You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The March of Time - 20th Century History

- Thread starter Karelian

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."Thank you, it is always nice to know what people actually think of the text and story itself. Next update is already shaping up as well.Very well done! You've a flair for writing, and your research is good. This was a pleasure to read.

Chapter 97: Over the Hills

17th of October, 1905, Wednesday.

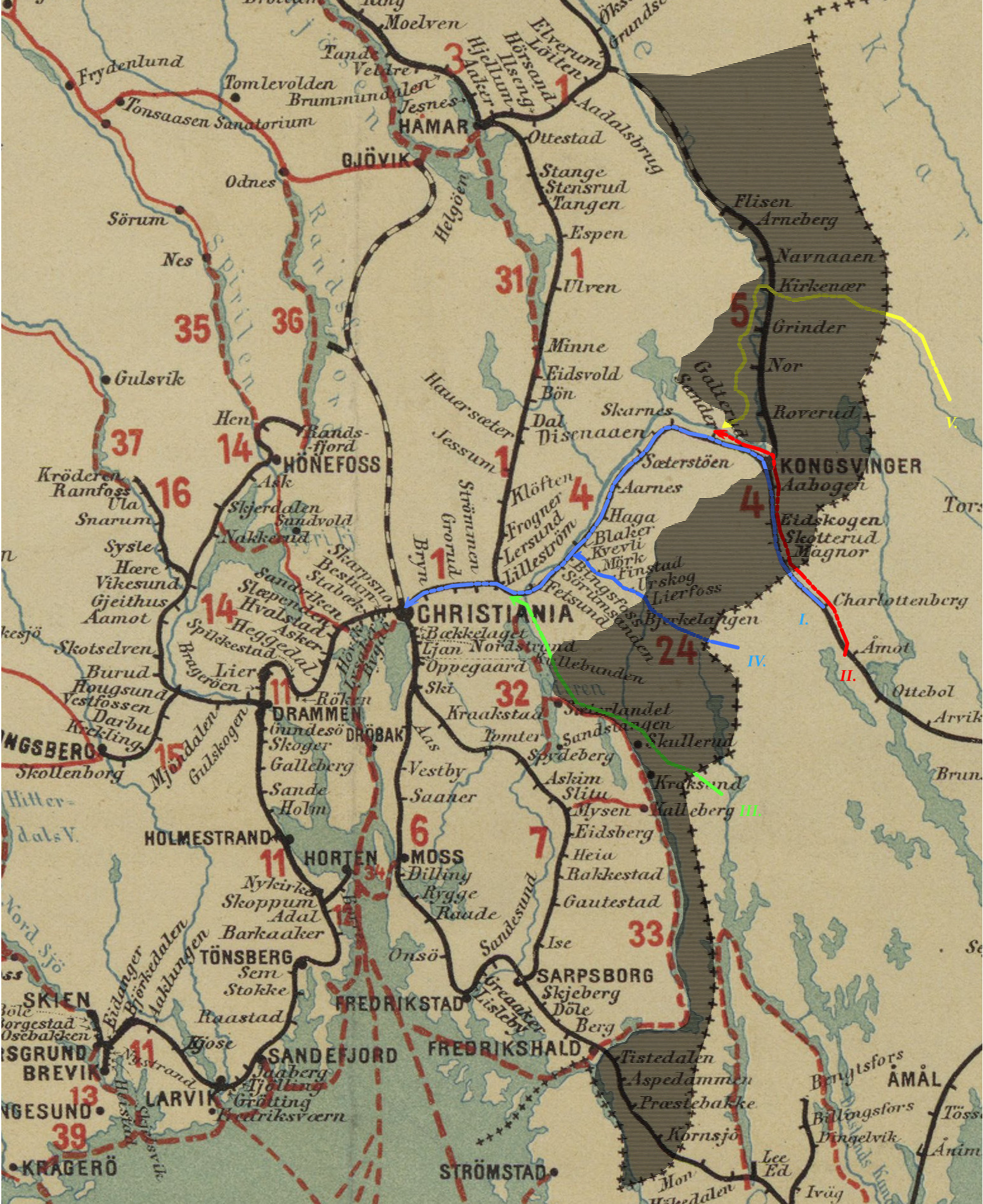

Kongsvinger, Norway.

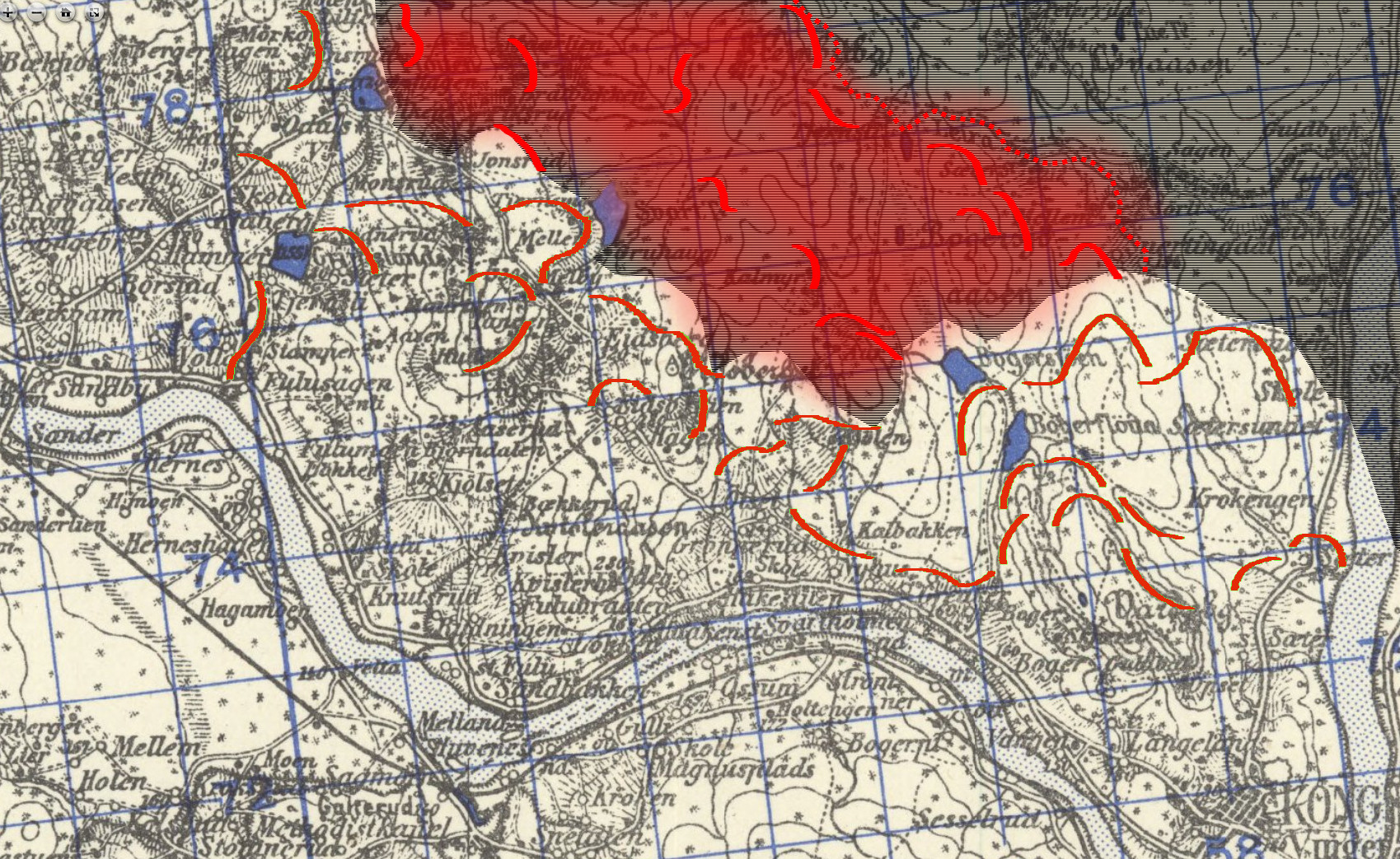

Fjärde Arméfördelningen had stopped to northern outskirts of the Norwegian lines for the last three days. Now the night was full of movement: dark figures were moving through the damp forests and hills, and oil lamps concealed beneath oilcloth illuminated the operational maps shown to the officers and NCOs. The order to attack had been given at midnight, so that the local Norwegian civilians caught in the midst of the battle would not be able to alarm their countrymen in time. The preliminary bombarment started at dawn. What had moments earlier been a beatiful vista of autumn colours on Nordic hillground now resembled an erupting volcano, as smoke and flashes of exploding shells covered the area to a thunderous barrage with a deafening rumble. Gunfire wrecked most of the breastworks, and the Norwegian defenders hunkering down on their shallow parapets were subjected to remorseless storm of steel, as shrapnel shells timed to explode over the Norwegian positions wreaked havoc among their ranks. Yet the Swedish 75mm field gun shrapnels, as horrifying as they were for infantry caught in shallow shelters, were of next to no use against the thick concrete of the stronger Norwegian fortifications.

After the Swedish artillery officers estimated that their fire had managed to suppress most of the Norwegian batteries in the sector (aside from the guns of the forts themselves), the infantry formations marched forward. General Gadd was now committing his remaining reserves, and the soldiers of the K. Lifreg. Grenadierer and K. Svea Lifgarde were now spearheading the attack that aimed to reach the northern bank of Glomma west of Kongsvinger, thus cutting the supply road to the besieged Norwegian fortress town.

The Södermanslanders and Göta Lifgarde were in reserve, since especially the latter formation had been wrecked at the fighting around Kirkenær.

As the artillery fire continued, the advancing Swedish infantry was able to approach quite close to the Norwegian positions at Eidsberg. The single skirmish line was by now the standard tactic of all Swedish infantry formations. Theoretically the forces were still following the pre-war doctrine: the skirmish line would engage the enemy, and seek to identify the location where the enemy line was perceived to be wavering or weakest. Then the main body of troops would finish the battle with a bayonet charge that was to be conducted on a two-deep wave, prererably against the flank of the enemy line. The Swedish generals in command of the campaign still by and large accepted the Prussian view that the extra momentum of closely packed troops outweighted their vulnerability. But they were already discovering that the firefight phase was consuming so much of the available infantry reserves, that it was increasingly difficult to find and rally the forces to deliver the mass shock effect that was deemed necessary for success. Hence the Swedish artillery was requested to support the assaults, ensuring that the attacking infantry could get as close as possible.

The advance was once again a grand spectacle to behold. Napoleon would have approved the sight of officers leading the attacking infantry, marching beneath regimental and national banners, with regimental bands playing rousing music. Drums and flutes led the Swedish forces onwards, towards the slopes of Eidsberg, covered in dust thrown to air by the still-continuing Swedish barrage. As the Swedish artillery fired their last rounds, the stunned, dirt-covered Norwegian defenders scrambled up from their positions. Their bleeding and ringing ears could soon pick up the menacing sound of the Swedish fältpipor and rattle of their drums. The NCOs were rushing back and forth to restore a semblance of order to the chaos of the trenches, wounded were being hastily evacuated, and the defenders were peeking from their positions to the mass of infantry that was marching towards them through the forested crest beneath the hill.

As soon as the first Swedish skirmishers got close to the barbed wire obstacles, they were immediately pinned down by bursts of mitraljøse and rifle fire. Soon the whole attacking force was incessantly exchanging fire with the Norwegians. Wounded soldiers were already wavering backwards from the firing line, supporting themselves on rifles. Others, more seriously hit, were helped back on strechers, groaning and screaming in pain and agony. The Norwegian rifle and mitraljøse fire seemed to be coming from nowhere, and felt so fierce that the Swedish attackers could hardly turn their faces towards the enemy or raise their heads.

Thus the attackers were forced to crawl up the steep hillsides, aiming and firing shots towards the direction of the muzzle flashes that were the only indication of the general direction of their foe. Crawling, aiming, firing, crawling, one meter at a time. On and on the attack proceeded. The Norwegians were dead-set to hold their ground - the Swedish attackers were equally determined to fight for their lives. Suddenly a tremendous shout arose throughout the whole Swedish line: officers, with drawn swords, pistols and blue-and-yellow regimental standards at hand, with bloodshot eyes and harsh voices, rushed towards the enemy trenches, yelling, blowing whistles and pressing and encouraging their men to follow. Foremost units pressed on, and encouraged by their example, larger forces broke upon the hill like a flood. Mass of Swedish infantry stormed to the hillside, and soon the northern hillside of Eidsberg turned into a scene from a nightmare: struggling, writhing mass of bloodsoaked figures, stabbing and shooting one another in a pitched close combat under the canopy of beatiful autumn leaves. Bayonets clashed, pistols were first shot empty and then used as bludgeons.

For one day the outnumbered Norwegians held their positions, but towards evening the Swedes, after taking heavy losses all day, managed to break through at several points. The infantry assaults on the hills north of Kongsvinger lasted three days in total. On a number of occasions the Swedes captured the Norwegian trenches, only to be driven back by desperate Norwegian counterattacks, carried through by whatever few men the Norwegians could assemble together. The next day a new Swedish assault would repeat the process. The Swedes had been able to consolidate themselves in the ditches of a few of the outer hills, and from these positions their artillery observers were able to keep the northern road to Kongsvinger under observation. Despite the fact that the initial attempt to outflank the Norwegian defenders had failed, General Gadd was adamant that the decision to doggedly (and vainly) press on had been justified, as the northern road to Kongsvinger was no longer usable during daylight hours.

Swedish government was demanding a quick conclusion of the hostilities, and the Swedish General Staff felt that attacking the Vardåsen twin forts directly could no longer wait. They knew that the Norwegian reserves were already committed - but were unaware that the western flanking manouver at the hills was by now held in place with reserves of hastily trained old men and teenager volunteers. By now the Norwegian command was like a juggler with one too many knives up in the air, desperately struggling to keep up. But as good as their spying network was, the Swedish HQ was unable to discover this fact in time. The flanking manouver was abandoned in favour of a direct assault, but that would have to wait for the Swedish siege train to arrive.

Up at the hills the war continued. Every now and then the Swedes would erect three banners: a white flag of truce, their own national standard, and the Red Cross flag. Soon men from both sides would stop firing. Then the first hesitant soldiers would stand up, soon emerging completely, watching one another from distance as medics with Red Cross armbands would rush to evacuate their wounded in tense silence. After a while the soldiers would take cover, standards would be lowered, everyone would take cover and the war would continue.

Last edited:

Good god, that's convincingly awful.

I was thinking pretty much the same. Karelian's depiction of the fighting is very well and evocatively done.

Indeed. The fine handling of macro and micro perspective is one of the great strengths of this timeline.I was thinking pretty much the same. Karelian's depiction of the fighting is very well and evocatively done.

Chapter 98: Åland Crisis

Article 1.

His Majesty the Emperor of All the Russias, in order to respond to the

wishes expressed by Their Majesties the Queen of the United Kingdom of

Great Britain and Ireland and the Emperor of the French, declares that the

Åland Islands shall not be fortified, and that no military or naval establishments whatsoever shall be maintained or created there.

For this reason, having duly examined this Convention, We have

agreed to, confirmed and ratified it, and as now We agree, confirm and ratify through Our entire reign, giving Our Imperial Word for Us,

Our inheritors and Our successors that everything stipulated in the said Convention shall be inviolably observed and executed.

In faith of which We have in Our own Hand signed this Imperial Ratification and have affixed to it the Seal of Our Empire.

Done in S:t Petersburg, on the third day of April in the Year of Grace

one thousand eight hundred and fifty-six, in the second year of Our reign.

The original is signed by His Majesty's own Hand thus:

Alexandre

Nikolay Ivanovich Bobrikov was calm and confident, as always. His eerie and impeccable presence had been unnerving for everyone who had been unfortunate enough to serve under the Baltic German aristocrat that had been called "one of the cruelest men of the Russian Army" in the foreign press. But it had impressed the Czar, who had appointed Bobrikov to act as the Governor-General of the Grand Duchy of Finland. Bobrikov had always doubted this odd little province, and the Swedish-speaking local petty bureaucrats who had clinged on their old Constitution, resisting all attempts to reform and modernize the legitimate imperial Russian authority in this corner of the Empire. Ever since he had arrived to carry out the will of the Czar, they had been whining and protesting. But Bobrikov was no fool. He had ordered arrests, banned newspapers, sacked all officials who had dared to oppose him, and used his military authority to ensure that the little region that was so vital for the economy and and everyday life of the imperial capitol remained in good order.

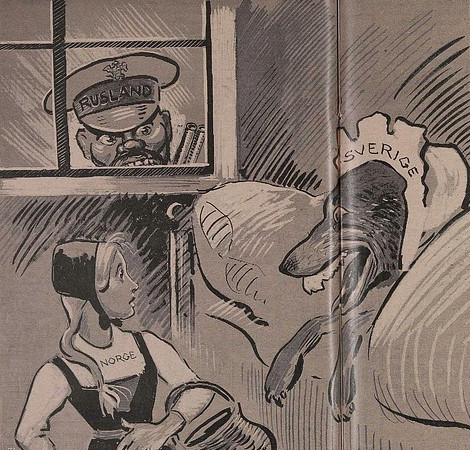

But recently he had been busy with bigger matters than pesky draft dodgers or illegal stamps. Sweden, the old and defeated foe of Russian interests in the North, was again at war. Bobrikov had made sure that the provincial garrison was in full alert, and had also been in frequent contact with Admiral Yevgeni Ivanovich Alekseyev, the newly-appointed Commander in Chief of the Russian Baltic Fleet.[1] Alekseyev was notorious figure in the capitol, always courting favours or plotting with other ambitious men that sought the Czar's favour. Sidelined by the now-defunct Triumvirate from his Far Eastern prospects, he had utilized the internal bickering among Russian Admiralty to gain himself a new prestigious position near the capitol. While Kuropatkin and Muraviev had (in vain) hoped that this would keep him too busy and out of harms way to cause any further trouble, the sudden outbreak of a new war in the North had changed everything. Alekseyev was happy, and certain that his star was once again on the rise.

Alekseyev knew that Bobrikov was a no-nonsense military man, who could not be swayed by empty promises and pretty words. For his scheme to work, Alekseyev had needed the approval of the Governor-General. But fates were certainly smiling for Admiral Alekseyev. the Grand Duchy had always been one of the main smuggling routes of censored and forbidden newspapers and literature to the rest of Russia, and even the best efforts of Bobrikov had so far failed to stop this illicit activity. But now matters were getting worse. News of mass demonstrations and riots at the streets of Stockholm were being carried to Russian Empire by smuggled newspapers, and Okhrana reports indicated that the Åland Archipelago was one of the key centers of this smuggling. It had costed Alekseyev a hefty sum, but a friendly suggestion accompanied by a fat envelope had ensured him that the report that ended up to the hands of the Governor-General painted a murky picture of the situation in the islands. But in the end exaggeration was a small sin, especially when the cause was just - at least Alekseyev himself truly believed that. And while Bobrikov loathed him and made no efforts to hide it, Alekseyev had been correct in his estimations. An official report was something that the old officer would - and could - not ignore. Thus he had managed to get Bobrikov along.

While Alekseyev was sitting by the fireplace at St. Petersburg, feeling proud of himself, the men carrying out his orders were wet and miserable.The autumn waters of the stormy Baltic were dangerous at best, but navigating them without local pilots was nearly suicidal. After the Finnish pilot service had been placed under the juristiction of the Russian Naval Ministry, the pilots had resigned en masse, and finding the ones willing and able to guide the small patrol boats towards their intented destination had delayed the scheme for weeks. It was getting dark, but the bright flashes from the lighthouse of Bokskär were visible through the rainy October night. The rest of the small flotilla would soon continue further on towards the maze of stony islands and rocks. The sleepy fishing town of Mariehamn was about to receive unexpected visitors.

1: Due the reorientation of Russian naval power from Pacific to the Baltic, this post is created half a decade earlier than in OTL.

This is a fascinating timeline. I must say that I'm not very knowledgeable about the Chinese situation, but the Swedish-Norwegian War is definitely very intriguing.

Thanks for the feedback. Work has kept me busy this autumn, but there's plenty of written material in storage. In the meantime:This is a fascinating timeline. I must say that I'm not very knowledgeable about the Chinese situation, but the Swedish-Norwegian War is definitely very intriguing.

Chapter 99: A Mahanian Gambit

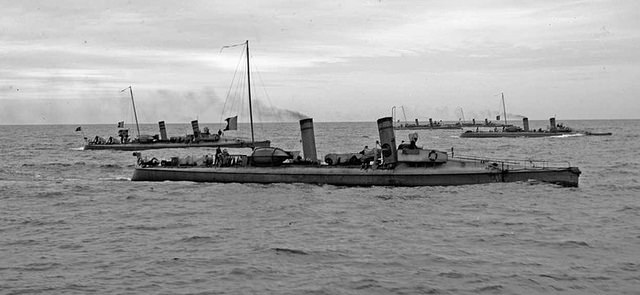

The initial locations of the combat units of the Norwegian Navy during the mobilization phase of 1905.

The Norwegian defenses of Tønsberg, Nøtterøy and Tjøme

The location of the new Norwegian naval base at Melsomvik was based on the estimation that all possible Swedish seaborne attacks would probably be aimed against the capitol, Kristiania. Consequently, the bulk of the Navy had to be concentrated nearby to protect the capitol. Melsomvik area had many natural defences. To boost them, the Norwegian planners decided early on that during mobilization naval navigation marks on mountains would be repainted, and the wooden painted seamarks relocated, so that Norwegians could still guide their own vessels, but the enemy would be unable to safely navigate the rocky waters along the mouth of the Kristianiafjord.

Despite these measures it was also deemed necessary that the new base would had to be protected by coastal artillery. Several alternatives for potential battery locations were considered, but the choice fell on Håøya in Vestfjorden, four kilometers south of Melsomvik.

1895 the rest of Håøya was bought and the year after the work began to build cannon positions on the island's south side, controlling the approaches towards Veierland, large parts of Tjøme and the route from Tønsberg to Tønne.

Håøya fort was built to open rock with two 210mm Armstrong guns, and supported by two older 150mm guns. The Armstrong canons were modern, and with the minefields in Vrengen and on both sides of Veierland, Håøya was a veritable barrier to the enemy enemy ships seeking passage north of Vestfjorden.

But the strong defense of Håøya was not enough. Since the plans for a spare harbor in Melsomvik had started to materialize from 1897, the planners noticed a need for an additional fortress on Stokkelandet, just west of Håøya. The Sundåsen area was thus purchased from local civilians, and quickly expanded. The canons placed here were a modern 12 cm caliber Krupp guns, supported by two older 150mm cannons. Sundåsen fort was completed in the year 1900. The fort was designed to support Håøya, and the two forts had a telephone connection.

After the Norwegian Coastal Artillery was established as a separate service as part of the Army, the defensive planning underwent a new change. In practice this meant that Melsomvik was still under the command of the Navy, while Sundåsen and Håøya and the naval mining forces were under the Army. Meanwhile the construction work at the new base continued, and by 1905 the Melsomvik area had new warehouses, proper quays and sheds for torpedo boats as well as new workshops.

This state of affairs was deemed entirely satisfactory for both branches of the armed forces until the disaster of the Melsomvik Incident.

As the nation was mourning the "brave martyrs of Tordenskjold", behind the scenes the generals and admirals were vitriolic and bitter, hurling open accusations of incompetence and betrayal back and forth. The mistrust and lack of communications led to severe infighting. Bearing a grudge against the Coastal Artillery, the Norwegian naval command also entered to the war badly divided. The inevitable showdown between the two competing commanders of the fleet had ultimately sidelined the cautious Vice Admiral Christian Sparre, and witnessed the rise of his aggressive Chief of Staff, Rear Admiral Jacob Børresen.

Convinced that maintaining a fleet-in-being at Kristianiafjord would doom the Norwegian fleet to defeat, Børresen had moved the remaining heavy ships of the Skagerrakeskadren further south to Kristiansand and other bases. And when the news of the impeding Swedish invasion arrived, he and his men were ready. At the cover of the darkness the ships left harbour, and soon steamed out to the open sea in combat formation. The new Telefunken radio telegraphy equipment enabled the ships of the Fleet to send messages to each other over short distances, and Børresen used this new technology to inform the other commanders about his new orders that he had purposefully kept for himself, all the while giving interviews and spreading rumours to mask his true strategy from the Swedish spies.

The older light ships units, torpedo boats and the coastal artillery would maintain high readiness, and prepare to deter all possible enemy incursions to Kristianiafjord. The Skagerrakeskadren would sail southwards, and then turn towards South-East at the northern coast of Denmark.

Børresen was personally commanding this force, and he had sailed forth with the firm intention of luring the Swedish Kustflottan out to the open sea, straight into a decisive naval battle that would settle the course of the war once and for all.

Last edited:

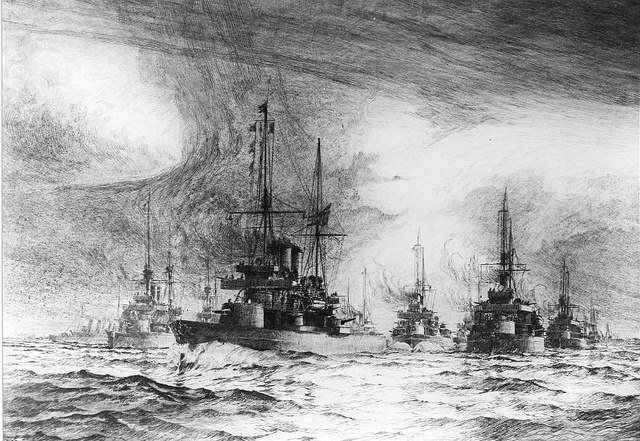

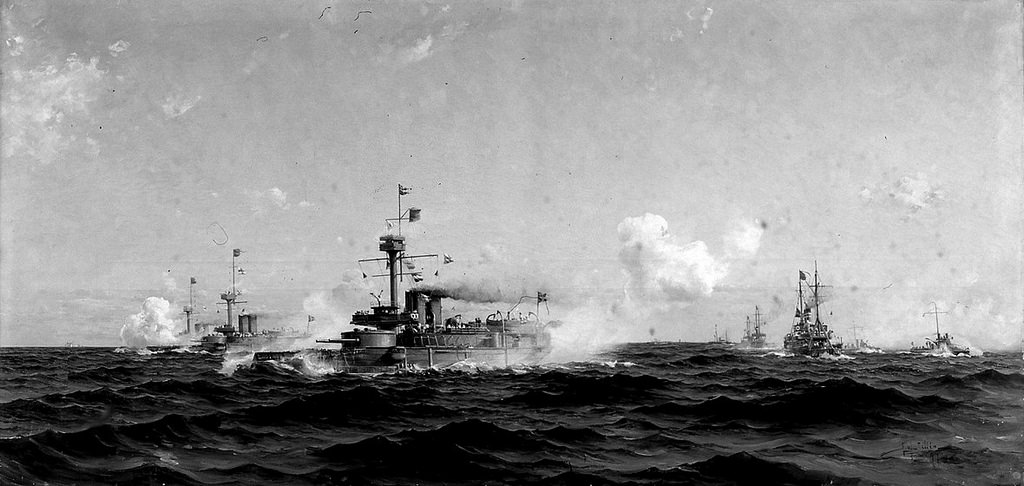

Chapter 100: Skagerrakslaget

23rd of September, 1905, Saturday.

North Sea, the Skagerrak Strait near Torbjørnskjær.

The strategic and tactical considerations that led the Swedish and Norwegian fleets to sail out in full force at the very beginning of the hostilities between the two nations were firmly rooted to the prevailing naval theories of the day.

The two opposing commanders, Rear Admiral Børresen at the helm of the Norwegian Skagerrakeskadren, as well as his Swedish opponent, Rear Admiral Wilhelm Dyrssen, the Högste Befälhavare för Kusteskadern (Highest Commander of the Coastal Squadron) and Inspektör för Flottans Övningar till Sjöss (Inspector of the Navy's Exercises at Sea) were both well-educated naval officers. Both had in fact attended to the same lectures during their training, and knew one another personally from the small social circles of the Scandinavian naval officer corps. One of the first major training decisions of Dyrssen had in fact been his order to adopt the twin column tactics that Børresen had developed for the Norwegian Navy. Both men had also advocated the procurement of new high-explosive shells to supplement the standard armor-piercing shells currently in use at the Swedish and Norwegian navies.

And now Dyrssen had little reason to ponder their similarities and shared past. He was in charge of the strongest naval force in the history of Sweden, with a task to use it to win the war against the unruly Norwegians, as quickly and effectively as possible.

Eleven armored cruisers, five modern light cruisers and 23 torpedo boats were escorting the small flotilla of transport ships - smaller coastal merchantman packed brim-full of seasick infantry, artillerymen, weapons and ammunition.

HMS Äran (HSwMS for international observers) was leading the squadron, with Tapperheten, Manligheten, Dristigheten, Oden, Thor and Niord following in column. The torpedo cruisers Örnen, Psilander, Clas Uggla, Jacob Bagge and Claes Horn formed the second column. The 24 torpedo and cannon boats escorting the flotilla struggled to keep up out in the open sea, where only the six newest vessels - Blixt, Meteor, Sterna, Orkan, Bris and Vind - were able to maintain the necessary speed to truly act as escorts.

Dyrssen was not worried. Soon the lighter vessels that were now struggling in heavier seas would once again reach the calmer waters of the Norwegian coastline, and act in their trained role a necessary close escort for the heavier armored cruisers. With their current course, the squadron would soon reach Hvaler Archipelago at the Norwegian waters.

There the escorting cannon boats would sail to the shallow archipelago, and destroy or drive away the Norwegian torpedo boats, securing the flank of the main squadron that would at the same time engage and destroy the coastal batteries at Karljohansvern. Afterwards the fleet would once again join forces, and proceed to sail westwards, cutting the Norwegian coastal railroad by naval gunfire at Holmenstarnd and Larvik. Meanwhile the numerically inferior and hopelessly outgunned Norwegian fleet would most likely hunker at their main base at Melsomvik, allowing the Swedish armada to secure the control of the seas so that the rest of the Swedish naval invasion carried out by large barges could sail forward unharassed from Stromstad.

The Army formations would then conduct a naval invasion of Tjøme on the eastern side of Nøtterøy. Large forces with seven battalions of infantry and six coastal artillery batteries with a total of 12 guns and eight howitzers would be shipped in to the new beachhead. The forces landed at Tjøme would then clear the Vrengen straight of mines, while the troops at Nøtterøy would work their way to the top of Vardås hills, and start an artillery siege of Håøya coastal fort.

This would force the Norwegian Navy to evacuate Melsomvik, but sailing out from Vestfjord they would face a superior Swedish fleet ready and waiting. Dyrssen was confident. It was a good plan, firmly Mahanian in essence. He had no doubt that in the end the Swedish sea power would carry the day.

Meanwhile Rear Admiral Børresen and the Skagerrakeskadren had not received the Swedish memorandum that assigned them to a role of a passive target. The Norwegians were also out at sea, sailing towards southeast and Gothenburg with full steam. Børresen was leading his flotilla from the Norwegian flagship, the armored cruiser Eidsvold, followed by the two other Norwegian Panserskips, Norge and Harald Haarfagre, escorted by 20 more or less seaworthy Norwegian 1st- and second-class torpedo boats.

Børresen was following his training and instincts. He had from the start wanted to move his small battlefleet out to the open sea, as he felt that the only way he could effectively engage the Swedish fleet would be by by bringing the firepower of his whole force into battle effectively against a portion of the Swedish fleet. This way he could at least hope to gain local and temporary fire superiority that he hoped to utilize to defeat the Swedish warships in detail. Børresen knew that he was commanding a force that was both outnumbered and outgunned, and felt that this approach was a tactical necessity for him.

But massing forces in the face of an enemy that could see his every move was tricky. Hence he had opted to abandon the Melsomvik base and move out in the darkness of the night. Retreating to the bases further west and playing fleet-in-being against the Swedes was an option he had not even contemplated seriously. Despite the desperate strategic situation Børresen preferred to see his plan as an opportunity to exploit, rather than a glory-seeking and outright suicidal throw of the dice.

Børresen had done everything in his power to prepare his forces. He had spent the last three months training this little armada, and had stressed on artillery drills where the armored cruisers would open fire from extremely long distance: 7 000, 8 000, maybe even 9 000 meters. He knew that from this maximum range only the most heavy-caliber guns of either fleet would be within range - and he preferred to keep it that way.

Firmly aware of the capacities of the Swedish ships, he knew that starting from 8 000 meters, the Swedish medium-caliber guns would also quickly become effective, especially against personnel and unarmored parts of his ships. If the Swedes could close the distance even more, to five kilometers, the Norwegians would be in dire trouble. At that range the Swedish 15cm guns would be able to fire faster than the heavier Norwegian 21 cm guns, and despite the fact that the 21mm shells had more impact energy than the smaller-caliber medium guns, the Swedish guns would be able to deliver more shells and firepower against the Norwegians as the distance grew closer.

If Børresen could not exploit the better speed of his ships, then the greater armor penetration values and longer accurate range of the Norwegian guns would mean very little. The Swedish torpedoes would become a hazard as well if the distance shrunk to a mere few kilometers. Not that it mattered: the Swedish fleet would by then have been able to pulverize the Norwegian ships with small- and medium-caliber gunfire long before they were in torpedo range.

The cold, hard mathematical calculations the Admiral was so fond of seemed to spell doom for his ships and their crews. Børresen knew his facts and figures very well, and now the tedious, ever so dull voice of the old lecturer from the ballistics course echoed in his mind as an ill omen and haunted him: "To compensate for a firepower inferiority of 50 percent, the effective number of hits must be reduced by 75 percent..."

And his small fleet was even more outgunned than that. Thus he had to avoid being hit. Easy, wasn’t it? Keeping the formation in control and focused on the task at hand was critical for success. Børresen shared the opinion of other naval theorists of the day. The days of Nelson were history. The fleets had to tactically outplay their foes by keeping their own formations intact and disturbing the enemy attempts of concentrated action.

The cruising formation he had adopted to solve this tactical dilemma was two short columns, abreast of one another. This allowed him to quickly order the fleet to move to a single line with close intervals. But while the tactical invention of Børresen looked simple on paper, it had taken years of training to turn it into a feasible tactical feat. He had yelled and cursed as well as appraised, rewarded and promoted with equal vigor, pushing through countless close-order gunnery and cruising drills.

Yes, he could not blame himself for not doing more. If only those blasted fools of the Coastal Artillery - the Army! - had not destroyed 25% of his battlefleet with a single displaced naval mine! At full strength, fully drilled and combat-ready, the Skagerrakeskadern would have been a powerful protector of Norwegian sovereignty.

Now it was a wounded beast - still a spectacle to behold, but not terrible enough to keep the Swedes at bay. Thus he had to do the same as his great idol. The great Tordenskiold had never shunned combat, no matter the odds - and neither would he!

It was a gray, chilly September morning, with misty and rainy weather conditions at dawn. Despite the difficult conditions the Norwegian spotters noticed steam from the horizon on 06:07. While Skagerrak was full of merchant shipping and they had already had a few false alarms with Danish fishing boats earlier that night, within minutes the number of reported visual contacts grew rapidly.

Sweden was sailing for war.

Børresen made a quick decision to keep the course of his main squadron southwards, signalling the torpedo boats an order to maintain the distance and course at the eastern flank of the combat formation.

The three Norwegian capital ships were able to close in as the rising sun began to dissipate the mist, and the cloud cover begun to break. The Swedish ships became clearly visible next to the rising dawn at the eastern sky. The Swedish spotters noticed the approaching Norwegians from 11km distance. There was a short confusion on the Swedish side, as the Norwegians were approaching from west, rather than north along the coast. Not wanting to start an international incident with Germany or Britain by accident, Dyrssen signaled the Swedish armored cruiser line to chance course towards the foe to positively identify the unknown contact before further orders.

By now Eidsvold was within 9 000 meters, and opened fire, as Børresen altered his course slightly to maintain the distance from the Swedish ships.

The Swedish initial tactical position was difficult. Dyrssen knew that the Norwegian vessels were better than most of his capital ships, and that the Swedish strengths rested on maintaining unity of movement and massive firepower. Unfortunately that would have jeopardized the critically timetabled and carefully prepared mission. The Army was counting on the Navy to keep on schedule with the invasion plan, and Dyrssen knew that any delays here could have disastrous results later on.

The Swedish admiral wanted to make his numbers count, and sought to keep the numerically inferior Norwegians at bay while deploying the whole fleet to meet the foe.

But this was all just a quickly improvised new plan at his head when the Kusteskadern first returned fire. The leading armored cruisers - Tapperheten, Manligheten and Dristigheten - fired the first shots in anger from their forward turrets, turning towards the Norwegians and screening the rest of the fleet that now begun a series of manoeuvres to reorient themselves to an advantageous tactical position.

Dyrssen had divided his own force to smaller tactical groups, that now begun to operate with predetermined and -drilled orders. The cruisers Oden and Niord, with the support of 1st-class torpedo boats Orkan and Komet, continued towards northwest, seeking to cut the shortest escape route of the Norwegians. Dyrssen was still amazed that the Norwegians had dared to venture this far to the open sea, and now wanted to keep them away from Melsomvik at all costs.

Svea and Thule, supported by gunboats Urd, Disa and Hugin, continued northwards along the original sailing course, forming the middle column supporting the Swedish torpedo boats and destroyers.

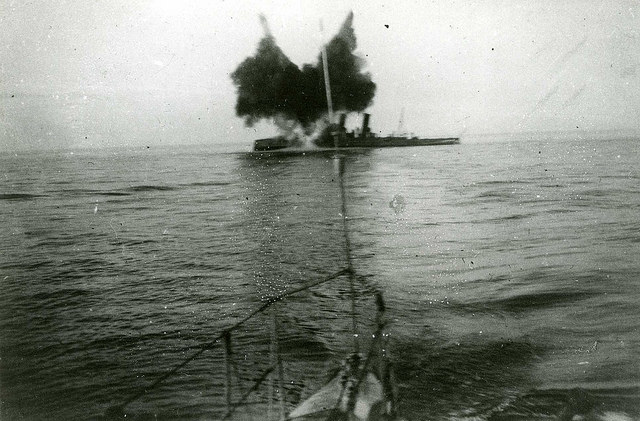

And the five Swedish torpedo cruisers boldly dashed forward on their own initiative, turning south with a direct intercept course towards the Norwegian fleet. Closing in with their faster engines, they quickly drew the concentrated fire of the Norwegian ships. The first salvo of a total of twelve heavy guns - six Norwegian and six Swedish, had witnessed a single scraping AP shell hit to the rear deck of HSwMS Tapperheten, but the ship had braved the near-miss well.

As the torpedo cruisers now tried to close the distance, they came in range of the quick-firing medium caliber guns of the Norwegian fleet. The leading ship, HSwMS Psilander, was suddenly engulfed in a huge blast of smoke and fire, as plunging HE shell detonated below her front deck with disastrous results.

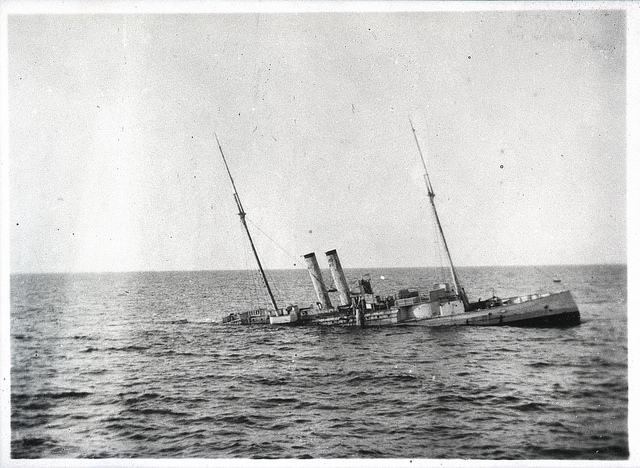

The battle was less than fifteen minutes old when the first ship was already quickly sinking to the depths of Skagerrak. The gunfire from both sides only escalated, as the Norwegians were encouraged from their success and Swedes sought to avenge their loss, as the rest of their torpedo cruisers disengaged. For the rest of the battle, the armored cruisers of both sides continued their long-range gun duel, with Swedes turning to cruise on a parallel line with the Norwegians. At the same time the northern flank of the battle witnessed entirely different kind of fighting.

The Norwegian torpedo boats attacked against Oden and Niord. The fastest and most seaworthy 1st-class Norwegian torpedo boats - Sæl, Skrei, Brand, Storm and Sild - rushed forward, five small ships side by side. Their crewmen knew that closing the distance to a naval knife-fight was a necessity for their survival - achieving a high chance to hit with their torpedoes would paradoxically be their only chance to escape the murderous fire of the Swedish small-calibre weapons.

The Swedish Orkan and Komet quickly signalled support from the rest of the Swedish torpedo- and cannon boat flotilla, and surged forward to meet the Norwegian charge.

The following close-range fighting rapidly mounted casualties of the battle, as the two 37mm Hotchkiss deck cannons that each of the Norwegian torpedo boats carried started to lob small HE shells, and the 47mm M/95 deck guns of the Swedish cannon boats returned fire. The smaller ships twisted and turned, firing furiously as they sought to get closer to one another while avoiding the small shells that would rip their hulls apart.

Part of the Swedish torpedo boat flotilla was already engaged in combat further south. The first true destroyers of the Swedish fleet, the British-built HMS Mode and HMS Magne, were leading the smaller torpedo boats ahead, only to be harassed away by the determined fire of the smaller guns of the Norwegian ships. By now Børresen knew that his initial mission had failed. The Norwegian ships had already taken several hits, and keeping the distance at maximum possible range had enabled him to trade fire with the best Swedish ships from afar. Unknown to Børresen, the captain of Harald Haarfagre had by now grown frustrated to the lack of punch of the Norwegian AP shells, and issued orders to switch to HE shells. Firing against Dristigheten, the Norwegian warship managed to severely cripple the Swedish cruiser with a well-aimed double hit that damaged and outright destroyed several smaller light side turrets, and wounded the captain of the Swedish armored cruiser. Meanwhile both sides had already taken several non-critical hits. Norge was no longer able to effectively return fire. Her twin main turret was jammed by a Swedish shell. More and more shells were landing closer and closer of the Norwegian battle line, as Swedish medium-caliber guns were already firing, despite still being away from their effective range.

And so Børresen turned westwards, towards the open seas, and away from the coast, as the few escorting Norwegian torpedo boats broke up a wall of smoke to cover the turn. The rest of the Norwegian torpedo boats had earlier on aborted their torpedo attack, and also broken contact at the cover of smoke after the Swedish cannon boats had began to amass against them.

Before that Hval and Laks had been lost to Swedish gunfire, and Ørn and Teist that had been able to limp away from the fight were soon scuttled at Hvaler islands, after their engines malfunctioned due extensive combat damage.

By afternoon Børresen listened the radio reports from the torpedo boat flotilla from Hvaler with relief. Getting the majority of his light units back to position to contest the Swedish approach to the Kristianiafjord had been a pivotal part of his plan. He had originally expected to catch the Swedish fleet still napping at the narrow archipelago near Strömstad, and meeting them almost head-on at the open seas had not been his preferred tactical situation.

But his ships had survived, beaten and bruised, but still battleworthy. Sinking the Swedish torpedo cruiser with a single hit had been a glorious sight, and was certain to raise the morale of the small Norwegian fleet. The Swedish fleet had tried to do everything at once, failing to concentrate their firepower against his small fleet until he was already disengaging and breaking contact. And unwilling to leave their older ships behind, the Swedes had opted not to pursue with full force. The arrogant fools. Now it was time to sail to Kristiansand for a short rest and refit. Then they would sortie again.

Meanwhile the Swedish fleet sailed back home to break the news of the initial naval engagement to the Admiralty. Dyrssen was not too worried. After all, weren't all plans just decorative maps and grand dreams waiting to be crushed by the grim reality of war? The Norwegians had tried to stop them with everything they had, and he had soundly beaten them back, damaging all of their capital ships and seizing the control of the seas.

The grand operation would have to be postponed for a few days, but all the critical pieces of this chess game for the future of Norway were still on table. Soon they would play again. And he would win, maybe not tomorrow but soon enough in any case. The Norwegians would have to be lucky every time, while the Swedes only needed a few good hits to win a decisive victory.

As the exhausted Norwegian crews carefully piloted their way towards the naval base at Kristiansand after sunset in the pitch-black Nordic autumn darkness, no one noticed a small metal turret that peaked from the water along the route of the Norwegian fleet. The ten men inside the half-submerged vessel were miserable, wet and chilled to the bone despite being clad in furs to keep themselves warm in the freezing metal coffin that had slowly made its way through the sea for most of the day. Their small ship smelled of leaking battery acid, kerosene fumes, vomit and piss. Yet the men were now forgetting all that. They were at their battle stations, closely following the commands that their captain was almost whispering with a silent voice from the bridge of the small craft. Just a few hundred meters more, and the first approaching Norwegian ship would be in range of the sole torpedo tube of the Swedish submarine.

North Sea, the Skagerrak Strait near Torbjørnskjær.

The strategic and tactical considerations that led the Swedish and Norwegian fleets to sail out in full force at the very beginning of the hostilities between the two nations were firmly rooted to the prevailing naval theories of the day.

The two opposing commanders, Rear Admiral Børresen at the helm of the Norwegian Skagerrakeskadren, as well as his Swedish opponent, Rear Admiral Wilhelm Dyrssen, the Högste Befälhavare för Kusteskadern (Highest Commander of the Coastal Squadron) and Inspektör för Flottans Övningar till Sjöss (Inspector of the Navy's Exercises at Sea) were both well-educated naval officers. Both had in fact attended to the same lectures during their training, and knew one another personally from the small social circles of the Scandinavian naval officer corps. One of the first major training decisions of Dyrssen had in fact been his order to adopt the twin column tactics that Børresen had developed for the Norwegian Navy. Both men had also advocated the procurement of new high-explosive shells to supplement the standard armor-piercing shells currently in use at the Swedish and Norwegian navies.

And now Dyrssen had little reason to ponder their similarities and shared past. He was in charge of the strongest naval force in the history of Sweden, with a task to use it to win the war against the unruly Norwegians, as quickly and effectively as possible.

Eleven armored cruisers, five modern light cruisers and 23 torpedo boats were escorting the small flotilla of transport ships - smaller coastal merchantman packed brim-full of seasick infantry, artillerymen, weapons and ammunition.

HMS Äran (HSwMS for international observers) was leading the squadron, with Tapperheten, Manligheten, Dristigheten, Oden, Thor and Niord following in column. The torpedo cruisers Örnen, Psilander, Clas Uggla, Jacob Bagge and Claes Horn formed the second column. The 24 torpedo and cannon boats escorting the flotilla struggled to keep up out in the open sea, where only the six newest vessels - Blixt, Meteor, Sterna, Orkan, Bris and Vind - were able to maintain the necessary speed to truly act as escorts.

Dyrssen was not worried. Soon the lighter vessels that were now struggling in heavier seas would once again reach the calmer waters of the Norwegian coastline, and act in their trained role a necessary close escort for the heavier armored cruisers. With their current course, the squadron would soon reach Hvaler Archipelago at the Norwegian waters.

There the escorting cannon boats would sail to the shallow archipelago, and destroy or drive away the Norwegian torpedo boats, securing the flank of the main squadron that would at the same time engage and destroy the coastal batteries at Karljohansvern. Afterwards the fleet would once again join forces, and proceed to sail westwards, cutting the Norwegian coastal railroad by naval gunfire at Holmenstarnd and Larvik. Meanwhile the numerically inferior and hopelessly outgunned Norwegian fleet would most likely hunker at their main base at Melsomvik, allowing the Swedish armada to secure the control of the seas so that the rest of the Swedish naval invasion carried out by large barges could sail forward unharassed from Stromstad.

The Army formations would then conduct a naval invasion of Tjøme on the eastern side of Nøtterøy. Large forces with seven battalions of infantry and six coastal artillery batteries with a total of 12 guns and eight howitzers would be shipped in to the new beachhead. The forces landed at Tjøme would then clear the Vrengen straight of mines, while the troops at Nøtterøy would work their way to the top of Vardås hills, and start an artillery siege of Håøya coastal fort.

This would force the Norwegian Navy to evacuate Melsomvik, but sailing out from Vestfjord they would face a superior Swedish fleet ready and waiting. Dyrssen was confident. It was a good plan, firmly Mahanian in essence. He had no doubt that in the end the Swedish sea power would carry the day.

Meanwhile Rear Admiral Børresen and the Skagerrakeskadren had not received the Swedish memorandum that assigned them to a role of a passive target. The Norwegians were also out at sea, sailing towards southeast and Gothenburg with full steam. Børresen was leading his flotilla from the Norwegian flagship, the armored cruiser Eidsvold, followed by the two other Norwegian Panserskips, Norge and Harald Haarfagre, escorted by 20 more or less seaworthy Norwegian 1st- and second-class torpedo boats.

Børresen was following his training and instincts. He had from the start wanted to move his small battlefleet out to the open sea, as he felt that the only way he could effectively engage the Swedish fleet would be by by bringing the firepower of his whole force into battle effectively against a portion of the Swedish fleet. This way he could at least hope to gain local and temporary fire superiority that he hoped to utilize to defeat the Swedish warships in detail. Børresen knew that he was commanding a force that was both outnumbered and outgunned, and felt that this approach was a tactical necessity for him.

But massing forces in the face of an enemy that could see his every move was tricky. Hence he had opted to abandon the Melsomvik base and move out in the darkness of the night. Retreating to the bases further west and playing fleet-in-being against the Swedes was an option he had not even contemplated seriously. Despite the desperate strategic situation Børresen preferred to see his plan as an opportunity to exploit, rather than a glory-seeking and outright suicidal throw of the dice.

Børresen had done everything in his power to prepare his forces. He had spent the last three months training this little armada, and had stressed on artillery drills where the armored cruisers would open fire from extremely long distance: 7 000, 8 000, maybe even 9 000 meters. He knew that from this maximum range only the most heavy-caliber guns of either fleet would be within range - and he preferred to keep it that way.

Firmly aware of the capacities of the Swedish ships, he knew that starting from 8 000 meters, the Swedish medium-caliber guns would also quickly become effective, especially against personnel and unarmored parts of his ships. If the Swedes could close the distance even more, to five kilometers, the Norwegians would be in dire trouble. At that range the Swedish 15cm guns would be able to fire faster than the heavier Norwegian 21 cm guns, and despite the fact that the 21mm shells had more impact energy than the smaller-caliber medium guns, the Swedish guns would be able to deliver more shells and firepower against the Norwegians as the distance grew closer.

If Børresen could not exploit the better speed of his ships, then the greater armor penetration values and longer accurate range of the Norwegian guns would mean very little. The Swedish torpedoes would become a hazard as well if the distance shrunk to a mere few kilometers. Not that it mattered: the Swedish fleet would by then have been able to pulverize the Norwegian ships with small- and medium-caliber gunfire long before they were in torpedo range.

The cold, hard mathematical calculations the Admiral was so fond of seemed to spell doom for his ships and their crews. Børresen knew his facts and figures very well, and now the tedious, ever so dull voice of the old lecturer from the ballistics course echoed in his mind as an ill omen and haunted him: "To compensate for a firepower inferiority of 50 percent, the effective number of hits must be reduced by 75 percent..."

And his small fleet was even more outgunned than that. Thus he had to avoid being hit. Easy, wasn’t it? Keeping the formation in control and focused on the task at hand was critical for success. Børresen shared the opinion of other naval theorists of the day. The days of Nelson were history. The fleets had to tactically outplay their foes by keeping their own formations intact and disturbing the enemy attempts of concentrated action.

The cruising formation he had adopted to solve this tactical dilemma was two short columns, abreast of one another. This allowed him to quickly order the fleet to move to a single line with close intervals. But while the tactical invention of Børresen looked simple on paper, it had taken years of training to turn it into a feasible tactical feat. He had yelled and cursed as well as appraised, rewarded and promoted with equal vigor, pushing through countless close-order gunnery and cruising drills.

Yes, he could not blame himself for not doing more. If only those blasted fools of the Coastal Artillery - the Army! - had not destroyed 25% of his battlefleet with a single displaced naval mine! At full strength, fully drilled and combat-ready, the Skagerrakeskadern would have been a powerful protector of Norwegian sovereignty.

Now it was a wounded beast - still a spectacle to behold, but not terrible enough to keep the Swedes at bay. Thus he had to do the same as his great idol. The great Tordenskiold had never shunned combat, no matter the odds - and neither would he!

It was a gray, chilly September morning, with misty and rainy weather conditions at dawn. Despite the difficult conditions the Norwegian spotters noticed steam from the horizon on 06:07. While Skagerrak was full of merchant shipping and they had already had a few false alarms with Danish fishing boats earlier that night, within minutes the number of reported visual contacts grew rapidly.

Sweden was sailing for war.

Børresen made a quick decision to keep the course of his main squadron southwards, signalling the torpedo boats an order to maintain the distance and course at the eastern flank of the combat formation.

The three Norwegian capital ships were able to close in as the rising sun began to dissipate the mist, and the cloud cover begun to break. The Swedish ships became clearly visible next to the rising dawn at the eastern sky. The Swedish spotters noticed the approaching Norwegians from 11km distance. There was a short confusion on the Swedish side, as the Norwegians were approaching from west, rather than north along the coast. Not wanting to start an international incident with Germany or Britain by accident, Dyrssen signaled the Swedish armored cruiser line to chance course towards the foe to positively identify the unknown contact before further orders.

By now Eidsvold was within 9 000 meters, and opened fire, as Børresen altered his course slightly to maintain the distance from the Swedish ships.

The Swedish initial tactical position was difficult. Dyrssen knew that the Norwegian vessels were better than most of his capital ships, and that the Swedish strengths rested on maintaining unity of movement and massive firepower. Unfortunately that would have jeopardized the critically timetabled and carefully prepared mission. The Army was counting on the Navy to keep on schedule with the invasion plan, and Dyrssen knew that any delays here could have disastrous results later on.

The Swedish admiral wanted to make his numbers count, and sought to keep the numerically inferior Norwegians at bay while deploying the whole fleet to meet the foe.

But this was all just a quickly improvised new plan at his head when the Kusteskadern first returned fire. The leading armored cruisers - Tapperheten, Manligheten and Dristigheten - fired the first shots in anger from their forward turrets, turning towards the Norwegians and screening the rest of the fleet that now begun a series of manoeuvres to reorient themselves to an advantageous tactical position.

Dyrssen had divided his own force to smaller tactical groups, that now begun to operate with predetermined and -drilled orders. The cruisers Oden and Niord, with the support of 1st-class torpedo boats Orkan and Komet, continued towards northwest, seeking to cut the shortest escape route of the Norwegians. Dyrssen was still amazed that the Norwegians had dared to venture this far to the open sea, and now wanted to keep them away from Melsomvik at all costs.

Svea and Thule, supported by gunboats Urd, Disa and Hugin, continued northwards along the original sailing course, forming the middle column supporting the Swedish torpedo boats and destroyers.

And the five Swedish torpedo cruisers boldly dashed forward on their own initiative, turning south with a direct intercept course towards the Norwegian fleet. Closing in with their faster engines, they quickly drew the concentrated fire of the Norwegian ships. The first salvo of a total of twelve heavy guns - six Norwegian and six Swedish, had witnessed a single scraping AP shell hit to the rear deck of HSwMS Tapperheten, but the ship had braved the near-miss well.

As the torpedo cruisers now tried to close the distance, they came in range of the quick-firing medium caliber guns of the Norwegian fleet. The leading ship, HSwMS Psilander, was suddenly engulfed in a huge blast of smoke and fire, as plunging HE shell detonated below her front deck with disastrous results.

The battle was less than fifteen minutes old when the first ship was already quickly sinking to the depths of Skagerrak. The gunfire from both sides only escalated, as the Norwegians were encouraged from their success and Swedes sought to avenge their loss, as the rest of their torpedo cruisers disengaged. For the rest of the battle, the armored cruisers of both sides continued their long-range gun duel, with Swedes turning to cruise on a parallel line with the Norwegians. At the same time the northern flank of the battle witnessed entirely different kind of fighting.

The Norwegian torpedo boats attacked against Oden and Niord. The fastest and most seaworthy 1st-class Norwegian torpedo boats - Sæl, Skrei, Brand, Storm and Sild - rushed forward, five small ships side by side. Their crewmen knew that closing the distance to a naval knife-fight was a necessity for their survival - achieving a high chance to hit with their torpedoes would paradoxically be their only chance to escape the murderous fire of the Swedish small-calibre weapons.

The Swedish Orkan and Komet quickly signalled support from the rest of the Swedish torpedo- and cannon boat flotilla, and surged forward to meet the Norwegian charge.

The following close-range fighting rapidly mounted casualties of the battle, as the two 37mm Hotchkiss deck cannons that each of the Norwegian torpedo boats carried started to lob small HE shells, and the 47mm M/95 deck guns of the Swedish cannon boats returned fire. The smaller ships twisted and turned, firing furiously as they sought to get closer to one another while avoiding the small shells that would rip their hulls apart.

Part of the Swedish torpedo boat flotilla was already engaged in combat further south. The first true destroyers of the Swedish fleet, the British-built HMS Mode and HMS Magne, were leading the smaller torpedo boats ahead, only to be harassed away by the determined fire of the smaller guns of the Norwegian ships. By now Børresen knew that his initial mission had failed. The Norwegian ships had already taken several hits, and keeping the distance at maximum possible range had enabled him to trade fire with the best Swedish ships from afar. Unknown to Børresen, the captain of Harald Haarfagre had by now grown frustrated to the lack of punch of the Norwegian AP shells, and issued orders to switch to HE shells. Firing against Dristigheten, the Norwegian warship managed to severely cripple the Swedish cruiser with a well-aimed double hit that damaged and outright destroyed several smaller light side turrets, and wounded the captain of the Swedish armored cruiser. Meanwhile both sides had already taken several non-critical hits. Norge was no longer able to effectively return fire. Her twin main turret was jammed by a Swedish shell. More and more shells were landing closer and closer of the Norwegian battle line, as Swedish medium-caliber guns were already firing, despite still being away from their effective range.

And so Børresen turned westwards, towards the open seas, and away from the coast, as the few escorting Norwegian torpedo boats broke up a wall of smoke to cover the turn. The rest of the Norwegian torpedo boats had earlier on aborted their torpedo attack, and also broken contact at the cover of smoke after the Swedish cannon boats had began to amass against them.

Before that Hval and Laks had been lost to Swedish gunfire, and Ørn and Teist that had been able to limp away from the fight were soon scuttled at Hvaler islands, after their engines malfunctioned due extensive combat damage.

By afternoon Børresen listened the radio reports from the torpedo boat flotilla from Hvaler with relief. Getting the majority of his light units back to position to contest the Swedish approach to the Kristianiafjord had been a pivotal part of his plan. He had originally expected to catch the Swedish fleet still napping at the narrow archipelago near Strömstad, and meeting them almost head-on at the open seas had not been his preferred tactical situation.

But his ships had survived, beaten and bruised, but still battleworthy. Sinking the Swedish torpedo cruiser with a single hit had been a glorious sight, and was certain to raise the morale of the small Norwegian fleet. The Swedish fleet had tried to do everything at once, failing to concentrate their firepower against his small fleet until he was already disengaging and breaking contact. And unwilling to leave their older ships behind, the Swedes had opted not to pursue with full force. The arrogant fools. Now it was time to sail to Kristiansand for a short rest and refit. Then they would sortie again.

Meanwhile the Swedish fleet sailed back home to break the news of the initial naval engagement to the Admiralty. Dyrssen was not too worried. After all, weren't all plans just decorative maps and grand dreams waiting to be crushed by the grim reality of war? The Norwegians had tried to stop them with everything they had, and he had soundly beaten them back, damaging all of their capital ships and seizing the control of the seas.

The grand operation would have to be postponed for a few days, but all the critical pieces of this chess game for the future of Norway were still on table. Soon they would play again. And he would win, maybe not tomorrow but soon enough in any case. The Norwegians would have to be lucky every time, while the Swedes only needed a few good hits to win a decisive victory.

As the exhausted Norwegian crews carefully piloted their way towards the naval base at Kristiansand after sunset in the pitch-black Nordic autumn darkness, no one noticed a small metal turret that peaked from the water along the route of the Norwegian fleet. The ten men inside the half-submerged vessel were miserable, wet and chilled to the bone despite being clad in furs to keep themselves warm in the freezing metal coffin that had slowly made its way through the sea for most of the day. Their small ship smelled of leaking battery acid, kerosene fumes, vomit and piss. Yet the men were now forgetting all that. They were at their battle stations, closely following the commands that their captain was almost whispering with a silent voice from the bridge of the small craft. Just a few hundred meters more, and the first approaching Norwegian ship would be in range of the sole torpedo tube of the Swedish submarine.

Last edited:

The Norwegian and Swedish digital museums are really good resources. As a result all the ships mentioned in the story are also correctly featured in the illustrations and photographs.Nicely done! The inclusion of the drawings and photographs was a treat, thanks for adding them!

High quality work as always, Karelian. There are currently no other TLs quite like this being written, in terms of great content and Nordic (and Russian) history both and what you are doing here is a rare treat.

As for your comment, digital museums and archives are one of the great things of our era, both for "serious research" and other nifty uses. Happily the Nordic countries have invested some effort on that front.

As for your comment, digital museums and archives are one of the great things of our era, both for "serious research" and other nifty uses. Happily the Nordic countries have invested some effort on that front.

I am surprised that the submarine is waiting anywhere near there when the Swedes were sure that the fleet was in Melsomvik?

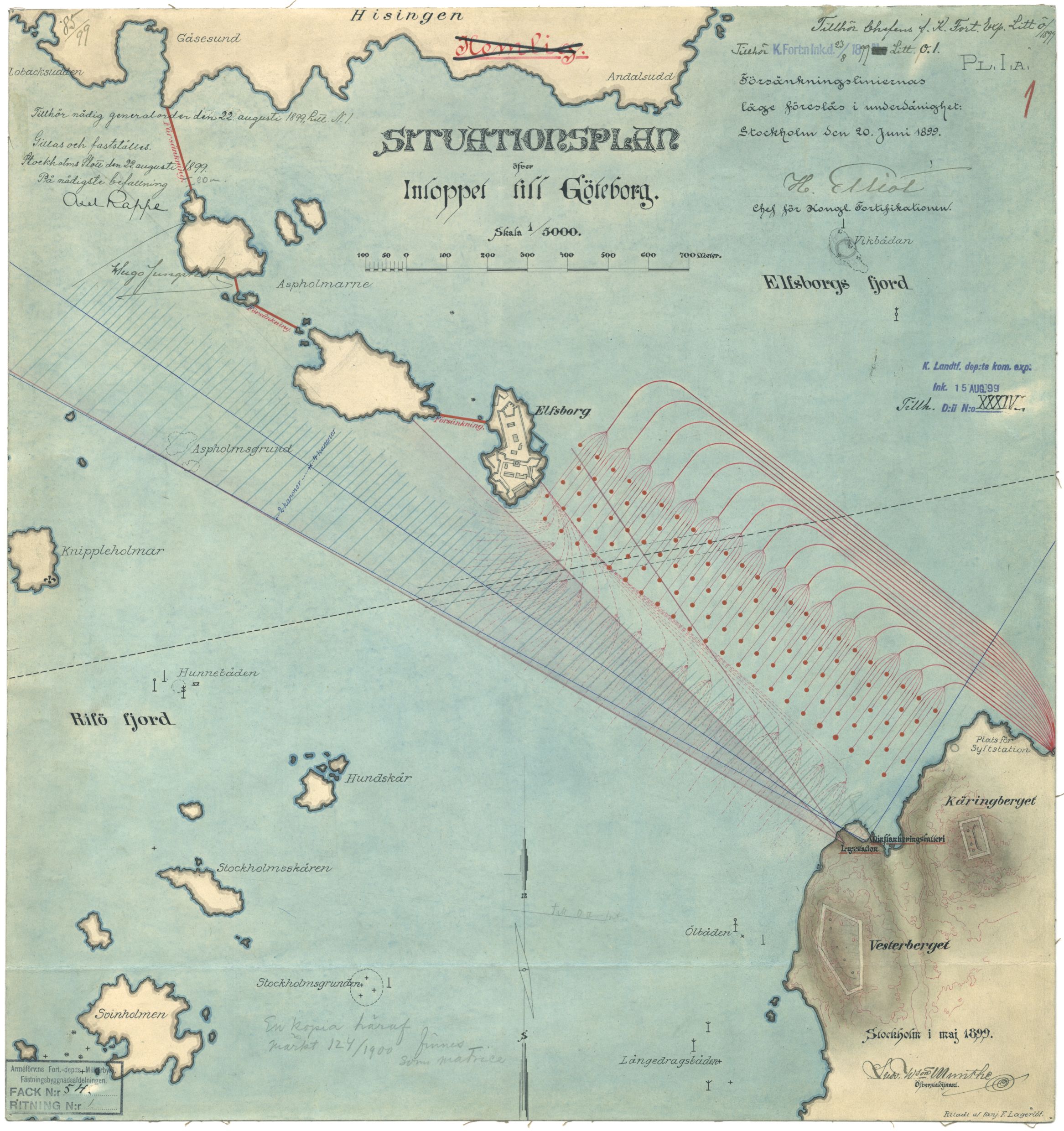

Good point. Melsomvik, however, has much more narrow approaches that are known to be mined: https://www.google.fi/maps/place/31...71f345dbf8178a3!8m2!3d59.2143701!4d10.3356955

Whereas Kristiansand has a busy harbour, and the actual naval base near the city (Marvika orlogsstasjon) is located further inland: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1IN7mdysGg2IFVWtoMHRd2jOjy5U&hl=en&ll=58.34010218220455,8.093116499999951&z=10 - Marvika is south-east of the southern harbour. And most importantly, this base has only one entry and exit point - which was the historical reason the Norwegians abandoned it in favour of Melsomvik.

Captain Magnusson and his small crew are operating an entirely new kind of vessel, and the Swedish Admiralty has been uncertain on how to use it most efficiently. It was too slow to effectively follow the main fleet, and lacked guns to support the invasion. Sneaking up beforehand to ambush the closest and most likely escape destination of the possible survivors of the Norwegian fleet therefore made perfect sense in the pre-war Swedish plan: http://borreminne.hive.no/aargangene/2004/Bilder/117kartmedtekst.jpg

Augustendal Avance paraffin oil motor gave the Hajen a maximum operational range of 640 NM.

The direct distance between Strömstad and Kristiansand is 116 NM, and with a maximum speed of 9 knots, the boat could reach it in 13 hours.

Now, the fun part of it all is the fact that the ship lacks any kind of wireless connections to the outside world. Hence it has been dispatched on the previous evening, with orders to observe the military activity of Marvika naval base, attack possible targets of opportunity - especially Norwegian warships arriving to the base later at night - and return back to Strömstad for rest and refit afterwards.

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Share: