Chapter Eleven: The Battle of Mount Pangaios (July - October 270 BCE).

By July 270 BCE, Antiochus was in Byzantium. Antigonus had fled for Demetrias with the remains of his forces and his royal bodyguard. Pyrrhus was in Amphipolis. The arrival of Antiochus in Byzantium had been something of a cause for celebration. His partisans in Greece had eagerly awaited his approach and either rushed to meet the Seleucid king, assuring him of their continued loyalty, or remained wherever they had taken cover in Greece during the Antigonid period. The city of Byzantium had no issues letting him in (after all, he was the nearest major army in the field and Pyrrhus didn't have a particularly stellar reputation by this point). With Antigonus out of the way, Antiochus' crossing proved rather smooth. With him came the now-largest army in Greece or Macedonia. In the last few years of campaigning, the army had dwindled somewhat but Antiochus had made sure to raise some more soldiers, probably shortly after the beginning of the siege of Pergamon.

The Seleucid army in July 270 BCE numbered some 35-40,000 soldiers. As per usual, the core of the army was the Macedonian phalanx, made up of both Macedonians and Greeks. At the core of this was a contingent of, by now, very veteran soldiers. One source claims that, sometime in 275/4 , he had re-instituted the 'Hypaspists', the elite infantry unit headed by his father under Alexander III. Into this, he had folded many of the veterans of Seleucus' campaigns as well as many of his own veterans. Upon his crossing into Thrace, one historian places their number at maybe 6000 infantrymen. In total, the phalanx probably numbered 16-20,000. Alongside this was a skirmisher force comprising largely of Persians and Cretans, as per usual, but soon bolstered by Greek and Thracian peltasts. Then there was the cavalry. Persian cavalry was preferred and so too were the Greco-Macedonian 'companions'. However, for the first time, Antiochus actually fielded some 400 Gallic cavalrymen, largely to be used as scouts or raiding forces as per need. Finally there came the elephants. No Seleucid king would go to war without war elephants, numbered at 50.

Pyrrhus' army is more complicated. His initial invasion of Macedonia four years earlier was reasonably small, possibly approaching only 20,000. However, over time he had taken pains to increase his military force. Exactly what numbers he had in 270 are very much uncertain but estimates place it at a maximum of 32,000, mostly Greco-Macedonian infantry but with Gallic and Illyrian mercenaries, Agrianians, Thracians, and a reasonable contingent of Thessalian cavalry. Elephants too, of course though probably only 10-15 maximum (and possibly fewer). All of this placed him at a distinct advantage but it was far from enough to necessarily throw the entire war in Antiochus' favour. If anything, the months that followed would prove that rather dramatically. News of Antiochus' arrival would have reached Pyrrhus rather early on. However, while he knew of the king's arrival, he seems not to have worried all that much about it. On the contrary, he instead focussed mostly on bringing food into Amphipolis and repairing any breaches in the walls. Antiochus could cross into Macedonia without going through Amphipolis, but it would require him to take longer routes through Thrace and Upper Macedonia which might leave Byzantium undefended.

Similarly, he also diverted resources towards ensuring the defence of Eion closer to the sea, another crucial crossing-point along the Strymon which Pyrrhus hoped to hold against the Seleucid king. Pyrrhus didn't plan on letting this come to a siege but he also knew that the fortified locations of both Amphipolis and Eion gave him a crucial military advantage; Antiochus mostly

had to come through this way and so, as long as Pyrrhus held them, he could have a strong defensive location to fall back to should he need it. With that said, he clearly had no intention of actually needing to use the city defences whatsoever. On 17th August, as Antiochus began his march on Amphipolis, Pyrrhus sent ahead a set of ambassadors informing Antiochus that he had no intention to fight and that he would be willing to surrender Thrace to the Seleucid king and recognise Amphipolis as an inviolable boundary between the two. Antiochus refused.

