2000

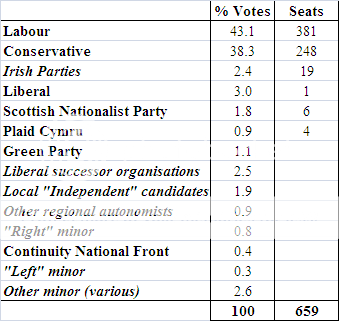

Despite broadly successful efforts by Patten to modernise his party and bring it into the 21st Century, it would be Prime Minister Davies who would lead the Labour party to an unprecedented third term. Though the popular vote totals were very close indeed, strong dis-proportionality in the electoral system (with generally lower turnout in Labour-held seats) resulted in the government being reelected with a comfortable majority.

Lab 361 (44%),

Con 269 (44%),

Lib 1 (1%)

Labour majority 63

In the months leading up to the election there had been growing internal Conservative Party anger towards Patten. Their leader was accused of selling out, of conceding too much, and of not looking out for “real” conservative values. It was a true case study in introspection. Had the party performed much worse in the 2000 election, that anger might have erupted in a repeat performance of '92. As it was, that anger became diverted instead towards the inherent unfairness of the electoral system. Accusations of gerrymandering and of electoral fraud flowed from the right-leaning press. The “over-representation” of Scotland and Wales was blamed, as was a perceived reluctance of the Electoral Commission to redraw boundaries to account for declining inner city populations. The Conservatives had won within a hundred thousand votes of Labour. Indeed they had won more votes than at any other time in the party's history. As contentious elections went, there were few at the time to rival that of 2000. Once Labour's clear victory became apparent, Patten stated clearly and publicly his strong intention to remain as party leader. Whether his determination and preemptiveness wrong-footed his opponents or otherwise, Conservative MPs would effectively assent. The old image of ruthlessness was slowly disappearing.

Content with being the most electorally successful leader in Labour Party history, and approaching his 65th birthday, Davies chose to retire in 2001. In a heavily contested leadership election it was Foreign Secretary Glenda Jackson (two years Davies' senior) who ultimately prevailed.

Glenda Jackson

Jackson had first been elected to parliament in 1992. After a short period on the backbenches she would become a junior Minister at the Department of Trade and Industry in 1994. Following the '96 election Jackson entered cabinet as Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, before moving to Education, and subsequently being promoted to Foreign Secretary in the 2000 post-election reshuffle. Having started her political career later in life, and surrounded by many young and ambitious junior ministers, Jackson was initially underestimated. Over two terms in government she would prove to be among the most competent and diligence of frontbenchers, adeptly managing the 1998 haulage workers strike and averting a potentially long-running dispute. In the Commons she would channel her long stage career, delivering the style of impassioned oratory increasingly absent in a chamber filled with of technocrats and PPE graduates. As ministerial resignations grew with the tenure of the the Prime Minister, there was always “room at the top”. To those who knew her, it was no surprise that Jackson climbed all the way.

In the eighteen months from her appointment as Foreign Secretary to the October 2001 leadership election, Jackson would establish herself as the figurehead of Britain's new “Ethical Foreign Policy”. This policy-shift marked a clear change from the “pragmatic isolation” of the early Davies years and was initially resisted by Foreign Office mandarin. Yet it was one which chimed with public feeling, after a decade of depressing news stories on atrocities in Bosnia, Rwanda and Kosovo. Britain would be a force for good in the world, and the old Cold War mantra of “

my enemy's enemy...” was to be a thing of the past. Had the Prime Minister known the full scope of this new doctrine, he might have blocked it. Instead, weary of office and planning a retirement, the ropes were slack and there for the taking.

Jackson's public profile rose to its highest in these eighteen months. When a state-sanctioned terrorist attacks in Marseilles and a major bomb scare at the Berlin Olympics necessitated a NATO response, Jackson was thrown upon the world stage. Britain's interventions in Syria and Lebanon were limited and proportionate – the risk of escalation minimised through a policy of diplomacy-first. The cooperation of traditional allies could never fully be relied upon. The leaders of the rapidly integrating European Union, more comfortable with

realpolitik and preoccupied with planning complete economic union, remained somewhat bemused at the optimism and idealism of it all. In Washington there was indignance at this upstart who asked awkward questions about friendly regimes, who threatened the balance of power and the post-USSR “understanding” with the Russian Union, and who generally upstaged both her own Prime Minister and the newly inaugurated President..

When the 2001 Labour leadership election came there was always going to be one clear winner. While multiple rounds of voting were required to seal it, Jackson was always the front runner. For many party members and MPs, the symbolism of the first female Labour leader and Prime Minister was too much to pass up.

Jackson's leadership was notable for a number of reasons. Firstly there was the new “Third Way” approach to foreign relations, an officially sanctioned continuation of the Jacksonian Foreign Office. British relations with Europe became warmer than they had under Davies and previous governments. New links were forged with the Russian Union, and with a rapidly developing China. Towards the US, Jackson remained critical, resisting calls for further Middle Eastern interventions and generally being a thorn in the side of the Alexander administration.

At home Jackson kick-started much of the UK's emerging “Green Industry”. In perhaps the government's most controversial move, this signalled an irreversible shift away from the old dependence on coal-fired power stations. It was a change that would hurt Labour most in its heartlands. An ambitious (and ultimately missed) target was set, for the generation of 15% of UK energy from renewable sources by 2015. Larger success came from policies designed to shift UK waste management from landfill to recycling. On the International stage once more, Jackson would play host to the 2003 Telford Environmental Summit. The quiet Shropshire town was transformed for a fortnight into a centre of statecraft and media attention. The location had been chosen by Jackson for a strong symbolic reason. Britain, as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, had a moral duty to take the lead on addressing the global issue of climate change. In was a call sincerely made and passionately argued, though one the world was ultimately not ready to hear. The summit accords were limited in scope and their support was far from unanimous.

Jackson also continued the Davies-era funding increases for public services. Wider university access, free at the point of use, and a unified National Care Service were among the products of this extra spending. Marking a departure from the Davies-led government, however, Jackson's Chancellors were less hesitant to make tax increases in certain areas, predominantly on income and capital gains. While income tax rises were carried out in a broadly “progressive” manner, many opponents were to criticise them for the later “brain drain” of Britain’s newly enlarged graduate population. “Hypothecation”, the earmarking of tax revenues for specific purposes, was also implemented for some heath and education spending. This latter technique had previously been favoured by the former Chancellor John Smith, who now fulfilled the role of behind the scenes advisor and confident to the Prime Minister.

Overall, the Jackson Premiership was characterised as a departure from the caution of the Davies years. While opposition rhetoric of a lurch to the “extreme left” was probably overstating it – the Jackson-led Labour Party's policies being well within the spectrum of fellow European social democratic parties – from 2001 onwards there was a clear move away from the late nineties consensus.

On the opposition benches Patten's Conservatives were making leaps and bounds in their public image. To the surprise of commentators and many of the party's own members, Patten had come out as fully supportive of the Government's environmental policies. On occasion he would seek to outflank Labour on social policies – channelling a message more liberal than conservative. A flagship policy going into the 2004 general election would be immigration reform – a policy not only popular with both business interests and liberal pressure groups, but also a counter to Labour's increasingly nativist stance. A further significant PR coup would come with the endorsement of former Home Secretary Lord Jenkins (at the time a crossbencher). For those traditional Tories on the right it was anathema. However barring the few fringe parties who increasing courted their support, those traditionalists generally had nowhere else to go. While Patten was increasingly in anticipation of a leadership challenge, none came. Conservative frontbenchers looked ahead to the election, optimistic that all they required was one last push.

AAH.com thread: DBWI: Glenda Jackson PM?

Ben_P: As it says on the tin. What if film star turned politician Glenda Jackson had become Prime Minister?

GoldenBrown: Glenda Jackson? The actress? Who's Deputy Prime Minister, Patrick Stewart?

Aethelred (banned): THEN I GUESS WE'D BE LIVING INA COUNTRY WERE WHITE MEN ARE 2ND CLASS CITIZENS, AND WHERE ANYTHINK NON-PC IS ILLEGUL!!

: Monkfish: Jackson's extreme left views would cause Labour to lose their biggest ever election defeat in 2004 – Patten would become Prime Minister and privatise everything including the NHS. In 2012 there would be a war with China over human rights.

SillyBilly: This is why I hate DBWI's...