You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

To be a Fox and a Lion - A Different Nordic Renaissance

- Thread starter Milites

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 37 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 26: White Rose Victorious Chapter 27: The One Good Harvest Map of Denmark and Schleswig at the End of the Late Medieval Period (ca. 1490-1513) Chapter 28: On the Shores of a Restless Sea Chapter 29: A Thorny Olive Branch Chapter 30: Via Media Chapter 31: The Garefowl Feud Chapter 32: The Queen of the Eastern SeaThe main difference between Regent and Viceroy is actually permanence. Regent's are appointed if the need is seen to be for a limited time, Viceroy's if it is expected to be an ongoing office. Other term's sometimes used in this period are Guardian ( tended to be if a General was needed more than an administrator ) or Lord Lieutenant ( literally a Lord standing in place of the King ).A direct translation of Riksföreståndare would be something like Royal Representative, Regent or Viceroy, the latter of the three probably works best in this context. That said, either of BlueFlowwer's suggestions could work as well. I have even seen some translate it as Royal Governor, but there are English language conotations which don't really work in this case.

Thanks guys, I'm considering using Lord Steward of the Realm or just the Lord Steward for short.

Is there any other

I meant that he flaunted it as in:

2: to treat contemptuously

There is a wierd bit of family lore in my family which states that one of my ancestors was the person charged with planning out the details of the Stockholm Bloodbath. Always a great way to introduce yourself to Swedes

Is there any other

You say he flaunted his accession charter. did you mean that he flouted it?

I meant that he flaunted it as in:

2: to treat contemptuously

- flaunted the rules

First update should be along before too long.

The notion of the union being a dead man walking after 1434/1448 has actually been challenged in recent years. All the way until the Vasa rebellion, the union was seen as the given political framework. Ture Jönsson of the House of Three Roses (with whom we'll be further acquainted in the first update) actually wrote the Lord Regent Sten Sture the Younger in 1513, and commented that after the death of king Hans, it was his that "... these three realms be ruled by a man born in this realm and not always by Danish men..." This shows that the union as a continued institution was very much alive within the Swedish political elite at the very end of its lifespan and that it was even considered plausible for the crown to wander between its constituent realms.

I honestly don't know how much I agree with this analysis though, but no matter which way the Kalmar Union wanders, I can promise you that plausibility shall be my battle cry

The main problem for Christian is not that the Union is not an established concept - it is, and there will be plenty of Swedish noblemen that will support the Union, especially if it is in their own private interests.

The problem is that Sweden adds nothing but prestige to the Danish crown. Every Danish King have to either negotiate and give up even more power (as Christian did OTL and ITTL, even agreeing that the Swedes had the right to revolt) even further decentralising the realm or fight local noblemen that thought they could gain something from independence (mostly better positions and more power for themselves) which were almost always supported by the powerful Swedish peasants (who had the real military power in Sweden in this era through their peasant militias) since they were more afraid of ending up in semi-serfdom like the Danish peasants than death or hell itself.

Sweden is so decentralised in this era that the Danish crown will always need to spend much more resources to keep Sweden under control than it can possibly gain from owning Sweden - and it has been this way ever since Bo Jonsson (Grip)s life-long crusade to reduce the power of the Crown in Sweden, which was what weakened Sweden enough for it to spend the next 200 years in more or less constant civil war. This is what needs fixing, and a foreign King centralising power and resources will meet resistance and probably revolt from both the Swedish nobility and the Swedish peasants. And the Hansa, wary of the Oldenburg ambitions in northern Germany and a strong Danish royal power able to enforce Hansaetic payments for trade and fishing rights (like Valdemar Atterdag subjected Visby to) will probably support Swedish revolts - even without Christian supporting Dutch merchants over Hansaetic ones.

And that is not even considering that the strong Danish nobility which will also resent any centralisation efforts by Christian - even without Sigbrit to place all the blame on.

Personally, I think this era is too late to save the Kalmar Union. Denmark can stunt Sweden's development and become the primary power of the Baltic, but not really preserve the Kalmar Union. The social, geopolitical and economic differences are too great. BUt you may of course be of a different opinion. Should you want some hints at what I think are the main issues and perhaps how to adress them, I would be happy to oblige.

The problem is that Sweden adds nothing but prestige to the Danish crown. Every Danish King have to either negotiate and give up even more power (as Christian did OTL and ITTL, even agreeing that the Swedes had the right to revolt) even further decentralising the realm or fight local noblemen that thought they could gain something from independence (mostly better positions and more power for themselves) which were almost always supported by the powerful Swedish peasants (who had the real military power in Sweden in this era through their peasant militias) since they were more afraid of ending up in semi-serfdom like the Danish peasants than death or hell itself.

I don't think I necessarily share your opinion that Sweden added nothing but prestige to the union monarchs, even though I fully agree that it seems that way today. Sweden was an important link in Christian's OTL grand plans for a Scandinavian trading company, which was to be created as a bulwark against Hanseatic influence in concert with the Netherlandish trading cities, and by securing these commercial access points, the crown hoped to curb the meddling of Lübeck in Nordic politics. An interesting point is that Christian for all his Machiavellian manoeuvring vis-a-vis the high nobility, actually strove to better the plight of the peasantry. His ambitious legal reforms included a passage which stipulated that:

"... slig og ukristelig sædvane, som hertil i Sjælland, Falster, Laaland og Møen været haver med stakkels bønder og kristne mennesker at sælge og bortgive ligesom andre uskellige kreatur, skal ej efter denne dag saa ydermere ske, men naar deres husbond og herskab farer uredeligt med dem og gør dem nogen uret og ubod, da maa de flytte af det gods, de paasidder, og ind på en andens gods, som bønder gør i Skaane, Fyen og Jylland."

"... such an unchristian practice which is present on Zealand, Falster, Laaland and Møen, where poor peasants and Christian people have been sold and awarded to others like common cattle, shall after this day never be permitted to happen again, and if their lord and master treats them unjustly and inflict upon them wrongful grievances, then they shall be permitted to move to another [nobleman's] estate, such as peasants do in Scania, Funen and Jutland." (My own translation).

Now, the Law of the Land and Cities was not written for the sake of the third estate's bright eyes, but as a way to further the process of state-building and centralisation. However, is it possible that combined with the promises Christian II made in OTL towards the commoners of Sweden that he could sway them to his side? Supposing that a good deal of the OTL events were butterflied away?

Sweden is so decentralised in this era that the Danish crown will always need to spend much more resources to keep Sweden under control than it can possibly gain from owning Sweden - and it has been this way ever since Bo Jonsson (Grip)s life-long crusade to reduce the power of the Crown in Sweden, which was what weakened Sweden enough for it to spend the next 200 years in more or less constant civil war. This is what needs fixing, and a foreign King centralising power and resources will meet resistance and probably revolt from both the Swedish nobility and the Swedish peasants. And the Hansa, wary of the Oldenburg ambitions in northern Germany and a strong Danish royal power able to enforce Hansaetic payments for trade and fishing rights (like Valdemar Atterdag subjected Visby to) will probably support Swedish revolts - even without Christian supporting Dutch merchants over Hansaetic ones.

