If Apollo 13 had gone as well as Apollo 11 and 12, that might have been on the cards; I can't see NASA radically altering the profile for a 'Return to Flight' mission. And they needed Apollo 12 as well - Apollo 11 was way off course, and they had to perfect the pinpoint landing before they could start the scientific missions.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

To Slip The Surly Bonds of Earth - Alternate Apollo Program

- Thread starter Methuslah

- Start date

Applied Science At Work (Apollo Applications)

While the visible parts of NASA concentrated on the lunar landings, scheduled for the next three years, another contingent was working on the Apollo Applications Program. Originally, this had been a huge program, designed as the major post-landing follow-on, with lunar bases, huge space stations, even flybys of Mars and Venus! By 1971, all that remained of these missions were two space stations, by Presidential order named the 'Abraham Lincoln' and the 'George Washington'. There was some controversy in these names – many expected the 'John F. Kennedy' to be one of the two stations, but there was no way that Richard Nixon was going to allow that one to happen.

There had been plans to launch the workships 'dry', already completed and ready for occupancy, but this died with the decision to use all of the Saturn V rockets for lunar exploration in 1969. There remained seven Saturn IB rockets and four Apollo CSM, however, and all of these could be made available to the program. This translated as twelve astronaut seats over two stations, with one 'spare' booster.

By 1970, Charles Townes was running the Skylab program; the new administrator had named him in the wake of the emergency Apollo Applications Working Group, and he pushed hard for the stations to focus on a combination of medical science and astronomy. The weight restrictions made this a difficult task, but there remained that last booster, and someone remembered that there was a 'spare', half-completed LEM as well.

The 'Abraham Lincoln' would launch in 1975, for two missions totalling eighty-four days in length. The first crew would remain in orbit for twenty-four days, and their job was to outfit the station, for the follow-up crew, and practice actually working in space. The second crew would focus on biomedical research principally, as well as some Earth Observation.

'George Washington', launched in 1976, would be more ambitious – two missions totalling ninety-six days in length. The first crew, again, would outfit the station, but the station would be equipped with two docking collars rather than one, to allow the launch, in the middle of the first occupancy, of a special instrument package, an optical telescope built using the LEM – this was taken from the cancelled plans for an 'Apollo Telescope Mount'. All things being equal, NASA would have preferred to launch the station in 1977 or 1978, but the opportunity to exploit the Bicentennial was too good to pass up.

As it stood, that would be the 'glorious finale' to America's manned space program, but no-one at NASA wanted that to be so. Quietly, Administrator Low created a 'Future Projects Task Group', under George Mueller and Tom Stafford, whose goal was to create a sustainable manned space program, under a budget similar to that they were receiving in 1972 – already substantially down from its peak in 1968. It was to report in eight months, with the goal of providing options for the President – whether Nixon or a Democrat – to revitalise the space program. Or in the worst-case – close it down.

While the visible parts of NASA concentrated on the lunar landings, scheduled for the next three years, another contingent was working on the Apollo Applications Program. Originally, this had been a huge program, designed as the major post-landing follow-on, with lunar bases, huge space stations, even flybys of Mars and Venus! By 1971, all that remained of these missions were two space stations, by Presidential order named the 'Abraham Lincoln' and the 'George Washington'. There was some controversy in these names – many expected the 'John F. Kennedy' to be one of the two stations, but there was no way that Richard Nixon was going to allow that one to happen.

There had been plans to launch the workships 'dry', already completed and ready for occupancy, but this died with the decision to use all of the Saturn V rockets for lunar exploration in 1969. There remained seven Saturn IB rockets and four Apollo CSM, however, and all of these could be made available to the program. This translated as twelve astronaut seats over two stations, with one 'spare' booster.

By 1970, Charles Townes was running the Skylab program; the new administrator had named him in the wake of the emergency Apollo Applications Working Group, and he pushed hard for the stations to focus on a combination of medical science and astronomy. The weight restrictions made this a difficult task, but there remained that last booster, and someone remembered that there was a 'spare', half-completed LEM as well.

The 'Abraham Lincoln' would launch in 1975, for two missions totalling eighty-four days in length. The first crew would remain in orbit for twenty-four days, and their job was to outfit the station, for the follow-up crew, and practice actually working in space. The second crew would focus on biomedical research principally, as well as some Earth Observation.

'George Washington', launched in 1976, would be more ambitious – two missions totalling ninety-six days in length. The first crew, again, would outfit the station, but the station would be equipped with two docking collars rather than one, to allow the launch, in the middle of the first occupancy, of a special instrument package, an optical telescope built using the LEM – this was taken from the cancelled plans for an 'Apollo Telescope Mount'. All things being equal, NASA would have preferred to launch the station in 1977 or 1978, but the opportunity to exploit the Bicentennial was too good to pass up.

As it stood, that would be the 'glorious finale' to America's manned space program, but no-one at NASA wanted that to be so. Quietly, Administrator Low created a 'Future Projects Task Group', under George Mueller and Tom Stafford, whose goal was to create a sustainable manned space program, under a budget similar to that they were receiving in 1972 – already substantially down from its peak in 1968. It was to report in eight months, with the goal of providing options for the President – whether Nixon or a Democrat – to revitalise the space program. Or in the worst-case – close it down.

Exploration at its Finest (Apollo 16)

In the eyes of many, particularly in the scientific community, the first four landings on the moon had only been the run-up to the remaining five landings – the five 'J' missions designed to maximise the scientific potential of the Apollo landing system. Not only would the 'stay' time on the surface be significantly extended, allowing a third spacewalk, but the 'lunar rover' would be carried to the moon for the first time, greatly expanding the range of action of the astronauts on the moon.

The crew, commanded by John Young with LM pilot Charlie Duke and CSM pilot Jack Swigert, was regarded as a 'safe pair of hands' for this first landing; Swigert was considered one of the most familiar astronauts with the CSM in NASA, and John Young had participated in three successful missions, including the Apollo 10 flight that tested the LM in lunar orbit. This flight would make John Young the first man to leave Earth orbit for the second time.

Many in the Astronaut Corps were far more interested in the next flight than in Apollo 16, however, as the backup crew would almost certainly be the last men to walk on the moon in main-line Apollo as the crew of Apollo 20. Several of the Group V astronauts were yet to be assigned a flight, though it was assumed that those that would not go to the moon would have their chance on Skylab. The prime crew was as expected – Gordo Cooper was getting his Apollo mission, with Joe Engle as LMP and Ron Evans as CMP. The backup crew was more of a surprise.

Some months previously, Deke Slayton had managed to return to active flight status with the clear-up of his heart condition; he was now eligible for a mission. NASA Administrator George Low himself approved Deke Slayton's selection of himself as backup crew commander for Apollo 17, tacitly giving him the final commander's slot. Jack Lousma was a logical choice as CMP, but more than a few eyes were raised when a third scientist-astronaut was named as LMP, Joe Allen. The remaining two Group V astronauts, Weitz and Lind, were told that they were to fly on Skylab 1 and 2 respectively, on flights to take place in 1975.

The launch of Apollo 16 took place on schedule on April 16, 1972, though the landing proved fraught with difficulty when several of the power systems on the Command Module appeared to fail; this problem was solved by a tiger-team headed by Apollo 14 veteran Ken Mattingly in the nick of time, allowing the landing to take place as scheduled at Descartes.

The new systems proved to be everything that was hoped for. The highlight was the discovery of orange soil on the surface of the moon, which at the time was thought to be evidence of lunar volcanism; later examination would reveal that it was actually the aftermath of meteoric impacts, but this was no less as fascinating a find. A series of performance tests with the lunar rover were conducted, and take-off from the moon took place on April 23rd, Apollo 16 returning to Earth on April 28th.

In the eyes of many, particularly in the scientific community, the first four landings on the moon had only been the run-up to the remaining five landings – the five 'J' missions designed to maximise the scientific potential of the Apollo landing system. Not only would the 'stay' time on the surface be significantly extended, allowing a third spacewalk, but the 'lunar rover' would be carried to the moon for the first time, greatly expanding the range of action of the astronauts on the moon.

The crew, commanded by John Young with LM pilot Charlie Duke and CSM pilot Jack Swigert, was regarded as a 'safe pair of hands' for this first landing; Swigert was considered one of the most familiar astronauts with the CSM in NASA, and John Young had participated in three successful missions, including the Apollo 10 flight that tested the LM in lunar orbit. This flight would make John Young the first man to leave Earth orbit for the second time.

Many in the Astronaut Corps were far more interested in the next flight than in Apollo 16, however, as the backup crew would almost certainly be the last men to walk on the moon in main-line Apollo as the crew of Apollo 20. Several of the Group V astronauts were yet to be assigned a flight, though it was assumed that those that would not go to the moon would have their chance on Skylab. The prime crew was as expected – Gordo Cooper was getting his Apollo mission, with Joe Engle as LMP and Ron Evans as CMP. The backup crew was more of a surprise.

Some months previously, Deke Slayton had managed to return to active flight status with the clear-up of his heart condition; he was now eligible for a mission. NASA Administrator George Low himself approved Deke Slayton's selection of himself as backup crew commander for Apollo 17, tacitly giving him the final commander's slot. Jack Lousma was a logical choice as CMP, but more than a few eyes were raised when a third scientist-astronaut was named as LMP, Joe Allen. The remaining two Group V astronauts, Weitz and Lind, were told that they were to fly on Skylab 1 and 2 respectively, on flights to take place in 1975.

The launch of Apollo 16 took place on schedule on April 16, 1972, though the landing proved fraught with difficulty when several of the power systems on the Command Module appeared to fail; this problem was solved by a tiger-team headed by Apollo 14 veteran Ken Mattingly in the nick of time, allowing the landing to take place as scheduled at Descartes.

The new systems proved to be everything that was hoped for. The highlight was the discovery of orange soil on the surface of the moon, which at the time was thought to be evidence of lunar volcanism; later examination would reveal that it was actually the aftermath of meteoric impacts, but this was no less as fascinating a find. A series of performance tests with the lunar rover were conducted, and take-off from the moon took place on April 23rd, Apollo 16 returning to Earth on April 28th.

The Russians are Coming, the Russians are Coming!

The Soviet space program had appeared to stall somewhat after the failure to reach the moon; despite the protests of almost the entire Cosmonaut Corps, the circumlunar flight had not been approved, believed too hazardous, and instead only a few test-flights of the new Soyuz capsule were organised. However, they continued to work.

Korolev's last project initiated before his untimely death – the N1 rocket – was nearing completion,. It proved to be an engineering nightmare, several orders of magnitude more complicated than anything previously built. The first model had launched in 1969, but exploded on launch; the following three models were similar failures, but the designers and engineers were confident that they would eventually perfect the rocket. It's mission, however, was unclear.

Except to the visionaries at the heart of the program. Reaching the moon had always been a secondary goal for the Russians; the first slogan of the original rocketeers had been, “Onward to Mars!”, and the N1 rocket was designed not for a lunar mission, but for the assembly of a spacecraft capable of reaching Mars. A new goal was required for the program; they had failed to reach the moon, but it seemed – just – possible that their original might be possible, though not for some years. No matter; they could take the long view.

The Soviet government were not going to approve a Mars mission. At least, not yet. Fortunately, there were strong military applications inherent in the early stages. Rumours and whispers that the American space stations were to be operated by the USAF proved very interesting, and furthermore – a manned space platform would be an excellent way to outpace the Americans. A new direction, then was imposed – towards orbital space stations, ideally launched by the mammoth N1 booster. These stations could not only work for military reconnaissance, but also provide the needed experience of living in space. Nothing if not ambitious, the engineers agreed, and prepared for one final flight.

Plans for a 'Salyut' space station to be launched by a proven Proton booster were placed on hold; Chief Designer Mishin had one last chance to fire his booster, and the fifth N1 rocket rolled out to the launch pad at Baikonur in early 1973. The launch surpassed the previous records easily, sailing up into the sky – and placed its 'dummy' cargo, a Cosmos satellite designed to relay launch data, into orbit. There had been some problems, but with a successful launch, Mishin's job was secure, and the assembly lines could begin. The first Soviet space platform, Salyut, was to launch in 1974 – a year before the planned launch of the 'Abraham Lincoln'. Larger 'Mir' stations would follow in the later 1970s, launched on improved N1 boosters.

(It would be learned some years later that Mishin had expected the N1 to fail, with almost no confidence in it; hopes were being pinned on the new 'N1F'. It was a throw of the dice, and fortunately a successful one; it would be the N1F that launched Mir 1, a year later than originally planned.)

The Soviet space program had appeared to stall somewhat after the failure to reach the moon; despite the protests of almost the entire Cosmonaut Corps, the circumlunar flight had not been approved, believed too hazardous, and instead only a few test-flights of the new Soyuz capsule were organised. However, they continued to work.

Korolev's last project initiated before his untimely death – the N1 rocket – was nearing completion,. It proved to be an engineering nightmare, several orders of magnitude more complicated than anything previously built. The first model had launched in 1969, but exploded on launch; the following three models were similar failures, but the designers and engineers were confident that they would eventually perfect the rocket. It's mission, however, was unclear.

Except to the visionaries at the heart of the program. Reaching the moon had always been a secondary goal for the Russians; the first slogan of the original rocketeers had been, “Onward to Mars!”, and the N1 rocket was designed not for a lunar mission, but for the assembly of a spacecraft capable of reaching Mars. A new goal was required for the program; they had failed to reach the moon, but it seemed – just – possible that their original might be possible, though not for some years. No matter; they could take the long view.

The Soviet government were not going to approve a Mars mission. At least, not yet. Fortunately, there were strong military applications inherent in the early stages. Rumours and whispers that the American space stations were to be operated by the USAF proved very interesting, and furthermore – a manned space platform would be an excellent way to outpace the Americans. A new direction, then was imposed – towards orbital space stations, ideally launched by the mammoth N1 booster. These stations could not only work for military reconnaissance, but also provide the needed experience of living in space. Nothing if not ambitious, the engineers agreed, and prepared for one final flight.

Plans for a 'Salyut' space station to be launched by a proven Proton booster were placed on hold; Chief Designer Mishin had one last chance to fire his booster, and the fifth N1 rocket rolled out to the launch pad at Baikonur in early 1973. The launch surpassed the previous records easily, sailing up into the sky – and placed its 'dummy' cargo, a Cosmos satellite designed to relay launch data, into orbit. There had been some problems, but with a successful launch, Mishin's job was secure, and the assembly lines could begin. The first Soviet space platform, Salyut, was to launch in 1974 – a year before the planned launch of the 'Abraham Lincoln'. Larger 'Mir' stations would follow in the later 1970s, launched on improved N1 boosters.

(It would be learned some years later that Mishin had expected the N1 to fail, with almost no confidence in it; hopes were being pinned on the new 'N1F'. It was a throw of the dice, and fortunately a successful one; it would be the N1F that launched Mir 1, a year later than originally planned.)

Last edited:

The Soviet space program had appeared to stall somewhat after the failure to reach the moon; despite the protests of almost the entire Cosmonaut Corps, the circumlunar flight had not been approved, believed too hazardous, and instead only a few test-flights of the new Soyuz capsule were organised. However, they continued to work.

Korolev's last project initiated before his untimely death – the N1 rocket – was nearing completion,. It proved to be an engineering nightmare, several orders of magnitude more complicated than anything previously built. The first model had launched in 1969, but exploded on launch; the following three models were similar failures, but the designers and engineers were confident that they would eventually perfect the rocket. It's mission, however, was unclear.

Except to the visionaries at the heart of the program. Reaching the moon had always been a secondary goal for the Russians; the first slogan of the original rocketeers had been, “Onward to Mars!”, and the N1 rocket was designed not for a lunar mission, but for the assembly of a spacecraft capable of reaching Mars. A new goal was required for the program; they had failed to reach the moon, but it seemed – just – possible that their original might be possible, though not for some years. No matter; they could take the long view.

The Soviet government were not going to approve a Mars mission. At least, not yet. Fortunately, there were strong military applications inherent in the early stages. Rumours and whispers that the American space stations were to be operated by the USAF proved very interesting, and furthermore – a manned space platform would be an excellent way to outpace the Americans. A new direction, then was imposed – towards orbital space stations, ideally launched by the mammoth N1 booster. These stations could not only work for military reconnaissance, but also provide the needed experience of living in space. Nothing if not ambitious, the engineers agreed, and prepared for one final flight.

Plans for a 'Salyut' space station to be launched by a proven Proton booster were placed on hold; Chief Designer Mishin had one last chance to fire his booster, and the fifth N1 rocket rolled out to the launch pad at Baikonur in early 1972. The launch surpassed the previous records easily, sailing up into the sky – and placed its 'dummy' cargo, a Cosmos satellite designed to relay launch data, into orbit. There had been some problems, but with a successful launch, Mishin's job was secure, and the assembly lines could begin. The first Soviet space platform, Salyut, was to launch in 1974 – a year before the planned launch of the 'Abraham Lincoln'. Larger 'Mir' stations would follow in the later 1970s, launched on improved N1 boosters.

(It would be learned some years later that Mishin had expected the N1 to fail, with almost no confidence in it; hopes were being pinned on the new 'N1F'. It was a throw of the dice, and fortunately a successful one; it would be the N1F that launched Mir 1, a year later than originally planned.)

One small problem with your timeline. The N1's fourth and final test flight IOTL occured in the fourth quarter of 1972, so a fifth flight could not occur until at least 1973.

That said, it's nice to see that the N1 has a chance to be used for it's original purpose, single-launch 80+ Tonne space stations and Mars missions via EOR. It was, after all, the push for the Moon, with the need to substantially upgrade the payload limit that proved to be a major factor in it's initially appaling reliability rating. And with the N1F - with the new, robust, reliable NK-33, NK-43 and NK-39 engines - almost certain to see use, we might see a plausible 'if only' scenario for it.

One small problem with your timeline. The N1's fourth and final test flight IOTL occured in the fourth quarter of 1972, so a fifth flight could not occur until at least 1973.

That said, it's nice to see that the N1 has a chance to be used for it's original purpose, single-launch 80+ Tonne space stations and Mars missions via EOR. It was, after all, the push for the Moon, with the need to substantially upgrade the payload limit that proved to be a major factor in it's initially appaling reliability rating. And with the N1F - with the new, robust, reliable NK-33, NK-43 and NK-39 engines - almost certain to see use, we might see a plausible 'if only' scenario for it.

Edited to '1973' - it doesn't affect the timeline a jot. With no expensive Orbiter program, then the Russians can do a lot more with the resources they've got. I've been beginning to think about the post-'77 timeline now, how to push this past the last main-line Apollo mission.

Dan Reilly The Great

Banned

Edited to '1973' - it doesn't affect the timeline a jot. With no expensive Orbiter program, then the Russians can do a lot more with the resources they've got. I've been beginning to think about the post-'77 timeline now, how to push this past the last main-line Apollo mission.

~cough~seadragon~cough~

The crew, commanded by John Young with LM pilot Charlie Duke and CSM pilot Jack Swigert, was regarded as a 'safe pair of hands' for this first landing; Swigert was considered one of the most familiar astronauts with the CSM in NASA, and John Young had participated in three successful missions, including the Apollo 10 flight that tested the LM in lunar orbit. This flight would make John Young the first man to leave Earth orbit for the second time.

Not Jim Lovell? Apollo 8 orbited the Moon, and of course in this TL he commanded Apollo 14.

Wondering if this thread will be re-started soon. It's been idle for a while now, though not enough to be considered dead at the moment.

A long time lurker here - I was wondering if this thread would be resurrected. Of course - it's not the first thread on this topic that's been vetted around here.

It's an intriguing "what if" in view of the unfulfilled promises of the shuttle program - which turned out to be far more expensive, risky and difficult to operate than was projected by NASA in the early 1970's when the program was first approved. The apparent return to expendable rockets seems to confirm the wisdom of continuing Apollo/Saturn in some form, albeit at a reduced tempo given the budget realities NASA faced in the 70's.

A glimpse at what was lost can be read in Thomas Frieling's Quest article, "Skylab B: Unflown Missions, Lost Opportunities." Frieling's article is profoundly sympathetic to NASA's plight as it considered every possible option for using its second Skylab station and its other remaining Saturn/Apollo hardware (two Saturn V launchers, two essentially complete Saturn 1b's, and at least 3 largely complete CSM's and two partially complete LM's). The realities of shuttle development costs, which were quickly absorbing the bulk of NASA's budget, precluded the use of this hardware without additional funding, which was not forthcoming. Put simply: NASA could not continue Apollo Applications and develop the shuttle at the same time. One had to go. NASA chose the shuttle, and not for irrational reasons - the shuttle's promise of economical reusability seemed like an easier sell to a skeptical Congress.

Link to article pdf: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&sour...89GjDQ&usg=AFQjCNHSTijW0s8gaG9KyFyg-mazZmiSYw

All of which is especially frustrating when you consider that the International Space Station - now essentially complete - has taken 40 launches (employing the NASA shuttles and Russian Proton rockets) to assemble the 417,000kg of the station mass. Yet it would have taken only four Saturn V launches to lift the same mass to LEO. (The configuration of the station would have to significantly change, of course; but the point is a comparison of payload capability of the STS versus Saturn V).

A few points, and then perhaps a tentative new ATL:

1) Methuslah's premise is this: "The idea here is that NASA is to use all the hardware currently in inventory up. (That and complete the last two LM, and finish CSM-115a). No new development is to take place other than modifications of the hardware currently in the inventory." This makes it a more likely premise to work with in the short term, but also one that leaves enormous unanswered questions about NASA's future after that hardware is used up - and new hardware requires lots of lead time. I think the premise has to consider what NASA would attempt, long-term, if the shuttle were DOA.

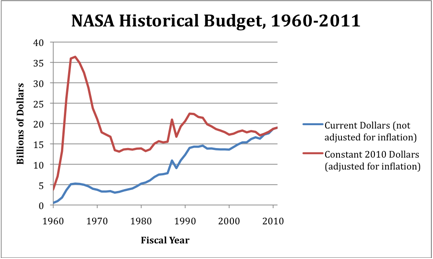

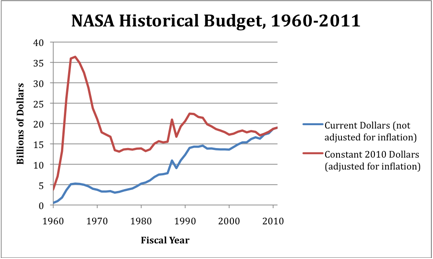

The two commonly discussed limiting factors in that equation are 1) NASA's declining budgets, which peaked in 1965 at about $34 billion in 2007 dollars, and then began a steady slide to about one third that by 1974 - all reflecting reduced public support for NASA; and 2) the skepticism and limited political capital of the new Nixon Administration, which was by most accounts less supportive of NASA and the moon missions than the Johnson and Kennedy Administrations had been. This second point is hotly debated, of course, as we have seen on this thread. Nixon was not in fact as irrationally opposed to NASA for personal reasons as is often suggested - he could see the public relations value of the thing as well as anyone - but it was a noticeably lower priority, as evidenced by his willingness to consider cancelling even Apollo 16 and 17 before Caspar Weinberger talked him out of it. Still, Nixon did keep sufficient funding to complete the bulk of the H and J missions, and did in the end approve the shuttle program. The larger factor may be his reduced capital before a strongly Democratic Congress, even well before Watergate. It would be an interesting variant on this ATL is if we elect a Democrat in 1968 (Johnson, Kennedy or even McCarthy) - they would have greater commitment and greater capital, most likely, which might result in at least a modest reduction in NASA's budget cuts. I might discuss that later if there is any interest.

2) What might be possible with existing budgets, then, if we assume the shuttle is scuttled and NASA invests instead in continuing Apollo Saturn at a reduced tempo? Consider the basic costs involved:

Titan IIID Flyaway cost: $52.2million (1965 dollars)

Saturn 1B Flyaway cost: $55 million (1972 dollars)

Saturn V Flyaway cost $185 million (1969 dollars) - 1.11 billion in 2011 dollars

Cost of Apollo moon mission - $350 million (H mission) -$450 million (J mission)

Even at NASA's reduced 1970s' funding levels (about $3.5 billion in nominal dollars), the 60% or so available for manned flight could, as we can see, support at least a reduced tempo Apollo Applications schedule -at least one Saturn V flight (devoted to either a moon mission or lifting a Skylab "dry workshop" station), and possibly even a couple of Saturn 1b LEO flights to a space station. I say "Saturn 1b" because, as noted above, it wasn't that much more expensive than a Titan III and it was at least man rated.

So NASA would have to buy more rockets and more manned hardware after the existing hardware was used. The good news is that the (canceled) second production run of Saturn Vs would very likely have used the F-1A engine in its first stage, providing a substantial performance boost, and possibly a stretched S-IC first stage to support the more powerful F-1As; and uprated J-2s for the upper stages. This matters because it makes more readily possible more ambitious LEO construction or extended moon missions, such as were planned for the Apollo Extension Systems (AES) and Lunar Exploration System for Apollo (LESA). It is also true that alternate Saturn vehicles were considered (as others, like Truth Is Life, have noted here and on previous threads), such as Saturn INT-20 or a Saturn II, providing an intermediate heavy lift capability. But that would have required significant development costs, so I set that aside for longer term development, say for the early 1980's.

So let us consider a possible timeline that works on these assumptions - Nixon approves another limited buy of Saturn rockets in the FY 1970 budget, say five new Saturn V's and a few more Saturn 1b's, and the other requisite hardware, costs to be spread out over the next several years:

One other addition: A dedicated Saturn 1b/Modified CSM for Skylab Rescue, kept available for both space station schedules.

The schedule for each fiscal year after FY 1972 is fairly modest: no more than two (2) Saturn V lunar launches or one (1) Saturn V lofted space station paired with three manned Saturn 1B LEO station crews. Of course the hardware required for the later AES missions would have entailed significant development costs, but not unreasonable ones, since much of the design work had already been done for the extended LM, the Block III CSM, and even the LEM Shelter. A special orbital module would be needed for the 30 day LOSM mission in 1974, but would be easier and cheaper to manage than the LM, since it did not have to land or takeoff. All of this would be quite achievable under NASA budgets as they existed in the 1970's - if you take the shuttle out of the equation. It leverages existing hardware and facilities to the greatest degree possible.

Partnering with ESA, as was considered at one point, also makes the second Skylab "b" station more attractive to the Nixon and Ford administration(s) and Congress, not least because ESA could kick in funding - and no one would be keen on disappointing the Europeans once development had proceeded. Which is precisely how Clinton was able to salvage the ISS in the 1990's.

Spacelab (Skylab B) would finish this initial schedule and take us into the Carter Administration. The requisition of a larger second Saturn V and Saturn 1B buy could help lock in a continued program along these lines - but as we have seen in our history OTL, there is no guarantee. Harder choices might have to be made - an upgraded Skylab for extended life would require regular crew visits and even expansion, building in a permanent flight schedule every year, while the next planned lunar exploration phase, LESA, required a two launch profile with much more ambitious hardware and much longer stays - 90 to 180 days. And that would also cost more money. And run the risk of having to run such missions at the same time as LEO Skylab missions. Perhaps NASA could not do both with existing funding levels.

My guess is that NASA at that point would find sticking to LEO for the time being an easier sell - less risky, less cost. And after all, if NASA maintains the Saturn and Apollo hardware lines, they will still be there once it is able to return to the Moon, if it so desires - perhaps later in the 1980's, when the technology expands mission possibilities and safety. Every moonshot heavily leveraged existing (primitive) technology, and most ran into at least one potential mission-ending incident that NASA managed to finesse, without any possibility of rescue. NASA got very lucky with Apollo 13 - imagine the reaction if the Apollo 19 LOSM is unable to fire its SPS engine, leaving the astronauts to die in lunar orbit...or any of a hundred other scenarios that results in dead astronauts in deep space. A stranded crew in LEO at least would have had a chance at rescue.

Of course, if any of the succeeding moon missions (Apollo 20-23) do find something worthwhile on the lunar surface - water for in situ uses, and Helium 3 for mining - that could change the calculus considerably.

* * *

The more I think about it, an aggressive focus on space station work in LEO might have been a safer bet than an extended lunar program. Lunar exploration with 1960's technology was tremendously risky, and the payoff - mainly exploration of lunar geology (selenology) could not really justify the risk, let alone the cost. A modular "American Mir" station using the last Saturn V (or two, if you drop Apollo 18 as in OTL), and a new series of Saturn II's or INT-20's (on the assumption that these will be easier to sell to Congress than resumed Saturn V production) beginning in the late 1970's, serviced by Block III CSM's, would still be advantageous over what STS gave us.

And resumed lunar exploration, if desired, could be resumed in the 80's or 90's once technology and resources made it a less risky proposition.

* * *

Budget Appendices:

It's an intriguing "what if" in view of the unfulfilled promises of the shuttle program - which turned out to be far more expensive, risky and difficult to operate than was projected by NASA in the early 1970's when the program was first approved. The apparent return to expendable rockets seems to confirm the wisdom of continuing Apollo/Saturn in some form, albeit at a reduced tempo given the budget realities NASA faced in the 70's.

A glimpse at what was lost can be read in Thomas Frieling's Quest article, "Skylab B: Unflown Missions, Lost Opportunities." Frieling's article is profoundly sympathetic to NASA's plight as it considered every possible option for using its second Skylab station and its other remaining Saturn/Apollo hardware (two Saturn V launchers, two essentially complete Saturn 1b's, and at least 3 largely complete CSM's and two partially complete LM's). The realities of shuttle development costs, which were quickly absorbing the bulk of NASA's budget, precluded the use of this hardware without additional funding, which was not forthcoming. Put simply: NASA could not continue Apollo Applications and develop the shuttle at the same time. One had to go. NASA chose the shuttle, and not for irrational reasons - the shuttle's promise of economical reusability seemed like an easier sell to a skeptical Congress.

Link to article pdf: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&sour...89GjDQ&usg=AFQjCNHSTijW0s8gaG9KyFyg-mazZmiSYw

All of which is especially frustrating when you consider that the International Space Station - now essentially complete - has taken 40 launches (employing the NASA shuttles and Russian Proton rockets) to assemble the 417,000kg of the station mass. Yet it would have taken only four Saturn V launches to lift the same mass to LEO. (The configuration of the station would have to significantly change, of course; but the point is a comparison of payload capability of the STS versus Saturn V).

A few points, and then perhaps a tentative new ATL:

1) Methuslah's premise is this: "The idea here is that NASA is to use all the hardware currently in inventory up. (That and complete the last two LM, and finish CSM-115a). No new development is to take place other than modifications of the hardware currently in the inventory." This makes it a more likely premise to work with in the short term, but also one that leaves enormous unanswered questions about NASA's future after that hardware is used up - and new hardware requires lots of lead time. I think the premise has to consider what NASA would attempt, long-term, if the shuttle were DOA.

The two commonly discussed limiting factors in that equation are 1) NASA's declining budgets, which peaked in 1965 at about $34 billion in 2007 dollars, and then began a steady slide to about one third that by 1974 - all reflecting reduced public support for NASA; and 2) the skepticism and limited political capital of the new Nixon Administration, which was by most accounts less supportive of NASA and the moon missions than the Johnson and Kennedy Administrations had been. This second point is hotly debated, of course, as we have seen on this thread. Nixon was not in fact as irrationally opposed to NASA for personal reasons as is often suggested - he could see the public relations value of the thing as well as anyone - but it was a noticeably lower priority, as evidenced by his willingness to consider cancelling even Apollo 16 and 17 before Caspar Weinberger talked him out of it. Still, Nixon did keep sufficient funding to complete the bulk of the H and J missions, and did in the end approve the shuttle program. The larger factor may be his reduced capital before a strongly Democratic Congress, even well before Watergate. It would be an interesting variant on this ATL is if we elect a Democrat in 1968 (Johnson, Kennedy or even McCarthy) - they would have greater commitment and greater capital, most likely, which might result in at least a modest reduction in NASA's budget cuts. I might discuss that later if there is any interest.

2) What might be possible with existing budgets, then, if we assume the shuttle is scuttled and NASA invests instead in continuing Apollo Saturn at a reduced tempo? Consider the basic costs involved:

Titan IIID Flyaway cost: $52.2million (1965 dollars)

Saturn 1B Flyaway cost: $55 million (1972 dollars)

Saturn V Flyaway cost $185 million (1969 dollars) - 1.11 billion in 2011 dollars

Cost of Apollo moon mission - $350 million (H mission) -$450 million (J mission)

Even at NASA's reduced 1970s' funding levels (about $3.5 billion in nominal dollars), the 60% or so available for manned flight could, as we can see, support at least a reduced tempo Apollo Applications schedule -at least one Saturn V flight (devoted to either a moon mission or lifting a Skylab "dry workshop" station), and possibly even a couple of Saturn 1b LEO flights to a space station. I say "Saturn 1b" because, as noted above, it wasn't that much more expensive than a Titan III and it was at least man rated.

So NASA would have to buy more rockets and more manned hardware after the existing hardware was used. The good news is that the (canceled) second production run of Saturn Vs would very likely have used the F-1A engine in its first stage, providing a substantial performance boost, and possibly a stretched S-IC first stage to support the more powerful F-1As; and uprated J-2s for the upper stages. This matters because it makes more readily possible more ambitious LEO construction or extended moon missions, such as were planned for the Apollo Extension Systems (AES) and Lunar Exploration System for Apollo (LESA). It is also true that alternate Saturn vehicles were considered (as others, like Truth Is Life, have noted here and on previous threads), such as Saturn INT-20 or a Saturn II, providing an intermediate heavy lift capability. But that would have required significant development costs, so I set that aside for longer term development, say for the early 1980's.

So let us consider a possible timeline that works on these assumptions - Nixon approves another limited buy of Saturn rockets in the FY 1970 budget, say five new Saturn V's and a few more Saturn 1b's, and the other requisite hardware, costs to be spread out over the next several years:

Code:

Apollo 7 C Manned CSM evaluation in low Earth orbit Oct. 1968 Sat Ib 11 day

Apollo 8 "C Prime" Manned CSM only operation in lunar orbit Dec. 1968 Sat V 8 day

Apollo 9 D Manned CSM and LM development in low Earth orbit March 1969 Sat V 10 day

Apollo 10 F Manned CSM and LM operations in lunar orbit May 1969 Sat V 8 day

Apollo 11 G First Manned landing on Moon July 1969 Sat V 9 day/1 day

Apollo 12 H Precision landings with up to two-day stays on the Moon Nov. 1969 Sat V 10 day/1 day

Apollo 13 H Precision landings (Mission aborted) Apr. 1970 Sat V 5 day

Apollo 14 H Precision landings with up to two-day stays on the Moon Jan. 1971 Sat V 9 day/1 day

Apollo 15 J Longer three-day stays using Extended LM, rover July 1971 Sat V 12 day/3 day

Apollo 16 J Longer three-day stays using Extended LM, rover Apr. 1972 Sat V 12 day/3 day

Apollo 17 J Longer three-day stays using Extended LM, rover Dec. 1972 Sat V 12 day/3 day

Apollo 18 J Longer three-day stays using Extended LM, rover Apr. 1973 Sat V 12 day/3 day

Skylab 1 - Unmanned launch of Skylab station July 1973 Sat V -

Skylab 2 SS1 28 day scientific mission in Skylab station July 1973 Sat 1b 28 day

Skylab 3 SS1 59 day scientific mission in Skylab station Sept 1973 Sat 1b 59 day

Skylab 4 SS1 84 day scientific mission in Skylab station Jan. 1974 Sat 1b 84 day

Apollo 19 LOSM Lunar Orbit Survey Mission using lunar orbital module Oct. 1974 Sat V 28 day

Apollo-Soyuz Joint US-Soviet LEO scientific mission using ASTP dock July 1975 Sat 1b 9 day

*Apollo 20 AES 1 Delivery of LEM Shelter to Moon for Apollo 21, Oct. 1975 Sat V"b" 11 day

*Apollo 21 AES 2 14 Day stay using LEM Shelter, Extended CSM, rover Nov. 1975 Sat V"b" 32 day/14 day

*Apollo 22 AES 1 Delivery of LEM Shelter to Moon for Apollo 23, Oct. 1976 Sat V"b" 11 day

*Apollo 23 AES 2 14 Day stay using LEM Shelter, Extended CSM, rover Nov. 1976 Sat V"b" 33 day/15 day

*Spacelab 1 Unmanned launch of long duration Spacelab (Skylab B) Dec. 1977 Sat V"b" -

Spacelab 2 Long duration International expedition in Spacelab Jan. 1978 Sat. 1b 100 day

Spacelab 3 Long duration international expedition in Spacelab April 1978 Sat. 1b 100 day

*Spacelab 4 Long duration international expedition in Spacelab July 1978 Sat. 1b 120 day

* Requires new hardware buysOne other addition: A dedicated Saturn 1b/Modified CSM for Skylab Rescue, kept available for both space station schedules.

The schedule for each fiscal year after FY 1972 is fairly modest: no more than two (2) Saturn V lunar launches or one (1) Saturn V lofted space station paired with three manned Saturn 1B LEO station crews. Of course the hardware required for the later AES missions would have entailed significant development costs, but not unreasonable ones, since much of the design work had already been done for the extended LM, the Block III CSM, and even the LEM Shelter. A special orbital module would be needed for the 30 day LOSM mission in 1974, but would be easier and cheaper to manage than the LM, since it did not have to land or takeoff. All of this would be quite achievable under NASA budgets as they existed in the 1970's - if you take the shuttle out of the equation. It leverages existing hardware and facilities to the greatest degree possible.

Partnering with ESA, as was considered at one point, also makes the second Skylab "b" station more attractive to the Nixon and Ford administration(s) and Congress, not least because ESA could kick in funding - and no one would be keen on disappointing the Europeans once development had proceeded. Which is precisely how Clinton was able to salvage the ISS in the 1990's.

Spacelab (Skylab B) would finish this initial schedule and take us into the Carter Administration. The requisition of a larger second Saturn V and Saturn 1B buy could help lock in a continued program along these lines - but as we have seen in our history OTL, there is no guarantee. Harder choices might have to be made - an upgraded Skylab for extended life would require regular crew visits and even expansion, building in a permanent flight schedule every year, while the next planned lunar exploration phase, LESA, required a two launch profile with much more ambitious hardware and much longer stays - 90 to 180 days. And that would also cost more money. And run the risk of having to run such missions at the same time as LEO Skylab missions. Perhaps NASA could not do both with existing funding levels.

My guess is that NASA at that point would find sticking to LEO for the time being an easier sell - less risky, less cost. And after all, if NASA maintains the Saturn and Apollo hardware lines, they will still be there once it is able to return to the Moon, if it so desires - perhaps later in the 1980's, when the technology expands mission possibilities and safety. Every moonshot heavily leveraged existing (primitive) technology, and most ran into at least one potential mission-ending incident that NASA managed to finesse, without any possibility of rescue. NASA got very lucky with Apollo 13 - imagine the reaction if the Apollo 19 LOSM is unable to fire its SPS engine, leaving the astronauts to die in lunar orbit...or any of a hundred other scenarios that results in dead astronauts in deep space. A stranded crew in LEO at least would have had a chance at rescue.

Of course, if any of the succeeding moon missions (Apollo 20-23) do find something worthwhile on the lunar surface - water for in situ uses, and Helium 3 for mining - that could change the calculus considerably.

* * *

The more I think about it, an aggressive focus on space station work in LEO might have been a safer bet than an extended lunar program. Lunar exploration with 1960's technology was tremendously risky, and the payoff - mainly exploration of lunar geology (selenology) could not really justify the risk, let alone the cost. A modular "American Mir" station using the last Saturn V (or two, if you drop Apollo 18 as in OTL), and a new series of Saturn II's or INT-20's (on the assumption that these will be easier to sell to Congress than resumed Saturn V production) beginning in the late 1970's, serviced by Block III CSM's, would still be advantageous over what STS gave us.

And resumed lunar exploration, if desired, could be resumed in the 80's or 90's once technology and resources made it a less risky proposition.

* * *

Budget Appendices:

Last edited:

Good work Athelstane !

about "Requires new hardware buys"

next to Saturn V SA-501 to SA-515

was also SA-516 and SA-517 almost complet in 1968, need engines

until the order came "stop assembly, scrap them" because of budget cuts

also canceld was second production run of Saturn V SA-518 to SA-526.

After Document about J-2S Engine

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19690073042_1969073042.pdf

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19690072871_1969072871.pdf

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19790073024_1979073024.pdf

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19740079519_1974079519.pdf

from the SA-518 had advance J-2S, wat had cost-saving in build and Launching

how the F-1A had reduce the Cost i don't know

according Boeing in same papers and in "Saturn Mission Payload Versatility"

to found here http://www.up-ship.com/drawndoc/drawndocspacesaturn.htm

is production of 3 Saturn V per year the optium for production cost

with production run of 30 standart Saturn V from 1968 to 1978

would drop Saturn V Flyaway cost from $185 million to $92 Million

about Skylab, NASA consider in 1971 for a short time

to launch consecutively Five Skylab Station in Orbit

about "Requires new hardware buys"

next to Saturn V SA-501 to SA-515

was also SA-516 and SA-517 almost complet in 1968, need engines

until the order came "stop assembly, scrap them" because of budget cuts

also canceld was second production run of Saturn V SA-518 to SA-526.

After Document about J-2S Engine

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19690073042_1969073042.pdf

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19690072871_1969072871.pdf

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19790073024_1979073024.pdf

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19740079519_1974079519.pdf

from the SA-518 had advance J-2S, wat had cost-saving in build and Launching

how the F-1A had reduce the Cost i don't know

according Boeing in same papers and in "Saturn Mission Payload Versatility"

to found here http://www.up-ship.com/drawndoc/drawndocspacesaturn.htm

is production of 3 Saturn V per year the optium for production cost

with production run of 30 standart Saturn V from 1968 to 1978

would drop Saturn V Flyaway cost from $185 million to $92 Million

about Skylab, NASA consider in 1971 for a short time

to launch consecutively Five Skylab Station in Orbit

Hyperion

Banned

Even if the Russians aren't interested in getting to the Moon anytime soon, in a year or so down the timeline, might they send a mission or two to test equipment or build experience in preparation for a far off Mars mission?

I would think that if the Russians are going to jumpstart space stations in a much bigger way, and not have as much problems down the road with their budget, this could see NASA getting the boost to support Skylab B.

I would think that if the Russians are going to jumpstart space stations in a much bigger way, and not have as much problems down the road with their budget, this could see NASA getting the boost to support Skylab B.

Archibald

Banned

An excellent analysis, really.

Writting my own alt-histories I faced similar dilema.

Continue the lunar landings

or

retreat to LEO (without the shuttle > capsule + space station)

??

Option 1 (continuing lunar landings) resulted in the brief alt-history linked as my signature.

However this is not my favorite space ATL, for the very reasons you mention below (how did you managed to read my mind ??!!)

BINGO !!!

So I developed a second, much longer and detailed space ATL dealing with the above. Apollo is too risky, let's return to LEO for some decades (until 2000) until technology mature.

It takes 10 years to develop a space station (1970 to 1980) then the said space station has a useful life of 15 years (like Mir).

That bring us to 1995, except that every space station has a twin or backup, build for failure, launched later. So that's perhaps 15 more years, up to... 2010. Of course as of 1995 one can use Mir instead of launching the backup space station...

Writting my own alt-histories I faced similar dilema.

Continue the lunar landings

or

retreat to LEO (without the shuttle > capsule + space station)

??

Option 1 (continuing lunar landings) resulted in the brief alt-history linked as my signature.

However this is not my favorite space ATL, for the very reasons you mention below (how did you managed to read my mind ??!!)

The more I think about it, an aggressive focus on space station work in LEO might have been a safer bet than an extended lunar program. Lunar exploration with 1960's technology was tremendously risky, and the payoff - mainly exploration of lunar geology (selenology) could not really justify the risk, let alone the cost. A modular "American Mir" station using the last Saturn V (or two, if you drop Apollo 18 as in OTL), and a new series of Saturn II's or INT-20's (on the assumption that these will be easier to sell to Congress than resumed Saturn V production) beginning in the late 1970's, serviced by Block III CSM's, would still be advantageous over what STS gave us.

And resumed lunar exploration, if desired, could be resumed in the 80's or 90's once technology and resources made it a less risky proposition.

BINGO !!!

So I developed a second, much longer and detailed space ATL dealing with the above. Apollo is too risky, let's return to LEO for some decades (until 2000) until technology mature.

It takes 10 years to develop a space station (1970 to 1980) then the said space station has a useful life of 15 years (like Mir).

That bring us to 1995, except that every space station has a twin or backup, build for failure, launched later. So that's perhaps 15 more years, up to... 2010. Of course as of 1995 one can use Mir instead of launching the backup space station...

the_lyniezian

Banned

I agree that something is going to happen, but politically there are problems ahead. The NASA Administrator submits a totally blue-sky proposal - instead of Nixon eventually agreeing to Shuttle, he just tells them to use up what they've got. Everyone concerned figures that the next term will be different, that Administrator Low can propose something more reasonable as a follow-up program (likely something similar to the Soviet Union, making the Skylab project look a lot more like the Salyut project - whether serviced by a Block III Apollo, Big Gemini, or something new.)

Then Watergate hits. Nixon isn't going to get anything like this through then. The whole mess is going to get dumped on Gerald Ford's lap.

So it is 1974. Manned Space is going to end in 1976, as things stand. What's he going to do?

Except weren't the circumstances that lead to Watergate something of a chance discovery (which could easily be butterflied away)?

Good work Athelstane !

about "Requires new hardware buys"

next to Saturn V SA-501 to SA-515

was also SA-516 and SA-517 almost complet in 1968, need engines

until the order came "stop assembly, scrap them" because of budget cuts

also canceld was second production run of Saturn V SA-518 to SA-526.

After Document about J-2S Engine

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19690073042_1969073042.pdf

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19690072871_1969072871.pdf

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19790073024_1979073024.pdf

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19740079519_1974079519.pdf

from the SA-518 had advance J-2S, wat had cost-saving in build and Launching

how the F-1A had reduce the Cost i don't know

according Boeing in same papers and in "Saturn Mission Payload Versatility"

to found here http://www.up-ship.com/drawndoc/drawndocspacesaturn.htm

is production of 3 Saturn V per year the optium for production cost

with production run of 30 standart Saturn V from 1968 to 1978

would drop Saturn V Flyaway cost from $185 million to $92 Million

about Skylab, NASA consider in 1971 for a short time

to launch consecutively Five Skylab Station in Orbit

Hi Michel,

1. That's a good point about SA-516 and 517. I knew they existed in that incomplete stage; but I wanted to "worst-case" the costs, and assume that little money would be saved by completing them, or that they might be deemed a dead loss after sitting in the warehouse. I just wanted to demonstrate how viable this program could have been, even under less favorable assumptions.

But certainly that gives you two more Saturn V's. And you could upgrade to the new engines with them if you like. In my ATL schedule, that gets you all the way through the first Apollo Extensions System (AES) two-launch mission(s) in late 1975, at the least, once you use up the completed Saturn Vs. If you drop Apollo 18, then you could even free up one more for Skylab B/Spacelab. That helps a fair bit.

2. You also make a good point on the flyaway cost dropoff with a three Saturn V rocket production per year. Of course, that's still about a half billion bucks in current dollars, times three...I am not sure if that would have been feasible with an annual budget creeping down to $3.5 billion (nominal dollars) or less. About 40% of the NASA budget was dedicated to non-manned exploration and research as it was. Then again, considering what it costs to launch the shuttle (which is almost rebuilt after each launch anyway)...at any rate, it may be wise to assume that those projections were somewhat optimistic, especially if you factor in inflation and planned upgrades for the next run. Even so, you are correct in illustrating the possibilities here - possibilities that were cast away.

The question is what you'd do with three Saturn V's per year. That's a lot of lift capability and there are not many missions that would require it. Since we assume that Mars and Venus are unlikely to be approved, that really means lunar missions or LEO station construction. Hmmm...what a station you could have with 30 Saturn V's...

I tend to doubt that Nixon or Congress would have ante'd up for a 30 Saturn V buy, even stretched out over several fiscal years; if nothing else the "optics" of continuing to buy such monsters was unfavorable in that environment. But a smaller buy was certainly possible once shuttle is removed from the picture.

Hello Hyperion,

The Cold War competition aspect makes the whole dynamic much more interesting. Indeed, even once the dynamic reversed, it was Nixon's investment in detente that helped make it possible for NASA to sell him on ASTP (Apollo Soyuz).

But it raises intriguing questions:

1) What if the Soviets soldier on with their lunar program until they get a landing? What if they continue the program with follow up landings? Even in the detente era, that *might* have altered the skepticism toward Apollo on Capitol Hill.

2) What if NASA continues with the lunar components of Apollo Applications, as I suggest in my ATL above? It was easy for the Soviets to beg off the moon race once it was apparent that NASA was only planning a handful of lunar landings with no follow-up; it looked like a publicity stunt. But if NASA is doing more extended missions, the perception might emerge that they're moving toward a lunar base - and that might make the Kremlin interested in putting new vigor into their own foundering moon program.

And once they do, that might make NASA's selling job easier as well.

The Cold War competition aspect makes the whole dynamic much more interesting. Indeed, even once the dynamic reversed, it was Nixon's investment in detente that helped make it possible for NASA to sell him on ASTP (Apollo Soyuz).

But it raises intriguing questions:

1) What if the Soviets soldier on with their lunar program until they get a landing? What if they continue the program with follow up landings? Even in the detente era, that *might* have altered the skepticism toward Apollo on Capitol Hill.

2) What if NASA continues with the lunar components of Apollo Applications, as I suggest in my ATL above? It was easy for the Soviets to beg off the moon race once it was apparent that NASA was only planning a handful of lunar landings with no follow-up; it looked like a publicity stunt. But if NASA is doing more extended missions, the perception might emerge that they're moving toward a lunar base - and that might make the Kremlin interested in putting new vigor into their own foundering moon program.

And once they do, that might make NASA's selling job easier as well.

HellO Archibald,

Thanks for the kind words.

Reading back again through your linked thread, your Option 1 - focus on the moon rather than LEO - I do agree that the LLV used by LESA was a better approach than the AES/ALSS setup. It makes maximum use of the trans-lunar payload capability of the Saturn V. Why send a crew all the way to the moon - with all the risk and cost entailed - just to ferry a LEM shelter to the surface? Well, the answer was, in large part, conservative engineering - NASA was less confident in its ability to remotely pilot the LLV to the lunar surface all the way from Earth. But that attitude might change as NASA became more confident in its systems.

I went with AES missions in the mid-1970's in my ATL simply because it was a smaller leap, easier to sell, more conservative...and it was the progression NASA was looking at in 1968 before moving to LESA. But it is quite possible that as confidence built with Apollo successes, and remote piloting technology matured, NASA might have changed its mind and skipped AES after all.

But that's details when we consider the larger policy question:

As I said, this approach has a lot to be said for it. Going to the Moon is risky. In 1968-1972, it was almost insanely risky. We bent every spar and hoisted every sail, as Jack Aubrey might say, to manage what we did, piloting a CSM a half million miles through space with a 48K RAM main computer. That was a less risk averse environment back then - you could not get away with that stuff now - but it was moving in a more cautious direction already. Eventually, there'd be a disaster, something worse than Apollo 13. NASA would have a hell of time fending off Congress after the horrific optics of dead astronauts on the Moon. At least with Apollo 1, Soyuz 1 and 11, we got the bodies back for burial.

So notwithstanding my romantic attachment to going whole hog for the Moon, I can see the wisdom in using Apollo Applications to focus on LEO for a decade or three. Risk is lower, rescue is more readily possible, and you learn more and let technology mature before you try again for the Moon. And you have some mature Saturn HLV's available once you do - unlike what obtains now, post-Shuttle.

And yes, we would have had a hell of a bigger station, many years sooner, than we got with ISS.

Thanks for the kind words.

Reading back again through your linked thread, your Option 1 - focus on the moon rather than LEO - I do agree that the LLV used by LESA was a better approach than the AES/ALSS setup. It makes maximum use of the trans-lunar payload capability of the Saturn V. Why send a crew all the way to the moon - with all the risk and cost entailed - just to ferry a LEM shelter to the surface? Well, the answer was, in large part, conservative engineering - NASA was less confident in its ability to remotely pilot the LLV to the lunar surface all the way from Earth. But that attitude might change as NASA became more confident in its systems.

I went with AES missions in the mid-1970's in my ATL simply because it was a smaller leap, easier to sell, more conservative...and it was the progression NASA was looking at in 1968 before moving to LESA. But it is quite possible that as confidence built with Apollo successes, and remote piloting technology matured, NASA might have changed its mind and skipped AES after all.

But that's details when we consider the larger policy question:

So I developed a second, much longer and detailed space ATL dealing with the above. Apollo is too risky, let's return to LEO for some decades (until 2000) until technology mature.

It takes 10 years to develop a space station (1970 to 1980) then the said space station has a useful life of 15 years (like Mir).

That bring us to 1995, except that every space station has a twin or backup, build for failure, launched later. So that's perhaps 15 more years, up to... 2010. Of course as of 1995 one can use Mir instead of launching the backup space station...

As I said, this approach has a lot to be said for it. Going to the Moon is risky. In 1968-1972, it was almost insanely risky. We bent every spar and hoisted every sail, as Jack Aubrey might say, to manage what we did, piloting a CSM a half million miles through space with a 48K RAM main computer. That was a less risk averse environment back then - you could not get away with that stuff now - but it was moving in a more cautious direction already. Eventually, there'd be a disaster, something worse than Apollo 13. NASA would have a hell of time fending off Congress after the horrific optics of dead astronauts on the Moon. At least with Apollo 1, Soyuz 1 and 11, we got the bodies back for burial.

So notwithstanding my romantic attachment to going whole hog for the Moon, I can see the wisdom in using Apollo Applications to focus on LEO for a decade or three. Risk is lower, rescue is more readily possible, and you learn more and let technology mature before you try again for the Moon. And you have some mature Saturn HLV's available once you do - unlike what obtains now, post-Shuttle.

And yes, we would have had a hell of a bigger station, many years sooner, than we got with ISS.

Some more follow up on this ATL...

After re-reading some of his earlier work on past threads, I agree with Archibold: The key "butterfly" event is eliminating Tom Paine as NASA Director and replacing him with someone more pragmatic, like George Low.

Paine was a dedicated administrator, working in very difficult circumstances, and fiercely protective of NASA's budget. But he was not the right man for the time. His unwillingness to abide by lower budget requests, and ambitious willingness to ditch Apollo for the unproven shuttle program proved more harmful than good for NASA in the long run.

So let's give this a try:

___

Narrative Background: Keeping the Dream Alive

October 1968

George Low settles in as Acting Administrator for NASA - with a full plate on his hands. James Webb had finally had enough of Houston after nearly eight years in the saddle - ironically, just as his labors were bearing fruit. Apollo was finally gearing up into high activity, with Apollo 7 demonstrating the viability of the Apollo CSM systems, notwithstanding the flu-induced rascibility of Willy Schirra and the crew - not that any of them were slated for future missions. The success of Apollo 7, however, paved the way for final approval of the more ambitious decision left on Webb's desk: the switch of Frank Borman's low earth orbit "D" mission to a "C Prime" trans-lunar mission, finessing the delays Grumman was having finishing the Lunar Module. Jim McDivitt and his crew would now launch their D mission in early 1968, assuming that Grumman had no more setbacks - but Low would drive off that bridge when he came to it.

But Low had other decision-points intersecting on his desk. It was unclear who would win the increasingly tight presidential race between Nixon and Humphrey, but no matter which man won, NASA was going to be facing an increasingly skeptical environment for its plans going forward. Budgets had been dropping steadily already since 1966, which had forced Webb to begin trimming back the Apollo Applications Program (AAP), the loose agglomeration of proposed missions that would follow the initial series of Apollo moon landings - assuming those landings happened, of course. Webb had even been forced to end the initial buy of the gigantic (and gigantically priced) Saturn V rockets just that summer. What would NASA do after it went to the Moon? Those decisions had to be made very soon. Low could fob off the decision, he mused: The NASA chief serves at the pleasure of the president, and come January 20 proximo there would be a new president. But then again, the new guy might keep him on, especially if it was Humphrey. And Low didn't care for the idea of passing the buck.

Already there was an emerging consensus on one post-Apollo element: Webb's departure and von Braun's change of heart had led to a recommendation that the long-studied orbital workshop should be a "dry" module rather than a "wet" one, requiring all equipment to be fully installed rather than simply employ an expended S-IV stage. The program as agreed by Marshall Spaceflight Center and Houston would be a core program of four launches. One Saturn V would launch the Dry Workshop Cluster, and three crews would visit for extended stays, launching on Saturn 1bs, seven of which remained available for employment. Of course, the station would require a Saturn V to launch it, and the current slate of lunar missions would consume all the available ones that were complete. Did Low have the leverage to override this consensus? It mattered, since the space station's gain would be Apollo's loss - especially if the budget for FY70 and beyond was slashed again, as seemed likely.

"Better to go with the flow on this one," he decided. The dry workshop would go ahead. But he decided one further thing: He needed to take an active hand in plotting out NASA's post-Apollo future. The new president would ask for a proposal or even a study group - and he had to be ready to shape that discussion.

February 1969

"Everyone has to take their haircut, George. That's what the boss is saying."

"I get that, Rob. I do," Low replied, gritting his teeth at OMB Director Robert Mayo through the phone. "And I can promise you that what we'll submit will be on target for that. Just bear in mind how much of this contractor work takes place in key districts..."

"You and everyone else. You think DoD isn't telling me the same story? Well, I'll look forward to seeing your proposal. With the cuts."

Low wondered if being retained as NASA head was worth the bother. Nixon had approached more than one candidate, and had been turned down flat. And no wonder, Low thought: whoever had the job would be presiding over that most unusual of creatures, the rapidly shrinking government agency. And change "shrinking" to "nonexistent" if we have another Apollo 1 disaster, especially in space, Low mused. Nixon was driving hard for a more balanced budget, and the word had gone out to the agencies and departments: Don't submit a budget without a reasonable cut. Low wryly recalled Webb's old plea after first getting the Moon mandate from JFK: "Does anyone here want my job?"

"The more things change..." he mused. Apollo Applications was already on life support, with an eye on the funeral parlor; now Low wondered how much of Apollo proper would survive. As it was, he would need to cut a mission to get the Saturn V needed to loft the space station, now tentatively called "Skylab." After all, it was by no means certain that he could find the money to finish out the two unfinished rockets, SA-516 and 517. So much for Apollo 20. Low looked at the rough draft again: Just $2.17 billion for manned spaceflight this year. In five years, he thought, we might be lucky to have a billion at this rate. Especially if Vietnam drags on - as seemed likely. The future ain't what it used to be.

As a Democrat holdover, Low knew he had even less leverage with Nixon, even if he had a perverse kind of protection by burnishing Nixon's bipartisan credentials just by his existence. But he also knew his man: Nixon would not fund the kind of extravagant missions bandied about in NASA's salad days - just a few years ago! he reflected bitterly - but he would also not go out of his way to kill NASA. Conservative is the way to go. Forget Mars. Forget Venus. Forget asteroid missions. Forget reusable space shuttles. Focus on what's working. And what's working is Apollo.

Inertia would carry NASA through, Low reflected - albeit on lean rations.

After re-reading some of his earlier work on past threads, I agree with Archibold: The key "butterfly" event is eliminating Tom Paine as NASA Director and replacing him with someone more pragmatic, like George Low.

Paine was a dedicated administrator, working in very difficult circumstances, and fiercely protective of NASA's budget. But he was not the right man for the time. His unwillingness to abide by lower budget requests, and ambitious willingness to ditch Apollo for the unproven shuttle program proved more harmful than good for NASA in the long run.

So let's give this a try:

___

Narrative Background: Keeping the Dream Alive

October 1968

George Low settles in as Acting Administrator for NASA - with a full plate on his hands. James Webb had finally had enough of Houston after nearly eight years in the saddle - ironically, just as his labors were bearing fruit. Apollo was finally gearing up into high activity, with Apollo 7 demonstrating the viability of the Apollo CSM systems, notwithstanding the flu-induced rascibility of Willy Schirra and the crew - not that any of them were slated for future missions. The success of Apollo 7, however, paved the way for final approval of the more ambitious decision left on Webb's desk: the switch of Frank Borman's low earth orbit "D" mission to a "C Prime" trans-lunar mission, finessing the delays Grumman was having finishing the Lunar Module. Jim McDivitt and his crew would now launch their D mission in early 1968, assuming that Grumman had no more setbacks - but Low would drive off that bridge when he came to it.

But Low had other decision-points intersecting on his desk. It was unclear who would win the increasingly tight presidential race between Nixon and Humphrey, but no matter which man won, NASA was going to be facing an increasingly skeptical environment for its plans going forward. Budgets had been dropping steadily already since 1966, which had forced Webb to begin trimming back the Apollo Applications Program (AAP), the loose agglomeration of proposed missions that would follow the initial series of Apollo moon landings - assuming those landings happened, of course. Webb had even been forced to end the initial buy of the gigantic (and gigantically priced) Saturn V rockets just that summer. What would NASA do after it went to the Moon? Those decisions had to be made very soon. Low could fob off the decision, he mused: The NASA chief serves at the pleasure of the president, and come January 20 proximo there would be a new president. But then again, the new guy might keep him on, especially if it was Humphrey. And Low didn't care for the idea of passing the buck.

Already there was an emerging consensus on one post-Apollo element: Webb's departure and von Braun's change of heart had led to a recommendation that the long-studied orbital workshop should be a "dry" module rather than a "wet" one, requiring all equipment to be fully installed rather than simply employ an expended S-IV stage. The program as agreed by Marshall Spaceflight Center and Houston would be a core program of four launches. One Saturn V would launch the Dry Workshop Cluster, and three crews would visit for extended stays, launching on Saturn 1bs, seven of which remained available for employment. Of course, the station would require a Saturn V to launch it, and the current slate of lunar missions would consume all the available ones that were complete. Did Low have the leverage to override this consensus? It mattered, since the space station's gain would be Apollo's loss - especially if the budget for FY70 and beyond was slashed again, as seemed likely.

"Better to go with the flow on this one," he decided. The dry workshop would go ahead. But he decided one further thing: He needed to take an active hand in plotting out NASA's post-Apollo future. The new president would ask for a proposal or even a study group - and he had to be ready to shape that discussion.

February 1969

"Everyone has to take their haircut, George. That's what the boss is saying."

"I get that, Rob. I do," Low replied, gritting his teeth at OMB Director Robert Mayo through the phone. "And I can promise you that what we'll submit will be on target for that. Just bear in mind how much of this contractor work takes place in key districts..."

"You and everyone else. You think DoD isn't telling me the same story? Well, I'll look forward to seeing your proposal. With the cuts."

Low wondered if being retained as NASA head was worth the bother. Nixon had approached more than one candidate, and had been turned down flat. And no wonder, Low thought: whoever had the job would be presiding over that most unusual of creatures, the rapidly shrinking government agency. And change "shrinking" to "nonexistent" if we have another Apollo 1 disaster, especially in space, Low mused. Nixon was driving hard for a more balanced budget, and the word had gone out to the agencies and departments: Don't submit a budget without a reasonable cut. Low wryly recalled Webb's old plea after first getting the Moon mandate from JFK: "Does anyone here want my job?"

"The more things change..." he mused. Apollo Applications was already on life support, with an eye on the funeral parlor; now Low wondered how much of Apollo proper would survive. As it was, he would need to cut a mission to get the Saturn V needed to loft the space station, now tentatively called "Skylab." After all, it was by no means certain that he could find the money to finish out the two unfinished rockets, SA-516 and 517. So much for Apollo 20. Low looked at the rough draft again: Just $2.17 billion for manned spaceflight this year. In five years, he thought, we might be lucky to have a billion at this rate. Especially if Vietnam drags on - as seemed likely. The future ain't what it used to be.