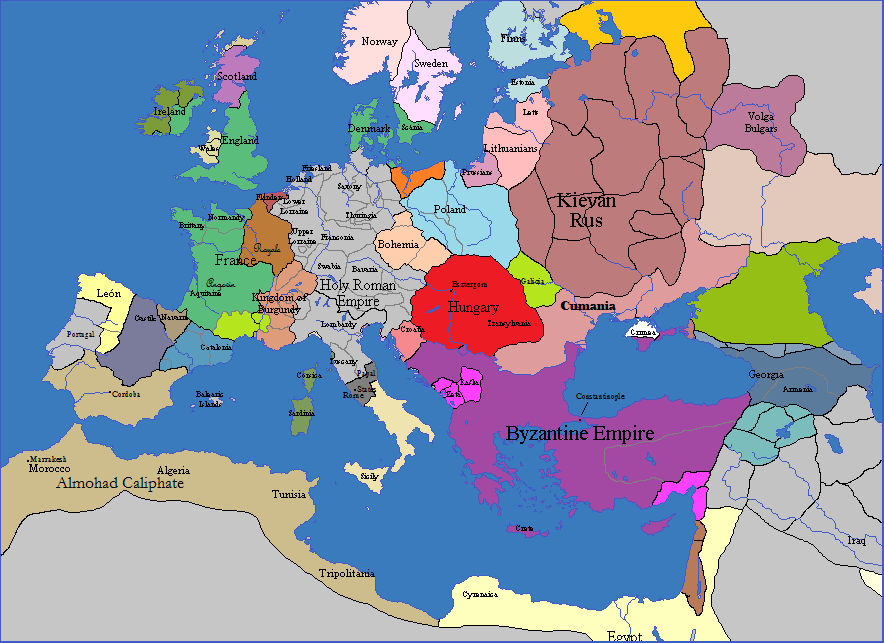

And, with many apologies for the delay, here is the 1178 map. It will go much faster now that this one is done, and that I'm moved into my new home. Please comment and critique, I'm happy to make edits. It's based partially on the 1135 and 1200 maps, and about 15 other maps of the 12th century and some written sources.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Turul on the Bosporus

- Thread starter mitfrc

- Start date

1178

Constantinople

Maria watched her husband’s coronation with the eyes of an eagle, scanning from threat to threat. It was a joyous day, the blessing of the Patriarch, the parades, the races in the Hippodrome and the jousts too. Enthroned at his side as co-ruler with her father, she had reached a pinnacle to all her aspirations. But in the audience she could mark out the threats:

There was the Protosebastos, and there was Andronikos Komnenos. There was Andronikos Angelos, and his young sons; and there was the youthful but old enough to be respected Alexios Doukas whose countenance well befit what Maria imagined Cassius might have. To some measure the better part of them were related to her; none of them were necessarily happy about Béla and all were threats to her children.

Each and every one of them might materialize into a threat. Her husband, her Alexios, would be the personification of the Empire, the Shadow of God on Earth, to the people; and a hammer on the frontiers. She... Would make sure that nothing touched her children. The Purple was the right of her family, and so it would remain.

Her serious countenance was appreciated by all during the ceremony, but expressed nothing. Without moving her eyes to admit the weakness during the high court ceremony, she still observed the expressions and countenances of every one of them. There were risks about, conspiracy in the air. While her father lived they might fear too greatly to conspire, but it would change. It always did.

1179

Esztergom

The Matter of Hungary had necessarily needed to be settled. Béla, to rule both Kingdoms, needed a steady and reliable hand on the tiller. To this he arranged the marriage of his sister Helen to Baldwin of Antioch, the son of Constance of Antioch and the Knight Raynald of Chatillon. The young man, only twenty-four years of age at Myriokephalon, had nonetheless been one of the ablest of Manuel’s commanders and had become a true bosom friend of Béla’s, a pure knight, but competent enough to restrain himself when needed, and much favoured by the old Emperor.

Béla had felt someone with a western connection was needed; he could not see one of the old Byzantine nobility doing anything other than causing dissensions in the Hungarian church. But Raynald was also a man of merely knightly origins and so to even marry the sister of a King was a great privilege for his son; by his countenance and by his station Béla did not fear him, especially that he was foreign to Hungary, and so, in a mirror of the position that he and his wife were to hold as Co-Sovereigns of both Rome and Hungary, he made his sister and her husband Baldwin Co-Viceroys of Hungary.

Béla had traveled to Esztergom with the return of the Royal Army’s expedition to support Byzantium, many contingents having remained campaigning in Anatolia for the past years, and others having seen many of the Knights and younger sons of Lords disperse to settle the good horse-land of central Anatolia. Anatolia was still a problem; the nature of the land had changed, with the central plateaus being reserved for horses. It was good land for the Hungarian settlers, but it had no ready Imperial administration; a few cities like Iconium had been reasonably prosperous under the Turks and it were now remitting taxes to Constantinople, but the rural expanses of the plateau itself would need years to recover and when they did, it would be as pronoia for Lords who found themselves with great cavalry grazing land. The tradition of being open plains horsemen was largely dead in Hungary, but the men who settled there would have to rediscover it. The old systems of agriculture had been lost to the Turkish administration, and by necessity the only way to bring it back under control was turn the whole of the highlands into a series of pronoia grants.

Returning to Hungary with the rest of the Royal Army, however, he did have reinforcements. Turks. A certain number of them had chosen to convert to Christianity when presented with the ruination of their state, and were allowed to summon their families and join Béla’s return home under arms. He had a plan for them, and it was a plan that he had executed on his return.

With a small Byzantine contingent to represent his authority in Constantinople and provide specialist engineering skills, he had crossed the Danube into the trans-Olt region and swept through the petty chiefdoms of the Cumans and the Vlach lords which represented the extreme end of Cumania. With little opposition he had established a series of posts along the Olt river and proclaimed the region the Banate of Severin within the Kingdom of Hungary. It was here that he settled the Turkic converts as well as some Cumans who chose to acknowledge his authority. Then at the end of the 1179 campaigning season he had carried on to Esztergom to witness the marriage of his sister and Baldwin and solemnize their position as Viceroys of Hungary.

The campaign had been almost desultory, since the trans-Olt was far from the centres of Cuman power and most of the land was in the power of petty Vlach Lords anyway. Without any significant battles, the power of being squeezed like a vice between the Roman lands and the Hungarian lands had made it a trivial exercise in the power of the new alliance to compel the submission of the local magnates, supply land to the settlers in a territory almost denuded of population, and then carry on through Transylvania and on to Esztergom.

The advance to Ersztergom was hardly a regular, shortest-distance course. Instead it became the character of a Royal Progress of the returning King and Army from victory against the infidel, visiting the towns and cities of the Realm of Hungary and receiving the homage of the people, from the Transylvanian mountains to the rolling Pannonian plain about the Danube. This was the land of his birth, and Béla took the necessary opportunity to hold a roving court, dispensing justice and hearing the complaints of the people.

Now, in Ersztergom in the fall, the brave young General of the Roman Army, but a Latin born of the Holy Land, was wed to his sister, and Béla raised his sceptre to proclaim them co-Viceroys for as long as he pleased of his Crownlands of Hungary, commending the diet to hear their laws passed in his name and obey their decrees. In the realm of his forefathers, used to traveling Kings, with his brother defeated, his Royal authority was sufficient to secure by acclaimation the arrangement, which provided a mirror of his own position of authority in Rome.

1180

Constantinople

When they found him dead, his courtiers and servants all agreed the expression on his face had been peaceful. He had died in the night, with his wife calling for the servants when she realised he was still.

Maria and Béla had come a short while later. Maria closed her eyes and stood beside her father, as the priests and deacons congregated, she followed along to the prayers of the dead. But there was something light in his countenance, it was true. For his entire life, the future of the Empire had been uncertain, the patrimony of Rome, the Empire that was a reflection upon Christ in Heaven.

Then, four years before, in the swirling dust of Manzikert, they had overcome the Turk, and marched on to Iconium and reclaimed it for the Empire. Now the border was what it was in the distant time of the Isaurians, or better. He had died in a measure of triumph, with the Empire at peace and the borders, thanks to her marriage, more secure than they had ever been. It was a Good Ending.

The Priests might have felt a less about it, though. Perhaps it was only Maria’s imagination but the dispute over the anathematization had been particularly bad, and that one was important because it touched on the matter of converts from the Turkish-occupied land, particularly the large number of Turks who had been willing to convert, and settle under Béla in the Banat of Severin. The Emperor’s preferences had prevailed, but Maria couldn’t help but feel that it was a bit of bad blood late in her father’s life that had been unnecessary to the political circumstances.

The procession ended in the Hagia Sophia, on an Autumn day with the Golden Horn and the Bosporus reflected in light. The censers filled the air with incense, smoky in the great church, entering the Imperial Gate one more time, her father was. This was the funeral of an Emperor; the chance to give an account of his life to God and to commend his soul to the mercies of Christ. But the Empire of Christ continued, and even here, even at her father’s funeral, she had to be prepared and ready for the conspiracies that might come.

At Maria’s influence the Parakoimomenos was a eunuch again and she had cause for that; as a woman of the palace she connected better with the eunuchs of the administration and had no disrepute for being in their presence long enough to properly plan, and they, without families of their own (especially the ones of foreign birth, as Tabakorios was), could be induced to support her for the interests of the Empire and the improvements of their comforts in this world and, if faithful, gains to the Church for the sake of the next.

Tabakorios, head lowered, allowed a subtlest of nods. The servants were in place who would secure the Hagia Sophia. Maria did not expect her enemies to move immediately nor in so holy of a place, for it would turn the Church against them when they might otherwise count on it as an ally, but she was prepared anyway.

Her husband’s complicated situation with religion was one that bore some reflection. Hungary was Latin, and the Empire, of course, was the Empire, with the Patriarchs of the East behind its profession. The disputes were because of the Pope who desired the overweening power of being both Pontifex Maximus and secular Emperor, there was little else that could properly describe their actions. Béla was trapped into a delicate policy of avoiding alienating the church in Hungary and respecting the faith of the Empire.

Of course, Hungary had a large number of Orthodox subjects as well, and the Empire necessarily maintained some Catholic churches for the benefit of the otherwise wild Italian merchants. That course was the one that Béla would have to dance most carefully on his own. He knew the latin church as one raised in it.

A part of her quailed at how she spent her father’s funeral, almost nervously obsessed with the potential for trouble, with the strategy surrounding her reign with her husband. She should be celebrating her father’s life instead. But he put me here, in an act of trust, and it could all be undone in a single hour of conspiracy.

Maria intended to be ready for it.

And as to what Manuel Komnenos thought of that, now judged by God on account of his contrition before the Lord of his heart and soul, that was between him, and God, and all the Emperors in heaven who had gone before. The two Sovereigns, clad equally in the regalia of Roman Sovereigns, observed together side by side, as husband and wife, the entombment of he who had gone before, the man who had set in motion everything that would matter about their lives.

Night settled over the Golden Horn, of a city that had never been this prosperous before, a city in a world that was returning to the ways of commerce and civilisation that had not been reached since the height of the days of Rome. Now, husband and wife would have to keep it.

1181

Constantinople in Summer

Following a strategy of cautious moves, Béla had combined his Hungarian and European Roman Armies into a single force in 1181, meeting in the Banat of Severin, and crossed the Olt. The next five months had consisted of a careful and methodical campaign into Muntenia beyond the Olt. To say that there was any real organised Cuman resistance was to exagerrate the organisation of their confederacy and its extension into those lands greatly.

At a ford on the upper Milcov in August, he had presented his combined Army against Cuman chieftains trying to fight him, and turned them back. Though the struggle at the Milcov ford was hardly decisive, it had begun to establish a new, tidy frontier for the Empire, defined by the limits of Muntenia, which unlike Oltenia—the Banat of Severin—he prepared to place under a Roman governor, for the first time across the Danube in many centuries.

At home, Maria’s first concern had been over the Church and the Latins. In general with Italy having calmed the situation with the west risked trouble, because the King of the Germans had a free hand to consider action against them. So far, though, their allied city of Ancona had not been threatened, the bigger problem was with the Republic of Venice.

Her father had, concerned over their commercial power, turned against Venice, using the pretext of attacks on the Genovese settlements in Galata. She had seen in the growing rivalry a seed of danger, and reached out to the Venetians through the usual cut-outs, after an exchange of letters with her husband on campaign. She proposed allowing them to build a settlement further up the Golden Horn from Galata. This would restore parity with the Genovese, but would also be more restricted than their position because of the lack of direct frontage on the Bosporus.

The diplomatic effort was important in the context of potentially needing to defend Ancona against the German King, and it was more importantly necessary, as she saw it, to secure the conspirators against her husband from having foreign help. Her spies were already busy; from the Post to the eunuchs of the palace that she had won over. The question was how much good it would do.

Constantinople, as winter comes

In the night, breath on the air was starting to become faintly visible. It was still reasonably warm, though, the gentle climes combined with the general warmth that had lasted as long as the Komnenos had ruled, perhaps a blessing from God. Others said it had been the same during the reign of the Macedonians.

Constantinople was a city of plenty, if not peace. As the entrepot to Europe for trade with the east, and once again as the metropole of a great Empire in Anatolia, the wealth continued to flow. The hundreds of thousands who lived in The City could see themselves as the heirs in comfort as well as culture of ancient times, enriched by the redemptive power of the Church.

The winter might be mild, but the emotions were anything but. The eunuch’s name had been Sayf as a child, but was now Marcian and under heavy palace robes and cloak the beginnings of the night’s chill did little hurt. There was considerable danger in the affair, but for a eunuch quick-witted conversation was the best way out of it (though Marcian was certainly capable with a dagger, and carried one).

Much of the Empress’ effort came down to this moment. A single passed message in the night. The hour is late. It was not the time. The details would remain unread, so much the better for the long-term survival of those involved.

-----

The Empress Maria was awoken almost immediately when the letter reached her in the palace. By flickering flame she read the delivered message. Her eyes flicked over it once, and then again. “The Vardariotai are still with us, as I expected. Have them use only whips against any mob put into the street, but make sure they are under full arms. The detachment of the Varangians shall secure the palace. All of the servants will be searched for hidden weapons.”

“As you command, O Empress!”

Though fewer and fewer Magyars were actually in the Vardariotai, one of the reasons that her father had placed them as the primary palace guard was their Magyar identity; with Alexios as his heir, the shared bonds created an esprit de corps even if it wasn’t really true. The Vardariotai, in some sense, because associated with the Party of the Magyars simply because everyone expected them to be. But Maria had leaned on that and made sure that her husband cultivated it into a real relationship, and now they were critical.

The revolt took the character of religious protests the next day instigated over the anathemas from her father, demanding their renounciation, and also a generalised pushback against a perceived ‘Latinisation’ threat pointed at her husband. They were turning out the people of the city as the cover to move troops and execute a conspiracy.

Of course it would be done when Alexios wasn’t present. The hero of Myriokephalon was seen as too dangerous, the rule of women inherently weak. The troops could be paid to eliminate him when he tried to use the Army to retake his city.

In a way, the game was as predictable as it was deadly. It was a matter of perception, where the party which won was the party which looked like to everyone on both sides that it was going to win. If it seemed like you had momentum, then you rapidly actually had momentum.

That was why putting the Vardariotai onto the streets with the dawn was critical. Before the mobs could even form up, these soldiers on horseback were waiting for them with their whips in hand, in uniforms of red. The Vardariotai drove forward against the forming groups and lashed them with their whips. Horses rearing and prancing, they mock-charged again and again in small squadrons, driving back the mob, whipped up by picked monks, with a combination of intimidation, mass and the whip. The clattering of hooves on the paving-stones thundered through the canyons of the high, red-roofed buildings.

“Come on lads, faster now!” Another right wheel and the horses spinning in a broad square, forming up and reins slapping and cracking, whips trailing down right as they charged into another group trying to occupy the square. They spun around at the last moment, a few of the crowd knocked down by horses but not many, and the rest subjected to a good whipping across the face as the Vardariotai slowed and rode along the front of the group. Part of their number peeled off and circled the mob, whips rising and falling with almost rhythmic cracks.

One squadron forced a group of ringleaders away from the mob they had raised, and circled them, constricting them into a little knot as their whips flailed down on their heads and faces mercilessly. Behind them, the mob dispersed before it had formed, bereft of momentum and leadership alike.

The main point of the mob, beside demonstrating momentum, had been to conceal the movements of the conspirators and picked bodies of men through the streets. Without the mob in place this collapsed, and soon the Vardariotai had the opporunity to avail themselves of their swords, as armed bodies moving through the city in contravention of the proclaimation which Maria had had the palace officials read at dawn were set upon.

As they were, a column of Varangians left the palace, moving quickly to the residence of the Patriarch, and pushing aside any resistance or opposition encountered along the way. They secured the environs while messengers from the Empress, eunuchs and officers riding protected amidst them, dismounted and respectfully entered with a message.

By noon on the clock, the city had calmed. The Vardariotai’s officers had been used to remove several commanders of the city watches and then the troops had been turned out to secure the gates. The critical thing now was to prevent an escape of the conspirators. Boats were secured, merchants were searched, and all gates save one, heavily guarded, were closed. Anyone leaving by that gate was again searched. The searches ultimately revealed what the letter had indicated. Andronikos Doukas and Isaac Komnenos had been implicated in the conspiracy, and the interrogations revealed that their hiding place was in the Venetian quarter.

But this was precisely why Maria had reached out to the Venetians. The situation was good enough now that instead of having participated in the abortive Coup, the Venetians handed the conspirators over. Put to the question, they implicated Isaac Angelos with themselves merely as catspaws, and Maria promptly had them blinded after the interrogations were complete. The first challenge to their reign had been dealt with. But Isaac had fled, and trouble would remain afoot.

1182

Varna

After the attempted coup, Béla had hastened back to the capital. He had done so only to find Maria and their three children safe and Maria firmly in control. He had presided over the remaining trials and then spent the winter seeing to the administration, and taking reports, including the succession disputes continuing in the Emirate of Mosul and the progress of the great Sultan of Egypt in Syria.

Béla had resolved not to be consumed by the internal dissensions. Part of being respected as the Empire of Rome was projection. Maria had handled the plot, Isaac Angelos had fled to Italy. He had taken the necessary steps to be ready and to remedy the deficiencies in the administration. That was all that was needed at the moment. It was better to look authoritative, permanently settling the defensive position of his realms.

In light of that, with spring, the continued restive nature of Muntenia meant that a second season of campaigning was required across the Danube. Again, contingents of the Roman and Hungarian Armies had gone forth into the fertile lands north of the Danube. There were Cuman bands to fight and there were strongpoints to establish, old roads to repair and bridges to fix, in a land that had been indifferently civilised since the height of the reign of the Good Emperors.

This was a kind of thankless campaigning, for it brought no great victories or glories. It was, however, necessary to obtain the design of a defensible frontier with the East and the steppe, in the dense network of rivers that grew from the mouths of the Danube east of Muntenia. And so the Army went forth.

Now, though, he had returned to territory he held with surety, at Varna on the Euxine Sea, and there was good reason for it. The Emissaries of King George of Georgia had come to him to treat on matters of interest, and he was inclined to meet them.

Originally, he had envisioned Georgia as a tributary state of his Empire. But the reality was that the Georgians themselves had grown great in their time of freedom, and were oppressed on many sides by enemies they needed to fight at all costs. Now, however, he met with the Georgians as allies. The restoration of Anatolia had proved no quick panacea, for the nature of the land had changed, and the effort to resettle it with Christian Lords and horsemen and to restore the tributary native Christian population to prosperity, to christianize the Turks that remained, would take time. Time during which it was best to hold the border at the old line through the Taurus mountains.

In that vein, he had accepted Georgian efforts at negotiations. Though the circumstances were nothing like what they would be in Constantinople, that worked in his favour to a certain extent. Surrounded by strong contingents of troops and on campaign, Alexios presented a muscular image of a man and King and Basileus in the prime of his life, leading his Army in person, used to the rigours of the Field. A squadron of the fleet stood in the harbour when the Georgian emissaries arrived.

What they revealed was that there had been considerable dissension among the Muslim Lords of Syria, and that the Sultan of Egypt had led a massive Army north to Syria, and had recently arrived in Damascus. The Georgians themselves felt that they could master the petty Emirates as far as Lake Van if the Empire supported their flank, but that they would need to act quickly for they thought that the Sultan of Egypt intended to secure the submission of all Syria and perhaps many lands further to the north.

Alexios felt that the situation was profitable, though he had little interest in attempting to expand into Syria, which promised a heavy price to hold; his only concern was to support his vassal of Antioch, which was threatened by Saladin, though he could see, in the rugged mountains secured on the flank by Georgia, some opportunity for the restoration of minor cities and valleys to the south of Trebizond. And so he offered to put an Army in the field for the campaigning season of the next year, if the Georgians would so the same. He would not make haste from one theatre to another.

After some discussion and appeal, the Georgians assented to the firm intentions of the Emperor, and the audience was concluded. A few months later, Alexios received a message from King George, affirming and accepting the terms of the operation, to muster armies for a campaign in eastern Anatolia for the campaigning season of 1183. Alexios then sent letters to his vassals of Antioch and Armenia, directing them to prepare their troops the coming year.

1183

Charpete

High in Eastern Anatolia, in lands defined by the bend in the upper Euphrates, an Army was marching. Thirty thousand troops, this was no small force. Contingents from Hungary were there, and the Armenians. Antioch, beset by foes, had not yet been able to detach her forces as Alexios descended with the standards of Rome against the forces of Diyarbakir. The Artuqids had rushed troops to face them here at Charpete, but they were the Lords of three cities of the East.

The Empire had something of the character of the Empire again. The Armies of the Artuqids were not so great. Banners and pennons fluttering, the light horse of the allied and tributary Cuman bands and converted Turks descended first with the heavy lancers of the Empire following down toward the city. The Hungarian lance, both from Pannonia and Anatolia, under their respective banners, glimmered in armour under the sun of early summer. Approaching from the West Southwest the rising sun of morning was in their eyes; it was the only advantage that the Artuqids had, drawn up on the plain south of the city.

And then their ranks began to panic. Cries came from them, something they could see and the Romans could not. After thirty minutes, they began to abandon their positions and flee to the south, without coming to contact with the Roman host.

The forward scouts, about fifteen minutes later, came charging back up toward Alexios’ camp, and within an hour he knew, for they came bearing messages. “The Georgians, O Emperor! The Georgians! They have come by way of Acilisene from the North!” Having overthrown Erzerum, the Georgians had continued their advance through the northeast while the Roman Army worked its way east of the fortress line. Now, as planned, they converged.

Alexios grinned and flung a mailed fist skyward. “With the blessings of Christ, for Amida we march!”

Diyarbakir

Of course, Saladin had not ignored the advance of the Roman and Georgian Armies. He had abandoned the siege of Kerak and marched north, bringing a great host which grew in numbers as he elected to sign an armistice with the Emir of Mosul as both were threatened. Leaving Diyarbakir—Amida—to defend itself, the remaining field armies of the Artuqids had fallen back and pledged themselves in homage to Saladin in exchange for his assistance.

These two Armies were concentrating for a clash of arms of considerable size. Alexios had advanced first, placing Amida and its black walls under siege. At the same time that he had put up the lines of circumvallation, however, defensive lines of contravallation also went up, the Antiochans providing information that Saladin was marching north. The area was fertile and water was easily diverted from several streams into their siege lines.

There were almost forty-five thousand Roman, Georgian and tributary troops at Amida; Saladin came with an army, including all of his allies to face the threat, of more than thirty thousand. Though outnumbered, he advanced confidently from the south toward the black-walled city. The Armenian Lord Sargis Zakarian was the commander of the Georgian Army and he favoured remaining in the fortified works against Saladin. The aged General Kontostephanos was the only one of his father’s great commanders with him; he favoured standing out for battle.

“It is ill to risk the water diverted or being trapped in place by the armies of the Sultan of the Egypt,” he explained. “O Emperor, we must be prepared to fight on our terms, not those of the enemy. There is no natural terrain to support our lines and an assault from the walls of Amida at the wrong time would halve our strength against the true threat—but the garrison is not strong enough to greatly add to Saladin’s array of battle if we can choose the terrain on which we fight.”

“Lord Sargis, do you have an answer?”

“We have plenty of water and supplies for weeks within the lines, O Emperor,” he answered. “The enemy will not know our resources or those of the enemy. He will risk the fall of the city if he does not attack, in our favour. Recall Caesar’s greatest triumph.”

“Alesia,” Alexios ran the word over his tongue. The writings of Caesar were mandatory knowledge for a King and an Emperor, but the vision of Gaul hung as a dim story. It was, on the face of it, sound strategy. But the Black Walls of Amida were far different from the situation at Alesia. He briefly considered attempting to storm the city before Saladin arrived, but that seemed a wild proposition. He had been raised to prefer the attack, but practical education in the Imperial court had shown him a different side to war.

“We will hold position.”

-----

Within the first week, Alexios had realised it was a mistake. Lord Sargis’ advice had been sound, in principle, but the moral effect of Saladin on the battlefield had not been accounted for. Instead it was a matter of the great enthusiasm people held for him. Amida was resisting stoutly, encouraged by the knowledge that Saladin was outside the walls. Saladin, for his part, made no attack on the contravallations, and contented himself with using his cavalry aggressively and skillfully to prevent raids and to prevent any kind of foraging of the combined Roman-Georgian Army; he was in for the long haul.

The problem was not food for the Army, of which they had had plenty. It was forage. The horses would be weak and, unable to charge properly, ultimately any break-out attempt would founder on the hunger of the horses, and the Army, even if it escaped, would be stuck without wagons, again for the want of fodder, to carry its own supplies. It was summer in Amida and the Army had meant to have plentiful supplies of fodder from the surrounding land. Cutting off resupply thanks to Saladin’s corsairs made this impossible for the normal Roman logistics chain to address.

Accordingly, Alexios resolved to bait Saladin into attack. To do this he prepared a strong demonstration against the walls of Amida. Again and again they pressed, but Saladin refused the bait. This was starting to be a real risk, and Alexios’ generals divided themselves between those who supported an actual assault and those who felt that it was best and most appropriate to risk withdrawal.

Finally, after three weeks, Alexios made up his mind and ordered the withdrawal. The infantry, in lockstep rank, formed defensive positions against the advance of Saladin’s cavalry, as the Imperial cavalry formed into a wedge at the head and charged. Behind them, with measured turns of advance, the Georgians covered the baggage train and the Imperial infantry moved by turns. Saladin’s troops met the Imperial cavalry.

Alexios led from the front, as his ancestors and his adoptive father would have done. With his companions he pressed into the heart of the Muslim formation. By sword and lance, the heavy cavalry of the Empire, with the Georgians too and the knights of Antioch and Cilicia, forced Saladin back and cut through his cavalry. These disciplined troops had fought as well to withdraw as on the advance, and with ranks of pikes presented behind them, the infantry began to pass through.

Saladin rallied his troops and spun around to attack again from both flanks. They descended on the baggage train and the Georgians, and late in the day, forced Saladin’s left back. This opened a path for the Georgian infantry to escape, and the Sultan of Egypt was compelled to content himself with the act of destroying the Imperial siege engines. A second charge of Alexios’ rear-guard provided cover for the escape of the artillerymen, and the retreat carried on.

The next day the Army was bedraggled, and exhausted, and felt beaten. They still outnumbered Saladin, but the offensive had been an ill-timed exigency which had come to nought. Heralds from the Sultan of Egypt came to his position.

“O Emperor, His Majesty the Lord and Master of Egypt and the Syrias would treat with you!”

“I will hear his words under truce!” Alexios answered. He rode forward with a strong party, and Saladin did the same.

The bearded Sultan’s courtly bow in the saddle was met by a raised hand in salute, only. The Emperor of Rome admitted no equals. The men found common tongues and proceeded.

“You have come against the lands of the Muslims, and God has seen fit to allow me their defence,” Saladin observed. “We have ravaged your train and sent you in retreat.”

“You have lost me only some engines,” Alexios answered, “and the Army is still strong and in regular order, and in battle array to receive you. If you chose to continue hostilities, we stand in alliance with the Georgians as the stronger. However, I would see us negotiate a peace.”

“I would do so also,” Saladin agreed. “The Prince of Antioch is your vassal, is he not?”

“He is, and I expect any terms to include his lands beyond the Orontes,” Alexios answered.

“He raids the peaceful trade and travel of the Muslims from his forts beyond the Orontes,” was the reply.

“I shall forbid him this.”

“Then we might negotiate,” Saladin answered.

“Rome claims Acilisene, and the Georgians shall have Theodosiopolis, and their attendant lands,” Alexios presented his terms. “Then, we shall withdraw from the rest of the Emirates of Anatolia, and agree to terms of five years’ truce.”

“Leave the rulers of those places in their thrones, and I shall tolerate that they pay you tribute and send you troops for your other wars,” Saladin answered.

“Let us agree.”

1184

Constantinople

The Campaign of 1183 had proved a dubious endeavor. Though it had compelled the submission of Acilisene to Rome and Theodosiopolis to Georgia, and secured for Antioch its lands across the Orontes, that was trivial in the context of the Imperial frontiers. In Anatolia, at least, land directly controlled by the Empire was hardening around the old frontier with the Arab Caliphates in the centuries before the Macedonians, which was natural; there were many ruins of fortresses to rebuild, the lines of the mountains and hills had existed there for a reason.

That said, there had been victories. The truce secured the frontier, both Rome and Georgia had gained vassals in the north, and the Antiochene lands beyond the Orontes had been conceded by Saladin for the duration of the truce. This preserved Antioch as a defensive flank to the Empire.

Back at home in Constantinople, he had other things to deal with. The Cumans in Muntenia had revolted again, and another Army would have to be dispatched. His wife had given birth to a daughter, and the city had begun to grow again, not merely with Latin traders but with many Hungarians arriving from Hungary proper; with the King in the city, even with a Viceroy, there was a need for courtiers and audiences, many adventurers had gone to Anatolia, and Alexios’ decrees and Trans-Danubian campaigns had opened overland commerce, as well as boat traffic on the Danube, to heights it had not seen since perhaps the old days of the Empire.

From the heights of the Blachernae Palace, he was again together with his wife, looking down at a growing Hungarian community in the Imperial city. “We need somewhere to house them so we don’t have troubles between the nations,” Maria remarked. “My father always remarked the walls here were weaker despite his best efforts with their construction, but there was little thought to imagine it would cause trouble. The real heights are to the west, are they not?”

“Yes, at the monastery,” he gestured to the spot of gray amidst green beyond the walls. “A second course could envelop a neighbourhood for my Hungarian subjects, perhaps.”

“We could have it platted,” Maria suggested. “The inner walls could still have gates, so we could keep the communities separate when trouble comes to the city.”

“As it often does,” he chuckled. Maria’s efforts had not removed the feature of Latin riots and communal hostility, just put a damper on their escalation for a time. “I will have it platted, my wife,” he agreed. “And then we will have a Hungarian quarter.”

“Quarter of the Vardariotai,” she countered. “It will be good to build them a new barracks there.”

1185

Constantinople

The Norman emissary was dismissed after the usual complaints of their trading rights. For a century the Normans had not been trusted in the Empire, and with good reason. Their past invasion had been at a heavy cost.

“I do not trust their protestations of peace, but they are distracted with the King of the Germans, so perhaps it will be all,” Alexios remarked. He had sent an Army to Ancona this year, after the latest, and hopefully less transitory, success in campaign in Muntenia. The garrison had needed reinforcement, as one of the Seneschals of the German King was campaigning in the central parts of Italy in the continuing controversy with the Pope and the Cities for the control of Italy.

He had accordingly made General Branas the commander of the Army, and conveyed him on a powerful fleet to Ancona. With the son of the King in the Tuscan march and powerful armies directed against the Pope, this had provoked many emissaries from Italy, often with conflicting objectives.

Alexios’ aims were modest, however. Ancona was a protected city of the Empire, and so it would remain; but a proper defensive belt through the Marches would also see some good, and so he had authorised Branas to carry on and seize such strongpoints and receive the submission of such towns as would be suitable in Spoleto.

The Normans, facing a future with no heirs, had turned toward the Empire, and it seemed as if the King of Germany’s grasp was beginning to ensanre the south of Italy as well. Accordingly, Branas’ expedition was a first step toward a far more grave war, and in the end, the situation left Alexios thankful for the truce with Saladin. He might soon have the need to travel himself to Italy with a great Army in an effort to secure the situation there. The old dream of the Empire was not yet dead, and for the moment, papal intrigues in the east remained quiscent against the reality of the overweening threat of the Staufer.

1186

Teramo

At the confluence of the Vezzola and Tortino rivers, the town of Teramo was a ruin, marked only by a high tower. It occupied the indistinct territory in the north of Apulia, where the city had been sacked and annihilated by rival Norman factions only forty-six years before.

Here, Branas brought his small army of six thousand, accompanied by about a thousand Hungarian adventurers. A garrison remained behind to the north in Ancona, as he fenced and manoeuvred with the Army of the Germans under Markward von Annweiler, whom the German Emperor’s son had made Lord of Ancona (by pretence) and the Abruzzo. Since it was a known fact from the Imperial spies that there were negotiations between the Germans and the Sicilian King, the borders mattered for little.

Branas reflected grimly that the lone tower was like a grave to a city that should have still been Roman, part of his nation. This land should be his Emperor’s, not that of the Germans. Branas had drawn his troops up with the main body to the east of the hill south of the ruined city that dominated it and masked his men.

Markward was watering his men’s horses in the Vezzola. The hour was at hand. Branas raised his gloved fist, and tossed it forward. The German scouts were laying dead in the woods on the hill. His light detachment for ‘secret war’ duties had done their job. The sun of autumn glinted in the morning from his back, blinding the enemy in the direction of his army.

The Tagamata of the Nicomedian Serbs charged from the hill as the Hungarian cavalry lunged forward with General Branas’ own allagion of kataphractoi, fitted as western knights. The thunder of their hooves in the crisp autumn air masked the Nicomedian Serbs until they burst from the woods on the flank of the horse Markward had called by trumpet and drum to meet the onslaught of the Imperial horse.

The onrush of the Serbians crushed any cohesion that Markward’s Army might have. They overran the camp. Even though his horse came off the better in the tangle with Branas’, the Imperial cavalry smartly retired in good order back upon the rest of their infantry; when the German charge dissipated, they found their camp had fallen and their infantry had been dispersed. They could not scale the heights to the west, and to north and south strong detachments of enemy infantry in regular formation blocked them. To the east was the river.

Through midday, they attacked again and again, trying to break the infantry cordon. Branas re-formed his cavalry behind the southern infantry group and sent orders for his men to stand fast. He rested the horses and fed his cavalry. As the sun began to go lower in the sky again, the exhausted Germans turned to try and find a ford in the east across the river and escape.

It was at that moment Branas raised his fist again. This time there would be no quick or easy retreat. This was to close quarters and a general melee that the Imperial cavalry charged and swept Markward and his men from the field. The German King’s Minister escaped, but with him was precious few of his troops. The Imperial Cavalry had swept over them and crushed them, preventing escape except by a desperate un-horsed few who swam the autumn shallows of the river.

After Teramo, Conrad the Duke of Spoleto was forced to flee, and for the moment, Ancona was secure and the better part of Spoleto and the March was under Byzantine influence, though little outright control.

1187

Constantinople

The Emperor and the Empress sat side-by-side as co-sovereigns on their thrones in the Blachernae. Maria was pregnant again, though healthy enough yet to assume her place in the purple robes of state. Below them was a Latin delegation of men having come, priests and knights, from the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

“O Emperor, we bring terrible news from the south. The Sultan of Egypt has overthrown the armies of the King of Jerusalem. The King is the prisoner of the Sultan, and Saladin marches to put Jerusalem to siege.”

“Jerusalem was the rightful vassal of the Empire, being its lost lands,” Maria answered before her husband could. “The disobedience of the Frankish lords who seized those lands has been met with the Will of God, of which Saladin is only an instrument. My noble house and ancestors stretching back since they first assumed the throne held the right to those lands, by treaty and tradition, and if the Lords thereof had bowed to my father before God called him to the judgement, than the Imperial Armies should have long ago succored loyal vassals, and permitted them to preserve and enjoy the peace of the Holy Land.”

The priest stiffened and paced. He addressed Alexios, ignoring Maria. “O Emperor, recall that your ancestor was crowned Most Christian King. An advance now might save Jerusalem and the Holy Places, with the help of the Lord God.”

“I have made a truce with Saladin,” Alexios answered. “It does not expire for another year. Go first to the Pope. What will he guarantee Us? Shall the Empire not receive the same promises that the Frankish Lords have received? Will he commit to peace for those in the Marches in Italy who seek our light hand to avoid the onerous sins of the incessant war of Norman and German? Shall he respect the Christians of the East as brothers in Christ? Or shall the Frankish Lords come to the City and beg forgiveness for their disobedience and commit to rule their lands as fiefs of the Empire?”

1188

Constantinople

The answer had of course been “no” – at first. Then Jerusalem had fallen. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre had been used by Saladin to stable his horses, it was said, and many Christians had been sold into slavery and churches defiled. The Kingdom of Jerusalem was reduced to a single besieged city on the coast.

By the time it was done, the tune of the Latins had been changed. The Pope came with emissaries to Constantinople, proposing to recognise the Imperial dominance in Ancona and to enforce the truce of the Crusade on the possessions of the Hungarians and the Romans as well as the Franks and the Germans. Barbarossa was coming with his troops, and the Kings of France and England, all of Christendom was to be united.

Béla pressed on the matter of the allegiance of Jerusalem, but only received a promise that the King of Jerusalem should pass the overlordship of the County of Tripoli to him if he regained Jerusalem for Christendom.

Letters came from the Kings of the Germans, France and England. Alexios, for his part, sent one to the Georgians and Queen Tamar, for he thought the Georgians more important than the adventuring Knights of the west. The reply settled his mind and his plan.

Constantinople

Maria watched her husband’s coronation with the eyes of an eagle, scanning from threat to threat. It was a joyous day, the blessing of the Patriarch, the parades, the races in the Hippodrome and the jousts too. Enthroned at his side as co-ruler with her father, she had reached a pinnacle to all her aspirations. But in the audience she could mark out the threats:

There was the Protosebastos, and there was Andronikos Komnenos. There was Andronikos Angelos, and his young sons; and there was the youthful but old enough to be respected Alexios Doukas whose countenance well befit what Maria imagined Cassius might have. To some measure the better part of them were related to her; none of them were necessarily happy about Béla and all were threats to her children.

Each and every one of them might materialize into a threat. Her husband, her Alexios, would be the personification of the Empire, the Shadow of God on Earth, to the people; and a hammer on the frontiers. She... Would make sure that nothing touched her children. The Purple was the right of her family, and so it would remain.

Her serious countenance was appreciated by all during the ceremony, but expressed nothing. Without moving her eyes to admit the weakness during the high court ceremony, she still observed the expressions and countenances of every one of them. There were risks about, conspiracy in the air. While her father lived they might fear too greatly to conspire, but it would change. It always did.

1179

Esztergom

The Matter of Hungary had necessarily needed to be settled. Béla, to rule both Kingdoms, needed a steady and reliable hand on the tiller. To this he arranged the marriage of his sister Helen to Baldwin of Antioch, the son of Constance of Antioch and the Knight Raynald of Chatillon. The young man, only twenty-four years of age at Myriokephalon, had nonetheless been one of the ablest of Manuel’s commanders and had become a true bosom friend of Béla’s, a pure knight, but competent enough to restrain himself when needed, and much favoured by the old Emperor.

Béla had felt someone with a western connection was needed; he could not see one of the old Byzantine nobility doing anything other than causing dissensions in the Hungarian church. But Raynald was also a man of merely knightly origins and so to even marry the sister of a King was a great privilege for his son; by his countenance and by his station Béla did not fear him, especially that he was foreign to Hungary, and so, in a mirror of the position that he and his wife were to hold as Co-Sovereigns of both Rome and Hungary, he made his sister and her husband Baldwin Co-Viceroys of Hungary.

Béla had traveled to Esztergom with the return of the Royal Army’s expedition to support Byzantium, many contingents having remained campaigning in Anatolia for the past years, and others having seen many of the Knights and younger sons of Lords disperse to settle the good horse-land of central Anatolia. Anatolia was still a problem; the nature of the land had changed, with the central plateaus being reserved for horses. It was good land for the Hungarian settlers, but it had no ready Imperial administration; a few cities like Iconium had been reasonably prosperous under the Turks and it were now remitting taxes to Constantinople, but the rural expanses of the plateau itself would need years to recover and when they did, it would be as pronoia for Lords who found themselves with great cavalry grazing land. The tradition of being open plains horsemen was largely dead in Hungary, but the men who settled there would have to rediscover it. The old systems of agriculture had been lost to the Turkish administration, and by necessity the only way to bring it back under control was turn the whole of the highlands into a series of pronoia grants.

Returning to Hungary with the rest of the Royal Army, however, he did have reinforcements. Turks. A certain number of them had chosen to convert to Christianity when presented with the ruination of their state, and were allowed to summon their families and join Béla’s return home under arms. He had a plan for them, and it was a plan that he had executed on his return.

With a small Byzantine contingent to represent his authority in Constantinople and provide specialist engineering skills, he had crossed the Danube into the trans-Olt region and swept through the petty chiefdoms of the Cumans and the Vlach lords which represented the extreme end of Cumania. With little opposition he had established a series of posts along the Olt river and proclaimed the region the Banate of Severin within the Kingdom of Hungary. It was here that he settled the Turkic converts as well as some Cumans who chose to acknowledge his authority. Then at the end of the 1179 campaigning season he had carried on to Esztergom to witness the marriage of his sister and Baldwin and solemnize their position as Viceroys of Hungary.

The campaign had been almost desultory, since the trans-Olt was far from the centres of Cuman power and most of the land was in the power of petty Vlach Lords anyway. Without any significant battles, the power of being squeezed like a vice between the Roman lands and the Hungarian lands had made it a trivial exercise in the power of the new alliance to compel the submission of the local magnates, supply land to the settlers in a territory almost denuded of population, and then carry on through Transylvania and on to Esztergom.

The advance to Ersztergom was hardly a regular, shortest-distance course. Instead it became the character of a Royal Progress of the returning King and Army from victory against the infidel, visiting the towns and cities of the Realm of Hungary and receiving the homage of the people, from the Transylvanian mountains to the rolling Pannonian plain about the Danube. This was the land of his birth, and Béla took the necessary opportunity to hold a roving court, dispensing justice and hearing the complaints of the people.

Now, in Ersztergom in the fall, the brave young General of the Roman Army, but a Latin born of the Holy Land, was wed to his sister, and Béla raised his sceptre to proclaim them co-Viceroys for as long as he pleased of his Crownlands of Hungary, commending the diet to hear their laws passed in his name and obey their decrees. In the realm of his forefathers, used to traveling Kings, with his brother defeated, his Royal authority was sufficient to secure by acclaimation the arrangement, which provided a mirror of his own position of authority in Rome.

1180

Constantinople

When they found him dead, his courtiers and servants all agreed the expression on his face had been peaceful. He had died in the night, with his wife calling for the servants when she realised he was still.

Maria and Béla had come a short while later. Maria closed her eyes and stood beside her father, as the priests and deacons congregated, she followed along to the prayers of the dead. But there was something light in his countenance, it was true. For his entire life, the future of the Empire had been uncertain, the patrimony of Rome, the Empire that was a reflection upon Christ in Heaven.

Then, four years before, in the swirling dust of Manzikert, they had overcome the Turk, and marched on to Iconium and reclaimed it for the Empire. Now the border was what it was in the distant time of the Isaurians, or better. He had died in a measure of triumph, with the Empire at peace and the borders, thanks to her marriage, more secure than they had ever been. It was a Good Ending.

The Priests might have felt a less about it, though. Perhaps it was only Maria’s imagination but the dispute over the anathematization had been particularly bad, and that one was important because it touched on the matter of converts from the Turkish-occupied land, particularly the large number of Turks who had been willing to convert, and settle under Béla in the Banat of Severin. The Emperor’s preferences had prevailed, but Maria couldn’t help but feel that it was a bit of bad blood late in her father’s life that had been unnecessary to the political circumstances.

The procession ended in the Hagia Sophia, on an Autumn day with the Golden Horn and the Bosporus reflected in light. The censers filled the air with incense, smoky in the great church, entering the Imperial Gate one more time, her father was. This was the funeral of an Emperor; the chance to give an account of his life to God and to commend his soul to the mercies of Christ. But the Empire of Christ continued, and even here, even at her father’s funeral, she had to be prepared and ready for the conspiracies that might come.

At Maria’s influence the Parakoimomenos was a eunuch again and she had cause for that; as a woman of the palace she connected better with the eunuchs of the administration and had no disrepute for being in their presence long enough to properly plan, and they, without families of their own (especially the ones of foreign birth, as Tabakorios was), could be induced to support her for the interests of the Empire and the improvements of their comforts in this world and, if faithful, gains to the Church for the sake of the next.

Tabakorios, head lowered, allowed a subtlest of nods. The servants were in place who would secure the Hagia Sophia. Maria did not expect her enemies to move immediately nor in so holy of a place, for it would turn the Church against them when they might otherwise count on it as an ally, but she was prepared anyway.

Her husband’s complicated situation with religion was one that bore some reflection. Hungary was Latin, and the Empire, of course, was the Empire, with the Patriarchs of the East behind its profession. The disputes were because of the Pope who desired the overweening power of being both Pontifex Maximus and secular Emperor, there was little else that could properly describe their actions. Béla was trapped into a delicate policy of avoiding alienating the church in Hungary and respecting the faith of the Empire.

Of course, Hungary had a large number of Orthodox subjects as well, and the Empire necessarily maintained some Catholic churches for the benefit of the otherwise wild Italian merchants. That course was the one that Béla would have to dance most carefully on his own. He knew the latin church as one raised in it.

A part of her quailed at how she spent her father’s funeral, almost nervously obsessed with the potential for trouble, with the strategy surrounding her reign with her husband. She should be celebrating her father’s life instead. But he put me here, in an act of trust, and it could all be undone in a single hour of conspiracy.

Maria intended to be ready for it.

And as to what Manuel Komnenos thought of that, now judged by God on account of his contrition before the Lord of his heart and soul, that was between him, and God, and all the Emperors in heaven who had gone before. The two Sovereigns, clad equally in the regalia of Roman Sovereigns, observed together side by side, as husband and wife, the entombment of he who had gone before, the man who had set in motion everything that would matter about their lives.

Night settled over the Golden Horn, of a city that had never been this prosperous before, a city in a world that was returning to the ways of commerce and civilisation that had not been reached since the height of the days of Rome. Now, husband and wife would have to keep it.

1181

Constantinople in Summer

Following a strategy of cautious moves, Béla had combined his Hungarian and European Roman Armies into a single force in 1181, meeting in the Banat of Severin, and crossed the Olt. The next five months had consisted of a careful and methodical campaign into Muntenia beyond the Olt. To say that there was any real organised Cuman resistance was to exagerrate the organisation of their confederacy and its extension into those lands greatly.

At a ford on the upper Milcov in August, he had presented his combined Army against Cuman chieftains trying to fight him, and turned them back. Though the struggle at the Milcov ford was hardly decisive, it had begun to establish a new, tidy frontier for the Empire, defined by the limits of Muntenia, which unlike Oltenia—the Banat of Severin—he prepared to place under a Roman governor, for the first time across the Danube in many centuries.

At home, Maria’s first concern had been over the Church and the Latins. In general with Italy having calmed the situation with the west risked trouble, because the King of the Germans had a free hand to consider action against them. So far, though, their allied city of Ancona had not been threatened, the bigger problem was with the Republic of Venice.

Her father had, concerned over their commercial power, turned against Venice, using the pretext of attacks on the Genovese settlements in Galata. She had seen in the growing rivalry a seed of danger, and reached out to the Venetians through the usual cut-outs, after an exchange of letters with her husband on campaign. She proposed allowing them to build a settlement further up the Golden Horn from Galata. This would restore parity with the Genovese, but would also be more restricted than their position because of the lack of direct frontage on the Bosporus.

The diplomatic effort was important in the context of potentially needing to defend Ancona against the German King, and it was more importantly necessary, as she saw it, to secure the conspirators against her husband from having foreign help. Her spies were already busy; from the Post to the eunuchs of the palace that she had won over. The question was how much good it would do.

Constantinople, as winter comes

In the night, breath on the air was starting to become faintly visible. It was still reasonably warm, though, the gentle climes combined with the general warmth that had lasted as long as the Komnenos had ruled, perhaps a blessing from God. Others said it had been the same during the reign of the Macedonians.

Constantinople was a city of plenty, if not peace. As the entrepot to Europe for trade with the east, and once again as the metropole of a great Empire in Anatolia, the wealth continued to flow. The hundreds of thousands who lived in The City could see themselves as the heirs in comfort as well as culture of ancient times, enriched by the redemptive power of the Church.

The winter might be mild, but the emotions were anything but. The eunuch’s name had been Sayf as a child, but was now Marcian and under heavy palace robes and cloak the beginnings of the night’s chill did little hurt. There was considerable danger in the affair, but for a eunuch quick-witted conversation was the best way out of it (though Marcian was certainly capable with a dagger, and carried one).

Much of the Empress’ effort came down to this moment. A single passed message in the night. The hour is late. It was not the time. The details would remain unread, so much the better for the long-term survival of those involved.

-----

The Empress Maria was awoken almost immediately when the letter reached her in the palace. By flickering flame she read the delivered message. Her eyes flicked over it once, and then again. “The Vardariotai are still with us, as I expected. Have them use only whips against any mob put into the street, but make sure they are under full arms. The detachment of the Varangians shall secure the palace. All of the servants will be searched for hidden weapons.”

“As you command, O Empress!”

Though fewer and fewer Magyars were actually in the Vardariotai, one of the reasons that her father had placed them as the primary palace guard was their Magyar identity; with Alexios as his heir, the shared bonds created an esprit de corps even if it wasn’t really true. The Vardariotai, in some sense, because associated with the Party of the Magyars simply because everyone expected them to be. But Maria had leaned on that and made sure that her husband cultivated it into a real relationship, and now they were critical.

The revolt took the character of religious protests the next day instigated over the anathemas from her father, demanding their renounciation, and also a generalised pushback against a perceived ‘Latinisation’ threat pointed at her husband. They were turning out the people of the city as the cover to move troops and execute a conspiracy.

Of course it would be done when Alexios wasn’t present. The hero of Myriokephalon was seen as too dangerous, the rule of women inherently weak. The troops could be paid to eliminate him when he tried to use the Army to retake his city.

In a way, the game was as predictable as it was deadly. It was a matter of perception, where the party which won was the party which looked like to everyone on both sides that it was going to win. If it seemed like you had momentum, then you rapidly actually had momentum.

That was why putting the Vardariotai onto the streets with the dawn was critical. Before the mobs could even form up, these soldiers on horseback were waiting for them with their whips in hand, in uniforms of red. The Vardariotai drove forward against the forming groups and lashed them with their whips. Horses rearing and prancing, they mock-charged again and again in small squadrons, driving back the mob, whipped up by picked monks, with a combination of intimidation, mass and the whip. The clattering of hooves on the paving-stones thundered through the canyons of the high, red-roofed buildings.

“Come on lads, faster now!” Another right wheel and the horses spinning in a broad square, forming up and reins slapping and cracking, whips trailing down right as they charged into another group trying to occupy the square. They spun around at the last moment, a few of the crowd knocked down by horses but not many, and the rest subjected to a good whipping across the face as the Vardariotai slowed and rode along the front of the group. Part of their number peeled off and circled the mob, whips rising and falling with almost rhythmic cracks.

One squadron forced a group of ringleaders away from the mob they had raised, and circled them, constricting them into a little knot as their whips flailed down on their heads and faces mercilessly. Behind them, the mob dispersed before it had formed, bereft of momentum and leadership alike.

The main point of the mob, beside demonstrating momentum, had been to conceal the movements of the conspirators and picked bodies of men through the streets. Without the mob in place this collapsed, and soon the Vardariotai had the opporunity to avail themselves of their swords, as armed bodies moving through the city in contravention of the proclaimation which Maria had had the palace officials read at dawn were set upon.

As they were, a column of Varangians left the palace, moving quickly to the residence of the Patriarch, and pushing aside any resistance or opposition encountered along the way. They secured the environs while messengers from the Empress, eunuchs and officers riding protected amidst them, dismounted and respectfully entered with a message.

By noon on the clock, the city had calmed. The Vardariotai’s officers had been used to remove several commanders of the city watches and then the troops had been turned out to secure the gates. The critical thing now was to prevent an escape of the conspirators. Boats were secured, merchants were searched, and all gates save one, heavily guarded, were closed. Anyone leaving by that gate was again searched. The searches ultimately revealed what the letter had indicated. Andronikos Doukas and Isaac Komnenos had been implicated in the conspiracy, and the interrogations revealed that their hiding place was in the Venetian quarter.

But this was precisely why Maria had reached out to the Venetians. The situation was good enough now that instead of having participated in the abortive Coup, the Venetians handed the conspirators over. Put to the question, they implicated Isaac Angelos with themselves merely as catspaws, and Maria promptly had them blinded after the interrogations were complete. The first challenge to their reign had been dealt with. But Isaac had fled, and trouble would remain afoot.

1182

Varna

After the attempted coup, Béla had hastened back to the capital. He had done so only to find Maria and their three children safe and Maria firmly in control. He had presided over the remaining trials and then spent the winter seeing to the administration, and taking reports, including the succession disputes continuing in the Emirate of Mosul and the progress of the great Sultan of Egypt in Syria.

Béla had resolved not to be consumed by the internal dissensions. Part of being respected as the Empire of Rome was projection. Maria had handled the plot, Isaac Angelos had fled to Italy. He had taken the necessary steps to be ready and to remedy the deficiencies in the administration. That was all that was needed at the moment. It was better to look authoritative, permanently settling the defensive position of his realms.

In light of that, with spring, the continued restive nature of Muntenia meant that a second season of campaigning was required across the Danube. Again, contingents of the Roman and Hungarian Armies had gone forth into the fertile lands north of the Danube. There were Cuman bands to fight and there were strongpoints to establish, old roads to repair and bridges to fix, in a land that had been indifferently civilised since the height of the reign of the Good Emperors.

This was a kind of thankless campaigning, for it brought no great victories or glories. It was, however, necessary to obtain the design of a defensible frontier with the East and the steppe, in the dense network of rivers that grew from the mouths of the Danube east of Muntenia. And so the Army went forth.

Now, though, he had returned to territory he held with surety, at Varna on the Euxine Sea, and there was good reason for it. The Emissaries of King George of Georgia had come to him to treat on matters of interest, and he was inclined to meet them.

Originally, he had envisioned Georgia as a tributary state of his Empire. But the reality was that the Georgians themselves had grown great in their time of freedom, and were oppressed on many sides by enemies they needed to fight at all costs. Now, however, he met with the Georgians as allies. The restoration of Anatolia had proved no quick panacea, for the nature of the land had changed, and the effort to resettle it with Christian Lords and horsemen and to restore the tributary native Christian population to prosperity, to christianize the Turks that remained, would take time. Time during which it was best to hold the border at the old line through the Taurus mountains.

In that vein, he had accepted Georgian efforts at negotiations. Though the circumstances were nothing like what they would be in Constantinople, that worked in his favour to a certain extent. Surrounded by strong contingents of troops and on campaign, Alexios presented a muscular image of a man and King and Basileus in the prime of his life, leading his Army in person, used to the rigours of the Field. A squadron of the fleet stood in the harbour when the Georgian emissaries arrived.

What they revealed was that there had been considerable dissension among the Muslim Lords of Syria, and that the Sultan of Egypt had led a massive Army north to Syria, and had recently arrived in Damascus. The Georgians themselves felt that they could master the petty Emirates as far as Lake Van if the Empire supported their flank, but that they would need to act quickly for they thought that the Sultan of Egypt intended to secure the submission of all Syria and perhaps many lands further to the north.

Alexios felt that the situation was profitable, though he had little interest in attempting to expand into Syria, which promised a heavy price to hold; his only concern was to support his vassal of Antioch, which was threatened by Saladin, though he could see, in the rugged mountains secured on the flank by Georgia, some opportunity for the restoration of minor cities and valleys to the south of Trebizond. And so he offered to put an Army in the field for the campaigning season of the next year, if the Georgians would so the same. He would not make haste from one theatre to another.

After some discussion and appeal, the Georgians assented to the firm intentions of the Emperor, and the audience was concluded. A few months later, Alexios received a message from King George, affirming and accepting the terms of the operation, to muster armies for a campaign in eastern Anatolia for the campaigning season of 1183. Alexios then sent letters to his vassals of Antioch and Armenia, directing them to prepare their troops the coming year.

1183

Charpete

High in Eastern Anatolia, in lands defined by the bend in the upper Euphrates, an Army was marching. Thirty thousand troops, this was no small force. Contingents from Hungary were there, and the Armenians. Antioch, beset by foes, had not yet been able to detach her forces as Alexios descended with the standards of Rome against the forces of Diyarbakir. The Artuqids had rushed troops to face them here at Charpete, but they were the Lords of three cities of the East.

The Empire had something of the character of the Empire again. The Armies of the Artuqids were not so great. Banners and pennons fluttering, the light horse of the allied and tributary Cuman bands and converted Turks descended first with the heavy lancers of the Empire following down toward the city. The Hungarian lance, both from Pannonia and Anatolia, under their respective banners, glimmered in armour under the sun of early summer. Approaching from the West Southwest the rising sun of morning was in their eyes; it was the only advantage that the Artuqids had, drawn up on the plain south of the city.

And then their ranks began to panic. Cries came from them, something they could see and the Romans could not. After thirty minutes, they began to abandon their positions and flee to the south, without coming to contact with the Roman host.

The forward scouts, about fifteen minutes later, came charging back up toward Alexios’ camp, and within an hour he knew, for they came bearing messages. “The Georgians, O Emperor! The Georgians! They have come by way of Acilisene from the North!” Having overthrown Erzerum, the Georgians had continued their advance through the northeast while the Roman Army worked its way east of the fortress line. Now, as planned, they converged.

Alexios grinned and flung a mailed fist skyward. “With the blessings of Christ, for Amida we march!”

Diyarbakir

Of course, Saladin had not ignored the advance of the Roman and Georgian Armies. He had abandoned the siege of Kerak and marched north, bringing a great host which grew in numbers as he elected to sign an armistice with the Emir of Mosul as both were threatened. Leaving Diyarbakir—Amida—to defend itself, the remaining field armies of the Artuqids had fallen back and pledged themselves in homage to Saladin in exchange for his assistance.

These two Armies were concentrating for a clash of arms of considerable size. Alexios had advanced first, placing Amida and its black walls under siege. At the same time that he had put up the lines of circumvallation, however, defensive lines of contravallation also went up, the Antiochans providing information that Saladin was marching north. The area was fertile and water was easily diverted from several streams into their siege lines.

There were almost forty-five thousand Roman, Georgian and tributary troops at Amida; Saladin came with an army, including all of his allies to face the threat, of more than thirty thousand. Though outnumbered, he advanced confidently from the south toward the black-walled city. The Armenian Lord Sargis Zakarian was the commander of the Georgian Army and he favoured remaining in the fortified works against Saladin. The aged General Kontostephanos was the only one of his father’s great commanders with him; he favoured standing out for battle.

“It is ill to risk the water diverted or being trapped in place by the armies of the Sultan of the Egypt,” he explained. “O Emperor, we must be prepared to fight on our terms, not those of the enemy. There is no natural terrain to support our lines and an assault from the walls of Amida at the wrong time would halve our strength against the true threat—but the garrison is not strong enough to greatly add to Saladin’s array of battle if we can choose the terrain on which we fight.”

“Lord Sargis, do you have an answer?”

“We have plenty of water and supplies for weeks within the lines, O Emperor,” he answered. “The enemy will not know our resources or those of the enemy. He will risk the fall of the city if he does not attack, in our favour. Recall Caesar’s greatest triumph.”

“Alesia,” Alexios ran the word over his tongue. The writings of Caesar were mandatory knowledge for a King and an Emperor, but the vision of Gaul hung as a dim story. It was, on the face of it, sound strategy. But the Black Walls of Amida were far different from the situation at Alesia. He briefly considered attempting to storm the city before Saladin arrived, but that seemed a wild proposition. He had been raised to prefer the attack, but practical education in the Imperial court had shown him a different side to war.

“We will hold position.”

-----

Within the first week, Alexios had realised it was a mistake. Lord Sargis’ advice had been sound, in principle, but the moral effect of Saladin on the battlefield had not been accounted for. Instead it was a matter of the great enthusiasm people held for him. Amida was resisting stoutly, encouraged by the knowledge that Saladin was outside the walls. Saladin, for his part, made no attack on the contravallations, and contented himself with using his cavalry aggressively and skillfully to prevent raids and to prevent any kind of foraging of the combined Roman-Georgian Army; he was in for the long haul.

The problem was not food for the Army, of which they had had plenty. It was forage. The horses would be weak and, unable to charge properly, ultimately any break-out attempt would founder on the hunger of the horses, and the Army, even if it escaped, would be stuck without wagons, again for the want of fodder, to carry its own supplies. It was summer in Amida and the Army had meant to have plentiful supplies of fodder from the surrounding land. Cutting off resupply thanks to Saladin’s corsairs made this impossible for the normal Roman logistics chain to address.

Accordingly, Alexios resolved to bait Saladin into attack. To do this he prepared a strong demonstration against the walls of Amida. Again and again they pressed, but Saladin refused the bait. This was starting to be a real risk, and Alexios’ generals divided themselves between those who supported an actual assault and those who felt that it was best and most appropriate to risk withdrawal.

Finally, after three weeks, Alexios made up his mind and ordered the withdrawal. The infantry, in lockstep rank, formed defensive positions against the advance of Saladin’s cavalry, as the Imperial cavalry formed into a wedge at the head and charged. Behind them, with measured turns of advance, the Georgians covered the baggage train and the Imperial infantry moved by turns. Saladin’s troops met the Imperial cavalry.

Alexios led from the front, as his ancestors and his adoptive father would have done. With his companions he pressed into the heart of the Muslim formation. By sword and lance, the heavy cavalry of the Empire, with the Georgians too and the knights of Antioch and Cilicia, forced Saladin back and cut through his cavalry. These disciplined troops had fought as well to withdraw as on the advance, and with ranks of pikes presented behind them, the infantry began to pass through.

Saladin rallied his troops and spun around to attack again from both flanks. They descended on the baggage train and the Georgians, and late in the day, forced Saladin’s left back. This opened a path for the Georgian infantry to escape, and the Sultan of Egypt was compelled to content himself with the act of destroying the Imperial siege engines. A second charge of Alexios’ rear-guard provided cover for the escape of the artillerymen, and the retreat carried on.