5 of them and at the 6th one, after winning by 7x1, they annex BrazilWill this Mexico ever win a world cup? 😢

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Mexican Century: An Alternate Mexican History

- Thread starter AlexGarcia

- Start date

God I wish, but I don't know if there will be a FIFA in the first place. Football for sure, why not.Will this Mexico ever win a world cup? 😢

The Republican-Monarchist Question, Part 1

During most of 1811 and part of 1812 the political situation in the territories controlled by the revolutionary Junta changed from a general consensus to a division into two major political blocs: Republicans and Monarchists. In part, this division was produced by the lack of a generalized royalist opposition, as the main pockets of royalist resistance (Acapulco and Veracruz) were under insurgent siege, with the rest of the territories of the so-called "Mexican America" accepting peacefully or violently the new revolutionary government (excluding, of course, Cuba, the Philippines and Central America). The proclamation of the Republic of Venezuela in the midst of the collapse of the Viceroyalty of New Granada only provoked the acceleration of an inevitable division among the nascent Mexican politicians.

Originally, the insurgent movement revolved around the formation of a provisional government to act as sovereign and representative of the monarch Ferdinand VII. However, Hidalgo himself already admitted that accomplishing this objective was, although not impossible, quite difficult. The mere idea of popular sovereignty instead of the divine right of kings as a political basis had slowly fostered the possibility of full independence for the Mexican nation. Hidalgo was in favor of a Mexican monarchy independent of the Spanish government, but with the same king (a Personal Union). In addition, the constant struggle and the military and political experience acquired by different characters of the Independence led them to assume that reconciliation with Spain would not be possible. After all, there was no guarantee that the Spanish government, once the war against Napoleon was over, would agree to recognize the measures of the Junta, under the (partly true) justification that it was an insurrectionist government, which for a change had imprisoned the acting Viceroy.

After the ratification of the Treaty with the United States that recognized the Junta as a legitimate government, and with a good part of the country under de facto control of the insurgents, Ignacio López Rayón called for the reform of the Junta de Gobierno into a "true" political body that could have coherence, legitimacy and, above all, could manage the revolutionary efforts of the Insurgent Army in a disciplined and efficient manner. Although Hidalgo was reluctant to further abandon the possibility of reconciliation with Spain by reforming what was supposed to be a temporary political body, he did not oppose the dispositions given by Rayón, and the rest of the insurgent leaders supported his call to a greater or lesser extent. The Junta of Government was renamed as "Suprema Junta Nacional de la América Mexicana" (Supreme National Board of the Mexican America) or simply "Suprema Junta Mexicana" (Supreme Mexican Board). As part of the provisions to be applied within the reforms to the new political body, certain individuals were to be elected to act as leaders in charge of certain areas of the country as general captains. All captains would be headed by a Chairman who would, de facto, act as the leader of the country. The main objective of said Chairman, together with the general captains, who would act as his representative and advisors, would be to properly organize the military and civilian finances, apply justice to the territories governed by the Supreme Junta, form a stable currency, intimidate the insurgent caudillos who committed abuses to the civilian population or committed acts of corruption; and, above all, delimit the form of government that the Mexican Nation would have in a definitive manner.

The general captains who were elected were: Morelos, Rayón, Allende, Mariano Jimenez, and Aldama. With the exception of Morelos, all had been elected for having been part of the original insurrection in Queretaro, while Morelos had been elected on the recommendation of Hidalgo himself, who saw a certain affinity in him (besides, Morelos had originally been his student years before). The Chairman of the Junta, for obvious reasons, would be Hidalgo, the Generalissimo of the Americas. Quickly, the captains divided their zones of operations from which they could coordinate among themselves, and control matters related to the payment of taxes, the abolition of slavery, intelligence operations against possible royalist sympathizers, and the reactivation of the Novo-Hispanic economy. Hidalgo, for his part, was to appease the interests of each of his captains (the promotion of unity), form new laws or modify existing ones, and approve military acts in aid of his captains. In short, the Supreme Junta would act as a primordial form of Executive power in the country, in the absence of a parliament (Legislative power) and a Tribunal (Judicial power). However, Rayón declared the intention to expand the Supreme Junta with multiple representatives from the different provinces and intendencies of New Spain, in order to form a future legislative body that would encompass the entire Nation.

It was during the formation of the Supreme Junta that Morelos and Rayón began to clash over the question of the form of government: Rayón explicitly supported the formation of a constitutional monarchy linked to Spain by a personal union, as did Hidalgo. On the other hand, although not explicitly in favor of the republic, Morelos did not see subordination to the Spanish royal institution as a possibility, since the situation in Spain itself was complicated, and there was no guarantee that Ferdinand VII would become monarch again; therefore, his proposal was for a "neutral" government that would declare itself neither monarchic nor republican, at least until peacetime could arrive. Hidalgo, as Chairman of the Junta, ordered the captains to draw up draft documents to be discussed among the six members of the Junta, as well as with other important individuals within the insurgent movement. These documents were to serve for the formation of a provisional constitutional document that would define the form of government of the future state under a consensus in which the majority agreed.

It was during the first months of 1812 that both captains were drafting their own proposals for a possible provisional Constitution.

Originally, the insurgent movement revolved around the formation of a provisional government to act as sovereign and representative of the monarch Ferdinand VII. However, Hidalgo himself already admitted that accomplishing this objective was, although not impossible, quite difficult. The mere idea of popular sovereignty instead of the divine right of kings as a political basis had slowly fostered the possibility of full independence for the Mexican nation. Hidalgo was in favor of a Mexican monarchy independent of the Spanish government, but with the same king (a Personal Union). In addition, the constant struggle and the military and political experience acquired by different characters of the Independence led them to assume that reconciliation with Spain would not be possible. After all, there was no guarantee that the Spanish government, once the war against Napoleon was over, would agree to recognize the measures of the Junta, under the (partly true) justification that it was an insurrectionist government, which for a change had imprisoned the acting Viceroy.

After the ratification of the Treaty with the United States that recognized the Junta as a legitimate government, and with a good part of the country under de facto control of the insurgents, Ignacio López Rayón called for the reform of the Junta de Gobierno into a "true" political body that could have coherence, legitimacy and, above all, could manage the revolutionary efforts of the Insurgent Army in a disciplined and efficient manner. Although Hidalgo was reluctant to further abandon the possibility of reconciliation with Spain by reforming what was supposed to be a temporary political body, he did not oppose the dispositions given by Rayón, and the rest of the insurgent leaders supported his call to a greater or lesser extent. The Junta of Government was renamed as "Suprema Junta Nacional de la América Mexicana" (Supreme National Board of the Mexican America) or simply "Suprema Junta Mexicana" (Supreme Mexican Board). As part of the provisions to be applied within the reforms to the new political body, certain individuals were to be elected to act as leaders in charge of certain areas of the country as general captains. All captains would be headed by a Chairman who would, de facto, act as the leader of the country. The main objective of said Chairman, together with the general captains, who would act as his representative and advisors, would be to properly organize the military and civilian finances, apply justice to the territories governed by the Supreme Junta, form a stable currency, intimidate the insurgent caudillos who committed abuses to the civilian population or committed acts of corruption; and, above all, delimit the form of government that the Mexican Nation would have in a definitive manner.

The general captains who were elected were: Morelos, Rayón, Allende, Mariano Jimenez, and Aldama. With the exception of Morelos, all had been elected for having been part of the original insurrection in Queretaro, while Morelos had been elected on the recommendation of Hidalgo himself, who saw a certain affinity in him (besides, Morelos had originally been his student years before). The Chairman of the Junta, for obvious reasons, would be Hidalgo, the Generalissimo of the Americas. Quickly, the captains divided their zones of operations from which they could coordinate among themselves, and control matters related to the payment of taxes, the abolition of slavery, intelligence operations against possible royalist sympathizers, and the reactivation of the Novo-Hispanic economy. Hidalgo, for his part, was to appease the interests of each of his captains (the promotion of unity), form new laws or modify existing ones, and approve military acts in aid of his captains. In short, the Supreme Junta would act as a primordial form of Executive power in the country, in the absence of a parliament (Legislative power) and a Tribunal (Judicial power). However, Rayón declared the intention to expand the Supreme Junta with multiple representatives from the different provinces and intendencies of New Spain, in order to form a future legislative body that would encompass the entire Nation.

It was during the formation of the Supreme Junta that Morelos and Rayón began to clash over the question of the form of government: Rayón explicitly supported the formation of a constitutional monarchy linked to Spain by a personal union, as did Hidalgo. On the other hand, although not explicitly in favor of the republic, Morelos did not see subordination to the Spanish royal institution as a possibility, since the situation in Spain itself was complicated, and there was no guarantee that Ferdinand VII would become monarch again; therefore, his proposal was for a "neutral" government that would declare itself neither monarchic nor republican, at least until peacetime could arrive. Hidalgo, as Chairman of the Junta, ordered the captains to draw up draft documents to be discussed among the six members of the Junta, as well as with other important individuals within the insurgent movement. These documents were to serve for the formation of a provisional constitutional document that would define the form of government of the future state under a consensus in which the majority agreed.

It was during the first months of 1812 that both captains were drafting their own proposals for a possible provisional Constitution.

First seal of the Supreme Junta, made in 1811.

The Republican-Monarchist Question, Part 2: The "Constitutional Elements"

On April 18, 1812, Ignacio Rayón sent Hidalgo his constitutional proposal, officially titled "Proyecto de Constitución del Imperio Mexicano" (Draft Constitution of the Mexican Empire), although it is better known today as the "Elementos Constitucionales" (Constitutional Elements). In this document, Rayón expressed his personal vision of how Mexican society should be provisionally governed at birth, with a strong emphasis on the union between democratic elements of the Enlightenment era and the maintenance of Catholic hegemony in the country, as well as the personal union with the monarch Fernando VII, still imprisoned by French troops in Spain. The document is composed of a preamble, the development (38 Articles) and a conclusion by Rayón himself. Morelos, although against Rayón's pro-monarchist character, would admit that the Constitutional Elements would be helpful for the formulation of his own document, developed and given to Hidalgo afterwards. The Constitutional Elements are considered the first draft of Mexico's National Constitution, although unlike Morelos, Rayón was not too much influenced by the Constitution of the United States, being more attached to enlightened despotism.

The preamble states [1]:

The preamble states [1]:

The independence of America [the Mexican America] is too just even if Spain had not substituted the government of the Bourbons for that of some Juntas, whose results have been to bring the Peninsula to the brink of its destruction. The whole Universe, even the enemies of our happiness, have known this truth: but they have endeavored to present it as abhorrent to the unwary, making them believe that the authors of our glorious independence have had other ends, that they are either the wretches of total wantonness or the odious of absolute despotism.

The former movements have lent appearance to their opinion. The expressions of oppressed and tyrannized peoples in the twilight of their liberty have pretended to identify themselves with those of their chiefs, often needing to condescend, ill of their degree, and our events are found announced in the public papers almost at the same time that we are frightened by the most respectable court of the Nation. Only the profound knowledge of our justice could overcome these obstacles.

The conduct of our troops, which present a vigorous contrast to that of those perfidious enemies of our liberty, has sufficed to confound the calumnies with which those gazetteers and sycophantic publicists have endeavored to denigrate us. The very court of our Nation has witnessed the brutal licentiousness and scandalous dealings of those proclaimed defenders of our religion, they seal their triumphs with impiety, the blood of our defenseless brethren, the destruction of numerous populations and the profanation of sacrosanct temples: here are the results of their triumphs. Even all this does not suffice to make these proud Europeans confess the justice of our petitions, and they lose no time in making the nation believe that it is threatened by a frightful anarchy.

We, then, have the unspeakable satisfaction and high honor of having merited that the free peoples of our country compose the Supreme Court of the Nation and represent the Majesty which alone resides in them. Although we are principally occupied in bringing down with cannon and sword the phalanxes of our enemies, we do not want to lose a moment to offer to the whole universe the elements of a Constitution that fixes our happiness; it is not a legislation that we present, this is only a work of deep meditation, of quietude and peace, but to manifest to the wise what have been the feelings and desires of our people, and Constitution that may be modified by circumstances, but in no way become others.

The Articles say [2]:

The former movements have lent appearance to their opinion. The expressions of oppressed and tyrannized peoples in the twilight of their liberty have pretended to identify themselves with those of their chiefs, often needing to condescend, ill of their degree, and our events are found announced in the public papers almost at the same time that we are frightened by the most respectable court of the Nation. Only the profound knowledge of our justice could overcome these obstacles.

The conduct of our troops, which present a vigorous contrast to that of those perfidious enemies of our liberty, has sufficed to confound the calumnies with which those gazetteers and sycophantic publicists have endeavored to denigrate us. The very court of our Nation has witnessed the brutal licentiousness and scandalous dealings of those proclaimed defenders of our religion, they seal their triumphs with impiety, the blood of our defenseless brethren, the destruction of numerous populations and the profanation of sacrosanct temples: here are the results of their triumphs. Even all this does not suffice to make these proud Europeans confess the justice of our petitions, and they lose no time in making the nation believe that it is threatened by a frightful anarchy.

We, then, have the unspeakable satisfaction and high honor of having merited that the free peoples of our country compose the Supreme Court of the Nation and represent the Majesty which alone resides in them. Although we are principally occupied in bringing down with cannon and sword the phalanxes of our enemies, we do not want to lose a moment to offer to the whole universe the elements of a Constitution that fixes our happiness; it is not a legislation that we present, this is only a work of deep meditation, of quietude and peace, but to manifest to the wise what have been the feelings and desires of our people, and Constitution that may be modified by circumstances, but in no way become others.

The Articles say [2]:

1. The Catholic Religion will be the only one, without tolerance of any other.

2. Its Ministers hitherto in office shall continue in office, endowed with their offices.

3. The dogma will be sustained by the vigilance of the Tribunal of the faith which will distance its individuals from the influence of the constituted authorities and the excesses of despotism.

4. The Mexican America is free and independent of every Nation.

5. Sovereignty emanates from the people and resides in the person of the monarch Ferdinand VII, represented through the Supreme National Board of the Mexican America, to be reformed in a Supreme Mexican Congress.

6. No other right to this sovereignty can be attended to if it is detrimental to the independence and happiness of the Nation.

7. For the representation of the provinces, five vocales [Congress Representatives] shall be granted to each province, who shall be elected by the Supreme Board and shall function provisionally as the composition of the Supreme Mexican Congress.

8. The functions of each vocal shall last five years; the oldest acting as President, and the most modern as Secretary in acts reserved, or comprising the whole Nation.

9. They shall not all be elected in one year, but successively one each year, the oldest one ceasing in his functions in the first year.

10. Before the reunification of the Empire is achieved, the elected vocales shall not be replaced by others.

11. In the case of the vocales who are so at the glorious moment of the reunification of the Empire, the time of their functions shall begin to be counted from this time.

12. The vocales shall be inviolable during their term of office, unless they hold positions of high treason and with the explicit knowledge of the other members.

13. The circumstances, incomes and other conditions of the vocales who are and have been, shall be reserved when this constitution is formalized.

14. There shall be a Council of State for cases of declaration of war and adjustment of peace, which shall be attended by the Officers of Brigadier above, the Supreme Board not being able to determine without these requirements.

15. The Supreme Board will agree determinations with the Council in case of establishing extraordinary expenses, obligating national goods, or talking about inherent increases that pertain to the common cause of the Nation, under previous debate and consideration.

16. The offices of Grace and Justice, War and the Treasury, and their respective Courts, shall be systematized with knowledge of the circumstances.

17. There shall be a National Protector appointed by the representatives, as soon as the war is over.

18. The establishment and repeal of laws, and all business which interests the Nation, shall be proposed by the National Protector before the Supreme Mexican Congress, in the presence of the representatives who lent their promotion or descent.

19. All neighbors of force who favor the liberty and Independence of the Nation, shall be received under the protection of the Laws.

20. Every foreigner that wants to enjoy the privileges of being a Mexican citizen will have to deliver letter of nature to the Supreme Board that will grant it with agreement of the respective City council and dissent of the National Protector; but only the Patricians will have employment, without privilege or letter of nature.

21. Although the three Powers, Legislative, Executive and Judicial, are proper to the sovereignty, the Legislative is so inerrant that it can never communicate it.

22. No employment, whose fee is paid out of the public funds, or which elevates the person concerned from the class in which he lived, or gives him greater luster than his equals, can be called of grace, if not of rigorous justice.

23. Every representative shall be appointed every three years by the respective City Councils, the candidates being the most honorable and proportionate persons from the capitals as well as from the towns of the District.

24. Slavery shall be entirely prohibited.

25. Those born after the Independence of the Nation, will not be hindered except by personal defects, without the class of their lineage being an obstacle; the same must be observed with those who represent the rank of Captain above, or who accredit some service to the Nation.

26. The Ports shall be free to foreign nations, with such limitations as to ensure the purity of dogma.

27. Every person who has been a perjurer to the Nation, without prejudice to the penalty to be applied to him, is declared infamous and his property will belong to the Nation.

28. The destinies of Europeans, of whatever class they may be, and equally of those who have aided the enemy's cause, are declared vacant.

29. There shall be absolute freedom of the press in scientific and political matters, provided that they observe the aims of enlightenment and do not offend the established legislations.

30. The examination of craftsmen shall be prohibited.

31. Everyone shall be respected in his own house as in a sacred asylum and shall be administered with such amplifications and restrictions as the circumstances of the celebrated law "Corpues haves de l'England" may offer.

32. Torture is hereby prohibited as barbarous without discussion.

33. The days of October 2, day of National Independence; February 17, day of the liberation of Mexico City; and December 12, consecrated to our most amiable protector Our Lady of Guadalupe, are declared to be solemnized as the most august days of our Nation.

34. Four military orders shall be established, which shall be that of Our Lady of Guadalupe, that of Hidalgo, that of the Eagle and that of General Allende, and other meritorious citizens and political servants who consider themselves worthy of this honor may also obtain them.

35. There shall be in the Nation four large Crosses respective to the aforementioned orders.

36. There shall be in the Nation five General Captains and a President-General, called Generalisimo; it being possible to add or diminish the number of Captains if necessary.

37. In cases of war, they will propose the officers of Brigadier above, and the Councilors of war to the Supreme Mexican Congress, being the Generalisimo the one in charge of the executive and combination cases, investitures that will not confer graduation nor increase of income that will close concluded the war and will be able to be removed in the same way that it was constituted.

38. The five current General Captains of the Supreme Board will remain as Captains, even when they cease their functions officially, until the Independence can be formalized.

The conclusion says [3]:

Here are the main foundations on which the great work of our happiness is to be based. It rests on liberty and independence, and our sacrifices, though great, are nothing in comparison with the flattering prospect that is offered to you for the last period of our vision, transcendental to our descendants.

The American [Mexican] people, forgotten by some, pitied by others, and despised by the greater part, will now appear with the splendor and dignity to which they have become entitled by the bizarre way in which they have broken the chains of despotism.

Cowardice and idleness alone will infame the citizen, and the temple of honor will open indistinctly the gates of merit, and virtue.

A holy emulation will lead our brethren, and we shall have the sweet satisfaction of saying to you: We have helped and directed you, we have caused abundance to be substituted for scarcity, liberty for slavery, and happiness for misery.

Bless, then, the God of destinies, who has deigned to look with compassion upon his people!

The American [Mexican] people, forgotten by some, pitied by others, and despised by the greater part, will now appear with the splendor and dignity to which they have become entitled by the bizarre way in which they have broken the chains of despotism.

Cowardice and idleness alone will infame the citizen, and the temple of honor will open indistinctly the gates of merit, and virtue.

A holy emulation will lead our brethren, and we shall have the sweet satisfaction of saying to you: We have helped and directed you, we have caused abundance to be substituted for scarcity, liberty for slavery, and happiness for misery.

Bless, then, the God of destinies, who has deigned to look with compassion upon his people!

[1] and [3]: Without changes, same as OTL.

[2]: Although the number and general composition of the Articles is the same as OTL, there has been some changes for them to fit ITTL.

Last edited:

The Republican-Monarchist Question, Part 3: The "Feelings of the Nation"

Excerpt from the chapter "Morelos: from monarchism to republican Jacobinism" available in "Detailed History of Mexico: Volume II", by multiple authors:

When Morelos read Mr. Rayón's Constitutional Elements, he found himself with a mixture of emotions: on the one hand, he was fascinated by some of the articles of the Elements, especially those concerning the division of powers, the protection of the Catholic Church, and the question of popular/national sovereignty. However, in addition to the obvious sense of envy he felt, he was particularly dissatisfied with the royal question. After all, as an antecedent, when the insurgent forces were pacifying Mexico City after its fall, news of the Fall of Cadiz at French hands arrived (around April-May). Due to Morelos' absence in Mexico City at the time, he did not receive the news until July, while he was in Chilpancingo, attempting to capture Acapulco. Although the effect was demoralizing in general, Morelos felt that his detached stance from the monarchy was only further justified: in a letter to his comrades (namely, Hidalgo, Rayón and Hermenegildo Galeana, who would become Morelos' "left arm"), he would offer a negative outlook regarding the possibility of the Spanish monarchy surviving, at least the legitimate monarchy:

"Dear brothers, I have heard of the events in the Peninsula and of the unsuccessful efforts of the Peninsular Armada to reconquer the city of Cadiz. I am aware that surely the rest of you must be upset or saddened by such news, as I am myself. However, my spirit commands me to go on and walk, because our fight against the gachupines is an honest fight. Therefore, brothers, open your eyes, because our victory is ours for the taking! With the help of Almighty God and Our Lady of Guadalupe we will be able to bring happiness and well-being to all the peoples of America. And we will be free with or without Spain, because there is no more Spain, because the French have taken it over. There is no Ferdinand VII, because either he wanted to go to his house of Bourbon to France, and then we are not obliged to recognize him as king, or he is arrested or dead, and no longer exists. Brethren, I ask you not to give up in sadness, because our aim remains the same. It is as lawful for a conquered kingdom as it is for Spain to reconquer itself, as it is lawful for an obedient kingdom not to obey its king or its monarchy. Therefore, it is lawful for us to continue without Spain, because Spain is our brother, not our master, and our America should not be the slave of any nation. [1]

Chilpancingo, October 9, 1811".

Morelos would return to Mexico City to be part of the Supreme Junta, and later, to rival Rayón on the royal question. Having made his own personal observations, he, Hermenegildo, and Mariano Matamoros, his future "right arm", were drafting their own document as a counter-response (and, to some extent, complement) to Rayón's Constitutional Elements. It would take them 5 months to bring it out, due to the obligations of the civil war (and diplomacy with the United States, already in its own conflict). An important point to note is that there is no historical evidence to support that Rayón and Morelos had any enmity. It is not that neither of them hated each other, as some historians have claimed; on the contrary, they respected each other. But respect does not necessarily imply similarity of opinion. After the death of Hidalgo and [REDACTED], both characters reconnected, in favor of the republican cause.

Hermenegildo Galeana and Mariano Matamoros, close allies of Morelos.

Morelos, Hermenegildo and Mariano drafted together the so-called "Documento Constitucional Provisional para la Independencia de la América Mexicana" (Provisional Constitutional Document for the Independence of Mexican America), being sent to Hidalgo on September 14, 1812 for his reading, approval or modification. Each Captain of the Supreme Junta received a copy of the same document for review and debate. After the Independence, and with the formation of new Constitutions, the document began to be called "Sentimientos de la Nación" (Feelings of the Nation), based on Morelos' own comments on it, which appealed to the fact that "what is written here represents what our America requires, to consolidate itself as a free and sovereign Nation".

The document has no introduction or epilogue, only the Articles, a total of 21. Morelos initially intended to make 23, but on the advice of his protégé, Carlos Maria de Bustamante, they were suppressed. The reasons for the suppression were never confirmed. One had to do with the ecclesiastical hierarchy (Pope, bishops and priests), and the other was simply eliminated for being redundant with respect to the division of powers. [2] The articles in question are [3]:

The document has no introduction or epilogue, only the Articles, a total of 21. Morelos initially intended to make 23, but on the advice of his protégé, Carlos Maria de Bustamante, they were suppressed. The reasons for the suppression were never confirmed. One had to do with the ecclesiastical hierarchy (Pope, bishops and priests), and the other was simply eliminated for being redundant with respect to the division of powers. [2] The articles in question are [3]:

- That America [Mexico] is free and independent of Spain and of any other nation, government or monarchy, and that it be so sanctioned, giving the world the reasons.

- That the Catholic religion shall be the only religion permitted, without toleration of others.

- All its ministers shall be supported by all and only tithes and first fruits, and the people shall pay no other obventions than those of their devotion and offerings.

- The national sovereignty is immediately derived from the people, who seek to deposit it in their representatives, dividing its powers into legislative, executive, and judicial, with the provinces electing their vocales, and these electing the others, who must be wise and probity subjects.

- The vocales shall serve for four years and shall take turns, with the oldest ones leaving to be replaced by the newly elected.

- The endowment of the vocales will be sufficient and not superfluous, and they will not exceed eight thousand (8000) pesos for the time being.

- That the jobs will be obtained only by Americans [Mexicans].

- That no foreigners will be admitted, if they are not artisans capable of instructing, free from all suspicion; or diplomats and emissaries of nations friendly to America [Mexico], in which case they will only be admitted in specific points to be agreed upon.

- That the motherland will not be entirely free and ours, as long as the government is not reformed, abating the tyrannical one, being substituted by the liberal, and driving out of our soil the Spanish enemy who has declared so much against our Nation.

- That as the good law is superior to every man, those which the Congress dictates should be such as to compel constancy and patriotism, to moderate opulence and indigence, and in such a way as to increase the wages of the poor, to improve their morals, to drive away ignorance, robbery, and theft.

- The general laws shall apply to all without exception of privileged bodies, and that these shall be so only as far as the use of their ministry is concerned.

- That in order to pass a law, it should be discussed in Congress, and decided by a plurality of votes.

- Slavery shall be forever outlawed, as shall the distinction of castes, and all shall be equal, and only vice and virtue shall distinguish one American [Mexican] from another.

- The ports will be able to free friendly foreign nations, but these will not enter the Nation no matter how friendly they may be, and there will only be ports designated for that purpose, prohibiting disembarkation in all the others, and 10 percent or other taxes on their goods.

- That each one should have his property guarded, and respect in his house as in a sacred asylum, pointing out penalties to offenders.

- That torture is forbidden and shall not be admitted under any circumstances.

- By constitutional law, the 12th day of December shall be celebrated in all towns, being dedicated to the patron saint of our freedom, Maria Santisima de Guadalupe, charging all towns with monthly devotion.

- Likewise, the 2nd of October of every year will be celebrated as the anniversary day in which the voice of Independence was raised, and our holy liberty began, for on that day the lips of the Nation opened to claim its rights and wielded its sword to be heard, always remembering the merit of the great hero, the Generalisimo don Miguel Hidalgo, and his companion don Ignacio Allende.

- Foreign troops or troops from different kingdoms will not set foot on national soil, unless in aid, in which case they will not be within the same place as the Supreme Junta.

- Expeditions outside the limits of the Nation, especially overseas, are prohibited, but those that are not of this kind will be permitted, for the propagation of the faith to our brothers in the interior of the country.

- That the infinity of tributes, duties and impositions which are most burdensome be removed, and that each individual be assessed a certain five percent of his earnings, or another equally light burden, which does not oppress so much, such as the alcabala, the estanco, the tribute and others, since with this short contribution, and the good administration of the confiscated goods, the enemy will be able to carry off the burden of the war and the fees of the employees.

Mexico City, September 13, 1812.

[1] This letter, although made by me, is partially based on an OTL letter Morelos made towards the creole people in Mexico, dated on February 23rd of 1812, in which he called for them to rebel against the gachupines [Spaniards]. The letter can be read here (in Spanish).

[2] The articles removed IOTL were the Articles 4° and 6°. The first one established the hierarchic order of the Catholic Church (Pope, bishops and priests), and the second one said that the three powers (Legislative, Executive and Judicial) were to be assigned in their respective compatible bodies to be exercised. The articles were removed by Bustamante, who was ordered by Morelos to check the document and make some modifications if needed. Unfortunately, Morelos never had the opportunity to see the modified document.

[3] As with the Constitutional Elements, the articles are basically the same as IOTL, but I modified them slightly to fit better to this TL.

[2] The articles removed IOTL were the Articles 4° and 6°. The first one established the hierarchic order of the Catholic Church (Pope, bishops and priests), and the second one said that the three powers (Legislative, Executive and Judicial) were to be assigned in their respective compatible bodies to be exercised. The articles were removed by Bustamante, who was ordered by Morelos to check the document and make some modifications if needed. Unfortunately, Morelos never had the opportunity to see the modified document.

[3] As with the Constitutional Elements, the articles are basically the same as IOTL, but I modified them slightly to fit better to this TL.

Discord Link (Offtopic)

Just as a personal update, some friends and I are making a Discord server to discuss or promote our different timelines or projects. The server is bilingual (English and Spanish) and it's meant to be a space of discussion about that TL's (including mine), offer suggestions or simply checking the development of the TL's.

I'm more active on Discord than here so if you want to contribute somehow to this timeline, criticize me or suggest me some interesting options, welcome: https://discord.gg/cRzRmj7tFN

I'm more active on Discord than here so if you want to contribute somehow to this timeline, criticize me or suggest me some interesting options, welcome: https://discord.gg/cRzRmj7tFN

chestanewmitz

Banned

I am starting to read @minifidel's story and it would be so cool if both happened at the same time

Maybe, that TL' is very good, although my focus is on Mexico, for obvious reasons (it's the protagonist country and my country). Of course, I will try to give some context on Latin America later.I am starting to read @minifidel's story and it would be so cool if both happened at the same time

Interesting tl. A more interventionist economy from mexico does sound like a logical evolution of the bourbon reforms.

The War of 1812: Prelude

Spencer Perceval was certainly not the most beloved Prime Minister. His military and political actions, although they had allowed the recovery of the British economy and armed the nation against the apparent invincibility of Napoleon and his Empire, were unpopular among the lower classes of the United Kingdom. Even before becoming PM, he had already supported laws in favor of raising taxes to finance the War against France, which logically affected the poor families of the country. His opposition to Catholic Emancipation in the UK also created disputes with other individuals and would eventually serve as an excuse for Catholic migrations to Mexico, especially in Texas and Florida, which would prove vital for the Mexican war effort years later. However, that does not detract from the fact that, in some cases, Perceval had more or less "progressive" positions for the time, such as his support for the abolition of the slave trade. In any case, his almost chauvinistic willingness to stand up to Napoleon, in the midst of the defeatism affecting the British government at the time, finally elevated him to the post of PM in 1809.

His initial government sought to continue the offensive against Napoleon from the Iberian Peninsula, on behalf of the Duke of Wellington. Likewise, he had to face the possibility of a regency in the British monarchy, as King George III was not in good health, and of which his son, the future George IV, then Prince of Wales, would become regent. The Prince was closer to the Whigs than to the Tories, so Perceval had to negotiate with the Prince to allow the government to function. Other problems of Perceval's government were related to the economic depression of the country, the pacification of Ireland and the increasingly complicated diplomatic situation with the United States. And, in spite of all this, Perceval seemed to resist and remain firm in his ideals. And not only that, but his government was consolidating more and more. And the victories in Portugal only proved that his war policy was working.

Then came the attack.

His initial government sought to continue the offensive against Napoleon from the Iberian Peninsula, on behalf of the Duke of Wellington. Likewise, he had to face the possibility of a regency in the British monarchy, as King George III was not in good health, and of which his son, the future George IV, then Prince of Wales, would become regent. The Prince was closer to the Whigs than to the Tories, so Perceval had to negotiate with the Prince to allow the government to function. Other problems of Perceval's government were related to the economic depression of the country, the pacification of Ireland and the increasingly complicated diplomatic situation with the United States. And, in spite of all this, Perceval seemed to resist and remain firm in his ideals. And not only that, but his government was consolidating more and more. And the victories in Portugal only proved that his war policy was working.

Then came the attack.

Artist's impression of the assassination attempt on Mr. Perceval.

At 5:15 p.m. on May 11, 1812, Spencer was nearly killed on his way to the House of Commons. [1] An unknown individual drew his pistol and shot Perceval. Due to the circumstances of the moment, it seems that luck smiled on the PM, as the bullet struck his shoulder, rather than his heart. In any case, he fell to the ground, and the perpetrator of the attack made his escape, only to be arrested by the police. Shortly thereafter, the name of the accused was revealed: John Bellingham. His motives for attempting to assassinate the PM were unclear, but it is now believed that Bellingham was upset at the British government's failure to compensate him for having been a prisoner of the Russian Empire years earlier. His original target was the British ambassador to Russia, but since Perceval did not have any kind of security force, it was easier to try to kill him. Unfortunately for Bellingham, his target didn't die. Worse, his ideological attitude didn't changed in the slightest. Bellingham would be executed 3 days after the attack, while the PM set himself up as a martyr. If he was intransigent before, he would be more so now, no matter what the poor or the Catholics said.

A little more than a month after the attack, on June 18, President James Madison would sign the declaration of war against the United Kingdom. News of the invasion of Canada by the U.S. government would reach London at least a month later, in July. Perceval's intransigence would be put to the test. The United Kingdom was not about to let its most important colony in North America fall, not without a fight.

A little more than a month after the attack, on June 18, President James Madison would sign the declaration of war against the United Kingdom. News of the invasion of Canada by the U.S. government would reach London at least a month later, in July. Perceval's intransigence would be put to the test. The United Kingdom was not about to let its most important colony in North America fall, not without a fight.

There is no consensus among scholars about the reasons that led President Madison to declare war on the British. The most commonly cited reason is American nationalism-expansionism, which was already beginning to manifest itself before the Indian Nations in the western United States, and which Mexico would later have to suffer. Precisely, Mexican nationalists have always tried to accept this as the main or even the only reason: the United States was an expansionist and imperialist nation. Logically, that view is partially incorrect. While it is true that the Americans were already expanding on the mainland at the expense of the Indian Nations, which sought military and economic support from the United Kingdom for their survival, it does not fully explain the Madison administration's motives for declaring war.

In general, the motives most commonly accepted by the historical community are:

In general, the motives most commonly accepted by the historical community are:

- Internal disputes in American politics: Madison's administration was led by the Democratic-Republican Party, with a Southern-Western bias, favorable to France and with conservative policies, such as a weak central government or state's rights, including the maintenance of slavery. The opposition to Madison was the Federalist Party, close to the British, with its stronghold in New England, in favor of a strong central government, and gradually against slavery, either on principle or in opposition to the "3/5 Compromise". That dispute between officialdom and opposition was beginning to affect the unity of the American nation. After all, the Federalists looked favorably on the British Monarchy, which was "punishing" the Americans for their trade with France.

- The Indian Question: The Indian Nations in the Northwest United States were forced to negotiate with the British to maintain their independence from the United States. Initially, the British government was apathetic towards them, but after the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, the British took a more defensive stance towards the Americans, and agreed to support the Indians with arms and military equipment and were even guaranteed that the British government would come to their aid in the event of a defensive war against the United States. The battle of Tippecanoe in 1811 only worsened the situation, as the British and Indians became more and more suspicious of the Americans, and vice versa. It is not strange then that when the war began, the Indian Nations allied themselves with the British.

- The seizure of U.S. merchant ships by the British and French Navy: As a result of the French naval blockades of the United Kingdom and vice versa, U.S. naval trade with both countries at the same time became almost impossible. Both governments seized U.S. ships, and in the French case, arrested their crews as war criminals. The U.S. government reacted, logically, negatively. Madison even proposed declaring war on France. In addition, both the United States and the United Kingdom levied British and American citizens living in each other's territory for naval trade purposes, which caused diplomatic conflicts between them.

- The Canadian Question: Although the idea of annexing Canada to the United States was not unanimous among the American population or politicians, there were important voices calling for the annexation of the region. The then Secretary of State, James Monroe, was in favor of annexation, believing that the invasion of Canada would serve to force the British to accept peace. Oppositions against annexation were based on anti-Catholicism, especially when Quebec was mentioned.

- U.S. support to Mexico [2]: The Treaty of Cooperation that Madison's government had signed with the government of the Supreme Junta implied U.S. de facto recognition of the Mexican insurgents, as opposed to the recognized government of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. As was expected, Spain broke off diplomatic relations with the United States, and given the mutual support between the Spanish and British as part of the efforts against Napoleon, the British government did not agree to negotiate with the insurgents in any way, just as it agreed to support Spain economically to stop the revolutionaries, at least once the situation in Europe could be stabilized. The truth is that the Americans didn't look favorably on the Mexican insurgents, but the riches from the Mexican mines (gold and silver) were necessary for the future U.S. war effort. Thus, at least indirectly, the two governments had different positions on how to deal with the revolutionaries in Mexico City.

Overall, all of these factors meant that, after the Battle of Tippecanoe, Madison was forced to make the declaration of war. And, despite all this, opposition to the war was strong. The Federalists would not stand idly by. Nor would the Democratic-Republicans.

Mexicans and Spaniards would also be spectators of a conflict that could either help them in their opposing goals or ruin their expectations.

Mexicans and Spaniards would also be spectators of a conflict that could either help them in their opposing goals or ruin their expectations.

[1] As you can expect, IOTL Mr. Perceval was killed. In fact, Perceval is the only PM to have been killed until today. It seems that luck smiled him in this world.

[2] IOTL, the Mexican War of Independence didn't affect the British-American relations, since the Americans never helped the insurgents. ITTL, it's the inverse. As you can expect, Spain will also take a somewhat more aggressive stance in the War of 1812.

[2] IOTL, the Mexican War of Independence didn't affect the British-American relations, since the Americans never helped the insurgents. ITTL, it's the inverse. As you can expect, Spain will also take a somewhat more aggressive stance in the War of 1812.

Both the Bourbon Reforms and the radical aspect of the French Revolution influenced the Mexican revolutionaries in the sense that the government was forced to bring happiness and prosperity to the population. I would say that OTL that aspect was forgotten and eliminated until the Mexican Revolution, when the new Mexican state started to be more and more interventionist, contrary to the liberal-laissez faire government of the Porfiriato. Even today, after the (neo)liberal reforms, the Mexican government is still somewhat interventionist in some aspects of the economy and labour protections.Interesting tl. A more interventionist economy from mexico does sound like a logical evolution of the bourbon reforms.

"La Tragedia"

On June 18, 1812, the United States declared war on the United Kingdom. More than a month later, the last shipment of "Kentucky" rifles arrived from New Orleans to San Antonio in Tejas, to be departed into the central provinces. The U.S. government would continue to receive Mexican gold and silver, but would not reciprocate the agreement: there would be no more arms shipments until the situation could be stabilized in the country. President Madison feared that the states governed by Federalists might declare secession and ally themselves with the British. The full force of the federal government was needed to maintain law and order in the country.

The Supreme Junta in Mexico City began to fear the worst. While it was true that they had de facto control of most of so-called continental Mexico, the situation in Cuba and Central America was different. Although there were independence movements in the Captaincy General of Guatemala, none were capable of challenging the royalist order. Another problem, which will also cause problems for the independent Mexican government, is that these movements did not seek to integrate into "Mexican America", but to form an independent, free and sovereign Central America, and not being dependent on Spain or any other country, including Mexico. As for Cuba, its independence movement was virtually non-existent, and beyond the occasional slave who had sympathies for wanting to be free of his condition, the island was loyal to Spain. With the United Kingdom supporting the Spanish in their fight against Napoleon, it was only a matter of time before the royalist troops could balance the scales.

However, the real problem in gaining effective control of the territories held by the insurgents was internal subversion. Peninsulars and certain groups of Creoles were reluctant to accept the Independence of the Mexican Nation, regardless of the modality it acquired. Not so much out of loyalty to Ferdinand VII, but for fear of losing privileges, in the case of some, or being expelled or savagely assassinated, in the case of others. Certainly, the insurgent groups were not exactly the friendliest or most inclusive when it came to peninsulares (gachupines), but neither were they so with respect to alleged informers among the ranks of the criollos. Executions for treason were nothing out of the ordinary, and in many cases the insurgent generals did not stop their subordinates from committing barbaric acts or did so too late; the case of the Alhondiga de Granaditas being the best-known case, and probably the most unfortunate too. All in all, the increasingly strong political radicalism within the Supreme Junta, as well as the unfortunate acts committed by the insurgent side, only provoked the ever-stronger alignment of peninsulars and groups of creoles to the royalist side. The case of Agustín de Iturbide is based on this: he was not particularly loyal to the Spanish monarchy, but he despised the excessive violence used by the insurgents to achieve their objectives.

Normally this would not be a problem, were it not for the fact that such subversive elements had enough influence and money to buy off larger groups of people: mestizos, Indians and slaves (with the promise of being freed) also began to gradually rebel against the Supreme Junta. Legitimacy was being lost. Families were being divided. Children started to become orphan as a result of the deaths of their parents. Hidalgo himself recalls in his memoirs having nightmares at the mere thought of knowing that, under his rule, hundreds or even thousands of people were being killed, both insurgents and royalists. He did not want this. He wanted a better government than before. Shortly before "La Tragedia" he confessed to having trouble sleeping. Little by little he spent less and less time in government. He was still the Generalisimo, but in practice it was the Captains who were in charge of administering the governmental tasks, in front of a dejected Hidalgo, old and fearful of God's wrath. In his mind, even if he was fighting for a just cause, his hands were stained with blood, and he would have to suffer the greatest condemnation of all: Hell.

The other insurgent leaders were not very optimistic about the situation either. They could face a conventional war now that they had the capital under their control, but the royalists were applying a war of attrition, and it was working. Something had to be done to deliver the coup de grace to the Spanish, and it had to be done now. The fall of Acapulco at the hands of Morelos' troops had yielded satisfactory results, but the biggest prize was in Veracruz. The port of Veracruz was constantly supplied from Cuba, and the land and sea defenses made Veracruz a fortress city. In addition, in the absence of the Viceroy, a military council led by the wounded, but alive and more determined than ever Felix Maria Calleja, ruled the city in preparation for an offensive on Mexico City. Although the insurgents had more troops, the royalist troops in Veracruz were la crème de la crème, the novo-Hispanic military elite. First-rate Spanish weapons, discipline and constant supplies could make the difference, contrary to the mostly unarmed insurgent troops, who, although numerous, were composed of conscripted troops: peasants, free slaves, mine workers, children, etc. Different people who shared a characteristic: they were not soldiers. They were not even trained in the most basic military settings. Some of them didn't even spoke Spanish, since they were educated in their native languages.

The insurgent leaders had to capture Veracruz before the situation in Spain stabilized. If they did not, it would be the end. Calleja was enemy number one, if he died, perhaps the royalist effort could collapse, and Mexico could finally be free. Aldama said that "If Mexico wants to survive this war, we cannot do it with Calleja on the field" [1]. Therefore, the strategy of the Supreme Junta was a massive offensive on all possible points to Veracruz. A desperate effort to gain legitimacy, strength, and, above all, to finally negotiate the end of the war. Over 30,000 insurgent troops, both well-armed and cannon fodder, were prepared. Although most of Veracruz could be captured without too much trouble, the port of San Juan de Ulua, as well as other walled constructions on the shores of the city and the port were the priority. It had to be a quick, precise operation, from which no reinforcements could be sent from Cuba. In short, it had to be the battle that would end the war.

The Supreme Junta in Mexico City began to fear the worst. While it was true that they had de facto control of most of so-called continental Mexico, the situation in Cuba and Central America was different. Although there were independence movements in the Captaincy General of Guatemala, none were capable of challenging the royalist order. Another problem, which will also cause problems for the independent Mexican government, is that these movements did not seek to integrate into "Mexican America", but to form an independent, free and sovereign Central America, and not being dependent on Spain or any other country, including Mexico. As for Cuba, its independence movement was virtually non-existent, and beyond the occasional slave who had sympathies for wanting to be free of his condition, the island was loyal to Spain. With the United Kingdom supporting the Spanish in their fight against Napoleon, it was only a matter of time before the royalist troops could balance the scales.

However, the real problem in gaining effective control of the territories held by the insurgents was internal subversion. Peninsulars and certain groups of Creoles were reluctant to accept the Independence of the Mexican Nation, regardless of the modality it acquired. Not so much out of loyalty to Ferdinand VII, but for fear of losing privileges, in the case of some, or being expelled or savagely assassinated, in the case of others. Certainly, the insurgent groups were not exactly the friendliest or most inclusive when it came to peninsulares (gachupines), but neither were they so with respect to alleged informers among the ranks of the criollos. Executions for treason were nothing out of the ordinary, and in many cases the insurgent generals did not stop their subordinates from committing barbaric acts or did so too late; the case of the Alhondiga de Granaditas being the best-known case, and probably the most unfortunate too. All in all, the increasingly strong political radicalism within the Supreme Junta, as well as the unfortunate acts committed by the insurgent side, only provoked the ever-stronger alignment of peninsulars and groups of creoles to the royalist side. The case of Agustín de Iturbide is based on this: he was not particularly loyal to the Spanish monarchy, but he despised the excessive violence used by the insurgents to achieve their objectives.

Normally this would not be a problem, were it not for the fact that such subversive elements had enough influence and money to buy off larger groups of people: mestizos, Indians and slaves (with the promise of being freed) also began to gradually rebel against the Supreme Junta. Legitimacy was being lost. Families were being divided. Children started to become orphan as a result of the deaths of their parents. Hidalgo himself recalls in his memoirs having nightmares at the mere thought of knowing that, under his rule, hundreds or even thousands of people were being killed, both insurgents and royalists. He did not want this. He wanted a better government than before. Shortly before "La Tragedia" he confessed to having trouble sleeping. Little by little he spent less and less time in government. He was still the Generalisimo, but in practice it was the Captains who were in charge of administering the governmental tasks, in front of a dejected Hidalgo, old and fearful of God's wrath. In his mind, even if he was fighting for a just cause, his hands were stained with blood, and he would have to suffer the greatest condemnation of all: Hell.

The other insurgent leaders were not very optimistic about the situation either. They could face a conventional war now that they had the capital under their control, but the royalists were applying a war of attrition, and it was working. Something had to be done to deliver the coup de grace to the Spanish, and it had to be done now. The fall of Acapulco at the hands of Morelos' troops had yielded satisfactory results, but the biggest prize was in Veracruz. The port of Veracruz was constantly supplied from Cuba, and the land and sea defenses made Veracruz a fortress city. In addition, in the absence of the Viceroy, a military council led by the wounded, but alive and more determined than ever Felix Maria Calleja, ruled the city in preparation for an offensive on Mexico City. Although the insurgents had more troops, the royalist troops in Veracruz were la crème de la crème, the novo-Hispanic military elite. First-rate Spanish weapons, discipline and constant supplies could make the difference, contrary to the mostly unarmed insurgent troops, who, although numerous, were composed of conscripted troops: peasants, free slaves, mine workers, children, etc. Different people who shared a characteristic: they were not soldiers. They were not even trained in the most basic military settings. Some of them didn't even spoke Spanish, since they were educated in their native languages.

The insurgent leaders had to capture Veracruz before the situation in Spain stabilized. If they did not, it would be the end. Calleja was enemy number one, if he died, perhaps the royalist effort could collapse, and Mexico could finally be free. Aldama said that "If Mexico wants to survive this war, we cannot do it with Calleja on the field" [1]. Therefore, the strategy of the Supreme Junta was a massive offensive on all possible points to Veracruz. A desperate effort to gain legitimacy, strength, and, above all, to finally negotiate the end of the war. Over 30,000 insurgent troops, both well-armed and cannon fodder, were prepared. Although most of Veracruz could be captured without too much trouble, the port of San Juan de Ulua, as well as other walled constructions on the shores of the city and the port were the priority. It had to be a quick, precise operation, from which no reinforcements could be sent from Cuba. In short, it had to be the battle that would end the war.

The Battle of Veracruz, also known as "La Tragedia." [2]

Instead, it became a massacre. The Battle of Veracruz began on October 6, 1812 and ended a couple of weeks later. In Mexican Collective History, it would be remembered as "La Tragedia" (The Tragedy), due to the large number of insurgent troops killed. Around 20,000 to 24,000 of the insurgent troops were killed or captured, against a total loss of 1,300 of the 15,000 royalist troops that defended the city. The royalist strategy was somewhat simplistic but worked: most of the city was gonna abandoned to the insurgent troops, but the populace was going to disrupt the advance of the insurgents meanwhile the Spanish Army gained time to install their artillery, cannons and different kind of fireweapons, both Spanish and British. Once the insurgents finally managed to enter the center of city, the Spanish troops launched all the artillery they had to kill the cannon fodder of the insurgents. The civilian populace, who was also loyal to the Spanish (mostly because of fear than of actual loyalty), helped to encircle some of the insurgent troops in the center of the city, which allowed the royalists to deal with them. The remnants of the insurgents in the city were allowed to surrender and pledge loyalty to Calleja, as an exchange to not be executed. The ones who were in the outskirts of the city decided to escape and return to Mexico City to inform of the complete failure of the operation. Since the Spanish had some navies to defend the Fort of San Juan de Ulua, there was no possibility of the insurgents to reach the fort and the port. Contrary to the royalists, they didn't had a naval force.

When the battle finally ended, the Zocalo of the city smelled to Death. What was worse, the insurgent general and Father of the Nation, Ignacio Allende, who was among the military leaders of the battle, had been wounded and captured. He would not return alive. Modern historians agree that he was tortured and finally killed. With a good contingent of insurgent troops dead, Calleja saw his chance. Much of the defenses toward Mexico City were now dead or wounded, unable to help to the defence of the city. Calleja thought the situation was somewhat similar to 1519, when Hernán Cortés founded Veracruz, and later headed for Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Mexica Empire, to finally conquer it in the name of God, the King and Hispanidad. Calleja would be the Second Cortés, the one who would lead his loyal men to the capital of the Viceroyalty and destroy the enemies of Spain, led by the heretic Hidalgo.

The latter's days were numbered.

[1] I hope someone of you understand the reference.

[2] AI-generated art, again. Have in mind that, considering the circumstances, this will become more common if necessary. I hope it's not a motive of trouble, considering the whole polemic about AI-generated images.

[2] AI-generated art, again. Have in mind that, considering the circumstances, this will become more common if necessary. I hope it's not a motive of trouble, considering the whole polemic about AI-generated images.

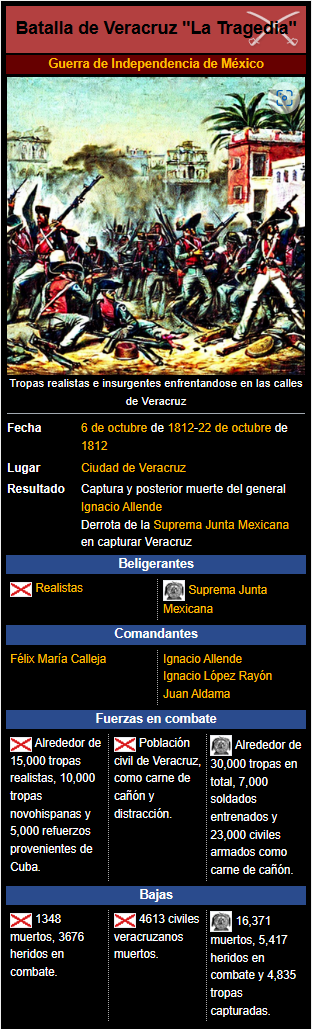

La Tragedia: Wikibox

I decided to make the first Wikibox for this TL, with La Tragedia as the protagonist battle for that matter. The Wikibox is in Spanish for lore reasons (I think), but it should be understandable. I would like to know if you like this Wikibox format or do you want the OTL Wikipedia colour format (also, if you want to have an English version, let me know).

Last edited:

Oh boy, so it seems things must get worse for the insurgents before they get better. Losing Allende will also be a big blow to the cause and it seems Hidalgo should follow soon enough, which will mark a considerable shift in the leadership of the Junta. Given what we have read so far about the future of Mexico, it wouldn't surprise that Morelos and his allies, specially after the capture of Acapulco, will become the new faces of the movement.

Related to this, could we see Morelos and his veteran army riding hard from Acapulco towards CDMX in an attempt to save the city from falling to Calleja?

Related to this, could we see Morelos and his veteran army riding hard from Acapulco towards CDMX in an attempt to save the city from falling to Calleja?

Yes, you are actually right on how I want to get things done for the Independence! I'm using how the movement evolved OTL to justify why Hidalgo must die: the Independence OTL is generally divided in 4 stages: Start of the war, Organization, Resistance and End. The first one, the start, was led by Hidalgo and Co., and ended when he died, and Morelos became the de facto leader of the movement. The second stage was led by Morelos and Co. and saw how the movement evolved from how Hidalgo wanted the movement to be (constitutional monarchy/provisional government in absence of Ferdinand VII) to an actual independentist movement (and the formation of a Republic). Morelos learned from the mistakes committed by Hidalgo and other earlier leaders, so the Organization stage was the most successful one for the Independence, until Morelos died, and the Independentist movement almost collapsed (the Resistance stage).Oh boy, so it seems things must get worse for the insurgents before they get better. Losing Allende will also be a big blow to the cause and it seems Hidalgo should follow soon enough, which will mark a considerable shift in the leadership of the Junta. Given what we have read so far about the future of Mexico, it wouldn't surprise that Morelos and his allies, specially after the capture of Acapulco, will become the new faces of the movement.

Related to this, could we see Morelos and his veteran army riding hard from Acapulco towards CDMX in an attempt to save the city from falling to Calleja?

In this case, something similar will happen: the death of Hidalgo (an unfortunate one, by the case) will cause Morelos to finally rise, and fix the mistakes committed originally. Hidalgo dying will unite the Junta to seek a common goal, of course, but will also alienates it towards Morelos' project, which is the establishment of the Republic.

The only difference I want to modify is Hidalgo dying heroically, or at least in a more heroic way than OTL. That way he will be a martyr.

Finally, yes, kind of. Morelos should be already at Mexico City when the time to defend the city comes.

EDIT: I see that you are fellow mexican, Bienvenido!

Last edited:

Sacrifice

Review: "Gritos de muerte y libertad" by Guillermo del Toro, 2010, Mexico:

"Our Independence" (Nuestra Independencia), also called "Cries of Death and Freedom" (Gritos de muerte y libertad), is a dramatized historical documentary that narrates the events concerning Mexico's Independence. Directed by the famous Mexican actor, filmmaker, screenwriter and director Guillermo del Toro, the documentary narrates through different chapters the events concerning the War of Independence, under a touch of drama to give the viewer some extra emotion. The documentary was released on October 2, 2010, the bicentennial of the Grito of Queretaro, which marked the beginning of the War of Independence.

Given its character as a documentary, each of the seasons had a few extensive episodes of at least one hour each one, in which different moments of the Independence are narrated, using public and private historical documents, in an attempt to offer the viewer, the most complete view of the events that took place 200 years ago. The 1st season narrates the historical background of the Independence, from the birth of the Creole identity in New Spain, the American and French Revolutions, the French invasion of Spain in 1808, and finally, the Grito of Queretaro. The 2nd season begins with the arming of the insurgent army, the constant battles that took place until the capture of Mexico City, the internal disputes in the Supreme Mexican Junta, the realist rearmament, "La Tragedia" and the tragic events of the death of the priest Hidalgo, as well as the desperate resistance of the insurgents to avoid the collapse of the insurgent government. The 3rd season narrates the consolidation of republicanism, the proclamation of the Mexican Republic, the events of [REDACTED]...until the republican victory and the annexation of Central America.

Although realism is respected as much as possible in all three seasons, it is well known that Del Toro always tries to offer works that are both respectable and interesting. Some other critics or purist viewers take this element of drama in the documentary as a problem, considering that events that historically were rather calm are shown in a much more active way in the documentary. However, the general consensus, myself included, is that the production of the documentary is very well done; for example, the uniforms worn by the royalists and insurgents are considered historically accurate, as are the weapons and troop organization. Del Toro also tries to highlight the figure of historically forgotten or neglected characters, such as Josefa Ortiz de Dominguez, Victor Rosales or Epigmenio Gonzalez. An important element is the dynamic use of the cameras, instead of a static shot, which gives more interest and development to the documentary.

My personal recommendation: Del Toro did it again, a true work of art. Although there may be certain moments that may be confusing to a non-historical individual, to any Mexican patriot it will seem like an accurate representation of the War of Independence. As a curious thing, apparently the most watched episode was the one related to the death of the priest Hidalgo, which is in the Mexican national collective as the definitive moment where all possibility of conciliation with Spain was broken. The episode was watched in its first broadcast by almost 4 million people at the same time, a real success in terms of ratings. However, I would have liked Del Toro to have delved more into Hidalgo's final letters, and the torture of Allende at the hands of Calleja, as an antecedent to the priest's death.

10/10. I would watch it again.

The situation was in extreme chaos in Mexico City. The remnants of the demoralized Army that fought in Veracruz had barely managed to reach the capital alive. Meanwhile, Allende was tortured to give information that could help the royalist effort...but he did not yield. Perhaps one of Hidalgo's few misjudgments of his comrade-in-arms was his loyalty: after all, they had many run-ins during the early days of the insurgent movement. But Allende, who like every human being was flawed, was not a traitor. He did not betray his comrades, and although he was not exactly Hidalgo's friend, he had respect for him. He was executed by firing squad, and his body was beheaded. Unfortunately, there are no records of his last words, although historical accounts state that he died with his head held high, with no sign of fear of death.

To make matters more difficult, there were rumors of peninsular and Creole groups conspiring to organize an uprising to surrender the city to Calleja, reinstate the Viceroy and crush the Supreme Junta. It is no exaggeration to say that, for a moment, it looked like the end. Even with control of Mexico City, the insurgent government had shown itself to be incompetent, ineffective. Calleja was no fool, he knew that to reach the capital he had to first pass through Puebla, and he would have to amass a good number of men to do the job, no matter if they were Spaniards, Creoles, mestizos or Indians. All that mattered was that they needed to break down the defenses of Puebla to have open access to the capital. Likewise, the insurgent government tried to focus all its resources on the capital and its defense, even if it meant the loss of towns in other regions to the royalists. It was clear to both sides that they had to go for the jackpot: all or nothing, to victory.

Hidalgo had had enough. Enough of so many defeats. Enough of the factional disputes. Enough of having to deal with the weight of his sins on his shoulders. He was tired, old, and his role as Generalissimo was only making him weaker and weaker. The question was not if he was going to die, the question was how he was going to die. The other generals were younger, they could be better leaders than him. They could better manage the rebel effort than he could. He knew that. Then came the news of Allende's death, and he didn't take it well. All he wanted was to be alone. He had not given up hope of winning, but simply the emotional pain and stress were beyond his limit. Meanwhile, Morelos and Rayón temporarily abandoned their ideological disputes to try to bring order to the capital. The hours felt like days as the situation seemed to degenerate. Although arrests were continually being made, there was no improvement in the mood of the revolutionaries. The nightmares did not cease. Hidalgo let a good man die. Allende was not very friendly with him, but he died without betraying his movement. Just imagining what atrocities they inflicted on him to try to get him to talk only worsened the priest's already delicate mental health. The Supreme Junta had effectively collapsed, and its members were preparing for the worst. Pro-independence Creoles were leaving the city en masse to try to save themselves from battle and prepare for another day. The inhabitants, the common people, the lifelong civilians, were afraid. Some had aided the rebellion, and the rest simply accepted the new status quo. Nothing good was in store for them. It would seem that only a divine miracle could solve things. Hidalgo saw the suffering that was to come, and, for a brief moment, he saw the light of the sun.

He understood what he needed to do.

Puebla began to be attacked and besieged at the end of November. Morelos and Rayón prepared to go and defend her, but something unprecedented happened: the Generalisimo was gone, he came to the aid of the attacked city. To this day, there is no clear motive for the motivations of a depressed Hidalgo for wanting to lead the defense force of the city of Puebla: the motives vary from his mental health that derived in a momentary attack of madness, or his remorse for not having helped Allende in Veracruz. Be that as it may, Hidalgo ordered his subordinate generals to prepare for the defense of the capital, because it was inevitable that Puebla would fall, since the Valley of Atrisco (Atlixco) was captured by the royalist troops, and there was no possibility of feeding a besieged city that had lost its agricultural valley. As a whole, Hidalgo decided to defend an indefensible city... He went to die voluntarily, to gain time. Perhaps he could not redeem himself for his sins. But he would do the impossible to avenge the fallen in this war, which was a just war in his eyes. He was not a good general, because after all he was not a military man, but by being the Maximum Chief, he was charismatic and gave hope to others in times of desperation. His anti-slavery, anti-castes, religious but at the same time modern message was captivating. For the priest, the movement could not advance with him at the forefront. Morelos, Rayón, Aldama; and all the others, all of them would be the ones to liberate Mexico, Anahuac, or whatever the future country was to be called. In his last letter to his generals, he made his instructions clear: