You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The March of Time - 20th Century History

- Thread starter Karelian

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Chapter 28: Anglo-Japanese Treaty

The Governments of Great Britain and Japan, being desirous of replacing the Agreement concluded between them on the 30th January, 1902, by fresh stipulations, have agreed upon the following Articles, which have for their object--

(a) The consolidation and maintenance of the general peace in the regions of Eastern Asia and of India;

(b) The preservation of the common interests of all Powers in China by insuring the independence and integrity of the Chinese Empire and the principle of equal opportunities for the commerce and industry of all nations in China;

(c) The maintenance of the territorial rights of the High Contracting Parties in the regions of Eastern Asia and of India, and the defence of their special interests in the said regions:--

Article I

It is agreed that whenever, in the opinion of either Great Britain or Japan, any of the rights and interests referred to in the preamble of this Agreement are in jeopardy, the two Governments will communicate with one another fully and frankly, and will consider in common the measures which should be taken to safeguard those menaced rights or interests.

Article II

If by reason of unprovoked attack or aggressive action, wherever arising, on the part of any other Power or Powers either Contracting Party should be involved in war in defence of its territorial right or special interests mentioned in the preamble of this Agreement, the other Contracting Party will at once come to the assistance of its ally, and will conduct the war in common, and make peace in mutual agreement with it.

Article III

Japan possessing paramount political, military, and economic interests in Corea, Great Britain recognizes the right of Japan to take such measures of guidance, control, and protection in Corea as she may deem proper and necessary to safeguard and advance those interests, provided always that such measures are not contrary to the existing international treaties and the principle of equal opportunities for the commerce and industry of all nations.[1]

Article IV

Great Britain having a special interest in all that concerns the security of the Indian frontier, Japan recognizes her right to take such measures in the proximity of that frontier as she may find necessary for safeguarding her Indian possessions.

Article V

The High Contracting Parties agree that neither of them will, without consulting the other, enter into separate arrangements with another Power to the prejudice of the objects described in the preamble of this Agreement.

Article VI

The conditions under which armed assistance shall be afforded by either Power to the other in the circumstances mentioned in the present Agreement, and the means by which such assistance is to be made available, will be arranged by the Naval and Military authorities of the Contracting Parties, who will from time to time consult one another fully and freely upon all questions of mutual interest.

Article VII

The present Agreement shall, subject to the provisions of Article VI, come into effect immediately after the date of its signature, and remain in force for ten years from that date.

The treaty also contains three secret notes:

Note A

Each of the Contracting Parties will endeavour to maintain at all times in the Far East a naval force superior in strength to that of any third European Power having the largest naval force in the Far East.[2]

Note B

In case Japan finds it necessary to establish [a] protectorate over Corea in order to check [the] aggressive action of any third Power, and to prevent complications in connection with [the] foreign relations of Corea, Great Britain engages to support the action of Japan[3]

[1]Slight alternation to OTL treaty text due the existence of the Yamagata-Muraviev Treaty of 1901.

[2] In OTL the destruction of Russian Pacific Fleet in the Russo-Japanese War made Britain reluctant to uphold this part of the treaty, especially since it would have now meant an obligation to keep up with the strength of the US Pacific Fleet. Here the Russian naval buildup in the Far East continues as planned, and this part of the treaty is upheld. In OTL the Japanese had no objection to the British revision of the Note to read "superior in strength to any European Power.

[3] Japan insisted upon this addition in exchange for her commitment to the defence of India, and the British government was willing to do it - in OTL there was a lot of support to the idea of getting involved to the Russo-Japanese war from the outset. Do note that the treaty does not specify the form of support Britain is expected to provide.

(a) The consolidation and maintenance of the general peace in the regions of Eastern Asia and of India;

(b) The preservation of the common interests of all Powers in China by insuring the independence and integrity of the Chinese Empire and the principle of equal opportunities for the commerce and industry of all nations in China;

(c) The maintenance of the territorial rights of the High Contracting Parties in the regions of Eastern Asia and of India, and the defence of their special interests in the said regions:--

Article I

It is agreed that whenever, in the opinion of either Great Britain or Japan, any of the rights and interests referred to in the preamble of this Agreement are in jeopardy, the two Governments will communicate with one another fully and frankly, and will consider in common the measures which should be taken to safeguard those menaced rights or interests.

Article II

If by reason of unprovoked attack or aggressive action, wherever arising, on the part of any other Power or Powers either Contracting Party should be involved in war in defence of its territorial right or special interests mentioned in the preamble of this Agreement, the other Contracting Party will at once come to the assistance of its ally, and will conduct the war in common, and make peace in mutual agreement with it.

Article III

Japan possessing paramount political, military, and economic interests in Corea, Great Britain recognizes the right of Japan to take such measures of guidance, control, and protection in Corea as she may deem proper and necessary to safeguard and advance those interests, provided always that such measures are not contrary to the existing international treaties and the principle of equal opportunities for the commerce and industry of all nations.[1]

Article IV

Great Britain having a special interest in all that concerns the security of the Indian frontier, Japan recognizes her right to take such measures in the proximity of that frontier as she may find necessary for safeguarding her Indian possessions.

Article V

The High Contracting Parties agree that neither of them will, without consulting the other, enter into separate arrangements with another Power to the prejudice of the objects described in the preamble of this Agreement.

Article VI

The conditions under which armed assistance shall be afforded by either Power to the other in the circumstances mentioned in the present Agreement, and the means by which such assistance is to be made available, will be arranged by the Naval and Military authorities of the Contracting Parties, who will from time to time consult one another fully and freely upon all questions of mutual interest.

Article VII

The present Agreement shall, subject to the provisions of Article VI, come into effect immediately after the date of its signature, and remain in force for ten years from that date.

The treaty also contains three secret notes:

Note A

Each of the Contracting Parties will endeavour to maintain at all times in the Far East a naval force superior in strength to that of any third European Power having the largest naval force in the Far East.[2]

Note B

In case Japan finds it necessary to establish [a] protectorate over Corea in order to check [the] aggressive action of any third Power, and to prevent complications in connection with [the] foreign relations of Corea, Great Britain engages to support the action of Japan[3]

[1]Slight alternation to OTL treaty text due the existence of the Yamagata-Muraviev Treaty of 1901.

[2] In OTL the destruction of Russian Pacific Fleet in the Russo-Japanese War made Britain reluctant to uphold this part of the treaty, especially since it would have now meant an obligation to keep up with the strength of the US Pacific Fleet. Here the Russian naval buildup in the Far East continues as planned, and this part of the treaty is upheld. In OTL the Japanese had no objection to the British revision of the Note to read "superior in strength to any European Power.

[3] Japan insisted upon this addition in exchange for her commitment to the defence of India, and the British government was willing to do it - in OTL there was a lot of support to the idea of getting involved to the Russo-Japanese war from the outset. Do note that the treaty does not specify the form of support Britain is expected to provide.

Last edited:

Thanks for the update, that is quite a commitment by Britain to Japan. The russian pacific fleet was not small. However, they can of course handle it, but it really shows how highly London value Japan as a guarentee of security. Japan has become much more integral to british security than OTL.

Thanks for the update, that is quite a commitment by Britain to Japan. The russian pacific fleet was not small. However, they can of course handle it, but it really shows how highly London value Japan as a guarentee of security. Japan has become much more integral to british security than OTL.

I should emphasize that the treaty text is 95% OTL stuff:

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=PBH19050928.2.24

Britain valued Japan as a counterweight to Russia, and by the time of the OTL renewal of the treaty the Russian Empire hadn't still experienced the postwar revolutionary activities that changed the earlier image of Russia as an imposing juggernaught of an empire to a internally divided power that was struggling to keep up with the changing world around it. Without the Russo-Japanese War, that image remains intact, and it does little to diminish British fears - although they are increasingly confident that as long as Persia and Afghanistan remain remote backwaters, the North-Western Frontier is safe from Russian incursions.

Hi!

Just find your thread and enjoy it.

Thanks for the feedback, it motivates me to keep this up.

There's an update on the works as well, so stay tuned.

There's an update on the works as well, so stay tuned.

Great. I've just caught up, and I'm very impressed with the depth of research.

One side point: if you repost this to the Completed TLs board, it could use profing and editing by an English speaker. There are a lot of glitches.

Great. I've just caught up, and I'm very impressed with the depth of research.

One side point: if you repost this to the Completed TLs board, it could use profing and editing by an English speaker. There are a lot of glitches.

Definitively. A lot of the updates were originally made without automatic grammar assistance, and it really shows.

Chapter 29: The Macedonian Crisis, part VII: The Thunder of St.Vitus

The Macedonian Crisis, part VII: The Thunder of St.Vitus

The tumult and chaos caused by the assassination of Sultan Abdülhamid II spread out from the Ottoman capital to two major directions: West to Macedonia, and East to eastern Anatolia. In many ways the events mirrored the incidents of earlier Hamidian massacres. First wild rumours spread out from the capitol about the death of the Sultan, naming Armenian terrorists as the likely assassins. It did not take long before angry mobs of local Kurdish and Turkish Muslims begun a series of spontaneous and disorganized attacks against local Armenian communities. Unrest broke out in Constantinople and soon afterwards engulfed the rest of the Armenian-populated vilayets. As Bitlis, Diyarbekir, Erzurum, Sivas, Trebizond, Van and Mamurel-ul-Azizvilayets burned, the Ottoman government was hard-pressed to regain control, and the reactions of the various government officials were more or less arbitrary - some stood by, while others did everything in their power to stop the violence. The Vali of Van, Tahsin Bey, was the only high-ranking Ottoman official who got the situation under control. He had already stabilized his vilayet with a harsh policy of executing the most notorious bandit leaders publicly soon upon their capture, and was in a middle of dealing the resistance of local Kurdish tribes when the rioting begun. As soon as he realized the scope of the events shaking the whole realm, he adopted an equally ruthless line towards the Kurdish aghas who defied his rule. One of the local aghas, Sheikh Taha, used his tribal forces to loot and assault Armenian settlements. In response Tahsin Bey sent in regular Ottoman troops with artillery support to shell the two villages held by Tahsin Bey and his men, killing over twenty of his kinsmen and followers and forcing the rest to flee from their homes and away from the vilayet. He also dispersed the two-thousand strong tribal community of recently emigrated Manhoran Kurds back to the eastern Kurdish border villages, and returned the villages of Soraderi, Parei, Bablasani, Sorani and Haradoun to the Armenian peasants who the Kurds had driven away earlier. But while Tahsin Bey and some mid-level Ottoman government officials truly did their best to prevent violence against the Armenians and other Christian minorities, the paralysis of local government and long-standing resentment against Armenians among local Muslims ensured that thousands of Armenians lost their lives and tens of thousands were forced to internal exile. Yet it was not a story of innocent victims and ruthless oppressors. Armed groups of ARF Ֆէտայի (fedayi) were also widely active in the six Armenian vilayets, striking against Ottoman troops, Kurdish militias and common Muslim civilians where- and whenever possible.

The situation in Anatolia would have been bad enough in itself, but there was more to come. A few days after the death of the Sultan, the factions of IMARO that had cooperated with Armenian ARF sent out the word to their fighters all around Ottoman Macedonia. And on the 28th of July, the fire of revolution flared up in Macedonia as IMARO started their long-awaited uprising in the Ottoman Balkan provinces. The uprising started with attacks against Ottoman infrastructure: railroads, bridges, tunnels, gas works, banks and police and army installations were attacked with dynamite-wielding rebels. The actual fighting began when the rebel bands moved out from their highland hideouts to capture the key narrow mountain passes. After severing lines of communication in this fashion on several valleys, they then proceeded to attack the now-isolated police and military outposts one at a time with overwhelming force. Among the victims of these early raids was a promising young Yüzbaşı Enver Pasha. As the rebels gained ground during the initial confusion, their bands dispersed to the countryside, terrorizing the local Muslim villages with murders and widespread looting. The Greek fighters operating in southern Macedonia were not amused of the uprising that they saw as a direct challenge to their own aspirations, and after a few days the region was engulfed to a multi-sided civil war, where the Ottoman authorities desperately sought to suppress all revolutionary activities. The Army was ordered to keep the roads open and population centers under control, while the opposed nationalist groups fought their own battles against the government forces and one another in the mountains. While the rebels often waved Bulgarian flags and naively expected Sofia to enter the fray sooner rather than later, the Bulgarian government had no intent to repeat the Greek mistake of 1897 and fight a war against the Ottomans without outside help. The leaders of Bulgaria merely wished to use internal dissent in Macedonia and the general threat of war to force the Great Powers to support their bid for independence, unification with Eastern Rumelia and to gain support for further Bulgarian demands of local autonomy for Macedonia. This policy had been further strengthened by the Russo-Bulgarian military alliance on 14th of June 1902, officially aimed against Romanian attack, but in reality giving Sofia guarantees against Ottoman military aggression as well. But since the events were an unpleasant surprise to the Russian government, Bulgarian authorities did not want to take any unnecessary risks, and preferred to wait how the Powers would react to the crisis in the Balkans.

The destruction and violence in eastern Anatolia worked like the Armenian revolutionary leaders had (cynically) predicted - the news of new massacres and battles were enough to draw in considerable foreign attention. The Armenians hoped that this would finally lead to the implementation of reforms agreed upon on the Treaty of Berlin of 1878. Its article 61, never put into practice, had established that the European powers would guarantee the implementation of administrative reforms within the provinces of the Empire inhabited by Armenians. Now, as the European newspapers were quick to point out, the situation in Anatolia was just like in China a few years earlier: brave European communities and local Christian minorities were under siege by ‘heathen barbarians’. There situation was indeed disturbingly similar to the beginning of the Boxer War. Foreign naval forces had begun to gather to Aegean after July 21st, just like they had appeared to the coasts of China five years earlier. The European leaders had no illusions about the gravity of the situation. If violence in Asia Minor escalated out of hand, it was feared that Russia would be compelled to stage an armed intervention, which would in turn surely be met by Austrian counteraction in the Balkans. The threat of escalation to a general European war suddenly turned the chaos of Macedonia and the continued well-being and survival of Armenians and other Eastern Christian minority groups in Ottoman Anatolia into a tense international crisis, that the Major Powers urgently sought to solve through diplomatic means before it would be too late.

The tumult and chaos caused by the assassination of Sultan Abdülhamid II spread out from the Ottoman capital to two major directions: West to Macedonia, and East to eastern Anatolia. In many ways the events mirrored the incidents of earlier Hamidian massacres. First wild rumours spread out from the capitol about the death of the Sultan, naming Armenian terrorists as the likely assassins. It did not take long before angry mobs of local Kurdish and Turkish Muslims begun a series of spontaneous and disorganized attacks against local Armenian communities. Unrest broke out in Constantinople and soon afterwards engulfed the rest of the Armenian-populated vilayets. As Bitlis, Diyarbekir, Erzurum, Sivas, Trebizond, Van and Mamurel-ul-Azizvilayets burned, the Ottoman government was hard-pressed to regain control, and the reactions of the various government officials were more or less arbitrary - some stood by, while others did everything in their power to stop the violence. The Vali of Van, Tahsin Bey, was the only high-ranking Ottoman official who got the situation under control. He had already stabilized his vilayet with a harsh policy of executing the most notorious bandit leaders publicly soon upon their capture, and was in a middle of dealing the resistance of local Kurdish tribes when the rioting begun. As soon as he realized the scope of the events shaking the whole realm, he adopted an equally ruthless line towards the Kurdish aghas who defied his rule. One of the local aghas, Sheikh Taha, used his tribal forces to loot and assault Armenian settlements. In response Tahsin Bey sent in regular Ottoman troops with artillery support to shell the two villages held by Tahsin Bey and his men, killing over twenty of his kinsmen and followers and forcing the rest to flee from their homes and away from the vilayet. He also dispersed the two-thousand strong tribal community of recently emigrated Manhoran Kurds back to the eastern Kurdish border villages, and returned the villages of Soraderi, Parei, Bablasani, Sorani and Haradoun to the Armenian peasants who the Kurds had driven away earlier. But while Tahsin Bey and some mid-level Ottoman government officials truly did their best to prevent violence against the Armenians and other Christian minorities, the paralysis of local government and long-standing resentment against Armenians among local Muslims ensured that thousands of Armenians lost their lives and tens of thousands were forced to internal exile. Yet it was not a story of innocent victims and ruthless oppressors. Armed groups of ARF Ֆէտայի (fedayi) were also widely active in the six Armenian vilayets, striking against Ottoman troops, Kurdish militias and common Muslim civilians where- and whenever possible.

The situation in Anatolia would have been bad enough in itself, but there was more to come. A few days after the death of the Sultan, the factions of IMARO that had cooperated with Armenian ARF sent out the word to their fighters all around Ottoman Macedonia. And on the 28th of July, the fire of revolution flared up in Macedonia as IMARO started their long-awaited uprising in the Ottoman Balkan provinces. The uprising started with attacks against Ottoman infrastructure: railroads, bridges, tunnels, gas works, banks and police and army installations were attacked with dynamite-wielding rebels. The actual fighting began when the rebel bands moved out from their highland hideouts to capture the key narrow mountain passes. After severing lines of communication in this fashion on several valleys, they then proceeded to attack the now-isolated police and military outposts one at a time with overwhelming force. Among the victims of these early raids was a promising young Yüzbaşı Enver Pasha. As the rebels gained ground during the initial confusion, their bands dispersed to the countryside, terrorizing the local Muslim villages with murders and widespread looting. The Greek fighters operating in southern Macedonia were not amused of the uprising that they saw as a direct challenge to their own aspirations, and after a few days the region was engulfed to a multi-sided civil war, where the Ottoman authorities desperately sought to suppress all revolutionary activities. The Army was ordered to keep the roads open and population centers under control, while the opposed nationalist groups fought their own battles against the government forces and one another in the mountains. While the rebels often waved Bulgarian flags and naively expected Sofia to enter the fray sooner rather than later, the Bulgarian government had no intent to repeat the Greek mistake of 1897 and fight a war against the Ottomans without outside help. The leaders of Bulgaria merely wished to use internal dissent in Macedonia and the general threat of war to force the Great Powers to support their bid for independence, unification with Eastern Rumelia and to gain support for further Bulgarian demands of local autonomy for Macedonia. This policy had been further strengthened by the Russo-Bulgarian military alliance on 14th of June 1902, officially aimed against Romanian attack, but in reality giving Sofia guarantees against Ottoman military aggression as well. But since the events were an unpleasant surprise to the Russian government, Bulgarian authorities did not want to take any unnecessary risks, and preferred to wait how the Powers would react to the crisis in the Balkans.

The destruction and violence in eastern Anatolia worked like the Armenian revolutionary leaders had (cynically) predicted - the news of new massacres and battles were enough to draw in considerable foreign attention. The Armenians hoped that this would finally lead to the implementation of reforms agreed upon on the Treaty of Berlin of 1878. Its article 61, never put into practice, had established that the European powers would guarantee the implementation of administrative reforms within the provinces of the Empire inhabited by Armenians. Now, as the European newspapers were quick to point out, the situation in Anatolia was just like in China a few years earlier: brave European communities and local Christian minorities were under siege by ‘heathen barbarians’. There situation was indeed disturbingly similar to the beginning of the Boxer War. Foreign naval forces had begun to gather to Aegean after July 21st, just like they had appeared to the coasts of China five years earlier. The European leaders had no illusions about the gravity of the situation. If violence in Asia Minor escalated out of hand, it was feared that Russia would be compelled to stage an armed intervention, which would in turn surely be met by Austrian counteraction in the Balkans. The threat of escalation to a general European war suddenly turned the chaos of Macedonia and the continued well-being and survival of Armenians and other Eastern Christian minority groups in Ottoman Anatolia into a tense international crisis, that the Major Powers urgently sought to solve through diplomatic means before it would be too late.

Last edited:

How is the situation in the Arab territories? Calm or is there persecution against Arab Christians too?

The sectarian war between Druzes and Maronites in Lebanon ended after an European intervention 40 years ago, the Règlement Organique degrees are still in force, and the situation is consequently relatively peaceful. The situation in northern Syria and Mesopotamia will be covered in future updates in greater detail.

Chapter 30: The Macedonian Crisis, part VIII: Conflicts of Interest

The Macedonian Crisis, part VIII: Conflicts of Interest

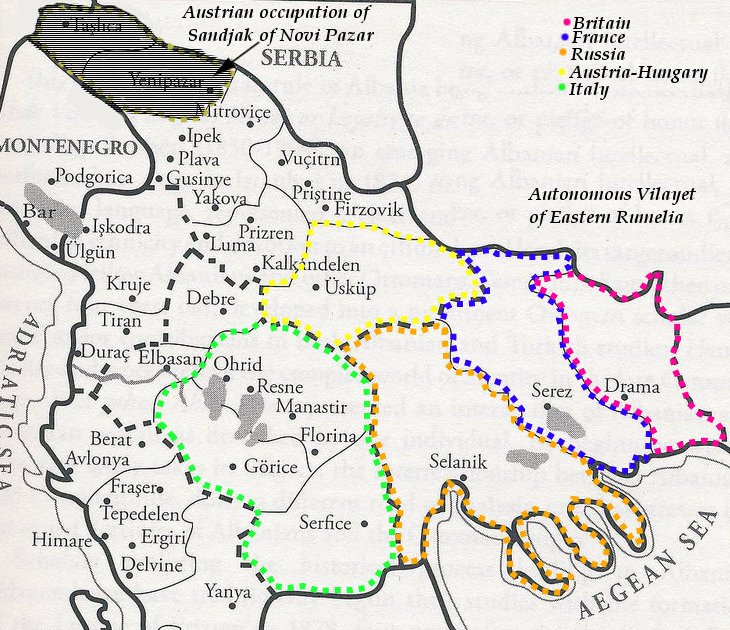

The main obstacles for a swift foreign intervention to the Ottoman territories were the conflicting aims of the Major Powers. This made the current crisis difficult to dissolve without a solution that would leave at least one of the Powers dissatisfied with the outcome. Yet every one of them wanted see the situation dealt with in some manner out of the fear that the crisis would otherwise escalate out of control,, and as a consequence the region witnessed attempts to conduct similar joint diplomacy that had stabilized the Balkans with the Treaty of Berlin. Austria-Hungary and Russia, the two traditionally dominant powers in the peninsula led the way in the issue of Macedonia.Their cooperation on the matter was based on the Mürzsteg Program that had been jointly formulated two years earlier, in July 1903. The original reform program had envisioned restructuring of the Ottoman Jandarma (gendarmerie) and civil government in the Macedonian vilayets, where the local law enforcement was to be commanded a European general and lower-ranking foreign officers. Additionally Vienna and St.Petersburg had agreed that local Christian civil servants and judicial officials would have to be appointed and installed to governmental structure with numbers that would proportionally represent the Christian population of the Macedonian provinces. These reforms were to be conducted under Russian and Austro-Hungarian supervision, but due Ottoman delaying tactics the first foreign commissioners were just preparing to move in when the Macedonian Uprising begun. Now other Powers with interests towards the region were suddenly eager to offer their help.

Tommaso Tittoni, the ambitious Foreign Minister of Italy, was especially active. He saw the crisis in Macedonia as chance for improving Italian prestige in the region, and for mending fences with Austria-Hungary and France. The official purpose of the Rome Conference that he arranged a few weeks after the assassination was to find a solution to the recent troubles in the Ottoman Empire. As this goal was shared by all of the powers, the initial negotiations were indeed conducted in a serious, cooperative manner. It was agreed that an Italian general, de Giorgis, would lead the new Macedonian Jandarma. The twenty-five officers serving under his command were recruited from all parts of Europe. As a new development the Macedonian territories subjected to the current unrest were divided into five areas of responsibility: Austria-Hungary would administer Üsküp, Italian officers would supervise Manastir, Russians were to take care of Salonika and France and Great Britain would take responsibility of Serez and Drama. The Germans were eager to participate, but since Berlin still wanted to portray themselves as friends of the Porte, they opted to set up a school for Jandarma officers and government officials in Salonica instead of a zone of their own.

Unofficially every Power had arrived to Rome with the aim of at least protecting their existing interests, and perhaps even gaining benefits from the new situation at the expense of their rival. So although the Powers were now in general agreement about the future of Ottoman Macedonia, the Conference soon met an impasse in negotiations about the enforcement and swift implementation of their new demands. Maurice Rouvier, the cautious French Premier, was against naval demonstrations by only one side, even if they were conducted by their Russian allies: "it seems certain to me that such despatch [of Russian ships to Constantinople] would have the immediate consequence of a naval action by the Triple Alliance in the same regions, if not at least a military action by Austria-Hungary.”French representatives were also unwilling to support the second Russian diplomatic proposal, a financial boycott of the Ottoman Empire. The reasons for French reluctance were economical. French finance controlled the largest part of the Ottoman public debt, and in addition French finances enjoyed the benefits of several Unequal Treaties with the Ottoman state. The one most hated by the locals was the monopoly position of the Régie Company. Backed by a consortium of powerful European bankers, the Société de la régie co-intéressée des tabacs de l'empire Ottoman had legal monopoly of tobacco production and salt taxes in the Ottoman realm. The company had a reputation of using bribed Ottoman Jandarma units and local thugs to enforce their tobacco monopoly and salt taxation with impunity. But as hated as it was by the Ottoman society in general, the company had so far been able to operate without serious challenges from the Porte due the fact that it provided hundreds of thousands of francs worth of revenue for the Ottoman government - and to the foreign shareholders. Premier Pichon was afraid that it would be France's responsibility to compensate to the European shareholders for any losses incurred due the private nature of the original contract of Régie, and the French diplomats were thus unwilling to even contemplate any boycotts or trade embargoes.

Other Powers were equally doubtful about the sincerity of Russian proposal. After all, Russia had no capital investments or railway concessions to worry about, and wasn’t represented on the Ottoman Public Debt Administration either. Therefore the French delegates in the Conference found themselves from a strange position: they were in essence supporting the same approach as Berlin. With France and Germany opposing coercive action Britain hoping to get the Powers to act in unison, the negotiations were getting nowhere. With the initial violence winding down in Eastern Anatolia and the Ottoman Army gaining the upper hand in the battles against the rebel groups in Macedonia, some participants actually preferred to wait a bit “until the dust settles down.” When Goluchowski, the Austro-Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs known for his earlier attempts to improve the Austro-Russian relations then contacted Count Muraviev, the two Empires quickly found a common stance on the matter, promoting joint naval demonstration by all the Powers. After Italy joined in to promote this course of action, Germans reluctantly joined in as well, mainly to avoid a situation where the two members of the Triple Alliance would be in opposition to a viewpoint jointly supported by France and Germany. Soon information leaks from the negotiations spread out to European media, and the position of French Foreign Minister Théophile Delcassé became untenable. His reluctance to reach a compromise that would put French interests in Ottoman Empire in jeopardy and damage his carefully planned policy in Morocco was spinned into anti-Armenian hostility in the French press, and he was soon forced to leave office. As Premier Rouvier, France quickly rallied to support the forming European coalition to avoid further damage to her international reputation and prestige. The ships of the international fleet that had gathered to Dardanelles steamed forth, towards the port city of Mytilene, and island of Lesvos and Limnos. By seizing the customs house of Limnos they captured an area vitally important to the defence of the city of Constantinople, equidistant between the north Aegean coast of Macedonia and the northeastern coast of Asia Minor; from its location, all maritime traffic heading to or from the Dardanelles could be intercepted. Now the Powers had leverage, and they presented a joint ultimatum to the Porte on 21st of August 1905.

Last edited:

Pichon as premier! I guess he did well in China to catapult his career!

If I don't misremember he held French interests in Syria especially high.

Actually that's a typo, Maurice Rouvier is still the Premier.

Pichon replaces Delcassé though, so his career is definitively in the upswing.

Actually that's a typo, Maurice Rouvier is still the Premier.

Pichon replaces Delcassé though, so his career is definitively in the upswing.

Ah, I see. Speeded up by one year then.

Chapter 31: The Macedonian Crisis, part IX: The August Ultimatum

The Macedonian Crisis, part IX: The August Ultimatum

The August Ultimatum was a mixed blessing to the high-ranking Armenian officials in the Ottoman Empire, especially to the religious leader of the Armenian millet, Catholicos Mkrtich I. While he had privately lost his trust to European powers after the Treaty of Berlin, the Catholicos had ever since discreetly cooperated with Boghos Nubar Pasha, the chairman of the Armenian National Assembly. Together these two influential Armenians in the Ottoman Empire had established close contacts to the Albanian Pashas[1], who had by now secured their current grip of power and recovered from the worst initial shock of the assassination enough to start determined efforts to restore order in eastern Anatolia. Boghos Nubar Pasha had also using his foreign contacts to get European powers to stage a military intervention in order to finally facilitate the reforms of the Nizâmnâme-i Millet-i Ermeniyân (Regulation of Armenian Nation) documents of 1863. Armenian diaspora across the globe had also been active, keeping the topic of imperiled Armenians on daily headlines. Speeches had held at the British parliament, German Reichstag and in the Italian Chamber of Deputies. Newspapers had written articles demanding action, and public interest toward the situation in the Ottoman Empire had steadily grown around Europe through the summer. The matter had been especially important for the Russian government, since the local situation between the Armenians of Russian Caucasus and the Muslim Tatars was on a verge of a disaster. The unrest on the Ottoman side of the border was spilling over to Transcaucasus, as waves of new refugees and the increased activity of Dashnak militias kept deteriorating the local security situation.[2]

Catholicos Mkrtich I. The widely respected old Patriarch had tried to ease the situation of average Anatolian Armenian peasants through his whole life. But since he had been bitterly disappointed by Western indifference after the Treaty of Berlin, in 1905 he was first and foremost trying to avoid a situation where too open political support to foreign support or Armenian revolutionary groups would lead to a wide governmental repression of average Armenians.

The ultimatum was also met with mixed feelings by the Western representatives and Ambassadors in Constantinopole. The most respected member of the diplomatic community in the City was the British Ambassador, Sir Nicholas O’Conor. As a respected senior diplomat, he had already served Britain in various important missions during his long career. He had departed from China a few years before the outbreak of the Boxer War, and during his tenure there Lord Curzon had complimented his work as "a man who really knew both the country to which he was accredited and the business which he would have to transact there." being able and forceful in pressing British interests. In addition to China, O'Conor also had experience from the Balkans. In 1887 he had been appointed the Agent and Consul-General in Bulgaria for five years. He was also no stranger to Russian politics, a fact that influenced his views considerably during the current crisis. Having served as the British Ambassador at St. Petersburg from 1895 to 1898, he had been a central figure in the Anglo-Russian diplomatic feuds over the Russian occupation of Port Arthur. In December, 1897 he had been instructed by Lord Salisbury to obtain from Count Muraviev assurances that Port Arthur and Talienwan should, like the other Treaty Ports of the Chinese Empire, be freely open to foreign trade. Seeing the following development and the situation in China as a proof of Russian dishonesty, O'Conor was strongly opposed to solutions that would "put British interests in jeopardy." His colleague, Heinrich von Calice, the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in Constantinople, was also weary of sudden moves. He had also served in China and Japan, and had already gained reputation of such pragmatism and understanding of Ottoman views that Goluchowski, his superior, had little sympathy for his current ambassador and doubted his capacity to be firm towards the Ottomans : "The old buffer at Constantinople has become so oriental as to be perfectly tolerant of Turkish methods..." The German diplomats were also reluctant to do a complete turnabout of their policy towards the Ottoman Empire, and thus the German diplomacy towards the Armenian Question had been conducted on both sides of the street, so to speak. With tacit British approval, German Foreign Minister von Richthofen had labored hard in the Rome Conference to secure a settlement that would be least subversive of Ottoman sovereignty as possible, while still securing protections for the Armenian minority to settle down public opinion back home. At the same time he had used the legendary Johannes Lepsius, who had made the situation of Armenians widely known in Germany a decade earlier to open unofficial contacts to the Armenian leaders. This way von Richthofen both hoped to win them over to a compromise, while maintaining the goodwill of the new Ottoman regime in the eventuality of a breakdown of negotiations.

The German activities in Rome Conference had alarmed the Russian leadership a great deal. They remembered well how von Bismarck had presented himself as a "honest broker", and then created a European coalition of other Powers to enforce the Treaty of Berlin, putting the Balkans on ice despite the stunning Russian victories over the Ottomans. Since then Russia had sought to prolong the backwardness and isolation of the eastern Anatolian lands as a defensive buffer covering the recently conquered and volatile Transcaucasus. In addition the Russian generals and diplomats had hoped that the lack of good infrastructure would also act as a barrier to foreign competition in Persia, a land that many Russian leaders viewed as a key to the future economic penetration of the Levant. But the Germans had declined to conclude formal agreements with Russia regarding future spheres of interest in the region. They had merely persuaded the Ottoman regime to direct the route of the new Anatolian Railway southwards, away from the Russian frontiers and the Black Sea coast. Ambassador Zinoviev had then quickly obtained the Sultan’s agreement not to grant further railway construction concessions to foreign powers north of a line between Kaiseri, Diarbekir, Sivas and Kharput. This attitude was still present in the contents of the new Russian proposal that they brought forth as a solution in the Rome Conference. The new reform project had been prepared by André Mandelstam, the dragoman (translator) at the Russian Embassy in Constantinople in cooperation with Nubar Pasha and other representatives from the Armenian National Assembly. Ivan Zanriev, a Dashnak leader with good connection in ruling circles in St. Petersburg had also played a decisive role in expressing Armenian views and hopes to the Russians. Mandelstam himself was a protégé of Fedor Martens, the leading Russian scholar of international law, and a close colleague of Boris Nolde, head of the Legal Advisory Office in the Russian Foreign Ministry. Thus the proposal was in essence a legally impressive and carefully crafted Armenian reform wishlist mixed together with a plan that aimed to secure Russian geopolitical goals in the region.

The contents of the August Ultimatum were developed in close cooperation with Boghos Nubar Pasha and his colleagues.

Armenian language was to be given legal position in education and local administration, special commissions would be organized to examine local cases of land confiscation with the power to expel recently established Muslim refugee groups when necessary. The Hamidiye irregular cavalry regiments were to be disbanded. Previously designated six Armenian vilayets (Bitlis, Diarbekir, Erzerum, Mamuret-el-Aziz, Sivas, and Van) were to be united together to form a single province, administered by jandarma commanded by European officers and led by either an Ottoman Christian or a European governor general supported by local advisory council with representatives of all local religious groups. This official would be appointed by the European powers for the next five years to oversee matters related to Armenian issues. Finally the treaty would obligate the Powers to enforce the implementation of the reforms.

Before it was officially represented to the conference at Rome, the project was introduced and discussed at a private meeting of the French, British and Italian ambassadors. The Russian representatives emphasized the fact that their government sought to avoid any measures that might antagonize the Ottomans. Count Muraviev himself truly believed that pressing the reform project too harshly might provoke the Ottoman regime or the local population to desperate measures. He tried to convince the other Powers in Rome that Russia had too many internal troubles with her current Armenians to contemplate further annexations of Ottoman territory in Anatolia.[3] But while the representatives of other Powers came to recognize the sincerity of Russian statements that they contemplated no territorial expansion, they still pointed out that the Mandelstam Plan would still lead inevitably to that outcome. The Russians were quick to answer that in a case that the Mandelstam Plan would not be adopted, the region would descend into a civil war, thus forcing the Russians to conduct a military intervention. Thus the Russian diplomats indirectly and quite bluntly implied that that without her plan partition would result. The German delegation asserted that partition would result directly from the plan itself. British diplomats agreed that the Mandelstam Plan looked too much like the beginning of partition to be allowed - the cure was worse than the disease, and British policymakers were worried on the possible effects the partition of Ottoman Empire would have on their Indian Muslim subjects. The Ottoman government was terrified to find out the content of the original draft via diplomatic leaks and trusted informants, and sought vigorously to alter it, seeking to play the mutual distrust and disagreements of the Powers against one another. The Ottoman leaders knew that they held one trump card: the general desire of the Powers was that the Ottoman Empire would - at least for now - survive intact as a political entity. They also drafted their own counter-proposal that was centered around the idea of a network of inspector-generals.

Ultimately the German strong opposition to original Russian draft succeeded in obtaining several important modifications, such as the division of the region into two provinces headed by inspector-generals, who still would (to the dismay of the Ottoman government) have the authority to appoint and relieve relieve provincial officials and bureaucrats as they saw fit. They would be posted in Van and Erzerum. The counterproposal was largely agreed, and St. Petersburg merely instructed Russian diplomats to insist on three points: The 50-50 principle of local leadership be applied to vilayet of Erzerum, that Muhacir (Muslim refugees from Balkans and Caucasus) would be prohibited from entering the territory of Armenian Vilayet and that local Christians would be guaranteed a place on the general councils in Harput, Dyarbekir and Sivas. Just like in Macedonia, the actual situation in the area ensured that the new administration would face an impossible task in trying to define "just" ethnic and religious borders and administrative divisions.

The main problem of Armenians and non-Armenian Christian minority groups in Ottoman Empire in 1905 were their geographical divergence - they were a sizeable minority in a lot of places, but a majority in only a few areas. The Nestorian Christians were even more diverse lot than Armenians. Some of them were urban city-dwellers, while others existed in feudal agrarian settings in tribal mountaineer societies like the Nestorians of Hakkari Mountains.The total population of Oriental churches in Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia in the regions of Diyarbekir, Van, Bitlis, Urfa, Der Zor, Mosul and Urmia numbers roughly ~600 000 people, with Nestorians being the largest church with just under 200 000 members:

Assyro-Chaldeans (East Syriac): 190 000

Assyro-Chaldeans (West Syriac): 133 000

Chaldean Church (Uniate church with Roman Catcholic Church from 1681): 100 000

Syriac Catholic: 5,600

Armenian Catholic: 12,500

Syriacs in northern parts of Van, Bitlis-Sivas, Harput: 56 000

This statistic excludes the Aramean populations in the greater part of Syria, Lebanon and Palestine.

1. Mehmed Ferid Pasha and Ahmed Issed Pasha:https://www.alternatehistory.com/discussion/showpost.php?p=10037899&postcount=171

2. In OTL the unrest had a lot to do with the general restlessness of Russian society in 1905. But Caucasus was a hotbed of ethnic violence and terrorism already before the Russo-Japanese War.

3. After Manchuria, it is not surprising that other Powers have little trust on Russian statements regarding their territorial ambitions. But ironically this time Muraviev truly means what he says. In OTL Russian government consistently maintained the view that Ottoman regime would retain formal sovereignty over Armenian vilayets up to the early years of WW1! Basic Principles for the Future Ordering of Armenia, published in 1915: “the formation of an autonomous Armenia under the sovereignty of the Sultan and under the tripartite protectorate of Russia, France and England would be the natural result of the longstanding favorable attitude not only of Russia, but of its Allies as well, toward the Turkish Armenians.”

The August Ultimatum was a mixed blessing to the high-ranking Armenian officials in the Ottoman Empire, especially to the religious leader of the Armenian millet, Catholicos Mkrtich I. While he had privately lost his trust to European powers after the Treaty of Berlin, the Catholicos had ever since discreetly cooperated with Boghos Nubar Pasha, the chairman of the Armenian National Assembly. Together these two influential Armenians in the Ottoman Empire had established close contacts to the Albanian Pashas[1], who had by now secured their current grip of power and recovered from the worst initial shock of the assassination enough to start determined efforts to restore order in eastern Anatolia. Boghos Nubar Pasha had also using his foreign contacts to get European powers to stage a military intervention in order to finally facilitate the reforms of the Nizâmnâme-i Millet-i Ermeniyân (Regulation of Armenian Nation) documents of 1863. Armenian diaspora across the globe had also been active, keeping the topic of imperiled Armenians on daily headlines. Speeches had held at the British parliament, German Reichstag and in the Italian Chamber of Deputies. Newspapers had written articles demanding action, and public interest toward the situation in the Ottoman Empire had steadily grown around Europe through the summer. The matter had been especially important for the Russian government, since the local situation between the Armenians of Russian Caucasus and the Muslim Tatars was on a verge of a disaster. The unrest on the Ottoman side of the border was spilling over to Transcaucasus, as waves of new refugees and the increased activity of Dashnak militias kept deteriorating the local security situation.[2]

Catholicos Mkrtich I. The widely respected old Patriarch had tried to ease the situation of average Anatolian Armenian peasants through his whole life. But since he had been bitterly disappointed by Western indifference after the Treaty of Berlin, in 1905 he was first and foremost trying to avoid a situation where too open political support to foreign support or Armenian revolutionary groups would lead to a wide governmental repression of average Armenians.

The ultimatum was also met with mixed feelings by the Western representatives and Ambassadors in Constantinopole. The most respected member of the diplomatic community in the City was the British Ambassador, Sir Nicholas O’Conor. As a respected senior diplomat, he had already served Britain in various important missions during his long career. He had departed from China a few years before the outbreak of the Boxer War, and during his tenure there Lord Curzon had complimented his work as "a man who really knew both the country to which he was accredited and the business which he would have to transact there." being able and forceful in pressing British interests. In addition to China, O'Conor also had experience from the Balkans. In 1887 he had been appointed the Agent and Consul-General in Bulgaria for five years. He was also no stranger to Russian politics, a fact that influenced his views considerably during the current crisis. Having served as the British Ambassador at St. Petersburg from 1895 to 1898, he had been a central figure in the Anglo-Russian diplomatic feuds over the Russian occupation of Port Arthur. In December, 1897 he had been instructed by Lord Salisbury to obtain from Count Muraviev assurances that Port Arthur and Talienwan should, like the other Treaty Ports of the Chinese Empire, be freely open to foreign trade. Seeing the following development and the situation in China as a proof of Russian dishonesty, O'Conor was strongly opposed to solutions that would "put British interests in jeopardy." His colleague, Heinrich von Calice, the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in Constantinople, was also weary of sudden moves. He had also served in China and Japan, and had already gained reputation of such pragmatism and understanding of Ottoman views that Goluchowski, his superior, had little sympathy for his current ambassador and doubted his capacity to be firm towards the Ottomans : "The old buffer at Constantinople has become so oriental as to be perfectly tolerant of Turkish methods..." The German diplomats were also reluctant to do a complete turnabout of their policy towards the Ottoman Empire, and thus the German diplomacy towards the Armenian Question had been conducted on both sides of the street, so to speak. With tacit British approval, German Foreign Minister von Richthofen had labored hard in the Rome Conference to secure a settlement that would be least subversive of Ottoman sovereignty as possible, while still securing protections for the Armenian minority to settle down public opinion back home. At the same time he had used the legendary Johannes Lepsius, who had made the situation of Armenians widely known in Germany a decade earlier to open unofficial contacts to the Armenian leaders. This way von Richthofen both hoped to win them over to a compromise, while maintaining the goodwill of the new Ottoman regime in the eventuality of a breakdown of negotiations.

The German activities in Rome Conference had alarmed the Russian leadership a great deal. They remembered well how von Bismarck had presented himself as a "honest broker", and then created a European coalition of other Powers to enforce the Treaty of Berlin, putting the Balkans on ice despite the stunning Russian victories over the Ottomans. Since then Russia had sought to prolong the backwardness and isolation of the eastern Anatolian lands as a defensive buffer covering the recently conquered and volatile Transcaucasus. In addition the Russian generals and diplomats had hoped that the lack of good infrastructure would also act as a barrier to foreign competition in Persia, a land that many Russian leaders viewed as a key to the future economic penetration of the Levant. But the Germans had declined to conclude formal agreements with Russia regarding future spheres of interest in the region. They had merely persuaded the Ottoman regime to direct the route of the new Anatolian Railway southwards, away from the Russian frontiers and the Black Sea coast. Ambassador Zinoviev had then quickly obtained the Sultan’s agreement not to grant further railway construction concessions to foreign powers north of a line between Kaiseri, Diarbekir, Sivas and Kharput. This attitude was still present in the contents of the new Russian proposal that they brought forth as a solution in the Rome Conference. The new reform project had been prepared by André Mandelstam, the dragoman (translator) at the Russian Embassy in Constantinople in cooperation with Nubar Pasha and other representatives from the Armenian National Assembly. Ivan Zanriev, a Dashnak leader with good connection in ruling circles in St. Petersburg had also played a decisive role in expressing Armenian views and hopes to the Russians. Mandelstam himself was a protégé of Fedor Martens, the leading Russian scholar of international law, and a close colleague of Boris Nolde, head of the Legal Advisory Office in the Russian Foreign Ministry. Thus the proposal was in essence a legally impressive and carefully crafted Armenian reform wishlist mixed together with a plan that aimed to secure Russian geopolitical goals in the region.

The contents of the August Ultimatum were developed in close cooperation with Boghos Nubar Pasha and his colleagues.

Armenian language was to be given legal position in education and local administration, special commissions would be organized to examine local cases of land confiscation with the power to expel recently established Muslim refugee groups when necessary. The Hamidiye irregular cavalry regiments were to be disbanded. Previously designated six Armenian vilayets (Bitlis, Diarbekir, Erzerum, Mamuret-el-Aziz, Sivas, and Van) were to be united together to form a single province, administered by jandarma commanded by European officers and led by either an Ottoman Christian or a European governor general supported by local advisory council with representatives of all local religious groups. This official would be appointed by the European powers for the next five years to oversee matters related to Armenian issues. Finally the treaty would obligate the Powers to enforce the implementation of the reforms.

Before it was officially represented to the conference at Rome, the project was introduced and discussed at a private meeting of the French, British and Italian ambassadors. The Russian representatives emphasized the fact that their government sought to avoid any measures that might antagonize the Ottomans. Count Muraviev himself truly believed that pressing the reform project too harshly might provoke the Ottoman regime or the local population to desperate measures. He tried to convince the other Powers in Rome that Russia had too many internal troubles with her current Armenians to contemplate further annexations of Ottoman territory in Anatolia.[3] But while the representatives of other Powers came to recognize the sincerity of Russian statements that they contemplated no territorial expansion, they still pointed out that the Mandelstam Plan would still lead inevitably to that outcome. The Russians were quick to answer that in a case that the Mandelstam Plan would not be adopted, the region would descend into a civil war, thus forcing the Russians to conduct a military intervention. Thus the Russian diplomats indirectly and quite bluntly implied that that without her plan partition would result. The German delegation asserted that partition would result directly from the plan itself. British diplomats agreed that the Mandelstam Plan looked too much like the beginning of partition to be allowed - the cure was worse than the disease, and British policymakers were worried on the possible effects the partition of Ottoman Empire would have on their Indian Muslim subjects. The Ottoman government was terrified to find out the content of the original draft via diplomatic leaks and trusted informants, and sought vigorously to alter it, seeking to play the mutual distrust and disagreements of the Powers against one another. The Ottoman leaders knew that they held one trump card: the general desire of the Powers was that the Ottoman Empire would - at least for now - survive intact as a political entity. They also drafted their own counter-proposal that was centered around the idea of a network of inspector-generals.

Ultimately the German strong opposition to original Russian draft succeeded in obtaining several important modifications, such as the division of the region into two provinces headed by inspector-generals, who still would (to the dismay of the Ottoman government) have the authority to appoint and relieve relieve provincial officials and bureaucrats as they saw fit. They would be posted in Van and Erzerum. The counterproposal was largely agreed, and St. Petersburg merely instructed Russian diplomats to insist on three points: The 50-50 principle of local leadership be applied to vilayet of Erzerum, that Muhacir (Muslim refugees from Balkans and Caucasus) would be prohibited from entering the territory of Armenian Vilayet and that local Christians would be guaranteed a place on the general councils in Harput, Dyarbekir and Sivas. Just like in Macedonia, the actual situation in the area ensured that the new administration would face an impossible task in trying to define "just" ethnic and religious borders and administrative divisions.

The main problem of Armenians and non-Armenian Christian minority groups in Ottoman Empire in 1905 were their geographical divergence - they were a sizeable minority in a lot of places, but a majority in only a few areas. The Nestorian Christians were even more diverse lot than Armenians. Some of them were urban city-dwellers, while others existed in feudal agrarian settings in tribal mountaineer societies like the Nestorians of Hakkari Mountains.The total population of Oriental churches in Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia in the regions of Diyarbekir, Van, Bitlis, Urfa, Der Zor, Mosul and Urmia numbers roughly ~600 000 people, with Nestorians being the largest church with just under 200 000 members:

Assyro-Chaldeans (East Syriac): 190 000

Assyro-Chaldeans (West Syriac): 133 000

Chaldean Church (Uniate church with Roman Catcholic Church from 1681): 100 000

Syriac Catholic: 5,600

Armenian Catholic: 12,500

Syriacs in northern parts of Van, Bitlis-Sivas, Harput: 56 000

This statistic excludes the Aramean populations in the greater part of Syria, Lebanon and Palestine.

1. Mehmed Ferid Pasha and Ahmed Issed Pasha:https://www.alternatehistory.com/discussion/showpost.php?p=10037899&postcount=171

2. In OTL the unrest had a lot to do with the general restlessness of Russian society in 1905. But Caucasus was a hotbed of ethnic violence and terrorism already before the Russo-Japanese War.

3. After Manchuria, it is not surprising that other Powers have little trust on Russian statements regarding their territorial ambitions. But ironically this time Muraviev truly means what he says. In OTL Russian government consistently maintained the view that Ottoman regime would retain formal sovereignty over Armenian vilayets up to the early years of WW1! Basic Principles for the Future Ordering of Armenia, published in 1915: “the formation of an autonomous Armenia under the sovereignty of the Sultan and under the tripartite protectorate of Russia, France and England would be the natural result of the longstanding favorable attitude not only of Russia, but of its Allies as well, toward the Turkish Armenians.”

Last edited:

Here's the index page for new readers:

https://www.alternatehistory.com/discussion/showpost.php?p=9891464&postcount=166

https://www.alternatehistory.com/discussion/showpost.php?p=9891464&postcount=166

Just the same year, but in April, France had threatened to withdraw their ambassadors if France wouldn't get a railway concession in exchange for a large loan.

I do not know how that influence the French stance. They were used to drastic measures against the Porte but had already just months ago come to a conclusion of a situation of tension. Most likely the cautious attitude described here is plausible but it might be so that French press further railroad concessions again soon.

edit, another interesting tidbit is that with Pichon at the rudder a bit earlier we might see some strange things happen between Germany and France. The French ambassador to Berlin, Jules Cambon who IOTL seated the post in 1907, was a friend of Pichon, and a supporter of an entete with Germany. I do know close to nothing about Georges Paul Louis Bihourd, the current ambassador, and he would likely remain in Berlin until 1907. But it is an interesting little fact. see: "Jules Cambon and Franco-German Détente, 1907-1914" for some reading.

edit 2: From the Poincaré biography. The focus of the chapter is around the Briand ministry

Source: "The Origin of the French Mandate in Syria and Lebanon: The Railroad Question, 1901-1914"The method by which this pressure was to be applied emerged in a Foreign Ministry note of i June 1904. It suggested that Delcasse prevent the floating of a loan of 2.5 million Turkish pounds 'until the Ottoman Government has dis interested itself in the Damascus-Hama company either by granting a kilometric guarantee to the Damascus-Muzeirib line or, a preferable solution, by authorizing the construction of a junction from Hama to Aleppo, the natural terminal point for our Syrian network'.3 The loan negotiations dragged on for nearly a year, with France attaching very stiff conditions concerning the Syrian railways. The debate waxed acrimonious, and France even broke off negotiations,

threatening a recall of her Ambassador. The tactic worked, for in April 1905 Turkey granted the concession for an extension of the Damascus-Hama line to Aleppo with a kilometric guarantee of 13,667 francs. The Porte also agreed to an indemnity of 3-5 million francs to the Damascus-Muzeirib line for losses it had suffered as a result of the Hijaz parallelism. The tactic of attaching unpleasant concessions to the granting of a loan was nothing new in international relations. But in this case the Quai d'Orsay had intervened and applied this strategy to the Syrian railroads with very satisfactory results. The Foreign Ministry was to use this method again in I913 and I914 with even more spectacular consequences.

I do not know how that influence the French stance. They were used to drastic measures against the Porte but had already just months ago come to a conclusion of a situation of tension. Most likely the cautious attitude described here is plausible but it might be so that French press further railroad concessions again soon.

edit, another interesting tidbit is that with Pichon at the rudder a bit earlier we might see some strange things happen between Germany and France. The French ambassador to Berlin, Jules Cambon who IOTL seated the post in 1907, was a friend of Pichon, and a supporter of an entete with Germany. I do know close to nothing about Georges Paul Louis Bihourd, the current ambassador, and he would likely remain in Berlin until 1907. But it is an interesting little fact. see: "Jules Cambon and Franco-German Détente, 1907-1914" for some reading.

edit 2: From the Poincaré biography. The focus of the chapter is around the Briand ministry

Source: Raymond Poincaré by J. F. V. Keiger page 156Poincare and Barthou, the 'boy wonders' of politics in the 1890s, though 'young crocodiles' for Jules Cambon, were both members of the Comite de l'Orient, and could be expected to maintain the prominence of foreign affairs in the new cabinet. They agreed on the appointment of the former ex-president of the Comite de l'Orient, Stephen Pichon, as foreign minister. It was hoped that he would be able to arrest the decline of France's presence in the Levant, undermined by developments in the Balkans and the risk that the Ottoman Empire would disintegrate. Because the First World War began in Europe, hindsight has led us to believe that before its outbreak politicians' minds were solely fixed on the European arena. In reality France was as much concerned with the Levant, and the 'Syrian' strategy cut across her traditional alliances, giving her more in common with Germany than Russia over a number of issues.

Last edited:

excellent quote

Most interesting. I was aware that French and German authorities held negotiations about railroads and spheres of interest in the Ottoman Empire in early 1914 in OTL, and the fact that France used her financial clout as a leverage throughout eastern Europe (including the direction of the railway construction of her Russian allies), so it is only logical that they pursued this line in Ottoman realms earlier as well. Right now the situation in the Ottoman Empire steals away most of the thunder of the OTL 1st Moroccan Crisis, so French caution here is linked to their desire to maintain as much of the earlier status quo as possible. Their financial sector has so large investments in the Ottoman debts that a default or outright disintegration would be a disaster...(As a sidenote Balkan debts to central European banks seem to be a recurring theme in history

And the Pichon-Cambon contact is another keen observation from your part. French foreign policy is on a crossroads in 1905, and their leaders are still undecided on which path to follow.

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Share: