Background

Background

The fall of the Bonaparte dynasty after the crushing defeat suffered at the War of the Three Emperors (1916-1919) gave birth a new world, with the Russian Empire emerging victorious but fatally weakened by the war effort and the former ally of France, Austria-Hungary, teetering on the verge of collapse and only kept it place by the fears of Nicholas II to the emerging power of the newly formed German Empire, which had completely eviscerated the pro-French kingdom of Poland. Furthermore, Berlin was also closely watched by the British Empire, which had remained neutral during the conflict.

As France plunged into chaos with the proclamation of the Republic and the constant threat of a Bolshevik revolution, Spain began again to find a way to proclaim its independence and to expel the French administrators and officials that remained in the country. Before the Armistice, Napoleon IV, anxious to secure Spain, had instructed Albert-Pierre Sarraut, Governor-General of Spain since May 1917, to find suitables candidates to form a "Spanish" cabinet which would cooperate with France and to declare Spain independent of France. However, this "independence" would rest on the government's willingness to co-operate with France and accept the French military presence. From March to August 1919 Spain underwent this mirage of "independence" which was constantly undermined by Paris. The French were determined to minimize internal change in Spain that would affect their military situation and, thus, the government that was formed with Augusto González Besada as its prime minister had no power at all, as all the Spanish affairs were still in the hands of the French.

Ironically, this was an opportunity for the Spanish nationalists. Temporarily freed from French repression, Spanish revolutionaries had much greater freedom of movement. In May 1914, Salvador Seguí had formed the Liga por la Independencia de España (LIE₂ - League for the Independence of Spain), during a clandestine meeting of the Spanish Communist Party at Huesca. In 1919, as the French were content to control the large cities as their forces in Spain were constantly reduced to reinforce critical sectors of the Western Front, the LIE took advantage of the situation and used their revolutionary cells to take control of the countryside and adopted a guerrilla warfare style as the nucleus of its revolutionary strategy while carrying out propaganda activities and organizational work all over the country to prepare for the anticipated popular insurrection.

However, the LIE was not the only ones that readied themselves for the as several political parties, groups, and associations were formed throughout Spain. In Castille, because of the weak status of the communist movement, the LIE had little weight in the preparation for the insurrection; in Madrid the LIE was under the control of Francisco Largo Caballero, who proved to be too radical even for his closest allies, Indalecio Prieto and Julián Besteiro. In the north, in Navarre, a monarchist organization called Comunión Tradicionalista (CT - Traditionalist Communion), who supported the rights to the Spanish throne of Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855), the second surviving son of Carlos IV of Spain and the younger brother of the deposed Ferdinand VII. In 1919 they supported Don Carlos' great-grandson, Jaime, Duke of Madrid, born in 1870. Ironically, Jaime also claimed the French throne as Jacques I and used the style Duke of Anjou; he had also joined the Russian Imperial Army, fighting in its ranks during the Boxer Uprising (from summer 1900 till spring 1901) and the Russo-Japanese War (starting the spring of 1904, until he retired from the army in 1909₃. Traditionalist leaders opened talks with the heads of other southern nationalist groups, including the Communists, to fight for an independent Spain.

On top of all that there was the 1918 influenza: between May 1918 and April 1919 the flu killed 200,000 Spaniards and greatly contributed to the crisis of authority in the country. The French did not take effective measures to fight the epidemic and González Besada's government could do nothing without French consent. The misery and anger caused by the flu led many to take a new interest in politics, especially among the younger generation, which the LIE turned to its advantage; they conducted raids on French military hospitals and the private clinics which were exclusive of the French high class and their Spanish collaborators, the so-called afrancesados. Thus the LIE not only increased their popular support and ridiculed González Besada's cabinet for its impotency, further enhancing the popular hatred against the French and the afrancesados even if it came with a price, as the French retaliated in kind against the population, which, in turn, increased the popular anger and the support to the LIE,

Eventually, Seguí, Largo Caballero, Prieto and Besteiro were able to reach an agreement upon a common plan of action with the so-called Zaragoza Pact.. It began with the UGT, an established socialist union in Madrid and Basque Country, organizing a revolutionary general strike in August 1919, which received the support of the CNT, a Comunist union₄ operating mainly in Catalonia. The manifesto that LIE, UGT and CNT prepared for the strike began:

The fall of the Bonaparte dynasty after the crushing defeat suffered at the War of the Three Emperors (1916-1919) gave birth a new world, with the Russian Empire emerging victorious but fatally weakened by the war effort and the former ally of France, Austria-Hungary, teetering on the verge of collapse and only kept it place by the fears of Nicholas II to the emerging power of the newly formed German Empire, which had completely eviscerated the pro-French kingdom of Poland. Furthermore, Berlin was also closely watched by the British Empire, which had remained neutral during the conflict.

As France plunged into chaos with the proclamation of the Republic and the constant threat of a Bolshevik revolution, Spain began again to find a way to proclaim its independence and to expel the French administrators and officials that remained in the country. Before the Armistice, Napoleon IV, anxious to secure Spain, had instructed Albert-Pierre Sarraut, Governor-General of Spain since May 1917, to find suitables candidates to form a "Spanish" cabinet which would cooperate with France and to declare Spain independent of France. However, this "independence" would rest on the government's willingness to co-operate with France and accept the French military presence. From March to August 1919 Spain underwent this mirage of "independence" which was constantly undermined by Paris. The French were determined to minimize internal change in Spain that would affect their military situation and, thus, the government that was formed with Augusto González Besada as its prime minister had no power at all, as all the Spanish affairs were still in the hands of the French.

Ironically, this was an opportunity for the Spanish nationalists. Temporarily freed from French repression, Spanish revolutionaries had much greater freedom of movement. In May 1914, Salvador Seguí had formed the Liga por la Independencia de España (LIE₂ - League for the Independence of Spain), during a clandestine meeting of the Spanish Communist Party at Huesca. In 1919, as the French were content to control the large cities as their forces in Spain were constantly reduced to reinforce critical sectors of the Western Front, the LIE took advantage of the situation and used their revolutionary cells to take control of the countryside and adopted a guerrilla warfare style as the nucleus of its revolutionary strategy while carrying out propaganda activities and organizational work all over the country to prepare for the anticipated popular insurrection.

However, the LIE was not the only ones that readied themselves for the as several political parties, groups, and associations were formed throughout Spain. In Castille, because of the weak status of the communist movement, the LIE had little weight in the preparation for the insurrection; in Madrid the LIE was under the control of Francisco Largo Caballero, who proved to be too radical even for his closest allies, Indalecio Prieto and Julián Besteiro. In the north, in Navarre, a monarchist organization called Comunión Tradicionalista (CT - Traditionalist Communion), who supported the rights to the Spanish throne of Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855), the second surviving son of Carlos IV of Spain and the younger brother of the deposed Ferdinand VII. In 1919 they supported Don Carlos' great-grandson, Jaime, Duke of Madrid, born in 1870. Ironically, Jaime also claimed the French throne as Jacques I and used the style Duke of Anjou; he had also joined the Russian Imperial Army, fighting in its ranks during the Boxer Uprising (from summer 1900 till spring 1901) and the Russo-Japanese War (starting the spring of 1904, until he retired from the army in 1909₃. Traditionalist leaders opened talks with the heads of other southern nationalist groups, including the Communists, to fight for an independent Spain.

On top of all that there was the 1918 influenza: between May 1918 and April 1919 the flu killed 200,000 Spaniards and greatly contributed to the crisis of authority in the country. The French did not take effective measures to fight the epidemic and González Besada's government could do nothing without French consent. The misery and anger caused by the flu led many to take a new interest in politics, especially among the younger generation, which the LIE turned to its advantage; they conducted raids on French military hospitals and the private clinics which were exclusive of the French high class and their Spanish collaborators, the so-called afrancesados. Thus the LIE not only increased their popular support and ridiculed González Besada's cabinet for its impotency, further enhancing the popular hatred against the French and the afrancesados even if it came with a price, as the French retaliated in kind against the population, which, in turn, increased the popular anger and the support to the LIE,

Eventually, Seguí, Largo Caballero, Prieto and Besteiro were able to reach an agreement upon a common plan of action with the so-called Zaragoza Pact.. It began with the UGT, an established socialist union in Madrid and Basque Country, organizing a revolutionary general strike in August 1919, which received the support of the CNT, a Comunist union₄ operating mainly in Catalonia. The manifesto that LIE, UGT and CNT prepared for the strike began:

Con el fin de cambiar a las clases dominantes a aquellos cambios fundamentales del sistema que garanticen al pueblo el mínimo de condiciones decorosas de vida y de desarrollo de sus actividades emancipadoras, se impone que el proletariado español emplee la huelga general, sin plazo definido de terminación, como el arma más poderosa que posee para reivindicar sus derechos.₅

Negotiations began with the bourgeois parties, namely Alejandro Lerroux’s republicans, as the Conservative Party was considered to be too afrancesado and the Liberals too unreliable. They discussed the formation of a provisional government, with the moderate Melquiades Álvarez as president and the Socialist Pablo Iglesias as minister of labor.

Then, on August 3, 1919, Phillipe Petain unexpectedly arrived to Madrid.

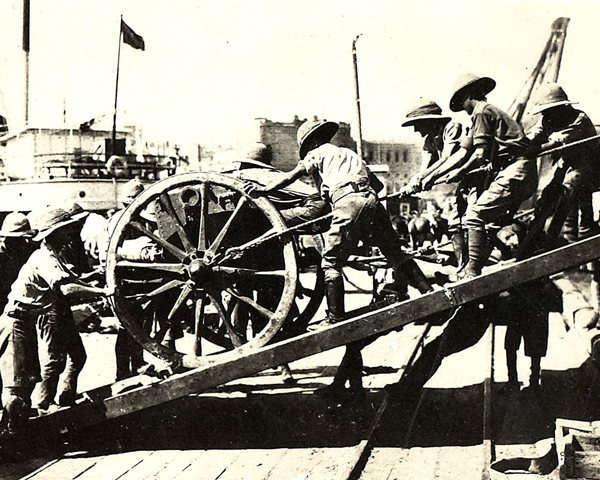

Trains stuck in the railway station of the mining area of Riotinto

due to the sabotage carried out by the LIE guerrillas.

₁ - IOTL Seguí was a Catalan anarcho-syndicalist. ITTL, Communism is stronger than IOTL.

₂ -Acronyms can be funny from time to time.

₃ -Sometimes real history is even stranger than any TL of this forum.

₄ -IOTL, CNT was an anarchist union, but ITTL it's changed into a Communist one for the sake of the history.

₅ -"With the goal of holding the ruling classes to those fundamental changes of the system that guarantee the public, at minimum, decent living conditions and the development of their self-emancipation, the proletariat of Spain must employ a general strike, with no specified end date, as the strongest weapon that it possesses in reclaiming its rights."

Last edited:

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/larazon/MDEANCANYVAKTE457JJQPLJIYU.png)