First let me stress that Christian is still ITTL a proponent of promoting Dutch traders as a way to balance against the power of the Hanse, though he's less "radical" in his approach when compared to OTL. Secondly, I agree that the decentralised nature of Swedish late medieval society is a daunting issue, which will need to be addressed. However, even in our time, Christian II's diplomacy managed to compel the Hanse into enforcing a blockade of the rebellious Swedes, which in effect greatly aided (if not decided) the campaign of 1520 in favour of the king. Conversely, it was the renewed support from Lübeck that turned out to be the deciding factor in the Vasa revolt. So yeah, lot's of interesting aspects to investigate, I do hope you'll keep up your commentary!

And that is not even considering that the strong Danish nobility which will also resent any centralisation efforts by Christian - even without Sigbrit to place all the blame on.

Even in our time, the nobility of Denmark was not a monolithic entity. There was some not insignificant support for the king's programme with the immensely wealthy Mogens Gøye being the most prominent of the royal supporters. This "progressive" (and I'm using that word very cautiously!) faction within the aristocracy understood and supported a revision of the social order and sought to assume the role of a partnership of sorts with the monarchy. A system of centralisation with noble characteristics, if you will. In effect, what broke Christian's rule was the fact that he proceeded with his plans too rashly and forcefully, which resulted in all his enemies coming at him at the very same time.

Personally, I think this era is too late to save the Kalmar Union. Denmark can stunt Sweden's development and become the primary power of the Baltic, but not really preserve the Kalmar Union. The social, geopolitical and economic differences are too great. BUt you may of course be of a different opinion. Should you want some hints at what I think are the main issues and perhaps how to adress them, I would be happy to oblige.

I have a general outline of events planned out for about 1530, but after that I'm somewhat in the dark. I do not, however, believe that an initially successful conquest like in OTl combined with a different set of post-conquest events (if Christian even manages that!) would result in a centralised proto-absolutist united monarchy, but neither do I see the union as necessarily doomed. The trick is to walk that tightrope convincingly and find a plausible path for the union to develop without the presence of OTL's events (which is difficult, considering how positively massive those were for the course of Scandinavian history!). In that regard, and generally speaking, I would love to hear your input!

@von Adler have a very good point of Sweden not having delivered much to the union. But let's look at the benefit with a continued union.

1: The Danish king may have to continue deal with the trouble which are Sweden, but we avoid the Danish-Swedish wars, which was far more detructive

2: a non-independent Sweden ensure the Danish king can upkeep a control over the Baltic

That's the benefit if nothing change.

Next we have to look what did happen in the 16th century and how will it affect the union. Here I expect that Christian II will convert to Lutheranism the benefits are to big to not do it and it's hard to imagine the Union will avoid a religious war if he doesn't convert.

This free up the massive estates, these can be used to bribes, but will also create a much more massive crown domain, and will enable him to give te nobility land in the different states. If Swedish nobility who have land in north Jutland would have interest in supporting a continued union, Danish nobility who have land in Närke would support the king keeping the union together.

Next if the king increase the amount of crown domains, he could limit the state's finances to taxation in these plus tariff, customs, taxation of urban areas etc. leaving the nobility and free peasantry free of taxation. This wouldn't be viable in the long term, but it would give the king a century to one and half of quiet, which would give him time to establish a strong central power and a army. Yes this will mean that Sweden won't be especially valuable for the king, but honestly not having to deal with the Vasa would be worth it, and if we look historical the four most valuable Swedish province under the Swedish imperial area was Livonia, Estonia, Scania and Bremen-Verden (with Livonia being the far most valuable giving from my memory something like half of the Swedish state budget). As such with Sweden being quiet the Danish king can start wars in Baltic, he already have a casus belli for Estonia which he can use to take all three duchies.

1: The Danish king may have to continue deal with the trouble which are Sweden, but we avoid the Danish-Swedish wars, which was far more detructive

2: a non-independent Sweden ensure the Danish king can upkeep a control over the Baltic

That's the benefit if nothing change.

Next we have to look what did happen in the 16th century and how will it affect the union. Here I expect that Christian II will convert to Lutheranism the benefits are to big to not do it and it's hard to imagine the Union will avoid a religious war if he doesn't convert.

This free up the massive estates, these can be used to bribes, but will also create a much more massive crown domain, and will enable him to give te nobility land in the different states. If Swedish nobility who have land in north Jutland would have interest in supporting a continued union, Danish nobility who have land in Närke would support the king keeping the union together.

Next if the king increase the amount of crown domains, he could limit the state's finances to taxation in these plus tariff, customs, taxation of urban areas etc. leaving the nobility and free peasantry free of taxation. This wouldn't be viable in the long term, but it would give the king a century to one and half of quiet, which would give him time to establish a strong central power and a army. Yes this will mean that Sweden won't be especially valuable for the king, but honestly not having to deal with the Vasa would be worth it, and if we look historical the four most valuable Swedish province under the Swedish imperial area was Livonia, Estonia, Scania and Bremen-Verden (with Livonia being the far most valuable giving from my memory something like half of the Swedish state budget). As such with Sweden being quiet the Danish king can start wars in Baltic, he already have a casus belli for Estonia which he can use to take all three duchies.

@Milites

Allowing the serfs a moving week is a far cry from what the Swedish peasants had - representation at the things and the estates parliament that started to replace them in this era, owning around 50% of the arable land in the country, holding economic and military power to keep it that way. A consistent problem for the Danes in Sweden was that the Swedish nobility pilfered everything if placed as tax collectors, and the Danish, German and Frisian (the latter two mercenary captains) tax collectors installed treate the peasants like the unarmed serfs they were used to back home, and usually thought their position was a reward for service, with the unspoken argreement that anything they could press from the peasants beyond what was owed to the Crown, they could keep. A new peasant revolt was usually the result - several times the Swedish peasants revolted on their own accord, placing the Swedish nobility on the backfoot and scrambling to either join or oppose them.

And the Swedish peasants proved strong enough to take on strong Danish armies on several occassions - Brunkeberg 1471, Brunnbäck and VÄsterås 1521.

The Hansa controls the salt trade from Lüneburg, and any Danish conflict with the Hansa is going to result in shortages of salt and huge price spikes due to a Hansaetic blockade. And the Swedish peasants will suffer, and probably revolt, and Lübeck and other Hansaetic cities will then support them.

Sweden and Denmark has no common enemies in this era - Sweden fears Novgorod/Russia and its eastern border, while the Danes have trouble with the Hansaetic cities and the Oldenburgian ambitions in northern Germany. Danish peasants have little economical, political or military power, while Swedish peasants have all three and are very well prepared to fight for them. One needs to remember that Gustav Eriksson (Vasa) faced a multitude of revolts and rebellions during his reign - the Dacke feud was just the biggest and most successful. The Swedes are used to revolting and getting what they want from it during this era, and any royal power, be it Danish or local Swedish, will have to deal with that during this era.

The social differences between Denmark and Sweden can clearly be seen by the land ownership:

Country-Crown-Freeholding peasants-Nobility-Church (roughly 1400-1500)

Sweden-6-52-21-21.

Denmark-10-15-38-37.

Norway-7-37-15-41.

Finland-4,5-90-3-2,5.

In a sense, I think the Sound toll was a distaster disguised as a blessing for the Danes - with the ready source of real coin, the pressure to create a strong administration and an effective bureaucracy to maximise tax and manpower did not exist for Denmark the same way it did for Sweden.

Allowing the serfs a moving week is a far cry from what the Swedish peasants had - representation at the things and the estates parliament that started to replace them in this era, owning around 50% of the arable land in the country, holding economic and military power to keep it that way. A consistent problem for the Danes in Sweden was that the Swedish nobility pilfered everything if placed as tax collectors, and the Danish, German and Frisian (the latter two mercenary captains) tax collectors installed treate the peasants like the unarmed serfs they were used to back home, and usually thought their position was a reward for service, with the unspoken argreement that anything they could press from the peasants beyond what was owed to the Crown, they could keep. A new peasant revolt was usually the result - several times the Swedish peasants revolted on their own accord, placing the Swedish nobility on the backfoot and scrambling to either join or oppose them.

And the Swedish peasants proved strong enough to take on strong Danish armies on several occassions - Brunkeberg 1471, Brunnbäck and VÄsterås 1521.

The Hansa controls the salt trade from Lüneburg, and any Danish conflict with the Hansa is going to result in shortages of salt and huge price spikes due to a Hansaetic blockade. And the Swedish peasants will suffer, and probably revolt, and Lübeck and other Hansaetic cities will then support them.

Sweden and Denmark has no common enemies in this era - Sweden fears Novgorod/Russia and its eastern border, while the Danes have trouble with the Hansaetic cities and the Oldenburgian ambitions in northern Germany. Danish peasants have little economical, political or military power, while Swedish peasants have all three and are very well prepared to fight for them. One needs to remember that Gustav Eriksson (Vasa) faced a multitude of revolts and rebellions during his reign - the Dacke feud was just the biggest and most successful. The Swedes are used to revolting and getting what they want from it during this era, and any royal power, be it Danish or local Swedish, will have to deal with that during this era.

The social differences between Denmark and Sweden can clearly be seen by the land ownership:

Country-Crown-Freeholding peasants-Nobility-Church (roughly 1400-1500)

Sweden-6-52-21-21.

Denmark-10-15-38-37.

Norway-7-37-15-41.

Finland-4,5-90-3-2,5.

In a sense, I think the Sound toll was a distaster disguised as a blessing for the Danes - with the ready source of real coin, the pressure to create a strong administration and an effective bureaucracy to maximise tax and manpower did not exist for Denmark the same way it did for Sweden.

Allowing the serfs a moving week is a far cry from what the Swedish peasants had - representation at the things and the estates parliament that started to replace them in this era, owning around 50% of the arable land in the country, holding economic and military power to keep it that way. A consistent problem for the Danes in Sweden was that the Swedish nobility pilfered everything if placed as tax collectors, and the Danish, German and Frisian (the latter two mercenary captains) tax collectors installed treate the peasants like the unarmed serfs they were used to back home, and usually thought their position was a reward for service, with the unspoken agreement that anything they could press from the peasants beyond what was owed to the Crown, they could keep. A new peasant revolt was usually the result - several times the Swedish peasants revolted on their own accord, placing the Swedish nobility on the backfoot and scrambling to either join or oppose them.

Potentially these could help solve each other. Christian was, in his own way, someone who tried to be a king of the people. IOTL the favor he showed Sigbrit Villoms led to the middle class starting to compete with the nobility in Christian's court, sowing conflict between Christian and the nobility. ITTL we've already seen that Christian is relying on forging a noble coalition of his supporters. This could already ramp down a bit on his conflicts with the nobility, and without an easy outlet of supporting the lower classes with Sigbrit he'll likely try other methods of helping the peasantry.In a sense, I think the Sound toll was a distaster disguised as a blessing for the Danes - with the ready source of real coin, the pressure to create a strong administration and an effective bureaucracy to maximise tax and manpower did not exist for Denmark the same way it did for Sweden.

If the trend was for the Swedish peasants to start rebellions over abuses of tax collectors or fears of their rights and powers being infringed upon by centralization, it is like to break out at some point. If Christian is in a stronger position with the nobility at the time, the Swedish nobility might side with Christian. Without the nobility to be perceived as the leaders, it is a clear peasant rebellion which could attract Christian's attention if he still wants to portray himself as a king of the people. It could bring a great deal of royal attention to a critical issue. Even a few concessions to the Swedish peasantry directly could have major effects. I'm pretty sure previous agreements had already been made throughout the Kalmar Union that 'foreigners' couldn't be appointed as officials in Sweden, but I'm pretty sure they were later renegaded on. Christian actually attempting to stick to such a promise to curry favor with the lower classes could force him in an interesting direction with your post basically saying foreigners and even Swedish nobility couldn't be trusted as tax collectors doesn't leave many options.

The title actually notes the Renaissance, and while potentially merely a reference to the period, it could actually hint at the Nordic countries developing differently in this era of political, literary, economic development beyond changes in the Kalmar Union. Professional bureaucracies and administrations were already forming throughout Europe by this time. Christian could attempt to create a low level tax collection bureaucracy, in essence doing away with tax farming. I'm not sure how the political, military, and economic power of the Swedish peasantry correlated to literacy and organization but the peasants themselves could play a major role in such a bureaucracy. If they don't have the skills necessary, it could lead to Christian promoting education and literacy in the lower classes. Establishing universities or other educational organizations to create the educated and literate populace to serve as a pool for professional clerks. It's not too early, since I'm pretty sure in 1570 just half a century later Sweden established church laws that resulted in all town dwellers needing to be taught to read. This would allow Christian to help the lower classes, while not directly infringing on the top level political power of the nobility his OTL affiliation with Sigbrit did. It would also make a huge difference in the overall Nordic Renaissance, since I know Norway didn't have a university until the early 19th century. So even if this is more a Swedish system based around the privileges he grants to the Swedish peasantry, it could very easily spread to Denmark and Norway (especially if the union remains). Meanwhile if he actually follows through with such promises, the Swedish peasantry could start to think that a distant king in Denmark is preferable to one trying to establish power in Sweden itself (which the Vasa dynasty did). With the peasantry on his side, the Swedish nobility lose a major base for seceding.

Is that at all reasonable, or am I missing something crucial about the circumstances and thinking of the time?

Lubeck dominated the salt trade, but it wasn't the only provider. Lubeck, and the overall Hansa, started to decline when Dutch merchants started bringing cheaper salt from France to the Baltic (among other things). Novgorod also had several areas of saltworks, and Moscow has already ended the Hanseatic Kontor in Novgorod. Luneburg salt is no doubt still cheaper in this time, but if Christian faces less domestic opposition and starts extending trading ties for his 'Scandinavian trade company' it could only force these secondary salt trades to increase in importance.The Hansa controls the salt trade from Lüneburg, and any Danish conflict with the Hansa is going to result in shortages of salt and huge price spikes due to a Hansaetic blockade. And the Swedish peasants will suffer, and probably revolt, and Lübeck and other Hansaetic cities will then support them.

Not saying it will happen. It would rely on Christian being able to develop these secondary sources quickly enough, but starting an embargo on salt to Sweden doesn't automatically mean victory. Especially since that's already a card that has been played before, so given internal peace it's something that could be prepared for.

Almost done writing Chapter 2. Should be posted before the end of the week

I'm not implying at all that the societal position of the Danish and Swedish peasantry were equal. Far from it. However, I do use the example of Christian II's legal reforms to demonstrate his willingness to promote the rights of the lower estates vis-a-vis the nobility.

The Swedish commoners' armies were indeed a powerful force, and as you say, they even forced the hand of the higher estates from time to time (as the Engelbrekt rebellion goes to show). However, they were beaten and sometimes even decisively. However, I'm curious as to what made Gustav Vasa succeed in OTL in combating the numerous peasant risings against him (IIRC, they were pretty much near yearly events for most of his reign).

Regarding the Sound Due, I don't think I quite understand your position, although I must admit that I find it quite novel! Centralisation was the holy grail of the monarchy ever since the interregnum of the 1300s. However, domestic politics in the form of the strong councilar aristocracy, who jealously guarded their privileges through the accession charters, were the main obstacle. Some of the hindrances were removed through the secularisation of church holdings during the Reformation, but it was only truly accomplished by the absolutist coup d'etat in 1660. The Due was an incredible important source of income for the crown and gave it the muscle it needed to confront the aristocracy politically, but even Christian IV was threatened with the prospect of rebellion when he attempted to start a war with Sweden without the approval of the council of the realm. In short, what I'm trying to say is that I think the reasons for lacking centralisation and state-building in early modern Denmark/Norway should be found in the domestic constitutional framework. Which funnily enough traces its origin to the deposal of Christian II.

Allowing the serfs a moving week is a far cry from what the Swedish peasants had - representation at the things and the estates parliament that started to replace them in this era, owning around 50% of the arable land in the country, holding economic and military power to keep it that way. A consistent problem for the Danes in Sweden was that the Swedish nobility pilfered everything if placed as tax collectors, and the Danish, German and Frisian (the latter two mercenary captains) tax collectors installed treate the peasants like the unarmed serfs they were used to back home, and usually thought their position was a reward for service, with the unspoken argreement that anything they could press from the peasants beyond what was owed to the Crown, they could keep. A new peasant revolt was usually the result - several times the Swedish peasants revolted on their own accord, placing the Swedish nobility on the backfoot and scrambling to either join or oppose them.

And the Swedish peasants proved strong enough to take on strong Danish armies on several occassions - Brunkeberg 1471, Brunnbäck and VÄsterås 1521.

The Hansa controls the salt trade from Lüneburg, and any Danish conflict with the Hansa is going to result in shortages of salt and huge price spikes due to a Hansaetic blockade. And the Swedish peasants will suffer, and probably revolt, and Lübeck and other Hansaetic cities will then support them.

Sweden and Denmark has no common enemies in this era - Sweden fears Novgorod/Russia and its eastern border, while the Danes have trouble with the Hansaetic cities and the Oldenburgian ambitions in northern Germany. Danish peasants have little economical, political or military power, while Swedish peasants have all three and are very well prepared to fight for them. One needs to remember that Gustav Eriksson (Vasa) faced a multitude of revolts and rebellions during his reign - the Dacke feud was just the biggest and most successful. The Swedes are used to revolting and getting what they want from it during this era, and any royal power, be it Danish or local Swedish, will have to deal with that during this era.

The social differences between Denmark and Sweden can clearly be seen by the land ownership:

Country-Crown-Freeholding peasants-Nobility-Church (roughly 1400-1500)

Sweden-6-52-21-21.

Denmark-10-15-38-37.

Norway-7-37-15-41.

Finland-4,5-90-3-2,5.

In a sense, I think the Sound toll was a distaster disguised as a blessing for the Danes - with the ready source of real coin, the pressure to create a strong administration and an effective bureaucracy to maximise tax and manpower did not exist for Denmark the same way it did for Sweden.

I'm not implying at all that the societal position of the Danish and Swedish peasantry were equal. Far from it. However, I do use the example of Christian II's legal reforms to demonstrate his willingness to promote the rights of the lower estates vis-a-vis the nobility.

The Swedish commoners' armies were indeed a powerful force, and as you say, they even forced the hand of the higher estates from time to time (as the Engelbrekt rebellion goes to show). However, they were beaten and sometimes even decisively. However, I'm curious as to what made Gustav Vasa succeed in OTL in combating the numerous peasant risings against him (IIRC, they were pretty much near yearly events for most of his reign).

Regarding the Sound Due, I don't think I quite understand your position, although I must admit that I find it quite novel! Centralisation was the holy grail of the monarchy ever since the interregnum of the 1300s. However, domestic politics in the form of the strong councilar aristocracy, who jealously guarded their privileges through the accession charters, were the main obstacle. Some of the hindrances were removed through the secularisation of church holdings during the Reformation, but it was only truly accomplished by the absolutist coup d'etat in 1660. The Due was an incredible important source of income for the crown and gave it the muscle it needed to confront the aristocracy politically, but even Christian IV was threatened with the prospect of rebellion when he attempted to start a war with Sweden without the approval of the council of the realm. In short, what I'm trying to say is that I think the reasons for lacking centralisation and state-building in early modern Denmark/Norway should be found in the domestic constitutional framework. Which funnily enough traces its origin to the deposal of Christian II.

Almost done writing Chapter 2. Should be posted before the end of the week

I'm not implying at all that the societal position of the Danish and Swedish peasantry were equal. Far from it. However, I do use the example of Christian II's legal reforms to demonstrate his willingness to promote the rights of the lower estates vis-a-vis the nobility.

The Swedish commoners' armies were indeed a powerful force, and as you say, they even forced the hand of the higher estates from time to time (as the Engelbrekt rebellion goes to show). However, they were beaten and sometimes even decisively. However, I'm curious as to what made Gustav Vasa succeed in OTL in combating the numerous peasant risings against him (IIRC, they were pretty much near yearly events for most of his reign).

Regarding the Sound Due, I don't think I quite understand your position, although I must admit that I find it quite novel! Centralisation was the holy grail of the monarchy ever since the interregnum of the 1300s. However, domestic politics in the form of the strong councilar aristocracy, who jealously guarded their privileges through the accession charters, were the main obstacle. Some of the hindrances were removed through the secularisation of church holdings during the Reformation, but it was only truly accomplished by the absolutist coup d'etat in 1660. The Due was an incredible important source of income for the crown and gave it the muscle it needed to confront the aristocracy politically, but even Christian IV was threatened with the prospect of rebellion when he attempted to start a war with Sweden without the approval of the council of the realm. In short, what I'm trying to say is that I think the reasons for lacking centralisation and state-building in early modern Denmark/Norway should be found in the domestic constitutional framework. Which funnily enough traces its origin to the deposal of Christian II.

Gustav Eriksson (Vasa) was a superb administrator and a very shrewd diplomat and knew how to use it to his advantage to deal with revolts and risings. Twice he went to Dalarna to speak to the peasants himself when they rose, adressing their grievances and calming them.

When the Lords of Västergötland rose 1529 and the peasants of Småland rose in support, taking his sister hostage, he sent them a letter thanking them for protecting his sister against wile traitors and rebels, giving the peasants a convenient out when he outmanouvred the Västgöta Lords from their supporters.

He was shrewd, he was close at hand and could intervene personally at several occassions and he understood the mentality and culture of the Swedish peasants and how to deal with them much better than the Danish Kings did.

It also helped that Christian had killed off most of the potential rivals in Sweden when he executed most of the independence party noblemen at the bloodbath of Stockholm 1520. The revolts lacked serious candidates to rally behind, and Denmark was unable to use them to restore the Union as it was embroiled in the Count's feud at the time.

As for the sound toll being a net negative, I can see why it would be surprising, but I still hold that because of it, the Danish state never had the same pressure to reform as the Swedish one did. Swedish Kibgs could ally with the peasants to roll back the dominance and land ownership of the nobility to increase centralisation, domestic production and create a very good army in a way that Denmark never did.

As for the sound toll being a net negative, I can see why it would be surprising, but I still hold that because of it, the Danish state never had the same pressure to reform as the Swedish one did. Swedish Kibgs could ally with the peasants to roll back the dominance and land ownership of the nobility to increase centralisation, domestic production and create a very good army in a way that Denmark never did.

I agree with this, but it was mainly a long term problem, in the short term a alternate source of income enable the king to finance the state while avoiding raising taxes on the landowners. Christian II have some benefit, he can use the Reformation to strengthen the central power and union, the increasing weakness of the Hanseatic League enable him to finally dominate the Baltic. The Reformation also enable to target the Livonian Knights domains, and I suspect that the Swedish estates would be pretty positive toward this.

Chapter 2: With Her Gaze Forever upon His Grace

Chapter 2

With Her Gaze Forever upon His Grace

“It is a virtuous and beautiful princess Your Grace has wooed. She has taken Your Grace fully to heart and never takes her eyes off Your Grace’s portrait… she is noble, wise and skilled and is thought sweet and pretty by all of Your Grace’s servants.”

- Erik Valkendorf, 1515

With Her Gaze Forever upon His Grace

“It is a virtuous and beautiful princess Your Grace has wooed. She has taken Your Grace fully to heart and never takes her eyes off Your Grace’s portrait… she is noble, wise and skilled and is thought sweet and pretty by all of Your Grace’s servants.”

- Erik Valkendorf, 1515

Bella gerant alii, tu felix Austria nube

Nam quae Mars aliis, dat tibi regna Venus

Let others only war, but you happy Austria, marry!

For the realms bequeathed to others by Mars, you shall receive from Venus

- Latin couplet, ca. 1500

By all accounts the new king of Denmark and Norway was a tall and handsome man. In 1513 he was 32 years old, with a fierce bifurcated beard which grew in redder than his shoulder-long auburn hair, a feature which, according to some foreign dignitaries, made him look “... like an unruly barbarian king.”[1] However, besides being the heir to one of the largest state conglomerates in all of Europe, he had been educated in the classics and statesmanship as well as the art of war. He was an accomplished jouster and hunter and to these skills he added a considerable interest in both religion and the humanist teachings of Erasmus. Furthermore, he had commanded armies on behalf of his father and conducted military campaigns before taking on the duties of viceroy in Norway. Thus he was, by all standards, quite the catch.

Consequently, gossiping had permeated the subject of the prince’s marriage for years. In 1493, a wild rumour had spread through Sweden that Christian was to marry the daughter of the grand prince of Muscovy, Ivan III, in exchange for the surrender of Finland to the Russians. To these speculations, king Hans was said to have wryly remarked that “... he certainly hoped that he needn’t purchase his son a bride.” Some years later, an earnest attempt by the grand duke to secure a marriage alliance through the betrothal of one of his daughters to the heir to the North did seem to have been made though. Such an alliance would have been combined with the wedding of Ivan’s son and successor Vasili[2] to Hans’ daughter Elizabeth. However, nothing came of the Russian proposal, as the rapprochement with Muscowy had primarily been made in order to frighten (which it certainly did) the unruly Swedish aristocratic caretaker government.

Other rumours had the prince promised to the youngest daughter of Henry VII of England, Mary, the later queen of France, but these too proved to be unfounded. Only in 1505 did king Hans put serious effort into finding his son a suitable match when he approached his old ally Louis XII of France through the intermission of his nephew, James IV of Scotland. The Oldenburg king proposed a match between Christian and Anna de la Tour, the daughter of the Count of Auvergne and a relative of the French queen. However, by the time the Danish embassy arrived, the countess had already been married off to the Scottish Duke of Albany, John Stewart.

King Christian II of Denmark, Norway and Sweden by Michael Sittow, ca. 1515. A painter from Tallinn, Sittow worked for most of his life as the court painter of Isabella of Castille, the wife of Ferdinand II of Aragon.

However, the French queen Anne[3] seems to have been genuinely disappointed that the marriage fell through and as such hastened to propose that Anna’s younger sister Madeleine[4] wed the prince instead. King Hans refused. Even though his personal affinity for France had enamoured him to the match, he had come to the realisation that his hope of dragging Louis into his conflict with the Hanseatic traders and their Swedish pawns would come to naught. The marriage would further France’s prestige and put a French princess on the throne of a vast state on the Holy Roman Empire’s northern border, but it would do little to aid Hans in his quest to bring the Hanse to heel and end trade with his rebellious Swedish subjects.

Frustrated, King Hans made one last feeble attempt at securing a bride for his son before his passing, but his overtures towards a Polish princess came to naught and stranded on Danish inaction. Likely, the cause of the failure is to be found in the fact that, just like the marriage negotiations with the grand duke, the Polish proposal was meant to drive a wedge between the Polish realm and the Swedish rebels who had sought its support. Once the Poles lost interest in aiding the Swedes, king Hans lost interest in the Polish princess and thus Christian remained a bachelor at the time of his father’s death.

However, the military developments on the continent would dictate that Christian II would not remain so for long.

In the late summer and early autumn of 1513 The War of the League of Cambrai had taken a catastrophic turn for the French and their Scottish allies. Henry VIII of England had crossed the Channel, linked arms with the emperor and decisively defeated a French army at Guinegate before capturing the town of Tournai. A month later, the industrious king James IV of Scotland was killed in action alongside the flower of Scotland’s chivalry at the Battle of Flodden. Consequently, the Holy League seemed poised to once and for all end any French pretensions to Italian hegemony.

Desperate for new allies, Louis XII remembered the young Madeleine de la Tour and the stranded marriage plans with the Northern king. Now more than ever the need for a friendly power on the Empire’s flank seemed imperative. As a result, on the 5th of October 1513, Louis issued Antoine d’Arcy, the lord de la Bastie[5], with a royal instruction to seek a marital and military alliance with the new king of Denmark and Norway. Furthermore, the French king pledged a dowry of a 100.000 francs. Setting off with great haste, d’Arcy reached Edinburgh a month later to join forces with a Scottish embassy headed by Andrew Brownhill and together they made the perilous crossing of the North Sea. The combined Franco-Scottish diplomatic mission reached Copenhagen in early march 1514[6] and was received with all the splendour such an embassy demanded. However, as d’Arcy and his Scottish colleagues made their representations before Christian, they found the situation drastically changed. The king had taken personal charge of the matter of his marriage.

Wood-cutting illustrations from Der Weisskönig, ca. 1515 by Hans Burgmair. Left: English troops armed with longbows and flying the Tudor banner rendezvous with Imperial forces before the Battle of the Spurs. Right: King James IV of Scotland lies slain at Flodden whilst his army routs over his body and broken standard. The Franco-Scottish military situation in late 1513 was not decidedly enviable.

Shortly after the conclusion of the negotiations pertaining to his accession charter, Christian had sat in council with his friends and closest family to debate the best match for a prince such as himself. Although the king like his father was personally enamoured to France, he understood the political limitations of a union with that country[7]. A French alliance would pivot the Oldenburg state against the pope, the king of England and, most importantly, the Emperor himself. The geographical realities being what they were, it would furthermore be highly unlikely for France to be able (or willing) to support the king in his ambition to restore royal authority in Sweden. Given the empire’s proximity and the emperor’s authority, the logical outcome would be to seek a bride from the House of Habsburg.

In the late summer of 1513, when French military fortunes plummeted, Christian wrote his uncle Frederick III Elector of Saxony[8] to enquire if he thought he had a chance at obtaining the hand of one of Emperor Maximilian I’s granddaughters. Christian himself preferred the oldest, Eleanor, but his uncle advised against it. Instead, he proposed that the younger Isabella would be far more suitable, as it appeared Eleanor had already been betrothed to another. To such a match, Frederick wrote, Maximilian himself had given his consent. Isabella was then only 12 years of age, 20 years younger than her proposed husband.

On the 6th of November 1513, just as the French embassy of d’Arcy arrived in Scotland, a delegation left Copenhagen for the imperial court at Linz. Representing the king was Mogens Gøye who was to act as his sovereign’s proxy in the proceedings. At his side Gøye had the bishop of Schleswig, Godske Ahlefeldt, and the knight and councilor of the realm, Albert Jepsen. The bishop was an eminently learned man with a commanding grasp of the latin language and was thus well suited to accompany the worldly splendour of the two noblemen.

However, the Emperor, it turned out, was just as inclined to use the marriage as a way to further his own designs as his counterpart Louis XII. The Grand Master of the Teutonic Order had for some time been begging Maximilian for aid against Polish encroachment on his territory and the Emperor had come around to the idea of forming a grand alliance to help the Ordensstaat. In this alliance the participation of Christian II would be quintessential. The Emperor thus proposed that a condition of the marriage of state be that the Danes would have to spend a third of Isabella’s dowry on a war against the Poles in defence of the German knightly order of the Baltic. This, however, was anathema to established Danish foreign policy. There existed widely cordial relations between the two courts and vital commerce between the two states flowed across the Baltic Sea. Furthermore, hostilities would revitalize the possibility of Polish support for the Swedish separatists and remove the pressure the Poles could bring to bear on the important Hanseatic port of Danzig whose trade with Sweden would need to be cut off in the event of hostilities breaking out.

On the advise of Frederick III, the three Danish deputies made vague promises and offered a counter-proposal. The king of the northern realms would gladly join a defensive alliance of the Terra Mariana, provided that the Electors of Saxony and Brandenburg likewise gave their support[9]. To this the imperial negotiators could not object and as such the matter was settled amicably whilst the Danes avoided an outright provocation of the Polish government.

The Emperor Maximilian I and his family by Bernhard Strigel, 1516. The Emperor is shown with his first wife Mary of Burgundy and their son Philip the Fair who had predeceased his father in 1506. In front are Philip’s children Ferdinand and Charles as well as Louis of Hungary, who would be adopted by Maximilian.

Whilst awaiting further counsel from the Elector of Saxony, the three delegates received word of the arrival of the Franco-Scottish embassy in Copenhagen. D’Arcy was working hard at convincing the king of the merits of a marriage to the young Madeleine and dangled the promise of the large dowry in front of Christian and his royal council.

Although the king had already elected against a French alliance, he decided to put on a good face regarding the envoys of Louis XII. D’Arcy and Brownhill were politely delayed and protracted at court with vague and uncommitted negotiations were commenced, whilst Gøye and his companions were ordered to continue with their endeavours in Linz.

Even though the issue of the anti-Polish coalition had been settled satisfactorily to both parties, there still remained two issues keeping the parties from signing the pact. First of all was the issue of Isabella’s age. The Imperial negotiators did not think the princess mature enough to wed the northern king immediately after the conclusion of the pact and pushed for a prolonged engagement period before a consummation of the marriage. To the Danish representatives this was problematic. They knew their king was impatient for a wife to secure the dynasty, the production of an heir was, after all, a great matter of state. The second issue was the size and downpayment of Isabella’s dowry.

An agreement would soon be reached on the first issue with the Danes conceding to the demands of the imperial court. The wedding would be conducted in two stages. A marriage by proxy would be held at the same time in Copenhagen and Brussels, where the princess lived under the tutelage of her aunt Margaret of Austria with Mogens Gøye serving as a stand-in for the king of Denmark. The second wedding ceremony would be held in person the year after in june 1515, allowing for Isabella to remain with her family until she had almost turned 14.

The second issue however, proved a harder nut to crack. The imperial councilors refused to settle on a given amount and it was only by the intermission of the Emperor himself that a solution was found. Isabella would bring a quarter of a million Rhenish guilders into her marriage - a sum of staggering proportions[10]. However, the imperial negotiators proclaimed that even the mighty House of Habsburg and their Fugger bankers did not possess pockets that ran quite so deep. Instead of a single payment, they asked that the dowry be broken into three installments, to be paid on the day of the wedding in 1515, 1516 and 1517.

Gøye and his compatriots very well knew that such an arrangement would disappoint their master greatly and as a result the negotiations ground to a halt. As the two parties retreated to reevaluate their positions, the Danish embassy became alive with rumours. Grooms and squires lived in uncertainty on how long they would remain in Linz. Stewarts were being told one day to purchase supplies for a long journey only to receive counter-orders on the morrow. Into this state of confusion, bishop Ahlefeldt casually remarked at a dinner with local dignitaries that the king had other suitors - such as the eminently beautiful Madeleine. As the three delegates let the news of the French “negotiations” slip, it soon found their way to the imperial councilors where a cold feeling of panic immediately took hold.

Isabella of Austria by the Master of the Legend of the Magdalen, ca. 1515.

Although the French and Scots were surely wrong-footed, the League had failed to keep up its momentum and end the war on their own terms. Furthermore, there were even rumours of Henry VIII seeking a separate peace with Louis, frustrated as he was by the lack of profit, which his investments in the Emperor’s war had garnered[11]. A new front in the north would prove disastrous for the imperial war effort and even though a great deal of the imperial councilors saw the ploy of Ahlefeldt for what it was, the danger was simply too great to ignore. Consequently, when the two parties reconvened for further talks, the imperial position was much more pliable.

The amount of the dowry would remain at 250.000 guilders, but the dates for the installments would be moved ahead. A quarter of the sum would be paid at the proxy marriage in Brussels that very same year whilst the yearly installments would follow as originally proposed until 1516. The dowry would prove to be of enormous importance to the king and his desire to see the Oldenburg three-state union revived. If paid in total, the dowry would enable him to hire more than 5000 German Landsknechts and pay their wages for an entire year, giving credence to the latin phrase pecunia nervus belli (money is the soul of warfare)[12].

Emperor Maximilian was also pleased with the successful end of the negotiations. He had turned a potential (or imagined) French ally around and bound him by marriage to his house, a policy deeply rooted in the Habsburg polity. Furthermore, as he wrote his daughter Margaret (who did not share his enthusiasm for the match) “... the marriage shall bring great joy to the House of Austria-Burgundy and especially our Netherlandish possessions who will benefit greatly in the ways of trade and commerce [...] my good son’s daughter couldn’t have achieved a better match, unless it was permitted a prince to take two wives.”[13]

On the 7th of June, the Danish company reached Brussels, where the Count of Hoorn received them in the name of Isabella’s brother Charles and her aunt Margaret of Austria, the Habsburg viceregent in the Netherlands. Great honour and splendour were showered on Christian II’s representatives, as the mood in the city was decidedly pro-Danish at the time. Despite the extra loans and taxes levied on the rich Dutch merchant cities by the imperial government to fund the dowry of Isabella, the king had enamoured himself to the people of Brussels by dispatching one of his trusted naval commanders, Søren Norby, alongside a small fleet and 500 men to aid the Emperor in his feud against Charles II Duke of Guelders[14].

Four days later Isabella wed Christian II through his representative Mogens Gøye in a pompous ceremony presided over by Jacques de Croÿ, bishop of Cambrai, and in the presence of her siblings as well as the Duke of Saxony[15] and the elector of Brandenburg. After another four days of celebrations, the embassy received the first quarter of the dowry and began their long journey home.

They had been gone for half a year.

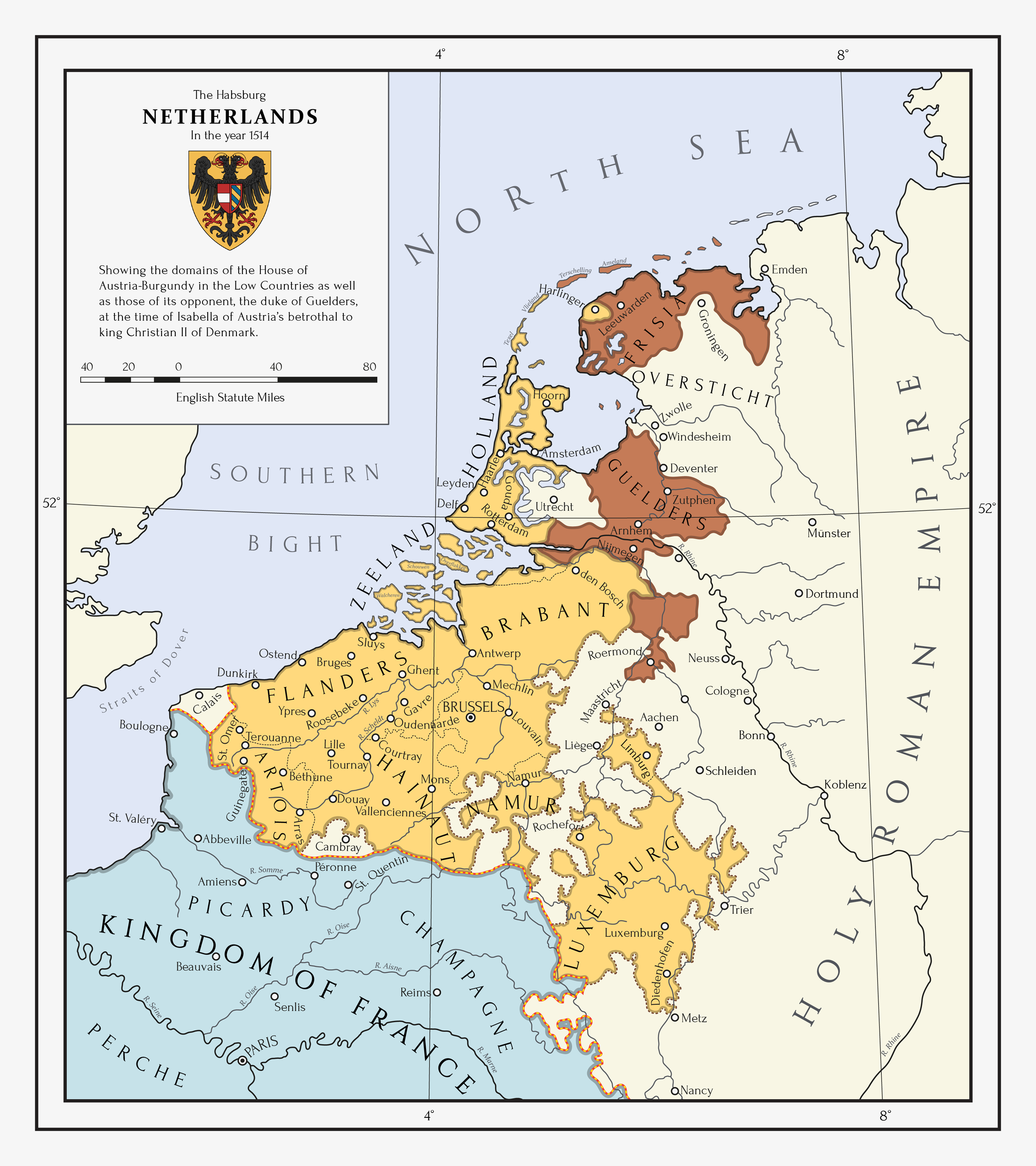

The Habsburg possessions in the Netherlands at the time of Isabella and Christian's betrothal in 1514. The house of Austria-Burgundy had spun a web of matrimonal alliances throughout the continent which has pivoted it to the forefront of European grand politics. The Habsburg Dutch domains constituted some of the richest and most urbanised areas in all of Europe at the turn of the 15th century.

Footnotes:

[1]Being the perception of Margaret of Austria, to be precise. Outside of Scandinavia, at this point of time, full beards were considered inappropriate and somewhat barbaric.

[2]Who would go on to father Ivan the Terrible.

[3]Anne of Brittany, wife of Louis XII

[4]Who IOTL became the mother of Catherine de Medici.

[5]A good friend of the previously mentioned Duke of Albany.

[6]The proposal and embassy was also made in OTL, however, various delays meant that the Scots and French only reached Copenhagen on the 30th of April - the very day after the marriage contract between Christian and Isabella had been signed! ITTL, they haul their behinds along a bit faster.

[7]Just like he did in OTL.

[8]You know, the guy who went on to protect Luther in OTL after the Edict of Worms.

[9]This was actually an OTL proposition by Maximilian. The Danish response is the same as in OTL, too.

[10]The same amount as in OTL. To illustrate how truly staggering an amount the dowry constituted, it would equal roughly 14 million Euro in today’s money according to this site: http://www.iisg.nl/hpw/calculate2.php

[11]As he would go on to do in the summer of 1514.

[12]A rough estimate on my part. In 1522 the monthly wage of an infantry landsknecht was 4 guilders. A mounted soldier was paid 10 guilders a month. 4 guilders a month for 12 months equals 48 guilders for one year’s salary for a single infantryman Divided by 250.000 that should equal the pay for approximately 5200 soldiers.

[13]My own translation.

[14]In OTL, the flagship of Norby’s fleet “The Angel” was used by Charles V on his journey to Spain in 1517 to assume his Iberian crowns.

[15] John the Steadfast, the younger brother of Frederick III of Saxony.

Last edited:

Fantastic! There really isn't a better possible match than Isabella when you look at the field. She is granddaughter to the Emperor, sister to the future King of Spain and likely Holy Roman Emperor while her brother-in-law will presumably become King of Bohemia-Hungary. Prestige-wise she outweighs Madelaine de la Tour d'Auvergne by a significant degree. She also brings an alliance to the Emperor and the Netherlands alongside a massive dowry. I know you mention it corresponds to 14 million Euro in modern currencies, but that is honestly underselling it significantly. What you aren't counting in with that statement is the fact that the money supply is much, much smaller which makes the sum of the dowry a good deal higher. I mean, you would have a hard time financing an army of 5000 professioal mercenaries for a year with 14 million euro, this is the equivelent of a country's GDP, and not even a small country at that.

The only possible way Madelaine might have outweighed Isabella as candidate was her age, and resultant ability to marry immediately, and that she stands as co-heir with her sister to quite significant domains in France. However, given that she died in childbirth giving birth to her first child IOTL and particularly Francois I's (of OTL) tendency to lie, cheat and steal from even his close friends and allies to finance his war effort, Madelaine really comes out as a poor candidate.

Here is to hoping that Christian and Isabella's marriage is happy and fruitful. You really couldn't ask for a better match.

The only possible way Madelaine might have outweighed Isabella as candidate was her age, and resultant ability to marry immediately, and that she stands as co-heir with her sister to quite significant domains in France. However, given that she died in childbirth giving birth to her first child IOTL and particularly Francois I's (of OTL) tendency to lie, cheat and steal from even his close friends and allies to finance his war effort, Madelaine really comes out as a poor candidate.

Here is to hoping that Christian and Isabella's marriage is happy and fruitful. You really couldn't ask for a better match.

So a lot of very welcome context, I have great difficulty finding detailed sources of the period since I only speak English, and a single divergence. Christian being a bit more financially secure early in his reign. Although the nonexistence of Dyveke as royal mistress will make Isabella's early years easier, and also improve relations between Christian and his in-laws.

Wonder what exactly Christian will use the money for. An earlier invasion of Sweden, or simply a bigger one at the OTL time? While more luck when going to war with Sweden will help, it will merely be a patch, Wonder if Christian has any ideas to actually solve the underlying problems with Sweden, hopefully different ones than the OTL Stockholm Bloodbath.

Wonder what exactly Christian will use the money for. An earlier invasion of Sweden, or simply a bigger one at the OTL time? While more luck when going to war with Sweden will help, it will merely be a patch, Wonder if Christian has any ideas to actually solve the underlying problems with Sweden, hopefully different ones than the OTL Stockholm Bloodbath.

Last edited:

Next update might be a bit belated as my RL has been getting quite busy as of late. As a way of making amends, I've added a map of the Habsburg Netherlands that I didn't manage to finish in time for posting the last chapter.

He really hit the nail on the head with that match indeed. As far as I know, no other Scandinavian monarch ever married into such a prestigious house as the Habsburgs.

I'm somewhat uncertain on how likely it will be for Christian to obtain the remainder of the dowry, given the trouble he had in OTL. Hopefully someone learned in the reign of Charles V will come to my rescue (or I sit down and read some damn books!).

It will improve the Habsburg-Oldenburg relations tremendously! IOTL, Margaret even wanted to abort the wedding when she heard of the king's mistress' prominent role. Furthermore, the Habsburgs really disapproved of having one of the future emperor's sisters being 'shamed' so. Some even speculate that the imperial ambassador had a hand in Dyveke's murder!

The extra money will have an incredible important impact on Christian's reign, which should become gradually clearer as we move on towards the reckoning with the Swedish care taker government.

Fantastic! There really isn't a better possible match than Isabella when you look at the field. She is granddaughter to the Emperor, sister to the future King of Spain and likely Holy Roman Emperor while her brother-in-law will presumably become King of Bohemia-Hungary. Prestige-wise she outweighs Madelaine de la Tour d'Auvergne by a significant degree. She also brings an alliance to the Emperor and the Netherlands alongside a massive dowry. I know you mention it corresponds to 14 million Euro in modern currencies, but that is honestly underselling it significantly. What you aren't counting in with that statement is the fact that the money supply is much, much smaller which makes the sum of the dowry a good deal higher. I mean, you would have a hard time financing an army of 5000 professioal mercenaries for a year with 14 million euro, this is the equivelent of a country's GDP, and not even a small country at that.

The only possible way Madelaine might have outweighed Isabella as candidate was her age, and resultant ability to marry immediately, and that she stands as co-heir with her sister to quite significant domains in France. However, given that she died in childbirth giving birth to her first child IOTL and particularly Francois I's (of OTL) tendency to lie, cheat and steal from even his close friends and allies to finance his war effort, Madelaine really comes out as a poor candidate.

Here is to hoping that Christian and Isabella's marriage is happy and fruitful. You really couldn't ask for a better match.

He really hit the nail on the head with that match indeed. As far as I know, no other Scandinavian monarch ever married into such a prestigious house as the Habsburgs.

I'm somewhat uncertain on how likely it will be for Christian to obtain the remainder of the dowry, given the trouble he had in OTL. Hopefully someone learned in the reign of Charles V will come to my rescue (or I sit down and read some damn books!).

So a lot of very welcome context, I have great difficulty finding detailed sources of the period since I only speak English, and a single divergence. Christian being a bit more financially secure early in his reign. Although the nonexistence of Dyveke as royal mistress will make Isabella's early years easier, and also improve relations between Christian and his in-laws.

Wonder what exactly Christian will use the money for. An earlier invasion of Sweden, or simply a bigger one at the OTL time? While more luck when going to war with Sweden will help, it will merely be a patch, Wonder if Christian has any ideas to actually solve the underlying problems with Sweden, hopefully different ones than the OTL Stockholm Bloodbath.

It will improve the Habsburg-Oldenburg relations tremendously! IOTL, Margaret even wanted to abort the wedding when she heard of the king's mistress' prominent role. Furthermore, the Habsburgs really disapproved of having one of the future emperor's sisters being 'shamed' so. Some even speculate that the imperial ambassador had a hand in Dyveke's murder!

The extra money will have an incredible important impact on Christian's reign, which should become gradually clearer as we move on towards the reckoning with the Swedish care taker government.

Next update might be a bit belated as my RL has been getting quite busy as of late. As a way of making amends, I've added a map of the Habsburg Netherlands that I didn't manage to finish in time for posting the last chapter.

He really hit the nail on the head with that match indeed. As far as I know, no other Scandinavian monarch ever married into such a prestigious house as the Habsburgs.

I'm somewhat uncertain on how likely it will be for Christian to obtain the remainder of the dowry, given the trouble he had in OTL. Hopefully someone learned in the reign of Charles V will come to my rescue (or I sit down and read some damn books!).

It will improve the Habsburg-Oldenburg relations tremendously! IOTL, Margaret even wanted to abort the wedding when she heard of the king's mistress' prominent role. Furthermore, the Habsburgs really disapproved of having one of the future emperor's sisters being 'shamed' so. Some even speculate that the imperial ambassador had a hand in Dyveke's murder!

The extra money will have an incredible important impact on Christian's reign, which should become gradually clearer as we move on towards the reckoning with the Swedish care taker government.

Christian II's marriage to Isabella of Burgundy is the highest match ever achieved by a Danish monarch, there were martial matches to various royal families but to my knowledge never a match at that level before or since.

Regarding the dowry, it really depends on how cash-strapped Charles V is and how much he needs it. IOTL he very rarely got the slightest break - resulting in a constant drain, only mitigated by the oceans of silver and gold crossing the Atlantic from the Americas. I think one possibility, given the better relationship and that Charles might be more hesitant to ruin good relations with Christian, might be other possible measures of recompense - promising diplomatic support against the Hanse or perhaps pawning a province or source of revenue to his brother-in-law. If you want to get creative with it, though I doubt the plausibility, there are plenty of grants and rights in the Americas to distribute - just consider the Welser's control of Klein-Venedig.

A better, earlier relationship with Isabella is going to be incredibly important. It secures stronger Imperial support, might counter some of the Hanseatic pressure, improves relations with the Dutch and puts Christian in a stronger position.

Threadmarks

View all 37 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 26: White Rose Victorious Chapter 27: The One Good Harvest Map of Denmark and Schleswig at the End of the Late Medieval Period (ca. 1490-1513) Chapter 28: On the Shores of a Restless Sea Chapter 29: A Thorny Olive Branch Chapter 30: Via Media Chapter 31: The Garefowl Feud Chapter 32: The Queen of the Eastern Sea

Share: