New update. I'd like to point people back to

Jon's excellent post on the region before contact for extra context!

The Cursarines

The islands east of Rijkhaven and north of Nova Ispania had acquired a certain reputation for being a refuge for corsairs raiding the burgeoning shipping passing the Antillean sea. A few Fula warlords, or rather pirate lords, most notably the king of Guada [Martinique], had established themselves in the region, and a Canary Norse haven had for quite some time existed on the western side of Rothulland [Guadeloupe]. A Taino chiefdom existed on Piragua [Dominica] and the eastern half of Rothulland was occupied by the chiefdom of Cahaya, both of which of whom were happy to raid passing ships, and both of which gained population when Aquitaine and the Twin Crowns asserted their authority over the northern and southern Cursarines and pushed out or enslaved their remaining Taino inhabitants. The Islas Sucradas [St Vincent and the Grenadines] and especially, Sant-Joan [St Lucia] would become major Aquitanean sugar producers as well as stopover points for ships coming to and from Nova Aquitainia. The Twin Crowns claimed all lands north and west of the island of Santafides [Antigua], though in practice the islands would be sparsely settled at first and home to a number of Breton and Neustrien ventures. The New Vriesland colony [South Carolina] would be established in 1320 essentially as a giant rice plantation so that the islands of what would later be dubbed "New Zeeland" could devote themselves to cash crops even more seriously...

The island of Barbuta [Barbados], however, may have been the most infamous pirate port of all, despite being nominally claimed by Nova Ispania. The small Ispanian fortress of San Martin and the Mauri outpost of Novupoltu were quickly eclipsed by the Masamida treaty port of Salli, which became home to corsairs, prostitutes, and freebooters of all nations. It was here that Sergio Agus, a captain of Mauri/Ispanian descent, made an early mark. Leading a coterie of Mauri, Ispanian, and Masamida sailors, and a smaller group of Fula and Italian muscle, his red flag would terrorize Bharukacchi ships and ports until in 1280 the Bharukacchi seized a the bright idea: to pay Agus to target Red Swan-affiliated settlements instead - like those of Nova Ispania itself. Accordingly, Agus would mount successful raids on San Paolo and Porto San Francisco [Cumana], only to be repulsed at Novo Olispo. He and his crew took their three remaining ships and sought to repair and recuperate at Sant-Prosper, which still maintained itself as a neutral port. It was here that he would have an encounter with destiny...

The Conquest of Toumpes

One of Nova Aquitainia's most prominent subjects was Phillippe Godolin. The first Aquitanean to discover the Procellaric ocean, and Western discoverer of Lake Nicoya [Nicaragua], he had also explored much of the Pacific coast north of the equator and was familiar with sight of groups of Solvians visiting the coast in large balsa wood rafts. Logically, he had deduced, they must come from someplace. He was approached by Henri Garat, the second son of the Comte of Bearnia [Bearn], accompanied by his brothers Marcos and Frederic. The Garat brothers had heard from returning scouts of rumors of a land of "large villages" to the south. Finally, they thought, they could conquer a realm like that of the Moisca, and attain a worthy title and riches to match Duke Thomas of Moisca, who Henri still somewhat resented for not rewarding him after his arduous portion of the campaign. Godolin and the Garats both had brothers back in Aquitaine petitioning at court to advance the family interest. The fourth Garat brother, Augustin, received a boon from the Aquitanean king for a discreet favor and returned to their ancestral estate near the Vasconian border to raise additional troops. He would travel to the New World with Phillippe Godolin's brother, Charles, and a group of a dozen cavalrymen and 36 footmen in heavy plate. Along with Godolin and the Garat brothers' existing followers, which had expanded as Aquitanean venturers were drawn overseas, this created a force of 157 Aquitanean men-at-arms. This was impressive, but Garat knew well that he would prefer a larger number still to mount a Votive campaign, especially given their possession of no cannons and rather small number of cavalrymen.

The expedition set out nonetheless in 1281 with supplies provided by Exarch Raoul de Lemoges, with a promise to donate a half-share of any seized wealth to the Exarch's treasury. They would board ships constructed by Godolin's men and sail south, toward glory and infamy. They would first encounter a balsa raft outside of a city, which the native translators claimed was called "Toumpes". The raftsmen were perhaps not as surprised to see a strange vessel like this as might be expected, as, after all, Toumpes had been visited by the circumnavigating Fleet of Fu Youde decades before. Then, Toumpes had been a recently-abandoned shadow of itself, devastated by plague. In the intervening years the city had been re-occupied and was beginning to approach something akin to its old population again. The Westerners would march into town, flanked by citizens richly clothed in wool and cotton cloth, and summarily turned a meeting of parley into a play for hostages, taking the leader of the city and the heads of several elder families hostage and asserting control over the city with little bloodshed. As leader of the largest band Henri Garat was proclaimed the "Duke of Toumpes" while the Westerners regrouped, ready to venture further south after consolidating their position. Frederic Garat was sent north with proof of their spoils to recruit additional men for the next leg of their expedition.

In stepped Sergio Agus. His ships were badly damaged and he would need to spend quite some time repairing them in Sant-Prosper. However, he was approached by Frederic Garat and offered the opportunity to reap the benefits of a new Votive expedition. Salivating at the chance for a share of spoils like those of the Moisca, Agus accepted, providing two small, portable cannons captured from Ispanian fortifications, and bringing in his polyglot collection of toughs and rapscallions. Along with a few more Aquitainean latecomers, this brought the total manpower of their expedition up to 232. Henri Garat and the Godolins had some reservations about the rough nature of these recruits but accepted that they would suffice for their Votive purpose. Ahead of them, the natives of Toumpes told them, lay the golden lands of the Chimor and the Chincha...

The Kingdom of Chimor

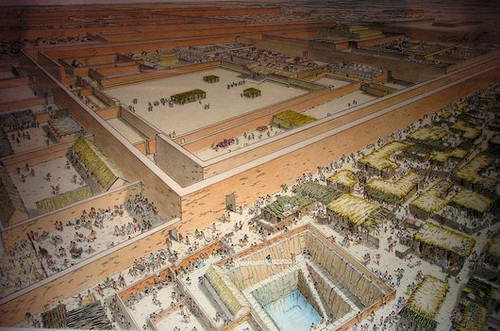

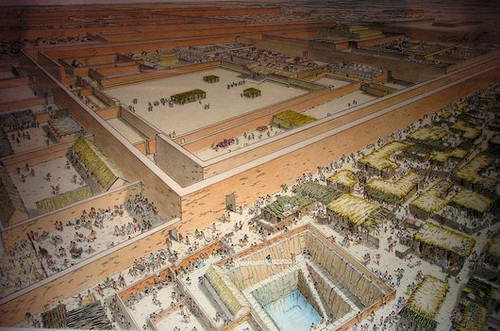

The thirteenth century had been a time of turmoil and upheaval in the Andes. The Wari and Tiwanaku polities had collapsed, and regional cultures were increasingly asserting their own influence. Foremost among their successors was the empire of the Chimor. Their capital, Chan Chan, was situated on the desert coast of the Moche Valley was surrounded by hundreds of square km of irrigation works. The capital itself was dominated by the Citadelos, enormous palaces owned by the nobility, who were a caste apart in Chimor society. The Chimor monarchy was traditionally succeeded by his most capable relative; the other direct descendants of each monarch venerated their progenitor's mummified body and inhabited a large palace compound in Chan Chan surrounded by adobe walls and full of large storehouses, the sprawling Citadelas. From within, each royal clade managed the lands conquered by their ancestor and other tribute. The Chimor monarchy compelled the best artisans of all subject nations to reside outside the walls of the Citadelas in Chan-Chan, often subject to the clade that had conquered their lands. The Chimor also had a number of dependent cities subject to varying degrees of tribute and controlled the nearby Chicama and Viru valleys. Their craftsmanship and control of the trade of

Spondylus shells, a precious resource in Andean cultures, gave them a dominant position in regional trade, matched only by the Chincha.

Chan-Chan. The largest city in the Andes, with a population of 40,000 and covering 18 sq km.

The kingdom of Chimor, due to its size, had its power proportionately less affected than its smaller neighbors by the the plagues of the 1250s and in 1271 the king Yasencor invaded the neighboring northern Jetecapete Valley, bringing its Sican inhabitants under direct control. The Sican were cousins to the Chimor with a similar pantheon and desert lifestyle, and were governed from the regional capital of Farfan, built on top of a razed Sican settlement. The monarch Yasencor had died in 1277, and his clade controlled much of the tribute from the newly conquered lands. His nephew, the new king Choumuncor, had need of tribute of his own, and mounted a campaign to bring the lands south down to the Casma valley into deeper tribute relations. He had just begun construction on a new regional outpost at Manchan in 1282 when 180 men from the Votivist expedition departed Toumpes heading south to the rumored land of gold...

The Gates of Chan-Chan

When the Votive flotilla reached sight of Chan Chan, the Westerners were stunned. "It is the Solvian Babylon," wrote Fr. Joan de Vilay, a priest travelling with the expedition, "a city of mud brick citadels and artisans of a thousand tongues, of pack drivers leading laden

Calcal [1] from distant provinces, of riotous tapestries, of golden opulence and the blood of sacrifice. Some men wondered aloud if they had died unknowing and passed into Paradise, so strange and wondrous were the things we saw in those days." The Votivists had hoped for a rich target but had not expected to find a city that could rival any capital in Europe in size and especially, splendor. Henri and Augustin Garat, Phillipe Godolin, and Sergio Agus went ashore with a few dozen followers while the ships remained at anchor in sight of the city. A crowd had gathered to watch them come ashore and they were quickly greeted by a richly dressed envoy of King Choumuncor and ushered into his palace, still under construction, to meet with the King.

[1] Chimor for llama

The walls of the Citadela d' Choumuncor

The king was treated with total reverence by his subjects; they were not allowed to address or look at him directly, and a servant was employed to lay crushed

Spondylus dust before his feet so that his path might always be blessed, when he was not being carried by manservants on his palanquin. Henri Garat, Phillippe Godolin, Fr. de Vilay, Sergio Agus, and a few select retainers were received in a wide hall draped in colorful patterned tapestries and intricately carved and painted walls.

The exact words that were said have been lost to history, but general accounts of the conversation they had remain consistent. Choumuncor congratulated the Westerners on their conquest of Toumpes and offered the Votivists "twenty calcal loads of fine goods and textiles" as a "token of his abundance and generosity". The king then asked the Westerners if they came to Chan Chan in peace or in war.

For previous Votivists this had always been an unambiguous answer. However, the sheer size of the city and the power it represented had terrified the Westerners. A kingdom like this might be capable of raising an army of thousands... The Europeans knew from experience that their arms and armor gave them an utterly dominant edge over the natives, but at the same time, the Votivists had only ever fought native bands numbering in the hundreds at most. They decided to adopt a more diplomatic approach.

Henri Garat introduced himself as the emissary of the Empire of the Franks, and Fr. de Vilay, of the Pope. He explained that he had been sent to expand the trade of his master the King of Aquitaine, and to spread the faith. He explained that they had come from across the sea and were quite grateful for the hospitality; and that they had only the best intentions for the Chimor king and his people.

To Choumuncor this made a certain amount of sense. The limited habitat of the spiny oyster, or

Spondylus, was in the waters off Toumpes and points north; thus whoever controlled Toumpes, controlled what the Andeans considered a very valuable resource. The Aquitaineans must, he thought, desire to leverage their new near-monopoly on the shells. Choumuncor offered to host the delegation and open trade with their ships, much as had been done for Fu Youde in years past, hoping to wine and dine them into offering an equitable deal.

Spondylus

A few weeks passed. More and more Europeans began to come ashore and the exchange of information between Andeans and Europeans progressed. Learning that the king had been considering a campaign against the remaining Sican cities in the Lambayeca Valley, Henri Garat proposed a deal to the King: the Europeans would lead a campaign to conquer the valley, and in turn receive a half-share of the valley's tribute. They would also agree to pay a regular tribute of Spondylus to the King "in exchange for his protection". This amounted to a proposal to become the King's mercenaries and subjects. Choumuncor was somewhat suspicious of the motives of the Votivists in offering this, but was in the end tempted by the bargain deal he had been offered in terms of tribute; the shells were, after all, worthless to the Europeans and so they could afford to be generous.

In early 1283 a group of 100 Europeans, including Phillippe Godolin, Marcos Garat, and Sergio Agus, marched at the head of a 1,500 strong Chimor army towards Tucumay, the capital of the Sican polity.

Tucumay was a city of earthen platforms and mudbrick pyramids atop which the nobility dwelled. The largest of these platforms was nearly 1 km long.

The battle that ensued was a one-sided slaughter. The Sican army was comparable in size to the Chimor's, but the Europeans were close to invincible as far as native weaponry was concerned. The men armored in heavy plate could deflect any blow from the bronze weapons or stone projectiles used by the natives; and the natives had no idea whatsoever what it meant to experience a cavalry charge. Men in lighter mail or plate could still survive blows that would have killed native soldiers. The Europeans had virtually no losses while Sican warriors died in the hundreds. The sack of Tucume was similarly merciless.

Pacatnamo

The general of the Chimor, Pacatnamo, was impressed by the Europeans' arms. He was an extremely capable general, one that many had thought would succeed Yasencor, and he had come to the sudden realization that they far outmatched not only the Sican army, but likely the Chimor's as well, and knew they must be kept appeased. Pacatnamo called Garat, Godolin, and Agus to meet in his camp, and had what turned out to be a very productive discussion. The Europeans would back him in a bid to take the Chimor throne; in return, he would appoint Phillippe Godolin lord of all Tucumay (rather than half) and Pacatnamo would agree to learn the ways of their strange god.

Messages were sent to the Europeans remaining in Chan Chan about the plot, and informed to wait until the army appeared at the gates of the city to attempt to take Choumuncor hostage from the inside. In late 1283 the Chimor army began a return march south, leaving behind Phillippe Godolin, the new "Duke of Tucumay", and some retainers to secure the valley. Choumuncor got wind of the plot, however, while the army was still in transit; furious, he attempted to have the Votivists killed. A group of 20 Aquitaineans managed to flee through the northern gates and rendezvous with the main group. 12 men were cornered into a storehouse in Choumuncor's half-finished Citadela; they were subsequently killed when it was set on fire to root them out. The remainder escaped to the ships, still anchored out at sea.

King Choumuncor marched out with an army 1,000 men strong and forced an engagement at a narrow pass, which he hoped would nullify the advantage of the European's horses. However, he had not counted on the two cannons, which were granted a wide field of fire from the high ground. The cannons terrified the king's army and the Europeans still had a dominant edge on foot. The battle was lost and Choumuncor himself was slain, some say by a cannonball, others say by Pacatnamo's elite warriors.

The new King Pacatnamo installed himself in Choumuncor's old palace but it soon became obvious that the Europeans were pulling the strings. Garat began construction on a port outside of Chan Chan he named Morlans after his family's ancestral seat in Aquitaine. Europeans were assigned the choicest honors and offices, enraging the other members of Pacatnamo's clade, who had hoped to benefit from his rise. The Europeans became increasingly rapacious for tribute, especially in the form of gold. The question of faith remained dicey: Pacatnamo allowed himself to be baptized but refused to condemn the traditional priests and, especially, the ancestor cults of the nobles. It was all rendered moot, however, when the shaking sickness passed through Chimor for the first time in 1285.

The Deluge

The mosquito-borne plague had already burned a path through Nova Ispania and Nova Aquitania, devastating both native and foreign men alike, though the Fula and other Africans tended to fare better than most. It had a devastating effect on the Chimor, killing thousands in Chan-Chan and striking down, among others, King Pacatnamo, and also killed a swathe of Europeans.

The Votivists now had no pet monarch. Pacatnamo's clade raised one of their number, a lord Hoscanamo, as new King, and attempted to destroy the Votivists as swiftly as possible. Many were scattered across the Chimor kingdom and were picked off one by one. A large fraction had already departed south, commanded by Sergio Agus, who intended to secure a duchy of his own by conquering the valley of the Itsma. A force of 40 men were waylaid returning from a mission to bring the cities around Manchan to submission. Trapped in a fortress in the desert with its only water source cut off by the Chimor, they would lose a substantial number to thirst before staging a desperate breakout that would see only 13 survivors limp to safety in Tucumay; Frederic Garat was among their losses. Another 40, including Marcos Garat were driven out of Chan Chan and into the highlands, to Hoscanamo's later regret.

Sergio and his forces had easily subdued the Itsma and established a camp at the oracle of Pachacamoc. Returning by sea to Morlans, he was surprised to find it had been set aflame. He gathered a few survivors and set sail for Tucumay, to confer with Henri Garat and Phillippe Godolin over how to respond. There, the three commanders compared notes. 77 of the original 232 were present in Tucumay; 48 had been left in Toumpes; and another 29 remained in Itsma. The rest were dead or otherwise unaccounted for. It was decided that Sergio and Henri would sail north and return to Sant-Prosper, to petition the Exarch for additional reinforcements....

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/spondylus_princeps-5922d8573df78cf5fab99027.jpg)