I, VI: The Grand National Holiday & Provincial Charters

On February 18th, as a meeting of Quakers at a Friends Meeting Hall in Liverpool was violently broken up by Yeomanry, leaving 6 men dead and the Meeting Hall burned to the ground, Wellington privately called upon Eldon to make an example of the Yeoman involved, the Cheshire and Warrington Yeomanry, but Eldon refused. Later that day, he tendered his resignation to the Regent, leaving Eldon in charge. In the North, the Regent became known as

Vicious Victoria. While the opinion of the Queen, young Victoria, was still held in high regard, her mother and Conroy was felt to be toxic to the constitution. Conroy in particular, as Lord President of the secret Privy Council meetings, was in line for significant criticism. Britons across the islands desired for better government: commercial classes wanted competent economic policy and a reduction in the national debt, agricultural workers wanted either their share of land (in Scotland, Ireland, Wales and the Swing Counties) or protection from enclosures (in the ever-Industrialising North), workers wanted the vote, better wages and conditions and the Liberal Nobles had grown weary of the constant militarism and incompetency that they were too exacerbated to protest at the traditional order. Even in the military, some questions arose, like "We swear loyalty to the Queen, do we need to listen to her Regent?", as one soldier interviewed in the Political Register said in an investigation on radicalism in the Army. The officer corps, continually loyal throughout the ages, did not feel the need to submit to an unpopular Regent and in Conroy, a promiscuous prat, especially when murdering innocent workers in cities, rather than international conquest, occupied the majority of their terms between 1829-1832. Loyalty had wavered.

While the violence in the South began to mellow throughout March, the weather improved briefly and protesters began to re-emerge and the reinforcement of P.O.R.A by domestic forces became lethargic. Removing Wellington collapsed support within the Officer corps, Eldon was seen as a cruel and old-fashioned Minister with far too much power. This third wave of protest, bigger and more public demonstrations saw more resigned enforcement of officers and yeomen, as the growing ranks, including more and more liberal-leaning nobles, who wished to vote to remove the Wellington Ministry, meant that they were often attacking neighbours, friends and family. A Tory Member of Parliament, George Child Villiers, noted that "The enforcement of the law became a farce in the spring, as men refused to shoot on their own. An attempt to switch enforcement out of town, and use Yeomanry to suppress Sedition, was met with equal lethargy. One officer who lost his troop found them sat, discussing the aims of the meeting with a speaker." As economic depression took hold and the long-term effects of the full transition from cottage economy, to the largest wartime economy until the 1900s, to an industrial economy in the space of 30 years became stronger, strangled further by the Corn Laws, which made Bread Riots a regular occurrence throughout March in areas without martial law. High Sheriff of Leicestershire, a relative county of peace throughout the riots across the country, George J.D.B Danvers said on March 1831 wrote in his diary "many of the reliable actions of state have become worrisome... there is talk of the Yeomen running out on the Grand National Holiday on mass".

In the north, however, the repression had been sent into a spiral. By breaking up the spirits in the North, Eldon argued, a more 'compliant' peoples would become ready for reform. Eldon had used his time as Home Secretary to recall transported criminals from the colonies to form squadrons to 'remove' Radical leaders. A Radical Speaker, John Denton, was brutally beaten in the street and hung from a cross by one of these squadrons, who arrived first in February and were stationed, usually, as Eldon described them, as "packs" throughout major industrial cities. Any resistance and help would be treated as treason, although the gangs would usually ensure there were few survivors. In Hull, 6 men were bayoneted in a liberal-leaning debating society, in Liverpool, a distillery hosting a radical speaker was burned down, killing the speaker, Thomas Bish and the family of 13 who lived and worked there. In the press, sympathy moved slowly to the idea of armed agitation, as noted by Henry Hunt's admission on April 5th that a speech that "in the north, Her Majesties Government has turned its criminals, its military might and its bayonets on workers that are asking for the vote. Men have been killed in greater numbers and in such prolonged time and, understandably, individuals may want to protect themselves and their families. No liberty, no representation and no freedom is not the tonic for tranquillity." In Rochdale, military drills had been held for weeks now, in the moors in East Lancashire, often practising with experienced cells, of over two months of preparation themselves, from Yorkshire. One member, Theodore "Teddy" Smythwaite, who drilled with the groups in April said:

"The discipline brought by officers, who were usually those with military service in the Wars of Napoleon. This particular group was led by a veteran of the War in Spain and Portugal. They trained communication, working in groups, ambushing and used their numbers to cover as much ground as possible to confuse the battalions of the army. Once these drills were done, they would eat, drink and bare-knuckle fight, But they were prepared to take on, man by man, the armed guards. They would fight them in taverns, they would hunt them into alleys. They were determined to protect their jobs, their families and their towns and counties."

The concern - Theodore Smythwaite was a serving member of the British Army. The weapons they used were army issued, by him. He said he "got them by sneaking through the window of the arsenal, and passing them to the militiamen". Teddy was part of a growing movement, expanding like wildfire after October 1831, of agitators within the Army. One soldier was shot for mutinous activity in April 1831, a first in around a year as relative calm in the military had continued throughout the post-Napoleonic era. But problems began to emerge, and by May 1832, it had reached seven per day. Low pay and the long service, which was compounded by the definition of the military's paymaster that putting down rebellions, the only job for the mostly working-class recruits still enlisted, counted as 'stoppage', meaning half-pay, to save costs. The national debt was nearly 200% of GDP in 1832 and with costs of internal policing, a small percentage of the military's use in the previous 5 years now accosting for a military occupation of the north, troops came back to promises of pay, poor conditions and overcrowding and discontent turned to outright covert agitation in Northern barracks. They would use leave to train militias in military tactics and most began adopting a tactic described as the rather derisory "catch-and-police" system, which combined policing powers at events like meetings (after all, they were here to protect their

wives, children and parents from the mob), and to "catch" Army guards on alert, arrest them and force them to convert to the other side (hopefully) or kill them (hopefully not).

In Political terms, this brought impatiences from both sides. The union leadership was split between more appetite for moderate reform in the South, but more alienation and agitation in the North and Scotland. Leaders of five of the major Unions (Scotland, Northumbria, Yorkshire, Palatine and Mercia) called on 25th April for a list of reforms in a letter to the Times, the Government paper of record. They called for elections to be held immediately, Parliamentary sovereignty, more local civic governance and end to martial law or else the leaders would advocate the National Holiday and workers would down tools on 1st May, where public meetings would elect a National Convention to decide a popular constitution. It was astounding in political terms, with Thomas Attwood signing on behalf of the Birmingham Union, showing the public opinion away from the Regent. It was interesting that subsections from

every class spoke in favour of reform; Charles Grey, an aristocrat and reformer, albeit an extremely moderate one, Henry Hunt, landed gentry and popular reformer, Joseph Parkes, the commercial class reformer of the Birmingham Political Union and schemer of agitation, thousands of the middle-class, and millions of the working class cursed now Regent nightly and secretly, in halls and backrooms in taverns, men moved against the crown.

In Ireland, the rioters began more organised, looted police armouries, and to O'Connell's disdain but growing acceptance, continued to resist violently against the Church of Ireland's tithes, but now had a growing list of reforms including Repeal and the re-establishment of an Irish Parliament with an Irish Executive. Thirty arrests made during the first wave of Tithe protests after Carrickshock were brought to trial the week of the Union Letter, on the 27th April, however, O'Connell's defence of the men, who discredited the trial by questioning juries and witnesses' ability to conduct a fair trial, saw the men acquitted and bolstered the Nationalist mood. A slight easing of the restrictions (due to a quell in violence due to National Holiday planning and the post-Tithe trial calm in tensions) and a short period of good weather (1832 was a wet year), brought people out over the 28th and 29th, especially in the South, but in Cork, the home county of Feargus O'Connor, a significant rising would occur. Men walking out of an Anglo-Irish Owned workshop in Cork City in a wildcat strike for Reform and better pay were met with an Army regiment to restore order and return the men to work. Upon arrival, the men were ambushed, carefully and precisely, and their weapons were seized. The owner was lynched and his country house was burned and the men included the Catholic RIC chief and several local rebels, who seized key buildings and declared their support for the Irish Convention. They were brutally crushed and while they had got the dates out, two days later, workshops, factories and farms downed tools in support of Repealing the Act of Union an in the sympathy with Cork and favour of reform.

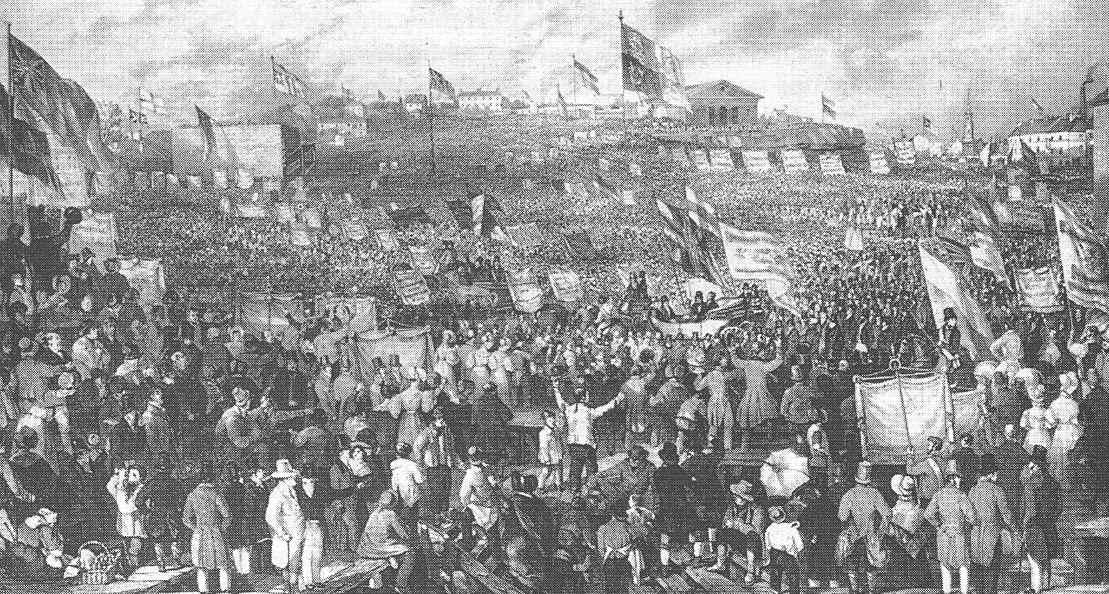

In Britain, the strikes began on May 1st, informally, but after all, attempts to contact the Regency and the Privy Council had failed, Political Unions across the north called for a Grand National Holiday to show their support for Reforms and to elect delegates to a National Convention. The Glasgow Political Union (a flagship for Scottish Radicalism), Mercian Political Union, Palatine Political Union, Bristol Political Union, Yorkshire Political Union, Northumbrian Political Union & Metropolitan Political Union all co-signed the letter calling for a four-day walkout, with the fourth day finishing with a National Convention on May 6th. In Northern Cities, middle-class business owners shut up shop, refused to pay taxes and rates, and amassed and began to protest for civic representation, the recall of Parliament, and the adoption of a new constitution that included expanded representation. Workers paraded onto the streets, cheered from their balconies by their bosses. Then, as sure as day, the Army arrived. But in Manchester, in Blackburn, in Preston, in Stockport, in Oldham, in Huddersfield, in Leeds, in Hull and Wakefield, it was all the same. The men who had ridiculously marched in the fields were ready. Again and again, armed militias of workers began to fire back, seriously arm and defeat Army regiments. In Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cheshire, Army regiments were pushed out of the city and County Divisions, who joined the fighting after the Army had attacked, were arrested and held in skirmishes in Leeds, Huddersfield & Manchester. While the Political Unions were not responsible, they maintained a level of contact with the militias in the newly radicalised Union leadership and their support was made known. Political Union leaderships were keen to make the militias aware they were on their side - a marked change from the scenes in Bristol the year before.

In essence, the "Conventions" were no more than public meetings, in which ceremonial "delegates" were elected. The real work, however, was done in the weeks leading up to the conventions amongst the Liberal Middle-Class, who began to form "Constitutional Committees" in the lead-up to the meetings to discuss the minutiae of the constitutional form. A number of them, who were connected an impressive internal postal system developed during the multitude of crises of the previous six-months, began to be influenced dramatically by the publication of the

Constitutional Code by Bentham, earlier than announced, on April 28th. This indicated a Government that protected democracy and guarded against oligarchy with a Ministry of fourteen men, elected by a Supreme Legislature and holding the confidence of it. Influencing the work of

drafters, like Richard Potter, member of the Little Circle of Philosophical who became an influential figure in these deliberations. A week before the Holiday, before the militias had intervened in Stockport, Potter contacted a member of the Committee of the Northumbrian Political Union, Frederick George Howard, and Huddersfield Radical Lewis Fenton, and proposed the adoption of Civic Charters to elect a Legislature and a Ministry for their "counties and Provinces". The Conventions, he argued,

could be used to establish permanent Government.

Jeremy Bentham, posthumous inspiration for the Philosophical Movement and leading Political Economist and Philosopher, author of the Constitutional Code

Potter's note found it's way Daniel O'Connell, who read it with interest on May 2nd. "My mind is opened with the Code, and the notion of a proliferation of Civic Charters to proclaim democracy in Britain may well be the way for us to not be left in the cold," he said in a letter to Potter on May 3rd. The meshing of liberal political ideals with the Repealer desire for Autonomy and events in the mainland convinced O'Connell that now might be the time to make the symbolic gesture to establish the Irish Parliament, under Bentham's direction. The detail was dizzying, and in O'Connell's eyes unnecessary, but O'Connell's decision swung the favour immediately to the unilateralists within the Repeal Association, Potter's argument won to localist sentiment in meetings of the Yorkshire P.U and the Palatine Union, the same night O'Connell wrote his correspondence, in meetings in Keighley & Oldham respectively. The growing movement for the declaration of Civic Charters in striking areas was complete by May 5th, when copies of the letter were sent to London and Glasgow along with the motions for the adoption of Civic Charters for the City and the country of Scotland respectively. These Charters were varied - high on detail, like Potter's draft of the Charter of Government for the County Palatines of Lancaster & Chester, and Fenton's draft of the Provincial Charter of Yorkshire, which specified an elected-Governor with the power to sign Bills into Law, a Ministry, led by a Premier, and a unicameral legislature and an independent judiciary while some, such as the City Charter for London pronounced universal suffrage and annual elections, as well as an elected Mayor, but very little else. Finally, Thomas Attwood abstained on a Union Council vote in Mercia to adopt a Provincial Charter on similar lines early on May 6th, but the vote passed and the measure to adopt a Charter was adopted, establishing an Assembly for Mercia.

"In the absence of trust, true and fair governance is this County" the Yorkshire Charter began, "it is left to the subjects themselves to declare their citizenship to the County within this Kingdom". On the day of the Convention, 100,000 people in Leeds signed the pledge, guarded by militias who swore an oath to the Charter and the County. They christened themselves, in front of the Political Union leadership, the Civic Guard of the Four Ridings of Yorkshire. In Manchester, where 115,000 gathered in St Peter's Field, site of Peterloo, their military regalia was complete with uniforms made in factories in Blackburn and Darwen, and the meeting even went so far as to elect Potter interim-Premier until an election could be held. "The Regent needs to understand this", Potter said to the Crowds in Manchester "we cannot be treated like a colony of England, filled with vagabonds and paupers. We need representation". They brought banners saying "Our Government, Our Charter" and "Representation or Death", "Blood or Bread" and "Down with Old Corruption". As Yeomen tried to break up the meeting, the Militias attacked them with Sabres before they could enter the field. This stretch of Manchester was under rebel control. After four hours, the Militias drove them out to the City limits, before meeting Militias from Stockport, Oldham, Rochdale and Huddersfield, who were rallied after reports of a Peterloo style massacre and marched across in formation to Manchester.

Agitators within local barracks saw the convention as their time to encourage mutiny. Soldiers feared retribution and reprisal if they took part in any massacre of workers in the cities, and were aware militias were approaching. Agitators, like Smythwaite, called on officers to be arrested, yearly elections called, higher pay and better conditions. In Manchester, Soldiers began to join the protesters, who brought weapons and fortified a barricade around the city on the night on May 7th, turning the National Holiday Strike action into a general mutiny of Northern Soldiers. Hasty, local recruitment to soak up unemployed, originally conceived by Wellington to better control troublesome provinces with locally recruited units. These units, littered across Northumbria, Lancashire, Cheshire, Durham, Yorkshire and the County of Lincoln began staging mass desertions, looting and a lack of discipline after the resignation of the Duke of Wellington, when he vacated his post of Commander-in-Chief as well as First Lord of the Treasury, meant officers, who themselves were wary of internal military manoeuvres and offered little in stopping the mass walkout of units between May 9th and May 15th, as military options began to become exhausted. Joyous declarations of Town, City and Provincial Governments began to be proclaimed and people celebrated on the streets. The drastic loss of control in the North discredited Earl Eldon, and moves were pondered to approach the Political Unions to bring about an end to the strike and to bring workers and soldiers back to work.

The Regent was forced into a decision, and she made one, dismissing Eldon and, against the advice of Conroy, issuing writs for elections on May 15th, with Parliament set to convene in September and elections to take place between 1st June and 15th August. Political Union councils voted unanimously that an interim Ministry led by Grey would be a condition of ending the strike, along with amnesty for rioting cities and counties, recalling Parliament and recognition of the charters. Metropolitan Political Union leader, 32-year-old William Lovett, also demanded the Regent use her Royal Assent to pass legislation to conduct the election under universal suffrage. "The Union is under threat," she said in a letter to Wellington, "I believe we need to act." She elected to begin negotiations with Grey, whom she had sidelined not 8 and a half months before. Grey desired to form a Government but wanted to curb the powers of the Lords to block the Reform Act and perhaps give it Royal Assent without Lord's approval. Essentially, the choice was between an uprising in the North which could, and probably would spread to Ireland and Scotland, major cities like Bristol, Newcastle, Nottingham and Birmingham and then probably London, or institute a major constitutional overhaul as a Regent, not the Queen.

After deliberation, which was fraught and resulted in a crowd of 20,000 appeared to find out the outcome, the Regent decided she would decide in the morning, and dismissed Grey without asking him to form a Government. On his exit from Bushy House (the Regent's temporary residence since the assassination of William), a man in County Division uniform charged his carriage and planted a bomb which exploded, killing Grey, the armed man and fourteen people. The crowd turned vicious, rushing the Guards, who were overwhelmed by the bomb and immediately the crowd, assuming the Regent had tried to assassinate Grey, attempted to find and arrest the regent. They stormed the palace and found the Regent in a study, where workers and commoners with pikes and sabres pulled her out, elected a "popular magistrate" by a show of hands and sentenced her to death. As workers fought yeomen rushing to save the Regent, and Police trying to storm the House, on the balcony, a man pierced her with a sabre to a cheering crowd and was forced to hack her several times before Army units were able to arrive and back up the Guards, most of whom had been overwhelmed by the furious crowd. The Queen, however, simply couldn't be accounted for. Britain suddenly had no Regent, no Monarch, no Prime Minister and no Parliament. The Police overwhelmed most of the leaders, but the damage was done. Britain had descended completely into the unknown.

END OF PART 1