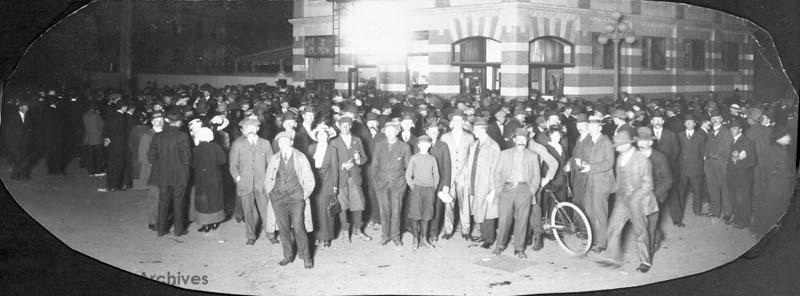

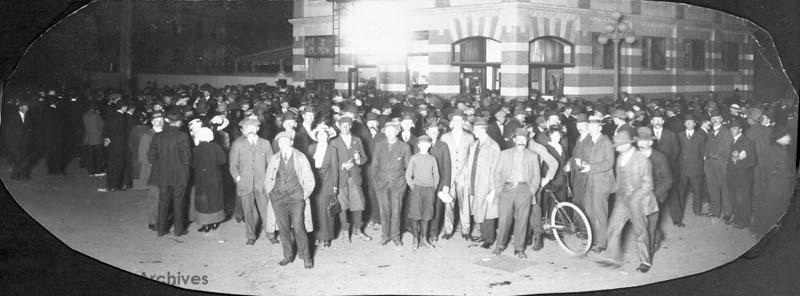

Piles of broken glass

Aug 19, 0700 hours. Victoria.

The mayor had read the Riot Act at midnight, standing on the back of Tiger Company’s hook and ladder truck, at the corner of Blanshard and Johnson Streets. By first light, the anti-German mobs had long ago gone home. A few were sleeping off their hangovers in the City Gaol. By 7:00 AM street sweepers were making piles of broken glass outside the Krieghoff Hotel. The proprietor stood on the sidewalk, holding a raw steak to his right eye, and shaking his head in disbelief.

“What are we to do?” he asked no one in particular. “Where are we to go?”

Two men made rude expressions at him as they carried a red velvet couch out the door and down the street. Crowds were thinner now, and made mostly of gawkers.

The scene was much the same outside Carl Lowenburg Men’s Furnishings on Wharf Street, and Simon Leiser and Company on Yates Street, Moses Lenz Wholesale Merchants, the former German Consulate, and the German Club. All glass within reach was broken, and merchandise looted or dragged out into the street. The rioting had started before dark at the Kreighoff Hotel, ostensibly in response to the rumour of a party celebrating the German victory at Prince Rupert. Then the violence and looting had accelerated, fueled by the contents of the Krieghoff and German Club bars. The police and fire department drew the line at arson, and had hosed down the crowd on a couple of occasions when small fires were lit. The mob was itself in disagreement on the use of fire, knowing that non-German establishments were cheek by jowl with German-Canadian businesses. Some brawls had broken out within its ranks.

In Chinatown, all stores were bolted and shuttered, but residents did not sleep a wink, fearing that the mob would not satiate themselves on their German neighbors and would come looking for more premises to smash. As it turned out, their fears did not come true this time.

The militia, under direction of the Premier and Colonel Roy, had declined a desperate call from the Victoria Police chief to intervene, so law enforcement had been stretched thin. The militia had cancelled all leave however, which drew down the anti-German numbers on the street for any subsequent night’s activities.

“Rioters Wreck City Premises” said the Headline of the Daily Colonist. “Mob, in Anti-German Demonstration, Does Damage Estimated at $20,000—Police are Powerless.”

Other headlines read: “German Cruiser Nürnberg ravages North Coast. Prince Rupert, Ocean Falls, Anyox, Swanson Bay shelled.” “Coastal Steamship Service Disrupted. GTP, CPR, and Union Steamship Lines report ships captured or missing—details still unclear.” “War Comes to Ketchikan,” followed by a reprint of the Ketchikan Daily Miner Story. The residents of Victoria had their worst fears confirmed, although not many were by this point surprised.

Interspersed with these alarming headlines were stories of a different kind: “Esquimalt Coastal Artillery Practice Fires Today—Defence of Capital Certain.”

“Militia Deploying Overwhelming Force to Resist Any Possible Landing.” “Premier McBride to Give Speech at Legislature at Noon on State of the Province’s Defences.”

Photos from City of Victoria Archives.

The mayor had read the Riot Act at midnight, standing on the back of Tiger Company’s hook and ladder truck, at the corner of Blanshard and Johnson Streets. By first light, the anti-German mobs had long ago gone home. A few were sleeping off their hangovers in the City Gaol. By 7:00 AM street sweepers were making piles of broken glass outside the Krieghoff Hotel. The proprietor stood on the sidewalk, holding a raw steak to his right eye, and shaking his head in disbelief.

“What are we to do?” he asked no one in particular. “Where are we to go?”

Two men made rude expressions at him as they carried a red velvet couch out the door and down the street. Crowds were thinner now, and made mostly of gawkers.

The scene was much the same outside Carl Lowenburg Men’s Furnishings on Wharf Street, and Simon Leiser and Company on Yates Street, Moses Lenz Wholesale Merchants, the former German Consulate, and the German Club. All glass within reach was broken, and merchandise looted or dragged out into the street. The rioting had started before dark at the Kreighoff Hotel, ostensibly in response to the rumour of a party celebrating the German victory at Prince Rupert. Then the violence and looting had accelerated, fueled by the contents of the Krieghoff and German Club bars. The police and fire department drew the line at arson, and had hosed down the crowd on a couple of occasions when small fires were lit. The mob was itself in disagreement on the use of fire, knowing that non-German establishments were cheek by jowl with German-Canadian businesses. Some brawls had broken out within its ranks.

In Chinatown, all stores were bolted and shuttered, but residents did not sleep a wink, fearing that the mob would not satiate themselves on their German neighbors and would come looking for more premises to smash. As it turned out, their fears did not come true this time.

The militia, under direction of the Premier and Colonel Roy, had declined a desperate call from the Victoria Police chief to intervene, so law enforcement had been stretched thin. The militia had cancelled all leave however, which drew down the anti-German numbers on the street for any subsequent night’s activities.

“Rioters Wreck City Premises” said the Headline of the Daily Colonist. “Mob, in Anti-German Demonstration, Does Damage Estimated at $20,000—Police are Powerless.”

Other headlines read: “German Cruiser Nürnberg ravages North Coast. Prince Rupert, Ocean Falls, Anyox, Swanson Bay shelled.” “Coastal Steamship Service Disrupted. GTP, CPR, and Union Steamship Lines report ships captured or missing—details still unclear.” “War Comes to Ketchikan,” followed by a reprint of the Ketchikan Daily Miner Story. The residents of Victoria had their worst fears confirmed, although not many were by this point surprised.

Interspersed with these alarming headlines were stories of a different kind: “Esquimalt Coastal Artillery Practice Fires Today—Defence of Capital Certain.”

“Militia Deploying Overwhelming Force to Resist Any Possible Landing.” “Premier McBride to Give Speech at Legislature at Noon on State of the Province’s Defences.”

Photos from City of Victoria Archives.