A few years ago I started this thread: https://www.alternatehistory.com/forum/threads/wi-allied-victory-in-the-battle-of-crete.415360/. We had a good discussion and I toyed with the idea of making something more out of it. With a thread on the same subject going up recently and with social isolation still in the portrait I decided to give it a go

The Spirit of Salamis- A Short Allied Victory in Crete TL

Prologue: The Genesis of Operation Mercury and the Creation of the Creforce

When studying World War II as a whole a scholar might be forgiven to first look for the origins of Operation Mercury (the German attack on Crete) in the military situation as a whole and to look for Germans' motivations in how a successfull attack on Crete might have helped the Afrikakorps and the upcoming Operation Barbarossa, or more simply in a desire to finish expulsing the allies from the Balkans. While these factors indeed played a role in Nazi Germany's decision to attack the island, we must look elsewhere, mainly in the incessant feuds of the different factions and organisations inside the Nazi state, to understand the origins of Case Merkury.

The Kriegsmarine proved to be the greatest champion of the operation, hoping to see it repeated in Malta, Cyprus and/or Gibraltar, and therefore possibly heralding the rise of the Medditerannean strategy championned by its commander's, Admiral Raeder. Moreover, Mercury also enjoyed the support of the Luftwaffe: as a result of the success on the Raid of Taranto and the British victory at Cape Matapan only the Fallschirmjäger (1), as well as the Luftwaffe's domination of the skies of Crete, could show that she could serve as the backbone of a German invasion. Mercury was therefore seen by Goering and his subordinates as a way for the Luftwaffe to regain some of the prestige lost over the skies of Britain a year before. The number two of the Nazi regime therefore threw his still considerable political weight behind the operation. The Heer and the OKH, on the other hand, strongly opposed the planned invasion, believing that even in victory the Luftwaffe and the Fallschirmjäger would suffer severe looses that would hinder their ability to properly support the ground forces during the upcoming invasion of the USSR and pointing the inherent risks of Mercury, as conducting a major offensive with mainly airborne power had never been attempted before. Thus, its opponents characterized the invasion of Crete as a dangerous distraction. In the end it was Hitler himself who ended the debate in favour of Mercury, the Nazi dictator deeming it a usefull diversion to distract Stalin's attention from Barbarossa's preparations.

Similarly, doubts were raised in the British camp as to whether Crete should or could be defended. Lead by the CnC Middle-East, General Archibald Wavell, some argued that, with operations Battleaxe (the British counterattack against Rommel and the Italians in Lybia) and Brevity (the assault on Vichy France-held Syria and Lebanon) set to soon begin, while the German-friendly Iraqi government of Rachid Ali and the Italian forces continued to resist, the forces needed to defend Crete were simply not available in the vicinity. Winston Churchill himself put an end to such talks, however: a Crete in German hands would threaten the Mediterranean supply lines to Alexandria and the political consequences of abandoning the island to its fate could not be overstated. Crete would be defended. To do so a ragtag and disparate group of units were gathered. The Creforce, as it was dubbed, was assembled around the 2nd New Zealand Division (its commander, General Freyberg, also commanded the Creforce as a whole), the equivalent of another, small, division in greek troops evacuated from the continent, a british brigade, a few Australian brigades having suffered during the Greece campaign, and a few small tanks and marines units. When all was said the Creforce could pass for the equivalent of an army corps, and therefore be able to oppose the German paratroopers on, if not equal footing at least something approximating it.

As May 1941 entered its second half ULTRA informed the allies in general, and General Freyberg in particular, that the invasion was soon to come. As the outcome of the battle would rest on Germany's ability to supply and reinforce its paratroopers fighting was bound to center around the military airfields of Malemme, Rethymon and Heraklion airports and, to a lesser degree, the harbours of Chania and Suda some voices in the headquarter of the Creforce rose to demand that the airfields be disabled but Freyberg firmly vetoed the idea, fearing that to do so would allow the germans to deduce that their code had been deciphered. For General Freyberg the last days before the beginning of Mercury were spent preparing the defense of these five key points, sending the last air forces still on the island away (as they could not hope to compete with Germany's air superiority) as well as to decide who was to replace Brigadier Hargest at the head of the 5th New Zealand Brigade, following his sudden departure from service following a heart attack (2).

In the early morning of May 20 1941 the first german gliders where spotted by the Creforce, the Battle of Crete was about to begin.

Excerpt of Crete 1941: Germany's First Defeat on Land.

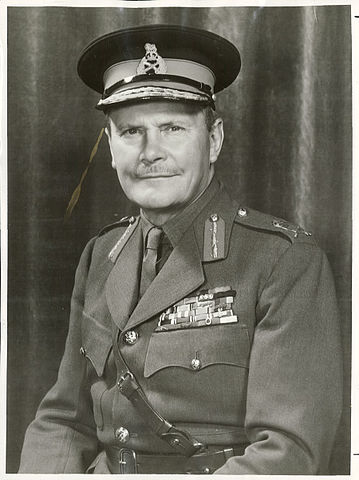

Generals Freyberg and Student, commanders of the Allied and Axis forces during the Battle of Crete

(1) The German airborne corps.

(2) The POD.

The Spirit of Salamis- A Short Allied Victory in Crete TL

When studying World War II as a whole a scholar might be forgiven to first look for the origins of Operation Mercury (the German attack on Crete) in the military situation as a whole and to look for Germans' motivations in how a successfull attack on Crete might have helped the Afrikakorps and the upcoming Operation Barbarossa, or more simply in a desire to finish expulsing the allies from the Balkans. While these factors indeed played a role in Nazi Germany's decision to attack the island, we must look elsewhere, mainly in the incessant feuds of the different factions and organisations inside the Nazi state, to understand the origins of Case Merkury.

The Kriegsmarine proved to be the greatest champion of the operation, hoping to see it repeated in Malta, Cyprus and/or Gibraltar, and therefore possibly heralding the rise of the Medditerannean strategy championned by its commander's, Admiral Raeder. Moreover, Mercury also enjoyed the support of the Luftwaffe: as a result of the success on the Raid of Taranto and the British victory at Cape Matapan only the Fallschirmjäger (1), as well as the Luftwaffe's domination of the skies of Crete, could show that she could serve as the backbone of a German invasion. Mercury was therefore seen by Goering and his subordinates as a way for the Luftwaffe to regain some of the prestige lost over the skies of Britain a year before. The number two of the Nazi regime therefore threw his still considerable political weight behind the operation. The Heer and the OKH, on the other hand, strongly opposed the planned invasion, believing that even in victory the Luftwaffe and the Fallschirmjäger would suffer severe looses that would hinder their ability to properly support the ground forces during the upcoming invasion of the USSR and pointing the inherent risks of Mercury, as conducting a major offensive with mainly airborne power had never been attempted before. Thus, its opponents characterized the invasion of Crete as a dangerous distraction. In the end it was Hitler himself who ended the debate in favour of Mercury, the Nazi dictator deeming it a usefull diversion to distract Stalin's attention from Barbarossa's preparations.

Similarly, doubts were raised in the British camp as to whether Crete should or could be defended. Lead by the CnC Middle-East, General Archibald Wavell, some argued that, with operations Battleaxe (the British counterattack against Rommel and the Italians in Lybia) and Brevity (the assault on Vichy France-held Syria and Lebanon) set to soon begin, while the German-friendly Iraqi government of Rachid Ali and the Italian forces continued to resist, the forces needed to defend Crete were simply not available in the vicinity. Winston Churchill himself put an end to such talks, however: a Crete in German hands would threaten the Mediterranean supply lines to Alexandria and the political consequences of abandoning the island to its fate could not be overstated. Crete would be defended. To do so a ragtag and disparate group of units were gathered. The Creforce, as it was dubbed, was assembled around the 2nd New Zealand Division (its commander, General Freyberg, also commanded the Creforce as a whole), the equivalent of another, small, division in greek troops evacuated from the continent, a british brigade, a few Australian brigades having suffered during the Greece campaign, and a few small tanks and marines units. When all was said the Creforce could pass for the equivalent of an army corps, and therefore be able to oppose the German paratroopers on, if not equal footing at least something approximating it.

As May 1941 entered its second half ULTRA informed the allies in general, and General Freyberg in particular, that the invasion was soon to come. As the outcome of the battle would rest on Germany's ability to supply and reinforce its paratroopers fighting was bound to center around the military airfields of Malemme, Rethymon and Heraklion airports and, to a lesser degree, the harbours of Chania and Suda some voices in the headquarter of the Creforce rose to demand that the airfields be disabled but Freyberg firmly vetoed the idea, fearing that to do so would allow the germans to deduce that their code had been deciphered. For General Freyberg the last days before the beginning of Mercury were spent preparing the defense of these five key points, sending the last air forces still on the island away (as they could not hope to compete with Germany's air superiority) as well as to decide who was to replace Brigadier Hargest at the head of the 5th New Zealand Brigade, following his sudden departure from service following a heart attack (2).

In the early morning of May 20 1941 the first german gliders where spotted by the Creforce, the Battle of Crete was about to begin.

Excerpt of Crete 1941: Germany's First Defeat on Land.

Generals Freyberg and Student, commanders of the Allied and Axis forces during the Battle of Crete

(1) The German airborne corps.

(2) The POD.

Last edited: