During the Avar siege of Constantinople in 626, when there was a lull in the fighting, residents of the cities would pick vegetables from the gardens between the walls of Constantine and Theodosius (Gilbert Dagon, “The Urban Economy, Seventh-Twelfth Centuries,” in The Economic History of Byzantium, 448-49.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Revival of Rhomaion: An Age of Miracles

- Thread starter Basileus444

- Start date

1552: Timur II’s crossing of the Zagros Mountains receives less attention in Constantinople than three other events. First is the birth of twins, a boy and girl, to Theodora and Alexandros in January. The healthy infants are named Anastasios and Anastasia respectively.

Two months later the Empress Helena gives birth to a son, Andreas. The birthing is extremely difficult and painful, with the Empress in labor for a day and a night. Andreas though is healthy, the midwives marveling at his size; according to Theodora at birth he weighed twelve and a half pounds.

The other is the coronation in Kiev of Dmitri I, Great King of the Rus and Grand Prince of Lithuania. Twenty four years old, he is well aware of his purple blood, as he is the great-grandson of Andreas Niketas and Princess Kristina of Novgorod, via their daughter Helena. Prone to sudden mood swings, he is quite vocal about the fact that by blood claim he has a much better right to the throne of Rhomania than its current occupant.

However he, or more properly his advisors, are not crass enough to claim that said throne belongs to Dmitri. The ponderous speed and extreme casualties taken by the Army of the North during the Orthodox War proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that a credible projection of Russian power by land south of the Danube was only possible at an exorbitant price. And at sea, the Roman navy is still almost three times more powerful than the Russian Black Sea, Vlach, and Georgian fleets combined. There is also the matter the Scythia is economically much more inclined to Constantinople than Novgorod, with 2.5 times more exports to Rhomania than to the rest of Russia.

Still, because of his ancestry Dmitri tends to present himself as the leader of Orthodox Christendom, and he toys with the idea of dropping the Roman-bestowed title and crown of Megas Rigas in exchange for a more grandiose title, perhaps ‘Tsar of all the Russias’. But it also difficult for him to break Russian tradition, thus he is unable to commit to either course of action, mainly serving to irritate Constantinople even as in Munich Kaiser Wilhelm solidifies his power by instituting a tour system of his own in Bavaria and Schleswig-Holstein, overseen by Templar administrators.

In Marselha and Avignon on the other hand the main debate is what to do about this new development in Mexico. Although King Basil is irritated that his uncle is insistent on ruling an independent realm he does admit that legally there is no reason for him to expect David to do such a thing. The whole expedition was financed by David personally.

However there is still a way for Basil to benefit from the situation. Emperor David is well aware of the technological backwardness of Mexico compared to the Old World, and equally aware that the few dozen blacksmiths and carpenters in his expedition are nowhere near enough to solve it on their own. His breeding stock for horses is also extremely limited, with inbreeding inevitable considering he only has five healthy stallions.

So the solution is trade. Arles will provide experts and materials, especially swords, armor, cannons, and horses which Mexico cannot make, as well as horses and other livestock (pigs soon become preferred by the Mexicans) in exchange for silver. The bullion mainly comes from the mines of Zacatecas, often worked by captives from the Tarascan war. Although the initial Tarascan invasion was smashed flat in battle by David’s army, he is unable to follow up the advantage due to the diseases ravaging the peoples of Mexico and his need to solidify his hold over his domains.

The Avignon Papacy, under Pope Paul IV, is not nearly so sanguine about the situation, and is disturbed by the lax nature of Mexican Christianity and David’s dilatoriness is fixing the situation. Priests are dispatched across the sea, and while Paul IV does recognize that the true conversion of Mexico will take time, he does expect to see progress to that end. If not, he holds out the possibility of papal approval and support for an Arletian or Portuguese-Castilian expedition. It is a threat David takes very seriously, well aware that there is no rule written that only the first invasion of Mexico can possibly succeed, despite the claims of some of his men who are busily marrying into the Mexican nobility.

In the east, before Sultan-Khan Timur II sweeps south into Mesopotamia, he meets with Princess Theodora on the shores of Lake Van (her two children remain in Constantinople). Their two-week conference is to help set the groundwork for the new order in western Asia. Trade negotiations are formalized and an extradition treaty signed, with both parties swearing eternal friendship. The trade between the two increases, with Timurid horses and astronomy texts flowing west as Timur adds Roman medical treatises to his personal library.

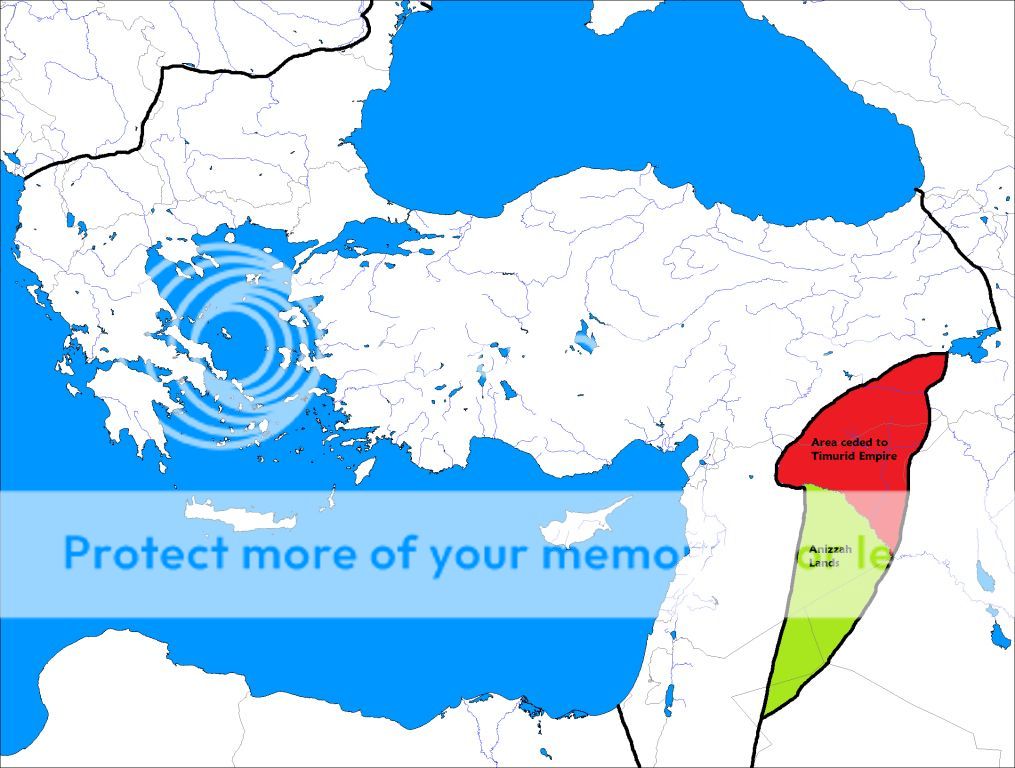

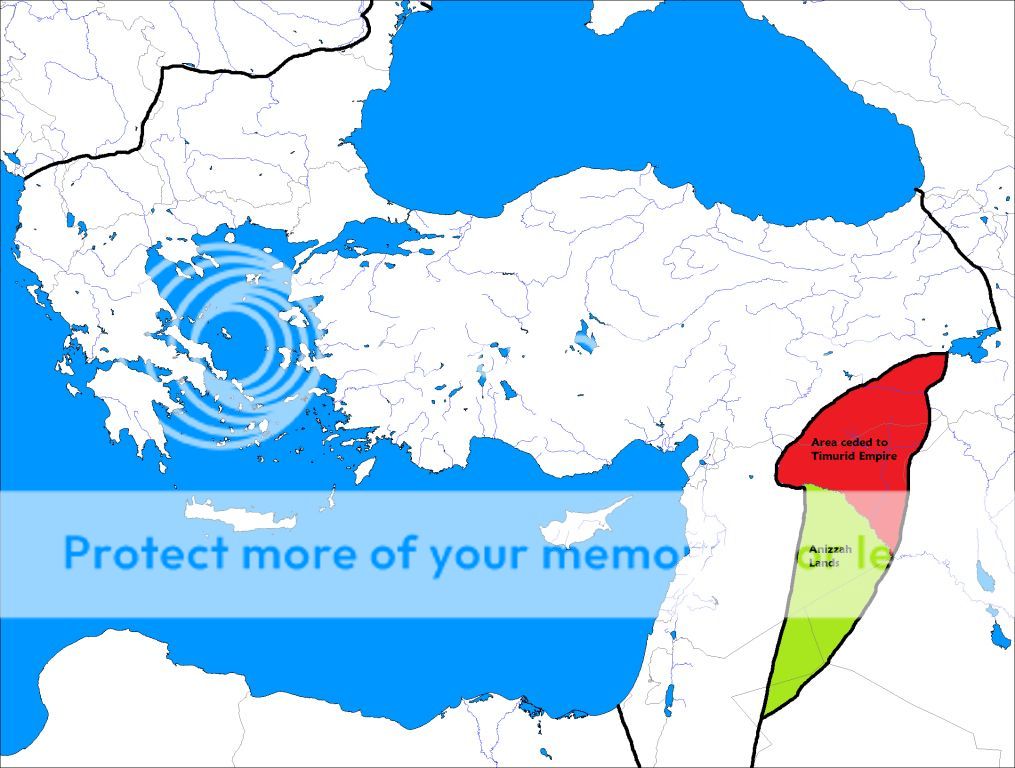

But far more momentous is the Second Treaty of Van. In exchange for an absolutely massive cash payment that wipes out over half of the Roman debt and almost four-fifths of its interest payments (by using the Timurid cash to pay off the higher interest loans early), most of the Roman territory beyond the Euphrates is ceded to the Timurid Empire. At the same time the Anizzah are given autonomous control over much of the remaining Syrian frontier as a Roman vassal (although not as a Despotate), on the grounds that Roman power projection is extremely limited anyway and that it will make the Anizzah defend the area even more fiercely.

Besides the money, the Treaty pulls the frontier back to a more defensible area in Helena’s eyes. The border is now where it was for most of the fourteenth and fifteenth century, with a much more developed infrastructure and fortress belt, although the latter does need to be modernized. Border defenses can now be more cheaply upgraded by building on the previous Laskarid structures, and better supported thanks to better and more roads and shorter supply lines. Plus it gets rids of another 100,000 Muslims that the Empire doesn’t want, fixing the border amongst more Christian and loyal peoples.

Despite that, the army is utterly outraged by the ceding of a large block of Andreas Niketas’ conquests, and one of the last remaining in Roman hands. Nikolaios Polos, recently promoted to Megas Domestikos, is so livid that after a shouting match with the Empress he storms out of the White Palace. He is gone from the capital for almost four months, coming back only when his wife flat out orders him to return. Also many of the peoples of the east are not happy over the loss of a buffer zone, especially the Edessans, now the terminus for one of the Skopos lines (the one that previously ran to Nisibis; the Palmyra line now ends at Damascus).

As for Timur II, the treaty of Van significantly bolsters his position amongst the inhabitants of Mesopotamia by removing the looming specter of a Roman invasion from them. With a buffer zone between them and the Empire they can sleep easier, and can be expected to be grateful.

Marching south towards Baghdad, he faces little opposition until he actually besieges the Ottoman capital. Sultan Bayezid III has made no attempt to flee, although he has dispatched the treasury and his family to Basra. The defenses of the city have been repaired and improved since Andreas Drakos sacked the metropolis, and the smaller population of forty five thousand is able to defend the city without unduly taxing the stores of supplies.

Thus for three months Bayezid is able to keep Timur out, despite his thirteen batteries of Roman cannon. But on October 11, the city is taken, the Ottoman Sultan killed in battle defending the Topkapi Palace at the head of his few remaining janissaries. Timur keeps the sacking limited to just the eleventh, reproaching a soldier found hacking out pieces of the marble floor of the Topkapi palace, as the buildings belong to him. Entering the Mosque of Osman I, he sprinkles dust on his turban as a gesture of humility, quoting a line from the Iliad:

“The day shall come in which our sacred Troy

And Priam, and the people over whom

Spear-bearing Priam rules, shall perish all.”

In Basra, Bayezid’s eldest child and daughter reacts to the news not with grief but with boldness. In an epic ride across enemy-occupied territory, carrying a fortune in jewels sewn into her and her retainers’ clothing and accoutrements, narrowly avoiding capture on at least three different occasions, she arrives in Sari, the capital of Osman Komnenos. One month to the day after the fall of Baghdad they are wed, her husband formally claiming for the first time the title Shahanshah.

Three days later the Georgian army, under the command of the Grand Domestic Stefanoz Safavi, takes Tabriz, putting every member of the Timurid garrison to the sword.

1553: The sudden and explosive onslaught of the Georgian army comes as a complete surprise to all of its neighbors, including the Romans. Ever since the Orthodox War the Kingdom of Georgia has been a diplomatic non-entity due to its tremendously high losses, and those states bordering it have grown complacent.

It is an understandable mistake, but a bad one, for the force that ushers forth to finally avenge the sack of Baku is the most powerful the Kingdom has put into the field since the days of Thamar the Great three centuries past. The army is a smaller version of the Roman host, but excellently equipped with lamellar armor and gunpowder weapons, although given the terrain of Georgia heavy siege guns are a rarity. Alan light cavalry and Azeri light infantry provide a formidable screen for the heavy troops, of whom pride of place goes to the King’s Immortal Guard.

The areas, besides size, in which the Georgians fall short by Roman standards, is in training and logistics. There is no equivalent to the School of War for officers, although there is an institution for the training of artillerymen and engineers. Nor is there a War Room to organize war plans or march-tables, and Roman quartermasters have little good to say about Georgian logistics (to be fair, that is true for everyone save the Bernese).

Thus Stefanoz Safavi’s sudden riposte that seizes Tabriz stalls after the fall of the city. His ammunition stocks are depleted, rations are short even with Tabriz’s stores, and the winter campaign, although granting the inestimable advantage of surprise, has taken a hard toll in frostbite on men and horses. It is not until May that the army is ready to move again.

The fall of Tabriz severed the main route through which Roman-Timurid trade had been conducted. The Great East Road, linking Chalcedon to Theodosiopolis via Ancyra, plus the Black Sea route to Trebizond (connected via a spur line), had dominated the scene during its brief flowering. Partly that was because of tradition, as when it was established the more southerly routes led to Ottoman territory. But also most of the Roman shipping in the eastern Mediterranean is taking advantage of the oriental routes once again flowing into Egypt, plus the slave trade with Ethiopia.

Still, Timur II already has an impressive stock of Roman armaments to supplement his own manufactures. He marches north, and given the size and skill of his army, there would be every reason to suspect that the Georgians will pay dearly for their audacity.

But Timur II does not face just the Georgians. For Tieh China has once again stirred. Bested in iron, it has turned to gold, and summoned forth a volcano. Ever since its birth, the Kings and later Governors of Urumqi had played a delicate balancing act between the Han and Uyghur elements of the states, with steadily declining success due to Tieh intrigue. In the spring, a full blown Uyghur insurrection erupts, and supported by Chinese gold and arms, obliterates the city of Urumqi, its governor, and his army, ending the two-hundred year old state and replacing it with a Uyghur tribal confederacy under Tieh influence.

With the threat of a two front war against Timurid Samarkand and Urumqi destroyed, the proud Uzbeks, resentful of their long vassalage to the line of Timur, have also begun to move. At their side are the riders of the White Horde, veteran troops bloodied in raids against Russia and the Cossack Host. Together they invade Transoxiana, the heartland of the Timurid Empire. Even the Cossacks join in, although not jointly, supported by a few battalions of Russian regulars shipped down the Volga as Georgian ships basing out of Baku harry the eastern shores of the Caspian.

In the Indian Ocean, the Emirate of Oman has gotten itself into a shooting war with the rising maritime power of the Emirate of Sukkur, which is solidifying its hold over the Punjab and the Rann of Kutch. Already the Kephalate of Surat pays the Emirate a small retainer as protection money. Thus the Omani fleet is unable to stop the counter-attack from Basra which retakes Bahrain, although Hormuz remains firmly in Omani hands.

But the threat of Omani raids is lifted, freeing the garrisons of southern Mesopotamia. They are also reinforced by an influx of Arab riders from the Najd, the losers of a tribal war with the House of Saud, Lords of the Najd and Sharifs of Mecca. No match for the Timurid army in open battles, their pinprick raids are a source of serious annoyance to Timur, disrupting his cultivated persona as protector from the Treaty of Van.

Forced to draw off troops to guard his southern front, contain Osman in Mazandaran, reinforce the defenses of Transoxiana, and guard against a number of Khorasani forays westward, the Georgian and Timurid armies are evenly matched in number when they array for battle at Takab, Stefanoz Safavi placing his command post in the ruins of the ancient fire temple. Timur II is stronger in cavalry, Stefanoz in number of artillery, although the Sultan-Khan has more heavy long-range ordnance.

Going onto the defensive, Stefanoz guards his front with a row of wagons, linked with iron chains which are guarded by cannons and pikes, with gunners firing from behind the barricade. His cavalry is posted in reserve and as flank guards, with a cloud of skirmishers deployed forward. It turns out to be a bit too far forward, as the Timurid horse eviscerate the screen and send it flying back in disarray.

Timur follows up his advantage, charging forward as squadrons curl around the flank as the Georgian ranks are disordered by their backpedaling skirmishers. The center of the Georgian line, held by the King’s Immortal Guard and its fearsome artillery, repels the attack. However the left wing, less stoutly defended and under an attack well supported by Timurid cannonades, is smashed to pieces.

Timur has victory in the palm of his hand, but his troops instead of rolling up the Georgian lines take to plundering his camp. Horse assigned to outflank the Georgians join in the pillaging, freeing three droungoi of Immortal cavalry which Stefanoz personally leads in a counter-charge.

Now it is the Timurids flying back in disarray as all along the line the Georgians counter-attack. Timur commits his reserve, but is struck by a fragment of Georgian shell. Knocked unconscious, he is carried from the field along with his army, which retreats but in good order.

Both sides suffer nearly thirty percent casualties, with historians to this date debating whether it constitutes a Georgian victory or a draw, as the Georgian offensive collapses. But Timur is unable to try for a rematch as rumors of his death encourage the Turks and Arabs of Basra to march north, placing Baghdad under siege.

Timur returns to the city, mauling the Turco-Arab army, and then wheels east to thrash a Khorasani army that had penetrated into the Iranian plateau. Yet though everywhere save Takab he is victorious, everywhere his lieutenants suffer defeat. Osman Komnenos routs the Timurid army facing him, killing its commander, and forges an alliance with the Khorasani with a marriage between the Emir and his second daughter by his first wife (Aisha is his third in number, although first in rank and favor) and payment of subsidies.

With his new allies, Osman seizes the city of Gorgan, on the southeast corner of the Caspian Sea, and shortly afterward establishes control over the ancient Great Wall of Gorgan. Timur is cut off from Transoxiana where the viceroy of Samarkand had nearly won a victory over the Uzbeks, before the tide was turned by the Khan’s bravery, the battle ending in a smashing Timurid defeat.

Retiring westward, Timur knows he must smash at least one of the foes facing him. If he can do that, it will give him the breathing room to turn around and crush the others. In the words of Nikolaios Polos, the Sultan-Khan is ‘a bear beset by a pack of dogs’. Crushing a Georgian contingent near Hamadan, the victory is more than nullified by the news that his rearguard has been cut to pieces by Osman and that Baghdad has fallen by treachery. Shortly afterwards Osman links up with the Turks and Arabs of southern Mesopotamia who pledge loyalty to him as Shahanshah, while he in turn promises to hold true to the traditions and customs of his Ottoman ‘forefathers’.

Timur’s army, worn out by constant battles and marching, is forced to retreat even further west, Osman in pursuit with an army now outnumbering his foe five to two. Still the heir of Timur the Great and Shah Rukh must be feared, as a tremendous backhand blow administered on Osman’s vanguard seriously bloodies it. The pursuit is soon resumed, but it is delayed for a crucial few days. On October 14, Osman appears in full battle array near the ruins of Rakka, known as Kallinikos to the Greeks. On the other side of the Euphrates, guarding the ford, is Nikolaios Polos and the Roman Army of the East. The Shah is six hours late; Timur II and his army have been granted sanctuary in the Roman Empire. All that remains is to cross the river.

Western Bank of the Euphrates, Near Rakka, October 14, 1553:

The sounds of cannon fire was rolling off from the horizon. It was a sound with which Nikolaios Polos was quite familiar. In fact, it was a sound he longed for. He was a soldier; war was what he knew, what he was good at. Peace was not for him. Especially not this peace, he snarled.

The Sultan-Khan had been granted sanctuary in the Roman Empire, but he had been forbidden to cross the river, to enter foreign lands. Foreign! That land is Roman, won by Andreas Niketas himself! It had been sold to Timur like a cobbler sold a pair of shoes, but his wife insisted that even though Timur could not hold those lands, they would not be reclaimed. Instead Osman would be allowed to move in without comment.

The Sultan-Khan had been granted sanctuary in the Roman Empire, but he had been forbidden to cross the river, to enter foreign lands. Foreign! That land is Roman, won by Andreas Niketas himself! It had been sold to Timur like a cobbler sold a pair of shoes, but his wife insisted that even though Timur could not hold those lands, they would not be reclaimed. Instead Osman would be allowed to move in without comment.

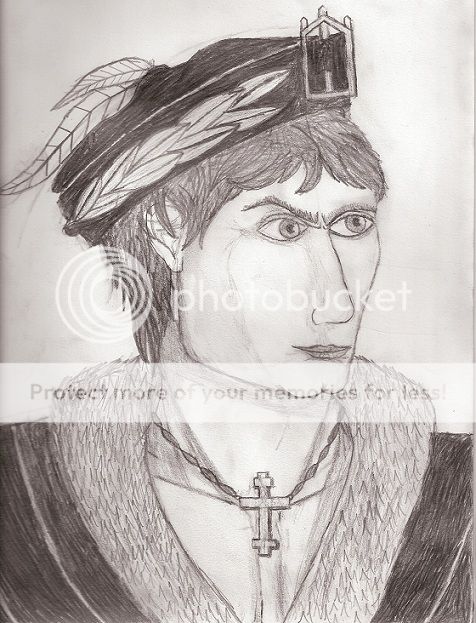

Helena had had a crush on him since she was fourteen. Nikolaios had never, even when she flowered into womanhood, reciprocated those feelings. But never had he expected that he would come to hate the eldest daughter of the man he regarded as a second father, a man who had treated him like a son.

There was a very good reason why he had not entered the list of suitors vying for the Empress’ hand; he was already engaged at the time.

But Helena had wanted him as her husband, and she always got what she wanted. Not even Andreas Drakos had been able to say no to her. The engagement had been hurriedly broken off by Anna’s father, terrified of impeding the Empress’ desire, whilst grief-stricken Anna had become a nun at a cloister on the outskirts of Nicaea.

But Helena had wanted him as her husband, and she always got what she wanted. Not even Andreas Drakos had been able to say no to her. The engagement had been hurriedly broken off by Anna’s father, terrified of impeding the Empress’ desire, whilst grief-stricken Anna had become a nun at a cloister on the outskirts of Nicaea.

So he had married Helena Drakina, the most powerful, wealthiest, and acclaimed by many men to be the most beautiful woman in the world. He loathed it. He wasn’t her husband, he was her consort, her breeding stud. He was pretty sure she had listened to him once, on what kind of soup to have with dinner.

Well, that wasn’t true. She listened to him and followed his advice regularly, except that was solely in matters when he was acting as a strategos and she as an Empress. He had no problem with that, but I could have done that and had Anna as well. Bitch.

A spout of water gushed up from the eastern bank of the Euphrates. Timur II was retiring in good order, but he was hounded by Osman’s forces, and a retreat across a narrow ford whilst under attack would be an exceedingly difficult maneuver even for the best of troops. And he was forbidden to engage Osman.

Three more waterspouts leapt up. Save to defend yourself and the Empire. That was his escape clause. He had read the treaty of Van, before using it as toilet paper. The texture had been wrong, but he had still enjoyed it. And the treaty had never specified who owned the Euphrates where it acted as the frontier, so as far as he was concerned Osman was shelling Roman territory.

“Droungarios Michael,” Nikolaios said. “Light the rockets.”

“Yes, sir,” the Cilician Armenian said with a huge grin. Clad in the light gray uniform that was now standard for the Roman army, worn under a burnished steel cuirass, the tall officer bore a large and vicious scar across his left cheek, courtesy of a Turkish scimitar during the siege of Antioch.

He nodded to the Castilian who stood next to the signal rocket batteries. To fill the ranks, foreigners, even Latin ones, had been recruited, provided they learned Greek and followed Roman military discipline. The man took the torch and lit the fuse of a rocket which screamed skyward. The second lit, but sputtered and blew out its bottom, falling to the ground as a tetrachos threw a bucket of water on it. “Misfire,” Michael said.

“Reload.”

Again a rocket shot up into the sky, exploding at about a thousand feet. The second followed this time, and moments later a third joined it.

Timur wiped sweat from his brow. “Order the Bukharans to abandon their heavy guns. They’re just slowing our march down. Deploy the Samarkand and Bukhara light guns here and here.” He pointed to the map pinned to his two foot by two foot board strapped to the back of his horse’s neck. “Their fire will mask our retreat. Keshiks and Samarkand troops will deploy as rearguard, spiking the guns before retiring.”

“My Sultan!” one of his Keshiks shouted, pointing to the Roman lines. Timur wasn’t sure of what he felt looking at that array. It claimed to be sanctuary, but he had not forgotten that it had been Roman armies that had been the greatest challengers to Shah Rukh and his great namesake.

A white streak of a rocket blazed up and then exploded. Nothing happened. “What does it mean?” one of his officers asked.

Then one after another, three more arced up, shooting toward the sun. “It’s some kind of signal,” Timur said. But what kind? All the rockets were coming from a small promontory on the left bank of the river, one which gave an excellent view of the battlefield and thus a first-rate position for a command post.

For a few seconds nothing happened, and then as one the entire Roman line belched fire, the roar of cannonballs and screams of rockets flying eastward. Is this how it ends? Timur thought. At least it is a mighty end. The terrible projectiles flew, and flew, and flew, and slammed straight into Osman’s left wing. He could hear the screams, even as another fifty rockets leapt out from the Roman lines. Or perhaps not.

Nikolaios grinned as the cannons and fire lances poured their salvos into Osman’s lines. “Order all batteries to commence battle fire, full speed until their ammunition is expended or otherwise ordered.”

“The batteries will run hot,” Michael said, following his part of the script perfectly.

“Deploy men to ferry water from the rivers.”

“They’ll be exposed to enemy fire.”

“You’re quite right,” Nikolaios replied, scribbling on several pieces of paper. “We will need to guard them. Order the following tourmai to deploy across the river at all speed.”

He handed the forms to Michael. “Yes, sir!” he shouted, whooping as he galloped off to the knot of couriers and scribes deployed a bit to the rear.

It was only ten minutes or so before Nikolaios saw the boats crossing the river as engineers began throwing pontoon bridges together. The equipment had already been positioned for this moment; Nikolaios had no intention of deploying through the ford, not while Timur was attempting to cross it. Battle was no place for a traffic jam.

A few minutes later Michael galloped up. “Droungarios Alexandros, 3rd Syrian, begs to report that the eagle has landed!”

Nikolaios laughed. “Well done, well done.” The gray uniforms had not been the only innovation taken from the Antiochenes, but also the return of the Imperial eagle standards, one for every tourma. He could hear the crackle of arquebus fire as the mauroi let loose on their foes.

He smiled. He had defied the bitch. And perhaps…Nicaea is on the way back to Constantinople…he would do it again.

Timur again wiped sweat and dirt from his brow, blood coming with it from a head wound. It had been a hard day, a tiring day, but he had successfully extricated his army and all but six heavy guns from the hands of Osman Komnenos. The Romans had been invaluable, and they had paid for their aid heavily. The troops ferried across in small boats or marched across the light, hastily-built pontoon bridges had by necessity all been light infantry.

For the most part they defended themselves well with arquebus volleys and artillery support from across the Euphrates. Helping them had been some braces of rockets they took with them, and light, pre-made field works and caltrops to cover their position. But even so, Osman’s cavalry charges heavily cut up some formations which had fired too early and been overrun before they could reload. Others had been rescued only by Timurid lancers forming on their flanks in support.

Both owed the other much this day, and had fought side by side as the enraged Osmanli forces stormed across the ford, the Roman bridges blown as the mauroi retired. Timurid and Roman cannons had poured enfilading fire onto the assault columns, a mass charge of Roman kataphraktoi and Timurid lancers sweeping the survivors into the river. The Euphrates, red with blood, was coated in Osmanli dead.

And now it was time to meet his ally, the Megas Domestikos of the Roman Empire, who was waiting for him at his command tent. Timur II smiled as he heard the sounds coming from the Roman camp and sentries, shouting back across the Euphrates. For he spoke Greek, and he clearly recognized the song Do you hear the people sing?

He rode into the Roman camp, flanked by his dirty keshiks, their arms stained by Osmanli blood. The Roman soldiers, similarly stained, looked at him as the Megas Domestikos rode forward, and then took up a new call.

“TIMUR! TIMUR! TIMUR!”

The Megas Domestikos dismounted in front of him and smiled. “Welcome, my lord,” he said. “To Rhomania.”

1554: The Euphrates ‘Incident’, as it is called, has a combined total of almost ten thousand casualties from all sides. Osman Komnenos cuts his losses, whilst the Georgian government files a token protest. Helena ignores it, but has a furious row with her husband when he returns to Constantinople (after a brief detour to Nicaea). Cheered by the eastern provinces and the army, the Empress does nothing to him, but refuses his request to grant Alexandros Rados, the first eagle-bearer to cross the Euphrates, the Order of the Iron Gates.

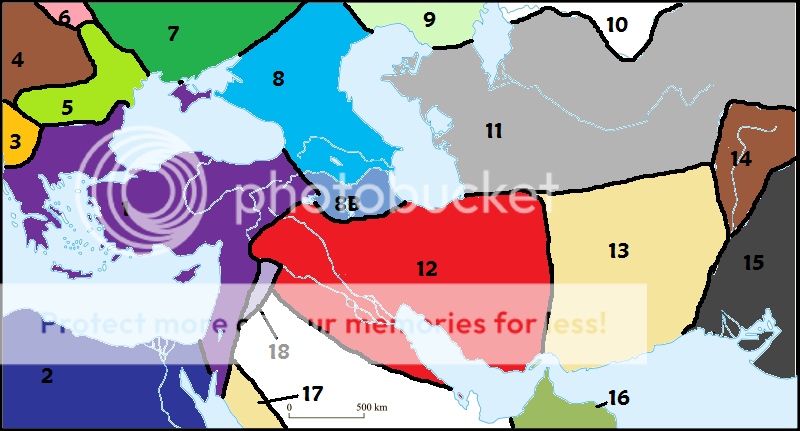

Osman manages to solidify his hold over much of the old Ottoman Empire, but breaking his oath to the peoples of Basra he moves his capital to the more central location of Hamadan, signifying that the Second Ottoman Empire (as historians call it) will be much more Persian than Turkish. But he must acquiesce in the Omani control of Hormuz, the loss of the eastern provinces to Khorasan, and substantial territorial concessions to Georgia as payment for their aid. Meanwhile the Uzbeks overrun all of Transoxiana, ending the Timurid Empire.

In Rhomania, Timur II finds himself an honored guest, but a caged one. His army is lured from his services by Roman gold and girls, their expertise in horse archery highly valued by Roman officers and the War Room. Timur himself is given a gorgeous Roman lady, Maria Laskarina, to wed as a consolation prize for the loss of his power. Still he is a dangerous guest to have, even when he is toothless. On April 10, he dies, although whether by natural causes or by poison is never determined.

But in September, two important births take place in Constantinople. On September 4, the Empress Helena gives birth to a daughter, Christina. Whether the Imperial children are the result of some lingering affection between the couple, Helena’s orders, or simple hate sex is unknown but heavily debated by historians. Two weeks later, Maria Laskarina delivers of a healthy son, Theodoros. For a family name he is given ‘Sideros’, Greek for iron.

Two months later the Empress Helena gives birth to a son, Andreas. The birthing is extremely difficult and painful, with the Empress in labor for a day and a night. Andreas though is healthy, the midwives marveling at his size; according to Theodora at birth he weighed twelve and a half pounds.

The other is the coronation in Kiev of Dmitri I, Great King of the Rus and Grand Prince of Lithuania. Twenty four years old, he is well aware of his purple blood, as he is the great-grandson of Andreas Niketas and Princess Kristina of Novgorod, via their daughter Helena. Prone to sudden mood swings, he is quite vocal about the fact that by blood claim he has a much better right to the throne of Rhomania than its current occupant.

However he, or more properly his advisors, are not crass enough to claim that said throne belongs to Dmitri. The ponderous speed and extreme casualties taken by the Army of the North during the Orthodox War proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that a credible projection of Russian power by land south of the Danube was only possible at an exorbitant price. And at sea, the Roman navy is still almost three times more powerful than the Russian Black Sea, Vlach, and Georgian fleets combined. There is also the matter the Scythia is economically much more inclined to Constantinople than Novgorod, with 2.5 times more exports to Rhomania than to the rest of Russia.

Still, because of his ancestry Dmitri tends to present himself as the leader of Orthodox Christendom, and he toys with the idea of dropping the Roman-bestowed title and crown of Megas Rigas in exchange for a more grandiose title, perhaps ‘Tsar of all the Russias’. But it also difficult for him to break Russian tradition, thus he is unable to commit to either course of action, mainly serving to irritate Constantinople even as in Munich Kaiser Wilhelm solidifies his power by instituting a tour system of his own in Bavaria and Schleswig-Holstein, overseen by Templar administrators.

In Marselha and Avignon on the other hand the main debate is what to do about this new development in Mexico. Although King Basil is irritated that his uncle is insistent on ruling an independent realm he does admit that legally there is no reason for him to expect David to do such a thing. The whole expedition was financed by David personally.

However there is still a way for Basil to benefit from the situation. Emperor David is well aware of the technological backwardness of Mexico compared to the Old World, and equally aware that the few dozen blacksmiths and carpenters in his expedition are nowhere near enough to solve it on their own. His breeding stock for horses is also extremely limited, with inbreeding inevitable considering he only has five healthy stallions.

So the solution is trade. Arles will provide experts and materials, especially swords, armor, cannons, and horses which Mexico cannot make, as well as horses and other livestock (pigs soon become preferred by the Mexicans) in exchange for silver. The bullion mainly comes from the mines of Zacatecas, often worked by captives from the Tarascan war. Although the initial Tarascan invasion was smashed flat in battle by David’s army, he is unable to follow up the advantage due to the diseases ravaging the peoples of Mexico and his need to solidify his hold over his domains.

The Avignon Papacy, under Pope Paul IV, is not nearly so sanguine about the situation, and is disturbed by the lax nature of Mexican Christianity and David’s dilatoriness is fixing the situation. Priests are dispatched across the sea, and while Paul IV does recognize that the true conversion of Mexico will take time, he does expect to see progress to that end. If not, he holds out the possibility of papal approval and support for an Arletian or Portuguese-Castilian expedition. It is a threat David takes very seriously, well aware that there is no rule written that only the first invasion of Mexico can possibly succeed, despite the claims of some of his men who are busily marrying into the Mexican nobility.

In the east, before Sultan-Khan Timur II sweeps south into Mesopotamia, he meets with Princess Theodora on the shores of Lake Van (her two children remain in Constantinople). Their two-week conference is to help set the groundwork for the new order in western Asia. Trade negotiations are formalized and an extradition treaty signed, with both parties swearing eternal friendship. The trade between the two increases, with Timurid horses and astronomy texts flowing west as Timur adds Roman medical treatises to his personal library.

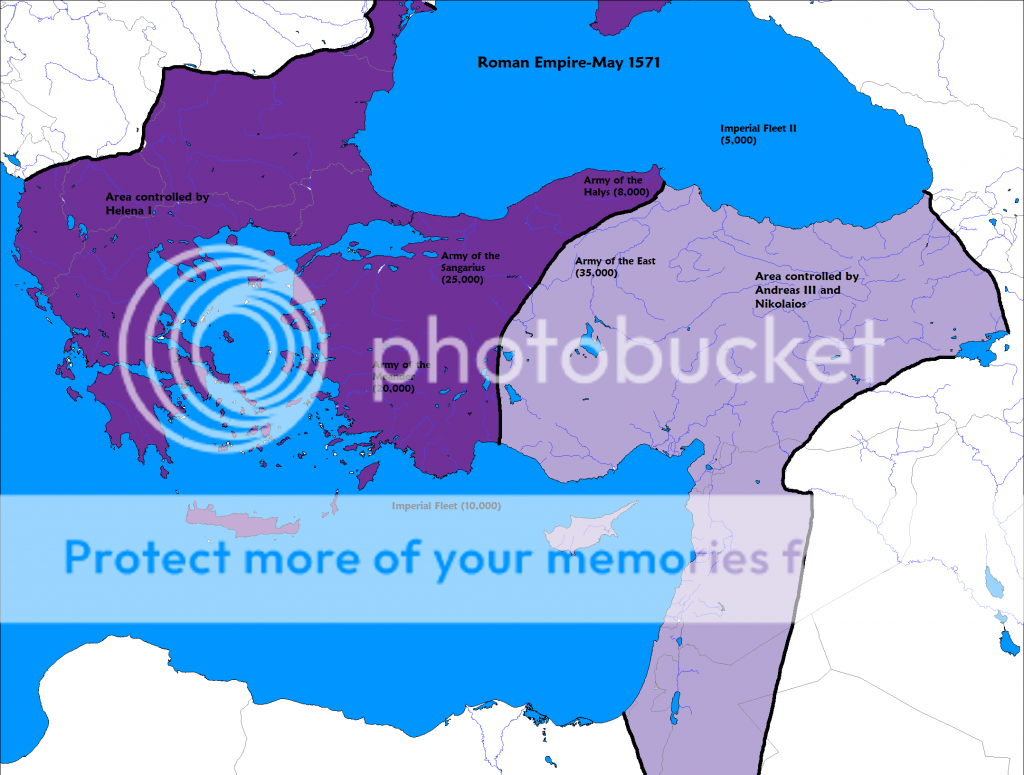

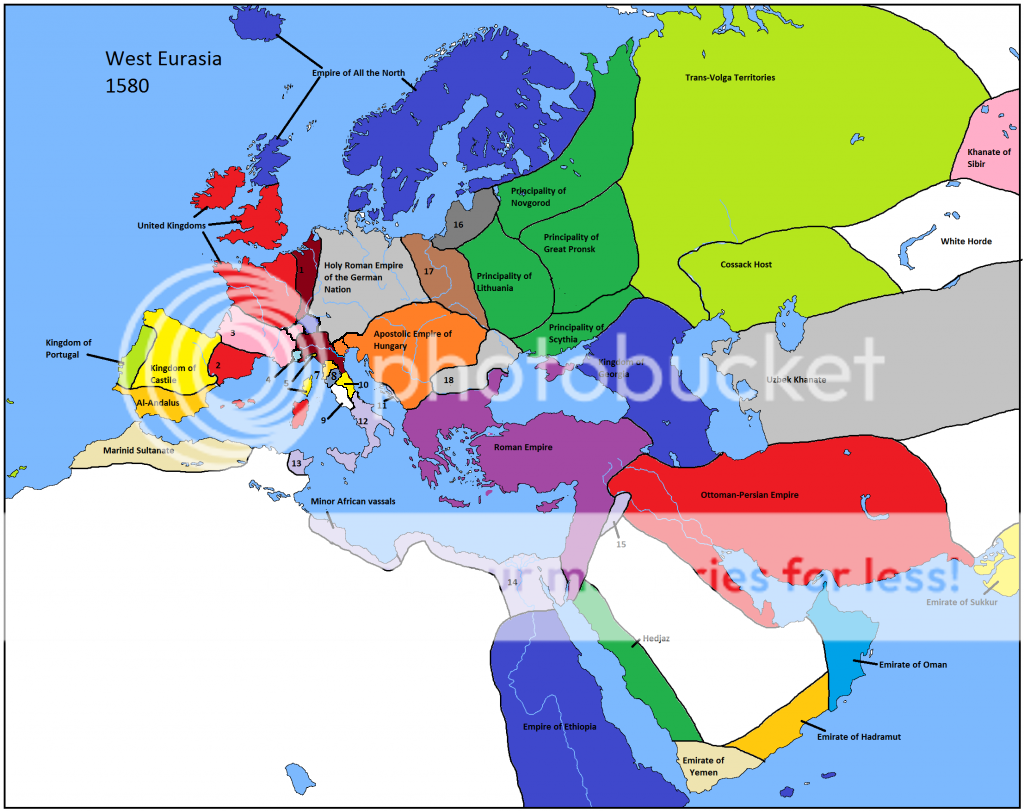

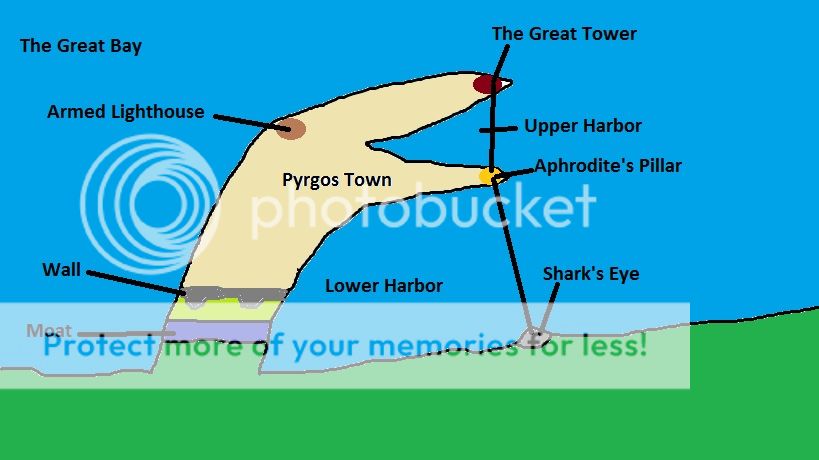

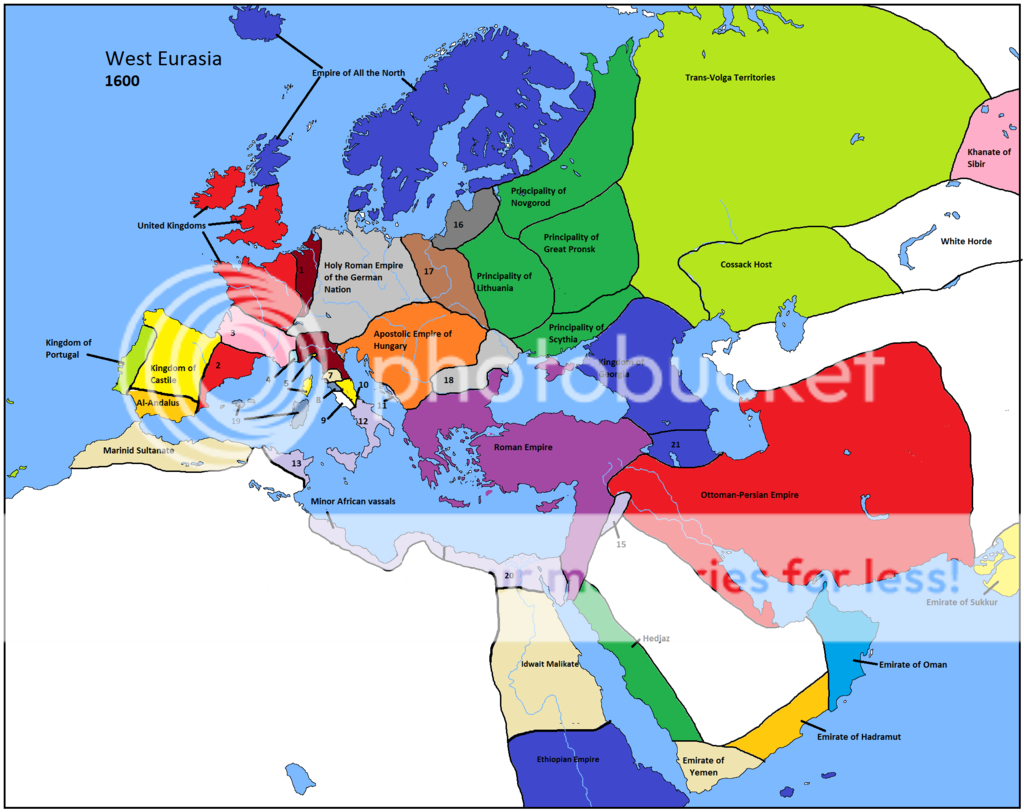

But far more momentous is the Second Treaty of Van. In exchange for an absolutely massive cash payment that wipes out over half of the Roman debt and almost four-fifths of its interest payments (by using the Timurid cash to pay off the higher interest loans early), most of the Roman territory beyond the Euphrates is ceded to the Timurid Empire. At the same time the Anizzah are given autonomous control over much of the remaining Syrian frontier as a Roman vassal (although not as a Despotate), on the grounds that Roman power projection is extremely limited anyway and that it will make the Anizzah defend the area even more fiercely.

Red indicates the land ceded directly to the Timurid Empire. The green is the territory granted to the Anizzah to rule as a vassal-ally of the Empire.

Besides the money, the Treaty pulls the frontier back to a more defensible area in Helena’s eyes. The border is now where it was for most of the fourteenth and fifteenth century, with a much more developed infrastructure and fortress belt, although the latter does need to be modernized. Border defenses can now be more cheaply upgraded by building on the previous Laskarid structures, and better supported thanks to better and more roads and shorter supply lines. Plus it gets rids of another 100,000 Muslims that the Empire doesn’t want, fixing the border amongst more Christian and loyal peoples.

Despite that, the army is utterly outraged by the ceding of a large block of Andreas Niketas’ conquests, and one of the last remaining in Roman hands. Nikolaios Polos, recently promoted to Megas Domestikos, is so livid that after a shouting match with the Empress he storms out of the White Palace. He is gone from the capital for almost four months, coming back only when his wife flat out orders him to return. Also many of the peoples of the east are not happy over the loss of a buffer zone, especially the Edessans, now the terminus for one of the Skopos lines (the one that previously ran to Nisibis; the Palmyra line now ends at Damascus).

As for Timur II, the treaty of Van significantly bolsters his position amongst the inhabitants of Mesopotamia by removing the looming specter of a Roman invasion from them. With a buffer zone between them and the Empire they can sleep easier, and can be expected to be grateful.

Marching south towards Baghdad, he faces little opposition until he actually besieges the Ottoman capital. Sultan Bayezid III has made no attempt to flee, although he has dispatched the treasury and his family to Basra. The defenses of the city have been repaired and improved since Andreas Drakos sacked the metropolis, and the smaller population of forty five thousand is able to defend the city without unduly taxing the stores of supplies.

Thus for three months Bayezid is able to keep Timur out, despite his thirteen batteries of Roman cannon. But on October 11, the city is taken, the Ottoman Sultan killed in battle defending the Topkapi Palace at the head of his few remaining janissaries. Timur keeps the sacking limited to just the eleventh, reproaching a soldier found hacking out pieces of the marble floor of the Topkapi palace, as the buildings belong to him. Entering the Mosque of Osman I, he sprinkles dust on his turban as a gesture of humility, quoting a line from the Iliad:

“The day shall come in which our sacred Troy

And Priam, and the people over whom

Spear-bearing Priam rules, shall perish all.”

In Basra, Bayezid’s eldest child and daughter reacts to the news not with grief but with boldness. In an epic ride across enemy-occupied territory, carrying a fortune in jewels sewn into her and her retainers’ clothing and accoutrements, narrowly avoiding capture on at least three different occasions, she arrives in Sari, the capital of Osman Komnenos. One month to the day after the fall of Baghdad they are wed, her husband formally claiming for the first time the title Shahanshah.

Three days later the Georgian army, under the command of the Grand Domestic Stefanoz Safavi, takes Tabriz, putting every member of the Timurid garrison to the sword.

1553: The sudden and explosive onslaught of the Georgian army comes as a complete surprise to all of its neighbors, including the Romans. Ever since the Orthodox War the Kingdom of Georgia has been a diplomatic non-entity due to its tremendously high losses, and those states bordering it have grown complacent.

It is an understandable mistake, but a bad one, for the force that ushers forth to finally avenge the sack of Baku is the most powerful the Kingdom has put into the field since the days of Thamar the Great three centuries past. The army is a smaller version of the Roman host, but excellently equipped with lamellar armor and gunpowder weapons, although given the terrain of Georgia heavy siege guns are a rarity. Alan light cavalry and Azeri light infantry provide a formidable screen for the heavy troops, of whom pride of place goes to the King’s Immortal Guard.

The areas, besides size, in which the Georgians fall short by Roman standards, is in training and logistics. There is no equivalent to the School of War for officers, although there is an institution for the training of artillerymen and engineers. Nor is there a War Room to organize war plans or march-tables, and Roman quartermasters have little good to say about Georgian logistics (to be fair, that is true for everyone save the Bernese).

Thus Stefanoz Safavi’s sudden riposte that seizes Tabriz stalls after the fall of the city. His ammunition stocks are depleted, rations are short even with Tabriz’s stores, and the winter campaign, although granting the inestimable advantage of surprise, has taken a hard toll in frostbite on men and horses. It is not until May that the army is ready to move again.

The fall of Tabriz severed the main route through which Roman-Timurid trade had been conducted. The Great East Road, linking Chalcedon to Theodosiopolis via Ancyra, plus the Black Sea route to Trebizond (connected via a spur line), had dominated the scene during its brief flowering. Partly that was because of tradition, as when it was established the more southerly routes led to Ottoman territory. But also most of the Roman shipping in the eastern Mediterranean is taking advantage of the oriental routes once again flowing into Egypt, plus the slave trade with Ethiopia.

Still, Timur II already has an impressive stock of Roman armaments to supplement his own manufactures. He marches north, and given the size and skill of his army, there would be every reason to suspect that the Georgians will pay dearly for their audacity.

But Timur II does not face just the Georgians. For Tieh China has once again stirred. Bested in iron, it has turned to gold, and summoned forth a volcano. Ever since its birth, the Kings and later Governors of Urumqi had played a delicate balancing act between the Han and Uyghur elements of the states, with steadily declining success due to Tieh intrigue. In the spring, a full blown Uyghur insurrection erupts, and supported by Chinese gold and arms, obliterates the city of Urumqi, its governor, and his army, ending the two-hundred year old state and replacing it with a Uyghur tribal confederacy under Tieh influence.

With the threat of a two front war against Timurid Samarkand and Urumqi destroyed, the proud Uzbeks, resentful of their long vassalage to the line of Timur, have also begun to move. At their side are the riders of the White Horde, veteran troops bloodied in raids against Russia and the Cossack Host. Together they invade Transoxiana, the heartland of the Timurid Empire. Even the Cossacks join in, although not jointly, supported by a few battalions of Russian regulars shipped down the Volga as Georgian ships basing out of Baku harry the eastern shores of the Caspian.

In the Indian Ocean, the Emirate of Oman has gotten itself into a shooting war with the rising maritime power of the Emirate of Sukkur, which is solidifying its hold over the Punjab and the Rann of Kutch. Already the Kephalate of Surat pays the Emirate a small retainer as protection money. Thus the Omani fleet is unable to stop the counter-attack from Basra which retakes Bahrain, although Hormuz remains firmly in Omani hands.

But the threat of Omani raids is lifted, freeing the garrisons of southern Mesopotamia. They are also reinforced by an influx of Arab riders from the Najd, the losers of a tribal war with the House of Saud, Lords of the Najd and Sharifs of Mecca. No match for the Timurid army in open battles, their pinprick raids are a source of serious annoyance to Timur, disrupting his cultivated persona as protector from the Treaty of Van.

Forced to draw off troops to guard his southern front, contain Osman in Mazandaran, reinforce the defenses of Transoxiana, and guard against a number of Khorasani forays westward, the Georgian and Timurid armies are evenly matched in number when they array for battle at Takab, Stefanoz Safavi placing his command post in the ruins of the ancient fire temple. Timur II is stronger in cavalry, Stefanoz in number of artillery, although the Sultan-Khan has more heavy long-range ordnance.

Going onto the defensive, Stefanoz guards his front with a row of wagons, linked with iron chains which are guarded by cannons and pikes, with gunners firing from behind the barricade. His cavalry is posted in reserve and as flank guards, with a cloud of skirmishers deployed forward. It turns out to be a bit too far forward, as the Timurid horse eviscerate the screen and send it flying back in disarray.

Timur follows up his advantage, charging forward as squadrons curl around the flank as the Georgian ranks are disordered by their backpedaling skirmishers. The center of the Georgian line, held by the King’s Immortal Guard and its fearsome artillery, repels the attack. However the left wing, less stoutly defended and under an attack well supported by Timurid cannonades, is smashed to pieces.

Timur has victory in the palm of his hand, but his troops instead of rolling up the Georgian lines take to plundering his camp. Horse assigned to outflank the Georgians join in the pillaging, freeing three droungoi of Immortal cavalry which Stefanoz personally leads in a counter-charge.

Now it is the Timurids flying back in disarray as all along the line the Georgians counter-attack. Timur commits his reserve, but is struck by a fragment of Georgian shell. Knocked unconscious, he is carried from the field along with his army, which retreats but in good order.

Both sides suffer nearly thirty percent casualties, with historians to this date debating whether it constitutes a Georgian victory or a draw, as the Georgian offensive collapses. But Timur is unable to try for a rematch as rumors of his death encourage the Turks and Arabs of Basra to march north, placing Baghdad under siege.

Timur returns to the city, mauling the Turco-Arab army, and then wheels east to thrash a Khorasani army that had penetrated into the Iranian plateau. Yet though everywhere save Takab he is victorious, everywhere his lieutenants suffer defeat. Osman Komnenos routs the Timurid army facing him, killing its commander, and forges an alliance with the Khorasani with a marriage between the Emir and his second daughter by his first wife (Aisha is his third in number, although first in rank and favor) and payment of subsidies.

With his new allies, Osman seizes the city of Gorgan, on the southeast corner of the Caspian Sea, and shortly afterward establishes control over the ancient Great Wall of Gorgan. Timur is cut off from Transoxiana where the viceroy of Samarkand had nearly won a victory over the Uzbeks, before the tide was turned by the Khan’s bravery, the battle ending in a smashing Timurid defeat.

Retiring westward, Timur knows he must smash at least one of the foes facing him. If he can do that, it will give him the breathing room to turn around and crush the others. In the words of Nikolaios Polos, the Sultan-Khan is ‘a bear beset by a pack of dogs’. Crushing a Georgian contingent near Hamadan, the victory is more than nullified by the news that his rearguard has been cut to pieces by Osman and that Baghdad has fallen by treachery. Shortly afterwards Osman links up with the Turks and Arabs of southern Mesopotamia who pledge loyalty to him as Shahanshah, while he in turn promises to hold true to the traditions and customs of his Ottoman ‘forefathers’.

Timur’s army, worn out by constant battles and marching, is forced to retreat even further west, Osman in pursuit with an army now outnumbering his foe five to two. Still the heir of Timur the Great and Shah Rukh must be feared, as a tremendous backhand blow administered on Osman’s vanguard seriously bloodies it. The pursuit is soon resumed, but it is delayed for a crucial few days. On October 14, Osman appears in full battle array near the ruins of Rakka, known as Kallinikos to the Greeks. On the other side of the Euphrates, guarding the ford, is Nikolaios Polos and the Roman Army of the East. The Shah is six hours late; Timur II and his army have been granted sanctuary in the Roman Empire. All that remains is to cross the river.

Western Bank of the Euphrates, Near Rakka, October 14, 1553:

The sounds of cannon fire was rolling off from the horizon. It was a sound with which Nikolaios Polos was quite familiar. In fact, it was a sound he longed for. He was a soldier; war was what he knew, what he was good at. Peace was not for him. Especially not this peace, he snarled.

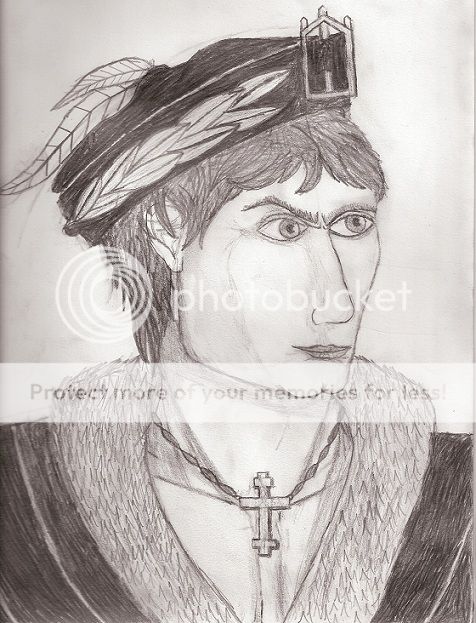

Etching of the Imperial Consort of Empress Helena I Drakina (by Avitus)

-

Helena had had a crush on him since she was fourteen. Nikolaios had never, even when she flowered into womanhood, reciprocated those feelings. But never had he expected that he would come to hate the eldest daughter of the man he regarded as a second father, a man who had treated him like a son.

There was a very good reason why he had not entered the list of suitors vying for the Empress’ hand; he was already engaged at the time.

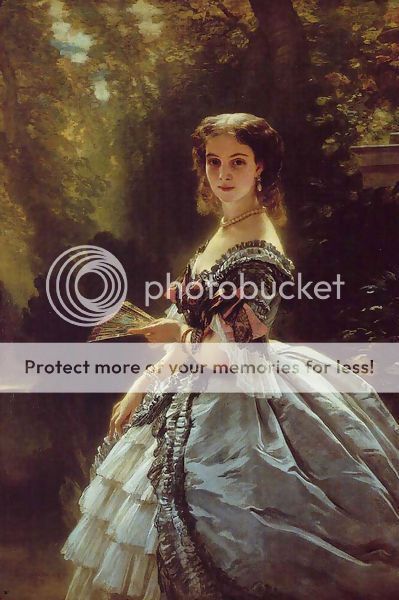

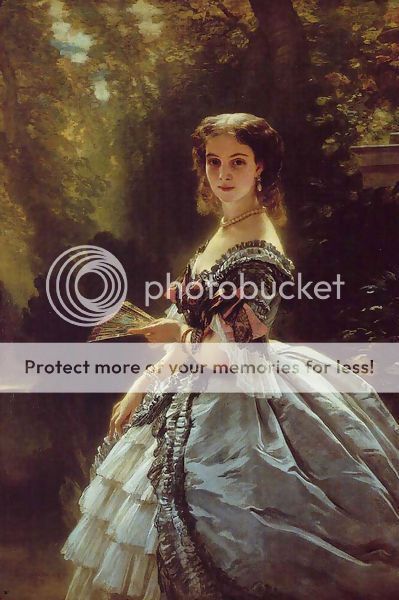

Lady Anna Palaiologina, onetime fiancée to Nikolaios Polos and fifth cousin to Osman Komnenos

-

So he had married Helena Drakina, the most powerful, wealthiest, and acclaimed by many men to be the most beautiful woman in the world. He loathed it. He wasn’t her husband, he was her consort, her breeding stud. He was pretty sure she had listened to him once, on what kind of soup to have with dinner.

Well, that wasn’t true. She listened to him and followed his advice regularly, except that was solely in matters when he was acting as a strategos and she as an Empress. He had no problem with that, but I could have done that and had Anna as well. Bitch.

A spout of water gushed up from the eastern bank of the Euphrates. Timur II was retiring in good order, but he was hounded by Osman’s forces, and a retreat across a narrow ford whilst under attack would be an exceedingly difficult maneuver even for the best of troops. And he was forbidden to engage Osman.

Three more waterspouts leapt up. Save to defend yourself and the Empire. That was his escape clause. He had read the treaty of Van, before using it as toilet paper. The texture had been wrong, but he had still enjoyed it. And the treaty had never specified who owned the Euphrates where it acted as the frontier, so as far as he was concerned Osman was shelling Roman territory.

“Droungarios Michael,” Nikolaios said. “Light the rockets.”

“Yes, sir,” the Cilician Armenian said with a huge grin. Clad in the light gray uniform that was now standard for the Roman army, worn under a burnished steel cuirass, the tall officer bore a large and vicious scar across his left cheek, courtesy of a Turkish scimitar during the siege of Antioch.

He nodded to the Castilian who stood next to the signal rocket batteries. To fill the ranks, foreigners, even Latin ones, had been recruited, provided they learned Greek and followed Roman military discipline. The man took the torch and lit the fuse of a rocket which screamed skyward. The second lit, but sputtered and blew out its bottom, falling to the ground as a tetrachos threw a bucket of water on it. “Misfire,” Michael said.

“Reload.”

Again a rocket shot up into the sky, exploding at about a thousand feet. The second followed this time, and moments later a third joined it.

* * *

“My Sultan!” one of his Keshiks shouted, pointing to the Roman lines. Timur wasn’t sure of what he felt looking at that array. It claimed to be sanctuary, but he had not forgotten that it had been Roman armies that had been the greatest challengers to Shah Rukh and his great namesake.

A white streak of a rocket blazed up and then exploded. Nothing happened. “What does it mean?” one of his officers asked.

Then one after another, three more arced up, shooting toward the sun. “It’s some kind of signal,” Timur said. But what kind? All the rockets were coming from a small promontory on the left bank of the river, one which gave an excellent view of the battlefield and thus a first-rate position for a command post.

For a few seconds nothing happened, and then as one the entire Roman line belched fire, the roar of cannonballs and screams of rockets flying eastward. Is this how it ends? Timur thought. At least it is a mighty end. The terrible projectiles flew, and flew, and flew, and slammed straight into Osman’s left wing. He could hear the screams, even as another fifty rockets leapt out from the Roman lines. Or perhaps not.

* * *

“The batteries will run hot,” Michael said, following his part of the script perfectly.

“Deploy men to ferry water from the rivers.”

“They’ll be exposed to enemy fire.”

“You’re quite right,” Nikolaios replied, scribbling on several pieces of paper. “We will need to guard them. Order the following tourmai to deploy across the river at all speed.”

He handed the forms to Michael. “Yes, sir!” he shouted, whooping as he galloped off to the knot of couriers and scribes deployed a bit to the rear.

It was only ten minutes or so before Nikolaios saw the boats crossing the river as engineers began throwing pontoon bridges together. The equipment had already been positioned for this moment; Nikolaios had no intention of deploying through the ford, not while Timur was attempting to cross it. Battle was no place for a traffic jam.

A few minutes later Michael galloped up. “Droungarios Alexandros, 3rd Syrian, begs to report that the eagle has landed!”

Nikolaios laughed. “Well done, well done.” The gray uniforms had not been the only innovation taken from the Antiochenes, but also the return of the Imperial eagle standards, one for every tourma. He could hear the crackle of arquebus fire as the mauroi let loose on their foes.

He smiled. He had defied the bitch. And perhaps…Nicaea is on the way back to Constantinople…he would do it again.

* * *

For the most part they defended themselves well with arquebus volleys and artillery support from across the Euphrates. Helping them had been some braces of rockets they took with them, and light, pre-made field works and caltrops to cover their position. But even so, Osman’s cavalry charges heavily cut up some formations which had fired too early and been overrun before they could reload. Others had been rescued only by Timurid lancers forming on their flanks in support.

Both owed the other much this day, and had fought side by side as the enraged Osmanli forces stormed across the ford, the Roman bridges blown as the mauroi retired. Timurid and Roman cannons had poured enfilading fire onto the assault columns, a mass charge of Roman kataphraktoi and Timurid lancers sweeping the survivors into the river. The Euphrates, red with blood, was coated in Osmanli dead.

And now it was time to meet his ally, the Megas Domestikos of the Roman Empire, who was waiting for him at his command tent. Timur II smiled as he heard the sounds coming from the Roman camp and sentries, shouting back across the Euphrates. For he spoke Greek, and he clearly recognized the song Do you hear the people sing?

He rode into the Roman camp, flanked by his dirty keshiks, their arms stained by Osmanli blood. The Roman soldiers, similarly stained, looked at him as the Megas Domestikos rode forward, and then took up a new call.

“TIMUR! TIMUR! TIMUR!”

The Megas Domestikos dismounted in front of him and smiled. “Welcome, my lord,” he said. “To Rhomania.”

* * *

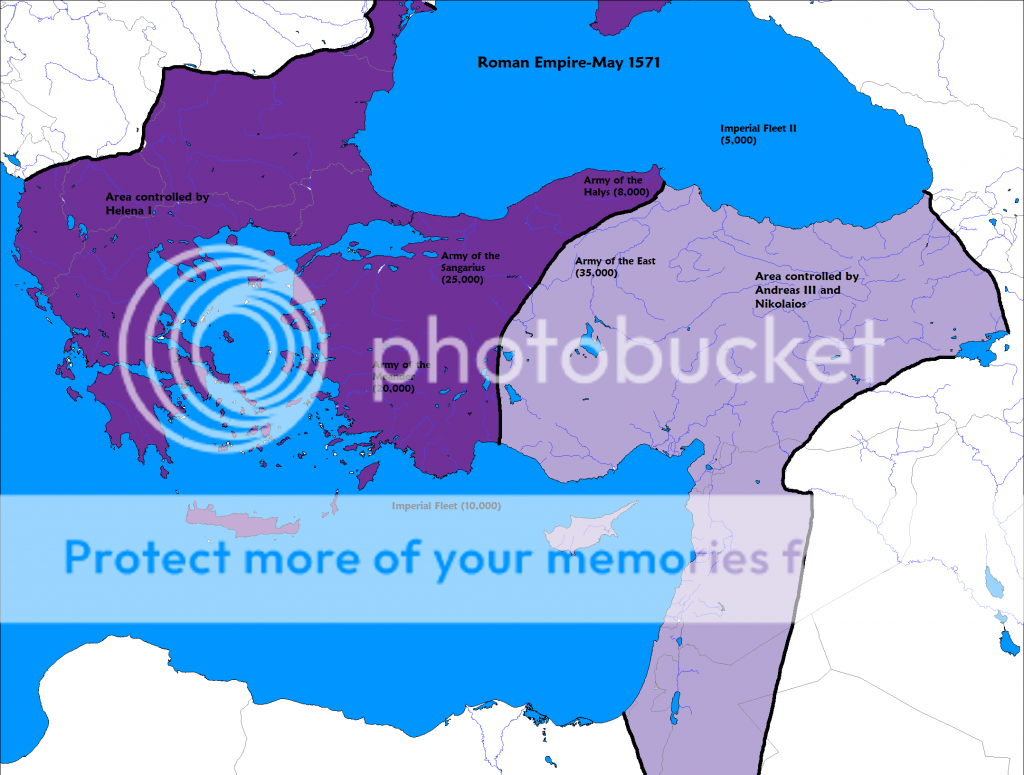

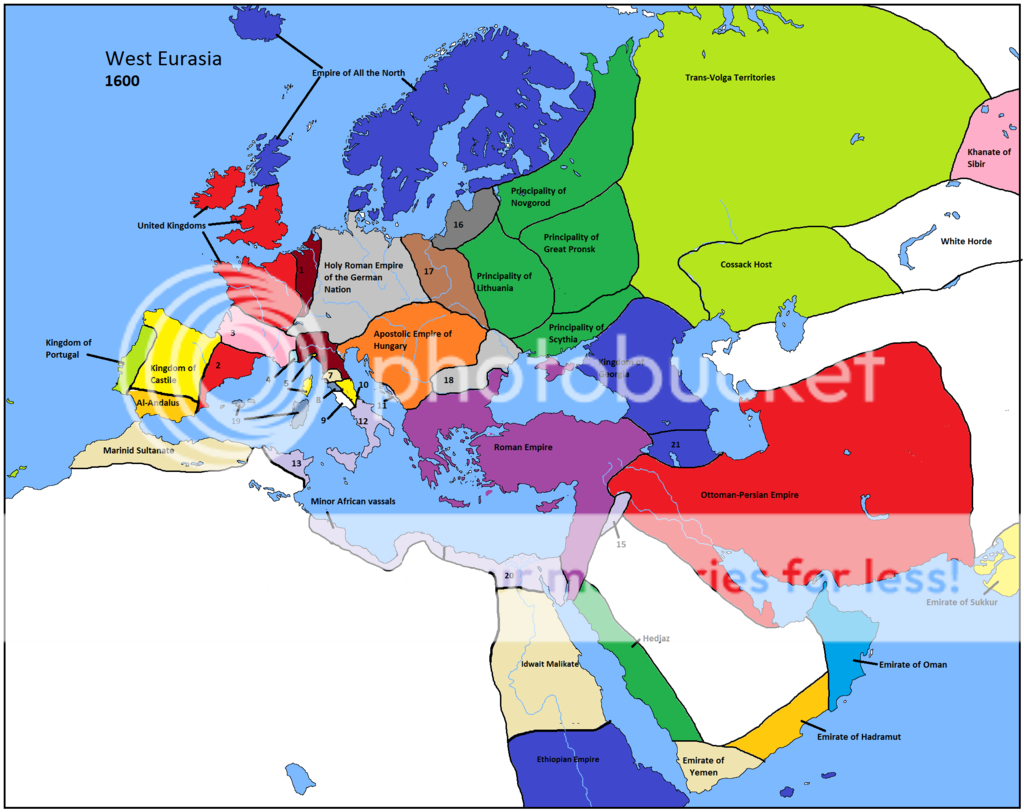

Osman manages to solidify his hold over much of the old Ottoman Empire, but breaking his oath to the peoples of Basra he moves his capital to the more central location of Hamadan, signifying that the Second Ottoman Empire (as historians call it) will be much more Persian than Turkish. But he must acquiesce in the Omani control of Hormuz, the loss of the eastern provinces to Khorasan, and substantial territorial concessions to Georgia as payment for their aid. Meanwhile the Uzbeks overrun all of Transoxiana, ending the Timurid Empire.

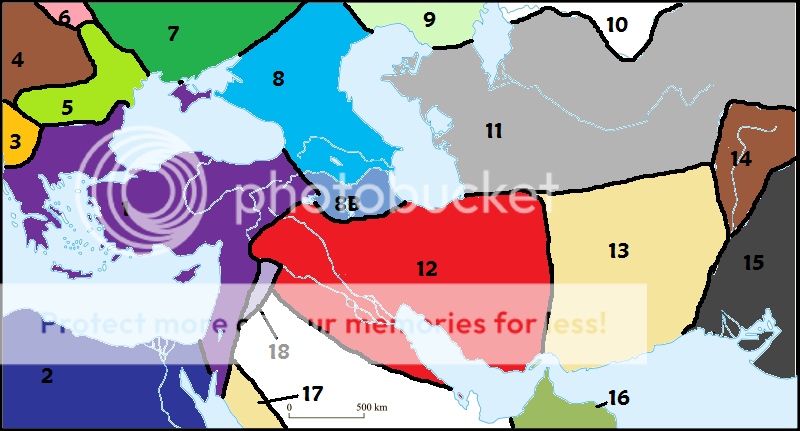

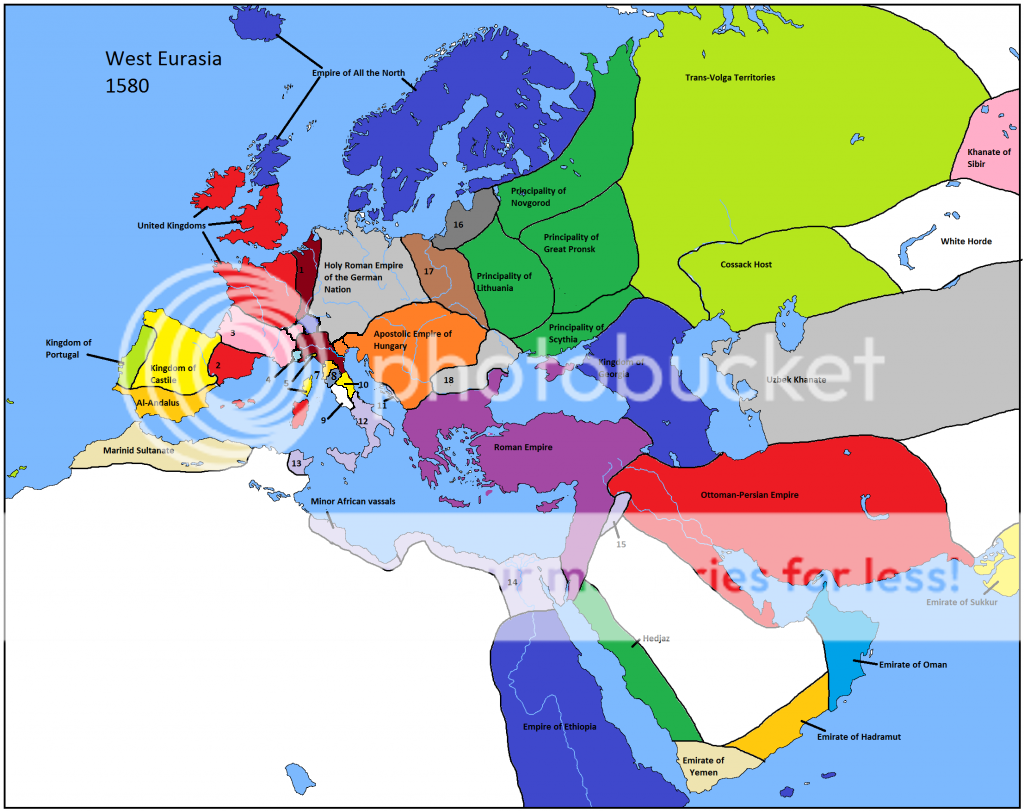

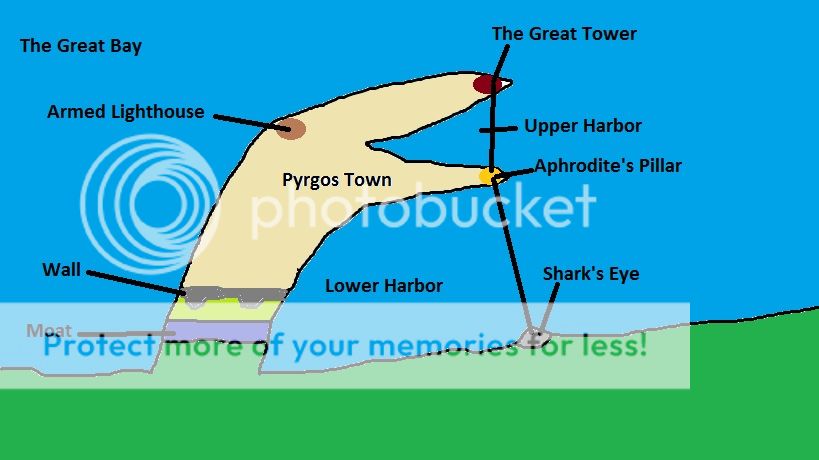

West Asia in 1554

1) Roman Empire

2) Despotate of Egypt

3) Kingdom of Serbia

4) Empire of Hungary

5) Kingdom of Vlachia

6) Kingdom of Poland

7) Great Kingdom of the Rus

8) Kingdom of Georgia, 8B-Georgian territorial gains

9) Cossack Host

10) White Horde

11) Uzbek Khanate

12) Second Ottoman Empire

13) Emirate of Khorasan

14) Punjabi States

15) Emirate of Sukkur

16) Emirate of Oman

17) The Hedjaz

18) Anizzah Confederation

In Rhomania, Timur II finds himself an honored guest, but a caged one. His army is lured from his services by Roman gold and girls, their expertise in horse archery highly valued by Roman officers and the War Room. Timur himself is given a gorgeous Roman lady, Maria Laskarina, to wed as a consolation prize for the loss of his power. Still he is a dangerous guest to have, even when he is toothless. On April 10, he dies, although whether by natural causes or by poison is never determined.

But in September, two important births take place in Constantinople. On September 4, the Empress Helena gives birth to a daughter, Christina. Whether the Imperial children are the result of some lingering affection between the couple, Helena’s orders, or simple hate sex is unknown but heavily debated by historians. Two weeks later, Maria Laskarina delivers of a healthy son, Theodoros. For a family name he is given ‘Sideros’, Greek for iron.

1555: The Empire is quiet, much to the relief of its inhabitants, save for the birth of another baby girl to the Imperial couple, although she only lives for sixteen days. During that time, neither mother nor daughter lay eyes on Nikolaios, who is out in the provinces and makes no move to return to the capital at this time.

Convent of Saint Christina of Acre, three miles east of Nicaea, September 11, 1555:

“Are we there yet?” Andreas asked as Nikolaios led him into the priory library.

“Yes,” he replied, shifting a bit so the sun wasn’t shining through the large, clear, glass window right into his left eye. Surprisingly he did not see any dust motes. The nunnery, named after a martyr killed for sheltering Roman prisoners escaping from Mameluke captivity during the war with Anna I Laskarina, was young, only eighty years old, but obviously that still gave a lot of time for dust to gather. The library was apparently well maintained, and well used too.

Andreas looked around at the shelves of books and the reading chairs and desks. “This is boring. Can we go now?”

“First, there’s someone I’d like to me.”

“Was it the abbess?” Andreas scrunched his face. “She was ugly.”

Nikolaios snorted; his son was right. As owner of the pasture lands where the priory’s flocks of sheep grazed, the abbess couldn’t afford to offend him and thus didn’t prevent his occasional visits to see one of her nuns, but that did not mean she liked them. “No, someone else, someone much prettier.”

“Oh, are they here yet?”

The door opened and she walked in. Her long, elegant hair was gone, her body shrouded in her nun’s habit, but she was still beautiful, far more beautiful than that bitch in all her finery. “Anna,” he said, smiling.

“My tourmarch,” she said, her cheeks dimpling. That was what she had started calling him shortly after they met, in a hospital in Kotyaion just after that battle. She was tending the wounded, a horribly burned eikosarchos to be exact. The man, delirious with pain, thought she was his mother, and to comfort him for the last few minutes of his life, she had been.

“It has been a long time,” he said. Andreas tugged on his coat.

“Five months.” Tug, tug.

Nikolaios looked down. “What?”

Andreas stared at him, eyes wide. “You’re supposed to be paying attention to me.”

“This must be your son,” Anna said, walking forward and squatting down in front of him. “I’ve heard so many things about you, most of them good.” She glanced at Nikolaios, her eyes twinkling and her lip curling up a bit on the right. “Surprising considering your father. You look much like him.” That was certainly true; physically Andreas took entirely after Nikolaios’ side of the family. Just like Nikolaios’ father, Andreas at age three was the height of boys twice his age. The only sign of his Drakid heritage was his slight double chin, a feature not of his mother, but of his grandfather Andreas II Drakos.

“Dad is right,” Andreas said. “You are pretty, like mother.” Nikolaios frowned, she should be your mother.

Anna may have sensed that, may have thought the same thing. “Well, thank you,” she said. She stood up, pulling a small packet from a pocket. Do nuns’ clothes normally have pockets? Nikolaios thought. Well, a lot of them have shifts as shepherdesses. “I have a little treat for you,” she continued, unwrapping the contents to reveal a light brown bar.

“What is it?” Nikolaios asked.

“It’s a new thing, made from Cyprus sugar and a plant from the New World. It’s called chocolate.”

1556: As Alexeia gives birth to a son, her first living child (she had a stillborn eighteen months earlier), her half-sister Theodora is in Sicily, the first stop in her grand diplomatic tour of Europe to improve Rhomania’s relations with the western powers. There she makes history as the first woman to attend the Despot of Sicily, her distant cousin, at the Commemoration of the Martyrs in Senise.

The Commemoration, begun a year after the end of the Great War, has become a central focus of the Sicilians. At Senise, the sacred, holy fire is kept constantly burning, attended by three men, a Catholic, an Orthodox, and a Jew. Every year, on the anniversary of the martyrdom of Senise, the Despot and twelve attendants feed 1,739 logs into the fire, the accepted number of those who killed themselves on that day.

The symbolism of the Holy Fire is everywhere apparent in Sicily, deliberately encouraged by the House di Lecce-Komnenos to unite their young realm into a cohesive, distinct whole. The banner of the despotate shows a phoenix arising from a bonfire, clutching three swords in its talons. The Holy Fire at Senise is always to be lit, save for the time of war, at which time it is to be doused ‘so that the spirit of the Holy Fire may go out into the peoples of Sicily, so that through them and by them fire will purify.’

Next Theodora travels to Carthage where she spends the winter, giving birth to twins, a boy and girl. The main topic of discussion between the Empire and its most independent despotate are the Barbary corsairs, which continue to be a major problem. There have been the occasional raid against Sicilian shores, and joint operations between Carthaginian, Sicilian, and Roman vessels on the open seas have proven ineffective. The corsairs merely stay in port until the squadrons leave the area.

To help in the effort, logistical arrangements are made for Carthage to support twelve Roman monores, light oared warships armed with a few guns. Also the city is to provide grain, wine, and oranges to feed the Maltese squadron which is being reinforced, including the new sixty-seven gun great dromon Alexios Komnenos. At the same time, to further Carthaginian diplomatic endeavors, Theodora personally invests several of the most prominent local sheiks allied with Carthage with silken robes and golden chains.

The Kingdom of Aragon takes a more drastic measure to bolster its security. In exchange for a yearly tribute of a hunting falcon, an Arab stallion, and thirty five pounds of pepper, the island of Minorca is ceded to the Knights Hospitaler on condition they help safeguard the Mediterranean against the ‘African heathen’ (note the use of the term African, which deliberately excludes the Andalusi, Aragonese allies in the war against the corsairs).

With numerous estates and revenues from the lands that follow the Avignon Papacy, plus moneys paid to them by the Roman government for their function in policing Syria and keeping the Muslims in line, the Order is quite wealthy. Seeing a way to expand Roman influence into the western Mediterranean on the coattails of the Knights, Helena provides masons, carpenters, and blacksmiths, plus building materials to help construct the Hospitaler fortresses on Minorca.

1557: The expansion of Roman influence in the east is far less subtle, for a variety of reasons. While peace is desired above all else in the Imperial heartland, in the east can be heard the constant sound of Roman cannon fire. One explanation is that while constant drill is good for improving soldiery, nothing can compare to the support of veteran cadres.

Thus there is the constant dispatching of several droungoi every year to the eastern provinces to gain combat experience. Fighting on the coast, in towns or villages, or at sea, these types of battle favor either light infantry or dismounted cavalry as opposed to the sarissophoroi which are kept home, a move that further lessens their prestige. The idea is that a few droungoi from every light infantry or cavalry tourmai will spend three or four years in the east, returning home to serve as a veteran cadre for their unseasoned-by-battle compatriots.

Coupled with the maturation of the Roman shipyards in Taprobane and the factories in Pahang, this majorly boosts the military power available to Rhomania in the east. That said, more important for Roman success in Indonesia (where much of the aggression is spent) is the recent collapse of Majapahit power due to internal court intrigues and vassal breakaways. There is no significant power able to keep the Romans out, although the Sultanate of Brunei is a serious annoyance.

Both Tidore and Ternate are ‘convinced’ to become Roman trading partners, trading cloves for Roman textiles, metalware, and pocket watches (a new export). However there is a considerable push to remain on good terms with the locals, so the trade deals are arranged to be profitable for both sides, even if it is more profitable for the Romans. No garrisons are posted on the islands, nor any attempt made to interfere in local affairs. The Romans are interested in anchorages and cloves, nothing more.

Although dramatic, the raids on Halmahera, in retaliation for the head-hunting cannibalistic natives’ attacks on grounded ships, are of little historical significance save for keeping the inhabitants of neighboring Tidore and Ternate honest. Far different is the conquest of Ambon. With a magnificent deep-water harbor, the island immediately becomes the base of Roman operations in the Moluccas, the town of New Constantinople getting a bishop just a year after its founding.

The Greek Orthodox Church in the east is under the control of the Metropolitan of Colombo, who reports directly to the Patriarch of Constantinople (Alexandria originally had claim to the sees, but forfeited them in Roman eyes by the Egyptians’ revolt). Under him are the Bishops of Surat, Jaffna, and the Moluccas, with an array of parish priests scattered from Zanzibar to Nan ministering to Roman merchants.

Patriarch Matthaios II is extremely interested in proselytizing in the east, both for religious purposes, but also as a way to invigorate and strengthen the Empire, ‘the ship which carries the faithful’. Besides the monetary gains (the Patriarch plus a dozen metropolitans and bishops are shareholders in three merchant companies operating in the Indian Ocean), Matthaios envisages the creation of a vast Orthodox host in the east, perfect for waging a second front against the Persians. Also to that end he heavily favors an Ethiopian alliance.

Two of those merchant companies operate in Tondo, rapidly developing into a thriving port frequented by Romans, Ethiopians, Japanese, and Wu, all waxing rich from a single thing, piracy. Week after week, wokou descend onto the shores of China, drawn from all four peoples. Here is where most of the eastern droungoi gain their battle scars, leaping onto beaches from Liaodong to Hainan with kyzikos and saber.

At first glance it seems odd that Rhomania would fear the power of Brunei but scorn that of China. But Rhomania in the East is a sea power, and Tieh China has long since lost its sea legs, delegating its naval defense to its vassals Korea and Champa, both of which are rather apathetic about the duty. Champa in fact is becoming quite cozy with the Romans and Ethiopians due to Vijaya’s intense rivalry, bubbling into open war as the year ends, with Ayutthaya, Portugal’s primary ally in the east.

Regardless of what one thinks of their morality, no one can question the bravery and stamina of the ‘thieves and beggars’, as the Tieh court disdainfully call the various foreign wokou. Last year, a joint Japanese-Roman squadron took the city of Shanghai, taking away loot valued at almost three fifths the annual revenue of the Kingdom of England.

This year the prize is even greater, as an immense host drawn from the eastern Romans, a handful of Ethiopian vessels, four of the black ships of Wu, and the assembled armada of Satsuma capture Hangzhou, the third largest city in all the Tieh domain. There is no way the city can be held for long, although the first Wei troops to arrive on the scene are quickly routed, but the plunder is equivalent to the annual revenues of the Holy Roman Empire, France, and Castile combined.

This year the prize is even greater, as an immense host drawn from the eastern Romans, a handful of Ethiopian vessels, four of the black ships of Wu, and the assembled armada of Satsuma capture Hangzhou, the third largest city in all the Tieh domain. There is no way the city can be held for long, although the first Wei troops to arrive on the scene are quickly routed, but the plunder is equivalent to the annual revenues of the Holy Roman Empire, France, and Castile combined.

More importantly for the future though is that on December 1, in the Pagoda of the Six Harmonies, rechristened as Aghia Sophia, Shimazu Tadatsune, head of the Shimazu clan, daimyo of Satsuma, Osumi, and Hyuga, suzerain of the vassal Ryukyu kingdom, converts to Greek Orthodoxy.

* * *

“Are we there yet?” Andreas asked as Nikolaios led him into the priory library.

“Yes,” he replied, shifting a bit so the sun wasn’t shining through the large, clear, glass window right into his left eye. Surprisingly he did not see any dust motes. The nunnery, named after a martyr killed for sheltering Roman prisoners escaping from Mameluke captivity during the war with Anna I Laskarina, was young, only eighty years old, but obviously that still gave a lot of time for dust to gather. The library was apparently well maintained, and well used too.

Andreas looked around at the shelves of books and the reading chairs and desks. “This is boring. Can we go now?”

“First, there’s someone I’d like to me.”

“Was it the abbess?” Andreas scrunched his face. “She was ugly.”

Nikolaios snorted; his son was right. As owner of the pasture lands where the priory’s flocks of sheep grazed, the abbess couldn’t afford to offend him and thus didn’t prevent his occasional visits to see one of her nuns, but that did not mean she liked them. “No, someone else, someone much prettier.”

“Oh, are they here yet?”

The door opened and she walked in. Her long, elegant hair was gone, her body shrouded in her nun’s habit, but she was still beautiful, far more beautiful than that bitch in all her finery. “Anna,” he said, smiling.

“My tourmarch,” she said, her cheeks dimpling. That was what she had started calling him shortly after they met, in a hospital in Kotyaion just after that battle. She was tending the wounded, a horribly burned eikosarchos to be exact. The man, delirious with pain, thought she was his mother, and to comfort him for the last few minutes of his life, she had been.

“It has been a long time,” he said. Andreas tugged on his coat.

“Five months.” Tug, tug.

Nikolaios looked down. “What?”

Andreas stared at him, eyes wide. “You’re supposed to be paying attention to me.”

“This must be your son,” Anna said, walking forward and squatting down in front of him. “I’ve heard so many things about you, most of them good.” She glanced at Nikolaios, her eyes twinkling and her lip curling up a bit on the right. “Surprising considering your father. You look much like him.” That was certainly true; physically Andreas took entirely after Nikolaios’ side of the family. Just like Nikolaios’ father, Andreas at age three was the height of boys twice his age. The only sign of his Drakid heritage was his slight double chin, a feature not of his mother, but of his grandfather Andreas II Drakos.

“Dad is right,” Andreas said. “You are pretty, like mother.” Nikolaios frowned, she should be your mother.

Anna may have sensed that, may have thought the same thing. “Well, thank you,” she said. She stood up, pulling a small packet from a pocket. Do nuns’ clothes normally have pockets? Nikolaios thought. Well, a lot of them have shifts as shepherdesses. “I have a little treat for you,” she continued, unwrapping the contents to reveal a light brown bar.

“What is it?” Nikolaios asked.

“It’s a new thing, made from Cyprus sugar and a plant from the New World. It’s called chocolate.”

* * *

Her Serene Highness, Theodora Laskarina Komnena Drakina. Viewed by many, both contemporaries and future generations, as the smartest and most learned of the Triumvirate, Theodora is also distinguished by having the most stable and loving family life. In the opinion of Professor Kalekas, foremost expert on the early Fifth Empire, it is the best in all-around Imperial familial relations since the days of Theodoros IV and Helena Doukina.

Image taken from The Fifth Empire, Ep. 4 ‘Peace in the West’

The Commemoration, begun a year after the end of the Great War, has become a central focus of the Sicilians. At Senise, the sacred, holy fire is kept constantly burning, attended by three men, a Catholic, an Orthodox, and a Jew. Every year, on the anniversary of the martyrdom of Senise, the Despot and twelve attendants feed 1,739 logs into the fire, the accepted number of those who killed themselves on that day.

The symbolism of the Holy Fire is everywhere apparent in Sicily, deliberately encouraged by the House di Lecce-Komnenos to unite their young realm into a cohesive, distinct whole. The banner of the despotate shows a phoenix arising from a bonfire, clutching three swords in its talons. The Holy Fire at Senise is always to be lit, save for the time of war, at which time it is to be doused ‘so that the spirit of the Holy Fire may go out into the peoples of Sicily, so that through them and by them fire will purify.’

Next Theodora travels to Carthage where she spends the winter, giving birth to twins, a boy and girl. The main topic of discussion between the Empire and its most independent despotate are the Barbary corsairs, which continue to be a major problem. There have been the occasional raid against Sicilian shores, and joint operations between Carthaginian, Sicilian, and Roman vessels on the open seas have proven ineffective. The corsairs merely stay in port until the squadrons leave the area.

To help in the effort, logistical arrangements are made for Carthage to support twelve Roman monores, light oared warships armed with a few guns. Also the city is to provide grain, wine, and oranges to feed the Maltese squadron which is being reinforced, including the new sixty-seven gun great dromon Alexios Komnenos. At the same time, to further Carthaginian diplomatic endeavors, Theodora personally invests several of the most prominent local sheiks allied with Carthage with silken robes and golden chains.

The Kingdom of Aragon takes a more drastic measure to bolster its security. In exchange for a yearly tribute of a hunting falcon, an Arab stallion, and thirty five pounds of pepper, the island of Minorca is ceded to the Knights Hospitaler on condition they help safeguard the Mediterranean against the ‘African heathen’ (note the use of the term African, which deliberately excludes the Andalusi, Aragonese allies in the war against the corsairs).

With numerous estates and revenues from the lands that follow the Avignon Papacy, plus moneys paid to them by the Roman government for their function in policing Syria and keeping the Muslims in line, the Order is quite wealthy. Seeing a way to expand Roman influence into the western Mediterranean on the coattails of the Knights, Helena provides masons, carpenters, and blacksmiths, plus building materials to help construct the Hospitaler fortresses on Minorca.

1557: The expansion of Roman influence in the east is far less subtle, for a variety of reasons. While peace is desired above all else in the Imperial heartland, in the east can be heard the constant sound of Roman cannon fire. One explanation is that while constant drill is good for improving soldiery, nothing can compare to the support of veteran cadres.

Thus there is the constant dispatching of several droungoi every year to the eastern provinces to gain combat experience. Fighting on the coast, in towns or villages, or at sea, these types of battle favor either light infantry or dismounted cavalry as opposed to the sarissophoroi which are kept home, a move that further lessens their prestige. The idea is that a few droungoi from every light infantry or cavalry tourmai will spend three or four years in the east, returning home to serve as a veteran cadre for their unseasoned-by-battle compatriots.

Coupled with the maturation of the Roman shipyards in Taprobane and the factories in Pahang, this majorly boosts the military power available to Rhomania in the east. That said, more important for Roman success in Indonesia (where much of the aggression is spent) is the recent collapse of Majapahit power due to internal court intrigues and vassal breakaways. There is no significant power able to keep the Romans out, although the Sultanate of Brunei is a serious annoyance.

Both Tidore and Ternate are ‘convinced’ to become Roman trading partners, trading cloves for Roman textiles, metalware, and pocket watches (a new export). However there is a considerable push to remain on good terms with the locals, so the trade deals are arranged to be profitable for both sides, even if it is more profitable for the Romans. No garrisons are posted on the islands, nor any attempt made to interfere in local affairs. The Romans are interested in anchorages and cloves, nothing more.

Although dramatic, the raids on Halmahera, in retaliation for the head-hunting cannibalistic natives’ attacks on grounded ships, are of little historical significance save for keeping the inhabitants of neighboring Tidore and Ternate honest. Far different is the conquest of Ambon. With a magnificent deep-water harbor, the island immediately becomes the base of Roman operations in the Moluccas, the town of New Constantinople getting a bishop just a year after its founding.