Chapter 1: Introduction

Devvy

Donor

Chapter 1: Introduction

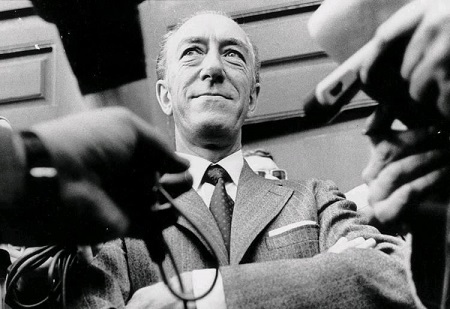

Hilmar Baunsgaard; the original architect of Nordek.

The Nordic Confederation traces it's history back to the post World War 2 era. Denmark and Norway were recovering from German occupation, whilst Finland recovered from two wars with the Soviet Union (and in view of the Baltics, for the very existence of the Finnish nation). Sweden, whilst neutral, very much felt the effects of the War, whilst Iceland, despite being a long way away from the mainland, was a glorified military base for the United Kingdom and United States. The Nordic Council came about as a consultative inter-parliamentary body, with members put forward by the national parliaments of Iceland, Norway, Denmark and Sweden; Finland later joining in 1955 after the death of Stalin and improving relations. Freedom of movement in the form of a joint labout market was instigated in 1952 with a passport free area, later reformed in to the "Nordic Passport Union" in 1958. Further action in "Nordic Social Security Convention" which allowed migrants greater access to unemployment benefits was implemented in 1955. 1967 saw Sweden embrace the switch from left-hand traffic (as in the UK) to right-hand traffic (similar to the rest of the Nordics, and Europe); many of the vehicles there were European imports anyway which corresponded with the new side of road driving.

Efforts towards a wider Nordic economic treaty floundered in the late 1950s however due to differing economic priorities and geopolitical priorities. As such, Denmark and Norway had followed the United Kingdom in applying for membership of the European Communities in 1963 due to the strength of trade between the two Nordic states and the UK. This 1963 application, as well as a subsequent attempt in 1967 were both declined with a French veto due to the perceived transatlantic relationship between the UK and USA. In light of this, the Danish Prime Minister (Hilmar Baunsgaard) in 1968 proposed a Nordic version of the EC; full Nordic economic co-operation. Both Sweden and Denmark especially were interested in a full customs union - that is the cessation of internal barriers and a common external tariff), whilst Norway needed capital to continue developing it's infrastructure - as well as providing an opportunity to create a common fisheries policy to "level up" it's coastal communities. Significant numbers of politicians in both Denmark and Norway favoured EC membership over what had become known as "Nordek" (NORD Economic Kommunity"), but the position of du Gaulle as French President proved an insurmountable obstacle; a position entrenched following his success in the 1969 French referendum and with no end likely in the short term it seemed.

As such, with seemingly few other options, Nordek was presented to the wider Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland) for signature; all 4 were existing EFTA members or associates, although the door was left open for Iceland to join later. The Swedish Government heavily backed the proposal (as shown in some of it's commitments). Opinion polls showed Finns had the greatest backing for Nordek at around 50% backing it, and 25% being ambivalent. Questions remained for Finland however, due to the presence of the Soviet Union next door, and Soviet politicians were suspicious. It was in light of this, with continued French vetoing of northern European nations joining the EEC (by then European Economic Community), that additional clauses in the Nordek treaty allowed for the suspension of Nordek if any member country proceeded to later accede to the EEC, whilst the treaty explicitly mentioned that the economic union would have no bearing on member's independent foreign and defence policies. It was explicitly to be a "purely commercial arrangement - not political" as some analysts put it, although some shared commerce rules would inevitably be required. It was an excellent reflection on the shared Nordic mindset that many of these rules could be co-ordinated initially by inter-governmental agreement and implemented by national law, rather than the supra-national political approach taken by the European Community.

President of Finland, Urho Kekkonen had a tightrope to talk in balancing Nordek and Soviet relations.

Either way, the "Treaty establishing a Nordic Economic Community" (later popularly referred to as the "New Kalmar Treaty" in a nod to the historical union between Nordic countries) was signed by the 4 countries in May 1970 (delayed for several months by Finnish-Soviet talks, with their Friendship Treaty extended by 20 years), and later ratified by the national Parliaments. It would establish a full customs union within 10 years between the 4 countries - with a few product/policy areas taking longer, including provisions for agriculture and fishing. Details of Nordek did not preclude any signatory from attempting to migrate to EEC membership, but any such move would likely trigger a swift "guillotine" effect on the Nordek economic links as documented in the treaty itself, in order to protect Finnish interests and allow the begruding acceptance of the Soviet Union next door. Later research during the 20th Century in to declassified material for the time indicated that Soviet acceptance was rooted in a desire to avoid a fully integrated European neighbour; by allowing Nordek to proceed, with safeguards to avoid Finland becoming too entangled, hopefully keeping west/north Europe economically divided at least partly.

Financial co-operation will see the enactment of three funds; general, agricultural and fisheries, for structural improvements and stabilisation in order to modernise markets and industry. Cooperation in industrial policy would be concentrated on areas in which the Nordic countries have important common needs, for example, pollution, health, oceanic research, space research, atomic energy and automation. Negotiations are taking place on the building of a Nordic atomic energy company - of interest especially to Sweden and Finland - on the successful Scandinavian Airlines model. This would see coordination in research, development and use of reactors, as well as the fuel market. The importance of adopting uniform company laws as soon as possible was emphasised, as is also need for uniform rules on government bankruptcy, the protection of patterns, unfair competition and the like.

All this would be administered by the Nordic Ministerial Council - with a member from each of the Nordic Governments, with all decisions to be unanimously, and a committee of officials under them to prepare the decisions and matters of the Council; and everything to start on the 1st January, 1971.

-------------------------------------

Hi all, so this is a redux/ rewrite of my "Nordic Twist to Europe" TL I did back in....2014 it seems. Wow. Except I changed the PoD to 1970, and the original Nordek treaty being signed, which is based on du Gaulle winning his French referendum, therefore not stepping down, and therefore there still being no immediate likelihood of UK/Ireland/Denmark/Norway joining the European Communities.

Hilmar Baunsgaard; the original architect of Nordek.

The Nordic Confederation traces it's history back to the post World War 2 era. Denmark and Norway were recovering from German occupation, whilst Finland recovered from two wars with the Soviet Union (and in view of the Baltics, for the very existence of the Finnish nation). Sweden, whilst neutral, very much felt the effects of the War, whilst Iceland, despite being a long way away from the mainland, was a glorified military base for the United Kingdom and United States. The Nordic Council came about as a consultative inter-parliamentary body, with members put forward by the national parliaments of Iceland, Norway, Denmark and Sweden; Finland later joining in 1955 after the death of Stalin and improving relations. Freedom of movement in the form of a joint labout market was instigated in 1952 with a passport free area, later reformed in to the "Nordic Passport Union" in 1958. Further action in "Nordic Social Security Convention" which allowed migrants greater access to unemployment benefits was implemented in 1955. 1967 saw Sweden embrace the switch from left-hand traffic (as in the UK) to right-hand traffic (similar to the rest of the Nordics, and Europe); many of the vehicles there were European imports anyway which corresponded with the new side of road driving.

Efforts towards a wider Nordic economic treaty floundered in the late 1950s however due to differing economic priorities and geopolitical priorities. As such, Denmark and Norway had followed the United Kingdom in applying for membership of the European Communities in 1963 due to the strength of trade between the two Nordic states and the UK. This 1963 application, as well as a subsequent attempt in 1967 were both declined with a French veto due to the perceived transatlantic relationship between the UK and USA. In light of this, the Danish Prime Minister (Hilmar Baunsgaard) in 1968 proposed a Nordic version of the EC; full Nordic economic co-operation. Both Sweden and Denmark especially were interested in a full customs union - that is the cessation of internal barriers and a common external tariff), whilst Norway needed capital to continue developing it's infrastructure - as well as providing an opportunity to create a common fisheries policy to "level up" it's coastal communities. Significant numbers of politicians in both Denmark and Norway favoured EC membership over what had become known as "Nordek" (NORD Economic Kommunity"), but the position of du Gaulle as French President proved an insurmountable obstacle; a position entrenched following his success in the 1969 French referendum and with no end likely in the short term it seemed.

As such, with seemingly few other options, Nordek was presented to the wider Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland) for signature; all 4 were existing EFTA members or associates, although the door was left open for Iceland to join later. The Swedish Government heavily backed the proposal (as shown in some of it's commitments). Opinion polls showed Finns had the greatest backing for Nordek at around 50% backing it, and 25% being ambivalent. Questions remained for Finland however, due to the presence of the Soviet Union next door, and Soviet politicians were suspicious. It was in light of this, with continued French vetoing of northern European nations joining the EEC (by then European Economic Community), that additional clauses in the Nordek treaty allowed for the suspension of Nordek if any member country proceeded to later accede to the EEC, whilst the treaty explicitly mentioned that the economic union would have no bearing on member's independent foreign and defence policies. It was explicitly to be a "purely commercial arrangement - not political" as some analysts put it, although some shared commerce rules would inevitably be required. It was an excellent reflection on the shared Nordic mindset that many of these rules could be co-ordinated initially by inter-governmental agreement and implemented by national law, rather than the supra-national political approach taken by the European Community.

President of Finland, Urho Kekkonen had a tightrope to talk in balancing Nordek and Soviet relations.

Either way, the "Treaty establishing a Nordic Economic Community" (later popularly referred to as the "New Kalmar Treaty" in a nod to the historical union between Nordic countries) was signed by the 4 countries in May 1970 (delayed for several months by Finnish-Soviet talks, with their Friendship Treaty extended by 20 years), and later ratified by the national Parliaments. It would establish a full customs union within 10 years between the 4 countries - with a few product/policy areas taking longer, including provisions for agriculture and fishing. Details of Nordek did not preclude any signatory from attempting to migrate to EEC membership, but any such move would likely trigger a swift "guillotine" effect on the Nordek economic links as documented in the treaty itself, in order to protect Finnish interests and allow the begruding acceptance of the Soviet Union next door. Later research during the 20th Century in to declassified material for the time indicated that Soviet acceptance was rooted in a desire to avoid a fully integrated European neighbour; by allowing Nordek to proceed, with safeguards to avoid Finland becoming too entangled, hopefully keeping west/north Europe economically divided at least partly.

Financial co-operation will see the enactment of three funds; general, agricultural and fisheries, for structural improvements and stabilisation in order to modernise markets and industry. Cooperation in industrial policy would be concentrated on areas in which the Nordic countries have important common needs, for example, pollution, health, oceanic research, space research, atomic energy and automation. Negotiations are taking place on the building of a Nordic atomic energy company - of interest especially to Sweden and Finland - on the successful Scandinavian Airlines model. This would see coordination in research, development and use of reactors, as well as the fuel market. The importance of adopting uniform company laws as soon as possible was emphasised, as is also need for uniform rules on government bankruptcy, the protection of patterns, unfair competition and the like.

All this would be administered by the Nordic Ministerial Council - with a member from each of the Nordic Governments, with all decisions to be unanimously, and a committee of officials under them to prepare the decisions and matters of the Council; and everything to start on the 1st January, 1971.

-------------------------------------

Hi all, so this is a redux/ rewrite of my "Nordic Twist to Europe" TL I did back in....2014 it seems. Wow. Except I changed the PoD to 1970, and the original Nordek treaty being signed, which is based on du Gaulle winning his French referendum, therefore not stepping down, and therefore there still being no immediate likelihood of UK/Ireland/Denmark/Norway joining the European Communities.

Last edited: