------------------

Part 17: Night

Palace of Moctezuma II

Midnight of September 14, 1536

Not for the first time in this long, starless night, Cuauhtémoc found himself in his studies rather than his bedroom, poring over documents and reports he had already read several times before, then putting both hands on his head in silent despair. He just couldn't have even a light, uneasy sleep like the one most people in Tenochtitlan (and inside the very palace he was in) were having right now, not when the responsibility for the chaos engulfing the entire Valley of Anahuac rested almost completely on his head. This was no time to blame himself or anyone else for the current conundrum - he had done plenty of that during the retreat from Guayangareo (why did it take Matlatzincatzin so damn long to show up?) - no, he had to continue to plan on how to repel the Purépecha, no matter how many times he and Tlacotzin discussed with the generals before the sun set. The 39 year old monarch and his allies already had a strategy in mind: while the invaders' army was mighty, cutting off Tenochtitlan from the rest of the world would still be a massive undertaking of logistics and organization, one so complicated they would have no choice but to focus their efforts in a single area.

That area, the Mexica high command concluded, couldn't be any other than Chapultepec, whose springs provided most of the fresh water the Tenochca people depended on, and so a large contingent of warriors would be sent there to strengthen its already considerable defenses tomorrow. Still, there were dozens of other variables to consider, namely how the other cities in the valley would behave in the next few weeks or months, and given how Texcoco opened its gates to the enemy at the first opportunity, the prospects of all other altepeme staying loyal weren't good. Something needed to be done to keep them from slipping away, and fast. The growing weight of fatigue was replaced by a sudden tide of ideas in his head, and so Cuauhtémoc got up from his chair, grabbed the nearest blank sheet of paper he could find, and began to write everything down as best as he could under the dim candlelight. He hoped Coyolxauhqui and her brothers (1) weren't poisoning his mind, because some of the thoughts he put into the paper were against everything the Triple Alliance once stood for. Not that that mattered anymore, since said alliance had just ceased to exist yesterday.

When an aide found him, hours later, he was sleeping on his desk, his hand still holding a quill, face planted on the document he spent the whole night writing or, more accurately, scribbling. Hopefully he didn't drool all over it, the aide thought before extending his arm to stir the tlatoani awake.

------------------

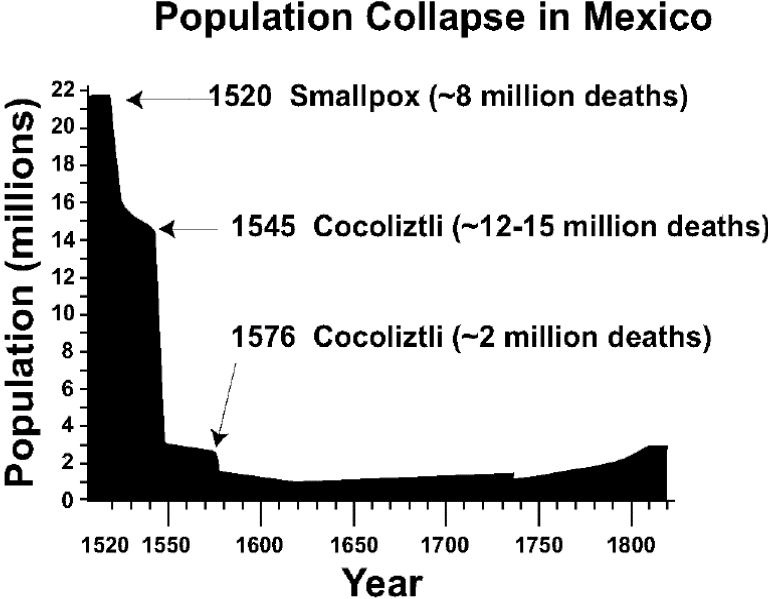

Far from an ordinary siege, the sequence of military actions made in the Valley of Anahuac from mid September 1536 onward would be best described as an all out campaign, dominated by pitched battles fought all over the shores of lakes Texcoco, Xochimilco and Chalco, with the offensive against Tenochtitlan itself being only the final stage. The city in question was both blessed and cursed by its geography: as an island in the middle of a lake, Tenochtitlan could only be attacked through the causeways that linked it to the mainland, allowing the defenders to set up strongpoints and kill zones. They also had a powerful lacustrine fleet of 50 brigantines (all following the design made by Martín López in 1523) and hundreds of war canoes, which meant they could send troops anywhere along the shore, be it for sorties or to reinforce strategic positions. Many (but not all) of the brigantines also had cannons, the very weapons that saved the Mexica from annihilation at the Battle of Guayangareo. The Purépecha had no means to take control of the lakes from this wall of wood, making their objective far more difficult to achieve.

However, Tenochtitlan had two Achilles' heels: its population was so large its food supply depended not only on the many chinampas around it, but also the fertile farmlands in lakes Xochimilco and Chalco, which were controlled by altepeme that could easily defect, just like Texcoco did. Worse still, nearly all its fresh water came from the mainland, transported from Chapultepec by the homonymous aqueduct - if it were cut, thousands of people would die of thirst within days.

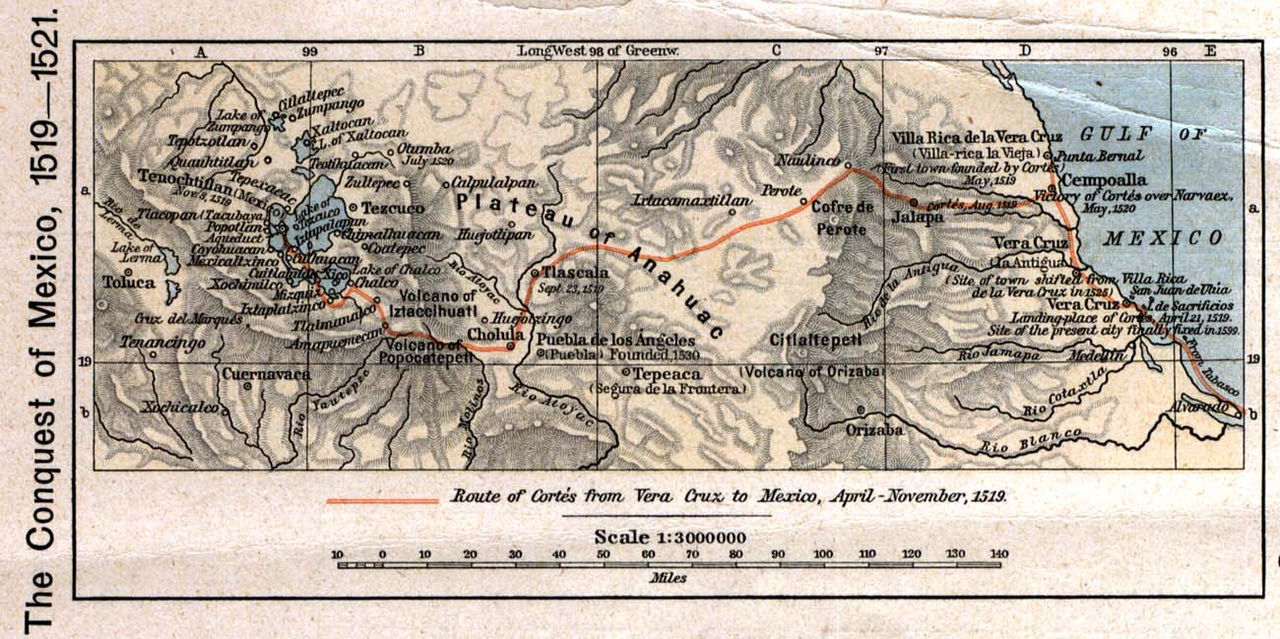

The Valley of Anahuac in the mid 16th century. The Mexica headquarters were located at Tenochtitlan (obviously) and the Purépecha at Texcoco.

Unsurprisingly, Chapultepec became the site of the siege's first major clash, on September 15. Unfortunately for the attackers, the Mexica authorities recognized the hill's importance for decades, and after the arrival of the first Europeans, they built a large fortress there with the assistance of Spanish engineers, one whose defenses were continually strengthened since the 1520s. This fortress, the first version of the Castle of Chapultepec, was a mighty obstacle to any attacker, and its garrison had just been reinforced the day prior. With no means to bring down its walls, the Purépecha tried to scale them with ladders instead, and were repulsed with ease. But while the Mexica drew first blood, they had only so many troops to spare (around 65.000 men, when the Tenochca garrison, Matlatzincatzin's army and the survivors of Guayangareo are all added together). Because of this, they couldn't strengthen their defenses in one spot without neglecting them elsewhere.

One such place was the city of Chalco, which was extremely vulnerable to an attack given its relative proximity to Texcoco, which the Purépecha chose as their headquarters. But rather than use brute force and thus risk alienating other cities in the Valley of Anahuac, the besiegers turned to subterfuge, making moves that indicated they were preparing to launch a second attack against Chapultepec. The soldiers sent in this deception carried many more torches than they needed, and thus, when they made camp near the castle and lit them during the night, it seemed the bulk of the Purépecha army was about to make a major assault. When they suddenly marched against Chalco on September 19, it was too late for Tenochtitlan to help its garrison, which was so outnumbered they chose to evacuate without a fight, but not before looting or destroying as many food depots as they could to keep them from falling on enemy hands. Although this was a sound move from a military perspective, it outraged the Chalcoans and gave Tangaxuan and Ixtlilxochitl yet another event with which they could frame themselves as liberators.

But more than a propaganda coup, the fall of Chalco strengthened the besiegers' southern flank, and gave them a shot at marching into the Iztapalapa Peninsula (one of the main entryways into Tenochtitlan) without the risk of being cut off from their headquarters. A detachment led by Cristóbal de Olid did exactly that, capturing Ixtapaluca on September 22, but they were met and checked by a Mexica force of roughly equal size and forced to fall back before their advance could acquire any more momentum. Even so, Ixtlilxochitl convinced the nobles of Chimalhuacan, just to the north of Olid's position, to switch sides, leaving the peninsula wide open for attack.

Despite this, Tangaxuan didn't order the Purépecha army to press on its advantage there, but instead commanded it to prepare another attack against Chapultepec, and this time for real. Thousands of warriors were sent against its walls in an all out assault (a far larger effort than the one made when the siege began), scaling them with ladders and engaging in brutal hand to hand combat with the garrison. The result, however, wasn't just a defeat for the besiegers, but a disaster: the Mexica defenders were well rested and ready, their ranks constantly refreshed and cycled with new arrivals from Tenochtitlan, and many of the Purépecha troops were blasted away by cannon fire from nearby brigantines before they could even climb their ladders. The scale of their loss was such that the garrison, together with the crews of many lacustrine vessels, launched a sortie that drove their enemies from the castle's surroundings.

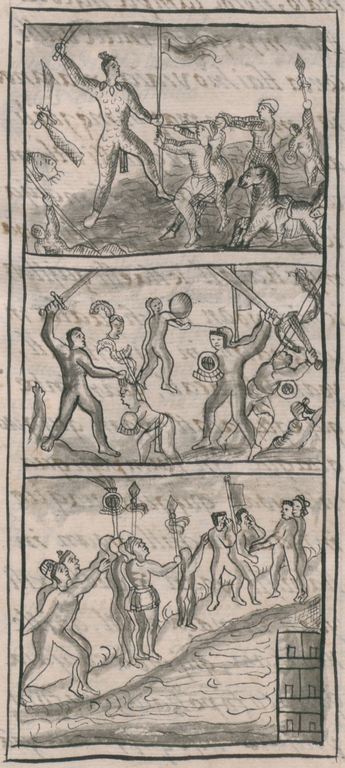

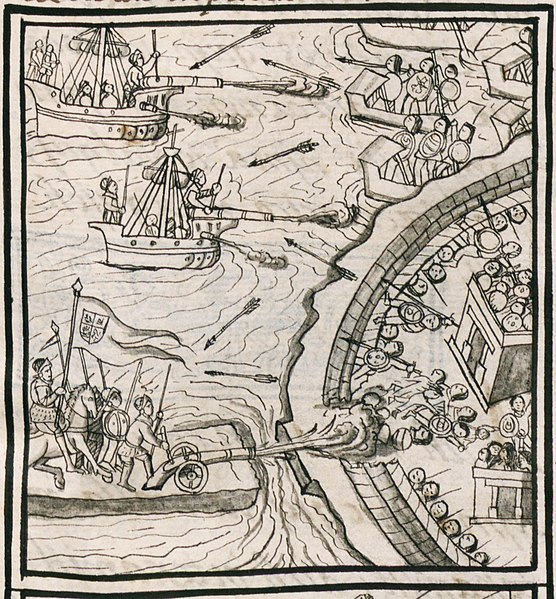

A codex showing the crucial role Mexica cannons played in defeating the second attack against Chapultepec.

Still, even a defeat as calamitous as this was, ultimately, of great use to the besiegers: it showed them that attacking Chapultepec was not worth it, because even if they took it their forces would suffer so many casualties it would likely be impossible for them to deliver the coup de grâce needed to bring Tenochtitlan to its knees. Meanwhile, Cuauhtémoc and his commanders were hesitant to leave the protection of their fortresses and risk their last remaining troops in a field battle - had they done so and won, the siege would've ended right then and there. As it was, both sides stayed put as September gave way to October, the Purépecha waiting for reinforcements from their homeland and the various cities that now pledged allegiance to them, and the Mexica entrenched themselves as much as they could in the areas of the Iztapalapa Peninsula still under their control, especially the Star's Hill, where the New Fire Ceremony was performed every 52 years, granting it enormous religious significance.

During this lull, banners bearing the symbols of the Triple Alliance began to appear in growing numbers in the southern part of the valley, slowly approaching Tenochtitlan (2). The streets of the metropolis burst into celebration at this news, which was only strengthened by reports that the Purépecha did not try to intercept the new arrivals, a sign they were surely the vanguard of a mighty relief army. Cuauhtémoc received the warriors personally in Tlacopan, and it was only then that he and the rest of the Tenochcas realized how wrong they were: these men weren't part of a relief force, but the shattered, exhausted remnants of various garrisons whose cities rose up against Mexica authority throughout the entire empire.

Most of them came from the far south, as Cocijopij took advantage of his overlord's troubles to launch his long awaited rebellion and take over most of the

Huaxyacac Valley in a matter of weeks. Others brought ominous reports of Spanish activity in the east coast, no doubt Núñez Vela mustering his forces to avenge his diplomatic defeat months earlier, and thus even cities like Cholula, whose population didn't rebel (probably out of gratitude for their homeland's reconstruction in the previous decade), couldn't afford to send anything more than symbolic gestures of support. Far from a morale boost, the new warriors were little more than extra mouths to feed, and the exact reason why Tangaxuan and his allies did not try to stop them from reaching Tenochtitlan is still a mystery - they were most likely aware they weren't worth the effort.

The lull ended on October 8. That day, the Purépecha tried to pull the same gambit that gave them control of Chalco, a feint in one direction followed by a real push elsewhere. They made some threatening moves near the Star's Hill a few days prior, while deploying the bulk of their forces against Xochimilco in a move whose objective was to deny the Mexica any access to the southern farmlands, forcing them to either fight a decisive battle or slowly starve. But the besiegers sent, a day prior to their assault, a message urging the altepetl's notables to rebel as soon as they attacked, lest the local garrison loot or destroy their food supply like what happened at Chalco. The letter was intercepted by either a member of that same garrison or a local noble, who promptly sent it to Tenochtitlan. Thus, the Purépecha were met by the brigantines whose cannons had become the bane of their existence by this point, and their attack was repulsed with heavy casualties.

But unlike the aftermath of what became known as the Battle of Chapultepec, this time Cuauhtémoc was not satisfied with sitting inside his capital's defenses while the enemy licked their wounds - he wanted to follow this latest victory up with a decisive battle. Keeping tens of thousands of warriors and hundreds of thousands of civilians in the capital and the surrounding area safe from hunger and thirst had become a nigh impossible task, and the close quarters in which they were forced to live were fertile ground for epidemics.

Worst of all was the fact the Mexica forces' gunpowder reserves dwindled with every engagement, so their vaunted cannons would become useless if he didn't attack soon. The day after the clash at Xochimilco, he rallied all the men he could muster without emptying the various garrisons scattered throughout the valley (around 50.000 troops) and marched down the Iztapalapa Peninsula in a beeline towards the Purépecha headquarters at Texcoco. The besiegers panicked, since most of their forces were still in the south - even if they did catch up, there was a good chance Texcoco would already be a pile of rubble by then. But the renegade city' garrison revealed a new weapon, one the Mexica had never seen before despite everything they went through in the last decade and half.

Trebuchets.

The trebuchets used in the Siege of Tenochtitlan were probably similar to this French replica.

Long outdated by European standards, these massive wooden beasts were built on the initiative of Cristóbal de Olid in an attempt to compensate for the Purépecha army's lack of artillery, which was sorely felt since the siege began. However, he and the other few dozen Spaniards in Tangaxuan's service (all survivors of the shipwreck that made him and his court aware of the power of steel armor and firearms) had about as much experience in engineering as Martín López had in shipbuilding when he designed the first Mexica brigantines, and as a result there was no guarantee they would work (3). They did, much to the besiegers' relief, and Cuauhtémoc's army was met with a hail of giant stones (some weighing as much as 300 kilograms) once they got within range. Some stones were even covered with wood or a flammable fluid and set alight, making them look like meteors that crushed and scorched several hundred men. The sight was so terrifying the tlatoani ordered his forces to halt and better assess the situation, before they broke and ran.

By the time the Mexica scouts reported Texcoco was almost defenseless, the main Purépecha army under Tangaxuan was in its way to relieve it, and Cuauhtémoc, outnumbered, was in no mood to risk a second Guayangareo by trapping himself between them and the trebuchets. He ordered a retreat, but by then it was too late to avoid a pitched battle, and even though his force made it out in one piece, which was especially impressive given the odds were against them, morale among the Mexica plummeted once they returned to Tenochtitlan, their great attack over with a bloody draw. Worse still, they were almost out of gunpowder, having spent it to fight their way back to the capital.

With their enemy at their weakest point so far, the Purépecha marched against Xochimilco once more on October 12, and this time the city struck its colors without a fight. Tenochtitlan was now deprived of the majority of its food supply, and the besiegers pressed their advantage by attacking the Star's Hill two days later - but even despite their growing numerical advantage and their new siege engines, it took them a full day of fighting comparable to the Battle of Chapultepec for them to capture it. Still, they accomplished their objective, and the path into the heart of the Venice of the New World was now open. But rather than attack immediately, and thus allow the Mexica to concentrate their resources to fight against a single thrust, the Purépecha set up their trebuchets on top of the hill and began a lengthy bombardment of the great city below.

They sought another way in, to launch a two or perhaps even three-pronged assault. While Tlacopan, governed by Tetlepanquetzal and entrypoint to another causeway, resisted the Purépecha advance so fanatically they were forced to withdraw for the time being, Tepeyacac, located just a few kilometers to the north, did not, capitulating on October 19. The time for the final blow had come.

Various scenes of the siege, the last of which is the attack into Tenochtitlan itself.

On October 25, 1536, the Purépecha and their various allies launched their two-pronged assault against Tenochtitlan, marching over the Iztapalapa and Tepeyacac causeways. Outnumbering their opposition by almost two to one at this point, their plan was to overwhelm the Mexica by forcing them to fight on two fronts, storm the city and wrap up their victory by looting it to their heart's content. The northern force was led by Tangaxuan, while the southern one (which was expected to face tougher resistance and so was slightly larger) was led by Cristóbal de Olid and Ixtlilxochitl II. Hours before the attack began, Cuauhtémoc ordered the metropolis' arsenal to be opened up to the civilian population in a desperate final measure to bolster the hungry, tired and despondent forces he had available.

Every street and building was contested, the fighting becoming so desperate and brutal most Mexica warriors killed most of their opponents instead of worrying about capturing them for future sacrifices - the streets were so slick with blood the gods probably wouldn't need them for years to come. Those too old, young or infirm to fight built barricades from whatever materials they could find, and those who could but had no weapons used pots, kitchen utensils and other random objects they could get their hands on to fight the invaders with suicidal bravery, boosted by apocalyptic despair. Every inch of ground cost a liter of blood and sweat, but even so the Purépecha expanded their zone of control ever further into Tenochtitlan, street by street, building by building.

Finally, late in the afternoon, Tangaxuan's men made a major breakthrough in the northern sector: they reached the Great Market of Tlatelolco, and went into a frenzy upon noticing the plaza was full of valuable goods left behind by the merchants who set up shop there in normal circumstances. Thousands more poured in despite the irecha's attempts to maintain order, looting everything not nailed down. It was at this moment, when the thousands of well trained Purépecha warriors were little more than a well armed mob, that the Mexica struck. Cannons hidden in strategic positions opened fire on the plaza, tearing the compact mass of men to shreds at the cost of their last remaining reserves of gunpowder. The infantry moved in right after, and the panic that engulfed the Purépecha was so complete that their desperate attempt to fall back devolved into a stampede.

Tangaxuan had no choice but to order a retreat back to the mainland, just as Olid's forces were about to break into the Sacred Precinct, the walled complex housing the Great Temple. With the northern districts safe for now, Cuauhtémoc ordered all forces to mobilize to its defense, and they were just barely able to push them back before the sun set. The Mexica could not, however, kick them out of the city entirely - as both sides put down their weapons and got what little sleep they could during the night, many of the southern districts were still under the invaders' control.

When the sun rose on October 26, everyone in Tenochtitlan, warriors and civilians alike, knew the fighting wouldn't last a day longer. An oppressive silence reigned in the air, even as the fires that broke out the previous day continued to fester and devour more and more buildings with each passing minute. Olid and Ixtlilxochitl prepared to attack the Sacred Precinct a second time, while Tangaxuan's men rallied after the bloodbath at Tlatelolco and were now massing at Tepeyacac, ready to cross its causeway once more. Cuauhtémoc and the rest of the Mexica high command had a plan, on paper: kick the enemies in front of them out of the city, then turn north and hope for the best. In truth, they all knew this would be their final stand, one last hurrah before they and their home joined the ashes of history.

Finally, after what felt like an eternity, they charged. The Purépecha met them in kind, and the silence was replaced by a crescendo of weapons, shields and armor clashing against one another, their sickening song broken only by the screams of the wounded and the dying. And yet, despite everything, neither side budged - they were all too tired to push the front line more than a few meters here and there. An outside intervention was required, and everyone knew where it would come from. And yet it never came, because Tangaxuan's forces, far from crossing the Tepeyacac causeway, were instead marching westward, back to their homeland - they were retreating. As they did so, the reason for their decision revealed itself: thousands, no, tens of thousands of warriors approaching Tenochtitlan from the east, their flags bearing the symbols of the Triple Alliance and Tlaxcala.

Relief had finally arrived, and from a nation that, while now a part of their empire, had still been one of their most bitter enemies for generations. The Purépecha panicked and raced for the Iztapalapa causeway before they were trapped, and while many made it out - the Tenochcas were too tired to pursue - Olid and Ixtlilxochitl were not among them. The latter's fate is unknown, the most famous version of it stating he was hit on the head by a brick thrown by a nearby civilian, then trampled to death by his men. Olid's demise, meanwhile, is unanimous among all sources, the only divergences being minor details: he was captured by the Tlaxcaltecs, led by Xicotencatl II, and brought before Cuauhtémoc, who, rather than order the Spaniard to be sacrificed with the other prisoners (as was custom), grabbed a macuahuitl and beheaded him on the spot.

The capture of Cristóbal de Olid. He probably looked a fair bit older in real life.

This act shocked Xicotencatl at first, but once he became fully aware of the amount of blood spilled not only in Tenochtitlan's streets, but the entire Valley of Anahuac, he and his overlord agreed that no ceremony, however grand or extravagant, could come close to the sacrifices made here. After forty-four days and at least sixty thousand deaths (most from starvation and disease), the Siege of Tenochtitlan finally came to an end. And yet, the scale of the carnage and suffering would not only be matched, but surpassed by the changes to come.

The Nepantla period was about to enter its most dramatic phase.

------------------

Notes:

(1) The Moon and the stars, who are the main antagonists of Aztec/Mexica mythology. They want to destroy the world, and only Huitzilopochtli (with the help of lots and lots of human blood) can stop them... which is a very convenient excuse to wage war almost nonstop, so as to get new prisoners to sacrifice.

(2) Remember that Texcoco has just defected, so it'll take a while for the various flags and other symbols associated with the empire (which feature its glyph) to change.

(3) Fun fact, according to what I found Cortés and his men built a trebuchet when they besieged Tenochtitlan IOTL. It fired only a single stone, because said stone went straight up and destroyed it when it came back down.