The Macedonian Crisis, part IV: Byzantine Politics

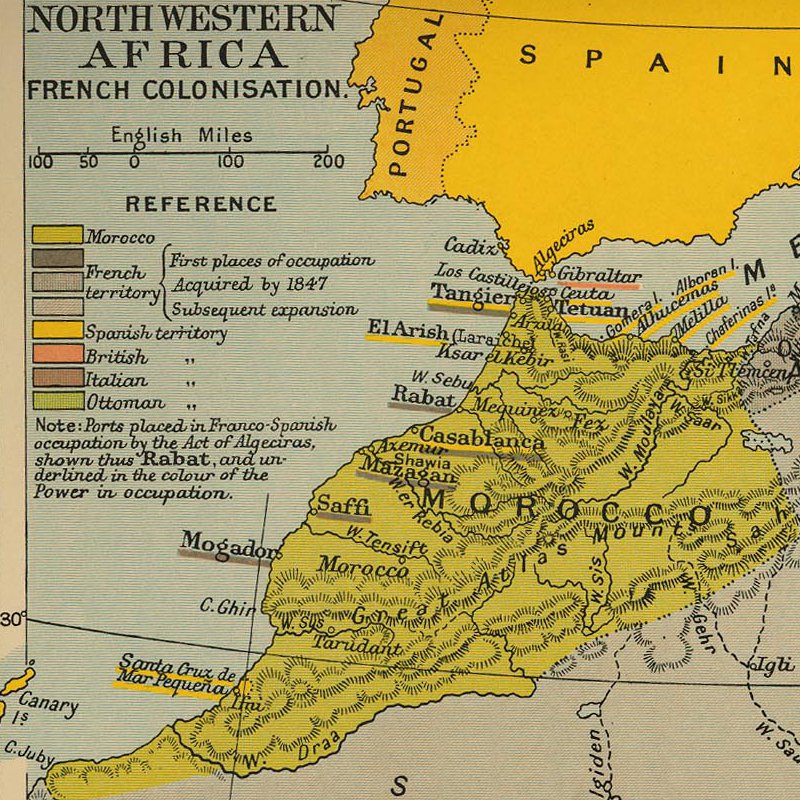

The assassination of Abdülhamid II presented the growing cadres of middle-ranking government officials committed to the Ottoman cause with a unique opportunity - but it was also a situation where they were once again the group that had the most to lose. They had already grown accustomed to the significant differences among the salaries of the different ranks of the administration, and to the fact that bribery was often a compulsory way to upkeep a lifestyle expected from their social status. They had been forced to put up with the nepotism of their examination and education system, and by 1905 the new priviledges enjoyed by the sons of most influential court members had already alienated and embittered the younger generations of technocrats in the armed forces and Ottoman administration. These young graduates from technical schools and military academies had entered to the odd and fascinating world of latest Western knowledge and cultural trends, but after receiving modern education in the cosmopolitan atmosphere of major cities of the empire these men were then shipped away to their first posts, virtually exiled to govern foreign barbarians to earn their spurs at the remote and backward tribal borderlands of the vast realm.

If they had proven themselves capable and they had had the right connections and/or enough luck, they could have eventually gained the necessary promotions to return to the heartlands of the Empire and rise to the coveted rank of a pasha. Each high-ranking pasha was at once an administrative expert and a political figure. Petitioning, persuading, sharing profits and outright bribing were common ways to influence their decisions at the provincial level, and foreigners had long ago learned how to take advantage of this system. The very nature of the Ottoman government pitted the officials against one another on determining how the limited tax funds should be used, and to function at all the administration depended on the existence of a supreme arbitrator, whether it was the Sultan or an influential Grand Vezir. By distributing the power powerful positions in the government among ambitious and competitive pashas, Abdülhamid II had managed to divide and rule by keeping the conflicting interests of his powerful advisors and bureaucrats in check. Upon his death the complex Byzantine web of court factions and bureaucracy the crafty Sultan had spun during his decades-long reign begun to unravel immediately. Several major figures had shared the reins of power by advising the Sultan on the problems that came to his attention, and controlling his access to individuals and information. Having schemed and waited for years on the shadows beneath the dominating dominating presence of the sultan, they were shocked to find themselves free to act, and take measures to strengthen their control of the Porte against the encroachments of competing political factions in the Ottoman society and the Palace itself. In the new situation some previously powerful figures were almost instantly sidelined, while others decided to take their chances and rose to challenge the prevailing status quo.

One of the previously highly esteemed positions that lost its significance upon the death of the Sultan was Sultan’s scribe (baş katip), who had presented all communications to the sultan and proposed laws and degrees. Over the centuries the scribes had expanded their official roles to a point where they had taken up the tasks of presenting to the sultan all communications and proposed laws and degrees, so that they had held the power to convey the sultan's will to to the various departments and government officials, and then communicate to him their own versions of the actual results. Therefore the scribe had held a strong influence to the way Abdülhamid II had viewed the surrounding world. As the Red Sultan was now dead, his long-standing scribe and trusted advisor Tahsin Pasha had lost his earlier influence virtually overnight.

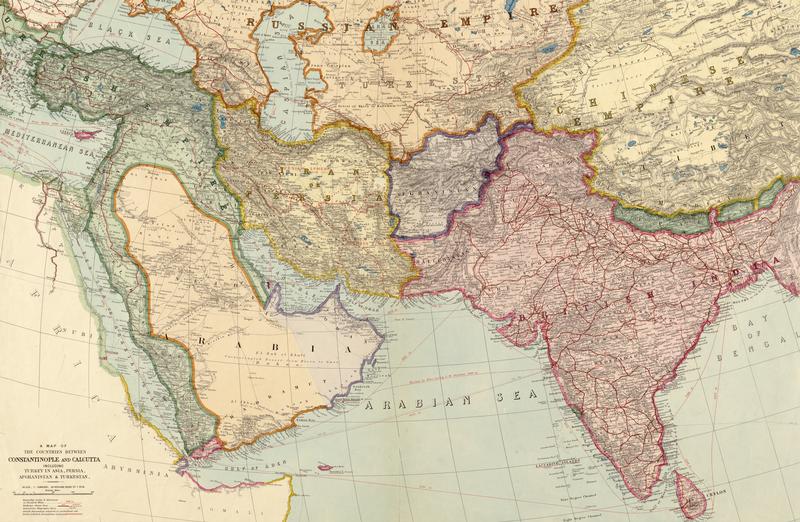

This benefitted the position of the Ottoman Chief of Staff, Ahmed Izzed Pasa. He had gradually elevated the importance of the traditionally ceremonial role of the secondary assistant scribe (kâtib-i-sani) by taking over the dull day-to-day affairs of the main scribe. By now he was firmly connected central figure in the Ottoman government with years of experience from the regular meetings with the Grand Vezir and ministers. There he had conveyed the wishes of the Sultan to them, received their reports, and then summarized their content to the main scribe and directly to the Sultan. By his dutiful service he had gained the trust of Abdülhamid II, and now chaired many important royal commissions, most importantly the financial reform commission and the commission established to deal with the problem presented by the British control of Egypt and Persian Gulf sheikdoms.

He also had a powerful ally in the current Grand Vezier, Mehmed Ferid Pasha. Both men were Tosk Albanians, and quickly found common ground in the upcoming power struggles against their Ottoman Turkish competitors. Like Ahmed Izzed Pasha, Mehmed Ferid Pasha had also been elevated through the ranks after he had gained the Sultan’s favour by his performance as the Governor of Konya. He was also the head of the Rumeli Reform Commission that had been established to deal with the deteriorating situation of Ottoman Macedonia in 1902. Aside from his native Albanian and Turkish the current Grand Vezier spoke French, Italian, Arabic and Greek. The Albanian Pashas combined the prestigious position of Grand Vezir to the influence of the Army, but they also had powerful competitors who had good contacts among the court and ruling elites.

Most prominent among them was Mehmed Said Pasha, who had exiled himself to a self-imposed house arrest and withdrawn from public life in 1903, fearing for reprisals of Abdülhamid II. Mehmed Said had been a Grand Vezir six times, and had shown unquestioned talent in matters of imperial administration. He had improved tax collection, balanced the budgets, led the negotiations about the settlement of Ottoman foreign debts, and modernized the examinations for civil service. Politically Mehmed Said was a dedicated Anglophile who opposed all foreign interference to Ottoman affairs, and a firm believer in centralized government and ample administration. To the other members of the Ottoman elite he was a dangerous, vainglorious, corrupt and extremely ambitious plotter who was loyal only to his own position.

The most serious challenger to Mehmed Ferid Pasha among the Ottoman Turkish elites was thus another former Grand Vezir, “The Cypriot” - Mehmed Kâmil Pasha. Mehmed Kâmil was also an anglophile and spoke fluent English. The foreign representatives in the capitol considered him to be a dignified person of integrity with an excellent grasp on world affairs, and among the Ottoman elites he had a reputation of an impartial elder statesman who preferred to focus on his duties instead of court bickering. Because of this he had been sidelined from the upper ranks of power. Personally Mehmed Kâmil was firmly dedicated to the Islamist policy pursued by the late Sultan. Known for his preference to adopt practical means to to preserve the state and secure its interests, Mehmed Kâmil had earlier written a controversial memorandum suggesting a redefinition of ministerial responsibilities and a new approach to the Armenian question.

As these men started to assess the chaotic situation during the first days after thea ssassination, they all sought to secure their positions against the alarmed and paralyzed security apparatus that Abdülhamid II had devised to protect his power. The key focus of their interest was the Privy Council (Yaveran-i-Ekrem) responsible for inspecting the army and civil service in order to ferret out "all dishonesty, disloyalty and inefficiency."In addition everyone was afraid of the Hafiye, secret police, that had been organized under the sultan’s personal control directed by one of his old protégés, Fehim Pasha. Army of spies and informants (jurnalcis) were present in every department of the government, and reported the actions and throughts of individual bureaucrats in memorandums (jurnals). Another key powerbroker was Sefik Pasha - head of the Zaptiye Nezareti, the Ministry of Police that was based on the French model. Commissioners (komisers) under the direct control of the minister directed police at each province and in the districts of Constantinye and other larger cities. These two police forces spied on one another and everyone else.

As the foreign representatives in the Ottoman capital were busily sending and receiving telegrams from the European capitals and the news of the assassination spread through the shocked Empire and the surrounding world, it was still too early to find a definitive answer to the fundamental question at hand: "Who would take charge after the death of Abdülhamid II?"