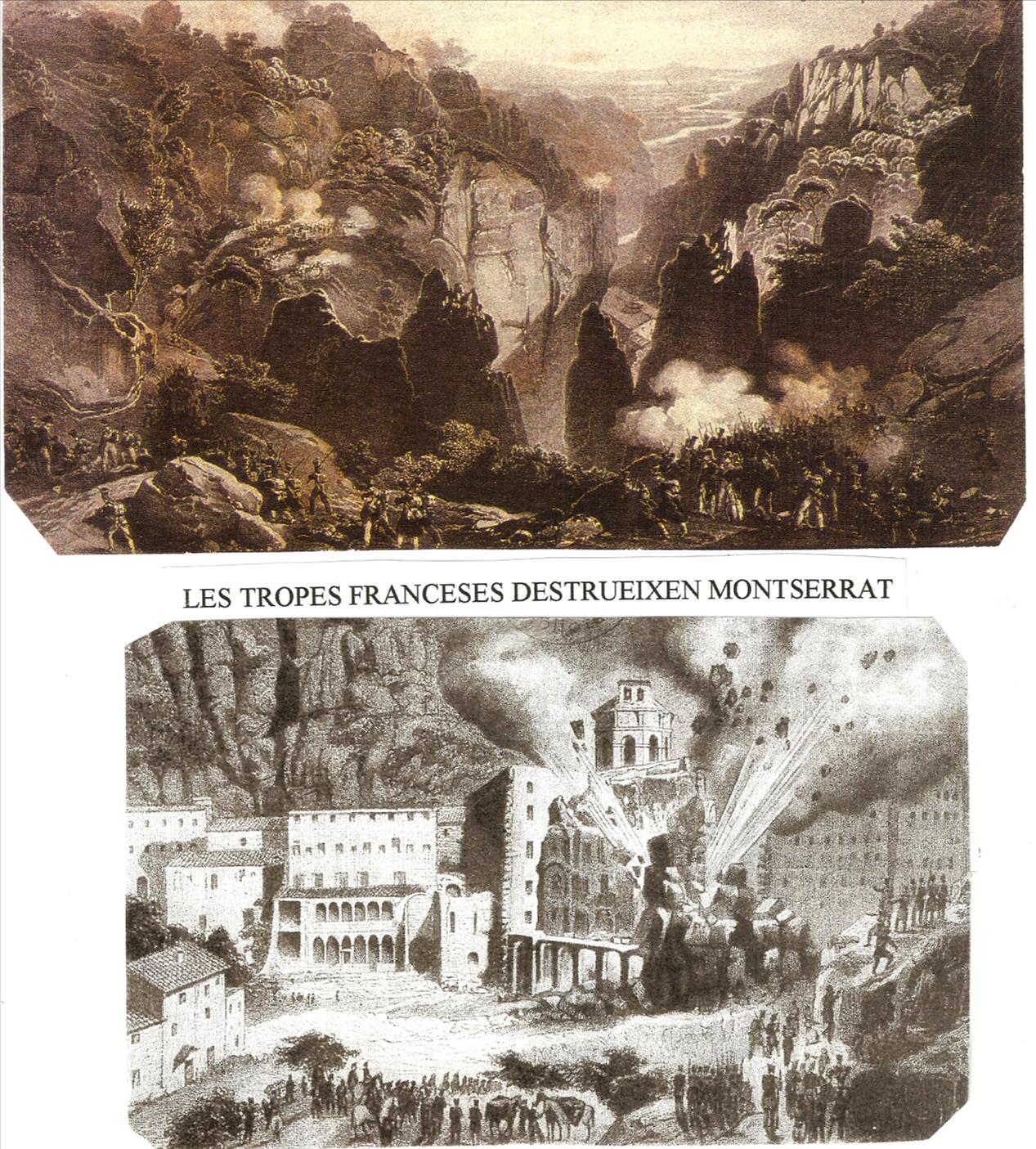

The war of the First Coalition in Europe saw how the French built several satellite states of the French Republic, being a continuation of the policy of creating sister republics in the neighboring territories of France. The policy adopted in the United Provinces that became the Batavian Republic was revolutionary and liberal, as well as very unstable, since several coups d'état took place during its short existence. Precisely the great political instability and the many coups d'état prevented the normal functioning of the country and its institutions. One of the few revolutionary policies that came to fruition was the abolition of the last remaining vestiges of feudalism in the former United Provinces. Nor could the Batavians carry out their project of establishing a democratic Constitution (with universal suffrage and a single Assembly) due to the interference of the French Directory, which was not interested in establishing a State with decision-making capacity and contradicting the interests of French foreign policy. In Italy, thanks to the brilliant command of General Napoleon Bonaparte, the Ligurian and Cisalpine Republics were established, which were satellites to the will of the Directory to economically exploit Italian territory to finance the wars in France that recognized French hegemony and with aspirations over the territory from the neighbors A notable fact would be that as the French revolutionary troops traveled through the enemy territories, they were living off the land, which included looting cattle, crops and any means that supplied the army in the campaign, this fact was accompanied by crimes that included rapes and murders. defenseless women and children; looting of cities and towns, without forgetting the indiscriminate burning of churches in front of the anti-clerical revolutionary.

Following the Treaty of Campo Fornio on October 17, 1797, which marked the end of the First Coalition, the victorious conclusion of Napoleon's campaigns in Italy only left Great Britain against the French. The French planned to invade England to establish a series of Republics (England, Wales and Scotland) naming Napoleon Bonaparte as head of the French army in England in October 1797, dedicating himself to planning since then how to invade the English coasts. After studying the operation for months, he discovered that the UK was excellently well protected by the Home Fleet, the naval squadron that guarded the English Channel, and that at that time it had better capabilities than the French Revolutionary navy. In February, Bonaparte came to the conclusion that in order to defeat the British one must first damage their economy, causing a loss of resources that harms them later; since the powerful Royal Navy required large sums of money to maintain itself, and if England neglected its fleets due to budgetary precariousness, it could be vulnerable in the short term. Napoleon proposed to the Directory that, instead of an invasion of England, the Middle East should be invaded, in order to cut the maritime and land trade routes with India from the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea to the Mediterranean; which would be a severe blow to the English economy, which would have a negative impact on its war effort. This undertaking would be possible because both the Turkish Ottoman Empire and its Mamluk vassals, owners of the lands to be occupied, were militarily inferior to France. The Directory, also thinking of removing the uncomfortable general from the country, agreed to give him the means he needed for his campaign, which would be prepared in the strictest secrecy so that the English could not send fleets to the Mediterranean, which was still considered a Spanish Sea thanks to the positioning of the Spanish naval bases: Cartagena, Palma de Mallorca, Cagliari, Syracuse and Tunis together with the support of the Order of Malta that offered anti-piracy and anti-Islamic proselytizing support.

From the beginning, Bonaparte required the presence of scholars in his expedition, with whom he will form a Commission of Sciences and Arts, since he insisted that his will also be an expedition of scientific conquest, in accordance with the ideals of the Enlightenment. He also justified this campaign arguing that it will serve to export the French Revolution to Egypt, freeing the Fellahin peasants from the yoke of the Mamluks. On April 12, Napoleon was appointed commander of the future French Army of the East, which would be in charge of carrying out the conquest of exotic Mamluk Egypt. In little more than a month, Napoleon had managed to secretly organize a force that he considered more than sufficient to occupy Malta and wrest Egypt and Palestine from the Ottoman Empire. The Army of the East is made up of 5 divisions commanded by Desaix, Dugua, Reynier, Bon and Vial with 14 half-brigades with 32,000 infantry, including 1,140 engineers, sappers and pontoons; a cavalry division commanded by Murat with 7 cavalry regiments with 2,700 horsemen; 171 cannons and mortars served by some 3,000 artillerymen, and a body of 480 guides. In total, about 36,180 men. Most of them did not know where they would be mobilized. In addition, Napoleon had aides-de-camp such as his brother Louis Bonaparte, Duroc, Eugène de Beauharnais and the Polish nobleman Sulkowski. The artillery consisted of siege artillery with 35 guns with 600 rounds per piece; 72 field (17×12, 2×11, 35×8, 6×5, and 12×4) with 500 shots per piece, 24 howitzers (4×8 and 20×6); 40 mortars (15×12, 4×10, ); with 248 wagons of ammunition. The Commission for Sciences and Arts of the Army of the East is made up of 153 of the best scientists and artists in France, including 21 mathematicians, 17 engineers, 13 naturalists, 10 writers, 8 draughtsmen, 4 architects and 3 astronomers, in addition to 22 printers equipped with presses and Latin, Greek or Arabic characters.

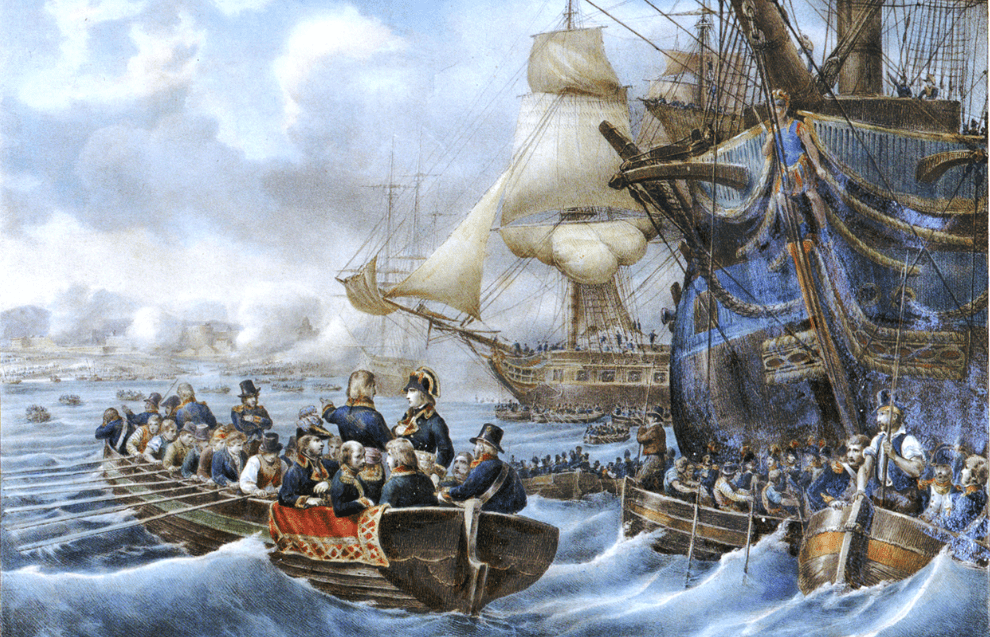

They ignore their destination, and they have only been told things like where they would "conquer glory and knowledge." On the Mediterranean coast of France, a large fleet discreetly gathered, distributed among several ports so as not to attract attention. It was made up of 455 ships escorted only by 4 frigates and 13 ships of the line (1×120, 3×80 and 9×64) in which some 16,000 men served, 2×34 and 8 Venetian frigates, under the command of Vice Admiral François- Paul Brueys D'Aigalliers. Just a few days before the departure date, the ships would congregate in the ports of Toulon and Genoa. Napoleon arrived in Toulon on May 9 to oversee the last phase of the operation. At 06:00 hours on May 19, the French fleet leaves the Toulon dock towards Malta, its first objective. The living conditions on board the ships were uncomfortable for military or civilians due to overcrowding and a shortage of food. Napoleon traveled on the Orient (120), the flagship of the squadron and one of the most powerful ships of the moment. French newspapers speculated on the mysterious fate of the fleet, reporting that it was heading for Ireland to attack Britain from there, a hoax perhaps spread by Bonaparte; What is certain is that these rumors puzzled British spies, who were speculating on India as other possible destinations for the French expedition. On June 7, 1798, Nelson set sail with his fleet, in pursuit of the French navy. On June 9, the French fleet carrying Napoleon's Army of the Orient landed on the northern coastal strip of the Mediterranean island of Malta, ruled by Hompesch, Grand Master of the Order of the Knights of Saint John, who had his headquarters in the walled city of Valletta. From the flagship of the French squadron, the Orient (120), Bonaparte requested permission from the Valletta authorities to moor his ships in the port and refuel with water. The Grand Master convenes a council of war and called all the knights to arms, who rushed to garrison the walls of the capital.

After arduous deliberations, Hompesch allowed the French to bring their fleet closer to the port in groups of no more than 4 ships at a time; it is true that about 200 knights were French and did not wish to fight compatriots. Napoleon embarked in a small boat and spent the rest of the day visiting the coastline and the outer fortifications. He realized that the cannons were old and made of iron. The Maltese forces were 2 battalions of 500 men; 200 Grand Master's Guards, 250 galley men; 250 troops from ships; 200 gunners or battery guards; in total 1,900 regular troops. This figure rose to 2,900 men, adding 800 hunters, 200 miners and sappers (recruited when necessary from the Maltese quarries); and a militia force estimated at 10,000 men. As Bonaparte would later write in his diary “the island is well endowed… there were 1,200 artillery pieces, 40,000 rifles, a million pounds of gunpowder in the square… The wheat reserves were very considerable; there was enough to feed the city (Valletta) during three years of siege”. On June 10 the French infantry made several landings. The landing in the bay of San Pablo in the north of Malta was carried out by troops under the command of Louis Baraguey d'Hilliers. The Maltese offered some resistance but were quickly forced to surrender. The French managed to capture all the fortifications overlooking St Paul's Bay and nearby Mellieħa without any casualties within a few hours. Casualties for the defenders consisted of one knight and one Maltese soldier being killed, and around 150 knights and Maltese were captured. The French force that landed on the island of Gozo was commanded by Jean Reynier. Gozo was defended by a total of 2,300 men, consisting of a company of 300 regulars, a regiment of 1,200 coastguards, and 800 militiamen.

The landing began around 1:00 p.m. in the Redum Kebir area in the vicinity of Nadur, between the Ramla Right Battery and Sopu Tower. The defenders opened fire on the French, and were aided by artillery from the batteries at Ramla and Sopu tower. The French managed to advance to higher ground despite the fire. The batteries at Ramla were taken, and the French managed to land the rest of their troops. Casualties among the invasion force was a sergeant major shot dead during the landing. The defenders took refuge in the Citadel, which surrendered at nightfall. The French captured some 116 artillery pieces. A force commanded by Louis Desaix landed at Marsaxlokk, a large bay in the south of Malta, the French managed to capture Fort Rohan after some resistance. After the capture of the fort, the defenders abandoned the other coastal fortifications in the bay, and the French landed most of their forces unopposed. Forces led by Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois landed in and around Saint Julian's. A galley, 2 galleasses and a sloop from the Order's navy set sail from the Grand Harbor in an attempt to prevent the landing, but their effort was futile. 3 Battalions landed, and were met by some companies of the Malta regiment who offered resistance before withdrawing to Valletta. French forces surrounded the city, linking up with Desaix's troops who had successfully landed at Marsaxlokk. The hospital defenders attempted a counter-attack by repulsing the French, who began to withdraw. The Hospitallers and Maltese advanced but were ambushed by a battalion of the line and were driven back in chaos. The French then began a general advance, and the defenders withdrew into the fortified town. With Valletta surrounded, Vaubois led some of the troops to the ancient city of Mdina, where the remaining militia had withdrawn after the landings.

Bonaparte offered the grand master a one-day armistice to surrender the capital. The fame of the French army and its Revolution had reached the island, and there were many Maltese who did not want to fight. At a town council in the Bishop's Palace, it was decided that resistance was futile and they agreed to capitulate if the religion, liberty and property of the people were respected. At around 12:00 noon, the terms had been agreed to by the representatives and Napoleon on the ship Orient, and the city capitulated to Vaubois. Malta would become part of the Republic of France, the Grand Master would receive a compensation of 300,000 francs, although he would have to cede the positions of power to the knights of French origin. The properties of the members of the Catholic Church and the Order would be respected under penalty of public death for those who broke that respect. Napoleon landed in Valletta on June 13, and stayed on the island for six days, spending the first night at the Banca Giuratale and then staying at the Palazzo Parisio. Thus ended the 268 years of government of the Order of Saint John in Malta, but not before raising certain complaints and displeasure on the part of the Spanish government, which is very close to Malta. Napoleon recognized that he would not have taken the capital without help from the interior, due to its magnificent fortification, and he installed himself in the Palazzo Parisio, naming General Varbois governor of the square, whose first task was to organize a commission to administer it. A few days after the capitulation, the grand master and many knights left the island, taking with them some possessions, including some relics and icons. The Order would flee to Carthage until it decided to be affiliated with the Spanish government as a semi-autonomous Militant Order. Such a leak would make Napoleon break his word and order the preparation of an inventory that includes the goods and assets of the treasure of the Order of Saint John, its palace and the churches, and ordered that everything that was not on the list or "it is essential for the cult" was requisitioned and shipped on the Orient and the Seriuse.

Jewellery, valuables and coins from the Order's treasury and churches were looted; the silver was melted down into bars and shipped. A few days later Napoleon already had a fortune that amounts to a quarter of a million pounds. Later the Order would be expropriated of its lands and income. The record of the looted wealth in Malta after the conquest of the island by French troops would be: Treasury of the church of San Juan 420,438 Ecus of Malta (59,953 in diamonds, 97,470 in gold, and 263,025 in money). Treasury of the church of San Antonio, dependent on the Order of San Juan 8,663 Ecus of Malta (703 in diamonds, 550 in gold, and 2,410 in money). In the palace of the grand master 52,976 Ecus of Malta (2,334 in gold and 50,642 in money). In the bank of the Island of Gozo 7,578 Ecus of Malta. Malta was a crucial link for France that will allow her navy to close the Mediterranean to the Royal Navy and supply her future conquests. However, in France it will not sit well at first, as not all of the government was aware that Malta was a target. Napoleon will have to justify his occupation to Talleyrand, French Foreign Minister. Bonaparte left a garrison of 4,000 soldiers in Malta, although he recruited 600 inhabitants with whom he formed the Maltese Legion, which would embark with the army of the East. Within three months, the Maltese rose up against the occupiers and took control of most of the islands with British help and Spanish volunteers. The French garrison at Valletta and La Cottonera held out the resulting blockade for two years, before Vaubois surrendered to the Spanish in 1800, making Malta a Spanish territory, the English being forced to cede as Malta was too near Sicily.

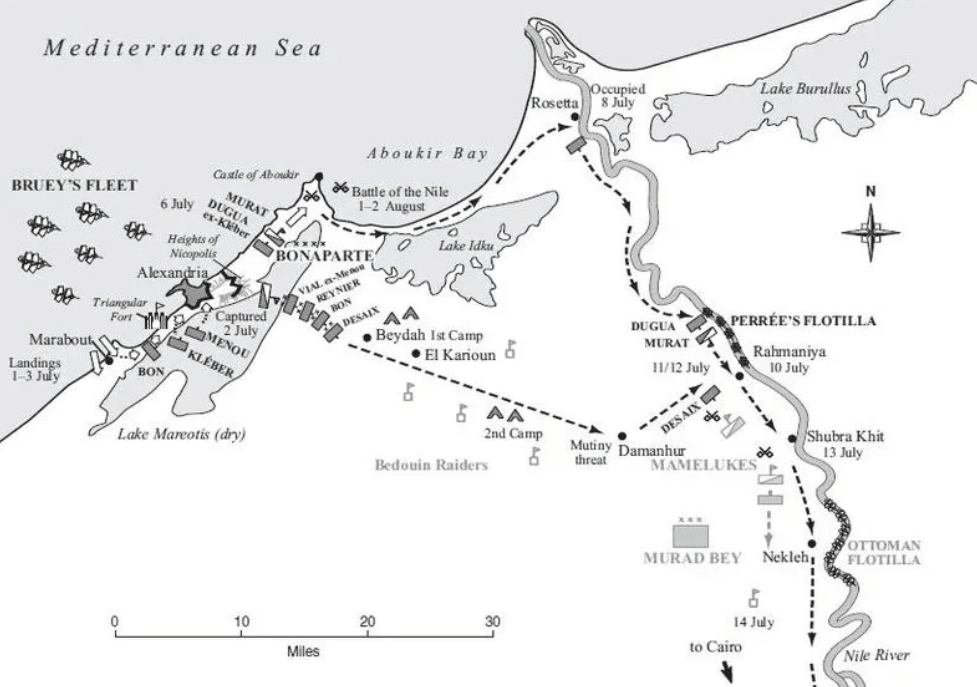

On June 18, Napoleon left the island. Soon the British admiralty found out where the French fleet was and sent after it the squadrons of Nelson and Admiral Jervis, who was near Gibraltar ready to close the passage of the Strait. On June 22, a schooner from Ragusa informed Nelson of the eastward departure of the French from Malta on June 16. After consulting with his captains, the admiral concluded that the French objective must be Egypt and headed there to begin the pursuit. Nelson insisted on taking a direct route to Alexandria with no detours because he believed the French had a five day lead, when in fact it was only two. On the night of June 22, Nelson's fleet overtook the French in the dark, unaware how close they were to their objective, partly also because of the fog. Thanks to having taken the direct route, Nelson arrived in Alexandria on June 28 and discovered that the French were not there. Following a meeting with the Ottoman commander Sayyid Muhammad Kurayyim, Nelson ordered the British fleet to head north on 30 June. It reached the Anatolian coast on 4 July and then turned west towards Sicily. On June 28, Napoleon revealed to his men that Egypt was the destination of his campaign. On July 31, the French Army of the East arrived in Egypt. Concerned by Nelson's closeness, Bonaparte ordered an immediate invasion; The troops landed by means of an amphibious operation in the Marabut bay, whose planning due to haste would be quite deficient and as a result 20 soldiers would drown. The French Army of the East, once landed, marched from Marabout for five hours to reach the port city of Alexandria. The rear of the column was assaulted by a party of Mamluks, capturing several soldiers and bartenders, to later subject them to all kinds of harassment: the men and women would be raped and beaten to later be sold as slaves without knowing more than their luck.

Before Alexandria, the French general Menou organized the assault on the triangular fort and the outskirts, while the divisions of Kléber and Bon entered the city through the Pompey and Rosetta gates. Resistance was light and by early afternoon the fighting had ended. General Menou received seven wounds while crossing the ramparts. Bonaparte offered an agreed surrender and freed 700 Arab slaves from Malta. During the rest of the day, Napoleon's troops distributed among the inhabitants printed copies of the revolutionary propaganda pamphlets that he himself had produced; in which it was said that the arrival of the French obeyed the will of Allah, who sent them to free them from the rule of the Mamluks, a minority military caste that had subjugated the fellhains, the Arab peasants of Egypt, for centuries. Bonaparte will observe with pleasure how the Egyptians welcomed the revolutionary ideals, hoping that they would tolerate the French and even help them fight against the Mamluks. Bonaparte then led the bulk of his army inland. He entrusted his naval commander, Vice Admiral Brueys, with the task of anchoring in Alexandria Harbor, but soundings indicated that the harbor channel was too narrow and shallow for the largest ships in the fleet. Consequently, the French selected an alternative anchorage in Aboukir Bay, 32 km northeast of Alexandria. The Egyptian army was composed of the Mamluk forces numbering 9,000 to 10,000 cavalry and about 20,000 infantry auxiliaries, and the Ottoman governor's forces composed of sipahi (sepoya) cavalry and Janissary infantry totaling about 20,000 strong.

On the other hand, there were the Bedouin Arabs from the desert tribes who were mainly engaged in harassing the columns and the fellahins who were armed with farming tools. The best troops were the Albanian and Libyan mercenaries, who were mainly infantry. The Mamluks preferred to persist in a traditional fighting style rather than adapt to new methods of warfare. Murad-Bey, then in charge of military affairs, tried to adopt a Western-style conversion policy. To face a possible return of the Ottomans, Murad decided to provide the Mamluk army with a river fleet, which must prevent any invasion by the Nile. The river was the economic heart of Egypt, and it had to be preserved from the invaders. However, the Mamluks were barely seamen, they had to recruit mercenaries to run the flotilla which would cause a lot of damage to the French. Murad entrusted the organization of his fleet to a Greek mercenary converted to Islam, Nicolas Papas Oglou. The crews were made up of Greek mercenaries and faithful to their leader. For artillery, Murad also turned to Greeks from Zante, the three Gaeta brothers, who had converted to Islam and even became Mamluks. They organized a cannon foundry near Murad's palace, and managed to provide Murad with light artillery. However, this artillery was very poor compared to the European one. The guns were mounted on marine mounts, which were made to fire at large, hard-to-miss targets, such as a ship. Mamluk field guns were also of very poor quality because they are made of iron. Therefore, the range was less and with intensive and prolonged firing, the iron tended to melt much faster. The guns were handmade and difficult to maneuver. Although the Mamluks are undertaking some reforms, they could not establish a tactic that would combine all the corps, that is, cavalry, artillery, infantry and the river flotilla.

This lack of combination would be fatal for them. Each corps operated independently in battles. In his thought pattern, cavalry was still the key element in defeating the enemy. In Europe, the cavalry was no longer the main breaking point. From Agincourt, the infantry increasingly tended to dominate the battlefield. After landing at Marabout, completely surprising the Mamluks and leaving a garrison in Alexandria, 25,000 soldiers and 35 light guns of the French Army of the Orient under Napoleon began a march south along the west bank of the Nile, to reach El Cairo, the capital of the Mamluk government. Degua and Murat's divisions advanced through Abukir, Roseta and up the Nile to Rahmaniya where they would join up with the main army. But the French had not been prepared to withstand the climatic rigors of the country. Their European uniforms gave them stifling heat, accentuated by the weight of the equipment. Their diet was mainly dry biscuits, so they soon began to go thirsty. The Arabs poisoned the wells and the French fell ill shortly after with dysentery and cholera among other ills, many of them ending up questioning why Bonaparte punished them by leading them to that hell; some ended up committing suicide out of despair. On July 9, many soldiers planned to rebel and Napoleon managed to impose discipline, warning that deserters would be shot; General Mireur was found dead. The Mamluk beys or governors react by calling their fellahin peasants to arms. Bey Ibrahim concentrated around Cairo some 40,000 warriors, but mostly on foot and armed in the Turkish style, with sabers, axes or spears, but very few with muskets, and what is worse, they lacked military training.

On July 3, shortly after the French landed, Bey Murad mobilized a force of cavalry, which, despite appearing exuberant in colorful clothing and jeweled weapons, were similarly equipped to infantry, although each mamluk usually carried 2 pairs pistols. A flotilla under the command of Captain Perree made up of the xebek Le Cerf, 3 gunboats and 1 galley, was sailing along the Nile parallel to the army, and on June 13, was attacked by an Egyptian flotilla of 7 djermes (Egyptian vessels of 2 or 3 masts) manned by Greek sailors, attacked the French. In a short time, the 2 gunboats and the galley had to be abandoned by the French when they were outnumbered, leaving only the xebec and the third gunboat, which were loaded with civilians and soldiers who had abandoned the other ships. These were attacked from the Mamluk flotilla, along with small Turkish guns and cannon from the shore. However, Xebek Le Cerf scored a well-aimed shot at the Mamluk flagship, which caught fire and exploded. By this time the Mamluk ground forces were about to charge again, but the explosion sank part of the flotilla, leaving the forces grounded. On land, after hearing the first shots of the naval battle, he ordered his troops to attack the town (Bon's division), garrisoned by a few cannons and 4,000 fellahines, meeting the enemy advancing from the south head-on. Bonaparte had about 20,000 men divided into 5 divisions. Desaix's and Bon's divisions faced the enemy while Reynier's, Dugua's and Vial's divisions lined up as far as the river. Mourad-Bey had between 3,000 and 4,000 cavalry, supported by 20 guns and 2,000 Janissaries on foot.

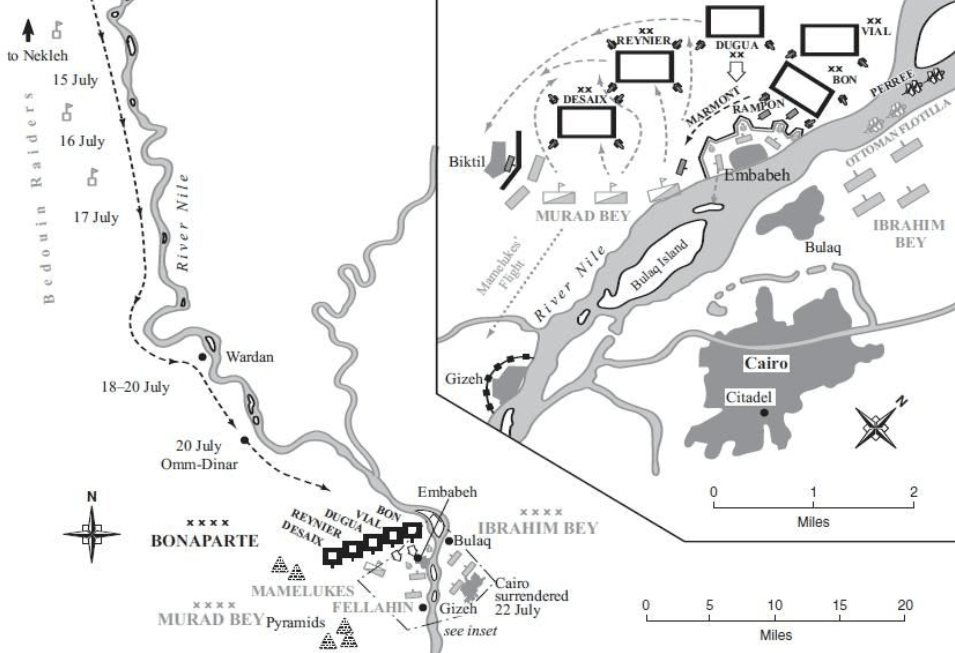

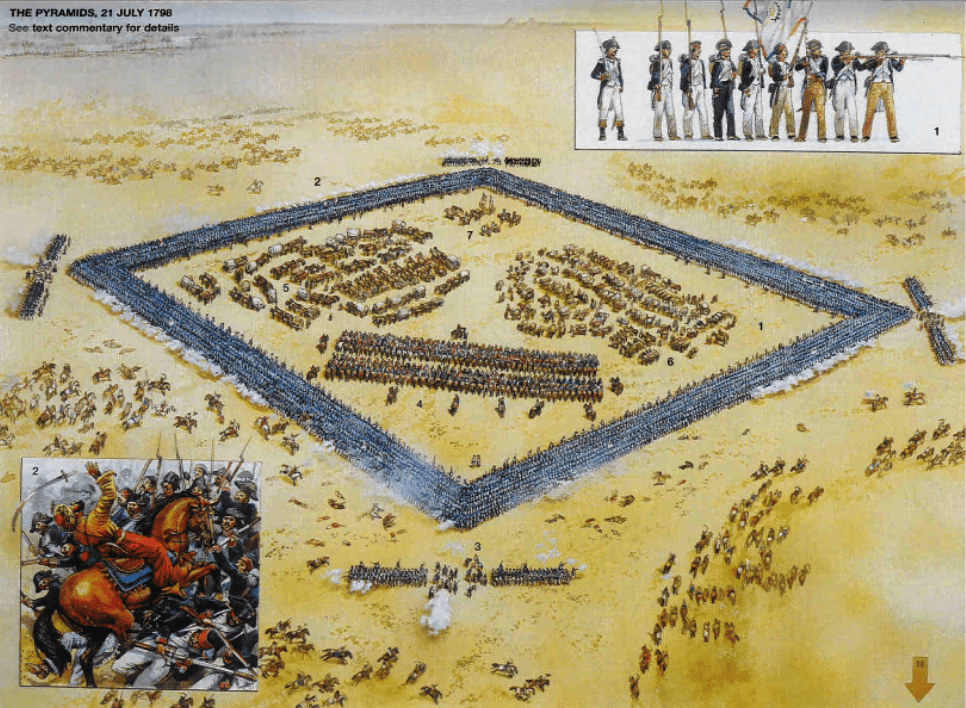

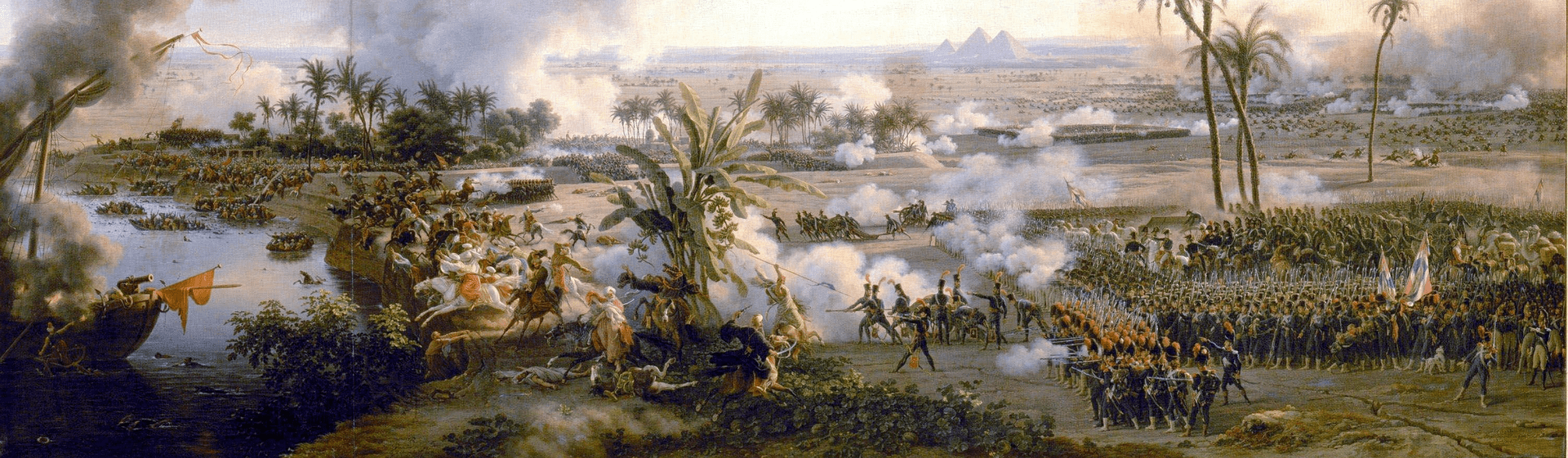

To repulse the Mamluk cavalry, which greatly outnumbered the French cavalry, the French formed their divisions into infantry squares 6 to 10 ranks deep with a small group of cavalry and baggage in the center, with the artillery in the center. the corners. For about the first three hours, the Mamluks rode in a circle around the squares, looking for an opening to launch their attacks. Then, when the French and Egyptian flotillas had finished their battle and moved away, the Mamluks attacked. These were immediately stopped by fire from the French artillery and infantry. The Mamluks regrouped and attacked a different square, but were again stopped by French artillery and infantry, but always out of rifle range. As a result the 14th Dragoon Regiment was unable to catch up with them in pursuit, and for the most part the cavalry remained within the squares. After an hour's defense, Napoleon ordered his troops to attack the village to relieve the naval flotilla, pushing back the Mamluks who were eventually forced to retreat. The Mamluks left about 1,000 dead and wounded, while the French had 20 wounded and 9 dead. On July 15 they left the village of Shubra Khit and five days later they had reached Omm el Dinar, at the tip of the Delta, where the Nile divides into two branches. On the 21st, with the first rays of the sun, the army left Omm el Dinar at 2:00 a.m. after breaking camp, and 12 hours later, at 2:00 p.m., they arrived at the village of Embabeh, at the height from Cairo. On July 21, the beys Murad and Ibrahim met the French near the pyramids of Giza, deploying 6,000 of their good horsemen and 8,000 inexperienced infantry on the west bank of the Nile; They positioned another 7,000 fellahins and 40 artillery pieces in the fortified village of Embabeh, while on the other bank 18,000 fellahins waited on foot under the command of Ibrahim-Bey. Murad had made a big mistake in placing his troops on the left bank of the Nile, saving the French from having to cross the river under fire to attack it.

Ibrahim-Bey would have to cross the Nile River to help if something went wrong for Murad-Bey. When General Bonaparte was informed about the position of the enemies and the advantage that the two beys had given him, he decided to engage in a decisive battle. Around 2:00 p.m., Bonaparte first saw the town of Embabeh, about 13 km away from Giza and its pyramids. After giving his troops only an hour to rest, Bonaparte was ready for battle at 3:00 p.m. To harangue his demoralized troops, Napoleon reminds them that they will go down in history: – “Soldiers…! From the top of these pyramids, forty centuries contemplate you…!” After 12 hours of marching under the hot Egyptian sun, the tired, hungry and thirsty French soldiers saw the Mamluk army in the positions Bonaparte wanted them to be, and the great pyramids of Giza before them. Knowing that Mamluk tactics were based solely on massive frontal charges by his brutal cavalry force, Napoleon ordered his 5 infantry divisions to deploy in a square, each side defending a half-brigade in 6 deep ranks, in the front ranks the soldiers carry fixed bayonets. Inside each box, the carriages of impediment and the cavalry were located, the artillery in the corners of the boxes. The French cadres form an oblique line in a northeast-southwest direction, with Bon's division on the left wing, to the northeast near the Nile, the Vial, Dugua and Reynier Divisions in the center, and the Desaix Division on the far left. right, southwest ahead. Napoleon with his staff stood with his staff in Dugua's Central Division, which gave him the greatest protection against any flank attack and at the same time allowed him to see the two divisions on either side.

The French divisions advanced south in echelon, with the leading right flank and the rear left flank protected by the Nile. The French troops had additional support from a flotilla of 15 riverboats, manned by 600 sailors under the command of Captain Jean-Baptiste Perree. Desaix's division approached the village of Biktil, and Desaix sent a small detachment of cavalry and grenadiers into the village, they climbed on the flat roofs of the houses and began shooting at the Mamluks, while Bon's division headed into the village. from Embabeh, which was fortified and held with infantry and some old cannons. At 3:30 p.m., the impressive Mamluk cavalry under Murad-Bey bravely charged the French cadres of Reynier and Desaix. They were forced to split into three columns to pass between the two squares, gripping the reins in their teeth as their pistols were fired at them, but the defenders' close-knit volleys broke up the assault before they could come up and use their scimitars. The horsemen turned to regroup, but began to receive fire from the cannons of Dugua's cadre, having to move away to start another attack, repeating the scene several times. The most important thing for the French was to maintain their solid infield formations. If the square broke through on one side, things would be very difficult for them, and hand-to-hand combat would favor the Mamluks. The French held fire until the screaming Mamluks approached to a distance of a few yards, so that not a single cartridge was wasted. Dead and wounded men and horses began to pile up around the French squares, but the Mamluks continued to attack for about an hour despite their heavy losses. Although the Mamluk cavalry charges were largely unsuccessful against the cadres of Bonaparte's divisions, they repeated the tactic over and over again, as if determination could overcome French firepower.

At times during the furious attack some Mamluks managed to break into the square, only to be mowed down by bayonets and rifle butts. The Greek Mamluk, Hussein, charged a square, making his way inside, receiving several wounds, but survived and would join the French army later. However, this suicidal bravery of the Mamluks could not help them against the continuous fire of the experienced European troops. As the Mamluks continued to charge and fall back, a curious encounter took place. A white-bearded Mamluk rode his horse mockingly making challenges in front of Bon's painting, on the far French left. Lieutenant Nicholas Desvernois stepped out of the box to accept the challenge. Like two medieval knights on a field of honor, they faced each other and closed the distance. Desvernois's first pistol shot dismounted the romper. Crawling on his hands and knees, his beard trailing the ground, the Mamluk used his scimitar to slice off the legs of the lieutenant's horse. The battle continued on the ground until Desvernois's saber struck the Mamluk's head, incapacitating him. The soldiers ran out of the square to finish off the overalls with the butts of their rifles. Desvernois was richly rewarded. The numerous pieces of gold sewn into his enemy's clothing and a magnificent sword, inlaid with gold on the hilt and rhinoceros horn scabbard, became the property of the victor. Before long, the corpses of hundreds of Mamluks and their mounts surround the French cadres, hardly suffering any damage apart from a spear or pistol shot. A little later Bonaparte ordered Vial's division to support Bon's division in its attack on Embabeh. Under the covering fire provided by his river flotilla.

The French were attacked by cannon hidden in the village. But the guns, which were mounted on fixed mounts that prevented them from moving across the battlefield, proved ineffective in stopping the attack. Bon formed several columns that stormed the town and took it, driving the horsemen towards the Nile and cutting them off from their fellahin infantry. Some 1,000 Mamluks drowned, and another 600 are shot dead trying to reach the eastern shore. After another hour of fighting, the Mamluks realized that their way of fighting was inferior to that of the French, with more modern weapons and tactics; so continuing the battle with such a great disadvantage would only increase his massacre, opting to retreat. Some 3,000 horsemen and 2,000 Mamluk warriors are killed or wounded, while the Army of the East has 29 soldiers killed and some 260 wounded. The army of the beys withdrew divided: Murad fled to the south and Ibrahim to Sinai, Lower Egypt was left defenseless. On the same afternoon of July 21, the bulk of the French army moved towards Giza, arriving with the last light of sunset. During the night, within sight of the pyramids, the soldiers drank, sang, and danced in celebration of victory; while in Cairo its inhabitants fearfully awaited what fate was going to bring them. Those who had enough wealth would buy a donkey or a starving camel, load their wealth and possessions on it and try to escape from the city; only to fall into the hands of bands of Bedouins and deserters, who stole everything they owned, raped the women, and in many cases murdered the men after sodomizing them. Bonaparte had arrived at Giza under his escort, and had spent the night in one of Murad-Bey's mansions. When he got up the next morning, he could see from his window the walls of Cairo, undoubtedly the most populous city in Egypt, with more than a quarter of a million inhabitants (similar to Vienna or Moscow), of which about 50,000 they belonged to the civil service of the Ottoman administration.

These were considered very dangerous by the more orthodox Islamic religious, who saw in them a new social class that seemed to have less respect for Islamic traditions than was due. The imams of Cairo will decide to surrender the capital without a fight, Napoleon entered Cairo on July 24, and took residence in the palace of Muhammad Alfi-Bey, an ostentatious building with magnificent gardens whose ponds and pools communicated directly with the river Nile. Napoleon allowed his soldiers to visit the pyramids and enjoy great freedom to mix with the population. Bonaparte did not want to waste time, and by July 27 the new administrative system tested in Alexandria was introduced in Cairo; a diwan (council) directed each province, supported by an agha (police chief), all of them under the supervision of a superintendent, a high-ranking French officer, in charge of collecting taxes from merchants and taxes on the transport of merchandise . Hygiene measures that the French considered absolutely essential for public health (cleaning the streets, lighting houses at night, closing cemeteries located in the center of Cairo, etc.) were flatly rejected by the Egyptians, who they saw such measures as a provocation. The conversion of the Cheraibi mosque into a tavern, and the new equal status given by the French to the Copts (Egyptian Christians, considered inferior by Muslims) would lead to an inevitable confrontation when the French transgressed any Islamic religious law. The reaction would undoubtedly be violent.

Nelson's fleet reached Tripoli on July 19, where it obtained the essential provisions to continue its mission. On 24 July the resupply of the fleet was completed and, having determined that the French must be somewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean, Nelson again set out for the Morea. On July 28, when he was in Coroni (Morean peninsula), Nelson was informed by Troubridge of the French attack on Egypt and headed south towards Alexandria. His advance guard, consisting of the Alexander (74) and the Swiftsure (74), finally sighted the French transport fleet at Alexandria on the afternoon of 1 August. The French squadron consisted of 13 ships: Orient (120), Franklin (80), Guillaume Tell (80), Tonnant (80), Guerrier (74), Timoleon (74), Conquerant (74), Aquilon (74), Spartiote ( 74), Peuple Souverain (74), Heureux (74), Mercure (74), Genereux (74); 4 frigates Diane (48), Justice (44), Artemise (36) and Serieuse (36). The fleet was commanded by Admiral Brueys D'Aigalliers, formed in a line close to the coast, with all their guns pointed at the open sea and sheltered by shoals, in such a way that they cannot be flanked and attacked from the rear, forming a true battery. floating of 1,194 guns. Aboukir Bay is a 30 km wide coastal indentation that stretches from the town of Aboukir in the west to Rosetta in the east, where a mouth of the Nile River is located. In 1798, the bay was protected by the west by long rocky banks that penetrated 4.8 km into the bay from a promontory on which the castle of Aboukir stood. A fortress located on an island between the rocks protected the rocky banks. The garrison of the fortification, equipped with at least 4 cannons and 2 heavy mortars, was manned by French soldiers. Brueys had reinforced the fortress with bombards and gunboats, anchored among the rocky shoals to the west of the island in an optimal position to support the head of the French line.

He deployed his ships in two lines, in the first line the 13 ships of the line with the Orient (120) in the center, and in the second line the 4 frigates, the sloops Salamine (18) and Railleur (18), the bombard Hercule and the Oranger and Portugaise gunboats, to avoid being engulfed. The 150 meters of space between each ship in the first line was wide enough for a British ship to break through and break through the French line. Also the French ships had only provided for the use of the guns on the sea side, leaving the guns on the other side fastened. At 2:30 p.m., the English fleet reached the bay. Nelson plans to concentrate his attack on the first ships of the Gallic line, to have a 2 vs 1 superiority at first. He hopes to destroy the French vanguard or at least outrun it, to outflank their formation and attack them from both sides. Nelson had 14 ships of the line: Vanguard (74) which was the flagship, Orion (74), Culloden (74), Bellerophon (74), Minotaur (74), Defense (74), Alexander (74), Zealous ( 74), Audacious (74), Goliath (74), Theseus (74), Majestic (74), Swiftsure (74), Leander (50); and the brig Mutine (18). In total it had 1,130 guns. At 4:30 p.m., Nelson's squadron began to maneuver to place half of his fleet in the open sea, attacking parallel to the vanguard of the French line. Meanwhile, several British ships, headed by Goliath (74), whose captain, Foley, had a map of Aboukir Bay that indicated that the actual depth of the shoals was greater than that known to the French. The wind changed direction and blew from the northwest, which benefited the British and hurt the French, who moved away from the shore. This caused him to leave enough space for Goliath (75) and the ships that followed, Theseus (74), Audacius (74), Orion (74) and Zealous (74) to flank the French formation passing between Guerrier ( 74), which was the first ship of the French formation, and the shore.

Around 5:30 p.m., Goliath (74) managed to overtake Guerrier (74) followed by Theseus (74), Audacius (74), which attacked the first three French ships. The frigate Serieuse (36) with the bombard Hercule tried to prevent the maneuver. The convention on naval warfare of that time stipulated that ships of the line not attack frigates in case there were ships of the same size that they could face; but when the frigate opened fire against the Orion (74), and this fired at it, it left it completely dismantled and would later sink. In total, 5 English ships managed to surround the French line, cannonading it from the narrow arm of the sea that separates them from the shore; while other English ships, led by Nelson's Vanguard (74), attacked her from the open sea, slowly annihilating her for the rest of the afternoon, the French being caught between two fires. At 18:45 hours, the first five ships of the French line were shelled on both sides by 8 British ships, suffering very serious damage, while the rest of the French formation was practically inactive. At around 8:30 p.m., a splinter struck Nelson's forehead, whose right eye was already damaged. The splinter caused a small tear in the skin that left him blind for a few moments. The admiral fell into the arms of Captain Edward Berry, who took him inside the ship. Nelson, sure that the wound was serious, shouted: "They have killed me, give my love to my wife", and called his chaplain, Stephen Comyn. The Vanguard's surgeon, Michael Jefferson, immediately examined the wound and informed the admiral that it was a simple tear and sutured the wound. Nelson then disobeyed Jefferson's orders to stay at rest and returned to the deck. Around 9:00 p.m., the French ship Guerrier (74) lowered her flag, practically destroyed. The French captain of the Tonnant (80), Commodore Aristide-Aubert du Petit-Thouars, stood out for his courage in the hard fighting that took place when he led his crew until he bled to death, without his legs and one arm.

The Tonant (80) would surrender at 23:45. At 9:30 p.m., the fifth French ship Peuple Souverein (74) was attacked by Defense (74) and Orion (74), was dismasted and withdrew towards land. The British ship Leander (74) turned and took up its position, splitting the French line in two and shelling the Franklin (80) from the stern, causing very serious damage, and the Orient (120) from the bow, which in turn was attacked. by the Leander (74) by the stern. Bellerophon (74) approached Orient (120) and released a broadside that partially riddled her hull, disassembling some pieces on the lower deck. Orient's response meant a carnage on the English ship, dismasting it almost completely. In this exchange of shrapnel, the Englishman received the worst part, since after 20 minutes he was adrift, and involuntarily approached at gunshot. With half her crew out of action and Captain Darby himself badly wounded, Bellerophon (74) was an almost immobile target. Two more volleys from the French ship at point blank range left her flat as a pontoon. Of her 590 men, nearly 200 were casualties. The Alexander (74) managed to position itself in line and discharged 30 double shots that ruined the rear gallery and part of the shrapnel wounded Admiral Aigailliers in the thorax. In less than 3 minutes, another volley littered with corpses. The French flagship was under fire from 3 British ships the Alexander (74), Swiftsure (74) and Leander (50). Orient (120) was apparently receiving a coat of paint on her hull and some of her canisters still remained open, being highly flammable and caught fire in the battle. Once the fire started, the British ships concentrated their fire on the burning area, preventing effective firefighting. Quickly, the fire in the Orient (120) lit up the entire bay.

It became apparent that the French flagship was doomed, her crew jumped into the sea, the British ships turned away, drenching their woodwork and rigging with seawater. Nelson, recovering from the wound below him, was called to the deck of the Vanguard (74). At 10:00 p.m., the Orient exploded. The sound was heard by French troops at Rosetta 40 km away and the crews of other warships thought their own ships had exploded. Admiral Brueys died instantly. Of the 1,000 crew members on board, the British only rescued 60, and with their companions the Maltese treasure that would finance Napoleon's campaign sank in Abukir Bay. At 11:45 p.m., the Tonant (80) and the Franklin (80) surrendered. The fighting continued through the early morning, slowly declining with cannonades, boardings, surrenders, and exchanges of fire; the ships Artemise (36) and Timoleon (74) burned until they were consumed. The resistance on the French ships ended around 06:00. At dawn Guillaume Tell (80) and Genereux (74) cut their cables and headed out to sea under Admiral Villeneuve, accompanied by the frigates Diane (48) and Justice (44). The Zealous (74) attempted a pursuit of the fugitives, but was soon withdrawn. The French had 1,700 dead, another 1,500 wounded, of which a thousand were captured along with 2,500 other men. 3,000 prisoners were returned to the commander of the port of Alexandria, since the British fleet could not serve them, Bonaparte later ordered these to form an infantry unit and added them to the army. The officers were taken aboard the Vanguard (74). The French lost 1 ship sunk, 2 ships burned and 9 ships captured, only 2 ships of the line and 2 frigates were saved. The British had some 218 dead and 678 wounded, not losing any of their ships and they had also captured 9 French ships of 74 or 80 guns.

The ships of the British fleet suffered little damage overall, although Bellerophon lost her three masts and Majestic her main mast. No other British ship lost a mast, although virtually all had minor damage. A few ships, including Bellerophon (74), Majestic (74) and Vanguard (74) had sustained hull damage. On August 8, the boats of the British fleet assaulted the island of Aboukir, which surrendered without resistance. The group that landed on the island withdrew 4 of the cannons and destroyed the rest along with the fortress they were in. In addition, he renamed the island "Nelson's Island". The British fleet would blockad Egypt, preventing the Army of the East from being reinforced or receiving supplies from France, leaving it isolated. Nelson will obtain as a reward on November 20 the title of Baron of Bath and a pension of 10,000 pounds per year. Thanks to him, the Royal Navy would predominate from then on in the eastern Mediterranean based on the island of Cyprus. For the French navy it is a tragedy, as it has lost its Mediterranean fleet. For Napoleon it means the ruin of his plan against England. When he found out what happened, he said: "So this is the end of my army... Am I destined to die in Egypt?" The only good news was on August 18 when the French ship Généreux (74) captured the English ship Leander (50), near Crete. The Ottomans, with whom Bonaparte intended to establish an alliance once his control of Egypt was complete, were encouraged to go to war against France after France was defeated at the Battle of the Nile. This led to a series of campaigns that little by little they were weakening the French army trapped in Egypt. Napoleon had control of Egypt despite the defeat: Kléber dominated the Nile delta, Manou took the port of Rosseta, and Desais pursued the Mamluks in Upper Egypt.

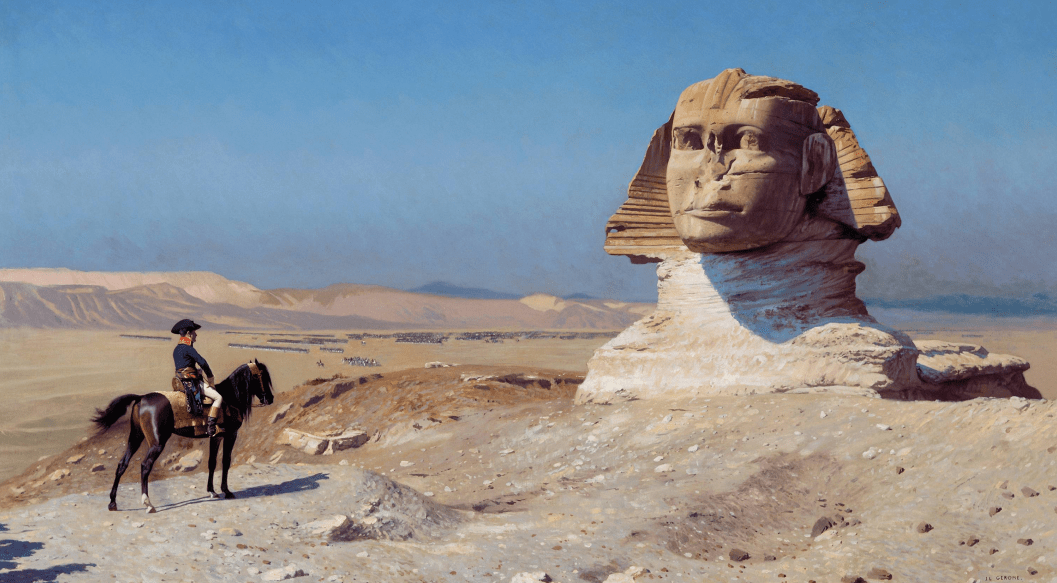

Napoleon founded the Institute of Egypt in Cairo, organized into four sections: mathematics, physics, political economy, and literature and arts, each with 12 members. The initial tasks entrusted to the scientific body were far from being studies of pure science: in the first session of the Institute, according to the minutes, topics such as improving the baking of bread or making beer without hops or how to clarify and cool the water of the Nile. Soon those initial topics would lead to more scientifically interesting ones. The works of the sages, published in the Egyptian decade, often leave the military completely indifferent. To the point that some decided to baptize the Egyptian donkeys with the name of "semi-wise". This will be the base of operations for French scholars and scientists in their research in the country, which in practice will mean the rediscovery of the wonders of ancient Pharaonic Egypt and the birth of Egyptology as a branch of archaeology. The results of the findings made by the scholars of the Institute would be published in a monumental work of 907 plates called "Description de L'Égypte" (Description of Egypt), which required 25 years to print, involving more than 200 illustrators who will make more of 3,000 images. Engineers and geographers would draw a 1/100,000 scale atlas of the land of the pharaohs on 47 sheets. Botanists and naturalists will send dozens of exotic plants and animals to France. This knowledge would cause shock in Europe, but led to the looting of the Egyptian cultural heritage. The scholars would adapt to the Arab country, although some thirty of them died in combat or victims of diseases, especially the plague. But the French administrators would not limit themselves to scientific research: they ended feudalism and generalized the collection of taxes to finance local projects, such as the construction of large infrastructures; the engineer Lepére would begin to plan a canal that would unite the Red Sea and the Mediterranean through the Isthmus of Suez.

In the summer of 1801 the British took Cairo and Alexandria. They demanded that the Institute hand over all its studies and documents. The French flatly refused: "We are prepared to burn our treasures as long as they do not fall into the hands of the enemy," said Geoffroy Saint-Hilarie. The determination of the French impressed the British forces. However, they managed to seize many works, including the famous Rosetta stone. The Rosetta Stone was discovered on August 20, 1799, when a French military detachment was doing repair work at Fort Julien at El-Rashid (called Rosette by the French) on the northern coast of Egypt. A soldier discovered the famous black stone, Engineers Lieutenant Pierre-François Bouchard, unearthed the granite stone weighing about 760 kilos; which turned out to be a large granodiorite stela with a decree made in the year 196, under the reign of Ptolemy V. As usual in this type of document, the text was written in the three official scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic and Greek. The Stone was immediately sent to Alexandria and later transferred to Cairo, where it was kept in a kind of archaeological museum that had been improvised in the Institute of Egypt. The incipient collection would gradually expand throughout the campaign. Two decades later it turned out to be a key element in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics. Jean-François Champollion never worked on the original, but on French tracings.

Within a month Napoleon had taken control of the country: Kléber dominated the Nile delta; Menou had taken the port of Rosetta; Desaix was persecuting the Mamluks in Upper Egypt; while the wise men, going up the river, explored Aswan, Thebes, Luxor and Karnak. However, the situation had become complicated after Abukir's defeat. The Ottoman Empire made a pact with the British and declared war on Napoleon. As if that were not enough, the growing Egyptian rejection led to a bloody uprising in Cairo that cost the lives of 300 Frenchmen. The revolt ended when Bonaparte turned his guns on the El-Azhar mosque and destroyed it. He had won, but the looting, rape and mass executions only served to increase hatred against the French and by extension against their allies, the Coptic and Orthodox Christians of Egypt. Napoleon was isolated. As he did not have his fleet, he could not receive supplies from the metropolis nor could he request help from the Spanish who had been displeased after the occupation of Malta. However, his army was intact and he decided to continue with his plans to conquer Palestine and Syria as a first step on his way to India, where he planned to arrive in the spring of 1800. In February of the previous year, shortly after Desaix had reduced the Last Mamluk pockets in Aswan, Napoleon left for Syria at the head of 13,000 men. His first objective was to finish off Djezzar Pacha —who was forming an army to reconquer Egypt— as soon as possible, because he had received news that the British intended to land an Ottoman contingent in his rear. But he was not going to have it easy. Crossing the Sinai desert was a difficult test that weakened the strength of his men. El-Alrich was taken, but after ten days of fighting. Shortly after, in Jaffa his plans were again delayed by strong resistance from the Ottoman garrison. When it surrendered, the French verified that it was the same one that they released in El-Alrich under a promise not to take up arms again.

As if that were not enough, a cholera epidemic broke out that began to wreak havoc among the French troops. Once Haifa had been taken without resistance, Napoleon, on his way to Damascus, headed for San Juan de Acre, an old Crusader fort. Again Djezzar Pacha's men offered resistance. Napoleon besieged the city. On one occasion the French were able to break through the walls and into San Juan de Acre, but Djezzar's troops repelled the attack. The defenders had the support of the British fleet, which supplied them with food and ammunition. One of the dramatic events of the siege was that Djezzar Pacha, nicknamed the butcher, had the Christians of the city beheaded as revenge. While fighting in San Juan de Acre, Napoleon deployed different units through Palestine to seize vital points in the region. Junot took Nazareth, but had to abandon it to come to the aid of Klébar, besieged on Mount Tabor. His support was going to be of little use, because both contingents numbered 2,000 men against 25,000 Arabs. For six hours they valiantly endured their offensives. Luckily, when all seemed lost, Napoleon burst in with his cannons and cavalry and resolved the danger in half an hour. He then launched a new attack against San Juan de Acre. He managed to break through the first line of walls, but the second was impassable. In the action General Lannes was about to die. The lack of food and demoralization forced Napoleon to lift the siege after 62 days of siege. The way back to Egypt was very hard, due to lack of water and the continuous harassment of the Arab parties. He had to abandon about thirty of his men in a terminal state. Napoleon arrived in Cairo with 5,000 fewer men. With no chance of receiving supplies and the Syrian campaign having failed, he became convinced that reaching India was impossible.

On the other hand, the situation was deteriorating in Egypt. Unrest among Egyptian farmers grew due to excessive taxes, while the French positions scattered throughout the territory and their communication routes were continually harassed by Mamluk parties. While this was taking place, the Second Coalition was being formed in Europe to attack a France weakened by internal political tensions. Napoleon, seeing that he was not getting any return from the Egyptian campaign and that he was far from the metropolis, feared that he would be left out of a new distribution of power. He decided to return as soon as possible, but when he was studying how to do it, he received the news that Nelson was shelling the French defenses at Abukir. An Ottoman contingent of 15,000 men had landed under the command of Mustafa Pasha, which annihilated General Marmont's battalion. Napoleon sent 300 men to his aid, who suffered the same fate. Feeling trapped and unable to retreat, he ordered all the troops scattered in Egypt to regroup for repatriation. But first it was necessary to recover Abukir. Once the army of Egypt was regrouped, he decided to attack. He placed Lannes's men on the right flank, Kléber in the center, Desaix and Murat on the left, and Davout in reserve. The attack began with artillery fire against the Anglo-Ottoman ships, which he forced to withdraw. Once without naval cover, Napoleon ordered to attack, but what he did not expect was that the Ottoman resistance would defeat the charges of Desaix and Murat. When Napoleon was discussing plans to follow with Desaix, the pasha left his positions with his men and ordered the beheading of every Frenchman they came across, whether alive, dead or wounded. Such a spectacle, instead of causing the expected terror, unleashed the anger of the French, who charged with the bayonet.

They did it in a disorderly way, but their rage led them to overwhelm the Ottoman positions in a merciless war. The Ottoman leader became strong in the last bastion. After heavy fighting, Murat's cavalry managed to take it. Capturing Mustafa Pasha, Murat amputated three of his fingers with a saber blow, warning him that he would cut off "more important parts" if he decapitated his men again. Faced with the impossibility of withdrawing, Napoleon handed over command to Kléber and decided to return to France. He set out with his best generals aboard the frigate Muiron, circumvented the British blockade and reached their destination. Napoleon Bonaparte, returned from the Egyptian campaign and taking advantage of the political weakness of the ruling Executive Directorate in France, carried out a surprising coup with the support of the people and the army (knowing his exploits and capabilities in the different campaigns of the Revolutionary Wars). French), together with some ideologues of the Revolution such as Sieyès. That day the Council of Elders was summoned urgently to discuss an alleged Jacobin conspiracy against the government. The Council agreed to move to Saint-Cloud for security reasons, but the following day Napoleon kidnapped the Assembly with the support of the army. Taking advantage of the intrigues and the division of powers between the legislative and executive apparatuses of the State, and of course resorting to personal coercion, he managed to get the French deputies to name Sieyès, Roger Ducos and himself provisional Consuls, creating what became known as the triumvirate. The constitutional reform was immediately prepared. Measures were taken to ensure the social order in the country, accompanying the economic measures with the exile of the Jacobins, while Bonaparte increased his popularity thanks to these measures and his continuous public appearances, exercising the role of savior of the homeland. . Despite the fact that the Republic theoretically had three consuls, only Napoleon came to exercise it thanks to a legal trick consisting of starting the government of the consuls in alphabetical order (Bonaparte-Ducos-Sieyès).