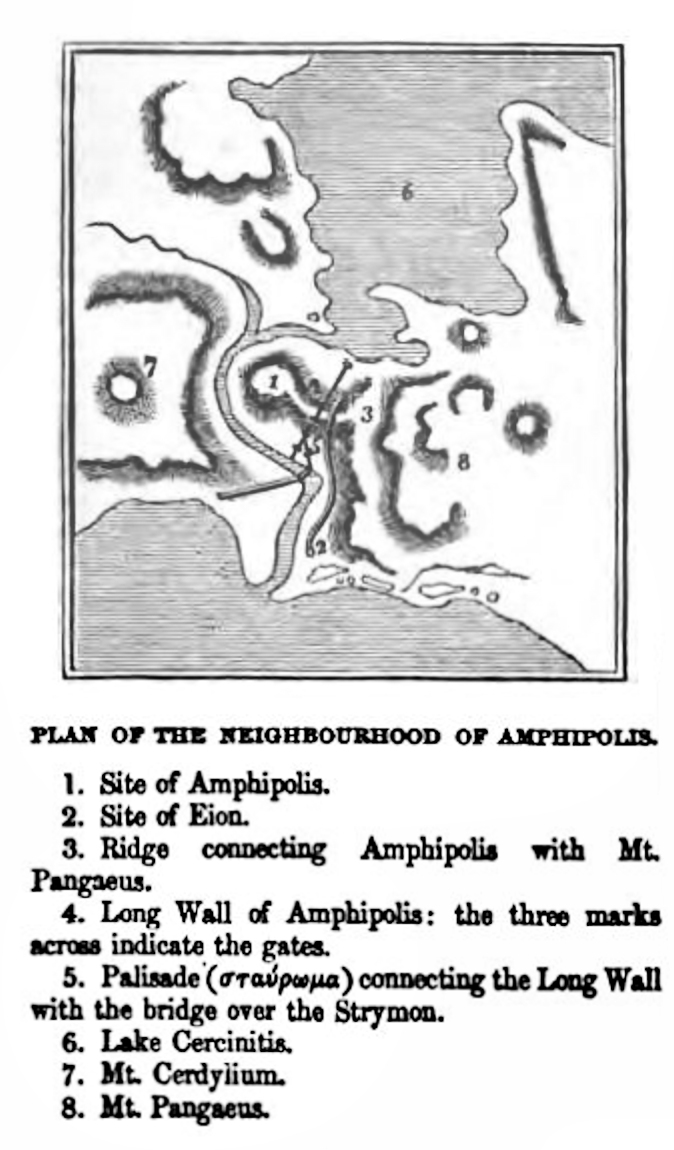

Probably between the 25th and 30th of August, Antiochus arrived at, and took control of, the city of Philippi on the other side of the Pangaion hills from Amphipolis. Here was the trouble. To the North of Amphipolis and Eion was Lake Cercinitis, to the South was the Aegean, to the West was the Strymon River and, to the east, the Pangaion hills and Mount Pangaios itself. Amphipolis sat on a ridge at the base of Mount Pangaios, protecting one route around the Southern bank of Lake Cercinitis. Eion protected the route around the Southern side of Mount Pangaios and along the sea. Crossing the Strymon required taking one or the other, but it also required Antiochus to march his army through at least two very narrow chokepoints. It also put him in the position of having to deal with some very rough terrain.

Sure enough, in early September, the Seleucid army made its first attempt to approach, apparently angling for Eion from which it could cut off Amphipolis, a rather harder siege, from any support from the west. The result was an absolute catastrophe. As the Seleucid army marched, the rough terrain of the Pangaion hills made formations difficult to maintain, the Seleucid columns got broken up and, while their war elephants had very little trouble, the heavy Seleucid infantry found the march rather more difficult. For Pyrrhus, the hills offered his slew of lighter infantry and skirmishers a very real opportunity. Sure Antiochus had plenty of the same, but his army had spent the last while largely fighting in traditional Hellenistic battles, not against an army ready for warfare in the hills.

On the morning of the 8th September, Antiochus' scouts informed him that Pyrrhus' phalanx was approaching from the east. Antiochus marched to give battle, both armies meeting the next day. On the first day, Antiochus offered battle but was refused. On the second, he offered battle once again and was refused a second time. Only on the third day did Pyrrhus finally prepare for battle. At first, the fighting seemed rather skewed in Antiochus' favour; Pyrrhus' skirmishers fell back before the assault of the Seleucid archers and the Seleucid cavalry was able to drive Pyrrhus' Thessalians into a retreat although were prevented from giving chase by the Epirote elephants. Both phalanxes had difficulty manoeuvring and keeping formation on the rough terrain so, for the time being, the battle remained largely in the hands of the various skirmishers. It is said that, during these first few hours, the Gallic cavalry also distinguished itself on several occasions for their bravery, darting in to harass Pyrrhus' lines before escaping any retribution.

Just when Antiochus might have felt the battle going his way, however, the trap closed. Pyrrhus had spent the last two nights getting his army into place, sending some 4000 light infantry around longer paths to take up a position

behind the Seleucid lines. Now, with the Seleucid army largely committed, the Epirote skirmishers swung into the fight with as much noise and fervour as they could muster. Descending upon Antiochus' army, they began harassing the rear of his infantry lines causing significant disruption and breaking the Seleucid infantry, allowing Pyrrhus to lead a cavalry charge into the gap which began breaking the Seleucid morale. His cavalry, returning from their bout with the Persians, once again engaged their Seleucid foes in an attempt to keep Antiochus from leveraging his greater cavalry forces to cover their retreat while Pyrrhus' infantry surged forward, largely abandoning their pikes in favour of their short-swords which would now give them much better flexibility in the hills.

The Seleucid infantry began to rout. At this stage, Antiochus had probably his most ingenious idea. Leading from atop a war elephant, he brought his own elephants (until now placed on the flanks in an attempt to check Pyrrhus' cavalry) around just ahead of his infantry. There is an important point to be noted about elephant warfare. Elephants weren't actually

that good in battle. For all that is made of their weight and size, these attributes were most often countered by their tendency to panic and flee as well as the fact that horses could easily outspeed them. A commander who knew what he was doing, like Pyrrhus, could even use javelins or other skirmishers to annoy, or kill, elephants. Typically elephants didn't march unsupported; they usually had warriors on their back (sometimes in small towers) as well as small groups of soldiers by their side to help protect against skirmishers.

What elephants

were good at was a variety psychological and tactical factors. People, and horses, were often scared of elephants so they could drive an enemy to rout on occasion and were often very good at providing a check against enemy cavalry forces, at least those not used to fighting with elephants. In this instance, both cavalry forces seem to have been plenty experienced; Antiochus' Persian cavalry had been turned back by Pyrrhus' elephants but largely because of the support of his own Thessalian cavalrymen and the skirmishers on the back of those elephants. Antiochus had probably placed his elephants on the flanks intending to use them in the same way both he and Seleucus had done against the Gauls, keeping one flank safe against cavalry and giving him an extra field of manoeuvre over his enemy, or as a final charge to help break a routing foe.

The other advantage to elephants was that they provided very helpful command towers. From atop an elephant, Antiochus could both see the battlefield and be seen by his soldiers. Now seeing his forces begin to rout, he swung his elephants ahead of the infantry lines to provide a temporary relief from the advance of Pyrrhus' infantry. Alone, the elephants wouldn't hold but, for now, the arrival of his elephants provided another barrier between Pyrrhus and his infantry and, just as importantly, between Pyrrhus' infantry and his flanking forces. Fearing that Antiochus' elephants were about to cut off his retreat, Pyrrhus swung around to reunite with his forces to prepare a larger assault which might finish off the Seleucid army.

However, the retreat of Pyrrhus' cavalry gave the Seleucids vital time; seeing their king at the head of the army and encouraged by the

hypaspists who had still held their ground, the Seleucid infantry was able to begin rallying and, along with Antiochus' skirmishers, drive off the Epirote flanking force with the Gallic cavalrymen giving chase to ensure they wouldn't simply reform and return to the fight. Still, Antiochus had suffered heavy casualties and had no guarantee that his elephants were about to swing the battle in his favour, especially now that his movement of the elephants away from his flank had freed up Pyrrhus and is bodyguard as well as forcing the Seleucid Persian cavalry to compete both with Pyrrhus' Thessalians and deal with the Epirote elephants (although his companions, on the other flank, remained equally matched against their enemies, even driving the Thessalians back). The biggest problem was Pyrrhus' skirmishers; Antiochus' archers seem to have taken heavy casualties (due to their being

behind the Seleucid line when Pyrrhus' flanking force arrived), leaving him with less ability to actually counter the raids of Pyrrhus' infantry. Not to mention, the placement of his elephants ahead of the Seleucid infantry posed the very real threat that, should they flee, his infantry lines would be shattered, allowing Pyrrhus to carry the day and slaughter his army.

Instead, he fell back. Here, on the Pangaion Hills, his army stood no chance. What he still had was a reasonably intact cavalry force (Persians on one flank and Companions on the other) and an infantry contingent that could still fight. Here, Antiochus was playing with fire; Pyrrhus had prepared for this encounter, his army was more flexible than Antiochus' phalanx, his skirmishers more numerous and effective, and his cavalry (although possibly outnumbering Pyrrhus') was not in a position to actually outflank anything. While Pyrrhus prepared his infantry, Antiochus gave orders for his own infantry to begin a fighting retreat, less veteran infantry first. At the rear came his

hypaspists. Finally, the skirmishers and elephants pulled back together; the skirmishers screened the elephants against Pyrrhus' own javelins while the elephants formed a wall to help protect the retreating infantry. His cavalry rode alongside, pushing back several attempts by Pyrrhus' own cavalry to harass the Seleucid lines and ensuring that the majority got away.

The Battle of Mount Pangaios has often been seen as a stalemate but, if it was a stalemate, it was a costly one. Pyrrhus had largely carried the day; most of his army was intact and he had dealt Antiochus a very bloody nose. While the Seleucid army had retreated, they had lost a significant number of infantrymen, at least some cavalry and had certainly lost a fair amount of prestige. Retreating to Philippi, Antiochus began bracing for a potential counter-attack but none came. Pyrrhus had also learned lessons from the battle; Antiochus' army had plenty of veterans (just as his did) and any fight fought on Antiochus' terms was bound to be a bloodbath. Pyrrhus was almost certainly a better commander than Antiochus but that didn't mean that his rival was weak and he certainly still had plenty of extra elephants and cavalrymen who, in a regular battle, could very easily swing the engagement in his own favour. The battle had been won but the war was just beginning.

Significance:

The Battle of Mount Pangaios is an interesting one which has drawn a lot of comment by a lot of different scholars over the years. The first point to note is the tactics. Pyrrhus had completely abandoned the pike phalanx in favour of short-swords, a lesson apparently learned from his run-ins with the Romans. In the rough terrain, the phalanx often got broken up which could provide opportunities to shatter the formation entirely. The cavalry charge against the infantry front was bold but taken straight from Alexander's playbook. Instead, Pyrrhus had opted to focus on the short-swords, betting on the ability of his infantry to adjust and the disunity of the Seleucid phalanx to provide an opening into which he could pour. This was a battle built on flexibility and manoeuvrability, a battle which focussed more on skirmishers and lighter, more flexible infantry than the pike phalanx.

Such tactics were not new in Greece. Indeed, Aetolian warfare had used flexible infantry and skirmisher-based armies for centuries, as had Cretan warfare. Isocrates, the Athenian general, had made good use of skirmishers in several campaigns in the 4th Century. It is important to remember that the pike phalanx was far from the only tactic used in Greek warfare at the time. What is often significant for people, however, is that Mount Pangaion set the tone for much of the rest of the war. Antiochus too learned from his lessons. When he next attempted to cross the Pangaion Hills, several months later, he did so with a much larger force of skirmishers. In March 269 BCE, Antiochus once again entered the Pangaion Hills after having spent time travelling in Thrace. With his army came a large contingent of Thracian skirmishers.