I admit that this came out a bit longer that I wanted it to, but I couldn't help myself.

So without further ado, heres a love letter to a country that got some more attention and love itself in this version of the Madnessverse and a country that I hope to visit soon. Enjoy!

A History of the Republic of Norway

Part One: Demokrati

The nation of Norway has a long and storied history. However, the history of the modern nation of Norway did not begin until the Revolutions of 1844, one of which was the Norwegian Revolution, also known as the Norwegian War of Independence, a war which led to and coincided with the decline of the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway, a kingdom and personal-union which had existed for over four hundred years from 1523 to 1533 and again since 1537. Starting after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1814 and after years of the spread of revolutionary fervor and nationalism throughout Europe, a new movement of Norwegian nationalism and a Norwegian national consensus began to take hold within Norway, then a part of the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway. After almost three decades, the movement had continued to grow within intellectual and public circles within Norway, and at the start of 1844, the movement was finally starting to head to a climax.

On January 24, 1844, the Danish government of King Christian VIII and Prime Minister Poul Christian Stemann imposed a new series of heavy-handed taxes on the people of Norway, but not on the people of Denmark or any other territory of the kingdom. Six days later, on January 30, 1844, the Kingdom of Denmark passed laws that made military conscription for all males between the ages of 17-40 years of age mandatory within Norway, as it had been within Denmark since 1840. As a part of this law, at least one year of service in the colony of the Danish Gold Coast in West Africa was also mandatory. In recent years, a number of revolts in the Danish Gold Coast were causing problems and were forcing the Danish government to expend more money and men on the far-away and troublesome colony. Both of these laws, passed in such quick succession, caused outrage amongst the people of Norway. On February 13, 1844, numerous Norwegian citizens began protesting the new heavy-handed taxes and military conscription laws. The Norwegian people had had enough and decided to make their anger known to the government in Copenhagen.

King Christian VIII

Prime Minister Poul Christian Stemann

After weeks of protests, on February 27, 1844, a large group of Norwegian intellectuals, industrialists, businessmen, artists, clergymen and even common people signed a petition to the Danish government in Copenhagen and demanded that a new Norwegian constitution be written up, giving Norway more autonomy as its own constituent kingdom with its own parliament within the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway, including their own Prime Minister, to levy their own taxes, to make their own local laws, to end conscription, among other such demands. When the petition reached the government, these demands incensed King Christian VIII, who reigned with the absolute power that the Danish-Norwegian monarchs had ruled with for over four-hundred years. Thus, Christian VII was determined not to budge an inch and to keep his authority over Norway respected. Over the next few months, things remained tense within Norway between the Norwegian people and the Danish authorities.

On the morning of May 17, 1844, months after the refusal of the Danish government to recognize a Norwegian constitution, a group of Norwegian politicians, military officials, intellectuals, industrialists, businessmen, artists and clergymen, all in favor of either Norwegian autonomy within Denmark or full Norwegian independence from Denmark, meet in secret in a mansion on the outskirts of the town of Kongsberg. The two main leaders of the Constituent Assembly were Espen Kjell Halvorsen, the mayor of Kongsberg, and Thorlief Strand, a popular army general and veteran of the Gold Coast conflicts, both of whom were two of the most vocal proponents of reform within Norway. After hours of debate, it was decided that Norway would have to declare full independence from the Kingdom of Denmark and become an independent republic with its own constitution. Some hours later, the Constitution of the Republic of Norway was officially adopted, with the constitution establishing Norway as a republic with a semi-presidential system and a unicameral parliament and legislature known as the Storting. General Thorlief Strand was proclaimed the interim President of the Republic of Norway, while the office of Prime Minister was left vacant until election could be held int he future. Thus, in Norway the day of May 17th would become Norwegian Constitution Day or Norwegian Independence Day.

The Proclamation of the Norwegian Parliament, May 17, 1844

Espen Kjell Halvorsen (August 4, 1799-April 30, 1868)

Thorlief Strand (February 5, 1806-October 24, 1880)

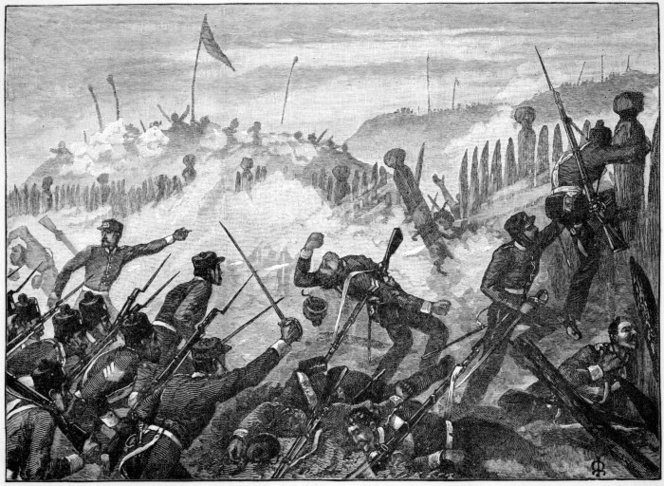

In the aftermath of the adoption of the Norwegian Constitution and the declaration of the Republic of Norway, King Christian VIII rallied the armies of Denmark, forged them into an expeditionary force under General Frederik Læssøe and then dispatched them across the Skagerrak to Norway. Upon their arrival, they were to arrest the leaders of the protests and the Constituent Assembly for treason and to burn all copies of the so-called Norwegian Constitution. Unsurprisingly, the Norwegian people weren’t going to allow the Danish Army to suppress their political desires, and armed confrontation soon turned into open street battles between Norwegian protesters and the Danish Army in the large cities of Norway. On May 24, 1844, only a week after the meeting of the Constituent Assembly, the Norwegian War of Independence began. The people of Norway soon began following Thorlief Strand, the proclaimed provisional president of Norway, and he began to be held up by the Norwegian people as their leader and became the public face of the Norwegian Rebellion.

Frederik Læssøe, leader of the Danish armies in Norway

President and General Strand and the provisional government of the Republic of Norway soon began receiving secret funding from the Kingdom of Sweden under King Oscar I. The Scandinavian nations of Sweden and Denmark had a long, shared history with a long, heated and storied rivalry, with over ten wars between the two nations between 1521 and 1789, with the two nations having been at war with each other at almost every chance between 1448 and 1789. As a result, the Swedish government decided to fund the Norwegian rebellion in an effort to weaken their longtime rival of Denmark and to attempt to bring about an end to Danish power in Scandinavia once and for all. With this new flow of cash coming in from Sweden, the Norwegian provisional government purchased new weapons and supplies from the Commonwealth of England, as well as other nearby nations such as Scotland and Prussia. In August, 1844, Strand called for international volunteers to help, in his words, “combat the cancer of absolute monarchy and bring about a Norwegian Republic.” As a result, thousands of English and American volunteer veterans of the recent English Revolution (sometimes called the Second English Revolution, with the English Civil War of the 17th century being the First English Revolution) crossed the North Sea, landed in Norway to joined Strand's forces. Reverend Milo Miles led the American Fundamentalist Brigades, while General Thomas Foxbridge led the "Cromwellite Volunteer Republican Army." Other volunteer forces came from other Protestant nations in Europe, such as Prussia, the Netherlands, Finland, the North American Southron nations and the Protestant regions of the Rhineland and Switzerland. Some volunteer forces even came from non-majority Protestant nations such as the Franco-Spanish Empire, Portugal, the Italian states, the Austrian Empire and the Russian Empire, among others, with the volunteers simply being sympathizers to the cause of Norwegian Independence, Liberalism and Republicanism.

Thomas Foxbridge (June 5, 1812-September 29, 1870), leader of the "Cromwellite Volunteer Republican Army"

In December, 1844, the Norwegian Army, with the help of the newly-established International Volunteer Brigades (Internasjonale frivillige brigader) launched the Winter Offensive (Vinterstødende), kicking the Danish armies out of the port cities of Bergen and Haugesund, thus raising the morale of the Norwegian armies and people. On March 20, 1845, after a lull in fighting during the harsh Norwegian winter, the Siege of Trondheim began. To the south, with much or the Danish forces in different parts of southwestern Norway isolated, a new two-pronged offensive began to secure the rest of the Norway for the revolutionaries. On March 29, 1845, the Battle of Molde began, with the city surrendering on April 9, 1845. On March 31, 1845, the Battle of Stavanger began, with the city surrendering on April 14, 1845. After that, more cities fell; Alesund fell on April 20, and then Floro fell on April 24. After an almost two month-long siege, Trondheim fell to the Norwegian rebels on April 28, 1845. Throughout May, 1845, most of the Danish held-towns and garrisons in the sparsely populated regions of northern Norway began to gradually fall to the Norwegian rebel armies. As revolutionary fervor swept Norway, Denmark was starting to feel the burden of fighting both in Norway and in the Gold Coast against a number of rebellious African tribes, such as the Ashanti, Akan, Ga, Gonja and Ga-Adangbe. Strand hoped that by fighting a war of attrition against Denmark, the Danish Armies would finally pull out of Norway and focus on trying to stabilize their colony of the Gold Coast. On May 14, 1845, after months of the Danish fighting the Norwegian rebels, the Republic of Iceland was declared independent from the Kingdom of Denmark, and Greenland then declared independence from the Kingdom of Denmark on June 6, 1845. On June 6, 1845, with the mounting causalities of Danish soldiers, with numerous Danish soldiers in Norwegian towns and forts under siege and with the prospect of bankruptcy facing the Danish treasury and government, Christian VIII decided to back down and recalled the Danish armies under General Frederik Læssøe back from Norway to Denmark. By the end of the month, all of the Danish soldiers had either retreated from Norway or surrendered to the Norwegian rebels. On July 1, 1845, the Kingdom of Denmark officially recognized the independence of Norway, as well as Iceland and Greenland. As a result, the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway was officially disbanded after 408 years of continual existence, and the Kingdom of Denmark was established in its place. On July 9, 1845, the Republic of Norway was diplomatically recognized by the Kingdom of Sweden. On July 12, 1845, the Republic of Norway was diplomatically recognized by the Franco-Spanish Empire. The Republic of Norway was then diplomatically recognized by Prussia, England, the Confederation of the Rhine, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Ireland, Scotland, Wales and the Russian Empire.

In the first years of Norwegian independence, partly under the presidency of Thorlief Strand from 1844 to 1852, Norway began to establish diplomatic relations with a number of other nations. Norway had very good relations with its immediate neighbor, the Kingdom of Sweden, as it was a fellow Scandinavian neighbor with a long and shared history and a major supporter of the Norwegian Revolution. Norway also had very good relations with the other Protestant nations in Europe, such as Prussia/the Nordreich, the Netherlands, England, Scotland and Wales. Norway also had very good relations with the Franco-Spanish Empire and her client states, as the Franco-Spanish Empire was one of the first nations to recognize the independence of Norway. Norway also had good relations with Iceland and Greenland. For obvious reasons, Norway had cold relations (no pun intended) with its former master of Denmark. However, as the decades progressed, relations between the two Scandinavian and Protestant nations would gradually improve. Across the Atlantic, the Republic of Norway had somewhat good relations with the Republican Union. However, they were still somewhat cold relations, as the Norwegian government and the vast majority of the Norwegian people viewed the American Fundamentalist Christian Church, a religion which had a lot of influence over the Union government and culture, as a bizarre, unchristian and potentially dangerous cult. As a result, the Republic of Norway decided to have cordial relations with the Republican Union, but at the same time, decided to keep the Republican Union at a metaphorical arm’s length. In regards to the rest of the new world, Norway also had somewhat better relations with the Southron nations of Virginia, Maryland, CoCaro and Georgia, as well as the nations of Latin America.

The first elections in Norwegian history were held in 1848, and in the elections President Strand won in a massive landslide against his old friend and friendly rival Espen Kjell Halvorsen. In one of his last major acts as President and Founding Father (

Grunnleggeren, an unofficial honorary title) of the Republic of Norway, President Strand adopted an official national anthem for the Republic of Norway. In 1850, on the directive of President Strand, the Norwegian patriotic song

Norges Skaal (Norway’s Toast), written in 1771 by the Norwegian poet, dramatist, political and Bishop in Bergen Johan Nordahl Brun (1745-1816) and a song that was immensely popular amongst the Norwegian rebels, was officially adopted as the national of anthem of Norway, and was to be sung at public events, diplomatic events and at commemorations on Norwegian Independence Day, among other such functions. The next elections were held four years later in 1852. Frederik Due, a former Norwegian military officer, veteran of the Gold Coast Campaigns in West Africa and the Norwegian War of Independence, won the election for the newly-established Liberal Party (

Liberale partiet). Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, the Liberal Party continued to be the dominant party within the realm of Norwegian politics, and the party managed to uphold the Liberal, Republican and Secular values of the republic. Under President Due, a number of land reform bills were passed in the Norwegian Storting and then implemented throughout the rural regions of Norway. All of this changed with the election of 1864, which saw the defeat of President Due and the election of Georg Sibbern, the leader of the Norwegian Conservative Party (

Konservative partiet), to the Presidency of Norway. The Sibbern presidency lasted for eight years and saw the passing of new tariffs in an effort to improve the Norwegian economy and the increasing of the budgets for the Norwegian army and navy. It was also during his presidency that military advisers and officers were invited from numerous foreign nations, such as Prussia, Sweden, Russia, France-Spain and Austria, to help improve the fighting capability and tactics of Norwegian Army and Navy. In the election of 1872, the Liberal Party returned to power under the rule of President Ole Jørgensen Richter, who defeated President Sibbern in the election, as most Norwegians had begun to tire of eight years of conservative leadership. One of the first acts of Richter's presidency was to remove most of the Sibbern-era tariffs. However, Richter continued to keep the same amount of funding for the Norwegian Army and Navy that President Sibbern had first set up.

Frederik Due

Georg Sibbern

Ole Jørgensen Richter

By the 1870s and 1880s, in spite of being a minor power on both the European and World stages, the Republic of Norway was one of the great success stories amongst the European nations. During the last decades of the 19th century, Norway gained a reputation as being one of the most liberal and progressive nations on the continent of Europe. Norway had a republican and enlightenment-inspired constitution which enshrined numerous liberal and enlightenment values such freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of the press, rights for all citizens regardless of race, nationality, gender or religion, separation of church and state, among others.

In the decades after its independence, Norway experienced a new Norwegian Cultural Renaissance (

Norsk kulturell gjenfødelse). This was a new birth of Norwegian culture in the form of literature, art and music, much of which was done in the style of Norwegian romantic nationalism (

Norsk Nasjonalromantikken), a style which emphasized a Norwegian aesthetic, in the aftermath of the independence of Norway. For centuries, during the personal-union between Denmark and Norway, with Denmark as the major partner of the union, Norway became a cultural backwater, with a large amount of brain drain leaving Norway for Denmark and a distinctive Norwegian culture being found only amongst the farmers and peasants in the rural regions of Norway. After the independence of Norway, the creation and maintaining of a new and distinct Norwegian cultural identity became a major priority for the Norwegian government and cultural society. As a result, the governments of numerous Norwegian presidents, along with numerous Norwegian cultural institutions in Oslo, Bergen, Stavanger, Trondheim, among other cities, began promoting the arts within Norway and collecting artifacts and cultural practices from the rural regions of Norway. This was all in an effort to preserve a distinct, identifiable Norwegian identity and culture, not just for Norwegians themselves but for the rest of the world as well. This resulted in the creation of new works of art, literature, theater and music within Norway.

Some off the main figures of the Norwegian Cultural Renaissance were writers, be they novelists, poets or playwrights, such as Henrik Ibsen, called by the Virginian-born author Samuel Clemens as "the Norwegian Shakespeare", Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Jonas Lie, Johan Sebastian Welhaven, Amalie Skram and Henrik Wergeland, linguists such as Ivar Aasen, artists such as Adolph Tidemand, Hans Gude, J.C. Dahl and August Cappelen, and composers such as Edvard Greig, the violinist and composer Ole Bull and the composer, conductor and violinist Johan Halvorsen, who made a well-publicized debut playing violin at a theater in Oslo at the age of twenty-one in 1885. In particular, Edvard Greig produced a number of pieces of classical music that became world famous, such as "

In the Hall of the Mountain King" (

I Dovregubbens hall) and "

Morning Mood" (

Morgenstemning), both written for the 1867 play Peer Gynt by the aforementioned Henrik Ibsen. The music of Greig would also become popular within the Republican Union, where it was held up as an example of "fine, Protestant-inspired music", as stated as such by Union Secretary of Education Thomas Edison. In edition the creation of new arts, the old and traditional arts of Norway, be they folktales or folktunes, were also collected and preserved by numerous Norwegian intellectuals, writers, musicians and artists. It was also during this period that new Norwegian patriotic songs were written and composed. One of the most popular of these was "

Ja, vi elsker dette landet" (Yes, we love this country), written in 1862 by the aforementioned Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, with music by a young Norwegian composer named Rikard Nordraak. Another one of these songs was "

Gud signe vårt dyre fedreland" (God bless our precious fatherland), written in 1891 by the professor, theologian, church councilor, hymn writer and Liberal Party politician and unsuccessful 1880 presidential-candidate Elias Blix. In 1894, his name would be given to the Blix Prize, a prize presented by the Norwegian Literacy Society for the best writer and the best novel written and published within Norway.

Brudeferden I Hardanger (Bridal party in Hardanger), Hans Gude and Adolph Tidemand, 1848

A Painting by Hans Gude, 1847

Fra Vossevangen, Hans Gude, 1860

The 1870s and 1880s saw numerous new political developments within the Republic of Norway, such as the establishment of new political parties within Norway, such as the Christian Democracy Pa

rty (Kristendemokratipartiet), founded in 1874, and the Centrist Liberal Party (Sentrumsliberalepartiet), founded in 1878,

both of which broke away from the Conservative Party. In 1876, Emil Stang of the newly established Christian Democracy Pa

rty was elected President of Norway. His presidency saw the financial support of numerous Protestant and Lutheran charities, including orphanages and hospitals, throughout Norway. In 1880, Christian Homann Schweigaard of the Conservative Party was elected President of Norway, thus returning the Conservative Party back to national power in Norway. One October 24, 1880, Thorlief Strand died of a heart attack in his vacation home in Alesund at the age of 74. His body was then sent by a funerary train to Oslo. On November 5, 1880, the funeral of Thorlief Strand, the largest and most grand in Norwegian history both up to that point and since that point, was held and conducted throughout the city of Oslo. His body was then buried in an elaborate mausoleum, with both Greco-Roman and Nordic motifs, located outside of the city and built in 1872 for the occasion of his eventual passing.

Emil Stang

Christian Homann Schweigaard

On June 20, 1881, after d

ecades of industrialization in Norway and with many Norwegians from rural regions moving into urban areas and cities and being subjected to horrific working conditions, the Workers Party (Arbeiderpartiet) was founded by a number of trade unionists, socialists and other left-leaning politicians, mostly in the cities and industrial regions of Norway. The first leader of the Worker’s Party was the trade unionist, typographer, newspaper editor and book publisher by the name of Christian Holtermann Knudsen. Before long, members of the Workers Party would be elected to the Storting, and afterwords would sponsor numerous progressive and pro-labor bills in the Storting. All of these efforts to sponsor progressive and pro-labor bills would soon see success. In the 1884 presidential election, Johannes Steen of the Liberal Party was elected President of Norway. Steen was an outspoken social reformer and a supporter of both women's suffrage, labor reform and social capitalism. In 1886, under President Johannes Steen and with the cooperation of the Workers Party, the Norwegian Storting passed a series of strict worker protection laws. One year later, in 1887, the Storting, with the full support of President Steen and the Workers Party, passed a law which set both a minimum wage and an eight-hour work week within Norway. It was also during the 1880s that the ideas and philosophy of social capitalism, as theorized by the Prussian philosopher Friedrich Engels, gained a large following amongst numerous intellectuals, industrialists and other businessmen within Norway, both in cities and in rural areas. Beginning in the 1880s and continuing into the 1890s, many Norwegian industrialists, factory-owners, farmers, landowners and businessmen began to implement the ideals of social capitalism and to put them into practice within their own companies, factories and/or farms.

Christian Holtermann Knudsen, first leader of the Arbeiderpartiet

Johannes Steen

In the election of 1888, with the popularity of the Liberal Party at an all-time high amonst the Norwegian people, Ole Anton Qvam of the Liberal Party was elected President of Norway. Under President Qvam, the progressive policies of President Johannes Steen the would continue to be implemented, and new policies would also be implemented. In 1890, under the presidency of President Ole Anton Qvam, Norway became the first nation in the world to give women suffrage and the right vote, much to the chagrin of most members of the Conservative Party and the Christian Democracy Pa

rty, most of whose members were not in favor of women’s suffrage. Thus, Norway continued to maintain its worldwide reputation as a liberal, open and progressive country and, in the words of the Spanish-born Carolinian philosopher, historian and Duke University professor George Augustus Santayana, "an island of prosperity and calm alone in a sea of massive, jingoistic and expansive empires." It was also during the Presidency of Ole Anton Qvam that relations between

Norway and the Republican Union began to worsen as the result of alarming reports of massacres and killings in "Old Mexico" coming from Norwegian journalists who traveled through and reported about developments in Union-annexed Mexico (all of which the Union government of President Custer vehemently denied), as well as the ongoing Union wars of expansion in islands of the Pacific Ocean, which President Qvam stated were "unjust and unnecessary." While President Qvam tolerated and allowed AFCC Missionaries to stay and conduct activities within Norway, there was a lot of tension between the AFCC missionaries and the clergymen of the many traditional Norwegian Protestant churches. As a result, in an effort to prevent further such problems and a potential religious conflict, in 1888, in one of his last acts as President, Qvam helped to pass a number of laws which would prevent any AFC Missionaries, as well as most other foreign religious missionaries, from coming into the country and proselytizing their religions within the Republic of Norway.

The decade of the 1880s, as well as the beginning of the 1890s, was an overwhelmingly peaceful era for the Republic of Norway. However, as the 1890s continued on, the Norwegian economy began to struggle both internally and externally, as domestically-made Norwegian goods could no longer compete on the intentional market with foreign goods from larger, richer nations with large, expansive empires such as Europa, the Nordreich, the Netherlands, the Russian Empire and the Republican Union. In the election of 1892, Otto Blehr of the Centrist Party was elected President of Norway. A year later, in 1893, the Norwegian economy began to stagnate even more, and this began to the effect the lives of average, everyday Norwegians, both in the cities and the country. Thus, this was the beginning of the Norwegian Economic Crisis. Things began to change, and not for the better. This economic stagnation led to a number of developments. Outside of Norway, it led to the emigration of a number of Norwegians to nations such as the Republican Union, the Confederation of the Carolinas, Quebec, French Canada, Gran Colombia, Peru, Brazil-Rio de la Plata, Australia, French Australia and Dutch Africa, among other places. Within Norway, it led to quite a bit of instability, such as workers strikes at factories, mines and quarries, protests outside of workplaces, and protests by far-left and far-right political parties. On numerous occasions, the Norwegian police, and on some occasions even the military, had to break up worker strikes and street fights between different political parties and paramilitary groups. During the 1890s, radical violence and clashes between far-left and far-right increased within Norway. After the last big political clashes in 1895, things began to calm down in Norway, much to the relief of many Norwegians. However, the damage was done, as President Blehr was seen as in ineffective and incompetent leader who did nothing to help the lives of average Norwegians or to help to unify the Norwegian people. Thus, this peacefulness amongst continual economic stagnation would not last for all that long.

All in all, the first five decades in the history of the Republic of Norway were decades of freedom, liberalism, prosperity, culture and democracy, with the emergence of new political parties, the passing of new, progressive pieces of legislation and a new flowering of culture and the arts to go along with this political openness and diplomatic peace. However, with the year that was 1898, all of this was about to change with the emergence of a ex-army officer and university professor by the name of Thorvald Njord Holgersen and the Norwegian People's Fascist Party (Norsk Folksfascistparti).