You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

These United States: the Story of Two Congresses

- Thread starter President Benedict Arnold

- Start date

So why did Spain switch sides?

I saw it as too much to explain and not the focus of the story to mention it. Spain switched sides because of seeming American pressure on their colonial holdings, France being diplomatically closer to the United States than to Spain, Spain being a kingdom among republics, and internal pressure from the Spanish Court, which saw cordial relations with such radical ideals as dangerous to the existence of the kingdom.

Hope that clears things up.

I saw it as too much to explain and not the focus of the story to mention it. Spain switched sides because of seeming American pressure on their colonial holdings, France being diplomatically closer to the United States than to Spain, Spain being a kingdom among republics, and internal pressure from the Spanish Court, which saw cordial relations with such radical ideals as dangerous to the existence of the kingdom.

Hope that clears things up.

Ah. That makes sense. Great TL by the way.

Part XIV: The Monroe Presidency and the American Doctrine

The Election of 1812 is a tangled mess of an event. Henry Dearborn had served his two terms of a mostly popular presidency and his Vice President James Monroe was the favorite of the Federalist Party, despite historically being a Confederationist and sharing few beliefs with the foundings of Federalism. Alexander Hamilton strongly lobbied against him but, having long since lost influence in the party he founded, he was ignored.

James Monroe seemed to have the election locked up before it had even begun. He had strong backing from the largest political party in the United States, he was well liked, and nobody within the party was running against him because they assumed that he would win. It seemed it was going to be a sweep until the Revolutionary arm of the Confederationist Party began to prepare for the election. The Revolutionaries, who would later become well known as the Republicans, first came together to run for the presidency in 1812. Headed by Peyton Randolph, William Henry Harrison, John C. Calhoun, and Henry Clay, the Revolutionary-Confederationists broke with the rest of their party by running a campaign for William Henry Harrison.

At thirty-nine, Harrison was their oldest member and with the reputation as a war hero for the role he played in the Irish Revolution, the Haitian Revolt, and the War of the Second Coalition, he commanded a lot of respect. His youth made people fear his inexperience and the controversial ideas he proposed, such as heavily investing in industry, establishing a national bank, creating a national currency, and expanding the military, were considered hawkish and radically Federalist. These ideas leveled out the population’s adoration of him against the opposition to his ideas. Many believed he would have swept a victory had he toned down his rhetoric during the campaign. Whatever would have happened doesn’t matter, as James Monroe successfully took the presidency in a close race. Rhode Island being called for him was what put him over and made him victorious.

He decided to adopt many of the ideas that the Revolutionary-Confederationists proposed, including the construction of a permanent residence for the president in the form of a mansion in the heart of Philadelphia, right near where the First Continental Congress had met. He also enacted what Harrison had, and the population at large would refer to as the American Doctrine. The Doctrine claimed that the Americas were no longer a land of European colonization, but a land with a people and culture of their own who shall unite and fight back in the face of such colonization. It stipulated that any currently held territories would be allowed, but any expansion of those territories would not be. Although the United States had proven itself strong, that was only due to how far it was from the power centers of Europe. It could easily crush the colonial garrisons of Spain and Britain, but facing a unified European army would be far more difficult. While this declaration would not make the European powers completely cease any colonial expansion, not yet anyway. Britain’s border had not moved beyond the point that it had been set at when the War of the First Coalition ended, but they justified it to themselves by talking about how much open territory there still was in the lands they owned. This would lead to British North America become a very densely populated region consisting of many large towns and sprawling cities.

Among the Federalists, there was much discontent. Many were growing sick of the government’s focus on international alliances and war. They had hoped that Monroe would have brought them in a more neutral and isolationist position, as word had spread of his previous hangups with an alliance with the French.

None of them could have known just how absolutely wrongheaded these assumptions were. In 1813, James Monroe signed the documentation that formalized the borders and membership of the Republican Coalition and its nation’s role in it. The Irish Republic, Dutch Republic, and France were obligated to maintain large navies in the North Atlantic to keep the remainder of the British Navy in check. The Batavian, Rhine, and Helvetic Republics were obligated to maintain large armies to defend against Austria, Prussia, and Russia. France and the Italian Republic both maintained large armies and navies to oppose the upstart Kingdom of Sicily to the south, Portuguese goals in the Mediterranean, and the Ottoman Empire. Spain was considered neutralized due to Berthier’s prominent position in the court. The United States was obligated to have a medium sized navy and a large army, to face off against any force that could be constructed to oppose them in North America.

The Federalists were furious and calls from across both the Constitutional and Confederation Congress demanded that Monroe step down for this. He refused, but under much political pressure, left the Federalist Party in early 1814. This proved disastrous for the midterm elections of the Federalists, with many siding with their now independent president against what they saw as needless hostility. Monroe also spent his presidency trying to include as much existing territory into states as possible, but saw repeatedly roadblocks throughout his presidency.

On March 3rd of 1815, he would lose absolutely all of the power he may have still had, being an independent facing off against the leadership of a party he had left and another party he had refused to join, when the Panic of 1815 happened due to a land market bubble just west of the Ohio bursting. He and his moderate economic plans were blamed for it by both sides. Interestingly, the American people fell into the camp that he did not do enough economically and believed that Harrison’s economic plan would have kept this from happening. In every economic crisis before this, most had simply blamed too much government meddling instead of not enough.

This made Monroe the most powerless president since the beginning of Edmund Randolph’s presidency. With little to do, he spent his time resolving any diplomatic issues, finding any inconsistencies between the leadership of the current government and the Constitutional and Confederationist governments before it and resolving them to the best of his ability. The last year of his presidency helped to create a single united foreign policy for the United States and helped determine the exact standing the government had with governments all around the world.

During his presidency, the Revolutionary-Confederationists grew to dominate their party and changed the official name to the Republican Party. The Republicans were now on the rise, with William Henry Harrison running for president once again. As the election approached, even Monroe, the outgoing independent president, endorsed him.

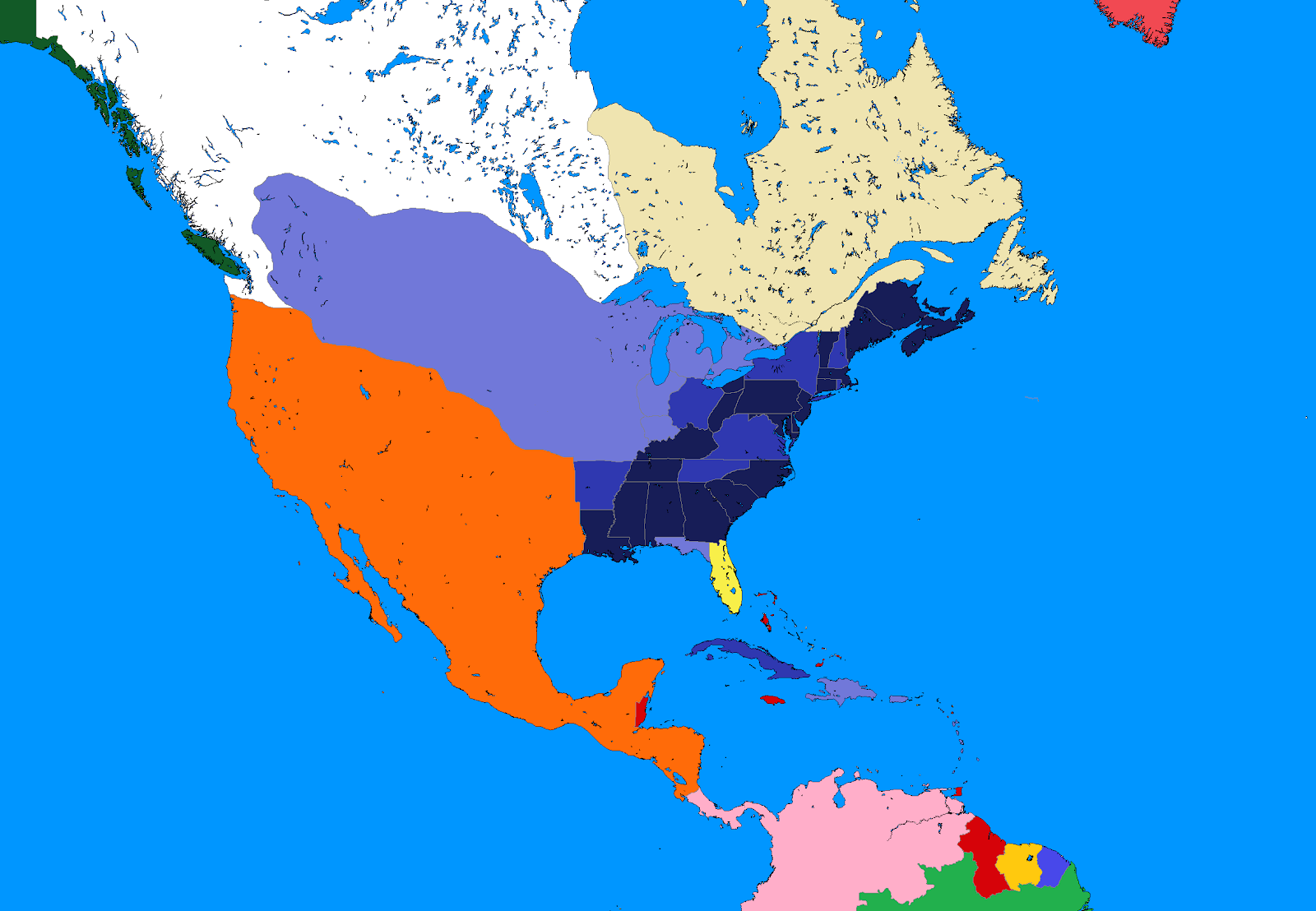

North America in 1816:

I'm so so so sorry about how long this took. A lot of life things got in the way and it took a lot of time to get enough content together for a post. Hope you enjoy and I promise the next one will be sooner.

Interlude IV: British Troubles

For the past decade, Britain was economically and politically in awful shape. They were living through a depression that would not be topped in suffering and ferociousness in any Western nation until the Great Depression over a century later. They had been repeatedly defeated and humiliated on the national stage, losing to the Irish, the French, and the Americans. There were many in Britain who started to believe that the only course of action that could be taken was an overthrow of the government. The only thing that tied the nations that had overcome impossible odds to defeat them were the fact that they were all republics, with no monarch sitting on the throne. A small, tight-knit group of poets, philosophers, and members of Parliament began to hold secret meetings in the basements and backrooms of buildings across London. They called themselves the Neo-Leveler Club and sought to revive the spirit of the Time of Troubles in light of the failing British monarchy. The President of the Neo-Leveler Club was Charles James Fox, with notable members including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Hazlitt, and Henry Richard Vassall-Fox, the nephew of Charles James Fox. Heavily inspired by the Jacobin Club in France, they began plotting their course of action towards a revolution.

In 1808, with guns from Irish smugglers and commanders from the Irish military, the Neo-Levelers began to arm and train a group of nine thousand artisans and farmers who had been facing harsh times due to the economic turmoil of the country. In February of 1809, not long after the weather began to improve, the Neo-Levelers marched on the City of Bristol, which had been hit particularly hard by the depression due to the sudden lack of any trade with Ireland. The Neo-Levelers assumed that the people of Bristol would be on their side as they began proclaiming that a republic built on the power of the people in service of the people shall replace the incompetent monarchy of Britain. They were right and the townspeople gathered around as Charles James Fox declared the Republic of Britain in the middle of Bristol, with himself as acting Prime Minister. He declared that once London was taken, a new parliamentary election where all men could vote would be held, to roaring applause.

The Neo-Levelers then marched towards the nearby city of Bath, where the British military had gotten to first. They had spread the message that these Neo-Levelers were nothing but puppets of the Republican Coalition that would collapse when faced in open battle. They were proven right when the seven thousand Neo-Leveler soldier sent to take Bath were soundly defeated by a young Sir Isaac Brock, and their forces scattered. Brock then marched on Bristol, which surrendered before another battle could take place. All of the leading members of the Neo-Levelers were hanged for the actions, except for Henry Richard Vassall-Fox, who fled to Ireland. He began to go by Henry Callidia-Fox and, became a lifelong advocate for a British Revolution. He traveled through the countries of the Republican Coalition and wrote a great many books, the most notable of which was released in 1834 and was called On the Manner and Form of Revolution, which would be read and reread by revolutionaries across the world for centuries to come. In the book, he gives a detailed account of the military, political, and oratory moves and styles of the great leaders of the Irish, American, French, and Latin Revolutions as well as a day by day account of his own experience in the abortive British Revolution. Although he spent the rest of his life attempting to spark another British revolt, including attempts to recruit British people residing in Northern Ireland. One hilarious attempt was when he tried to recruit a few dozen farmhands and prostitutes from around Dublin and promised them all major positions in government. He had been given a residence by Wolfe Tone just outside of Dublin as soon as he arrived in the country, where he would live until his death in 1840.

Prince Regent George IV believed that the revolt only happened because the monarch in charge of everything was horribly incompetent. He feared that this was only a sign of things to come in a world after King Louis XVI has been executed. George IV, at the age of 49, staged a peaceful overthrow of his father. He declared him incapable of ruling Britain and was then crowned himself as king. He took steps to ensure that his wife Catherine, whom he had separated with over a decade earlier, would not sit as his queen. He introduced a series of bills to Parliament before his not-a-coup that greatly increased the power of the monarchy and limited allowed speech by broadening the definition of slander and significantly increasing the number of potential crimes that do not go to a court of law. While these moves were unpopular with the public, any attempt at speaking out against it was shot down as the talk of mad revolutionaries. At all levels of the military and the government, purges began to root out anybody who could be in favor of a republic or have republican sympathies. Under George IV, Britain became a much harder place to live a free, politically active life.

In 1811, once his rule was firmly established and his wife had died of an unknown illness, George IV married Ekaterina Pavlovna Romanov, the daughter of Tsar Paul I, who was over twenty years younger than him and began going by Catherine upon arriving at the British court. This marriage was significant as with Catherine came exposure of the style of rule of the Russian Empire. Like all monarchs of Europe, George knew about the Russian monarch’s completely unchecked power but never quite understood how it worked. He began to be enticed by the ideas that Catherine only incidentally gave him out of confusion over how Britain was run. Slowly the powers of the parliament would be eroded by the reign of George IV, culminating in 1817 with the creation of the Ministry of Taxation directly under King George IV, taking one of the key powers of parliament away from it. Catherine would also father a son for George IV, who would become Augustus I.

With the British now being a weak power economically, the British monarchy began focusing on military power and conquest abroad to distract its populace away from the increasingly reactionary monarchic regime and the failures that the country had recently seen. With India and Australia being split in half between France and Britain and the United States being the dominant force in North America, the British turned their attention further east, seizing port cities along the coastline of Africa and Southeast Asia and beginning to put pressure on the Qing Empire further to the north. This would come to define British foreign policy for the coming decades, setting up the foundation to what many historians like to call the Second British Empire.

Interlude IV: British Troubles

For the past decade, Britain was economically and politically in awful shape. They were living through a depression that would not be topped in suffering and ferociousness in any Western nation until the Great Depression over a century later. They had been repeatedly defeated and humiliated on the national stage, losing to the Irish, the French, and the Americans. There were many in Britain who started to believe that the only course of action that could be taken was an overthrow of the government. The only thing that tied the nations that had overcome impossible odds to defeat them were the fact that they were all republics, with no monarch sitting on the throne. A small, tight-knit group of poets, philosophers, and members of Parliament began to hold secret meetings in the basements and backrooms of buildings across London. They called themselves the Neo-Leveler Club and sought to revive the spirit of the Time of Troubles in light of the failing British monarchy. The President of the Neo-Leveler Club was Charles James Fox, with notable members including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Hazlitt, and Henry Richard Vassall-Fox, the nephew of Charles James Fox. Heavily inspired by the Jacobin Club in France, they began plotting their course of action towards a revolution.

In 1808, with guns from Irish smugglers and commanders from the Irish military, the Neo-Levelers began to arm and train a group of nine thousand artisans and farmers who had been facing harsh times due to the economic turmoil of the country. In February of 1809, not long after the weather began to improve, the Neo-Levelers marched on the City of Bristol, which had been hit particularly hard by the depression due to the sudden lack of any trade with Ireland. The Neo-Levelers assumed that the people of Bristol would be on their side as they began proclaiming that a republic built on the power of the people in service of the people shall replace the incompetent monarchy of Britain. They were right and the townspeople gathered around as Charles James Fox declared the Republic of Britain in the middle of Bristol, with himself as acting Prime Minister. He declared that once London was taken, a new parliamentary election where all men could vote would be held, to roaring applause.

The Neo-Levelers then marched towards the nearby city of Bath, where the British military had gotten to first. They had spread the message that these Neo-Levelers were nothing but puppets of the Republican Coalition that would collapse when faced in open battle. They were proven right when the seven thousand Neo-Leveler soldier sent to take Bath were soundly defeated by a young Sir Isaac Brock, and their forces scattered. Brock then marched on Bristol, which surrendered before another battle could take place. All of the leading members of the Neo-Levelers were hanged for the actions, except for Henry Richard Vassall-Fox, who fled to Ireland. He began to go by Henry Callidia-Fox and, became a lifelong advocate for a British Revolution. He traveled through the countries of the Republican Coalition and wrote a great many books, the most notable of which was released in 1834 and was called On the Manner and Form of Revolution, which would be read and reread by revolutionaries across the world for centuries to come. In the book, he gives a detailed account of the military, political, and oratory moves and styles of the great leaders of the Irish, American, French, and Latin Revolutions as well as a day by day account of his own experience in the abortive British Revolution. Although he spent the rest of his life attempting to spark another British revolt, including attempts to recruit British people residing in Northern Ireland. One hilarious attempt was when he tried to recruit a few dozen farmhands and prostitutes from around Dublin and promised them all major positions in government. He had been given a residence by Wolfe Tone just outside of Dublin as soon as he arrived in the country, where he would live until his death in 1840.

Prince Regent George IV believed that the revolt only happened because the monarch in charge of everything was horribly incompetent. He feared that this was only a sign of things to come in a world after King Louis XVI has been executed. George IV, at the age of 49, staged a peaceful overthrow of his father. He declared him incapable of ruling Britain and was then crowned himself as king. He took steps to ensure that his wife Catherine, whom he had separated with over a decade earlier, would not sit as his queen. He introduced a series of bills to Parliament before his not-a-coup that greatly increased the power of the monarchy and limited allowed speech by broadening the definition of slander and significantly increasing the number of potential crimes that do not go to a court of law. While these moves were unpopular with the public, any attempt at speaking out against it was shot down as the talk of mad revolutionaries. At all levels of the military and the government, purges began to root out anybody who could be in favor of a republic or have republican sympathies. Under George IV, Britain became a much harder place to live a free, politically active life.

In 1811, once his rule was firmly established and his wife had died of an unknown illness, George IV married Ekaterina Pavlovna Romanov, the daughter of Tsar Paul I, who was over twenty years younger than him and began going by Catherine upon arriving at the British court. This marriage was significant as with Catherine came exposure of the style of rule of the Russian Empire. Like all monarchs of Europe, George knew about the Russian monarch’s completely unchecked power but never quite understood how it worked. He began to be enticed by the ideas that Catherine only incidentally gave him out of confusion over how Britain was run. Slowly the powers of the parliament would be eroded by the reign of George IV, culminating in 1817 with the creation of the Ministry of Taxation directly under King George IV, taking one of the key powers of parliament away from it. Catherine would also father a son for George IV, who would become Augustus I.

With the British now being a weak power economically, the British monarchy began focusing on military power and conquest abroad to distract its populace away from the increasingly reactionary monarchic regime and the failures that the country had recently seen. With India and Australia being split in half between France and Britain and the United States being the dominant force in North America, the British turned their attention further east, seizing port cities along the coastline of Africa and Southeast Asia and beginning to put pressure on the Qing Empire further to the north. This would come to define British foreign policy for the coming decades, setting up the foundation to what many historians like to call the Second British Empire.

Last edited:

I only hope that Britain doesn't remain evil for much longer.

Sorry but that's not the case.

Yay, evil Britain!

On a more serious note, I love this. Keep up the amazing work!

On a more serious note, I love this. Keep up the amazing work!

Sorry but that's not the case.

This makes AE sad.

And wanting revenge against the evil republicans.

Really enjoying this so far. (I bet the Americans are glad they revolted when they did, right?  )

)

And now we've got the Evil British Empire under Dictator-King George IV. I remain hopeful that the Brits will revolt at some point in the future - this can't last forever.

And now we've got the Evil British Empire under Dictator-King George IV. I remain hopeful that the Brits will revolt at some point in the future - this can't last forever.

Part XV: The Rise of the Republicans

The Election of 1816 was one of the most lopsided blowouts in the history of the United States. The election was between the Federalist Party and the Republican Party. The Federalist candidate was Rufus King and, as they attempted to win over those who turned away from the party when Monroe declared himself an independent, a narrative started forming around the leadership of the party compared to their competitors. The Federalists have remained under the increasingly aging leadership that had been in charge since the revolution. On the opposing side was the Republican Party, formerly the Confederationist Party, which seemed to be the antithesis of everything wrong with the Federalist Party. Their leadership was young, inspiring, and dynamic, made up of war heroes and representing the cutting edge of political philosophy globally. They believed in the ideals of liberty and fraternity that were espoused in the European revolutions and wished to radically alter the very structure of American society. The only major break they had with the European powers politically was their neutral opinion on slavery. As students of the French and Irish Revolutions, they were militaristic and patriotic to the core, and their foreign policy represented that. William Henry Harrison, who stood as the Republican candidate for president, gave rousing speeches in opposition to the continued existence of the British and Spanish empires in North America. He preached that these territories should not be conquered by the United States like European imperialists, but made into independent republics that could forge their own path.

When the election finally ended on December 4th, Harrison had won in every single state except for Vermont, which preferred King’s isolationist rhetoric as it continued repairing the damage done during the Great European War. Harrison won more electoral votes than any president elect in United States history up until that point and would not be surpassed by another president elect until the Election of 1860, almost fifty years later. Harrison was the first president who was not a Founding Father. He was the first president to be too young to remember British rule, being born in 1773. His victory represented a new era for the United States. The Founding Era, marked by conflicts between Federalists and Confederationists and figuring out how the United States will run was over. The Republican Era, marked by continent-wide revolution and internal reform had begun.

Harrison said as much in his Inaugural Speech in Philadelphia. He proclaimed: “The United States was the birthplace of revolution and shall once again be its home in the New World. It is our country’s divined purpose to topple the old European empires on the American continent for all of the peoples of America, whether or not they be of European blood. The British and the Spanish have proven that their leaders are turncoats and fools, just like the French monarchy before the Great Revolution brought about much needed change. As has happened in France and Germany and Italy and Ireland, so to will it happen in Canada and New Spain and Brazil.” While independence for all of the Americas was a major focus of his time and effort, he also had a robust domestic policy. After nearly twenty years of work, suffering technological setbacks, lack of funds, and a great deal of other annoyances, Robert Fulton finally revealed his La Flotte de L'Avenir. This was by far the most modern fleet the world had ever seen. Powered by steam, the ships would never bow to the whims of the wind again. As Fulton faced many technological hurdles to bring his steamships to completion, he busied his men with making intricate carved doors and walls, grand cabins for the officers of the ship, and a drainage system to keep the decks, cabins, and lower levels relatively dry. This fleet was revealed to the world in early 1815 and a handful of the eight hundred ships were toured across the Republican Coalition to represent the grandeur and power of the forward looking French. Harrison was able to visit and tour one of these ships when it was docked in New York City. He was so inspired by the engineering that he made one of his major campaign promises to create a three hundred ship fleet of similar status.

This was part of a larger domestic plan to embrace the emerging industrialization of France. Harrison was unable to get the Confederation Congress to jointly fund industry, although New York and Franklin both broke rank to begin doing so, but the Constitutional Congress did agree to it. Industrialization began with a focus around Philadelphia, Newark, New Haven, Baltimore, Charleston, and Raleigh. While this move garnered very little excitement short term, it would have massively positive effects later on.

Harrison, having emerged from the Confederation Congress, began to privately lobby for new states to join the Confederation over the Constitution. No new states had been added to the Confederation since Vermont over twenty years ago, which had eventually switched to the Constitutional Congress. With this unofficial support, Harrison was able to get the states of Michigan, Arkansas, and Cuba introduced as Confederation states during his first term, with Arkansas joining in 1817 and Cuba and Michigan joining in 1818. This brought much anger to the Constitutional states, due to it having been so long that it seemed like the Confederationists would remain those five states. They also opposed the seeming bias of the presidency but, like the president’s support for the matter, their disgruntlement was also in private.

In regards to the revolutions of the American continent, Harrison had quite a plan. He knew that, like in the Irish Revolution, the best the American people could do was serve a supporting role as the locals pave their own path and decide what independence, freedom, and republicanism really meant for them. That did not mean that Harrison could not guide them down this path. There had been several major attempts at sparking a revolution by Creole leaders of the colonies, who opposed Spanish rule. Every one of these attempts was a failure and in almost every case, the defeated revolutionaries fled to the United States. There was quite a community of wealthy failed revolutionaries like Francisco de Miranda, Jose Maria Morelos, Antonio Josede Sucre, Jose de San Martin, and Simon Bolivar growing in New York City. Harrison invited these men and others down to the Presidential Mansion in Philadelphia to discuss how to proceed with each region’s revolution. The result was a thorough plan of action that became known as the Great Continental Mission.

The goal of the mission was simple: revolution and independence. The pathway towards revolution was far more complicated and greatly depended on the region. In Canada, the plan is to agitate in favor of the French-speaking Catholic populace against their British overlords. Many political figures are considered, but it is eventually decided that Louis-Joseph Papineau would be the leader of the revolution there. Papineau had been exiled after attempting to begin a rebellion in protest to George IV’s seizure of the crown, which was seen as an illegal move by many, he was forced to flee to the United States. He harbored a deep seated dislike and distrust of New Yorkers and New Englanders due to the American invasion of British North America when he was young, and the Siege of Montreal in particular. This lead him to chose to move to Philadelphia as opposed to Boston or New York City, where he was close at hand when Harrison and the revolutionaries began to plan the Canadian Revolt.

The next one was the Mexican Revolt. Mexico was the chosen name of those who wished to distinguish their ideal of the country from New Spain. The Mexican people were deeply religious, so the church would have to be involved on a more fundamental level. The Jesuit faction of Catholicism was far more popular in Latin America than it was in Europe, so the revolutionaries came in contact with the Superior General of the Jesuits, currently Tadeusz Brzozowski was residing in Paris once the Concert of Europe, the European answer to the Republican Coalition, decided that the order stood opposed to the continued power of the monarchies.

At its founding in 1811, the Concert only included Britain, Sicily, the Austrian Empire, Prussia, the Russian Empire, Portugal, and Denmark but Norway, Sweden, the Ottoman Empire, Sicily, and Spain joined over the course of the following year. Spain joined after the death of Berthier in 1815 under suspicious circumstances, leaving the young Ferdinand VII surrounded on all sides by reactionary forces. This meant that no neutral power existed in Europe, everybody was either pro-revolutionary or anti-revolutionary. The fear of republican uprisings sponsored by France or the United States lead these kingdoms and empires to become considerably more oppressive, going after any and all groups that could be considered potentially subversive. Merchants who used to be able to freely operate became closely monitored and attached to the government. Religious or political groups that had operated for decades and centuries that did not directly serve the monarch, or in Catholic countries, the Pope, despite his mild support of the republicans, were either banished or forced to disperse. The Jesuits were banished and fled to one of the few places and Europe they could go, France. France welcomed in those who had been forced out of their countries with open arms, planning on using them to subvert and overthrow these empires across Europe. In 1817, their equivalent of the Great Continental Mission was forming, which would come to be called the Great European Mission. The Great European mission would eventually be in favor of Polish, Serbian, Hungarian, Greek, Sardinian, and Catalan independence, which would mark the major wars of Europe during the 1820s.

Brzozowksi and the Jesuits were persuaded to back revolution in Latin America, giving them a base of power in Latin America. With the Pope’s support, the Jesuits began to help support the overthrow of European rule in the Americas. Combined with the alliances made between the revolutionaries and the Creole elite, this formed a strong basis for revolution across all of South America.

In 1818, four simultaneous revolts succeeded at taking over the region they started. They began at Montreal in Canada, Merida in New Spain, Cartagena in New Granada, and Buenos Aires in Rio de la Plata. The leader of the Canadian Revolt was Papineau, the leader of the New Spanish Revolt was initially Barragan, but he was soon superseded by Santa Anna, the leader of the New Granadan Revolt was Domingo Caycedo, and Mariano Moreno in Rio de la Plata. The revolts that were attempted in Peru and Brazil failed. The successful revolts quickly swept across their nations and news spread around the world. The United States had helped spark independence revolts across the continents. Any reaction would have them invoke the American Doctrine. The Spanish were in a particularly terrible situation, bordering Spain, having had close ties with the United States, and having three successful revolts going on in their territories. The revolts would be sporadic and violent and would take over a decade. Whether they were successful at securing these countries independence or not would mark Harrison’s legacy, and the legacy of the Republicans.

Last edited:

This next update contains many maps (sorry they took so long). I would just like to address that these maps aren't entirely accurate, seeing as how a lot of territory that was not colonizable at the time is shown as being part of a country. This is supposed to show what nations claim belongs to them (with no overlaps shown) and what will eventually end up as a part of one country or another. There are so many islands I did not paint because I have work and homework and it just got to be too much.

Interlude V: Latin Republics and the Republican Coalition Overview

As of 1820, North America was almost entirely dominated by revolutionary republics. The United States had been standing for nearly fifty years now, and their new allies in the Republic of Quebec and the Republic Mexico were hellbent on catching up with their shared neighbor in many ways, but mainly in economics and prestige. The United States had a much bigger population that Mexico or Quebec and had the advantage of decades of self-rule and had not been suffering under mercantilism for a long time. This put those countries at a disadvantage but also gave them a hunger to overcome these ills and compete against economic powers.

Mexico: Mexico was being lead by President and Commander-in-Chief Santa Anna, who styled himself after George Washington and Lazare Hoche, seeing himself as a guardian against tyranny from either aristocrats or the masses. Santa Anna was young and came to be the leader of the Mexican Revolution through sheer force of will and wit. He would become legendary for the changes he made in Mexico, including the integration of indigenous peoples, the industrialization of central Mexico, and how he maneuvered Mexico into sitting alongside France, Italy, the United States, and, later, Rio de la Plata as the leading figures of the Republican Coalition. Santa Anna would rule as a republican dictator in Mexico, much like Hoche, until his health began to fail in 1849. He finished transitioning the nation into a republic by 1853, won the first presidential election the next year by almost ninety percent of the vote, and then died in 1855. In many ways, Santa Anna is believed to have embodied Mexico itself and his name is nearly synonymous with the rise of the great nation.

Quebec: Quebec was first lead Papineau but after he was assassinated by a British loyalist in 1822, no firm leader emerged. This seems to have been what allowed Quebec to quickly transition to a parliamentary democracy, where dozens of representatives made decisions from the bottom up as opposed to those decisions being imposed from the top down.Quebec was a smaller nation that the United States expected to apply for statehood at any time, with the provision in the Confederation Congress still explicitly stating that they would be automatically approved. Quebec never did and would stand on its own as staunch ally to the United States for the following century.

Gran Colombia: The leading power of South America upon independence, Gran Colombia in many ways was the successor of the French Revolution than any other. It radically reshaped how the people saw themselves and sought to radically change their society. Gone was the divisionary cast system that was only really overcome in Gran Colombia and Saint-Domingue, one of their inspirations. They did not perfectly eliminate this, with slavery remaining legal and common, all freemen were treated as equals. Besides Quebec, Gran Colombia was diplomatically far closer to the United States than any other country.

Rio de la Plata: While many could see Rio de la Plata’s small population upon independence as a weakness, they played it as a strength. The leaders of the revolution were able to shape a stable system with strong republican traditions simply because they had to organize such a small amount of people. The fighting throughout most of the rest of Latin America was very violent, but Rio de la Plata was spared much of this, with most of their losses coming from assisting their neighbor’s revolts. It is not hard to see why the country emerged as one of the leading republican nations.

Spanish Peru: Although it held out as a loyalist stronghold in 1818, Peru would gain its complete independence within a decade. Due in no small part to the lack of international support during their revolution, it was much messier and bloodier than their neighbors to the north and the south. Peru sadly experienced many more coups and rebellions against their government than most of Latin America suffered, leading to it ending up on the lower end economically.

Portuguese Brazil: Portugal was initially excited by the events that were transpiring in Latin America. The revolt on their own territory failed and all of their neighbors were now young republics attempting to gain control of their own territory. Portugal believed they could turn them into colonies until the Brazilian Revolutions began to break out in 1823. The entire colony was torn apart as local revolts began to form their own governments, eventually splitting the colony into five nations, all allied against a Portuguese invasion that never came.

Guyana: Despite its divided nature between the British, French, and Dutch, there was an attempt to make Guyana gain independence as a unified nation. It ended horribly, but there was an attempt. The territory would be held by their European masters for over one hundred more years and would be the only European presence on the mainland of the continent that would survive the decade.

Rough map of Europe, just for fun:

I am not going to get into the function of each of the countries of Europe or what they spell for the rest of the world, so instead I am going to talk about the Republican Coalition.

The Republican Coalition is an intragovernmental alliance of democratic nations in Europe and the Americas. The coalition's primary goals are to defend each member's sovereignty, especially against a monarchic opponent, and to spread republican revolutions even further. The key members of the Republican Coalition are France, the United States, Italy, Mexico, and Rio de la Plata. While every member has an equal say in theory, these five the ones who really wield all of the power by the 1830. While the coalition was a strong unifying force in the early 1800s, tensions between individual nations would eventually lead to it being sidelined throughout the 1840s and finally disbanded in 1868. There have been "successor organizations" in the form of alliances between republican nations formally calling it the Republican Coalition, but there is no continuous line between this revolutionary organization and any of the later ones.

Interlude V: Latin Republics and the Republican Coalition Overview

As of 1820, North America was almost entirely dominated by revolutionary republics. The United States had been standing for nearly fifty years now, and their new allies in the Republic of Quebec and the Republic Mexico were hellbent on catching up with their shared neighbor in many ways, but mainly in economics and prestige. The United States had a much bigger population that Mexico or Quebec and had the advantage of decades of self-rule and had not been suffering under mercantilism for a long time. This put those countries at a disadvantage but also gave them a hunger to overcome these ills and compete against economic powers.

Mexico: Mexico was being lead by President and Commander-in-Chief Santa Anna, who styled himself after George Washington and Lazare Hoche, seeing himself as a guardian against tyranny from either aristocrats or the masses. Santa Anna was young and came to be the leader of the Mexican Revolution through sheer force of will and wit. He would become legendary for the changes he made in Mexico, including the integration of indigenous peoples, the industrialization of central Mexico, and how he maneuvered Mexico into sitting alongside France, Italy, the United States, and, later, Rio de la Plata as the leading figures of the Republican Coalition. Santa Anna would rule as a republican dictator in Mexico, much like Hoche, until his health began to fail in 1849. He finished transitioning the nation into a republic by 1853, won the first presidential election the next year by almost ninety percent of the vote, and then died in 1855. In many ways, Santa Anna is believed to have embodied Mexico itself and his name is nearly synonymous with the rise of the great nation.

Quebec: Quebec was first lead Papineau but after he was assassinated by a British loyalist in 1822, no firm leader emerged. This seems to have been what allowed Quebec to quickly transition to a parliamentary democracy, where dozens of representatives made decisions from the bottom up as opposed to those decisions being imposed from the top down.Quebec was a smaller nation that the United States expected to apply for statehood at any time, with the provision in the Confederation Congress still explicitly stating that they would be automatically approved. Quebec never did and would stand on its own as staunch ally to the United States for the following century.

Gran Colombia: The leading power of South America upon independence, Gran Colombia in many ways was the successor of the French Revolution than any other. It radically reshaped how the people saw themselves and sought to radically change their society. Gone was the divisionary cast system that was only really overcome in Gran Colombia and Saint-Domingue, one of their inspirations. They did not perfectly eliminate this, with slavery remaining legal and common, all freemen were treated as equals. Besides Quebec, Gran Colombia was diplomatically far closer to the United States than any other country.

Rio de la Plata: While many could see Rio de la Plata’s small population upon independence as a weakness, they played it as a strength. The leaders of the revolution were able to shape a stable system with strong republican traditions simply because they had to organize such a small amount of people. The fighting throughout most of the rest of Latin America was very violent, but Rio de la Plata was spared much of this, with most of their losses coming from assisting their neighbor’s revolts. It is not hard to see why the country emerged as one of the leading republican nations.

Spanish Peru: Although it held out as a loyalist stronghold in 1818, Peru would gain its complete independence within a decade. Due in no small part to the lack of international support during their revolution, it was much messier and bloodier than their neighbors to the north and the south. Peru sadly experienced many more coups and rebellions against their government than most of Latin America suffered, leading to it ending up on the lower end economically.

Portuguese Brazil: Portugal was initially excited by the events that were transpiring in Latin America. The revolt on their own territory failed and all of their neighbors were now young republics attempting to gain control of their own territory. Portugal believed they could turn them into colonies until the Brazilian Revolutions began to break out in 1823. The entire colony was torn apart as local revolts began to form their own governments, eventually splitting the colony into five nations, all allied against a Portuguese invasion that never came.

Guyana: Despite its divided nature between the British, French, and Dutch, there was an attempt to make Guyana gain independence as a unified nation. It ended horribly, but there was an attempt. The territory would be held by their European masters for over one hundred more years and would be the only European presence on the mainland of the continent that would survive the decade.

Rough map of Europe, just for fun:

The Republican Coalition is an intragovernmental alliance of democratic nations in Europe and the Americas. The coalition's primary goals are to defend each member's sovereignty, especially against a monarchic opponent, and to spread republican revolutions even further. The key members of the Republican Coalition are France, the United States, Italy, Mexico, and Rio de la Plata. While every member has an equal say in theory, these five the ones who really wield all of the power by the 1830. While the coalition was a strong unifying force in the early 1800s, tensions between individual nations would eventually lead to it being sidelined throughout the 1840s and finally disbanded in 1868. There have been "successor organizations" in the form of alliances between republican nations formally calling it the Republican Coalition, but there is no continuous line between this revolutionary organization and any of the later ones.

Part XVI: Internal Affairs

In 1819, the country was riding high on the successes of the Republicans. Within only a few years, the number of factories in the United States had increased exponentially and his centralization and expansion of the national banking system was making everybody richer beyond their wildest dreams. It was a time of optimism and Harrison’s popularity absolutely soared. Some textbooks claim that Harrison’s popularity was around 90%, higher than George Washington’s 75% ever was, but there are no reputable sources on this topic. There were many local newspapers that held polls from among their readers at the time, but that’s not even close to a proper analysis. Nevertheless, there seemed to be a consensus, even among those who had opposed Harrison, that he was good for the country. He had lead begun military conflicts across the entirety of the American continents, but the United States was not directly suffering any consequences from it. Britain and Spain had some nasty denunciations to give, but they were not on friendly terms with the United States to begin with and could hardly do anything against the United States, with its massive standing army on a faraway continent and their close alliance with France, the premier army and navy power of the world. There is little doubt that the Found Fathers who were still living were happy with how the country that they had fought to create turned out so far. It was a prestigious country that truly deserved its spot among the leading revolutionary powers in the world.

Now imagine the shock the nation felt when William Henry Harrison announced that he would not be seeking reelection in 1820. Publicly, Harrison simply wished to recreate the Army of American Patriots to help fight for the Latin Republics and saw it as dishonorable to create such an organization and not lead it himself and fight on the frontlines himself, despite his limp. Privately, Harrison had grown to hate the confines of politics and political life. He missed the adventurous times of the Irish Revolution and wished to relive those days in Quebec or Gran Colombia. Many across the political spectrum applauded this and saw this as a sense of honor and trueness of character that really exemplified the ideals of the Republicans. Harrison had an easygoing final year in office and was one of the few presidents until that point in history who left with there being few within the government who did not support him.

The Republican who ran to replace Harrison was his political ally and close friend Peyton Randolph. The young Randolph was often seen as the most politically savvy of the Republicans and often came across as their leader, which made Harrison’s position as their candidate for president perplexing to some. From what historians can gather, Peyton Randolph did not wish to be the first Republican to run for president due to his father having been president. He wished for the most important part of the first Republican Administration to be its philosophy and how it approached politics, not how the president was stacking up compared to his now deceased father. With the success of Harrison and his endorsement, Randolph ran an incredibly easygoing and positive campaign. The only criticism one can have about Randolph’s campaign is it was not nearly as revolutionary or inspiring as Harrison’s because it basically boiled down to we should continue doing what we have been doing for the past four years because everything’s been great. Randolph’s main competitor, who was once again Rufus King, reportedly conceded to Randolph the day before the election’s tally was actually counted. Randolph had lost in the states of Vermont, Erie, and New Jersey thanks to heavy campaigning by King, but had won in every other won. In fact, every district in the Confederationist Congress’s states had been one by a Republican except for one in New York.

As Randolph took office, Harrison kept true to his word and lead the reformed Army of Patriotic Americans down to Gran Colombia to assist their revolution. Interestingly, it seems as though every major change in William Henry Harrison’s political views came about from him being on campaign. His campaigns in Ireland and on the island of Hispaniola shaped much of the political philosophy he brought to his first term as president. When Harrison arrived in Gran Colombia, this trend continued and in a direction that was radical even for the Republicans. Harrison saw the active breakdown of slavery and racial barriers while he was in Gran Colombia. This was a systematic, revolutionary attempt to rid the country of such practices and prejudices. It was at this point that Harrison became something entirely separate from what his colleagues were and something that was very politically unpopular in the United States. He became an abolitionist. He had his own slaves freed while he was still in Gran Colombia and abandoned his original plan to simply fight there until the tide was in their favor before moving on, remaining there until 1823, when the war was virtually won there. Harrison had originally planned to spend the next decade assisting the new republics to win their wars and then establish themselves before either returning to the Confederation Congress or simply retiring, but now he had a mission and a goal. He wished to end slavery in the United States. He decided that the only avenue with which he could achieve this would be to regain the office of president. There had never been a nonsequential presidency before, but Harrison knew that if anybody could do it, it would be him. He put these plans on the backburner for now, opting to focus on fighting alongside the Colombians, followed by the Platens and then the Peruvians and Brazilians.

Back in the United States, Peyton Randolph’s presidency was getting off to a rougher-than-expected start. The Federalists had managed to gain a majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate of the Constitutional Congress, largely from most voters showing up to cast their vote in favor of Randolph and then leaving the down ticket boxes blank. John Quincy Adams, the son of Revolutionary John Adams, became the outspoken unofficial leader of the Federalists and his strong positions would force Peyton Randolph to compromise on many policies, especially regarding restrictions on trade and expansionism. Adams called for the remaining territories in the United States to be turned into states before anybody could really consider taking even more land. Roughly half of the land controlled by the United States was made up of territories and Adams saw that as an injustice, despite the low population of American settlers in these lands. Peyton Randolph came to agree and would encourage state constitutions be written up by these nations, perhaps only to get it all over with so he could begin his grand plans of American expansion. Instead, this brought the political issues of the day to the forefront and would end up creating yet another crisis for a nation that was essentially formed by them.

There was a distinct cultural, economic, and political difference between states that generally fell under the terms Northern and Southern. Northern states were lead more by the middle class, were industrializing, and had a strong focus on trade and profit. Southern states were ruled by an aristocratic class of large landowners who often held massive slave plantations and cared little for the desires of the lower classes. This geographic divide of this political and cultural divide was generally, but not entirely accurate. The two standout examples of states that are “misplaced” geographically are Alleghany and Franklin. Alleghany has all of the telltale signs of a Southern state, with a large slave population and a tiny number of landowners controlling much of it, while Franklin has more in common with New England in demographics than with their numbers on all sides, with a miniscule slave population, a budding industry, and a political system dominated by the middle class. As one heads further west, these lines are even more blurred. The originally proposed state of Illinois just to the west of Columbia really drives that point home. The northern parts of the region were very Northern, while the southern parts were very Southern. The reason for this was that most of the people in the Southern area were migrants from nearby Kentucky and the people in the northern region were mainly from Toronto and neighboring Columbia. The middle was a confused mixture of it all, with the difference often just being town to town or even neighborhood to neighborhood. While the southern part of the state wished to go one way and the northern part wished to go another, the middle was a mess of allegiances and beliefs. It was finally agreed upon by the two Congresses that this was a problem that had to be fixed if the United States were to add any new states. The issue became such a large part of the conversation, that no other states were even being considered until this was resolved.

In 1821, the answer finally came in the form of ignoring what the locals wanted and just drawing a largely arbitrary line between what would be northern Illinois and what would be southern Illinois. Neither of these states would keep the name Illinois, as the northern part would come to be named Dearborn, after President Dearborn, and the southern part called Cahokia, after the Native American name for the region. The border regions of northern Cahokia and southern Dearborn were a mishmash of people who would prefer to be on the opposite side of the border. This tension would contribute greatly to the polarization of Cahokia and Dearborn, which would set the tone for the debate regarding the rest of the territories. Cahokia and Dearborn were both added to the Confederation Congress in May of 1821. When the hostilities settled a little bit, Missouri and Wisconsin would both be added at the same time in June of 1823 to the Constitutional Congress. This began the general precedent of adding in states two at a time, one politically Northern and one politically Southern, switching between them joining the Constitutional Congress and the Confederation Congress. This precedent would be immediately broken by the addition of Toronto as a state in the Constitutional Congress only a month later.

The total number of states to thirty-three. There are ten Confederationist states and twenty-three Constitutional states. There are seventeen Southern states and sixteen Northern states. The states, by the date they officially joined the Union under the current three branch system are: Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, South Carolina, North Carolina, Erie, Kentucky, Maine, Tennessee, Alleghany, Vermont, Alabama, Mississippi, New York, Virginia, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Franklin, Columbia, Acadia, Nova Scotia, Michigan, Arkansas, Cuba, Dearborn, Cahokia, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Toronto. As of right now, the United States feels as though it is in a good place but the next few decades will see strong expansionism, military exhaustion, and political polarization.

Last edited:

Part XVII: The Truest Patriots

Most of the rest of President Peyton Randolph’s first term was surprisingly uneventful. With him being a moderate regarding slavery, being from the South but with ties to the North, and being well known for coming up with compromises that pleased as many people as possible, a far cry from his supposed showing at the peace talks near the beginning of the century. His vice president, Oliver Wolcott Jr., was a former Federalist from Connecticut and helped make his administration feel American as opposed to just Southern or Republican. There are many reasons as to why he is considered one of the Great Presidents in American History, he spent most of his time overseeing industrialization and continued prosperity for a country that had seen nothing less than outstanding national success since its inception, with the bumps along the road only helping them along thus far.

Peyton Randolph easily won reelection, with those opposed to him being divided between two unnoteworthy candidates. Randolph played a more active international role in his second term, having focused on internal development on the homefront for his first. By this time, the only ongoing conflicts were in Peru and the Brazilian countries. Two competing Brazilian majority revolutionary armies, one trained in Gran Colombia and the other in Rio de la Plata, lead the invasion of Brazil which began in 1822. They ousted the colonial administration, but failed to hold the land together, even with strong international support from the rest of the Americas. The countries that emerged are: the Republic of Para, the Domaran Republic, the Republic of Bahia, the Riograndense Republic, the Republic of Brazil, and the Cisplatine Republic. The Republican Coalition let in most of these countries as members, excluding the Domaran Republic and the Republic of Brazil for a time due to how neither recognized any of the other republics as sovereign nations and claimed control of the entirety of their territory. After the war was one, Harrison spent nearly a year residing in Salvador, the capital of Bahia.

In Europe, there was growing pressure to begin revolutions to tear apart the Concert of Europe and help the Republican Coalition gain control of what is considered to be the entire Enlightened World. All of the attempts in the 1820s failed, with the biggest incident being the failed Hungarian Revolution of 1825, where over six hundred people died. President Randolph was frustrated by these failures and focused a lot more attention on shadowy attempts at organizing revolutionary groups in Europe. This helped to form the DPN, the Duces Populi Novarum, which translates as: the Leaders of the Revolutionary People. The DPN was one of the first modern intelligence agencies and was very controversial with the public. It would be shut down and restarted several times throughout the following century.

In late 1826, internal tensions began to rise as several scandals regarding the Cahokia-Dearborn border began to come out. Reportedly, several members of the committee that drew up the border were bribed to include towns on one side or the other. The only factual documents that have ever come forward about this stated that the committee members were simply in contact with local mayors and businessmen who made their case for their town belonging on one side or the other for economic, rather than political or cultural, reasons. The issue came from the fact that this information was generally given when these committee members were residing in the mansion of their lobbyists, eating luxurious feasts and maybe even hiring some prostitutes.

No matter the facts, the scandal was massive and lead to multiple riots and mass protests across those two states and the rest of the country. People were furious and the blame was generally be aimed at the Republicans, due to most members of the committee being from their party. They lost many seats in that election. Peyton Randolph’s approval was drying up due to his lack of even acknowledging the scandal for the first couple of months.

Internal tensions in the United States were interrupted by an event that would shake the nation to its very core. It began in Alleghany, where a group of seven wealthy men began to hold meetings in a parlor. These men were, Thomas P. Warrington, Elliot Christianson, Robert John Johnson, Martin Presley, Alfred M. Schwartz, Preston Quincy Greene, and Frederick Hartford. These men held meetings every Tuesday and Saturday night in Preston Greene’s parlor where they started by discussing local news and local politics, but over time it grew to be so much more. Preston Greene was a fan of Thomas Jefferson and was the staunchest pre-reform Confederationist that the world had ever seen. He and all of the other men except for Robert John Johnson were part of the Classic Confederationist Party, which began in Erie but took off in popularity in Alleghany. The Classical Confederationist Party held a plurality of seats in the Alleghany state legislature and held enough seats for the Republican Party to have to caucus with them to hold a majority, despite their vastly different political beliefs and ideologies, they both hated the Federalist Party.

In 1825, Preston Greene began to become far more radical. He had begun to read the writings of Henry Callidia-Fox on the failed British Revolution. In the writings, Calli-Fox, the pseudonym he often used at the time, showed open disgust and discussed at length about the injustice of the rule of King George IV. Preston Greene took these lessons to heart, but in his mind the President of the United States was no different than King George IV of Britain. You see, Preston Greene’s father may have been a landowner from South Carolina and his mother was the daughter of a leader of the Whiskey Rebellion who had been pardoned. This seems to have formed Greene’s political beliefs, supporting the rights of landowners and eventually coming to oppose the concept of the executive. He shared these beliefs at the meetings held in his parlor. They were presented moderately at first, as he himself was more moderate, but became more extreme over time as he became more radical.

By early 1827, the seven very wealthy landowners who met in Preston Greene’s parlor were a small secret society that called themselves the Truest Patriots and were hellbent on bringing radical change to the United States. They were not immediately violent, Elliot Christianson wrote a series of papers in the style of the Anti-Federalist Papers called the Anti-Federal Papers. The main focus was on the political scandals and arguing that the Republicans today were no different than the Federalists of old. These papers did not sell well because people thought they were reprints of the old Anti-Federalist Papers. Disheartened, the Truest Patriots began turning to more radical measures.

Sixteen American men who had fought in the Quebecois War of Independence and now lived on the northern border of Missouri were first contacted by the Truest Patriots in March of 1827. They were well known for their raids on small towns throughout Missouri, Dearborn, and Cahokia. The local law saw these men as ruffians and nicknamed them the Penniless Bandits. They were seen as violent, immoral robbers and nothing more. That would all change.

The Truest Patriots hired the Penniless Bandits to kidnap President Peyton Randolph when he visited St. Louis, Cahokia, the capital of the state, in an attempt to show support and solidarity with those upset with the political scandal. The Penniless Bandits were to stay in a warehouse owned by Alfred Schwartz and, in the middle of the night, abduct Randolph from the guest room of the Governor’s Mansion, bring him to that warehouse, and from there transport just over the border into Missouri, where they could hide him on their home turf. Little is known of their plan from there, but it appears that they believed that with the president missing, they could come forward and use him as a hostage against the federal government to institute their demands about governance. Many who have written on the Truest Patriots have painted a picture of these men as absolute lunatics, but it really seems that they were just ignorant of how politics actually worked. None of them ever held any sort of public office or seemed to have any knowledge of politics outside of political theory, from a book focusing on a king, and their discussions with one another.

On the night of the kidnapping, the Penniless Bandits broke into the Governor’s Mansion by smashing a window in the dining hall. Governor Daniel Pope Cook was awoken by the noise and went downstairs to see what had happened. He started the Penniless Bandits as they were coming through the window one by one. By the time he got down there, five or six were already inside, guns in hand. Blue-Eyed Jack, the youngest member of the group, was startled by the governor and shot him without thinking. He collapsed to the ground screaming and Tall Benny shot and killed him after failing to quiet him down.

Peyton Randolph had almost certainly heard the noise and had apparently barricaded his room by the time the Penniless Bandits got upstairs. After failing to get the door more than a couple of inches open, they were apparently wildly shooting into the room. It is not known how many shots they fired, but it is known that one of them had hit President Peyton Randolph in the neck, killing him. Three servants of the household were also killed either before or after the murder of President Randolph. Thankfully, his wife and children were not traveling with him and were not in harm’s way. Cook’s own wife had successfully hid under her bed once she heard gunshots.

By the next morning, on April 5th of 1827, the news was out about Peyton Randolph’s death. A militia was almost immediately raised in St. Louis to try to hunt down the killers, who were soon discovered to be asleep in Schwartz’s warehouse. The militia, which looked more like an angry mob, murdered all except for Blue-Eyed Jack and Limping Lenny, due to one being a boy and the other a cripple. They were both arrested and their accounts of the event in court are two of the only sources of information we have. Blue-Eyed Jack was hanged for his direct involvement in the murder of Governor Cook and Limping Lenny died two years into his lifelong prison sentence.

When news reached the Truest Patriot that their kidnapping schemed failed, most of them immediately tried to flee the country. Martin Presley, who claimed in court to have some reservations about the whole plan, would put a stop to it by reporting to the local law enforcement and confessing to his involvement. All of the conspirators except for Thomas Warrington were caught by the law enforcement before they could even leave the state. Warrington was caught in the City of Toronto and sent back to Alleghany to face his charges. All of them besides Martin Presley were hanged. Presley was sentenced to some time in prison that no official record exists of. He lived out the rest of his life in general obscurity and died in 1853.

There was much uncertainty about what to do now, as the precedent of the Vice President of the United States becoming the President of the United States was a tradition that began here and now. Vice President Wolcott was in Baltimore when he received the news. Politically, it’s quite telling that he first went to the Confederation Congress all of the way in New York City then to the Constitutional Congress in nearby District of Washington to ask for permission to be sworn in as President of the United States. Both Congresses approved, barely, and Oliver Wolcott became the first president to succeed one who had died. The country was in a state of mourning that would last for the next few years with national and international leaders, such as Hoche, would openly mourn the loss of “a great and heroic leader” and “one of, if not the best President the United States had even seen.”

Last edited:

It's a good update, but the bold seems to be a copy of the section above it.

~snip~

Edit: Problem solved!

Last edited:

It's a good update, but the bold seems to be a copy of the section above it.

I knew it looked way too long.

Thank-you for pointing that out.

I'll edit my post and cut out the massive post so it doesn't clog up the page.I knew it looked way too long.

Thank-you for pointing that out.

Interlude VI: Rhineland Strong

The Rhineland Republic is one of the most important states to emerge during this period in world history. Based out of Stuttgart, it was originally only a small sister republic to France during the Coalition Wars, also called the Great European Wars. When Hoche took over, he more or less ended the exploitation of the sister republics by France, giving them the resources needed to govern in their own right. Many say he went to far with the German territories, as he allowed the disparate republics to unify behind one single government. He justified this move, which is almost universally viewed as the biggest political blunder of his career, with this famous statement: “Every culture, every distinct group of people has the right and duty to form a government to governor themselves as a people,” which would often be quoted in the manifestos of future radicals.

Whatever the reason for its existence, Rhineland as of the late 1820s was a rising star within Europe. This was not so much seen as a threat to the power of the Concert of Europe, but as a threat to the power of the other members of the Republican Coalition. There had been several nations to join the United States and France as powerful members of the Republican Coalition. Mexico and Rio de la Plata were some of the most important powers in republicanism. Strong republics besides France in itself Europe were nothing new either. Ireland was a very influential nation on the Republican Coalition and the concept of the republic in general and Italy was militarily quite powerful. The difference with Rhineland was the fact that it was a very conservative state, had goals outside of the overarching desires of the Republican Coalition, and wished to stand alone.

The Rhineland Republic was being presided over by President Joseph von Radowitz, a Hoche-affiliated career soldier who had much respect and admiration for Hoche the general, but cared little for Hoche the politician or his principles. He loathed the Republican Coalition and their strict course of action: “This coalition only exists to further the goals of the French, the Americans, and their Latin friends.” Liberation had been a major goal of the coalition as of late, but the goals were very strict. No nation was to take new territory and only those who were considered politically distinct enough would become their own new country. Radowitz’s representatives were always sidelined whenever they brought up the idea of liberating the rest of the German peoples, with the fear being that they would simply be added to the territorial strength of Rhineland. Poland, Serbia, Hungary, Greece, Sardinia, and Catalonia were the only ones that were ever on the table, despite the constant setbacks in their liberation. It really seems as though the only options that were ever taken seriously were those proposed by the United States or France.

By 1827, Rhineland had enough of all of this and began to use the only card it had to pull against the other member nations: it threatened to leave the Republican Coalition. This did a little more than scare France, who saw a Rhineland that was not in the coalition as bad as a unified Germany in the Concert of Europe. For the sake of appeasement, a half-hearted plan began to be drawn up to begin revolts in Prussia and Austria. This only worked for a time, as Radowitz and the Rhinelanders saw no progress coming about at all. They did not decide to openly leave the coalition at that moment, but they did begin to act independently of it. Raids began to take place on the Prusso-Rhinelandic border to test the waters in an invasion of Prussia. These actions were quietly condemned by Hoche and the rest of the coalition, who contacted Radowitz directly to ask what was going on.

Radowitz responded that since the coalition did not pursue Rhineland’s interests and goals, Rhineland would have to pursue them on their own. Despite the smears of them for this, it was not as if Rhineland opposed the liberation of other nations in Europe. Radowitz himself was of Serbian and Hungarian descent. In July of 1828, the Rhineland Republic cut all ties with the Republican Coalition and began to recruit and train tens of thousands of more soldiers, placed along their eastern and western borders. Nobody at that moment was really sure what would happen next. Many in France and Ireland believed that Radowitz would declare himself king then and there, as if that were the goal. What nobody really expected was how this would affect the United States and its perception of the Republican Coalition and international politics.

The Rhineland Republic is one of the most important states to emerge during this period in world history. Based out of Stuttgart, it was originally only a small sister republic to France during the Coalition Wars, also called the Great European Wars. When Hoche took over, he more or less ended the exploitation of the sister republics by France, giving them the resources needed to govern in their own right. Many say he went to far with the German territories, as he allowed the disparate republics to unify behind one single government. He justified this move, which is almost universally viewed as the biggest political blunder of his career, with this famous statement: “Every culture, every distinct group of people has the right and duty to form a government to governor themselves as a people,” which would often be quoted in the manifestos of future radicals.

Whatever the reason for its existence, Rhineland as of the late 1820s was a rising star within Europe. This was not so much seen as a threat to the power of the Concert of Europe, but as a threat to the power of the other members of the Republican Coalition. There had been several nations to join the United States and France as powerful members of the Republican Coalition. Mexico and Rio de la Plata were some of the most important powers in republicanism. Strong republics besides France in itself Europe were nothing new either. Ireland was a very influential nation on the Republican Coalition and the concept of the republic in general and Italy was militarily quite powerful. The difference with Rhineland was the fact that it was a very conservative state, had goals outside of the overarching desires of the Republican Coalition, and wished to stand alone.

The Rhineland Republic was being presided over by President Joseph von Radowitz, a Hoche-affiliated career soldier who had much respect and admiration for Hoche the general, but cared little for Hoche the politician or his principles. He loathed the Republican Coalition and their strict course of action: “This coalition only exists to further the goals of the French, the Americans, and their Latin friends.” Liberation had been a major goal of the coalition as of late, but the goals were very strict. No nation was to take new territory and only those who were considered politically distinct enough would become their own new country. Radowitz’s representatives were always sidelined whenever they brought up the idea of liberating the rest of the German peoples, with the fear being that they would simply be added to the territorial strength of Rhineland. Poland, Serbia, Hungary, Greece, Sardinia, and Catalonia were the only ones that were ever on the table, despite the constant setbacks in their liberation. It really seems as though the only options that were ever taken seriously were those proposed by the United States or France.