Part 1: Bridge Over Troubled Water

"The principal weapon of the Corsicans was their courage. This courage was so great that in one of these battles, near a river named Golo, they made a rampart of their dead in order to have the time to reload behind them before making a necessary retreat; their wounded were mixed among the dead to strengthen the rampart. Bravery is found everywhere, but such actions aren't seen except among free people."

-Voltaire, 1775

Excerpt from: Chapter Four of A History and Guide to the Island of Corsica, by Napoleone Charles Buonaparte, 1883.

[...] It was thus that the Comte de Vaux's campaign came to a mountain pass known locally as the Bocca di Bigornu, and to the French as the Col de Bigorno. In the interests of obtaining a speedy and thorough defeat of the Corsicans, the Comte had decided upon a strategy of seizing Corte and controlling the very centre of de Paoli's strength.

The strategy, while perfectly sound in the tactical sense, was also decided upon with few alternatives. Indeed, while better supplied than the first French expedition to the island, the Comte de Vaux was operating under less than ideal circumstances. Advised to project French power into the Mediterranean, the King would purchase Corsica from the Genoese; advised to conserve resources due to the state of French finances after the Seven Years War, the King would send only what was thought necessary. Further compounding the Comte's difficulties was the state of the French navy, still in tatters after defeat only a few years prior. He had little naval support in his expedition.

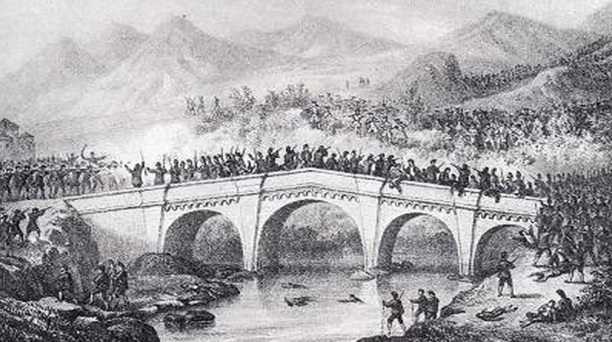

Thus, a land campaign, thrusting from what areas the French controlled towards the centre of the rebellion, was essentially the only option. de Paoli was aware of this, and it was quickly decided that the bridge at Porte Novu would be the strongest strategic point from which the French could be repulsed. Knowing that the Comte's strategy would rely on numerical superiority, de Paoli decided to meet the French ahead of the bridge proper. By sending two contingents of his forces forward, de Paoli sought to avoid a build up at the bridge itself.

Wisely, de Paoli assigned a sizable contingent of his finest and most trustworthy troops to hold the bridge itself, reinforced with local militia forces. In order to diminish the numerical superiority of the French, de Paoli had managed to purchase the services of a large group of Prussian mercenaries, once assigned by the Genoese to assist in retaking the island. The Prussians, under the direction of Gentili, were to assist in the initial forward actions of the Corsicans. [1]

For their services, although many would die, the Prussians would be paid handsomely from the national coffers. The Corsicans and the mercenaries met the forces of the Comte ahead of the bridge, and managed to hold favorable high ground above the road for some time. The advancing French were greatly unsettled, but soon managed to force their way forward, and push Gentili and his men into a retreat towards the bridge.

Need I say more of the gallantry and bravery of those men, heroes all, who held that bridge in the face of overwhelming strength? Of the men who continued to fight, even after death, as part of the rampart of corpses from which the Corsicans fired? It was as the blood lept from each slain man, boiling hot, and scalded a dozen Frenchmen apiece! [...]

The Battle at Porte Novu

The success of the de Paoli at Ponte Novu would shock Paris and electrify London. The Grafton ministry was generally slow to consider the public mood towards Corsica, despite near Universal sentiments in favor of the nascent Republic as a result of the fervent campaigns of James Boswell. Lord Shelburne would open a British consulate on the island as a gesture towards the Corsicans, but his and Grafton's concerns remained generally focused on the American Colonies. Half-hearted attempts had been made to bring together a coalition of Spain and Sardinia to oppose French expansionism, but nothing had come of it.

Yet the victory at Porte Novu made the Corsican situation impossible to ignore. Whereas before the Corsicans were considered plucky underdogs, now they were considered plucky underdogs with a fighting chance at victory, deserving of more support. Boswell declared that the "moral duty of Britain is to assist a brave people in their defense against tyranny." Even arch-Tories, skeptical of the highly liberal Corsican constitution, came to regard the Corsicans with grudging respect (though their attitudes were no doubt coloured by a preference for containing the French).

Lord Shelburne was thus put in a quandary. Concluding an alliance with Corsica would risk war with France, if they pressed their claims. On the other hand, refusing to further aid the Corsicans would likely topple the Grafton Ministry. While the British Empire maintained absolute naval supremacy over France, Britain's finances after the Seven Years War were hardly better than France's.

However, hardly better was still better, and the French coffers remained in a dismal state. Further, while a single military disaster at Borgo was excusable, a second military disaster (one featuring a French force with vast numerical superiority to the Corsicans) brought the entire mission into question. Could France throw an endless supply of soldiers at the tiny island whose determination seemed so resolute?

William Petty, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne (Lord Shelburne), after Sir Joshua Reynolds

oil on canvas, late 18th century, based on a work of 1766

Lord Shelburne, with Grafton's approval, therefore made the calculated decision to back the Corsicans more openly. The sabres at Gibraltar would be appropriately rattled, and a shipment of military supplies would be prepared to be sent. Implicit in this guarantee was that the ship delivering that precious cargo to the island would be well-guarded by the British fleet. Paris was appropriately outraged, but to its great concern the move was well received in Turin as well as in Madrid - the victory at Ponte Novu had been well regarded in Spain and Sardinia as well, helping to overcome their hesitancy to align themselves with the isolated British.

Lord Shelburne's next move is rightly regarded as a stellar diplomatic maneuver. He recognized the advantages he possessed, while also recognizing that Paris would likely be unwilling to wholly exit Corsica without some means of saving face. A deal was thus struck, and like so many good compromises, it left everyone slightly dissatisfied: Genoa's debts, which had been the original impetus to pass Corsica on to France, would be assumed by Corsica. France would evacuate the island, having obtained what it was owed. Corsica would thus enter Europe as an independent state - one heavily in debt, but independent nonetheless. Shelburne additionally made it clear to de Paoli that the forthcoming alliance between Britain and Corsica would include some assistance on Britain's part in regard to the debts, and the British public would soon find it in their hearts to send along much-needed money to the Corsicans.

The move was widely hailed in London circles, and gave the ailing Grafton ministry a boost of confidence it desperately needed. However, Grafton still found himself dealing with immense dissatisfaction from within his own government due to his conciliatory attitude towards the Colonies. From the other side of the aisle, the so-called "Junius Letters" continued to have an immense impact on the ministry's popularity; the success in Corsica would prove only a temporary reprieve.

Excerpt from: “An Examination of Buonaparte’s ‘A History and Guide,’” The Contemporary Review, Volume 23, by A. Strahan, 1889

Buonaparte, while spirited and perhaps even compelling in the retelling of the history of his country, speaks with great bias. Ultimately, the value of the work is most evidently it’s guide to the most beautiful and notable locales of that fair isle, if an adventurer is so inclined to venture there. [....]

Notes

[1]: This is the Point of Divergence for the timeline. In reality, Gentili and the Prussians were put in charge of guarding the bridge; for unclear reasons, the Prussians would fire the Corsicans as they retreated from the advancing French, and much of the army would be slaughtered in the crossfire.

Postscript I: An Introduction

Hello, friends.

Welcome to the timeline. This is a bit of a terrifying endeavor for me, the culmination of a great deal of brainstorming, writing, and something close to soul-searching. Much of my work in the AH space has been on maps and wikiboxes; this timeline got its start as a graphics TL over in the maps & graphics forum. I pretty quickly realized that creating a cohesive and believable world to set graphics in, at least from my perspective, required a thorough understanding of how the world got that way. From there it was a pretty natural move to begin work on a timeline proper.

The timeline has a single point of divergence, noted above. The impacts, however, will be quite significant. Napoleon is one of those incredibly crucial individuals of history, who seem to rise above the trends and economics and culture of it all and almost make great man history seem plausable. With this POD I'd like to examine a world without him playing the central role he did. I'll do my best to keep it plausible, though if you have questions or concerns or suggestions I'll gladly accept them. I can only store so much knowledge in my brain, so please let me know of your ideas.

My general notion for this timeline is for the POD to be like a rock dropped in a still lake. The first ripples will be quite small, and history will seemingly hew quite close to what we know. However, as things march on, the ripples will grow, and overlap, and produce all kinds of strange changes. I have some things in mind, but I'm sure other changes will develop naturally. This is as much an adventure for me as I hope it'll be for you all.

Much inspiration came from Milites’s To be a Fox and a Lion, from Planet of Hats’s Moonlight in a Jar, and from CosmicAsh’s These Fair Shores. Please check these timelines out, they're stellar, and I wouldn't be pursuing this if I didn't have such fantastic inspirations to aspire towards.

Thanks for reading!

-assouf

Last edited: