You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Silver Knight, a Lithuania Timeline

- Thread starter Augenis

- Start date

Thank you for an amazing timeline Augenis. I haven't yet seen anything like it, in either scope or execution. Truly a wonderful work of fiction.

I would also like to thank you for allowing me and, of course, other readers to create our own entries and stories in this amazing world you have created.

I would also like to thank you for allowing me and, of course, other readers to create our own entries and stories in this amazing world you have created.

Maybe yes, maybe no. I have a few ideas on what I might project do in the future, but it depends on real life.Wow amazing TL, any plans for a future project?

And I am still theoretically running that American Bronstein TL, even if I have been ignoring it.

Once ruled by Nazbols, now ruled by a Trump/Putin. India's an odd candidate for shaking up the literally-neocolonialist world order, but its better than nothing...

In all seriousness, I like how this ended. You've consistently avoided utopianism in this TL, even to the point of making the various Lithuanian governments a little villainous in their attitudes to minorities. Glad to see that trait enduring all the way to the last update, and leaving us with a world that is very difficult to figure out. Not that a couple of us won't try in guest posts...

Speaking of guest posts, I second @Sigismund Augustus's expression of thanks. The work I've done here is some of the most extensive I've done on AH.com and I've loved every minute of it. It's taught me a lot of research and time-management skills that I didn't have on previous attempts (a previous TL attempt of mine went dead after the fourth post) and I look to make use of them in the future. (As for posts on this TL, I assume we're still asking for your permission before posting them?)

And you should link the Bronstein TL in your signature. It's honestly a great read so far, and needs more exposure.

In all seriousness, I like how this ended. You've consistently avoided utopianism in this TL, even to the point of making the various Lithuanian governments a little villainous in their attitudes to minorities. Glad to see that trait enduring all the way to the last update, and leaving us with a world that is very difficult to figure out. Not that a couple of us won't try in guest posts...

Speaking of guest posts, I second @Sigismund Augustus's expression of thanks. The work I've done here is some of the most extensive I've done on AH.com and I've loved every minute of it. It's taught me a lot of research and time-management skills that I didn't have on previous attempts (a previous TL attempt of mine went dead after the fourth post) and I look to make use of them in the future. (As for posts on this TL, I assume we're still asking for your permission before posting them?)

And you should link the Bronstein TL in your signature. It's honestly a great read so far, and needs more exposure.

It's now linked down there (I didn't even know you read it, tooOnce ruled by Nazbols, now ruled by a Trump/Putin. India's an odd candidate for shaking up the literally-neocolonialist world order, but its better than nothing...

In all seriousness, I like how this ended. You've consistently avoided utopianism in this TL, even to the point of making the various Lithuanian governments a little villainous in their attitudes to minorities. Glad to see that trait enduring all the way to the last update, and leaving us with a world that is very difficult to figure out. Not that a couple of us won't try in guest posts...

Speaking of guest posts, I second @Sigismund Augustus's expression of thanks. The work I've done here is some of the most extensive I've done on AH.com and I've loved every minute of it. It's taught me a lot of research and time-management skills that I didn't have on previous attempts (a previous TL attempt of mine went dead after the fourth post) and I look to make use of them in the future. (As for posts on this TL, I assume we're still asking for your permission before posting them?)

And you should link the Bronstein TL in your signature. It's honestly a great read so far, and needs more exposure.

My initial imagining of the ending of this timeline, originally thought up somewhere around... the 18th century in this TL, was actually fairly utopian. Unitarianism and Revivalism both destroyed and disgraced, both China and the West as democracies, everything's sunshine and flowers. The greyness started stacking up as I went. The different approach to colonialism in Africa led to the continent never breaking free from colonial rule, and having India as revanchist rather than complacent was an opportunity too good to pass up. The reader updates adding nuance to the world had a big impact, too.

And I'm glad to have helped you all, and, in fact, I have to share that thanks as well! Quite often, your updates would be more researched and interesting than what I think up of.

It's nice to see that the TL does not end with your last post. It has been an amazing read; and the reader updates do not make your portion any less outstanding. They only make it better by illustrating what you alluded to.

So, can we see a "Where are they now" epilogue on the fate of certain characters of the Great Asian War-era?

If you want to know about the fate of someone, you can ask here, I'm all ears.So, can we see a "Where are they now" epilogue on the fate of certain characters of the Great Asian War-era?

What became of Yang anyways? Did she ever become Chancellor?If you want to know about the fate of someone, you can ask here, I'm all ears.

Most likely yes, sometime in the early to late 1990s. It was a fairly calm period in the world at the time, what with India still more or less a complacent partner, technology innovating every day and climate change still appearing as a distant threat, so she would be viewed positively by the Chinese after her term ended.What became of Yang anyways? Did she ever become Chancellor?

Actually, I'm not all that sure. I haven't thought much about post-war Virginia besides having it be dominated by Inca economic interests, so there is a lot of leeway there. The VPA might become more influential in the 1990s as a reaction to this economic domination, so having Margaret Tyrell rise to the top is definitely a possibility (although I would find it very unlikely for a British colony to elect a woman leader so soon after independence; even the post-colonial states have a lot of remaining Catholic conservatism, I would imagine).What about the characters I created in my Virginia guest update?

Since it's your characters, what did you imagine their future as when you write them?

God of Justice

This is not an epilogue post, just a guest post that I was holding on to. Every event featured here happens before the end of the 1960s, but it does lay the groundwork for some of my ideas on what a post-GAW world might look like, making it a... pre-epilogue? Anyways, it's got plenty of fun reminders of what TTL's world looked like a century or two ago. What halcyon days...

God of Justice: The Foundations of Modern Serbia

Nationalist historians will proudly insist that the “titular ethnicities” of each Balkan state remained the majority of the population in their respective regions throughout the entirety of Ottoman rule, but their focus on raw percentages makes them unable to see šumu od drveta (“the forest for the trees,” as the regional proverb goes). While the people of Ottoman Rumeli (“the country of the Romans”) were diverse in language and culture, the more important thing to remember is the degree of their interconnectedness. Despite the stereotype of all Balkan Muslims being beys or ayans who lorded it over servile masses of Christian peasants, many Muslims were active and productive participants in agriculture, trade, culture, and urban life, and existed at all rungs of the socioeconomic ladder. The region’s Christians were more likely to identify by church affiliation rather than any concept of “ethnic identity”. Amidst them all, the Jews lived lives of quiet prosperity centered on great cultural hubs like Salonica, and the Romani lived a myriad lifestyles (though that of the nomadic traveler is perhaps the best-known to outsiders). The emergence of majority-Christian, territorially-bound South Slavic nation-states from the corpse of Rumeli was therefore never an inevitability or even particularly easy. The birth of Serbia in particular was the product of specific circumstances, which included the building of schools and hospitals as well as the displacement and murder of hundreds of thousands of people.

In 1799, Buda’s consul in Sarajevo had forwarded copies of the edicts of Sultan Harun I, which provided for sweeping administrative reforms in the Balkan provinces. The refugees who trickled into southern Hungary and eastern Croatia from the 1810s onward told a different story. The reforms of the army, meant to chip away at the power of the Janissary corps, were never implemented by the Bosnian administration. The coalition of soldiers and landowners who governed the province had no interest in abolishing tax-farming or lowering land rents— instead, they forced the reaya (the tax-paying class of peasants) to cough up increasing amounts of wealth and participate in forced-labour projects. Rather than the new rights and protections promised by the Sultan, Christians faced only the bleakest of futures as the Janissaries ran amok, seizing land and tearing to bits the very security and peace they were supposed to protect. In 1827, they even assassinated Hüsrev Pasha, the governor of Bosnia, for attempting to place checks on their soldiers’ power.

Sultan Harun could not protest overmuch at this— a conspiracy of the Janissaries in Thrace removed him from office in 1828. His absent-minded younger brother ruled thereafter as Abdülaziz I, and did nothing to rein in the actors who lurked behind his throne. The opponents of the Bosnian provincial oligarchy, aware that the Sultan was no longer sympathetic to their cause, considered increasingly drastic options. By 1833, the public anger in the Serb-majority villages surrounding Banja Luka had engulfed northeastern Bosnia. Suffering from the savage retaliations of the Bosnian provincial forces, which had the full backing of Constantinople, the directors of the revolt (a motley collection of Orthodox bishops, secular Serbian notables, and Muslim notables with fond memories of Hüsrev Pasha) sent a messenger to Buda.

Ladislaus II, King of Visegrad from 1824 to 1848.

The monarchs of Visegrad after the German Revolutionary Wars were not “Luxemburgs” in the traditional sense. The main line of the Luxemburg dynasty ended with Sigismund II, who capped off two years of wholesale military and political collapse in the Three Kingdoms by dying without heirs in his provisional capital at Lublin. The French and Lithuanian delegates at the Paris Congress therefore selected Franciszek I, a cousin of Sigismund who headed the Luxemburg-Łańcut cadet branch (headquartered in Łańcut Castle and adjoining estates in Poland) of the ruling dynasty, as the new king.

Franciszek ruled for 13 years, but they were uneasy ones— he never became fluent in Hungarian, and accordingly never escaped the Buda elites’ perception of him as a Polish immigrant. Upon his death in 1789, the task of rebuilding the kingdom’s political infrastructure was taken up by his son Matthias IV. The transfer of power to King Matthias “the Mad” V in 1815, however, was an enormous setback for the House of Luxemburg-Łańcut. While the King shut himself in his palace and refused to touch anyone for fear that he would turn to glass and shatter, the Convention of Three Nations steadily accrued power— its Chairman, Count Zsigmond Tisza, became the de facto head of government. King Ladislaus II, son and successor of the Mad King, was acutely aware of the crisis that his House faced. On the one hand, the institution of monarchy was the foundation of the nation— the institutions which tied Hungary, Bohemia, and Poland together all derived their legitimacy from the King. However, the popularity of the monarchy had declined as a result of the elder Matthias’s authoritarian tendencies and the younger Matthias’s incompetence. To ensure that the people— and especially the growing middle classes— felt obligated to preserve the status quo, the monarchy (and, by extension, the broader Visegradian system) needed some kind of victory that would prove their ability to set and achieve goals, adapt to change, and resist foreign aggression.

Events in the Ottoman Empire paved the path to that victory. Visegrad’s literate (and illiterate) public were aghast at the newspapers' lurid descriptions of the “Bosnian Terrors” perpetrated by the Janissaries during the summer of 1833. The different factions of the government lost no time in responding to the popular sentiment that Visegrad, by virtue of its strength and advanced political culture, was duty-bound to stop such atrocities from happening in its own backyard. In a joint session of the royal court and the Convention, royalist politicians and a collection of major political parties produced the December Charter, in which the Convention pledged political and financial support for any of King Ladislaus’s initiatives with regard to the Bosnian question. Once the crisis was resolved, the King would consent to the immediate formation of a Constitutional Congress that formally apportioned powers between King and Convention and ended the see-saw shifts of power that had occurred during the reigns of the two Matthiases. With this support, a special committee chaired by the King sent an ultimatum to Sultan Abdülaziz, demanding that he rein in his military and grant Bosnia financial and political autonomy. The Sultan’s refusal of that ultimatum triggered the Bosnian War of 1834. All that really needs to known about the war is that Visegrad had, since the time of Franciszek I, committed to memory the lessons taught by the Revolutionary German Army and stayed abreast of military developments in the years since. The Ottomans, who had not yet suffered any significant reversals in Europe, saw little need to reform their military. Old thinking and old weapons clashed with newer variants of both, and the latter won. Three months after the declaration of war, Constantinople consented to the Visegradian annexation of Bosnia.

Militarily, the integration of Bosnia proved little trouble— many of the leading members of the local Janissary elite were dead, and the power of the survivors had been broken by the war. Politically, however, it threatened to derail the Constitutional Congress of June 1834. Since its conquest, Bosnia had been governed as a military district, but how would its status change after the introduction of civilian rule? Would it be made into a fourth Visegradian kingdom? Would it become a province of Hungary, thus making the senior member of the federation even more powerful? What precedent would this set for future annexations of territory? In the end, the Congressmen determined that Bosnia should, following medieval precedent, become a Banate of Hungary. Like the Banate of Croatia, Bosnia would have its own local sabor (“assembly”), which would rule in coordination with a ban (“governor”) appointed by the Hungarian National Diet in Pest. The status of Pest as a “Hungarian” capital distinct from the federal capital of Buda was also confirmed by the Constitutional Congress, whose Bohemian and Polish delegates successfully pushed for national diets in their own kingdoms. The most significant effect of the Congress on a national scale was the transfer of the King’s powers to propose new legislation, declare war, and conclude treaties to the Convention. Agreeing to these conditions, Ladislaus believed, was the only way to ensure the long-term popularity (and thus survival) of the monarchy. In a sense, he was right— the goodwill which the House of Luxemburg-Łańcut built up during the 1800s let it outlive Visegrad itself, and become the ruling house of modern Hungary.

With the Convention over and normalcy restored, civilians (though not necessarily natives) gradually assumed responsibility for Bosnia’s day-to-day administration. The third Ban of Bosnia, however, was not a Hungarian like his predecessors. Rodoljub Vulović, an Orthodox noble from Trebinje, had first become known to the Visegradians through his active military cooperation with the invading armies of 1834. Appointed as Ban in 1846, Vulović carefully balanced tradition and change in Bosnia for the next twelve years. The Muslims of central and western Bosnia were assured that Visegrad would henceforth protect them from forceful conversion to Christianity and from violence against their persons and private property. However, the traditional feudal rights of the landowners were, as in the rest of Visegrad, abolished. The nobles of Bosnia were now legally indistinct from landowners of common origins, and like commoners they now depended on their entrepreneurship— their ability to extract produce from their lands and bring it to market— to retain or rebuild their wealth. Some failed at playing this game, some succeeded, and some chose not to play at all. Instead, they sold off their lands and invested in the urban infrastructural, financial, and educational projects commissioned by the Visegradian state and its contractors.

Vulović’s main gift to the Serbs, however, was ecclesiastical reform. The Ottomans had abolished the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć in the 1750s. For the next century, the various metropolitanates and eparchies of the Serbian lands were subordinate to the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, which was dominated by Greeks and frequently collaborated with the Ottoman government. When the Serbs were loyal to the Ottoman government, this did not pose much of an issue— but as the Orthodox faithful of Bosnia became rebels, refugees and then Visegradian citizens, the question of where to turn for moral and cultural guidance became quite pressing. With this in mind, Vulović recommended to Buda that Dragan Nastić, the popular Metropolitan of Zvornik, be rewarded for his efforts to encourage local support for Visegradian rule and laws. On January 7, 1850, Ladislaus’s successor Joseph II approved the election of Dodik as the “Patriarch of Zvornik” by an assembly of Bosnian Orthodox bishops hosted in the Ban’s Court in Sarajevo. The new church proved influential in the creation of an ideal of Serbian nationhood on both sides of the Visegradian-Ottoman border.

During their swift advance through Bosnia and their suppression of the brief resistance movement that followed, the Visegradians killed or imprisoned thousands of landless soldiers pressed into service by their traditional Janissary commanders. Those commanders were dispossessed of their followers and their property, and forced to leave Bosnia at gunpoint. The humiliation of Rumeli’s power-brokers did not end there— the Wallachian War of 1834 saw Lithuania gobble up the majority-Romanian lands north of the Danube. If the Ottomans hadn’t held back the Lithuanians at the riverine fortress city of Nikopol, the Lithuanians might even have advanced into Bulgaria. Although Nikopol was a victory for the Ottomans, around 25,000 Ottomans were wounded and 15,000 died that day. Among that number were the famed Janissary commanders Nuri Cebeci and Gazi Kapıkulu, who had carved out nearly-independent personal fiefdoms in eastern Bulgaria and Thrace, respectively. The final hammer-blow came not from the north, but from the south. The First Greek War of Independence nearly drove the Ottomans from the Balkans. While the klephts and rebels came down from the mountains and seized the towns and valleys, the Patriarch of Constantinople refused to condemn the uprising. Demoralized by the setbacks against Visegrad and Lithuania, the Ottoman armies lost crucial battles at Nafplio and Piraeus over the course of 1835. If the Greeks expected help from European governments, however, they were sorely mistaken. As splits within the Greek rebel leadership slowly widened over the course of 1836, the Ottomans regained ground. Still, the war lasted until 1840. By its end, most of the Muslim population in the formerly rebel-held zones (around 20,000 in total) had been killed or expelled to other provinces within the empire. Most of those who were expelled had no intention of returning.

In this chaotic time, Sultan Abdülaziz may, if nothing else, be praised for his loyalty to those who put him on his throne. As the political and military bosses of Rumeli trekked or sailed to Constantinople, the Sultan ignored their failures and gave them refuge, and permitted them to rebuild their shattered military corps. Rather than attempting any form of radical or even moderate change, the Sultan and his clique seem to have simply not considered enacting any reforms, fearing (justifiably) that reforming the empire’s entrenched institutions would simply create more enemies for the monarchy and erode its already-flagging authority. By committing to this timid course of action, however, Abdülaziz made the very enemies he’d sought to avoid. Sultan Harun had died in exile in Baghdad in 1836, but his ghost seemed to haunt the Empire still.

The Asakir-i Emniyet (“Soldiers of Security”), a force of military police that kept order in the bustling capital, was originally created in Harun’s time. Drawn from the Janissary corps and trained according to European models by imported officers well-versed in post-Schwarzburg technology and strategy, the Emniyet had been intended as the core of a new army that would gradually assimilate the functions and members of the Janissaries. It was this provocation more than any other which compelled the Janissaries to install Abdülaziz in the first place, but the new Sultan did not abolish the Emniyet. Instead, he restricted its jurisdiction to Constantinople alone, with the intention of keeping it around as a police force. The organization’s mission to keep public order, however, was imperiled by the stream of incoming Janissaries. Unruly and armed gangs of them began roaming the streets almost as soon as they had settled down, looking for new opportunities and old scores to settle. The ulema, or Muslim intelligentsia, of the city also disliked the corruption, arrogance, and thinly veiled impiety of the new arrivals. In this, they were joined by the civilian population, whose sojourns throughout the city had become much more dangerous since the arrival of the eşkıyalar (“bandits, thugs”).

At first, the political clique who had held Abdülaziz’s hand throughout his reign didn’t think much of his son Yunus, and approved the boy’s status as heir apparent. Almost immediately after succeeding his father in 1846, however, Yunus I proved to be a fatal threat. In imperial rescripts and letters to reformist governors in Anatolia and western Persia, Yunus wrote of the need to “act calmly and with firm purpose for the good of the Sublime State” and not fall prey to “those wolves who would convince us that they are tame dogs.” Within Constantinople, Yunus sought to engineer conflicts with the elite of his father’s time wherever possible by snubbing Janissaries for ministerial appointments and refusing to silence civilian critics of their activities in the city. Events came to a head when the respected and elderly cleric Ahmet Resneli was found dead in his home in the Kasımpaşa quarter in July 1849, killed by an unknown assailant. After going through the motions of investigation, the Emniyet found a witness willing to point the finger at Küçük Ali, a former Grand Vizier of the Empire during the middle of Abdülaziz’s reign who had been criticized by Resneli for refusing to give sadaqah, or voluntary charity, to civilian refugees from the wars in the Balkans. Yunus promptly and publicly denounced Küçük Ali and called for him to be tried in court for his crimes. Incensed by this brazen assault on one of their own, the Janissaries attempted to overthrow Yunus as they had overthrown his uncle Harun— and found that they couldn’t. They had no significant support from any sector of the city’s population, and faced significant opposition from the Emniyet and Yunus’s personal guard. The imperial bureaucracy had undergone a generational shift, and now consisted of large numbers of officials who had grown up during the disasters of the 1830s and wondered if things could have gone differently if Harun’s reforms had been allowed to proceed. With all avenues to power closed off and all sympathy burned away by their treasonous attempt at revolt, the would-be putschists surrendered over the course of August, or were smoked out of their hiding-holes in September. The finishing touch came with the promulgation of the Fermân-ı Yıldız(“Edict of the Star,” named in reference to the imperial gardens of Yıldız Palace) in January 1850, which formally abolished the Janissary corps and provided for the establishment of a new and modern army and imperial guard.

The subsequent “Star Period” (Yıldız Devri) gave the empire new life. To fill the vacuum created by the elimination of the Janissaries as arbiters of political and military power in the provinces, the Sultan and his reformist Grand Vizier Cemal Pasha spearheaded a reorganization of provincial administration. The 1854 “Law of the Provinces” created new administrative councils in every province, which would rule in coordination with the state-appointed governor. The composition of the councils was based on a partially electoral process— those portions of the population who had the franchise were presented with a list of candidates vetted by Istanbul, and then allowed to strike off names from the list. Prerequisites for voting included being male, being over 30, and not being a citizen in a foreign country or an employee of a foreign government. The partial regularization of provincial administration and accompanying checks on the previously unrestrained power of local elites were important components of the Ottoman pursuit of the rule of law. Under the theoretical leadership of Ibrahim Efendi, Grand Mufti of the Empire, a team of bureaucrats and legal experts acting in a mostly autonomous manner compiled the secular and Islamic laws of the country into a uniform code of civil laws known simply as the Mecelle (“legal code”). While the more rebellious Janissary corps had been dissolved entirely, with their commanders arrested or killed, loyalist corps and soldiers formed the backbone of the reformed Ottoman Army, which was meant to unify the defensive and offensive capabilities of the nation. A number of its officers consisted of former leaders of the Emniyet (which subsequently lost its military functions and evolved into a civil police force) and foreigners employed by the Porte. A number of these foreigners were French, and over the course of the late 50s the Ottomans struck up a fruitful rapport with Paris. Though moves to open up Ottoman markets to French goods were unpopular in the short term, Sultan Yunus’s government gained vital military and economic assistance as well as an ally that could keep Visegrad and Lithuania at bay. French academics also helped set up the Encumen-i Daniş (Academy of Sciences) in Istanbul, whose primary aim was to train teachers and create textbooks that could be used in future schools and universities.

Despite his active support for reform efforts, Yunus was no progressive. In 1857, a dispute arose between the Sultan and Cemal Pasha over the purchase of arms from Visegrad. The Sultan believed that Visegrad was overcharging the Ottomans for products which could be bought more cheaply from France. Meanwhile, Cemal Pasha argued that the Ottomans could afford to spend the money, and that establishing strong relations with multiple European governments was diplomatically more sensible than relying solely on France for assistance. The dispute seems to have contributed to a breakdown in relations between the two men, and a year later Yunus dismissed Cemal Pasha from the post of Grand Vizier and appointed Rıza Reşid, a Persian protege of Cemal’s who had written an editorial in praise of the Paris System in a Constantinople newspaper some years prior. Rather than allowing political disputes to play out in an democratic or remotely open arena, the Sultan seemed intent on resolving them behind closed doors and through his own increasingly absolute power. This approach to conflict resolution soon impacted the mindset of the combatants. Though the Cemiyet-i İslahat (“Committee for Reform”) set up by Fuad Keçeci, another protege of Cemal Pasha and rival of Rıza Reşid, seemed to be a political party, it was really just a patronage machine which connected the younger sons of provincial notables to posts in the state bureaucracy, and low-ranking bureaucrats to more important positions. Once in place, the members of the Cemiyet were to secure the favor of the sultan and his associates and engineer the demotion or expulsion of Reşid’s partisans. “Party politics” was less concerned with resolving differences of opinion between clashing agendas (Keçeci and Reşid agreed on most matters of basic policy) than with struggles for paramount leadership, in which one party attempted to turn the sultan against the other. In the process, both parties recognized the legitimacy of Sultan Yunus’s considerable power. Not all political factions, however, adopted this strategy. While Keçeci and Reşid fought things out in full view of the state, other organizations adopted a more secretive existence, quietly gaining followers in the military and bureaucracy.

Yunus’s son and successor Harun II, who acceded to the throne in 1860, seemed intent on outdoing his father in reformism and absolutism. Within two years of taking office, he had revised the imperial budget to transfer massive sums of money from the military to the secular educational system. However, Harun II also made an end of widespread hopes for a democratic “Ottoman Convention” by having the theorist and philosopher Vartan Melkonian, who coined the phrase “Ottoman Convention” while teaching political science at Damascus University, exiled to the Persian Dasht-e Kavir. Over the late 1860s and early 70s, Harun II made sweeping domestic and foreign policy proposals and appointed to state ministries anyone talented enough to make them a reality. Worried about France’s initiatives of colonial infiltration in the Indian Ocean (preparations for the annexations of the Khmer kingdom and Ethiopia were well underway by this time) and immensely skeptical of Paris’s stated motives in regard to its Ottoman “partner,” Harun II and his Ministers of Development and Foreign Affairs consistently snubbed the French by refusing to meet their diplomats or handing contracts for railroads to rivals like Visegrad or even South Germania. The timing of this breakdown in relations, however, was quite inopportune. Colonial competition between the European powers was heating up in Africa, and every participant knew that if a choice territory was not secured immediately it might potentially be gobbled up by rivals. Jean-Isidore Harispe, then the Director of France, had been swept into power by a nationalist coalition of parties who felt that France’s longstanding preoccupation with maintaining the Paris System held it back from achieving its destiny as a world-spanning “empire of liberty.” For such a man, every country in the world was either with France or against it— and since Harun II had made his stance so clear, he must therefore suffer the consequences.

Despite declaring their respect for Ottoman borders in the 1871 Conference of Rome, the French secretly contacted Şevket Pasha, the governor of Egypt. Şevket was a younger brother of Harun II who had been tossed out of Constantinople for criticizing the Sultan’s decision to defund the army. During his “exile,” however, Şevket remained busy— he established partnerships with those generals and officers who had been inspired by his courageous stand on behalf of the military, and with prominent power-brokers like the Egyptian-Circassian Baghana family (which is still referred to in modern Egypt as the “family of pashas,” for the sheer number of high-ranking officials it produced). On the advice of Hugo Jaures, the French consul in Cairo, Şevket steadily antagonized his brother by independently hiring French military experts and taking out loans from Dutch banks without consulting with imperial officials. When Harun II moved to arrest him, Şevket declared himself to be the true Sultan of the Empire. His short but successful war against Harun ended with the conquest of Palestine in 1877, after which the French urged their Egyptian ally to stop fighting and seek peace lest other powers intervene on the side of Constantinople. The French-brokered Conference of Damascus left Şevket within theoretical Ottoman sovereignty as the Yardımcı Padişah (“helper-sultan, vice-sultan”) of Egypt and Palestine, but it was quite clear to all that Egypt was now an entity distinct from the Ottoman Empire (a guarded border ran between the Ottoman and Egyptian possessions in the Levant) and closely affiliated with France, which took possession of the Isthmus of Suez. Not until after the Great European War did the dynasty established by Shawkat al-Awwal (“Şevket the First,” in Arabic) achieve recognition of its independence from the defunct Ottoman Empire and formally renegotiate its quasi-protectorate status within the French empire on the basis of equal partnership between sovereign states [1].

The Cairo Affair of 1875 was the beginning of the end for the Yıldız Devri. Most of the French advisers in the Ottoman Army had been expelled from the Empire over the course of the war against Şevket, and native officers were given more responsibility over their own units. This did not, however, engender any feelings of warmth toward Harun II. Not since the 1830s had the Ottomans faced so terrible a defeat, and the army blamed the pernicious influence of the sultan. He had, after all, intervened numerous times during the war effort and made military decisions against the better judgement of the experts in that particular field. Furthermore, his policy of permitting the existence of factions in the officer corps and playing them off each other in the style of his father Yunus had backfired tremendously. The “Egyptian faction” of the officer corps, composed mostly of the younger sons of old Mamluk families and ambitious new-money Arabs, had developed a distinct identity in the 1860s and defected along with their subordinates to Şevket’s side when war broke out. Though these defectors spoke in their letters to Harun of a sincere wish to avoid “taking up arms against our beloved and sacred home,” most of them were also motivated by the need to prevent the confiscation of their property in Egypt by demonstrating loyalty to the new masters of that country. Those officers who remained loyal to Constantinople felt that the empire was too disunited, and that its people needed to be given a stake in its governance.

On 26 November 1878, a military coup organized by the shadowy Tahrik-i İnkılap (“Revolutionary Movement”) forced Harun II to publicly promise an Ottoman constitution. Amid widespread public enthusiasm that was fanned by the Ottoman press (which no longer had to face the censorship and restrictions that Yunus and Harun placed on it), the various provincial administrative councils elected delegates to an Ottoman Convention, which committed itself to drafting the new constitution. The resulting document drew heavily from the ideas of Vartan Melkonian in mandating that the members of the lower house of the Convention be chosen by indirect elections. Voters the in provinces would elect a college of electors, who then elected the delegates from that province to the Convention. The qualifications for being a delegate were the same as the requirements for being a voter in the provincial elections, but with the added requirement that every delegate be able to fluently speak and write Turkish (which would be the official language of the Convention’s proceedings). The number of electors and deputies from each province would be based on its percentage of the empire’s population— to the disappointment of minority leaders, no religious or ethnic group would be entitled to a quota of deputies. Melkonian’s plans, however, also included a theoretical “upper house” of the Convention, whose members would be appointed by the sultan. When asked to nominate his delegates, however, Harun stated that he did not recognize the legitimacy of the Convention and abdicated the next day in favor of his politically unambitious son Murad VI. The Convention accordingly remained a unicameral body, and the party which occupied a majority of its seats reserved the right to nominate the Grand Vizier.

For the first years of its existence, the Convention appeared to be the most effective and democratic body of governance the Ottomans had ever known. Catering to the public’s appetite for political liberalization and economic prosperity, the Convention pushed through economic deregulation, imported industrial machinery from France as a way of signaling Constantinople’s willingness to return to the productive friendship of the early Star Period, and made further efforts to reform provincial government and protect minorities from institutional injustice. Over the late 1880s, however, the Convention lost its luster and its effectiveness. By this time, the two main political parties were the Tahrik-i İnkılap, headed by Grand Vizier and former General Esad Seyhan, and the Cemiyet-i İslahat, headed by an aging Fuad Keçeci. Both parties were what could be considered “vested interests,” and had both grown used to controlling the state through means legal and illegal. As the competition for seats in the Convention grew more intense, the Tahrik accused the Cemiyet of reactionary obstructionism while the Cemiyet stirred up conservative sentiment by insinuating that the secularists of the Tahrik, having humbled the sultan, would soon abolish the Caliphate itself. In the meantime, anti-Tahrik factions in the army and amid the ministers who ran the state machinery gradually withdrew their support from the Convention. In 1893, Murad VI died, and his elder son Abdülmecid III acceded to the throne.

In 1895, the new Sultan moved to nominate members to the defunct upper house of the Convention. The Convention’s leaders refused, claiming that Harun II and Murad had both conceded to the upper house’s permanent non-existence. In response, Abdülmecid ordered the dissolution the Convention, and his brother Mehmed (who had earlier been promoted to head of the Muhaberat, the Ottoman internal security service created by Harun) dealt with any public figures who complained overmuch at this. Thereafter, the two brothers presided over the “Post-Convention Era,” in which the Ottoman state reclaimed all the high-handedness of the Star Period’s government and none of its successes. The complex process by which Abdülmecid and Mehmed (better known as Mehmed V) led the Ottoman Empire into its final and fatal disaster is explained better in other publications which make it their focus. Accordingly, it will not be covered in further detail here.

Building destroyed by bomb blast (Belgrade, 1899).

With the defeats of the 1830s, Belgrade was left as the northernmost city in the Ottoman Empire. Its military role remained largely the same as before— it was the largest of the Ottoman fortresses on the Danube, a shield which protected Macedonia, Albania, and Epirus— but as the imperial elite struggled to come to terms with the extent of their humiliation, Belgrade assumed a political and cultural significance. It was Belgrad-ı Müntasır (“Belgrade the Victorious”), the site at which the Ottoman defenders barely managed to prevent Visegrad from overrunning the lands east and south of Bosnia. It was Belgrad-ı Zaruret (“Belgrade the Indispensable”), without which the Ottoman presence in Europe, and perhaps the empire itself, would be untenable. Though the betrayal of the Greeks convinced some members of Abdülaziz’s clique that the Balkan Christians deserved to be met only with fire and sword, the accession of Sultan Yunus let cooler heads prevail. Recognizing the demands of the Serb population for an institution that would protect their interests and serve as an intermediary between them and the Sultan, Yunus’s government, with the approval of the Patriarch of Constantinople, restored the Serb Patriarchate and placed its seat in Belgrade. The re-emergence of a Serbian church, in which all levels of the hierarchy spoke the language of the common people, facilitated a cultural revival. Rather than competing with the Patriarchate of Zvornik, the Ottoman Serbian Church undertook exchanges of religious texts, icons, and experts. The resulting sense of kinship between Slavs on both sides of the border proved impactful in the long term.

Other era-defining changes included the regularization of provincial administration, codification of law, and the creation of new schools and new local police forces based on Constantinople’s Emniyet. The reforms limited the ability of local notables to openly declare war on each other, and thereby eliminated the need for mobs or bandits to take public security in their own hands. Amid this climate of relative security and prosperity, the Serbian professional class emerged. The sons of artisans and smallholders, educated in the schools run by the churches, attended the developing institutions of higher learning in the imperial capital and then returned home, where their professional skills were in high demand. During the Convention Era, the discussion clubs and salons run by these professionals and their associates became Serbia’s first modern political parties, and participated in elections for the provincial assemblies. Lacking any real presence outside of the Serb-majority provinces, these parties were usually a very small minority within the National Convention. Convention members belonging to them typically caucused with the Tahrik against the Cemiyet.

Despite these changes, however, Serbian society— as in the rest of Rumeli— retained strong feudal characteristics which perpetuated the power of a small, traditionally landowning elite. The great mass of the region’s inhabitants— Christian and Muslim— lived in the countryside. The influence of large landowners, village headmen, and other rural elites allowed them to easily secure a place in the provincial councils created during Yunus’s reign. Local notables also dominated the provincial electoral colleges, and opportunistically elected only members of whichever party was strongest within the Convention at the time. By consistently allying themselves with the stronger party, the elites hoped to continue functioning as intermediaries between their people and an approving national government. However, this often came at the expense of native Serbian political parties which sought to challenge the status quo. The failure of enlightened absolutism and democratic rule to address social stratification and entrenched privilege was noted by the growing numbers of politically conscious Serb commoners, but even during the nadir of the Convention era many still believed in the viability of the Ottoman system and Serbia’s place in it. After all, cultural diffusion between Turk and Serb had been extensive. The journals of Serbs traveling to Istanbul during this period are quick to note the familiarity of the food and the language (a vast amount of Serbian words, from pendžer (“window”) to džep (“pocket”) were borrowed from Turkish vocabulary).

The 1895 royalist coup, however, destroyed this fragile sense of belonging. As the Muhaberat’s raids netted the leaders within both of the once-dominant parties or forced them to flee, Serb thinkers and activists began to feel that good governance within the Ottoman system departed as quickly as it arrived. Popular treatises on the need for a national revolution, written by political exiles in Bosnia and distributed illicitly in Serbia, claimed that the Balkan people would find long-lasting peace and prosperity when they left the Turks’ grip. The legacy of this disquiet was the rapid growth of the Council of Troops for Popular War (Oдбор трупа за популарни рат, Odbor Trupa Za Popularni Rat). Founded in 1882, OTPR (or Otpor [2], as it was more commonly called) was initially no more than a group of bandits, localized to the environs of Novi Pazar and lacking any more popular support than similar organizations before them. The repression of Abdülmecid’s rule, however, gave it a raison d’etre. Joined by radicalized students, educators, workers, peasants, combative immigrants from Bosnia and even more bandits, Otpor evolved into a united front for the guerrilla forces around the country. Its fighters lived off contributions of supplies, intelligence, and recruits from rural villages, and raided Ottoman arsenals for armaments. The organization as a whole developed a reputation for taking the side of the common tenant of smallholder in confrontations with the landed elite. Starting in 1899, it drew the ire of the Muhaberat and the Ottoman army by destroying buildings of military importance in Belgrade with hastily manufactured explosives. It appeared to sympathetic civilians that the era of the hajduks, the bandits who had protected the hard-driven Serbs from warlord and landlord, had arrived once more.

Despite its rapid rise, Otpor did not enjoy long-term success until the beginning of the Great European War. The rebel leadership, which moved around Novi Pazar and Niš, had very little influence their own movement. The cheta, or small band of fighters, remained the basic decision-making unit despite the inexperience of most cheta leaders. Taing advantage of these flaws, the Ottomans nearly swept the Serbian insurgents off the map between 1905 and 1910. Driven to the south and west, the remnants of Otpor grew dependent on military and financial support from Visegrad, which had sought to enlist the Serbs for its own purposes since the creation of the Patriarchate of Zvornik. Though the Visegradians pledged to stop supporting the “criminals and brigands” if Constantinople refused to involve itself in European affairs, the İki Şehzadeler (“Two Princes,” a common shorthand for the governing duo of Abdülmecid and Mehmed) weren’t interested in the offer. They would win no friends in the capital by meekly taking handouts from the infidels, and so resolved to take a strong stance against problems domestic and foreign. Lacking any real strength of their own, the Ottomans drifted toward France and Lithuania. Neither ally, however, was able to stop Visegrad from shredding the defenses of the Balkans, with only the tiniest sliver of Thracian land remaining in Ottoman hands by 1914. All-Greek and all-Bulgarian national congresses, conducted under Visegradian protection, made declarations of independence. The status of Serbia, however, remained an open question. Though Otpor remained outside the Visegradian chain of command, fought alongside the United Kingdom’ troops as an “allied army,” and declared the existence of a “Serbian Republic” upon its capture of Belgrade, it was tremendously dependent financially on Buda’s beneficence. Furthermore, acrimonious and public disagreements between the leaders of the nascent Republic fatally weakened the public’s confidence in the rebels’ ability to govern. Acknowledging that pan-Slavism was starting to eclipse Serbian nationalism in popularity, the rebel central committee pledged its support for the Visegradian plan to create a “Kingdom of Slavonia.”

Bekrija Market (Belgrade, 1930). Constructed in 1925 atop the ruins of a levelled slum once populated by rural migrants, the Market was one of many “renewal” projects pursued by the Slavonian government.

The Kingdom of Slavonia, fourth and final member of the Visegradian ensemble, consisted of three constituent banates: Croatia, Bosnia, and Serbia. Each governed itself through a local sabor headed by a locally-elected ban, which shared power with the all-Kingdom Diet at Zagreb. This arrangement provided for unity, autonomy, and stability, and while the Serb-nationalist Otpor leadership received credit for helping make it happen it was the pan-Slavists that received most of the public’s approval. Having traditionally shunned Otpor’s strategy of civil conflict, the pan-Slavists were also a natural ally for Visegrad, which preferred that everybody put their guns down now that the war was over. Working through the institutions of the Serbian Sabor and the Slavonian Assembly, pan-Slavist Serbs and their Croat and Bosnian counterparts successfully implemented reforms in the education system and civil service, improvements in infrastructure, and the creation of a regular and professional police force. Even the churches joined the pan-Slavic mood— the unification of the Patriarchates of Zvornik and Belgrade into the Orthodox Church of Slavonia was met with much fanfare. The mid-1920s debate over land reform, however, put a stop to this run of successes.

Redistributing land to smallholders throughout Serbia was, in the abstract, quite sensible— when more families had the ability to independently support themselves and pay more of their new wealth in taxes, both state and public stood to benefit. In the Balkans, however, the question of land distribution was linked almost inseparably with the question of religion. In January 1918, the government of the new Duchy of Bulgaria— barely two years old by this point— announced an ambitious plan for the colonization of the urban and rural areas of the new nation’s southeast with Orthodox Bulgarian families. However, the majority of Thrace’s population was composed of ethnic Turks and Bulgarian Muslims, and they rightly saw the Bulgarian plan as an attempt to rob them of their property without rightful compensation. Protests in the city of Adrianople, which had become a refuge for Muslims driven out of the countryside by the Great War, were met with troop deployments from Tarnovo, reportedly with the express approval of Duke Vatslav of Bulgaria (formerly known as Wenceslaus, nephew of Visegrad’s King Ferenc III). The resulting violence, which spread throughout the province of Thrace over the next two years, compelled around 60,000 Muslims to voluntarily or involuntarily emigrate from Bulgaria by 1920 and even more in the years after that. Proposals for land reform were floated in the Greek Convention after Bulgaria’s twin policy of suppression and deportation began to quell the Thracian violence in 1921. However, Duke Albertos (formerly Albert, cousin of Ferenc III) personal interventions and lobbying of legislators ensured that the Greek reform law of 1922 included guarantees that Muslim and Christian peasant cooperatives would remain untouched and that estate-holders targeted by the reform would, regardless of religion, be entitled to proper compensation even if procuring the funds for compensation required the Greek government to take out loans from foreign banks. A later law provided for the executive cabinet of the Convention, led by the Chairman, to contain a “Deputy for the Muslims” and a “Deputy for the Jews,” both drawn from their respective religious communities. Though the ruling “Progress Party” considered the Duke’s moves as a exemplar of wise, impartial, and far-seeing statecraft that sought to steer the people clear of ethnic and religious hatred, Greece’s populist republicans, including Chairman Grigoris Karaiskos, were quick to call for constitutional constraints on “ducal tyranny.” Amid this instability, many sought to follow the example set by thousands of Bosnians in the mid-1800s and migrate to the Ottoman Empire, but the June Revolution and the creation of the Union made the Ottoman Empire a defunct entity. With nowhere else to go, around 500,000 Muslims settled in Bosnia, seemingly the last place in Europe where Muslims could count on protection from the authorities, over the course of the 1920s. The rest of the emigrants— around 800,000 in total— moved to Egypt instead, where they influenced the direction of the developing Ummatist movement.

In Serbia, a simplified version of the Bosnian government’s protections for Muslims, which provided for freedom of religion and disallowed any confiscation of land from any Muslim landowner, big or small, who had pledged loyalty to the Visegradian state, had been in force since the creation of the kingdom of Slavonia. The debate on the revision of these protections split the pan-Slavists in the Sabor into three rough groups. The blue-wingers argued that the estate-owners were obstacles to progress, and that land reform which targeted large landowners regardless of their religion while allowing smallholders of all creeds to retain their lands would drive Serbian society closer to Weber’s ideals. The “extreme Reds” argued that the ancestors of Serbia’s Muslims had all acquired their lands through theft and that it would be no great injustice for them to be dispossessed by the “stealing back” of land by Christians. The “moderate Reds,” who constituted the original core of the pan-Slavist movement, argued for the retention of the previous protections and the abandonment of land reform, on the basis that large landowners would be more capable than smallholders of investing in methods of modern agriculture and boosting productivity. While the moderates eventually won this debate, the consistent support they received from the Slavonian Diet made them appear to be pawns of higher powers. This attitude was reinforced when the moderate-Red Serbian members of the Diet approved an 1928 amendment to the Slavonian constitution which gave Zagreb the power to regulate commerce between Croatia, Bosnia, and Serbia. Intra-Slavonian tariffs on trade became illegal, allowing Croatian industry to keep dominating the manufacturing sector at the expense of Serbian entrepreneurs. With the onset of the Deluge in the 1930s, the “pan-Slavists” had ceased to be an identifiable political group. The blue-wingers joined a series of similar groups to form the Slavonian Revolutionary Alliance, which in turn became a subsidiary of Gregor Samsa’s Unitarian Congress of Visegrad in 1934. The reconfiguration of the red wing, however, brought an unlikely set of actors to national prominence.

The old Otpor central committee had disbanded in 1920 after failing to beat the pan-Slavists on the field or at the polls. Even among its former members, few missed it. The general sentiment among the former junior officers of the movement was that their seniors had, through their incompetence and arrogance, betrayed the Serbian nation and subjected it to political and economic subordination to other peoples. While the pan-Slavists usurped the glory of national rebirth, the fighters of the cities and countryside were patted on the back for being “good soldiers” and told to find another line of work [3]. Though isolated members of this group ran for and won local offices and seats in the Serbian Sabor in the 1920s, their major contribution to Serbian politics was the publication of memoirs about their experience and the establishment of youth clubs and veterans’ organizations emphasizing physical fitness, academic and professional success, and a sense of civic pride “for the good of the nation.” Organizations affiliated with this “Second Generation” of Serb nationalists (a term used to distinguish them from the “First Generation” that had left Serbia with its incomplete independence) sought out rural migrants to cities, and helped them seek jobs and resolve labor disputes with employers. While quite Protectionist in their religious outlook and eager to force partnerships with the Orthodox Church, they disapproved of the extremist-Red faction, whose attitude encouraged violent disorder and placed barriers in the path of development. Rather than pick on the Muslims, the Second Generation instead aimed at the Croats, who they claimed were “petty imperialists” bent on using the concept of Slav unity for their own purposes. The overall goal of this agitation, in the words of activist and author Miloš Teodosić, was “the creation of representative groups from the sectors of Serb society… [which] will constitute a corporate body committed to Serb nationhood.” While his writings contain many references to this “corporate representation,” Teodosić and many other Second Generation figures seem to have been skeptical at best of democracy— an attitude which endured in their successors.

In time, the Second Generation’s cultural campaign paid dividends in increased popularity for their members and exposure for their ideas— by 1935, a majority of seats in the Serbian Sabor were held by men who professed themselves to be part of the Second Generation or influenced by it. The capture a Slavonian banate by a strongly nationalist party alarmed the men of authority in Zagreb and Buda. A showdown between the various levels of authority, however, never had the chance to occur.

A badge made during the War of the Danube. The crown (Visegrad, order, and tradition) and the double-headed eagle (the Serbian people and their national rebirth) represent the causes which the men and women of the anti-Unitarian resistance fought for unto death (skull and crossbones).

The Hungarian and Bohemian Diets were quickly dissolved by the Unitarians after the Fall of Buda; the Polish Diet had declared itself fully sovereign in April 1939, and ruled with the protection and assistance of Generals Bolek and Lolek. The Slavonian Diet was therefore the only one of the four national assemblies to remain intact and loyal to the King, and was also the first of the pre-Revolution Visegradian institutions to relocate to Germania— not that it had much choice, as the invasion of the CUS from the north and the Union from the south made fleeing to any location within the former Visegrad impossible. Members from all three of the banates’ assemblies also made it to safety, escorted by members of the Slavonian national guard. None of this, however, prevented the Diet from re-enacting the collapse of the Convention of Three Nations in miniature. Though it theoretically remained in session as the official representative of the Slavonian people, the members of the Diet were more concerned with the fates of their respective homelands than in the legislative agenda of a federation which now only existed on paper, and whose main backers were now either dead, missing, or demoralized. Accordingly, power shifted to the sabors, whose members (augmented by defectors from the Diet) had the numbers, the talent, and the motive to begin direct negotiations with German politicians and military figures.

This was especially true for the Serbian Sabor, headed by Ban Marko Dimović. A former independence fighter from the Great European War, Dimović had helped set up an association for unemployed veterans in Kraljevo in the early 1920s. Transitioning from community activism to politics, he was elected for term after term in the Sabor for almost an entire decade by building a reputation of pragmatic willingness to cross factional divides and implement common-sense policy. As part of the nationalist takeover of the Sabor in the mid-1930s, the public elected Dimović for two terms as Ban in 1931 and 1936. Now in exile from his homeland, fighting an enemy more dangerous than the Ottomans had ever been, Dimović led the Sabor in its efforts to mobilize the Serbian exiles in Germania and assist the growing resistance movements in the Balkans.

Even before Dimović’s government-in-exile had any military strength or political legitimacy, its presence helped shape the Serbian resistance. The policemen, soldiers, and activists left in Unitarian-occupied Serbia had little trouble in finding fighters. The population’s literacy rate was almost three times what it had been in 1910, the activities of the Second Generation had brought an interest in politics to even the most secluded hamlets, and the Unitarians made thousands of new enemies with every passing week. However, the question which defined this phase of the struggle was not whether to fight, but what to fight for and who to fight with. Was the struggle merely supposed to drive out the invaders and restore the status quo, or did it aim for political as well as military goals? If the struggle did have political aims, what were they? Would people believe enough in this political program enough to fight for it, or to challenge the views of fellow rebels with different aims? The Sengupta broadcasts of the Serbian government-in-exile dispelled this directionlessness. They granted any civilian or militant living in occupied territory and in possession of a receiver access to news on Germania’s titanic war effort and Unitarian defeats in the north, south, and center. Most importantly, the knowledge that a Serbian government was out there— that it was headed by a competent and popular national leader, armed with a voice that the Unitarians couldn’t suppress, and working every day for the sake of their people under occupation— helped glue the resistance together. Common allegiance to Teča Marko (“Uncle Marko”) helped bridge divides of personality and ideology between mutually distrustful rebel leaders, enabling the resistance to pull off increasingly audacious operations after the spring of 1941.

“Channel Serbia” also figured in the rise to prominence of Jovan Zečević, one of the few major clergymen to have successfully escapes the clutches of the Unitarians. Formerly an extremist-Red bishop in the city of Tuzla, Zečević steadily moderated his views on Muslims in the 30s and drifted toward the Second Generation, but continued to espouse the view that Orthodox Christianity was essential to life as a Serb. In his broadcasts to the occupied territories, Zečević spoke of the need for participants in the revolutionary struggle to not “throw out their morals along with their shackles,” and to encourage discipline in themselves through self-criticism. This message was quite timely, as Orthodoxy and the struggle in Serbia were rapidly moving toward symbiosis. The churches provided shelter and counseling, and the rebels protected churches from Unitarian squads attempting to enforce Denationalization. The activist trajectory of the Serbian church continued even as the resistance itself wound down— in May 1944, an assembly of bishops, which initially gathered in Vienna to celebrate the liberation of Belgrade, elected Zečević to fill the vacant seat of Patriarch of the Slavonian Orthodox Church. The first act of the new Patriarch Jovan III was to honor Augustina Sternberg, who had been strong enough to direct Germania through the traumatic war and courageous enough to personally visit Belgrade after its liberation. The second was to replace "Slavonian" with "Serbian" in the Church's title.

With increasing success came a few superficial changes. The Serbian Sabor changed its name to the Serbian Convention after it became clear that Germania didn’t intend to restore Visegrad, and Marko Dimović adopted the title of Democrat shortly after the Schönbrunn Declaration. What few observers failed to note, was that Dimović was not in good health. In the 1920s and early 30s he’d been known for working like a well-oiled machine, and perhaps even for working too efficiently. In the years after his 57th birthday in 1942, Dimović’s mind wandered; at times, he seemed to have no clear idea of what he was supposed to be doing. The servants at his Vienna household would later tell of his sudden mood swings and his tendency to ask that they complete tasks which they had already completed. His typical cleanliness and punctuality slowly dissolved as well. The complete truth about Dimović [4] was concealed as much as possible from the world— the fiction of a strong Serbia needed to be preserved. Even the Serbian Sabor was typically informed that Dimović sudden absences or erratic behavior was due to “exhaustion” and “lack of sleep.” The chief conspirator in this ruse was Novislav Đajić, Dimović’s bodyguard and secretary. With the cooperation of the other members of the Ban’s household, Đajić made himself the sole route of access to Dimović, granting appointments with his employer to men that he trusted (a group that did not include Patriarch Jovan) and denying them to men that he didn’t. Đajić’s de facto status as Dimović’s chief assistant, closest confidant, main envoy to the Sabor, and possible heir was confirmed when Dimović nominated Đajić as his Deputy Democrat in 1944.

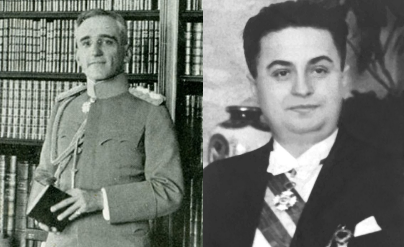

Marko Dimović (left), and Novislav Đajić (right).

The German occupation authorities in Serbia theoretically presided over the first all-Serbian government since 1939 (the CUS and the Union had split the country down the middle, taking the south and north respectively) but decentralized and autonomous structures governed most day-to-day affairs between 1944 and 1948. Although the Serbian resistance had shared a unity of purpose, most of the larger armies retained separate commands and regarded each other as allied but distinct forces. The interregional influence of powerful commanders like Novak Bulatović (the strongman of of the Raška and Šumadija districts in central Serbia) or Ana Kostić (the “Tungsten Woman” of the eastern city of Niš) never transitioned into firm control of the movement on a national level. By choice or necessity, most militants accepted the authority of the Germans and swore allegiance to the Serbian government-in-exile, which returned to Belgrade on January 1, 1946.

The first years of the Second Serbian Republic saw the reconstruction of the shattered bureaucracy and emergency service networks, cession of power by militants to civilian administrators in districts surrounding around the capital, vast enlargement of national territory through the referendums conducted by the Germans, economic rebirth fueled by the demand for reconstruction and German development aid, and an orderly election in which Dimović won a second term. The 1949 “Večernik Papers,” however, broke sharply with this line of successes. The papers in question, provided by an anonymous member of the Convention and published by the Serbian newspaper Večernik (“Bringing news to the Serbs, above ground or underground,” as its tagline claimed), revealed that certain circles within the government had been embezzling German foreign aid. The exposure of the plot led to the first (and last) overt conflict between the theoretical apex of the government and the man who actually controlled it— while Đajić vehemently denied the veracity of the Papers and demanded that they be retracted, Dimović paid an unexpected visit to the Belgrade Sengupta station. Without the prior knowledge or cooperation of any other major government figure, Dimović promised that “I don’t really know much about what happened, and I’m sorry… terribly sorry for that. But whatever happened, the Serbian people deserve to know.” However, no investigation was ever actually initiated, and Dimović soon disappeared from public view completely as his health worsened. In January 1951, Democrat Marko Dimović died in the same hospital where he had spent the previous eight months. Novislav Đajić, who had already served as Acting Democrat for the same amount of time, was selected by the Convention to serve out the remainder of Dimović’s six-year term.

Dimović’s reputation had taken quite a tarnishing due to the corruption which occurred under his watch, but the Đajić years soon proved that Teča Marko had had almost nothing to do with it. Rather, the suspicion of the people shifted to Đajić, whose authoritarian governing style appeared to be informed by more than just a simple need for control. By avoiding major reforms or new programs in the name of “encouraging stability,” Đajić made sure the government had no need for a massive influx of employees. This allowed his circle to screen applicants for public-sector jobs more thoroughly, and weed out potentially “subversive” elements. The definition of “subversive,” however, did not include Serbs who had formerly served the Unitarians. Instead, the new “Republican Guard” was a virtual haven for low-ranking national traitors, who had blended in among the masses while more prominent figures within the old Slavonian Revolutionary Alliance were tried by German courts for collaboration with the enemy. While the creation of the Guard in 1949 was not unexpected— after all, the government needed a military force that would be exclusively loyal to it, and not to the former militant commanders— it would become a thoroughly reviled institution by 1952. By then, its primary purposes seems to have become protecting Đajić and his allies and covering up this powerful group’s misconduct. Many years later, a cache of discovered memoranda and letters revealed the extent of the web of patronage and obligation that Đajić built around himself. He convinced his former partners in the embezzlement ring to contribute to the Republican Guard’s budget by arguing that the Guard was the only thing protecting them from the consequences of their actions. The role of the Guard in insulating former Unitarian enforcers and hired guns from justice also appears to have been quite deliberate.

While the 1949 election had been almost a formality, the 1955 election was the most contentious in Serbian history. The main opposition candidate was Milan Ivanović, a retired member of the Convention who revealed in the early stages of his campaign that he was the whistleblower who released the Večernik Papers. Patriarch Jovan III threw in his lot with Ivanović, proclaiming that Đajić had allowed himself to veer far off the Christian path, and failed to critically review his own conduct. Considering the value which the anti-Unitarian struggle had placed on personal discipline and devotion, the Patriarch’s accusations essentially implied that Đajić had betrayed the revolutionary ethos. Đajić, for his part, responded— and perhaps a bit too strongly. He was at first content to hit back at Ivanović by accusing him of the same “factionalism” which had made the First Serbian Republic unviable, and accuse the Patriarch of trying to make a “pet Democrat” of Ivanović and threaten the safety of the Muslims who had not already moved to Bosnia. By October, however, Đajić had resorted to using the Republican Guard to intercept paper bound for Večernik’s presses to keep its editors from marshaling the campaign against him. When Patriarch Jovan spoke out against this measure on the 20th of October, the Guard arrested him two days later. The response to this latest outrage was immediate and sweeping.

Đajić had called his opponent a rabble-rouser "whose presence is not required in a still-unstable country," but the Patriarch was capable of rousing more than just rabble. On the first of November, thousands of Serbians from all walks of life filled up Belgrade’s Prince Lazar Square, blocking the roads running into the square with barricades. A rash of strikes crippled industry in the capital and in the new territories annexed after the German-sponsored referenda, and civilian demonstrations against the Republican Guard grew increasingly organized after the first week. Thousands of compatriots from the provinces joined in until Đajić ordered the Republican Guard to shut down the trains. In doing so, he sealed his fate.

The Serbian Army, whose leadership was dominated by former militants, had initially approved of Đajić because of the belief that there was no better choice. By 1955, the situation had changed. With the resumption of civilian rule over Serbia’s subnational divisions, soldiers and commanders had lost the ability to “live off the land,” and became dependent on the military hierarchy to provide them with resources and salaries. The ranks of the old guard were also thinned by “civilianization,” in which militant commanders willingly sought out jobs in the civil or foreign services or were ordered to do so by Belgrade, and those who remained in military service had an easier time of reaching a consensus on key issues, which included (but were not limited to) an official policy of hostility toward the Republican Guard. All this meant that the Army of 1955 was more centralized, self-confident, and dissatisfied with the status quo than any previous military force of modern Serbia. The order to stop the trains, which exceeded the range of options permitted to the Democrat by the constitution and undercut the authority of the Army, lit the powder keg. Holding high portraits of Patriarch Jovan, the 26th Serbian Rifles convinced the demonstrators in Prince Lazar Square to take down the barricades and let other Army units pass through the city uninterrupted. In the space of three days, most of the Republican Guard units had been compelled to lay down their arms. On the 10th of November, Đajić’s family disappeared from Serbia along with a large portion of the Democratic Palace’s movable property. The next months would see the deposed First Family turn up in Hungary and France before they departed for Mejico, never to return.

A council of officers led by General Novak Bulatović formed a provisional government in the aftermath of Đajić’s flight, but this was perhaps not the same thing as “seizing power.” One had the sense that the most powerful man in Serbia did not occupy an office, but rather a Republican Guard detention center. And as he walked free of his prison, through crowds of thousands who had been ready to suffer even death on his behalf, people wondered: What kind of man was Jovan Zečević? How had a movement so large grown so quickly around him? And now that he was free of his cage, what did he want to do next? Whatever he demanded, would anyone refuse him?

Citing Milan Ivanović’s personal involvement in the corruption detailed by the Večernik Papers, the provisional government declared him unfit for office and suspended the elections. After three months, General Bulatović declared that the powers granted to the Democrat in the constitution were far too sweeping, and that elections would remain suspended until the creation of a new constitution, at which point the well-intentioned but ultimately irredeemable Second Republic would give way to a more perfect Third. The ensuing Constitutional Congress lasted for three months, featuring a mix of soldiers, clergymen, lawyers, professors, and student activists. In June 1956, General Bulatović announced that the provisional military government would disband and that Petar Popović, a professor with no political experience outside his time in the Constitutional Congress, would serve as Acting Democrat until elections in 1961. Many of the powers previously vested in the office of the Democrat, however, were transferred to the newly-created post of Premier, which assumed a number of rights ranging from issuing decrees with the force of law to dismissing the Democrat and calling new elections.

Jovan Zečević, 41st Patriarch of the Serbian Church and first Premier of the Third Serbian Republic.

Germany, and Europe in general, had been far too distracted by the Great Asian War and its (literal and figurative) fallout to respond adequately to the Serbian Revolution of 1956 or the events leading up to it. Even if they had not been distracted, it’s unlikely that they would have done anything to support the unpopular and ineffective Đajić. Furthermore, the new authorities in Belgrade were cooperative enough. The Third Serbian Republic was interested in maintaining the European Defense Commission, and sent a contingent to troops to aid West Turkey in the Two Weeks’ War of 1958.

By 1960, however, it became quite apparent that Serbia’s turn to theocracy under Patriarch Jovan's guidance would continue whether it was convenient to the interests of foreigners or not. The arduous decades had left the Serbs distrustful of secular authority. The period of democratic rule under Visegrad devolved into rule by the lobbyist and the political machine, in which the nation, regardless of what it voted for, was subject to economic and political forces outside its control. The Unitarian occupiers were failures in every sense, and their radical atheism hardly helped matters. The short period of secular nationalist rule under the Second Republic showed some promise but even this was ruined by the innate corruptibility of modern government, which insisted that it was an advocate of the people but answered to no higher authority than itself.

The Third Republic, however, gave state institutions a higher authority— the Premier— that wasn’t just an abstract and easily abusable concept like “the people.” The belief that a man of the Church could be trusted with such a role (in 1959, a constitutional amendment formally made the Premiership synonymous with the Patriarchate) seemed more natural than one might imagine.

Rough diagram of the power structure in the Third Serbian Republic.

Since the earliest times, allegiance to some form of Eastern Orthodox worship had been a symbolic characteristic of Serbian nationhood. That devotion accrued practical political significance during the ecclesiastical experiments of Visegrad and the Ottomans, in which the recognition of the Serbs as a nation separate from the other peoples of Rumeli came with the creation of autonomous church structures. Patriarch Jovan’s positive contributions during the period of war and national reconstruction ranged from the more well-known activities discussed earlier to equally consequential acts like keeping the faith alive in the refugee camps in Germany, collecting and preserving old texts salvaged from the ruins of monasteries and private collections, and heading the ecclesiastical committee to nominate new church officials to replace those who had died in the war or collaborated with the Unitarians. The reputation of trustworthiness and tirelessness that the Patriarch and his allies in the Church built up among the public allowed them to not just challenge political norms, but scrap them altogether.