Chapter 20

And Forever Undivided

“Ubi Rex meus, ibi Regnum meum”

Where my king is, there my kingdom is.

- Queen Elisabeth, 1522[1]

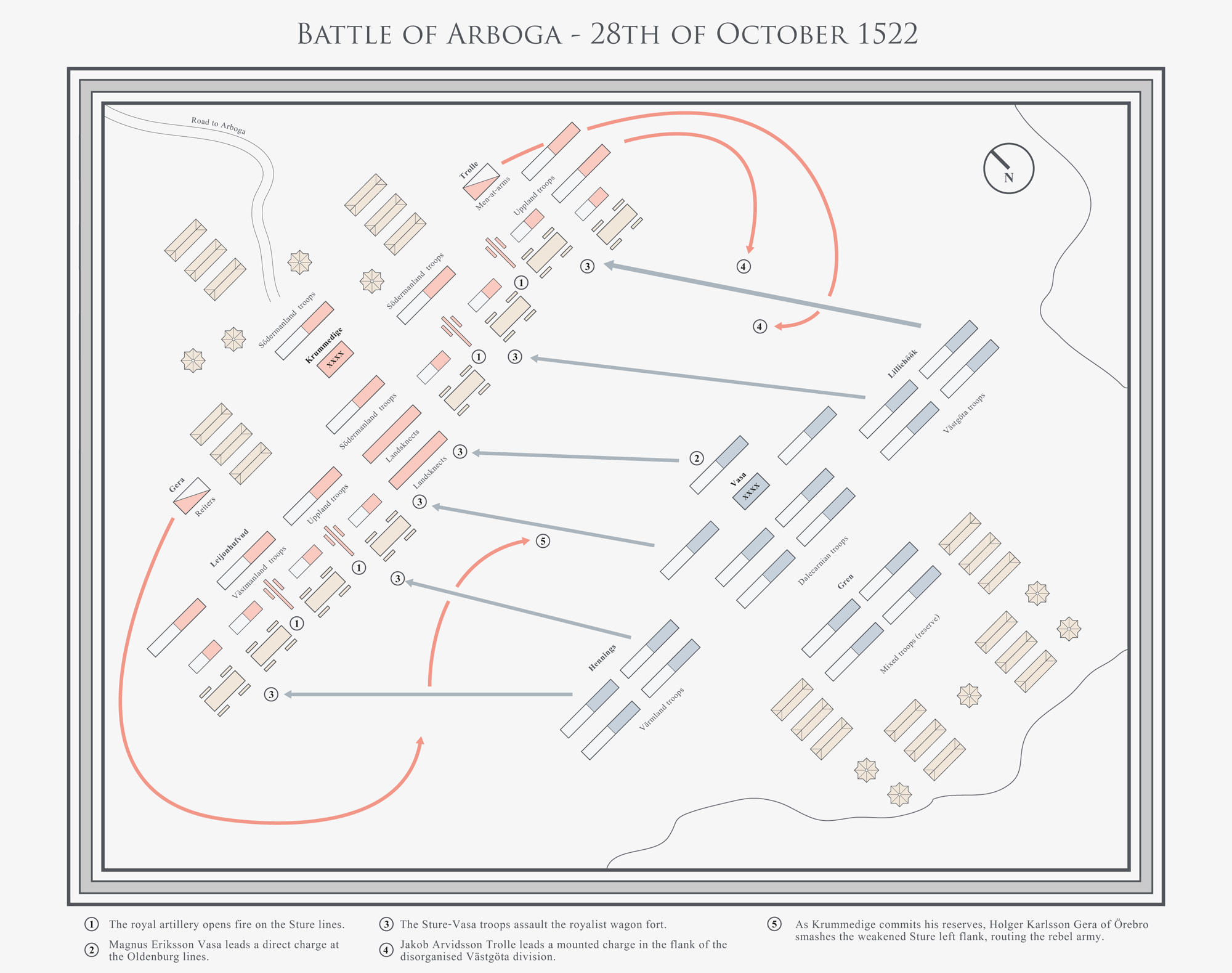

The Battle of Hillerslev was not the only major engagement of the autumn of 1522. On the 27th of October, Henrik Krummedige and Erik Abrahamsson Leijonhufvud faced off the Sture rebels under Magnus Eriksson Vasa, Vincent Hennings and Måns Bryntesson Lilliehöök on the fields just outside the town of Arboga. The forces of the

Rikshövitsman numbered some 10.000 peasants from Dalarna, Värmland and Västgötland, but little cavalry and next to no artillery

[2]. Conversely, the union army possesed amble ordinance. Krummedige had scoured Stockholm harbour and castle for guns and ammunition and could as such field a respectable artillery corps - an advantage that worried many in the Sture-Vasa camp.

Additionally, the viceroy had obtained several loans from the city of Stockholm (a personal possession of the Oldenburg monarchy after the 1520-peace treaty) through which the number of Landsknecht infantry

fähnleins had been doubled, totalling some 1000 men. Combined with the 6000 peasant soldiers drummed up by the efforts of the pro-unionist agitation of Leijonhufvud and Hemmingh Gadh, the royalist army in Sweden was thereby numerically outnumbered by some 3000 troops, but maintained superiority in both mobility and firepower. This did not deter the Lord Captain, who confidently told his Västgöta supporters that they soon would disperse “...

that rabble of Jutes.”

[3]

As the two sides drew up their battle lines the following day, the air was chilled by the onset of an early winter frost. Trusting his artillery to force an enemy assault, Krummedige arrayed his supply train in a defensive wagon fort

[4] behind which he deployed his infantry armed with pikes, crossbows and hand-guns. The mounted retainers of Holger Karlsson Gera and Jakob Arvidsson Trolle were in turn kept to the rear whilst Henrik Krummedige himself commanded the centre. His personal guard of Scanian noblemen gathering around a large heavy battle standard bearing the three crowns of the union coat of arms superimposed over the Oldenburg colours.

The battle was initiated by a flurry of cannon fire from the crown’s batteries, to which the Lord Captain was incapable of responding. The Sture chronicle woefully notes that “...

all the courage of the Swedish commoner was for naught for want of gun and powder.” Furrows of lead and limps ploughed through the rebel battle squares, prompting Magnus Eriksson to order an all out assault on the royalist position, entirely in tune with Krummedige’s prediction. Riding along the front line, the Lord Captain was heard to call out “...

if God is with us, then who can oppose us?”

[5] However, in the words of a later historian, it would turn out that on that day the good Lord was busy elsewhere. For all his immaculate anti-unionist pedigree, the younger Vasa was an inexperienced commander who lacked the tactical skill of his forebears. Henrik Krummedige, conversely, was a veteran of a dozen battles and fiercely determined to end Eriksson’s rebellion and restore “...

good governance and just peace to the realm of Sweden, free of seditious insurrection.”

As the Sture host advanced, their cohesion wobbled under the enemy barrage, which given the fact that a majority of the army was composed of raw recruits, proved to be a decisive moment. The first rebel wave shattered against the wagon-fort, unable to penetrate the loyalist defences. Eriksson’s Dalecarlian diehards made a valiant charge in the centre, but the German and Baltic mercenaries repelled their onslaught again and again. As the two sides locked pikes, Krummedige signalled for Gera and Trolle to lead their knights around the rebel line. The thundering hooves of the union’s advancing cavalry sent a shiver of foreboding through the entangled melee. When the first armoured destriers hammered into the exposed flanks of the Sture peasant army, anticipation turned into panic as scores of Värmland and Västgöta freemen fled for their lives.

Magnus Eriksson was caught between the hammer and the anvil. His blue and white striped banner

[6], the combined escutcheon of the Bonde monarchy and Sture stewardship embroidered in the centre, fell to the ground and was picked up time after time, as his standard bearers were cut down. As the noble retainers paved a bloody path through the retreating rebels, the loyalist peasant troops unhinged the linked wagons and streamed forth to bludgeon the already badly beaten Sture formations. Too late, the Lord Captain realised his desperate situation. By all appearances, Eriksson was trying to fight his way back to his remaining reserves when his horse was brought down by either a crossbow bolt or musket ball, trapping him beneath the panicking steed. Seeing their leader fall, what little fight remained in the Sture host evaporated. In the ensuing rout Lilliehöök managed to extricate himself at the head of a sizeable contingent, but bishop Vincent Hennings of Skara was captured by Leijonhufvud’s retainers, leaving Krummedige’s forces victorious and in sole command of the field.

Magnus Eriksson’s crushed body was dug out from beneath his steed and unceremoniously interred in a mass grave alongside the bodies of the 3000 Dalarna, Västgöta and Värmland troops killed in the battle. Vincent Hennings was clasped in irons and sent to Stockholm to await the king’s justice, whilst the royalist commanders prepared to restore order to Närke and the other fiefs still in rebel hands.

The Battle of Arboga would be the pivotal moment in the Sture-Vasa rising in Västergötland.

News of the Battle of Arboga reached the king at Odense a fortnight after he had crushed the Frederickians at Hillerslev: the city being taken in the immediate aftermath of the fighting. As the royal outriders approached the city walls, the burghers within overpowered the small ducal garrison and opened the gates for the returning king. As such, the Oldenburg host entered the Funen capital to the sound of chiming bells from Saint Canute’s Cathedral and the unabated cheers of the commons. Whilst the king took up residence at Næsbyhoved castle, the royal army encamped itself in the Odense hinterlands - its myriad of tents signalling the crown’s restored dominion over the island.

From Næsbyhoved, the royal chancery issued a storm of summons to the local nobility, commanding them to appear at the king’s court before the end of the month. As one contemporary chronicler noted, the Funen gentry feared that the king would reward their decidedly unenthusiastic resistance to the Gottorp pretender with “...

noose and sword.” Given the summarily execution of the duke’s main Jutish commander after Hillerslev, one could hardly blame them for doubting the king’s penchant for mercy. However, it soon became apparent to the nobility that Christian II had no use for their necks. Rather, it was their purses he coveted.

The Odense

herredag (literally Lords’ Day) therefore more resembled an armed hold-up than any judicial reckoning. Nobles such as Anders Jakobsen Reventlow (enfeoffed with the fief of Salling) were confirmed in their feudal holdings, but had to remit the debts owed them by the crown. This had the added benefit of drastically increasing the number of account fiefs within the realm, ensuring an overall increase in profit for the royal exchequer.

With Funen pacified, Christian II crossed the Little Belt and made landfall outside Hønborg castle on November 26 1522. Wading ashore through the shallows, the king fell to his knees on the Jutish winter beach, kissed the sea-weed and pebble strewn sand before gravely making the sign of the cross. As he clasped his hands in prayer, his companions are said to have heard him mutter Psalm 43: “...

Vindicate me, O Lord, and plead my cause against an unfaithful nation. Rescue me from those who are deceitful and wicked.”

[7] Although victorious at land and sea, Christian II was nevertheless not going to take any chances by spurring the almighty. The quote is most likely apocryphal, but the ensuing events have lent it a cloak of credibility that has permeated through the ages.

By the time the king had landed in Jutland, the political landscape of the peninsula had dissolved into a state of flux. In the north and north-east, the burgher-general Clement Andersen had swept the forces of the Lords Declarent aside - linking arms with Erik Eriksen Banner, who in turn had brought his ordnance and garrison of professional soldiers up from Kaløhus. Together, the pair marched their combined forces towards Aarhus, liberating it after a brief skirmish with a cavalry detachment loyal to the bishop of Viborg. Seeing their military strength evaporating little by little, the remaining members of The Council of Denmark’s Realm in Jutland Declared, decided to evacuate the royal part of the peninsula and instead make their stand in the duchies alongside the new champion of the Frederickian cause - the king’s cousin, Christian duke of Holstein

[8]. As one contemporary chronicler dryly commented “...

all that was left to those lords was the hollowness of their declaration.”

The Army of Christian II Seizes Koldinghus. From the Oldenburgische Chronicon

by an unknown artist, ca. 1563-99.

From Hønborg, the royal army advanced on Koldinghus, where the ducal garrison surrendered without a fight. Emerging from the dungeons was a limping, but undaunted Henrik Gøye who had spent the past few months in captivity, recuperating from the wounds he received at the skirmish on the 17th of May. All accounts concur that Gøye’s liberation made for an extremely gratifying moment for the king. Mimicking his reception of Søren Norby at the Bremerholm after the Battle of Nyborg, Christian II himself tied a sword-belt around Gøye’s waist: asking him whether or not he would be prepared to draw it again in defense of the realm and his sovereign. When Henrik Gøye answered in the affirmative, the king proclaimed him his ‘marshal of the border’ and enfeoffed him on the spot with the castles of Ribe- and Koldinghus, the latter as a lifelong service fief

[9].

Setting up court at Kolding, Christian II commissioned sirs Anders Bille and Mogens Gyldenstjerne with leading a part of the royal main army north towards Skanderborg, where they in conjunction with Erik Eriksen Banner and Clement Andersen were to seize the castle and then subjugate the rebel stronghold of Viborg. Decimated by the defeat at Hillerslev and the subsequent “

flight of the bishops” to Holstein, the remaining forces of the Lords Declarent were unable to resist the crown’s advance. As such, when Christian II celebrated Christmas at St. Nicolai’s church his captains had restored the crown’s authority throughout the peninsula north of the King’s River

[10].

To the south, Christian II’s allies had finally risen to the occasion. Whilst the king’s captains marched up and down Northern Jutland driving the rebels before them, Albrecht VII of Mecklenburg had taken the field against the Hansa. Augmenting his war chest with decent subsidies from the Hohenzollern court in Berlin, Albrecht first struck against the city of Rostock - situated to the immediate north of his ducal see of Güstrow. As the Mecklenburg army appeared before the decrepit city walls of Rostock, the town’s Hanseatic burghers and mayors were quick to jettison any ties to the Wendish Hansa. Albrecht graciously accepted the town’s surrender, although he made sure to leave behind a garrison to ensure the Rostockians’ newfound adherence to the House of Mecklenburg.

The ground was thus burning under the feet of the Wendish Hansa as the year 1523 began. By February, Christian II had consolidated the royal armies at Koldinghus with the intent to finally humble “...

those arrogant and prideful Holstenians”

[11].

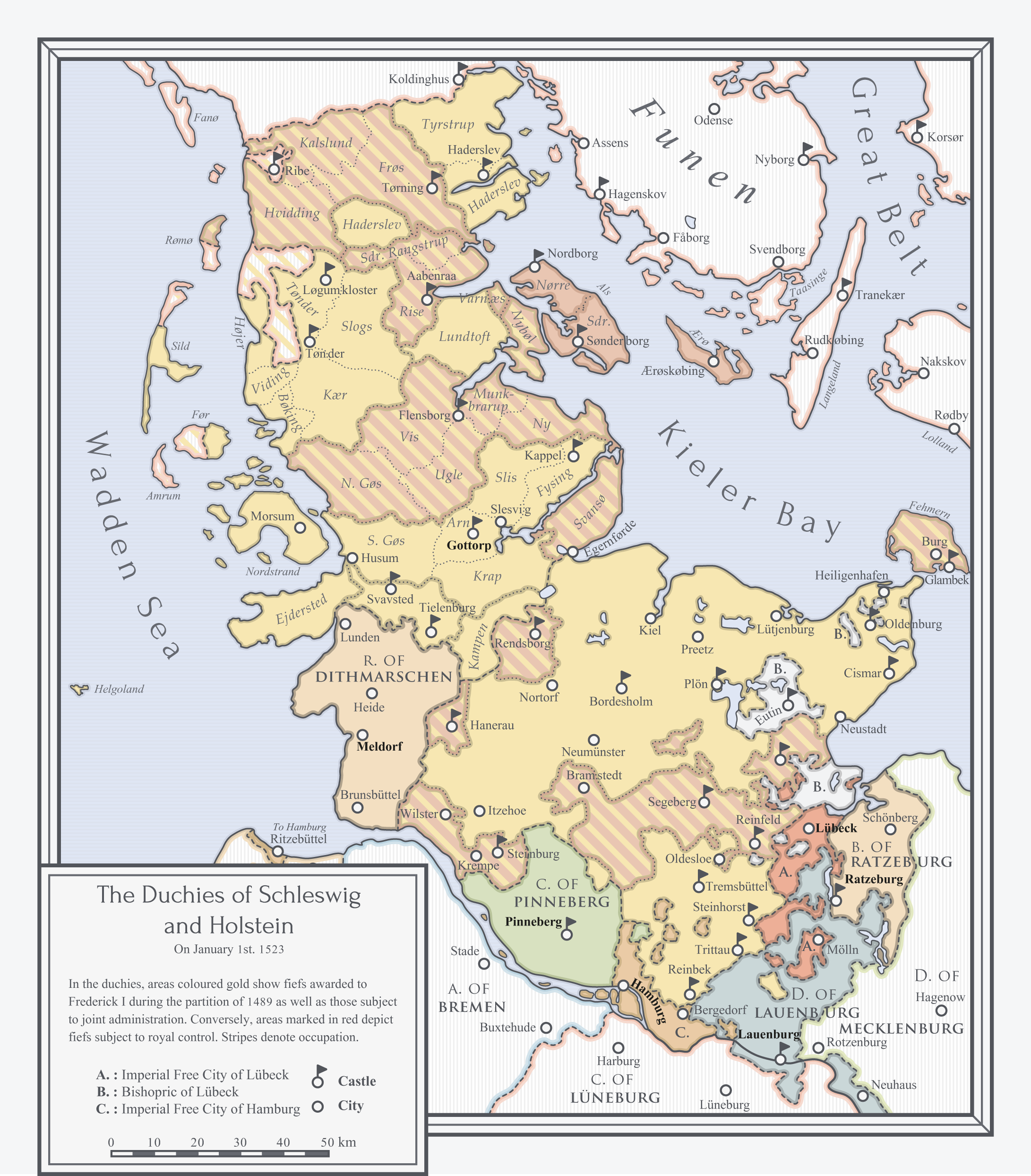

However, the invasion of the duchies had in effect already begun. On Christmas Day 1522, Søren Norby and the royal fleet had appeared off the island of Als. Debarking outside the castle of Sønderborg, Norby himself led the night-time assault on the castle walls (reminiscent of his taking of Öland four years before), the king’s chain of the Golden Fleece flashing upon his breastplate in the moonlight. The ducal defenders were few and unpaid and by morning, the Oldenburg banner once more fluttered over the battlements. Sønderborg thus became the first part of the occupied duchies to be liberated by the crown’s forces.

Soon thereafter, Nordborg, the strong castle guarding the island’s northern tip, was seized through the ingenious subterfuge of Wolf Pogwisch, the castle’s erstwhile commander

[12]. The capture of Als severely weakened the Gottorpian position in Schleswig by exposing most of the peninsula’s eastern seaboard to attack. Already, the burghers of Flensborg and Aabenraa were getting restless and it was greatly feared in the Frederickian war council that a two-pronged attack from Jutland and the royal strongpoints on the isles would be combined with insurrections in the countryside. Consequently, Christian III of Holstein decided to make his stand in the southernmost part of the duchy, near his personal stronghold of Gottorp, where he had been joined by the three renegade bishops of the Lords Declarent.

Map of the military-political situation in the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, early 1523. The duchies of Schleswig and Holstein had been divided between Hans I and Frederick I in 1489/1490 as a part of a larger settlement between the brothers. In Holstein, some areas were supposed to be governed jointly by the two co-dukes. However, when Frederick raised the banner of revolt against Christian II these fiefs went over to the king's uncle all as one. As such they're not shown independently on the map, but rather as part of the ducal/Gottorpian domains.

On Candlemas-day 1523, Christian II crossed the King’s River at the head of an army some 6000 strong. At its core were the six battle-hardened fähnleins of Landsknecht infantry that had carried the day at Hillerslev as well as, what one scholar once termed the “...

most formidable train of artillery that had ever been seen in the Danish realm.” In the van, the count of Hoya’s reiters and the assembled might of the rostjeneste swept ahead of the main force whilst the rear was brought up by Clement Andersen’s burgher troops. In other words the king was leading an army into Schleswig capable of not just destroying the Gottorpian remnants, but one which could cement royal authority throughout the seditious Elbe-provinces and once and for all break the independence of the strong-willed Holstenian nobility.

Just as the rebels had feared, the occupied royal fiefs in Schleswig immediately went over to the crown, the moment Anders Bille’s cavalry appeared. In Flensborg, a noble named Detlev Brockdorf

[13] led a force of burghers and peasants through the city gates and confined the small gastle garrison. The arrival of seaborne reinforcements under the command of Tile Giseler eventually forced the defenders to surrender. Even in Haderslev, a city which had long enjoyed the patronage of the Gottorp duke, the locals willingly opened their gates for the king’s outriders and arrested the ducal constable

[14].

By all accounts the nobility of the duchies was acutely aware of what danger the invasion posed to their hardwon privileges. Unfortunately, at this vital moment the Holstenian gentry was deeply divided. The all-powerful Rantzau family had forsworn any further participation in the Frederickian cause as long as Johann von Rantzau remained the king’s captive in the Blue Tower. Others, such as the von Rathlows

[15], argued that the best cause of action would be to seek terms with the ascending monarchy. Militarily, they claimed, nothing could be achieved against the power which was now descending upon them.

As such, when Christian III called his banners only a fraction of his on paper strength materialised. Two fähnleins had arrived from Lübeck, but they had not been paid in months. Possibly as many as 4000 Frisian peasants had mustered outside the walls of the ducal see, but they in turn were raw recruits, who would be made mincemeat of by the first charge of the royal infantry.

When rumors spread that Søren Norby had landed a force near Eckerførde, Christian III decided to fall back into Holstein. However, his landsknecht companies refused to march without pay and effectively went into strike, threatening to sack the city of Slesvig if their demands were not met

[16]. Seeing everything seemingly fall apart before his eyes, the duke supposedly quipped to Wolfgang von Uttenhof that it would be ill to welcome his “...

good sir cousin when he is armoured thus and I am not.”

[17] Leaving his ancestral see in the hands of a trusted advisor, Christian III fled south to Bordesholm where he gathered a troop of some 200 diehard supporters - as well as his stepmother Sophie of Pomerania, his sister Dorothea and young half-brother, Hans.

It was probably in the council hall of Bordesholm that the duke resolved to go abroad. Militarily he could not hope to prevail, nor did he place much trust in the king’s mercy, seeing the fate which had befallen the other prominent leaders of the revolt. However, the arrival of troops under the Duke of Mecklenburg on the banks of the Elbe prevented Christian from going East to the court of Bogislaw X of Pomerania. Some consideration was given to seeking refugee in the domains of Henry, duke Braunschweig-Lüneburg, but Jørgen Friis counselled against it, arguing that nowhere within the empire would be safe for them as long as Charles V drew breath. Consequently, on the third of March 1523 the Gottorpian entourage crossed into the duchy of Pinneberg, wherefrom it swiftly made way for Hamburg. There a small squadron of ships laid anchored ready to carry the duke and his supporters into exile. Thus it came to pass that when Christian II triumphantly entered Gottorp Castle his cousin was sailing off for an uncertain future at the court of Francis I in Paris.

The Castle of Segeberg. Cut-out from a contemporary illustration by an unknown artist, ca. 1540. Situated on a 120 meter high mountain of chalk and Gypsum, the castle was one of the strongest military positions in the duchy of Holstein.

The departure of duke Christian had loosened the last knot tying the Frederickian cause together. Without a pretender to support, the two fähnleins employed by Lübeck had marched home, harrowing the countryside as they left (a fact which greatly improved the king’s standing amongst the peasantry) and the Frisian levies had done the same - returning to their marshy farmsteads.

By the end of March, Christian II had effectively seized the whole of Holstein. The only opposition to his governance had been a small force of desperate Holsteinian nobles and levied peasants which Anders Bille smashed at Neumünster. Setting up court at Segeberg

[18] the king summoned the Estates of the Duchy “...

to answer for their crime of rebellion and to seek a lasting peace for the country.” However, the equestrian gentry escaped the collapse of the Ducal Feud remarkably unscathed. Besides a the expected torrent of stark fines and expropriations, remarkably few death sentences were passed by the royal court - the latter chiefly relating to those nobles who had chosen to join the king’s cousin in exile.

It would, however, soon become apparent that the Holstenians were to pay dearly for their sedition by other means. As the court drew to a close, Christian II asked the representatives of the estates to affirm the reconciliation with a treaty, which in effect would completely alter the constitutional position of the duchy.

First of all, the king demanded that the stipulations of the 1460 Treaty of Ribe be reaffirmed - namely that the two duchies should “...

remain forever united and indivisible.”

[19] The hitherto practice of splitting the duchies between the heirs of a deceased duke was precisely what had enabled Frederick I to rise to such a powerful position within the realm, something the crown could not allow to happen again. By forcing the gentry to accept himself as the sole duke his son prince Hans as the the sole heir to the undivided duchies, Christian II removed one of the most dangerous feudal institutions in the Oldenburg composite state. However, just as important was the fact that the treaty formalized the 1521 change of enfeoffment granted by Charles V in Brussels, de facto making the king his own feudal overlord in Holstein, answerable only to the emperor.

The Segeberg Accord was sealed with a week’s worth of feasting and tournaments, culminating in the nomination of Otte Krumpen as stadtholder of Holstein whilst Henrik Gøye was named governor of Schleswig. This appointment constituted the high-water mark of the Gøye family’s fortunes. As the king’s first representative in Schleswig, with command over the castles of Ribe- and Koldinghus, Henrik Gøye was undoubtedly the one man to make the most of the feud. Many others would not be so fortunate. When Christian II left the duchies on April 13th 1523 he made a point of not dismissing even half of his mercenaries. Instead he brought the royal army north to Viborg where not only the council of the realm had been summoned, but representatives of the other estates as well. As Poul Helgesen wrote admiringly “...

a hard winter has passed. God pray that a glorious summer is about to begin.”

Footnotes

[1] OTL quote, from a letter to Frederick I, refusing his offer of amnesty and a generous pension, if the queen were to abandon her husband.

[2] ITTL, the Sture rebels have a much tougher time gathering support than Gustav Vasa did. As such, they have secured no important castles and have little to no support from the Hansa, limiting their armaments.

[3] An OTL quote by Ture Jönsson in 1522. Originally he was referring to the Danish garrison in Oslo as “...

then Jutehop på Biskopsgården.”

[4] Although most often associated with the Hussites, the tactic was quite widespread in northern Europe. For example, it was used during the Count’s Feud in Denmark.

[5] An OTL quote by Gustav Vasa.

[6] An OTL banner used by the Swedes before the introduction of the blue and yellow Nordic cross flag.

[7] As Henry VII did when he landed at Pembrokeshire in 1485.

[8] Now it gets really confusing.

[9] Both fiefs had become vacant after the executions of Oluf Nielsen Rosenkrantz and Predbjørn Podebusk.

[10] Kongeåen, or in English - the King’s River, was the historical border between Northern Jutland and Schleswig.

[11] A slightly rewritten OTL quote made by the king in 1521.

[12] In OTL Wolf Pogwisch refused to surrender the castle to the rebels, only yielding it after all hope had been lost.

[13] Who previously defended Flensburg against the Gottorpians. As he did in OTL.

[14] In OTL, the peasantry actually attempted to raise an army against the Gottorp pretender once Frederick claimed the throne.

[15] Next to the Rantzau family, the Ranthlows were one of the most powerful Holstenian noble families at this point in time.

[16] This happened to Frederick I in OTL as well. Only loans and guarantees from Lübeck got his army marching at that point (which was before he had even crossed onto Funen) - a support which his son can’t count upon given the desperate situation.

[17] When Christian II met his cousin in 1521 prior to some negotiations about the status of the duchies, he rode up to him whilst jokingly drawing his sword and saying “...

Gee, good sir cousin are you also going well armoured to the meeting?” (own somewhat loose translation).

[18] The strongest royal castle in Holstein. ITTL as well as in OTL, the castle had been well-provisioned with gunpowder and other munitions and as such posed a severe threat to Frederick I. However, in OTL the commander, Jürgen von der Wisch, surrendered the castle after a truce lasting barely a fortnight - something both queen Elisabeth and Søren Norby bitterly resented.

[19] The original reads “...

dat se bliven ewich tosamende ungedelt”

It’s always a joy to read an alt TL about a united Scandinavia, and the levels of detail in this one is incredible. I especially have a fondness for the maps.