Political chaos: the bloody end of 1971 and the hard beginning of 1972

Tierno Galván's tenure is best remembered by his successful reforms of the welfare state and by his legalization of the trade unions during his brief tenure (March 24 - December, 9, 1971). He began by passing important pension and workman's compensation laws. Then, in April, he also extended coverage of family allowances to practically the entire population,

and, in October, he expanded the insurance of occupation risks "

would henceforth be mandatory and that such insurance would be granted by the Social Security". His last triumph would come in November 1971, with a law that regulated collective bargaining, and contained a guarantee of the right of workers to strike; this law also fixed minimum wages for agriculture and for industry. However, what eventually brought down Tierno Galván was his inability to find a solution to the Catalan trouble. About him and this issue, the US Ambassador in Madrid,

Robert C. Hill, said that Tierno was "a deeply harassed man" [...] "on the verge of a nervous breakdown". Caught between his desires to end the war and to maintain Spanish rule over Catalonia, he vacillated between pressing the war, perhaps by asking the British for an increased support, or seeking a negotiated solution.

Thus, while Tierno doubted and was unable to choose one of the two options, the Catalan Army further divided itself. As López Raimundo kept pressing for a

Marxist class struggle outlook, a sizeable part of

Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC; Republican Left of Catalonia), broke with ERC after branding its leadership as "lapdogs of the bourgeoisie", and joined López Raimundo to create the

Partit dels Treballadors (PT, Workers' Party); with them went also a small part of the regular and irregular forces of the Catalan Army, thus creating a paramilitary force, the

Voluntaris Catalans (VC- Catalan Volunteers). The VC would begin with bringing the war outside Catalonia: a VC

active service unit based in Madrid carried out a series of armed bank robberies during the summer of 1971 to raise funds for the VC; this unit would exist until 1974, when most of its members left the VC and joined the Catalan Army.

The fall of Tierno began in October. Federico Jiménez Losantos (1951-1971), a member of the

Organización Comunista de España (Bandera Roja) -Communist Organization of Spain (Red Flag)-, was arrested on October 21 when the police crushed with extreme violence a demonstration demanding religious freedom and having the Catalan language taught in the schools of Barcelona. A few days later (October 25) the family of the young protester was informed that Federico had died from a heart attack while sleeping in the jail of the police station of Via Laietana. When this was known by Federico's comrades, Barcelona was rocked by an explosion of pain. From October 27 to 30, a wave of demonstrations in protest against police brutality. On October 28, the same happened in Tarragona, followed by Lleida and Girona on the following day. In Barcelona, the marchers were blocked by Loyalists led by Adolfo Muñoz Alonso (1915-1994), an ultra right leader that, in those days, would become one of the most important leaders of the Loyalists in Catalonia. When, on October 30, a demonstration in Lleida was repeatedly attacked by loyalists armed with iron bars, bricks and bottles while the police did little to protect the demonsstrators. When the news spread, it sparked serious rioting between Nationalists and the police. When the police replied with a violent rampage through the streets of Girona, the residents sealed off their quarters with barricades to keep the police out. On the following days, the example would be followed in Barcelona, Lleida and Tarragona.

On November 5, the police entered one the nationalist quarters of Girona, Pedret, in armoured cars and tried to suppress the rioters by using CS gas, water cannons and eventually firearms when some Malraux cocktails₁ where thrown against the armoured cars. When the police returned with reinforcements, the Nationalist "defenders" opened fire against them with rifles and even submachine guns. It was the beginning of the battle of Pedret (November 6-8, 1970). Then, on the following days, the protests also took place in the Balearic islands (November 8-11) and Valencia (November 10-12). Eighteen Nationalists and nine Loyalists were shot dead and at least 532 were treated for gunshot wounds. Scores of houses and businesses were burnt out. Thousands of families were forced to flee their homes: from November 6 to December 14, 1,260 Nationalists and 6,020 Loyalist families left their homes because of the bout of violence. Schools, theatres, cinemas and even churches were used to house the refugees. By late August 1971, half of Girona and Tarragona, a great part of Lleida and several quarters of Barcelona were non-go areas for the police.

On December 20, 1971, Tierno Galván tendered his resignation and a crisis erupted, as, for two days, there was no agreement upon his succesor. Eventually, the DP and the PCE sidelined the PSOE and elected Francisco Fernández Ordóñez, from the DP (who was picked up by Suárez, who refused to drink such a poisonous drink) as the new prime minister after three days and two nights of debate in the

Cortes. Fernández Ordóñez was primer minister from December 23, 1971, to August 20, 1972. A vehement supporter of European integration, he pushed for the integration of Spain in the European Coal and Steel Community, but faced a vicious opposition not only from France, but also in the

Cortes, from both left and right parties until he dropped. He would be more succesful in his farm reform, to increase farm loans, and with a tax reform which lowered taxes for low-income groups. Budget deficits, however, would be the bane of Fernández Ordónez during his tenure.

Catalonia, of course, kept being a thorn in Spanish politics. The widespread violence forced the prime minister to send the Army to Valencia and the Ballearic Islands and to reinforce the military deployed in Catalonia. After a Loyalist gunman was shot by a Nationalit gunman in Valencia (January 2, 1972), an armored car of the Police opened fire with its heavy machine gun, killing four, included a nine year old child killed inside his house, who was hit by a stray bullet. By the time that the soldiers patrolled the streets and violence came to another temporary end, more than 600 houses had been destroyed in Catalonia, Valencia and the Ballearic Islands and almost 10,000 families had been evacuated by January 5, 1972. Casualties rose to 32 (24 Nationalists and 8 Loyalists) dead and 3,000 injured (included 650 from gunshot wounds - 360 Nationalists and 290 Loyalists).

However, Fernández Ordóñez could boast that the soldiers were welcomed and greeted in Valencia and the Ballearic islands. In Catalonia the reinforcements were simply greeted with cold distrust by the Nationalists . Meawnhile, the Interior Minister, Antonio Garrigues Díaz-Cañabate, was worried by the sorry state of the security forces in the eastern parts of Spain, which reminded him of a defeated force. However, the arrival of the army brought a temporary peace to Valencia, as it had happened in Catalonia, but not a solution. Fernández Ordóñez blamed the Catalan Army for the violence, accusing its leaders of causing the riots, but this statememt would be proved false by the internacional press. Over the following weeks, tension remained, but it looked as if the worst had passed. Then, when the prime minister ordered to reform the police forces in the East of Catalonia and to dissolve the reserve units that had been mobilized during the emergency and had proved to be not only unreliable but also prone to act withtout orders, violence returned in several Loyalists quarters in Barcelona, Tarragona, Alicante and Valencia (February 11, 1972), as the Loyalists attacked the police. It was the world upside down for the flabbergasted Fernández Ordóñez. Sixty-two people were shot dead during street violence in the loyalist areas. Fifty one were Unionist civilians and eleven were policemen. Ironically, the Spanish Army was cheered in the Nationalist areas.

Meanwhile, a deluge of weapons and heavy equipment flooded the French border in their way to the Catalan army while peace returned to the cities as the guns of the urban guerrillas felt silent.

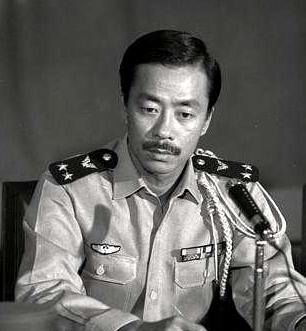

As buildings burn, Spanish soldiers patrol the streets after being deployed. This men belong to the

12th Infantry Brigade, from the Reserve force. They are armed with the British Rifle No.9 Mk1, Some units

still used the Spanish CETME and even the American Armalite AR-10.

₁ - TTL version of the

Molotov cocktail.