Happy for you.Thank you all - I just started a new job and moved to Brooklyn, so that dropped a car battery on my spare time. But I'm back now!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

TLIAW: Against the Grain

- Thread starter Vidal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 11 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

36. Cord Meyer (R-NY), 1961-1969 37. Thomas D'Alesandro, Jr (D-MD), 1969-1974 38. Dolph Briscoe Jr. (D-TX), 1974-1981 39. Gordon Liddy (C-NY), 1981-1989 40. Tom Kahn (D-MD), 1989-1993 41. Luci Baines Johnson-Kennedy (D-TX), 1993-1997 42. J. Michael Crichton (NR-IL), 1997-2000 43. James G. Watt (NR-WY, then F-WY), 2000-2001Rust Belt cities when they finally get a break after decades of deindustrialization:

I’ll fix it. Which part?Part of the writeup is black on black and only shows up when I highlight it.

EDIT: Should be fixed.

Last edited:

Indiana Beach Crow

Monthly Donor

John Stross is to OTL Michael Crichton, as Billy and the Cloneasaurus is to Jurassic Park.Under the pseudonym John Stross, he wrote five novels in four years, many of which critiqued New Deal Democrats and their legacy.

Last edited:

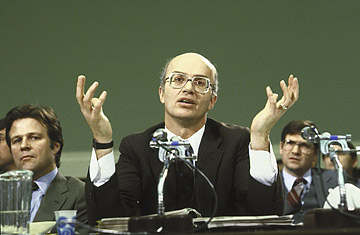

43. James G. Watt (NR-WY, then F-WY), 2000-2001

James G. Watt (NR-WY, then F-WY)

February 19, 2000 - January 20, 2001

“If the troubles from environmentalists cannot be solved in the jury box or at the ballot box, perhaps the cartridge box should be used.”

February 19, 2000 - January 20, 2001

“If the troubles from environmentalists cannot be solved in the jury box or at the ballot box, perhaps the cartridge box should be used.”

Some years after his presidency, during the trial of James Watt, Common Sense’s Bill Moyers went on a furious diatribe in which he called Watt, among other things, “a political arsonist who’d burn this entire country down for a quick buck.” This resonated with many Americans, though this was hardly a surprise for perhaps the most hated president in modern memory - apart from a small core of dedicated supporters, over 80% of respondents listed Watt as the worst president in American history when surveyed. Despite a tenure of only 11 months, James Gaius Watt’s decisions reverberate throughout modern American history.

Watt began his political career as an aide to William Henry Harrison III, a senator from his native Wyoming and perhaps one of the most conservative Republicans in Congress. With Harrison’s encouragement, Watt took a job with the Department of the Interior, retaining that post until Meyer turned to D’Alesandro. Out of a job with a new Democratic administration, Watt returned to his native Wyoming, convinced by Republican leaders there to pursue the open house seat there in 1970. Winning the election handily, he became one of the staunchest conservative Republicans in Congress, touting his record as opposing every single new government program in campaign mailers. From there, he came to notoriety in the new Conservative Party, supporting the merger wholeheartedly. Though Liddy passed over him for Secretary of the Interior, he still remained one of Liddy’s most ardent supporters in Congress, a frequent liaison between leadership and the White House.

Then the Conservative Party became the New Republican Party, and Watt, among several other Liddyites, opposed removing “the best president we’ve had since Lincoln” from their party. Feeling that the New Republican caucus was not a place where he could rise, Watt decided to jump into the race for Governor of Wyoming. Defeating Democrat Buddy Hunt in one of the nastiest races of the year, even publicly outing Hunt as a gay man, Watt ultimately won by less than a percent. Doctrinal conservatism played surprisingly well in an agrarian swing state, with many younger farmers having simply forgotten the horrors of the depression and furious about limits on the sale of their surplus products and large producers wanting to tear down preserved land on his watch. Though he briefly earned national ridicule for his statement that “I do not know how many future generations we can count on before the Lord returns” in relation to his anti-conservationist policies, Watt gained a reputation as the model of conservative governance, a favorite of business interests for his no-holds-barred deregulatory approach and right-wing preachers for his social conservatism and open references to his Dispensationalist Christian faith.

This made him perfect for Michael Crichton. New Republican leaders were convinced his “urbane conservatism” was appealing to anxious suburbanites and younger conservatives, but not the older faithful and the business world. Watt would bring conviction to Liddyite economics and a certain religious gravitas that Crichton did not desire to have. Plus, making Crichton look more moderate by comparison hardly hurt in a general election. Reluctantly agreeing to bring Watt aboard, Crichton largely left him to focus on the south and mountain west, an area of relatively low concern to the campaign. This would continue throughout the administration, with Watt largely marginalized and left to handle issues of low import to Crichton.

But Watt still found his way to prominence. Making himself something of an unwanted hatchet-man, Watt found himself in public spats with left-wing journalists, environmentalist groups, virtually every Democrat who breathed, and even popular musicians who staged a “protest concert” in Washington. Though this made him markedly more unpopular than Crichton as a lightning rod for controversy, he seemed to revel in the attention. When he was caught on a hot mic making a racially-charged joke mocking the federal government’s affirmative hiring practices, Watt refused to apologize, instead blasting the “high-and-mighty culture of correctness around here” for telling him off over the joke. No matter how many reasons there were to hate him, nobody could pretend that Watt wasn’t a fighter, and to the sect of the populace who agreed with him, he was the ideal of a leader.

Antagonizing the national press is never a good idea, but especially not when you’re as close to lobbyists as James Watt. Investigative reporters began publicizing his meetings with prominent lobbyists. Everything from unofficial meetings from mining companies to even a large cruise with oil lobbyists became front-page news. But there was more to the story than simple lobbying work. Watt had claimed that his finances were no longer handled by him as soon as he took office, but the investigations into his lobbying ties found that he had received significant financial “gifts” throughout his career, including a new home in Wyoming worth over $1 million. Then those gifts had become more recent, including one alleged monetary gift delivered to him during his tenure as Vice President. Under public pressure and frankly not a fan of Watt to begin with, President Crichton directed the Department of Justice to appoint an independent investigation into Watt’s activities in 1999.

Then came February 19th, and regardless of whether Watt was under investigation or not, he was in charge. Immediately, Watt moved to protect himself in the ways that Crichton refused to. He dismissed the probe against him, firing those involved. Overnight documents pertaining to Watt’s activities and alleged bribery disappeared. To this, Crichton’s staff began resigning. The executive offices emptied out at first, but the cabinet soon followed suit. All in all, six different Secretaries resigned their posts in the February Massacre, citing irreconcilable differences with Watt in some cases and a sincere belief that he was abusing his power in others. Watt simply acted as if he never needed them anyways, making quick appointments more in line with his own ideals. Persistent calls for his resignation as vice president simply dropped the word vice, and life moved on as Watt claimed he would never surrender.

The New Republican Party found itself in an extremely distasteful situation over James Watt. On one hand, denying an incumbent president the party’s nomination was sure to throw their chances into jeopardy, and Watt did have his supporters. On the other, the party knew that Watt was a scandal-tarred extremist who would surely burn their chances at holding power. Ultimately, under the direction of party chair Ben Stein, they voted to endorse a challenge to Watt and voiced their opposition to his renomination. Losses across the coasts and in the delegate-rich Midwest - even memorably losing to “no preference” in Minnesota - ensured that Watt simply couldn’t attain the nomination anymore, and the nation breathed a sigh of relief. But Watt was hardly down and out. The New Republican Party was hardly a good fit for him anyways, nor was any party that would decry him as some right-wing radical. During an address in Washington D.C., Watt announced to the nation that he was leaving the New Republican Party, officially registering as a member of the Frontier Party, and would stand as their presidential candidate that November.

Now unbound by the New Republicans, Watt grew more strident in his opinions. Having made murkily pro-Sagebrush comments as vice president, as the highest-profile Frontier Party member those comments grew less ambiguous. Where other party members disavowed violence, though, Watt relished in it. No president since maybe James Buchanan had truly condoned violence against the very government he led, but Watt still implied in rally after rally that the cartridge box was the best method of disposing of environmentalists. Quickly the other major parties issued condemnations of Watt, but he simply used those condemnations as proof of the size of the enemy they were up against. Though the rebellion had seemingly already fallen from its peak, hearing presidential legitimization of their actions reinvigorated the movement. Within weeks, attacks on government offices in the mountain west spiraled out of control as the federal government seemingly refused to put the rebellion down by force. State governments picked up the slack where they could, but they didn’t have nearly as much ability to put down the rebels, and in cases in the ensuing years such as Governor Harry Reid state officials were targeted for retaliation.

Watt’s conduct horrified members of Congress of all stripes, except perhaps the newly-enlarged Frontier Party. Though Speaker Sensenbrenner appreciated much of his agenda, under pressure of removal from his post due to “Ecology Republican” defections he agreed to draft articles of impeachment against James Watt. The articles, drafted over his abuse of power and conduct unbecoming of the presidency, quickly sailed through the House as Democrats, Utopians, and Proletarians voted unanimously to remove Watt and New Republicans were told to vote their conscience. However, the Senate would prove trickier. While the trial stretched through the summer, casting a pall over the election process, Watt’s legal team provided snappy soundbites to spread digitally and for supportive radio hosts out west to pick up. The proceedings convinced nobody, though. Small plains states had always had an outsize impact in the Senate, and Frontierist defectors in the west - including Idaho’s unique Utopian-to-Frontier defector T. J. Kaczynski - and southern conservatives alike found that Watt was within his rights to say what he wanted and that he had no real responsibility for how people took his words. In the end, by just two votes, Watt’s impeachment had failed, a feat Watt touted by holding up a newspaper headline in a televised address from the Oval Office.

Fortunately for those who found Watt objectionable and even outright dangerous - otherwise known as the vast majority of the political spectrum - the election was hardly three months away, and given his record-low approval rating of 9% Watt was sure to lose the election. Nobody knew how the Frontier Party’s presence would impact the race given its prevalence solely in low-population western states, and fears of a hung election due to an outsize influence by Watt on the electoral college despite a likely single-digit result seemed all too likely. In the end, though, the fears of a hung election proved to be valid, and that night three candidates declared a legitimate victory - one from a popular plurality, one from an electoral plurality, and one from the White House.

While terror spread throughout the nation at the prospect of no decision, the situation was quite different out west. The few states that ultimately supported Watt were furious that their champion had been denied an outright victory, and Watt’s speech declaring that “patriotic Americans will continue to fight for their constitutional rights with or without me” invigorated them. Overnight, demonstrations by spurned Sagebrushers filled state capitals across the Rockies, declaring that any federal government was illegitimate and could not touch them or their property without their consent. Watt’s team, led by Tom Charles Huston, began to covertly organize with Sagebrush groups, planning a show of force that Huston testified was “wholly intended to secure Watt’s position and pressure this body into conceding to him.” As the new Congress convened to vote for a new president, a horde of truckers, farmers, and ranchers descended on Washington, armed and chanting for the removal of the government’s leadership and the reinstatement of Watt. Skirmishes with Capitol police soon turned violent, and before long shots had been fired and the Battle of the National Mall had begun. As Watt claimed he would calm the crowd with four more years and the Virginia and Maryland National Guards supplemented the police presence, Congress defied Watt. A “crisis administration” pact caused a nearly-unanimous vote where a new president would be sworn in. As the riots swelled and mirrors began from Salem to Topeka, Watt simply left Washington for Wyoming, with his last order issuing a self-pardon for all alleged crimes that the Supreme Court would strike down within the year.

Last edited:

Watt’s team, led by Tom Charles Huston

The real joy of this radioactive shitshow entry is that such Faberge-level easter eggs get dropped in it casually. Watt and Huston are definitely two fellas who were going to find their way to the top of the freakshow crab pot in a post-Liddy world.

"Wow, this guy sounds like a real piece of work. I wonder what he got up to in real life. Probably some crank columnist, or something…

… Oh… he was Secretary of the Interior…"

The events of this TL, and All Along the Watchtower before it, can be pretty horrifying, but I think the most horrifying thing of all is learning that a lot of these figures are not quite as marginal as I had assumed…

… Oh… he was Secretary of the Interior…"

The events of this TL, and All Along the Watchtower before it, can be pretty horrifying, but I think the most horrifying thing of all is learning that a lot of these figures are not quite as marginal as I had assumed…

Last edited:

AllThePresidentsMen

Banned

That’s high praise — he’s barely a president, more Agatha Trunchbull fused together with Spiro Agnew.Horrific President

more Agatha Trunchbull fused together with Spiro Agnew.

This, with a little Electric Fundie Jesus thrown in.

What a time to be aliveIdaho’s unique Utopian-to-Frontier defector T. J. Kaczynski

including Idaho’s unique Utopian-to-Frontier defector T. J. Kaczynski

Michael Crichton gives me heavy Donald Trump vibes but yet seems to genuinely want to improve America. Crichton's "America First" parallels "MAGA". Really impressed, well done. @Wolfram

Last edited:

.......You tagged the wrong person, it's just Wolfram without the 101Michael Crichton gives me heavy Donald Trump vibes but yet seems to genuinely want to improve America. Crichton's "America First" parallels "MAGA". Really impressed, well done. @Worffan101

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 11 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

36. Cord Meyer (R-NY), 1961-1969 37. Thomas D'Alesandro, Jr (D-MD), 1969-1974 38. Dolph Briscoe Jr. (D-TX), 1974-1981 39. Gordon Liddy (C-NY), 1981-1989 40. Tom Kahn (D-MD), 1989-1993 41. Luci Baines Johnson-Kennedy (D-TX), 1993-1997 42. J. Michael Crichton (NR-IL), 1997-2000 43. James G. Watt (NR-WY, then F-WY), 2000-2001

Share: