Chapter 1

With Only Beetles at His Side

In February 1513, king Hans of Denmark fell off his horse and plunged into the swollen and marshy waters of the Skjern River in Western Jutland. Grievously injured, the king was taken to the city of Aalborg, whereto he had already summoned a number of Jutish councilors of the realm. After a few days, Hans, the second of the Oldenburg dynasty, king of Denmark, Norway and Sweden committed his soul to God, and died.

The king’s reign had been a troubled one and the results of it a mixed bag. He had fought the Swedes and won, successfully restoring the Kalmar Union. He had fought the peasant republic of Dithmarschen in the Battle of Hemmingstedt, and suffered a crushing defeat. The loss of prestige was so grievous that the anti-union party in Sweden once more took up the cause of separation, and allied with the king’s old foes in the Haseatic town of Lübeck, waged war against the king. However, the newly established royal navy proved to be too great a foe for the allies in the war at sea, and at the subsequent Peace of Malmø in 1512, the union was once more upheld, the Swedish council of the realm being obliged to recognize the king’s son and heir, Christian, as the next king of Sweden.

The Adoration of the Magi by the Master of Frankfurt

, a Flemish painter active in Antwerp ca. 1520. Altarpiece from the House of the Holy Ghost, Nykøbing-Falster, Denmark. On the left panel, Balthazar, true to renaissance tradition, is depicted as a young moor observing the holy family, holding his gift of Myrrh. In the central panel, the holy family receives the adoration of Caspar (in the likeness of King Hans I), kneeling in prayer before the Infant Christ, who smilingly reaches out for the old man. On the final panel of the triptych, young Melchior (depicted as Christian II) steps into the barn, tipping his crowned hat in greetings with his right hand grasping the gift of gold, symbolizing Christ’s divine kingship. In the middle the coat of arms of the house of Oldenburg is shown.

However, Christian’s very ascension to the throne of Denmark was in no way certain. His father had governed the realm in a remarkably headstrong way, disregarding his accession charter and placed commoners and burghers as fief holders at important royal castles, a right to office usually and legally reserved for those belonging to the nobility. Prince Christian, who had accompanied his sire on the journey to Aalborg was at the king’s side when he passed and he swiftly moved to secure the loyalty of the noble magnates gathered in the city. Despite the fact that the royal council on three occasions had sworn to make Christian their king after his father, the assembled lords refused outright to proclaim him ruler before a new accession charter had been formulated and the remainders of the council and estates had been heard

[1]. After a heated exchange, the two parties split in anger. In the words of the Swedish nobleman and commander at Älvsborg castle, Ture Jönsson, reporting on the events after the king’s passing, the prince found few friends amongst the upper aristocracy as:

“...ere hannem jnge tiilfalne ythen de Byller.”

“...none have come to his side other than those Beetles.”[2]

These so-called Beetles were the members of the House of Bille, one of the more prominent families within the realm. The ecclesiastically educated Ove Bille had been the late king’s chancellor whilst his brother Eske served as castellan and fief-holder at Copenhagen castle. Both brothers had thus occupied important positions within the administration, but their unwavering support was a rarity. Although certain members of the high nobility were sympathetic to the young prince, such as the immensely rich and powerful Gøye-family, the aristocracy as a whole had its own best interests at heart.

The constitutional precedent was clear. No king could be elected until he had signed an accession charter, formulated in concert with the councilar nobility and church prelates. To accept the prince as king without any royal concessions or confirmation of the aristocracy’s feudal privileges, as Christian had demanded in Aalborg, would be to poison to the very institution of the elective monarchy. Consequently, the lesser nobility and the councils of all three union realms were issued a summons, to appear in Copenhagen in the summer of 1513 to negotiate the terms of a new charter.

Although the commoners and burghers had received the handsome and strapping-looking

[3] prince ecstatically

[4] upon his return from Norway, the high nobility had good cause to be alarmed at the prospect of Christian assuming the throne. During his tenure as viceroy, Christian had forcefully advanced the cause of the crown, effectively ruling the country in a proto-absolulist manner, at the expense of both the worldly aristocracy as well as the church’s prelates. He had all but obliterated the Norwegian council of the realm as an independent political entity and brought the strong-willed Norwegian church to heel by outright imprisoning a bishop of the church who stood in his way. King Hans too, had flaunted the constitutional restraints placed upon him by his own charter, and now it seemed his as if his son would follow in his footsteps at a marching pace.

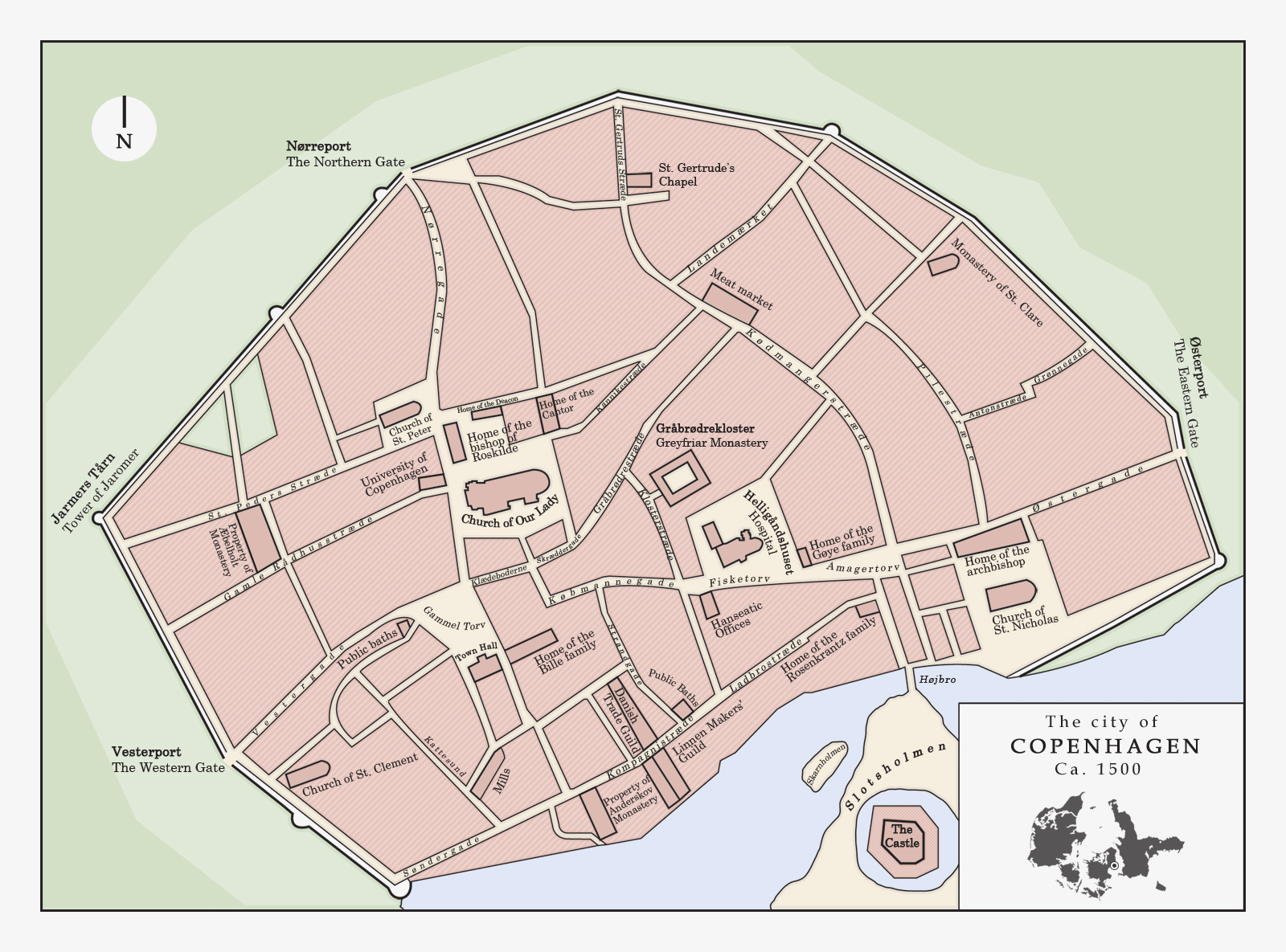

The city of Copenhagen had in the course of the 15th century evolved into a respectable royal and national capital thanks to its location in the centre of the Danish realm.

Two groupings within the aristocracy came up with separate ideas of constraining the head-strong would-be monarch. One faction, rallying around the Jutish nobility and knights under the leadership of Predbjørn Podebusk, fief-holder at Riberhus and councilor of the realm, wanted to simply bypass the prince and offer the crown to his uncle, Frederick, the duke of Holstein

[5]. However, to the chagrin of the conspirators, the skillful political operator Frederick rejected the proposal of the conspirators, who instead joined forces with the second oppositional grouping: the aristocratic constitutionalists.

Taking the lead in the councilar aristocracy’s opposition was the archbishop of Lund, Birger Gunnersen. Gunnersen had risen to his high office as the leader of the Scandinavian church from a remarkably lowborn background (his father had been a mere provincial bellringer in Halland) with the support of king Hans. However, the archbishop firmly believed in the independence of the church, and Christian’s numerous feuds with the Norwegian church as well as his involvement in disrupting Gunnersen’s ambition to choose his own successor had turned the prelate firmly against the crown and into an alliance with his old foes in the aristocracy

[6].

The archbishop helped formulate a damning indictment of his old friend and protector, king Hans’ rule. Of the 51 articles in the late king’s charter, 30 had supposedly been violated, including particularly grave issues such as the execution of members of the high nobility without due process, the appointment of commoners as fief-holders and the waging of war without the consent of the council of the realm. In order to prevent a further deterioration of the nobility’s control with the monarchy, the aristocratic constitutionalists demanded the inclusion of several new articles and the dismissal of all burgher fief-holders.

Fiefs were the building blocks of power politics in late-medieval Scandinavia and the control of these were consequently of immense economic and political importance. Christian was forced to accept the removal of the commoner castellans, marking an important win for the councilar opposition, but the prince conceded graciously and without much fuss, persuaded in part by his own noble supporters and friends

[7]. Although he himself had lived at the home of a prominent Copenhagen trader as a child, and consequently held the burghers and commoners in high regard as possible allies of the crown, the prince understood full well the tactical necessity of placating the council of the realm. Although the burgher fief-holders were utterly dependent on the crown for their advancement and thus only owed the king their loyalty, it would be a small loss for the king to replace one supporter with another of a higher social standing.

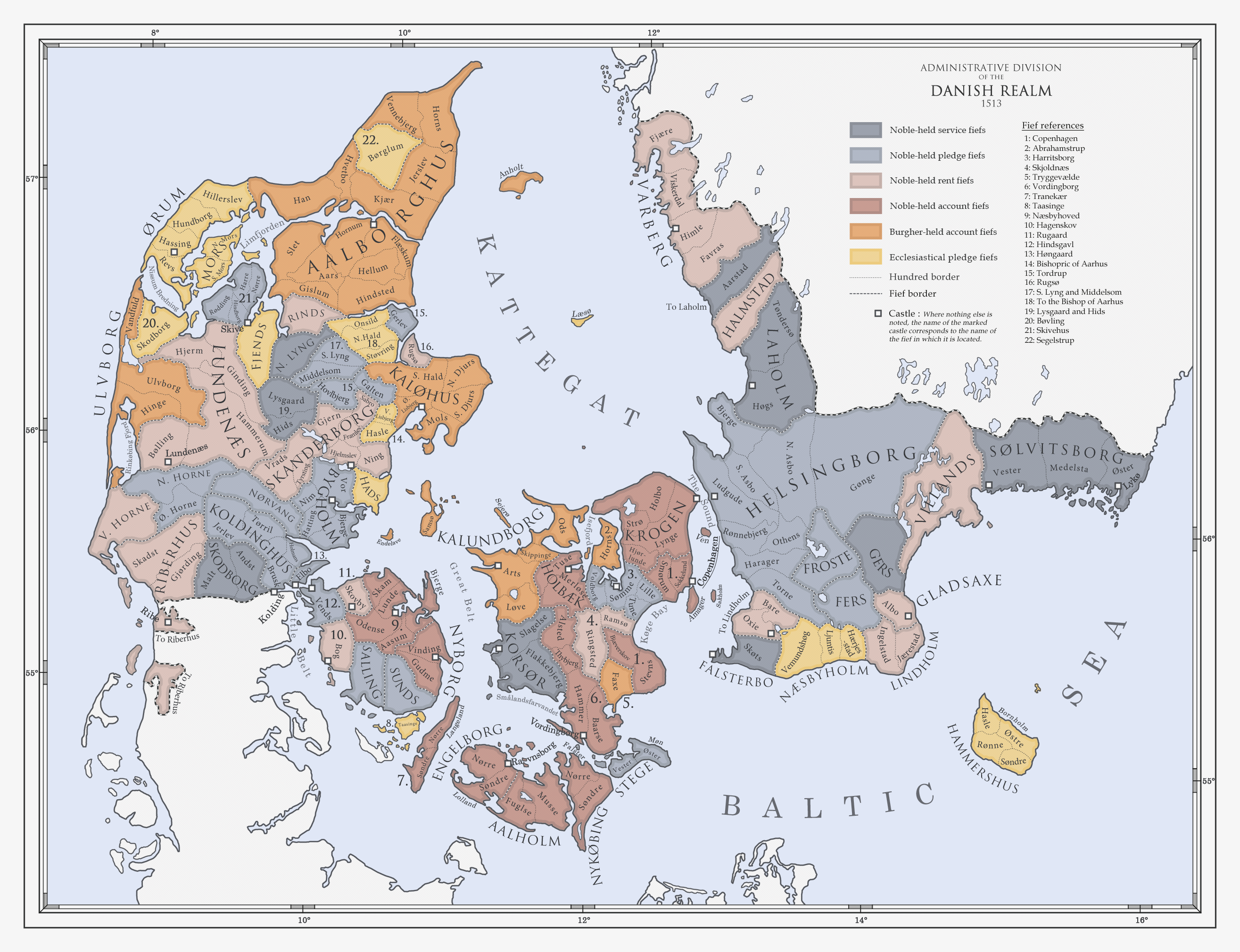

Danish fiefs and hundreds at the time of Christian II's ascension.

All land not owned directly by the aristocracy and the church belonged to the Danish feudal system. Although inherently feudal in nature, they were not as a rule passed on within certain families, but enfeoffed as a result of a tangible service rendered by a nobleman. Fiefs consisted of an amalgamation of lesser administrative divisions known as hundreds (corresponding to shires in England) and were enfeoffed on vastly different terms - the only commonality being the fief-holder’s obligation to supply military forces when called upon by the monarch

[8]. Generally speaking the various fiefs fell into four broad categories:

- The account fief: the most profitable arrangement for the crown. The fief-holder served as a royal appointed official who received a previously agreed upon salary in exchange for his service.

- The rent fief: the second-most profitable enfeoffment for the crown. A certain rent was placed on the fief’s revenue which was paid directly into the royal coffers, whilst the fief-holder retained the remaining surplus in exchange for his services.

- The pledge fief: usually granted in exchange for a loan provided by the fief-holder. In place of paying an interest rate, the crown pledged the income of the fief to the creditor until the debt had been paid.

- The service fief: the least profitable enfeoffment for the crown as the only compensation provided the royal treasury was the military service of the fief-holder, who otherwise kept all the revenue gathered in the fief for himself.

However, the most worrisome demand by the councilar opposition was the enlargement of their jus resistendi - their right to resist a prince governing against his promises and the stipulations of his accession charter. A comparative article had been present in king Hans’ charter, but it had been vague and self-contradictory. Under the constitutional guidance of archbishop Gunnersen, the council of the realm now demanded that the king promised:

”…at holde thenne wor recess, som wii Danmarkis oc Noriges indbyggere swærge skulle, […], swo well som indbyffer skulle wære plictug at holde oss huldskab oc mandskab, oc gøire wii emodt forschreffne wor recess oc wele ingelunde lade oss vnderwise thervti aff riighens radh, […] tha skulle alle riighens indbyggere wedt theris ere troligen tilhielpe thet at affwærge oc inthet ther met forbryde emodt then eedh oc mandskab, som the oss giøre skulle.”

“... to uphold this charter, which we have sworn the inhabitants of Denmark and Norway [...] likewise the inhabitants shall pledge us their loyalty and fidelity, but should we act against this charter and not allow ourselves to be rightly guided by the council of the realm [...] then all the inhabitants of the realm shall be honour-bound to prevent it[9] and in doing so shall not break the vow of loyalty and fidelity which they have us so sworn.”

In effect this right to rebellion legalized armed uprisings by the nobility against the crown, if the monarch violated any of the many articles in his accession charter. However, the article had some serious flaws, as it did not stipulate which institution should be the judge of exactly what constituted a breach of the charter. This had been the case of Alvsson’s rebellion, where the tentative legality of the uprising was crushed by the sheer force of king Hans’ troops. In a political reality without institutional restraints, the only judge was raw unmitigated military power.

Nevertheless, Christian was presented with a fait-accompli. Accept the charter or face the prospect of civil war against the council and a possible pretender. Chaos in Denmark would leave the flood-gates open and likely mean the damnation of the three state union, the golden calf of the House of Oldenburg. Thus, Christian had little to no choice. The council had the constitutional high-ground and if he were to advance the cause of the crown, he would, at any rate, first have to wear it. With his scribes, squires and friends around him, the prince agreed to the radical stipulations

[10] of the charter, and affixed his seal to the document above those of 29 Danish and 7 Norwegian councillors. On the 22nd of July 1513, five months and two days after the death of his father, the matter of the succession had finally been settled.

The Swedish delegates, however, had made excuses and pleaded that their orders from Stockholm had not included instructions as to how to act in relation to drawing up an accession charter.

Still, the prince was now the legally elected king of Denmark and Norway, rightfully chosen king of Sweden, king of the Wends and the Goths, Duke of Schleswig, Holstein and Stormarn as well as Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst - the issue of the Swedish succession would have to be postponed for the immediate future.

He needed to be crowned.

And he needed a wife.

Footnotes:

[1]As happened OTL.

[2]The English translation of the name of the noble house of Bille. Jönsson derogatorily referring to them as “those Beetles” is a bit of poetic license on the translation on my part.

[3]The king’s good looks were often noted in OTL, even by the likes such as Albrecht Dürer.

[4]As in OTL. According to one historian, “... there hardly was a single soul amongst the commoners in the entire realm who wished for another successor to king Hans.”

[5]The exact nature of this plot is somewhat disputed, but it is certain that a fraction within the aristocracy wished to reject the king’s son and take his uncle for their king.

[6]Gunnersen was a fascinating person. He led a vicious feud with the Scanian nobility which culminated in the killing of the Steward of the Realm, Poul Laxmand (if you played Denmark in EU IV, you might have seen an event relating to this murder).

[7]One of the first divergences, although not a major one. Even in OTL, Christian was remarkably pliable during the 1513 negotiations. ITTL, he has surrounded himself with noble friends and allies such as the Bille and Gøye families. However, commoners will continue to play a prominent part in Christian’s government, as will be expanded upon later.

[8]The so-called rostjeneste (horse-service)

[9]“It” meaning the continued rule of the king.

[10]Besides the inclusion of the “right of resistance” the charter included 68 articles, a considerable enlargement of the 51 articles found in the charter of king Hans.