Chapter XVIII - Postbellum

Not long after the ink dried on the Treaty of Sévres, Europe settled in for a new period of peace. The horrors of industrial scale warfare prompted the Eurasian War a new nickname: the Last War.

The Russian Empire

The Czar attending a memorial service for fallen soldiers and honoring veterans

Ecstasy could not even begin to describe the signing of the peace in Russia. Their ancient enemies destroyed, their ancient rivals humbled and Constantinople restored to Orthodox Christianity. The immense loss of life however ingrained itself deep into the Russian psyche. Maimed soldiers were seen begging on the street in every city and there was little the state could do to alleviate their suffering. The war put tremendous strain on the Russian economy, and it was decided that modernization and industrialization must continue. Soldiers, now returning to the fields and factories however could wield considerable influence, more so than before, leading to a significant improvement in working conditions. This was mostly due to fear of another uprising akin to 1905, but now with a considerable number of veterans among workers. Russia in 1917 was still mainly an agricultural state, and the road was long yet still. In 1920, the health of the Czarevich's health took a turn for the worse, and Nicholas started to distance himself from politics, more so than ever, leading to the Duma gaining more control of the affairs of the state, even signing some of this powers away in 1922, leading the way to Russia becoming more and more a constitutional monarchy. The lessons of the war were also learnt, and STAVKA ordered research into new artillery, paving the way for new Russian doctrines based around the successful rapid artillery barrages during the Brusilov Offensive. While armored cars were used with some success in the Far East, Russia instead decided to rely on artillery (and later, anti-armor artillery) for large scale offensives. The new territories in Anatolia were swiftly incorporated into the Greater Armenian Autonomous Oblast, which guaranteed Armenians and Greeks considerable self rule, somewhat similar to Finland and Poland. Nevertheless, most Greeks in Trebizond instead chose to leave for the home country, as invited by the Greek government. In their place, Russian settlers were urged to move to the area, along with the many Armenians that were now fleeing from other parts of Anatolia, the Middle-East and Persia. The new Oblast would be a tumultuous place for the coming decades, but as housing projects, new industry and railway was brought into the area in the early 1930s, things have settled down.

Great Britain

London in the early 20's

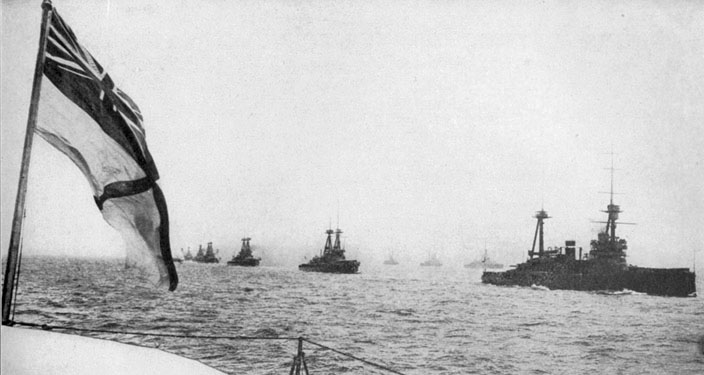

A monumental task now lay before Britain: waking up from the lethargy of defeat, something unseen for a century. As the government resigned after the war, the empire was in shambles. A great many lives were lost, not only British, but Canadian, Australian and Indian. Voices about secession were heard from all three, as Canadian and Australian politicians claimed that their boys have been thrown into the mouth of a beast for nothing. In India, nationalist ideas began to gain prominence as veterans returned from the war, ironically the only force that was not subjected to a severe defeat. Something had to be done, before these voices became too loud, and in 1926 a plan was drafted to keep the empire together in a new Commonwealth. The plan outlined a series of changes which included representation of the Dominions in London, as well as a degree of self-governance. The proposal at first included Canada, Australia, India and South Africa, with possibility of other territories gaining representation later, which was mostly tied to development (Malaya and Thailand were proposed to be the next, sometime in the 1950s or 60s). While satisfying most parties on paper, these changes would take decades to take hold, but provided a model for other Great Powers in the future. Britain thus remained the pre-eminent power, although the industrial output was now far outshined by Germany and trailed closely by the United States. A famous group of writers and other artists in London, called the Lost Generation have often noted that the 20th Century will likely be known not after a British, but a German monarch. Some even more pessimists said it might be a Czar. The new Palestinian territories were quickly incorporated into British administration, with the aim of setting up a buffer between Egypt and Russia. While most of the Levant, especially Syria saw a lot of violence during and directly after the war, the Palestine was relatively quickly pacified. London made an effort to get Jews settle in the area, but given the (perceived or real) instability of the region, most Jews that were leaving the former Ottoman Empire instead chose to settle in German Africa, a place with already considerable Jewish population. Nevertheless, some Jews did settle in the city of Tel Aviv, which is to this day the largest Jewish city in the Palestine. Another effect of the war was the resurgence of the ancient rivalry between Britain and France. The French seizure of Libya and their interference in the peace angered many in London, and new plans were drawn up for a possible future war with France. A war, where the Royal navy could finally be put to use. There were however fears that like the Eurasian War, this hypothetical conflict might not be easy. France now controlled all of the Western Mediterranean, with the exception of Gibraltar and Malta, and operating from their many ports (including their access to Spanish and Sicilian ones) they could effectively shut down British incursions into these waters using cheap torpedo boats and submarines, and even endanger Egypt overland. And a large scale battle over the vast African continent was very much undesirable, especially since France had an edge in troop numbers and infrastructure.

Prestige. Gloire. Often repeated words in Paris coffeehouses after the war. France, without fighting a war has won Libya and managed to put their foot in the door in the Levant. While the great prize, Jerusalem has eluded them, Syria proved to be an excellent stepping stone to gain control of the Arab states in the Fertile Crescent. As Syria and Iraq descended into civil war, the Russians were quick to recognize the Kurdish state and support them in the face of a Persian incursion. The Empire however had to be cautious, as Germany also wanted a piece of the cake, and the had boots on the ground to back it up. Eventually, an agreement was reached, known as the Luxemburg Settlement, and Syria was split, the North and East coming under French control based around Aleppo, while the South, including Beirut and Damascus became German imperial holdings. With this, the Kurds were allowed, with French help and Russian arms, to seize the city of Mosul, while the Foreign Legion marched into Tikrit, and the towards Baghdad. Britain strongly protested this move, but could do very little. The public would not accept another war, and a French buffer was still preferable to further Russian expansion. As France surrounded and took Baghdad, the German Ostafrikengeschwader sailed into the Persian Gulf and took Kuwait, along with all the former Ottoman coast, including and up to Bashrah. This completed the division of the Middle East, putting a wedge between Britain and Russia. In the 1920's, France continued to flourish culturally, while also investing in the army and the navy considerably, with the aim of being able to counter Britain in a potential war. While relations were amiable, considerable fortifications were also erected in Alsace-Lorraine to dissuade any German invasion.

The German Empire

Emperor Karl at the funeral

As the Venetian Valentine died down by 1917 under the heavy boots of the Reichsarmee, Germany was ready to flex her muscles in the wake of the Ottoman collapse. Fearful of too large gains of either France, Britain or Russia, Vienna decided to seize as much valuable terrotory as possible. This ended in the division of Syria with France, that was later organized into two new German dominions: Lebanon, based around Beirut, and Damascus. The former was envisioned to be a haven for Christians in the Middle East, and indeed many chose to move there during the civil war, creating a melting pot of various Christian denominations, united mostly by their tacit support for German rule, and fear of Muslim aggression. As France advanced East along the Euphrates, so has Germany, as the Reichsflotte seized Kuwait and German forces moved to take Basrah. Germany was could now be counted among the major colonial powers and was looking at the turn of the decade with hope. However, in October 1918, Kaiser Franz Josef finally died. The man who has lead his nation through the revolutions, the Italian and the unification wars and into the 20th century was now gone. With Franz Ferdinand having been killed in Venice, it was now up to the new Kaiser Karl to fill the shoes of his father. A timid and religious man, he was well liked by the population and eventually prove to be a capable and stern Emperor. In the 1920s, Germany continued its almost unchecked growth, becoming the world's industrial powerhouse. The military was greatly reformed under Karl as well, as a new generation of Prussian officers have risen to prominence in the Reich. The lessons of the Eurasian War were put to good use, in particular the new doctrines based around armor, as observed by Russian successes in Manchuria. While Russia did not trust the flimsy constructions and Britain instead focused on heavy armored vehicles known as tanks that used tracks to overcome obstacles (but were cumbersome in turn), German engineers attempted to combine the two into a fast tracked vehicle with rotating turrets. The man behind these designs was Günther Burstyn with his idea of the Motorgeschütz. His research was given huge funding with the help of Heinz Guderian, and his construction became the core of what would become the German Panzerkorps. Fixed wing aircraft were also developed greatly in the 20s, with German airplane industry coming to dominate the world. As planes became bigger and more reliable, so have Zeppelins become more and more obsolete. Although used extensively well into the 30s and 40s, after the accident of the American blimp Manhattan in London, they have faded greatly. The only place where they remained in extensive use was Africa. Originally, hauling cargo was much easier over the vast distances, which led to their use as such well into the 50s, and after that as a source of leisure. African blimp cruises are still extremely popular today, albeit only affordable to the wealthy. As for Africa, the end of the war had a profound effect on German East Africa. On the one hand, Germany offered many refugees from Europe to settle in the region, hoping to bring expertise that could be used to fuel local industry. While people from the Balkans did not go in great number, Italians and Czechs from the Reich were more inclined to undertake the journey to be provided free land and not be subjected to Germanization. Ironically, since the lingua franca in the colonies was German, they eventually mostly Germanized themselves. Hungary was also a large exporter to these colonies in terms of dissidents. Many Slavs and Romanians were given a choice to move to German Africa or face prosecution and prison. Given how this journey was effectively free as opposed to a long American trip, many decided to go. Another important group to move there was the Jews. Fleeing the wars in the former Ottoman Empire, they were happy to join the other faithful in Ethiopia, where Aksum would virtually become a Jewish city by the mid 20s. The inflow of immigrants contributed to improvements in infrastructure, but was of course not without conflict. The traditional pastoral life of the locals was greatly upset by the settlers, and the unregulated nature of the local economy contributed greatly to their impoverishment. By the end of the decade however, the price of coffee rose enough that the state stepped in, providing funds to modernize the plantations wit modern irrigation, infrastructure and most importantly laws protecting plantation workers as well, most of whom were natives. This improved the quality of life on East Africa greatly, and would become a reference point for other modernization projects across Africa. Today, German East Africa is not only a major provider for coffee and cotton, but also a major tourist destination.

While the defeat and immense losses in Manchuria had been terrible, they haven't made a huge dent in Japanese militarism. In fact, it was seen as the failure of the army, while the navy has defeated the Russians before. The political climate in relation to expansion into China however was seriously affected. The general view now was that a major land war on the continent is to be avoided, and that static defenses were the way to go forward. Thus, the Korean border was fortified to the extreme, becoming the most well fortified area in the world. Russia, while mostly exhausted, was now back, and free to expand their navy in the Pacific: one more reason for the IJN to take the lead into leading the Japanese effort. The 20s were mostly spent with consolidation in Japan. As Korea was properly incorporated, and efforts were made to industrialize the Philippines, Japan was now also reconsidering their ties to Britain. Had it not been Britain that dragged them into an unwinnable war across the trackless wastes of Manchuria and Siberia? However, for now, the alliance with Britain stayed, yet new objectives and plans were drawn. Japan desperately needed resources to fuel her booming industry. And having been thrown out of China, there was one place that was ready for the taking: the wast islands of Dutch Indonesia.

The Republic of China was often seen as a state ready to implode. Yet, as the Beiyang Army marched victoriously across the streets of Beijing, the nation was beginning to show signs of life. Yuan Shikai's regime has never been more popular, nationalist flags were flying high in all major cities. But all was not yet well. Shikai was now becoming increasingly confrontational with the Kuomintang, and some sources indicate that he intended to crown himself emperor riding on the surge of his popularity. What might have happened is up to speculation, as Shikai died in August 1916, leading to new elections, which were won by the Kuomintang by a landslide, placing Sun Yat-Sen into the presidential seat. Although there were fears of the Beiyang army disintegrating in the face of Shikai's death, and some units did disband and join various frontier warlords, most of the army swore allegiance to the Kuomintang, and stayed an intact force. Sun, after his inauguration promised to restore peace to the country, and the newly renamed Republican Army soon embarked on the long Western Expedition, a campaign to restore order to all provinces, lead by General Chiang Kai-Shek. The campaign would be an arduous task, and would only be declared finished in 1928. In the meantime, Sun recognized the need for modernization of the state and declared the "Ten Thousand Steps" program with the aim of industrializing and modernizing China. For this, Sun invited German investors, experts and military staff to train. This move also served to create more formal ties with the German Empire, as Beijing had little trust for either Japan, Russia, Britain or even France, due to their presence in Indochina. A new China was born.