Capitulum I: The Italian Peninsula in 1836

Italy was unified by Rome in the third century BC. For 700 years, it was a de facto territorial extension of the capital of the Roman Republic and Empire, and for a long time experienced a privileged status but was not converted into a province.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Italy remained united under the Ostrogothic Kingdom and later disputed between the Kingdom of the Lombards and the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. Following conquest by the Frankish Empire, the title of King of Italy merged with the office of Holy Roman Emperor. However, the emperor was an absentee German-speaking foreigner who had little concern for the governance of Italy as a state; as a result, Italy gradually developed into a system of city-states. Southern Italy, however, was governed by the long-lasting Kingdom of Sicily or Kingdom of Naples, which had been established by the Normans. Central Italy was governed by the Pope as a temporal kingdom known as the Papal States.

This situation persisted through the Renaissance but began to deteriorate with the rise of modern nation-states in the early modern period. Italy, including the Papal States, then became the site of proxy wars between the major powers, notably the Holy Roman Empire (including Austria), Spain, and France.

Harbingers of national unity appeared in the treaty of the Italic League, in 1454, and the 15th-century foreign policy of Cosimo De Medici and Lorenzo De Medici. Leading Renaissance Italian writers Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Machiavelli and Guicciardini expressed opposition to foreign domination. Petrarch stated that the "ancient valour in Italian hearts is not yet dead" in Italia Mia. Machiavelli later quoted four verses from Italia Mia in The Prince, which looked forward to a political leader who would unite Italy "to free her from the barbarians".

The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 formally ended the rule of the Holy Roman Emperors in Italy. However, the Spanish branch of the Habsburg dynasty, another branch of which provided the Emperors, continued to rule most of Italy down to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14).

A sense of Italian national identity was reflected in Gian Rinaldo Carli's Della Patria degli Italiani, written in 1764. It told how a stranger entered a café in Milan and puzzled its occupants by saying that he was neither a foreigner nor a Milanese. "'Then what are you?' they asked. 'I am an Italian,' he explained."

The Habsburg rule in Italy came to an end with the campaigns of the French Revolutionaries in 1792–97, when a series of client republics were set up. In 1806, the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved by the last emperor, Francis II, after its defeat by Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz. The Italian campaigns of the French Revolutionary Wars destroyed the old structures of feudalism in Italy and introduced modern ideas and efficient legal authority; it provided much of the intellectual force and social capital that fueled unification movements for decades after it collapsed in 1814. The French Republic spread republican principles, and the institutions of republican governments promoted citizenship over the rule of the Bourbons and Habsburgs and other dynasties. The reaction against any outside control challenged Napoleon Bonaparte's choice of rulers. As Napoleon's reign began to fail, the rulers he had installed tried to keep their thrones (among them Eugène de Beauharnais, viceroy of Italy, and Joachim Murat, king of Naples) further feeding nationalistic sentiments. Beauharnais tried to get Austrian approval for his succession to the new Kingdom of Italy, and on 30 March 1815, Murat issued the Rimini Proclamation, which called on Italians to revolt against their Austrian occupiers.

After Napoleon fell, the Congress of Vienna (1814–15) restored the pre-Napoleonic patchwork of independent governments. Italy was again controlled largely by the Austrian Empire and the Habsburgs, as they directly controlled the predominantly Italian-speaking northeastern part of Italy and were, together, the most powerful force against unification.

An important figure of this period was Francesco Melzi d'Eril, serving as vice-president of the Napoleonic Italian Republic (1802–1805) and consistent supporter of the Italian unification ideals that would lead to the Italian Risorgimento shortly after his death. Meanwhile, artistic and literary sentiment also turned towards nationalism; Vittorio Alfieri, Francesco Lomonaco and Niccolò Tommaseo are generally considered three great literary precursors of Italian nationalism, but the most famous of proto-nationalist works was Alessandro Manzoni's I promessi sposi (The Betrothed), widely read as a thinly veiled allegorical critique of Austrian rule. Published in 1827 and extensively revised in the following years, the 1840 version of I Promessi Sposi used a standardized version of the Tuscan dialect, a conscious effort by the author to provide a language and force people to learn it.

Exiles dreamed of unification. Three ideals of unification appeared. Vincenzo Gioberti, a Piedmontese priest, had suggested a confederation of Italian states under leadership of the Pope in his 1842 book Of the Moral and Civil Primacy of the Italians. Pope Pius IX at first appeared interested but he turned reactionary and led the battle against liberalism and nationalism.

Giuseppe Mazzini and Carlo Cattaneo wanted the unification of Italy under a federal republic, which proved too extreme for most nationalists. The middle position was proposed by Cesare Balbo (1789–1853) as a confederation of separate Italian states led by Piedmont.

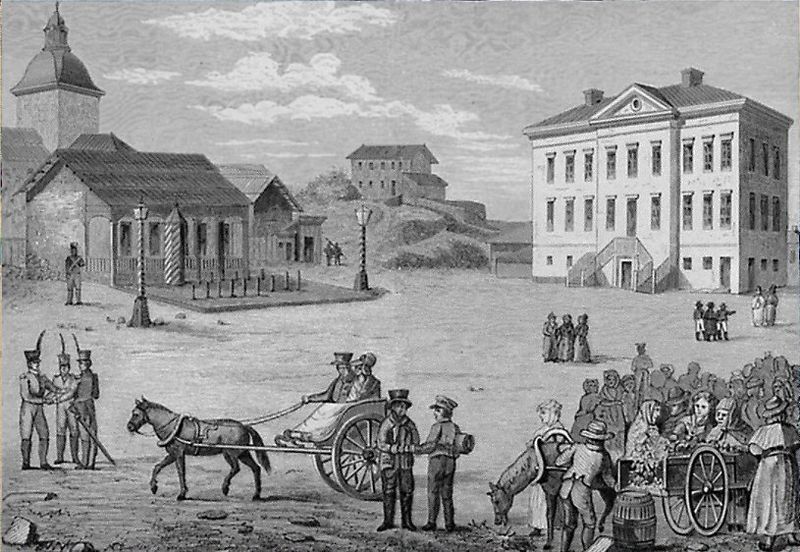

Italy in 1836

One of the most influential revolutionary groups was the Carboneria, a secret political discussion group formed in Southern Italy early in the 19th century; the members were called Carbonari. After 1815, Freemasonry in Italy was repressed and discredited due to its French connections. A void was left that the Carboneria filled with a movement that closely resembled Freemasonry but with a commitment to Italian nationalism and no association with Napoleon and his government. The response came from middle-class professionals and businessmen and some intellectuals. The Carboneria disowned Napoleon but nevertheless were inspired by the principles of the French Revolution regarding liberty, equality and fraternity. They developed their own rituals, and were strongly anticlerical. The Carboneria movement spread across Italy.

Conservative governments feared the Carboneria, imposing stiff penalties on men discovered to be members. Nevertheless, the movement survived and continued to be a source of political turmoil in Italy from 1820 until after unification. The Carbonari condemned Napoleon III (who, as a young man, had fought on their side) to death for failing to unite Italy. Many leaders of the unification movement were at one time or other members of this organization. The chief purpose was to defeat tyranny and to establish constitutional government. Though contributing some service to the cause of Italian unity, historians such as Cornelia Shiver doubt that their achievements were proportional to their pretensions.

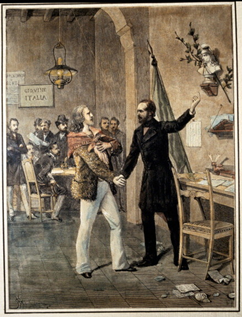

The first meeting between Garibaldi and Mazzini at the headquarters of Young Italy in 1833

Many leading Carbonari revolutionaries wanted a republic, two of the most prominent being Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi. Mazzini's activity in revolutionary movements caused him to be imprisoned soon after he joined. While in prison, he concluded that Italy could − and therefore should − be unified, and he formulated a program for establishing a free, independent, and republican nation with Rome as its capital. Following his release in 1831, he went to Marseille in France, where he organized a new political society called La Giovine Italia (Young Italy), whose motto was "Dio e Popolo" (God and People), which sought the unification of Italy.

Garibaldi, a native of Nice (then part of Piedmont), participated in an uprising in Piedmont in 1834 and was sentenced to death. He escaped to South America, though, spending fourteen years in exile, taking part in several wars, and learning the art of guerrilla warfare before his return to Italy in 1848.

I hope you guys like this new update! Be sure to like(if you like it), comment(please comment so I can learn what your opinion is) and.....follow I guess.

Italy was unified by Rome in the third century BC. For 700 years, it was a de facto territorial extension of the capital of the Roman Republic and Empire, and for a long time experienced a privileged status but was not converted into a province.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Italy remained united under the Ostrogothic Kingdom and later disputed between the Kingdom of the Lombards and the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. Following conquest by the Frankish Empire, the title of King of Italy merged with the office of Holy Roman Emperor. However, the emperor was an absentee German-speaking foreigner who had little concern for the governance of Italy as a state; as a result, Italy gradually developed into a system of city-states. Southern Italy, however, was governed by the long-lasting Kingdom of Sicily or Kingdom of Naples, which had been established by the Normans. Central Italy was governed by the Pope as a temporal kingdom known as the Papal States.

This situation persisted through the Renaissance but began to deteriorate with the rise of modern nation-states in the early modern period. Italy, including the Papal States, then became the site of proxy wars between the major powers, notably the Holy Roman Empire (including Austria), Spain, and France.

Harbingers of national unity appeared in the treaty of the Italic League, in 1454, and the 15th-century foreign policy of Cosimo De Medici and Lorenzo De Medici. Leading Renaissance Italian writers Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Machiavelli and Guicciardini expressed opposition to foreign domination. Petrarch stated that the "ancient valour in Italian hearts is not yet dead" in Italia Mia. Machiavelli later quoted four verses from Italia Mia in The Prince, which looked forward to a political leader who would unite Italy "to free her from the barbarians".

The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 formally ended the rule of the Holy Roman Emperors in Italy. However, the Spanish branch of the Habsburg dynasty, another branch of which provided the Emperors, continued to rule most of Italy down to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14).

A sense of Italian national identity was reflected in Gian Rinaldo Carli's Della Patria degli Italiani, written in 1764. It told how a stranger entered a café in Milan and puzzled its occupants by saying that he was neither a foreigner nor a Milanese. "'Then what are you?' they asked. 'I am an Italian,' he explained."

The Habsburg rule in Italy came to an end with the campaigns of the French Revolutionaries in 1792–97, when a series of client republics were set up. In 1806, the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved by the last emperor, Francis II, after its defeat by Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz. The Italian campaigns of the French Revolutionary Wars destroyed the old structures of feudalism in Italy and introduced modern ideas and efficient legal authority; it provided much of the intellectual force and social capital that fueled unification movements for decades after it collapsed in 1814. The French Republic spread republican principles, and the institutions of republican governments promoted citizenship over the rule of the Bourbons and Habsburgs and other dynasties. The reaction against any outside control challenged Napoleon Bonaparte's choice of rulers. As Napoleon's reign began to fail, the rulers he had installed tried to keep their thrones (among them Eugène de Beauharnais, viceroy of Italy, and Joachim Murat, king of Naples) further feeding nationalistic sentiments. Beauharnais tried to get Austrian approval for his succession to the new Kingdom of Italy, and on 30 March 1815, Murat issued the Rimini Proclamation, which called on Italians to revolt against their Austrian occupiers.

After Napoleon fell, the Congress of Vienna (1814–15) restored the pre-Napoleonic patchwork of independent governments. Italy was again controlled largely by the Austrian Empire and the Habsburgs, as they directly controlled the predominantly Italian-speaking northeastern part of Italy and were, together, the most powerful force against unification.

An important figure of this period was Francesco Melzi d'Eril, serving as vice-president of the Napoleonic Italian Republic (1802–1805) and consistent supporter of the Italian unification ideals that would lead to the Italian Risorgimento shortly after his death. Meanwhile, artistic and literary sentiment also turned towards nationalism; Vittorio Alfieri, Francesco Lomonaco and Niccolò Tommaseo are generally considered three great literary precursors of Italian nationalism, but the most famous of proto-nationalist works was Alessandro Manzoni's I promessi sposi (The Betrothed), widely read as a thinly veiled allegorical critique of Austrian rule. Published in 1827 and extensively revised in the following years, the 1840 version of I Promessi Sposi used a standardized version of the Tuscan dialect, a conscious effort by the author to provide a language and force people to learn it.

Exiles dreamed of unification. Three ideals of unification appeared. Vincenzo Gioberti, a Piedmontese priest, had suggested a confederation of Italian states under leadership of the Pope in his 1842 book Of the Moral and Civil Primacy of the Italians. Pope Pius IX at first appeared interested but he turned reactionary and led the battle against liberalism and nationalism.

Giuseppe Mazzini and Carlo Cattaneo wanted the unification of Italy under a federal republic, which proved too extreme for most nationalists. The middle position was proposed by Cesare Balbo (1789–1853) as a confederation of separate Italian states led by Piedmont.

Italy in 1836

One of the most influential revolutionary groups was the Carboneria, a secret political discussion group formed in Southern Italy early in the 19th century; the members were called Carbonari. After 1815, Freemasonry in Italy was repressed and discredited due to its French connections. A void was left that the Carboneria filled with a movement that closely resembled Freemasonry but with a commitment to Italian nationalism and no association with Napoleon and his government. The response came from middle-class professionals and businessmen and some intellectuals. The Carboneria disowned Napoleon but nevertheless were inspired by the principles of the French Revolution regarding liberty, equality and fraternity. They developed their own rituals, and were strongly anticlerical. The Carboneria movement spread across Italy.

Conservative governments feared the Carboneria, imposing stiff penalties on men discovered to be members. Nevertheless, the movement survived and continued to be a source of political turmoil in Italy from 1820 until after unification. The Carbonari condemned Napoleon III (who, as a young man, had fought on their side) to death for failing to unite Italy. Many leaders of the unification movement were at one time or other members of this organization. The chief purpose was to defeat tyranny and to establish constitutional government. Though contributing some service to the cause of Italian unity, historians such as Cornelia Shiver doubt that their achievements were proportional to their pretensions.

The first meeting between Garibaldi and Mazzini at the headquarters of Young Italy in 1833

Many leading Carbonari revolutionaries wanted a republic, two of the most prominent being Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi. Mazzini's activity in revolutionary movements caused him to be imprisoned soon after he joined. While in prison, he concluded that Italy could − and therefore should − be unified, and he formulated a program for establishing a free, independent, and republican nation with Rome as its capital. Following his release in 1831, he went to Marseille in France, where he organized a new political society called La Giovine Italia (Young Italy), whose motto was "Dio e Popolo" (God and People), which sought the unification of Italy.

Garibaldi, a native of Nice (then part of Piedmont), participated in an uprising in Piedmont in 1834 and was sentenced to death. He escaped to South America, though, spending fourteen years in exile, taking part in several wars, and learning the art of guerrilla warfare before his return to Italy in 1848.

I hope you guys like this new update! Be sure to like(if you like it), comment(please comment so I can learn what your opinion is) and.....follow I guess.

Last edited: