You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Gold Rose: An Edward of Angoulême timeline

- Thread starter material_boy

- Start date

Parliament of 1379

Parliament of 1379

The Parliament of 1379, sometimes known as Buckingham's parliament, was a session of the English parliament held at Westminster Palace from 29 September to 1 November 1379. It was the fourth assembly of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal and the second full parliament of the reign of King Edward V of England.

Background

Edward V succeeded to the throne upon the death of his father, King Edward IV, in 1377. John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, was made lord regent for the new king, who was just 12.

Gaunt was arguably the only figure with the stature to lead a regency government. He was Edward IV's eldest surviving brother and, as duke of Lancaster, he held the greatest landed estate in England besides the crown itself. He was, however, arrogant, domineering, and highly sensitive to encroachments upon his or the crown's authority, and he had made many powerful enemies as a result. He initially refused the regency, believing that he would not be given credit for its successes and would be blamed for its failures. He hoped instead to pursue his own ambitions in Castile, but Queen Joan, with whom he had a strong friendship, ultimately persuaded him to accept Edward IV's settlement of the regency.

Gaunt was forced to make a series of concessions and public apologies to his various enemies in order to secure the regency and stabilize his young nephew's government, but either he harbored no resentment for the political penance he was made to perform or he hid it uncharacteristically well. Gaunt ultimately took control of the government with little controversy and governed with the support of the upper nobility.

The first parliament of the new reign met in early 1378. The brief reign of Edward IV in summer 1377 had seen the renewal of hostilities with France, which included assaults on all English positions on the continent and the first major attack on the English mainland since the 1330s. Shocked by these attacks, the Commons approved a double grant of taxation to finance plans for a major continental offensive. Chroniclers heralded this as an extraordinary demonstration of support for the new boy king, but in reality such heavy taxation was needed to move the war back onto French territory.

The 1378 grant brought royal revenue to a height not seen since the early 1360s. The English thus had a brief window of time in which they could compete with French military spending nearly pound for pound as they sought to launch a major offensive in Brittany, bolster local action in Gascony, and rebuild their defenses along the southern English coast.

War in France

Brittany became the target of English ambition as they planned to retake the initiative in 1378. A major force was to land at Brest and move north to capture a string of ports along the Breton coast, but a poorly-planned attack on Normandy left too few ships to transport the army to Brest and the expedition never materialized. Only a fraction of the army made its way to Brest while the rest was redirected east to attack Saint-Malo.

The English captured Saint-Malo, one of the greatest and most heavily fortified ports in Brittany, after a short, but fierce siege. They soon gained another great fortress-port, as a newly-negotiated alliance with Navarre brought Cherbourg under English control. The Anglo-Navarrese suffered a major setback, though, when Navarre's other Norman possessions quickly fell to the French. England and France ended 1378 in something of a draw, much as they had the previous year.

In spring 1379, the Breton nobility banded together in opposition to the French crown's attempt to annex the duchy and soon rebelled. Their early efforts were focused in the east, where the duchy's principal cities lay and which was most exposed to French attack. In the west, the English maintained a small army at Brest under the command of Thomas of Woodstock, 1st earl of Buckingham.

Buckingham led an expeditionary force to Morlaix and discovered towns and villages open to him along the way. The local population mistakenly believed the English were allies of the Breton nobility and welcomed Buckingham's men as liberators. Buckingham quickly exploited the situation and rolled over western Brittany. By mid summer, the ports of Morlaix and Saint-Pol-de-Léon were garrisoned by Buckingham's men, effectively bringing all of Léon under English control.

The French response to the Breton rebellion was chaotic. The crown was at first belligerent and raised a small army with the intent to invade, but then abruptly called off the attack and attempted to find a diplomatic solution.

In Normandy, Bertrand du Guesclin, constable of France, avoided the rebellion in his native Brittany by volunteering to lead an assault on Cherbourg. Many at the time considered the fortress to be impregnable and Guesclin soon came to the same conclusion. He arrived in the spring with an army of about 1,200, but was slowly bled of men and supplies. Scouting parties were routinely ambushed, leading to the capture of several hostages, including Guesclin's brother and cousin, and the French war camp suffered repeated attacks from English sorties. Gueclin abandoned the effort and returned to Paris in August.

As the French crown was preoccupied with events in northern France, it lost control of the south. Tax riots broke out across Languedoc in the spring. The region had been forced to bear disproportionately high taxes through the 1370s and the latest grant came despite there being no major action against the English in the region. The tax was never collected, though it was not officially canceled, as local administrators simply refused to act for fear of being lynched. The seneschals of the region begged Paris for advice on how to proceed.

The two great lords of the south, the count of Armagnac and the count of Foix, could not fill the leadership vacuum left by the French crown because they were at war with one another. The count of Comminges had died in 1376, leaving his young daughter as his only heiress. Armagnac and Foix had been fighting for control of the girl and her lands ever since.

The English exploited the chaos in southern France just as efficiently as they had the chaos in Britany. The lord lieutenant of Aquitaine brought the local Anglo-Gascon nobility into his administration, secured the approach to Bordeaux, and swept French garrisons out of the Gascon marches. He encountered no practical resistance, exposing the profound weakness of the French crown south of the Loire.

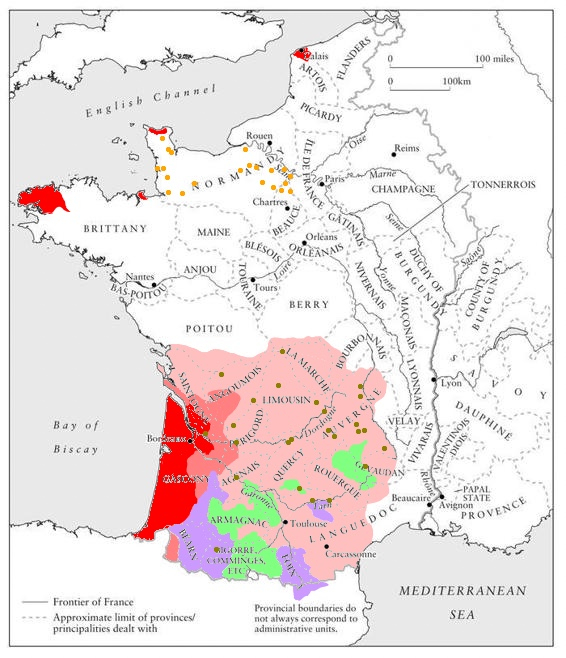

The English in France, 1379

Red: Territories of King Edward V of England

Light red: Gascon marches, controlled by local lords

Very light red: Range of routier company raiding parties

Dark/mustard yellow: Major castles controlled by the routiers

Orange: Norman estates of King Charles II of Navarre, lost 1378

Light green: Territories of Jean II, count of Armagnac

Lavender: Territories of Gaston III, count of Foix

Finances

In early 1378, the government estimated that it needed £200,000 to cover the cost of the planned war effort, but only about £45,000 was expected from ordinary revenue over the course of that year. Even with the double grant of taxation provided by parliament, there was a projected deficit of about £50,000. The Commons believed that better administration of the royal demesne could make up the difference, but this was fanciful. Administrative changes alone could not realistically be expected to more than double ordinary revenue.

Operations in the north of France ran wildly over budget. The cost to supply Brest and pay the wages of its garrison had been estimated at £5,000, but the true cost was closer to £12,000 in 1378 and £10,000 more was needed to resupply the town and finance the earl of Buckingham's campaign in 1379. A new alliance with Navarre brought Cherbourg under English control, an unplanned budget item that cost £10,000 in its first year and another £8,000 in its second. The newly-captured fortress port at Saint-Malo needed not just supplies and wages, but its walls rebuilt following its conquest, bringing costs to more than £20,000 over the course of 1378 and 1379.

The government kept pace with the soaring cost of the war for a time, finding ways to cut spending and raise new revenue. It began by partially offloading defense spending. The country's decentralized coast guard system had worked fairly well at turning back the French attacks on southern England in summer 1377. Now, that system was to be decentralized further. The government leaned on knightly families that had grown rich off the capture and ransom of French prisoners over the course of the war to fortify their lands along the coast. The effort was hugely successful and more licenses to crenellate were issued in 1378 and 1379 than any other two-year period on record.

Defense spending could not be entirely outsourced to the lower nobility, though. In particular, long-neglected fortresses on the Channel Islands required immediate attention. Thousands of pounds were poured into Castle Cornet on Guernsey and Castle Goring on Jersey to build new circuits of walls and fully garrison them for the first time since the early 70s.

As the crown looked to find new sources of revenue, Gaunt stepped in to revive the stalled negotiations for the ransom of Waleran III, count of Saint-Pol. The count had been captured in a skirmish outside Calais in 1374 and the English crown had acquired custody of him soon thereafter. Saint-Pol was one of the great magnates of northern France and so the English expected an enormous sum for his release. Negotiations were complicated, though, by the English insistence that several prisoners of the French crown be released as partial payment toward Saint-Pol's ransom. Saint-Pol had few friends at the French court and the English demands were rejected out of hand. As neither side was prepared to budge, Saint-Pol became stuck. Gaunt, however, dropped demands for a prisoner exchange, cutting the French crown out of the process. Talks for a more straightforward financial transaction soon began and Saint-Pol agreed to a ransom of 150,000 francs (£25,000).

In October 1378, news reached England that the college of cardinals, which was dominated by the French, had declared the election of Pope Urban VI invalid and had instead elected Cardinal Robert de Genève, who took the name Clement VII. The schism in the church was a boon for the English treasury.

Gaunt immediately saw the opportunity the election of a French antipope presented. He had been made to end his public support of religious reformer John Wycliffe in 1377, but he had lost none of his interest in disendowing the church, as Wycliffe preached. As English bishops declared for Urban, Gaunt issued a decree that all the cardinals obedient to Clement were to be deprived of their offices and benefices in England and Aquitaine. He followed it soon after with another decree disendowing all foreign monastic houses, which had been suspected of French collaboration for many decades. The two orders brought thousands of pounds into the treasury and lands worth upwards of £8,000 per annum were added to the royal demesne.

Despite these efforts, the government eventually exhausted its funds, but it found ready creditors among the mercantile classes. Castile had wreaked havoc on English trade and the growth of French naval power posed an even greater threat to trade in the future. English merchants thus took a great interest in the string of royal fortresses that had begun to emerge along the Channel, stretching from Brest to Saint-Malo, the Channel Islands and Cherbourg and then on to Calais. This defensive line promised to protect English shipping and, with it, the wealth of the merchant oligarchy. Tens of thousands of pounds were loaned at low or even no interest to encourage the buildup of these areas.

The government's most generous lenders came from the grocers company and the fishmongers guild, where just four men would loan £10,000 between them, but the merchant class was not alone in lending funds. Thousands of pounds in new loans were negotiated with members of the upper nobility in January 1379 and a £5,000 loan was forced upon the city of London in February.

The government's new forward defensive strategy did coincide with a decline in attacks on shipping in the English Channel and southern coastal towns in 1378 and 1379, but there was a marked increase in attacks on shipping in St. George's Channel and coastal towns in Cornwall, Ireland and Wales. In short, this strategy did not so much end the Castilian and French naval threat as it did shift their targets to less fortified positions in the west. As attacks increased, requests for funds flooded in from Caernarfon, Dublin, and Plymouth. It was clear that the government required new taxation and summons for parliament were issued on 4 July.

Great council

The Lords Spiritual and Temporal gathered at Westminster Palace in early September. The upper nobility had been instrumental to the early success of Gaunt's government. The assembly of a great council in January 1378 had allowed the Lords to set the agenda for the parliament that followed and subsequent great councils had advised the government on the conduct of the war as events unfolded.

On 9 September, Edward V presided as the great council convened in the White Chamber. As had become the norm in the new reign, the young king largely kept his silence through the proceedings and referred all matters and questions to his avuncular regent and the ministers of his government. Edward paid close attention even to formalities, such as the opening prayer and the treasurer's report on finances, to which very few lords cared to listen, as no taxes could be levied in the absence of the Commons. The lords waited impatiently for a report on the situation in Brittany.

Jean IV, duke of Brittany, had sat as earl of Richmond in the three prior great councils of Edward V's reign. The English had supported Jean's claim to Brittany for decades, fighting for his cause in the 1350s and 60s and giving him financial support during his exile in the 70s. The Breton nobility had invited Jean to return to Brittany shortly after launching their rebellion in the spring, but Jean was initially skeptical of their intentions and delayed going until summer. Jean had been back on the continent for more than a month by the time the Lords met. They cheered word of his safe arrival, but there was little other news from the duke.

Buckingham, just 22 years old, then rose to speak of his own time in Brittany. His report made a major impression on the lords. The capture of Morlaix and Saint-Pol-de-Léon, in addition to existing control of Brest and Saint-Malo, gave the English four major ports by which they could enter Brittany. Buckingham drank in the glory, as not even the famed William de Bohun, 1st earl of Northampton, had been able to capture Morlaix during his campaigns in the 1340s.

The success of his first command convinced Buckingham of the superiority of English arms and of his own skill as a commander. He appeared to have little appreciation for the unique circumstances that had allowed him to so rapidly expand the area of English control. He boldly declared that the French were on the back foot and that, with Jean restored to the ducal throne, an English expedition in 1380 could join forces with Brittany and win the war once and for all.

Gaunt brought the Lords back to reality with news from Pamplona. The death of King Enrique II of Castile had saved the kingdom of Navarre from Castilian invasion in 1379, but the new King Juan was determined to pick up where his father had left off. A spring invasion was certain and Navarre had no chance of survival without English support. Buckingham's call for a new expedition to Brittany was overtaken by the situation in Navarre, much to the young earl's frustration. Over the next several days, though, a rush of news from the continent would overwhelm talk of action in either Brittany or Navarre.

First, a flurry of confusing reports poured in from Flanders. The great town of Ghent, which had been simmering with grievances and resentments all through the summer, had finally boiled over into revolt. A local militia known as the White Hoods had lynched the town's bailiff and sacked the residence of Louis II, count of Flanders. The town's council had been removed and replaced with the militia's leaders. The nearby town of Courtrai had already declared its support for the White Hoods and joined Ghent's rebellion against the count.

Then, a squire from Bordeaux arrived with news of the campaign in the Gascon marches. Dozens of enemy positions and great stores of food and supplies had been captured. The Anglo-Gascons had encountered no resistance and earned a small fortune from plunder and patis. The lord lieutenant needed reinforcements to push further into French territory in 1380.

Finally, word came from Brittany. Jean had agreed to a six-month truce with the French and peace talks were set to follow. Anger and confusion followed this last report. The lords had expected Jean to return their decades of support with an alliance against the French.

The lords were overwhelmed by the events in France. Debate as to how they should proceed went in circles, leading to arguments and acrimony. Days ticked by, but there was no consensus to be found as the Commons gathered at Westminster.

In session

The Commons assembled at Westminster Palace in late September. The lower nobility and townsmen had challenged royal government on several occasions in the 1370s, culminating in a dramatic showdown with the Black Prince in the Bad Parliament. The prince's arrest of the speaker of the Commons was a scandal, but the Black Prince was an enormously popular figure, well known for his charm, courtesy, and incredible feats of arms. Gaunt, however, was known for none of these things. He had carefully managed his dealings with the Commons in 1378 to avoid another major showdown, but disagreement in the Lords as to the best path forward had left parliament's agenda wide open in 1379.

On 29 September, Edward V presided as the two houses of parliament met in the Painted Chamber. Simon Sudbury, archbishop of Canterbury, gave a long sermon imploring all those in attendance to work together for the betterment of the realm and the mending of Christendom in a time of schism. William of Wykeham, bishop of Winchester and lord chancellor, then rose to address the parliament as to the reason for their assembly. He recounted the great support that had been shown in the last parliament and detailed the actions that had been taken in the various theaters of war. Then, shocking and horrifying the Commons, Wykeham reported the government's financial position as a result of these actions and called for a second double grant of taxation. Finally, the young king rose to give a short speech in which he formally asked those assembled to offer him their counsel on these matters. The business of the day ended there and a feast was held to celebrate Michaelmas, which was organized at the suggestion of the king.

Plan of attack

On 30 September, the Lords returned to the White Chamber to devise a plan of attack. It appeared France was on the precipice—Brittany had rebelled and almost completely evicted the French, Neville had found no resistance in the Gascon marches, and now Ghent was in revolt. The lords began to share Buckingham's belief that they could bring the war to a close with another major offensive.

Two camps emerged. The first supported a northern strategy. England now held several positions along the northern coast of France from which they could launch an attack, Jean IV remained a possible ally if his negotiations with the French fell through, and the revolt in Ghent was quickly spreading across western Flanders. What's more, the Valois kings had always prioritized the north of the kingdom and so an attack there would be especially damaging to the French crown. On the downside, the French had a larger military presence in the north and would likely be expecting an attack via Calais or Cherbourg.

The second camp supported a southern strategy. The lord lieutenant had reported that the southwest was almost defenseless and the rebellions in Brittany and Flanders would surely continue to pull French attention away from Aquitaine. Gascony also neighbored Navarre, which desperately needed English support in its coming war against Castile. Of course, the distance was much greater and English shipping was limited.

On 10 October, the always meticulous Thomas Beauchamp, 12th earl of Warwick, brought together a group of London shipmasters to advise the Lords on the feasibility of the southern strategy. Warwick had been one of two admirals overseeing the 1378 campaign and had managed the logistics of moving thousands of men to Brest, Bordeaux, and eventually Saint-Malo. Warwick had but a few months to plan and execute his operation, though, and he suspected that a far larger effort could be managed with the greater lead time available to them now.

After three days of discussion, the shipmasters optimistically estimated that 1,500 men and horses could be transported to Bordeaux in the spring or twice that number of men without horses. This was an unexpected boon to the southern strategy. Neville had reported that the region was practically defenseless, and so the lords surmised that horses could be taken from the French in raids, which would allow the larger number of men to be sent. An army that size, when supplemented by local forces from the Anglo-Gascon lords and the routier companies, would represent the largest English force in Gascony since at least 1355. It had the potential to transform the situation in southern France and rescue Navarre.

On 17 October, as the Lords coalesced around the southern strategy, Edmund Mortimer, 3rd earl of March, rose to question its objectives. Gaunt, the chief advocate for a southern campaign, had significant personal interests in the area as the pretender king of Castile. March called out these interests now and asked whether English resources were meant to be used to advance Gaunt's cause.

March's objection was at least partly personal. He and Gaunt had been feuding since the Bad Parliament, when Gaunt supported the Black Prince's removal of March from the office of earl marshal. Gaunt had since declined to appoint March to any major position in the regency government. March also had serious financial interests to consider. The earl had been among the most generous supporters of Jean IV during the duke's exile in England. March took on significant debt in preparation for a 1375 campaign to Brittany, which was ultimately aborted. The southern strategy would handicap England's ability to support Jean if peace talks with the French fell through, and any setback for Jean in Brittany would also be a setback for March to recover debts he was owed by the duke.

Gaunt was furious, but he had no good answer for March's questions. He was not proposing that this army fight for him in Castile, but he did see a campaign in Castile as the only path to victory over France in the long run. He could not say it publicly, but he had come to believe that England could not defeat France so long as France was allied with Castile. He also believed the Franco-Castilian alliance would only be broken with an attack on Castile itself. This went hand-in-hand with his pretensions to the Castilian throne, but he had to be careful not to be seen as using his position as lord regent to advance his own claims abroad.

Two days later, William Ufford, 2nd earl of Suffolk, proposed a compromise plan. Instead of launching a major invasion of either the north or south in the hope of delivering a single knockout blow, Suffolk proposed smaller campaigns in both areas. He argued for reducing plans for the northern campaign from 5,000 men to 3,500 and the southern campaign from 3,000 to 1,500 so as to divide and overwhelm the French, who had to juggle crises in Brittany, Flanders and Languedoc. Warwick and Hugh Stafford, 2nd earl of Stafford, supported Suffolk's plan for a two-prong attack. Gaunt eventually agreed.

On 25 October, having finally settled on a plan of attack, Gaunt announced that March would be made lord lieutenant of Ireland. It was a subtle act of revenge. Sir William de Windsor, who served as lieutenant from 1369 to 1376, had run the lordship into the ground. Procuring five grants of taxation in just three years, he turned a large majority of the Anglo-Irish people against their own government. That few of the taxes he levied made their way into government coffers demonstrated the corruption and incompetence of his rule. Gaelic lordships rapidly expanded as Anglo-Irishmen deserted their positions for non-payment of wages. Despite the catastrophe, Windsor secured a second term in office thanks to the influence of his wife, Alice Perrers, who was Edward III's mistress. Windsor was removed from his position only after the Black Prince took control of his father's government in 1376. Windsor's successor, James Butler, 2nd earl of Ormond, had not been able to right the ship of state.

March knew the position was a poisoned chalice, but he could not refuse it. By law, his wife was the greatest landholder on the island, but her lands had been overrun by the Gaelic Irish. Taking the position was thus a matter of honor. What's more, he badly needed the position's salary to service his debts.

Henry Percy, 4th baron Percy, was similarly punished by Gaunt. Percy was a longtime ally of Gaunt's who had slowly drifted out of the duke's orbit. By 1379, Percy was more closely associated with March than any other member of the peerage. Told that he was needed in the north, Percy was made to resign the office of earl marshal so as to accept an appointment as warden of the western march. He was replaced as earl marshal by John Fitzalan, 1st baron Arundel, who was the younger brother of the earl of Arundel.

Tax commission

On 30 September, the Commons met in the Chapter House. They elected Sir John Gildesburgh as their speaker. Gildesburgh's origins are obscure. He may have been the son of a wealthy London fishmonger of the same name. He was definitely the nephew of Peter de Gildesburgh, a canon in Abbeville. Peter worked as a clerk in the exchequer in the 1330s before serving the Black Prince as a clerk for the duchy of Cornwall. In the latter position, Peter had his nephew John brought on as a squire for Sir Bartholomew Burghersh, son and heir of the baron Burghersh, who managed the Black Prince's household. Gildesburgh fought at Crécy and Poitiers as part of Burghersh's retinue and was knighted for his service. Burghersh's death in 1369 threatened to impoverish Gildesburgh, but he soon wed Margery Garnet, a minor Essex heiress. This brought him to the attention of Humphrey de Bohun, 7th earl of Hereford, who was the largest landholder in the area. Gildesburgh served Bohun until the earl's untimely death in 1373, at which time Gildesburgh joined the service of Bohun's son-in-law and heir jure uxoris, the earl of Buckingham.

The Commons was extremely hostile to the government's call for heavy taxation. The knightly class did not waver in its support for the war, but its members could not accept financial reality. In the 1350s, a boom in the wool trade had allowed the government to prosecute the war without raising taxes, but exports had declined from more than 32,000 woolsacks per year in the late 50s to barely 20,000 in the late 70s. Government revenue from the wool staple had thus declined by more than a third. Simply put, crown revenue alone could not support the war effort and tax revenue was needed. The Commons, however, suspected that fraud was the true reason for the government's shortfall. This was not a totally unreasonable assumption, given that the final years of King Edward III's reign had been plagued by fraud and abuse.

On 8 October, Gildesburgh delivered a request from the Commons for a more thorough account of the government's finances so as to "identify and remedy" the faults of the king's regency government. It was a scene uncomfortably reminiscent of the rise of the Commons during the Bad Parliament. Gaunt allowed the Commons to make a closer accounting of funds, but reminded Gildesburgh that the nobility was responsible for the defense of the realm. This was a subtle, ominous reminder that the Black Prince had imprisoned the speaker of the Commons in 1376 on the grounds that refusing to grant taxation in wartime exposed the realm to invasion and ruin, and was thus treasonous.

Thomas de Brantingham, bishop of Exeter and lord treasurer, provided a detailed summary of government income and expenditure. Brantingham was a highly competent official and was known on a personal level for his honesty and impartiality. His reputation and work ethic were such that the Commons could not question the veracity of his report. The suspicion of fraud was laid to rest, but Brantingham's report had given the Commons a new line of attack. Stunned by the maintenance costs of Brest, Calais, Cherbourg, and Saint-Malo, the Commons declared that tax revenues were meant exclusively for offensive operations and not for overhead costs such as these. When the Commons was asked to clarify whether it was advising the king to sell these positions back to the French, the response was a firm no. The Commons expected the crown to hold these fortresses, but for the crown to pay them itself, even after accepting Brantingham's report, which demonstrated this was not possible.

The position that the Commons had taken was ridiculous, but government officials made the mistake of calling it so. Chronicler Thomas Walsingham wrote that Gaunt privately mocked the intelligence of those serving in the Commons. Wykeham, who had vocally supported the reformers of the Bad Parliament, now attacked the Commons as uncooperative, unrealistic, and unsupportive of the war effort. The king, on Gaunt's advice, would not hear petitions from the Commons until a grant of taxation was approved. Unfortunately, this public browbeating only stiffened the resolve of the more radical members of the Commons.

As the crown and Commons hurtled toward another constitutional crisis, Gildesburgh stepped in to take control of the situation. His connections and military service made him uniquely qualified for diffusing the situation. Gildesburgh proposed creating and empowering a committee of 12—its members consisting of four barons, four bishops, and four knights—to settle the issue of taxation. Instead of making this proposal directly himself, he worked through his lord, Buckingham, to convince Gaunt that he (Gildesburgh) was not part of the more radical element of the Commons and was acting in good faith. Gaunt took his brother's recommendation and agreed to establish such a committee.

On 23 October, the bicameral committee of 12 met in the Star Chamber. Its lordly members included several longtime supporters of King Edward IV, though Gaunt ensured that his own interests were also represented with the inclusion of his northern retainer Guy de Bryan, 1st baron Bryan, and Ralph Ergham, bishop of Salisbury, who owed his advancement in the church to his relationship with Gaunt. William Courtenay, bishop of London, who was his own force in English politics, and Thomas Appleby, bishop of Carlisle, an accomplished diplomat and mediator of Anglo-Scottish disputes, were also included. Gildesburgh ensured that the more radical anti-tax element of the Commons was represented, appointing Sir John Annesley and Sir James Pickering, but also included the more pliable Sir Gerald Braybrooke as well as Sir Thomas Hungerford, a Lancastrian retainer sure to do as Gaunt instructed.

Annesley and Pickering were badly outnumbered and could not defend their position for very long. They had to recognize that the previous grant had led to successful campaigns in 1378 and 1379 and that the treasurer's report dispelled any notion of fraud. Their opposition to funding forward bases like Calais and Cherbourg was thus untenable. They conceded to the government's request for taxation, with caveats, after just two days of talks.

The first concession that Annesley and Pickering won appeared minor. They wanted fighting men to have a greater presence in government during a time of war. This was a thinly-veiled attack on Bishop Wykeham for his calling the Commons unsupportive of the war effort. Wykeham would be forced to resign the chancellorship and be replaced by a lay lord before the dissolution of parliament.

Annesley and Pickering's second demand was more substantive. The lords were made to acknowledge that the current level of taxation was unsustainable and that a double grant of taxation represented two years of revenue. In this, the Lords effectively agreed that no other taxes would be levied before fall 1381.

Gildesburgh immediately endorsed the committee's deal and worked tirelessly to sell it to his colleagues. He succeeded. The Commons approved a grant of two tenths and fifteenths, a two-year extension of the wool staple, and even a modest increase in the rate of the wool staple. The convocations of Canterbury and York approved a tax of two tenths on the church soon thereafter.

Treaty of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port

On 26 October, after the issue of taxes had been settled, Sir John Kentwood introduced a petition that called for a commission to resolve the issue of the king's mariage. Kentwood likely hoped that a bride would bring a sizable dowry and reduce the need for future taxation, but his petition soon became a diplomatic issue.

England and Navarre had signed the Treaty of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in August 1378, forming an alliance against France and Castile. The treaty detailed the two kingdoms' military commitments and was meant to be sealed with a marriage between Edward and one of the daughters of King Charles II of Navarre, with negotiations for the bride's financial settlement and delivery to follow. In October 1378, though, Charles's daughters were captured by the French at Breteuil and the treaty's marriage provisions had been an open question ever since.

The dowager Queen Joan beseeched Gaunt to reopen the search for a bride, worried that her son would become trapped in a martial limbo if he waited for a Navarrese princess to be released. Gaunt relented and, in March 1379, dispatched a small embassy to follow up on an offer from Bernabò Visconti, lord of Milan. This drew the attention of Pope Urban VI, who strongly discouraged the match, and the talks became ensnared in the poisonous politics of northern Italy.

Navarrese ambassadors had kept a constant presence at court over the past year. Gaunt had repeatedly offered assurances of English support as Navarre faced invasion from Castile, but the long history between the two kingdoms made the Navarrese skeptical of these promises. Navarre had betrayed the English in 1354 and 1359 and the English had reneged on deals with Navarre in 1370 and 1373.

The most recent delegation had been led by Prince Charles of Navarre, heir to the kingdom. His presence underscored the seriousness with which the king of Navarre was treating negotiations with the English. Still, the 18-year-old prince was only a figurehead. The real diplomatic work was handled by two of the king's closest officials, Jacques de Rue and Pierre du Tertre.

Rue and Tertre followed parliament's proceedings with growing dismay. Suffolk's plan to send the bulk of English forces to northern France and Kentwood's petition to settle the issue of the king's marriage had convinced the Navarrese that they were going to be betrayed again. They made a series of increasingly desperate offers to Gaunt as they tried to reaffirm the Anglo-Navarrese alliance. They proposed wedding one of the princesses to Gaunt's son and heir, Henry, so as to give Gaunt a personal interest in Navarre's defense, but Gaunt did not want to wait for the girl's ransom to settle his son's marriage. Rue and Tertre offered King Charles's bastard daughter to either Edward or Henry as a means of sealing a marriage between the two kingdoms immediately, but this was flatly rejected.

In late November, as the Navarrese delegation began planning their long journey home before winter, Rue and Tertre made a wild proposal to wed one of Gaunt's daughters and Prince Charles. This caught Gaunt off guard. King Charles had arranged for Prince Charles to wed one of the daughters of Enrique II in 1373, after the English broke an alliance with Navarre. The girl, Leonor de Trastámara, was only 13 at the time and the marriage was not celebrated for another two years. Though she was now 19, Rue and Tertre reported that the marriage was still unconsummated. Leonor reportedly hated Navarre, fought constantly with her husband, and had repeatedly sought to return to Castile.

Prince Charles was entirely ignorant of Rue and Tertre's proposal, even as they divulged the secret of his marital discord. Gaunt was intrigued by the offer, but leery of committing one of his daughters to a potentially bigamous marriage in the event that the Navarrese were mistaken about the nonconsummation. He agreed only on the condition that one of his Castilian supporters, Juan Gutiérrez, former dean of Segovia, return with them to Pamplona and be allowed to investigate the claim himself.

Woodstock-Brembre affair

On 28 October, as parliament neared the end of its business, Buckingham accused a gang associated with London Mayor Nicholas Brembre of attacking several men in the earl's employ. Buckingham charged that his men were beaten and wounded, then chased by Brembre's men. Buckingham's men sought refuge in Buckingham's London townhouse and Brembre's men had inflicted a great deal of damage on the house trying to get in.

The charges were explosive. London was the third rail of medieval English politics. Gaunt's reputation had suffered badly for his support of John Northampton, a draper whose attacks on London's merchant oligarchs had drawn many of the city's craftsmen and smaller merchants to him, forming the base of a reformist party. Gaunt had no real interest in Northampton's broader agenda, but was strongly attracted to Northampton's plan to bring down the oligarchy, which Gaunt thought had grown too powerful and become a threat to the crown.

Brembre was a tool of the Fishmongers Guild, the most powerful company in the oligarch party. The leader of the Fishmongers, William Walworth, feared that Buckingham's charges would lead parliament to impose new statutes on the city. Walworth forced Brembre to arrest the perpetrators and then present himself to parliament and make peace with Buckingham.

The mayor spoke powerfully in his own defense. He reported that the hooligans had been arrested and he offered £100 to cover the damages to Buckingham's townhouse. This satisfied parliament, but Buckingham continued to fume privately. Walworth, not wanting to start a feud with the young earl, wrote off 1,000 marks in loans to the crown to buy a royal pardon for Brembe so as to ensure that neither Buckingham nor Gaunt could pursue the issue further.

Aftermath

The parliament of 1379 reshaped English politics in ways that few could have foreseen. Firstly, it established the young earl of Buckingham as a newfound political powerhouse. His campaign in Brittany had brought him glory like few others of his generation had experienced, he spoke powerfully in the Lords, and his connection to the speaker was instrumental to settling the tax standoff with the Commons. The short-lived Brembre affair proved that he was one of the few figures who could threaten the oligarchs, kicking off a new era of royal interest in London politics.

Secondly, Wykeham's forced resignation from the chancellorship cleared the way for Gaunt to remake the regency government in his image. Gaunt and Wykeham had been at odds since 1371 and Wykeham had been made chancellor in 1376 by the Black Prince. Wykeham was kept in the position only to provide continuity with the short-lived government of Edward IV, but he had been a useful check on Gaunt's worst tendencies for favoritism and revenge. These were already on display within days of Wykeham's resignation, as March and Percy were effectively exiled to their new positions far from court. As Gaunt tightened his grip on government, English foreign policy began to intertwine with Gaunt's own ambitions in Castile.

On 6 December, Gaunt sealed two sets of letters with regard to Navarre. The first he sealed as lord regent of England, reconfirming the military commitments of the Treaty of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. He ordered the lord lieutenant of Aquitaine to make 1,500 men available for the defense of Navarre in the spring and a loan of £4,000 was extended to Navarre. Gaunt sealed the second set of letters as king of Castile, committing himself to an alliance with Navarre and betrothing his daughter Elizabeth to Prince Charles, pending an investigation by Gutiérrez.

Then, on 10 December, Gaunt secretly dispatched Juan Fernández de Andeiro to Portugal. Andeiro was a Galician nobleman who'd facilitated negotiations between England and Portugal in the early 1370s and had become a member of Gaunt's Castilian court in exile. Andeiro had quietly received a message in the fall that King Fernando of Portugal was open to the possibility of a marriage alliance with England. Gaunt had spent weeks consulting with Andeiro and trading messages with the dowager queen. Now, Andeiro was to put forward Richard of Bordeaux for the hand of Beatriz de Portugal, Fernando's only child and heiress.

Just four days after Andeiro departed for Lisbon, the veteran Gascon diplomat Geraud de Menta was sent off to Barcelona to bring King Pere IV of Aragon into the emerging pan-Iberian alliance against Trastámaran Castile. Gaunt gave de Menta broad discretion to deal with the Aragonese, even to extend Philippa of Lancaster's hand in marriage if needed.

Gaunt left his grand Savoy Palace soon after launching the mission to Barcelona. Lancastrian account books show that he hosted Edward, Joan and Richard at Kenilworth Castle for Christmas. It is likely here that Gaunt, feeling more secure in his position as regent than he ever had before, agreed to Joan's request that he reconsider an imperial match for the young king.

The Parliament of 1379, sometimes known as Buckingham's parliament, was a session of the English parliament held at Westminster Palace from 29 September to 1 November 1379. It was the fourth assembly of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal and the second full parliament of the reign of King Edward V of England.

Background

Edward V succeeded to the throne upon the death of his father, King Edward IV, in 1377. John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, was made lord regent for the new king, who was just 12.

Gaunt was arguably the only figure with the stature to lead a regency government. He was Edward IV's eldest surviving brother and, as duke of Lancaster, he held the greatest landed estate in England besides the crown itself. He was, however, arrogant, domineering, and highly sensitive to encroachments upon his or the crown's authority, and he had made many powerful enemies as a result. He initially refused the regency, believing that he would not be given credit for its successes and would be blamed for its failures. He hoped instead to pursue his own ambitions in Castile, but Queen Joan, with whom he had a strong friendship, ultimately persuaded him to accept Edward IV's settlement of the regency.

Gaunt was forced to make a series of concessions and public apologies to his various enemies in order to secure the regency and stabilize his young nephew's government, but either he harbored no resentment for the political penance he was made to perform or he hid it uncharacteristically well. Gaunt ultimately took control of the government with little controversy and governed with the support of the upper nobility.

The first parliament of the new reign met in early 1378. The brief reign of Edward IV in summer 1377 had seen the renewal of hostilities with France, which included assaults on all English positions on the continent and the first major attack on the English mainland since the 1330s. Shocked by these attacks, the Commons approved a double grant of taxation to finance plans for a major continental offensive. Chroniclers heralded this as an extraordinary demonstration of support for the new boy king, but in reality such heavy taxation was needed to move the war back onto French territory.

The 1378 grant brought royal revenue to a height not seen since the early 1360s. The English thus had a brief window of time in which they could compete with French military spending nearly pound for pound as they sought to launch a major offensive in Brittany, bolster local action in Gascony, and rebuild their defenses along the southern English coast.

War in France

Brittany became the target of English ambition as they planned to retake the initiative in 1378. A major force was to land at Brest and move north to capture a string of ports along the Breton coast, but a poorly-planned attack on Normandy left too few ships to transport the army to Brest and the expedition never materialized. Only a fraction of the army made its way to Brest while the rest was redirected east to attack Saint-Malo.

The English captured Saint-Malo, one of the greatest and most heavily fortified ports in Brittany, after a short, but fierce siege. They soon gained another great fortress-port, as a newly-negotiated alliance with Navarre brought Cherbourg under English control. The Anglo-Navarrese suffered a major setback, though, when Navarre's other Norman possessions quickly fell to the French. England and France ended 1378 in something of a draw, much as they had the previous year.

In spring 1379, the Breton nobility banded together in opposition to the French crown's attempt to annex the duchy and soon rebelled. Their early efforts were focused in the east, where the duchy's principal cities lay and which was most exposed to French attack. In the west, the English maintained a small army at Brest under the command of Thomas of Woodstock, 1st earl of Buckingham.

Buckingham led an expeditionary force to Morlaix and discovered towns and villages open to him along the way. The local population mistakenly believed the English were allies of the Breton nobility and welcomed Buckingham's men as liberators. Buckingham quickly exploited the situation and rolled over western Brittany. By mid summer, the ports of Morlaix and Saint-Pol-de-Léon were garrisoned by Buckingham's men, effectively bringing all of Léon under English control.

The French response to the Breton rebellion was chaotic. The crown was at first belligerent and raised a small army with the intent to invade, but then abruptly called off the attack and attempted to find a diplomatic solution.

In Normandy, Bertrand du Guesclin, constable of France, avoided the rebellion in his native Brittany by volunteering to lead an assault on Cherbourg. Many at the time considered the fortress to be impregnable and Guesclin soon came to the same conclusion. He arrived in the spring with an army of about 1,200, but was slowly bled of men and supplies. Scouting parties were routinely ambushed, leading to the capture of several hostages, including Guesclin's brother and cousin, and the French war camp suffered repeated attacks from English sorties. Gueclin abandoned the effort and returned to Paris in August.

As the French crown was preoccupied with events in northern France, it lost control of the south. Tax riots broke out across Languedoc in the spring. The region had been forced to bear disproportionately high taxes through the 1370s and the latest grant came despite there being no major action against the English in the region. The tax was never collected, though it was not officially canceled, as local administrators simply refused to act for fear of being lynched. The seneschals of the region begged Paris for advice on how to proceed.

The two great lords of the south, the count of Armagnac and the count of Foix, could not fill the leadership vacuum left by the French crown because they were at war with one another. The count of Comminges had died in 1376, leaving his young daughter as his only heiress. Armagnac and Foix had been fighting for control of the girl and her lands ever since.

The English exploited the chaos in southern France just as efficiently as they had the chaos in Britany. The lord lieutenant of Aquitaine brought the local Anglo-Gascon nobility into his administration, secured the approach to Bordeaux, and swept French garrisons out of the Gascon marches. He encountered no practical resistance, exposing the profound weakness of the French crown south of the Loire.

The English in France, 1379

Red: Territories of King Edward V of England

Light red: Gascon marches, controlled by local lords

Very light red: Range of routier company raiding parties

Dark/mustard yellow: Major castles controlled by the routiers

Orange: Norman estates of King Charles II of Navarre, lost 1378

Light green: Territories of Jean II, count of Armagnac

Lavender: Territories of Gaston III, count of Foix

Finances

In early 1378, the government estimated that it needed £200,000 to cover the cost of the planned war effort, but only about £45,000 was expected from ordinary revenue over the course of that year. Even with the double grant of taxation provided by parliament, there was a projected deficit of about £50,000. The Commons believed that better administration of the royal demesne could make up the difference, but this was fanciful. Administrative changes alone could not realistically be expected to more than double ordinary revenue.

Operations in the north of France ran wildly over budget. The cost to supply Brest and pay the wages of its garrison had been estimated at £5,000, but the true cost was closer to £12,000 in 1378 and £10,000 more was needed to resupply the town and finance the earl of Buckingham's campaign in 1379. A new alliance with Navarre brought Cherbourg under English control, an unplanned budget item that cost £10,000 in its first year and another £8,000 in its second. The newly-captured fortress port at Saint-Malo needed not just supplies and wages, but its walls rebuilt following its conquest, bringing costs to more than £20,000 over the course of 1378 and 1379.

The government kept pace with the soaring cost of the war for a time, finding ways to cut spending and raise new revenue. It began by partially offloading defense spending. The country's decentralized coast guard system had worked fairly well at turning back the French attacks on southern England in summer 1377. Now, that system was to be decentralized further. The government leaned on knightly families that had grown rich off the capture and ransom of French prisoners over the course of the war to fortify their lands along the coast. The effort was hugely successful and more licenses to crenellate were issued in 1378 and 1379 than any other two-year period on record.

Defense spending could not be entirely outsourced to the lower nobility, though. In particular, long-neglected fortresses on the Channel Islands required immediate attention. Thousands of pounds were poured into Castle Cornet on Guernsey and Castle Goring on Jersey to build new circuits of walls and fully garrison them for the first time since the early 70s.

As the crown looked to find new sources of revenue, Gaunt stepped in to revive the stalled negotiations for the ransom of Waleran III, count of Saint-Pol. The count had been captured in a skirmish outside Calais in 1374 and the English crown had acquired custody of him soon thereafter. Saint-Pol was one of the great magnates of northern France and so the English expected an enormous sum for his release. Negotiations were complicated, though, by the English insistence that several prisoners of the French crown be released as partial payment toward Saint-Pol's ransom. Saint-Pol had few friends at the French court and the English demands were rejected out of hand. As neither side was prepared to budge, Saint-Pol became stuck. Gaunt, however, dropped demands for a prisoner exchange, cutting the French crown out of the process. Talks for a more straightforward financial transaction soon began and Saint-Pol agreed to a ransom of 150,000 francs (£25,000).

In October 1378, news reached England that the college of cardinals, which was dominated by the French, had declared the election of Pope Urban VI invalid and had instead elected Cardinal Robert de Genève, who took the name Clement VII. The schism in the church was a boon for the English treasury.

Gaunt immediately saw the opportunity the election of a French antipope presented. He had been made to end his public support of religious reformer John Wycliffe in 1377, but he had lost none of his interest in disendowing the church, as Wycliffe preached. As English bishops declared for Urban, Gaunt issued a decree that all the cardinals obedient to Clement were to be deprived of their offices and benefices in England and Aquitaine. He followed it soon after with another decree disendowing all foreign monastic houses, which had been suspected of French collaboration for many decades. The two orders brought thousands of pounds into the treasury and lands worth upwards of £8,000 per annum were added to the royal demesne.

Despite these efforts, the government eventually exhausted its funds, but it found ready creditors among the mercantile classes. Castile had wreaked havoc on English trade and the growth of French naval power posed an even greater threat to trade in the future. English merchants thus took a great interest in the string of royal fortresses that had begun to emerge along the Channel, stretching from Brest to Saint-Malo, the Channel Islands and Cherbourg and then on to Calais. This defensive line promised to protect English shipping and, with it, the wealth of the merchant oligarchy. Tens of thousands of pounds were loaned at low or even no interest to encourage the buildup of these areas.

The government's most generous lenders came from the grocers company and the fishmongers guild, where just four men would loan £10,000 between them, but the merchant class was not alone in lending funds. Thousands of pounds in new loans were negotiated with members of the upper nobility in January 1379 and a £5,000 loan was forced upon the city of London in February.

The government's new forward defensive strategy did coincide with a decline in attacks on shipping in the English Channel and southern coastal towns in 1378 and 1379, but there was a marked increase in attacks on shipping in St. George's Channel and coastal towns in Cornwall, Ireland and Wales. In short, this strategy did not so much end the Castilian and French naval threat as it did shift their targets to less fortified positions in the west. As attacks increased, requests for funds flooded in from Caernarfon, Dublin, and Plymouth. It was clear that the government required new taxation and summons for parliament were issued on 4 July.

Great council

The Lords Spiritual and Temporal gathered at Westminster Palace in early September. The upper nobility had been instrumental to the early success of Gaunt's government. The assembly of a great council in January 1378 had allowed the Lords to set the agenda for the parliament that followed and subsequent great councils had advised the government on the conduct of the war as events unfolded.

On 9 September, Edward V presided as the great council convened in the White Chamber. As had become the norm in the new reign, the young king largely kept his silence through the proceedings and referred all matters and questions to his avuncular regent and the ministers of his government. Edward paid close attention even to formalities, such as the opening prayer and the treasurer's report on finances, to which very few lords cared to listen, as no taxes could be levied in the absence of the Commons. The lords waited impatiently for a report on the situation in Brittany.

Jean IV, duke of Brittany, had sat as earl of Richmond in the three prior great councils of Edward V's reign. The English had supported Jean's claim to Brittany for decades, fighting for his cause in the 1350s and 60s and giving him financial support during his exile in the 70s. The Breton nobility had invited Jean to return to Brittany shortly after launching their rebellion in the spring, but Jean was initially skeptical of their intentions and delayed going until summer. Jean had been back on the continent for more than a month by the time the Lords met. They cheered word of his safe arrival, but there was little other news from the duke.

Buckingham, just 22 years old, then rose to speak of his own time in Brittany. His report made a major impression on the lords. The capture of Morlaix and Saint-Pol-de-Léon, in addition to existing control of Brest and Saint-Malo, gave the English four major ports by which they could enter Brittany. Buckingham drank in the glory, as not even the famed William de Bohun, 1st earl of Northampton, had been able to capture Morlaix during his campaigns in the 1340s.

The success of his first command convinced Buckingham of the superiority of English arms and of his own skill as a commander. He appeared to have little appreciation for the unique circumstances that had allowed him to so rapidly expand the area of English control. He boldly declared that the French were on the back foot and that, with Jean restored to the ducal throne, an English expedition in 1380 could join forces with Brittany and win the war once and for all.

Gaunt brought the Lords back to reality with news from Pamplona. The death of King Enrique II of Castile had saved the kingdom of Navarre from Castilian invasion in 1379, but the new King Juan was determined to pick up where his father had left off. A spring invasion was certain and Navarre had no chance of survival without English support. Buckingham's call for a new expedition to Brittany was overtaken by the situation in Navarre, much to the young earl's frustration. Over the next several days, though, a rush of news from the continent would overwhelm talk of action in either Brittany or Navarre.

First, a flurry of confusing reports poured in from Flanders. The great town of Ghent, which had been simmering with grievances and resentments all through the summer, had finally boiled over into revolt. A local militia known as the White Hoods had lynched the town's bailiff and sacked the residence of Louis II, count of Flanders. The town's council had been removed and replaced with the militia's leaders. The nearby town of Courtrai had already declared its support for the White Hoods and joined Ghent's rebellion against the count.

Then, a squire from Bordeaux arrived with news of the campaign in the Gascon marches. Dozens of enemy positions and great stores of food and supplies had been captured. The Anglo-Gascons had encountered no resistance and earned a small fortune from plunder and patis. The lord lieutenant needed reinforcements to push further into French territory in 1380.

Finally, word came from Brittany. Jean had agreed to a six-month truce with the French and peace talks were set to follow. Anger and confusion followed this last report. The lords had expected Jean to return their decades of support with an alliance against the French.

The lords were overwhelmed by the events in France. Debate as to how they should proceed went in circles, leading to arguments and acrimony. Days ticked by, but there was no consensus to be found as the Commons gathered at Westminster.

In session

The Commons assembled at Westminster Palace in late September. The lower nobility and townsmen had challenged royal government on several occasions in the 1370s, culminating in a dramatic showdown with the Black Prince in the Bad Parliament. The prince's arrest of the speaker of the Commons was a scandal, but the Black Prince was an enormously popular figure, well known for his charm, courtesy, and incredible feats of arms. Gaunt, however, was known for none of these things. He had carefully managed his dealings with the Commons in 1378 to avoid another major showdown, but disagreement in the Lords as to the best path forward had left parliament's agenda wide open in 1379.

On 29 September, Edward V presided as the two houses of parliament met in the Painted Chamber. Simon Sudbury, archbishop of Canterbury, gave a long sermon imploring all those in attendance to work together for the betterment of the realm and the mending of Christendom in a time of schism. William of Wykeham, bishop of Winchester and lord chancellor, then rose to address the parliament as to the reason for their assembly. He recounted the great support that had been shown in the last parliament and detailed the actions that had been taken in the various theaters of war. Then, shocking and horrifying the Commons, Wykeham reported the government's financial position as a result of these actions and called for a second double grant of taxation. Finally, the young king rose to give a short speech in which he formally asked those assembled to offer him their counsel on these matters. The business of the day ended there and a feast was held to celebrate Michaelmas, which was organized at the suggestion of the king.

Plan of attack

On 30 September, the Lords returned to the White Chamber to devise a plan of attack. It appeared France was on the precipice—Brittany had rebelled and almost completely evicted the French, Neville had found no resistance in the Gascon marches, and now Ghent was in revolt. The lords began to share Buckingham's belief that they could bring the war to a close with another major offensive.

Two camps emerged. The first supported a northern strategy. England now held several positions along the northern coast of France from which they could launch an attack, Jean IV remained a possible ally if his negotiations with the French fell through, and the revolt in Ghent was quickly spreading across western Flanders. What's more, the Valois kings had always prioritized the north of the kingdom and so an attack there would be especially damaging to the French crown. On the downside, the French had a larger military presence in the north and would likely be expecting an attack via Calais or Cherbourg.

The second camp supported a southern strategy. The lord lieutenant had reported that the southwest was almost defenseless and the rebellions in Brittany and Flanders would surely continue to pull French attention away from Aquitaine. Gascony also neighbored Navarre, which desperately needed English support in its coming war against Castile. Of course, the distance was much greater and English shipping was limited.

On 10 October, the always meticulous Thomas Beauchamp, 12th earl of Warwick, brought together a group of London shipmasters to advise the Lords on the feasibility of the southern strategy. Warwick had been one of two admirals overseeing the 1378 campaign and had managed the logistics of moving thousands of men to Brest, Bordeaux, and eventually Saint-Malo. Warwick had but a few months to plan and execute his operation, though, and he suspected that a far larger effort could be managed with the greater lead time available to them now.

After three days of discussion, the shipmasters optimistically estimated that 1,500 men and horses could be transported to Bordeaux in the spring or twice that number of men without horses. This was an unexpected boon to the southern strategy. Neville had reported that the region was practically defenseless, and so the lords surmised that horses could be taken from the French in raids, which would allow the larger number of men to be sent. An army that size, when supplemented by local forces from the Anglo-Gascon lords and the routier companies, would represent the largest English force in Gascony since at least 1355. It had the potential to transform the situation in southern France and rescue Navarre.

On 17 October, as the Lords coalesced around the southern strategy, Edmund Mortimer, 3rd earl of March, rose to question its objectives. Gaunt, the chief advocate for a southern campaign, had significant personal interests in the area as the pretender king of Castile. March called out these interests now and asked whether English resources were meant to be used to advance Gaunt's cause.

March's objection was at least partly personal. He and Gaunt had been feuding since the Bad Parliament, when Gaunt supported the Black Prince's removal of March from the office of earl marshal. Gaunt had since declined to appoint March to any major position in the regency government. March also had serious financial interests to consider. The earl had been among the most generous supporters of Jean IV during the duke's exile in England. March took on significant debt in preparation for a 1375 campaign to Brittany, which was ultimately aborted. The southern strategy would handicap England's ability to support Jean if peace talks with the French fell through, and any setback for Jean in Brittany would also be a setback for March to recover debts he was owed by the duke.

Gaunt was furious, but he had no good answer for March's questions. He was not proposing that this army fight for him in Castile, but he did see a campaign in Castile as the only path to victory over France in the long run. He could not say it publicly, but he had come to believe that England could not defeat France so long as France was allied with Castile. He also believed the Franco-Castilian alliance would only be broken with an attack on Castile itself. This went hand-in-hand with his pretensions to the Castilian throne, but he had to be careful not to be seen as using his position as lord regent to advance his own claims abroad.

Two days later, William Ufford, 2nd earl of Suffolk, proposed a compromise plan. Instead of launching a major invasion of either the north or south in the hope of delivering a single knockout blow, Suffolk proposed smaller campaigns in both areas. He argued for reducing plans for the northern campaign from 5,000 men to 3,500 and the southern campaign from 3,000 to 1,500 so as to divide and overwhelm the French, who had to juggle crises in Brittany, Flanders and Languedoc. Warwick and Hugh Stafford, 2nd earl of Stafford, supported Suffolk's plan for a two-prong attack. Gaunt eventually agreed.

On 25 October, having finally settled on a plan of attack, Gaunt announced that March would be made lord lieutenant of Ireland. It was a subtle act of revenge. Sir William de Windsor, who served as lieutenant from 1369 to 1376, had run the lordship into the ground. Procuring five grants of taxation in just three years, he turned a large majority of the Anglo-Irish people against their own government. That few of the taxes he levied made their way into government coffers demonstrated the corruption and incompetence of his rule. Gaelic lordships rapidly expanded as Anglo-Irishmen deserted their positions for non-payment of wages. Despite the catastrophe, Windsor secured a second term in office thanks to the influence of his wife, Alice Perrers, who was Edward III's mistress. Windsor was removed from his position only after the Black Prince took control of his father's government in 1376. Windsor's successor, James Butler, 2nd earl of Ormond, had not been able to right the ship of state.

March knew the position was a poisoned chalice, but he could not refuse it. By law, his wife was the greatest landholder on the island, but her lands had been overrun by the Gaelic Irish. Taking the position was thus a matter of honor. What's more, he badly needed the position's salary to service his debts.

Henry Percy, 4th baron Percy, was similarly punished by Gaunt. Percy was a longtime ally of Gaunt's who had slowly drifted out of the duke's orbit. By 1379, Percy was more closely associated with March than any other member of the peerage. Told that he was needed in the north, Percy was made to resign the office of earl marshal so as to accept an appointment as warden of the western march. He was replaced as earl marshal by John Fitzalan, 1st baron Arundel, who was the younger brother of the earl of Arundel.

Tax commission

On 30 September, the Commons met in the Chapter House. They elected Sir John Gildesburgh as their speaker. Gildesburgh's origins are obscure. He may have been the son of a wealthy London fishmonger of the same name. He was definitely the nephew of Peter de Gildesburgh, a canon in Abbeville. Peter worked as a clerk in the exchequer in the 1330s before serving the Black Prince as a clerk for the duchy of Cornwall. In the latter position, Peter had his nephew John brought on as a squire for Sir Bartholomew Burghersh, son and heir of the baron Burghersh, who managed the Black Prince's household. Gildesburgh fought at Crécy and Poitiers as part of Burghersh's retinue and was knighted for his service. Burghersh's death in 1369 threatened to impoverish Gildesburgh, but he soon wed Margery Garnet, a minor Essex heiress. This brought him to the attention of Humphrey de Bohun, 7th earl of Hereford, who was the largest landholder in the area. Gildesburgh served Bohun until the earl's untimely death in 1373, at which time Gildesburgh joined the service of Bohun's son-in-law and heir jure uxoris, the earl of Buckingham.

The Commons was extremely hostile to the government's call for heavy taxation. The knightly class did not waver in its support for the war, but its members could not accept financial reality. In the 1350s, a boom in the wool trade had allowed the government to prosecute the war without raising taxes, but exports had declined from more than 32,000 woolsacks per year in the late 50s to barely 20,000 in the late 70s. Government revenue from the wool staple had thus declined by more than a third. Simply put, crown revenue alone could not support the war effort and tax revenue was needed. The Commons, however, suspected that fraud was the true reason for the government's shortfall. This was not a totally unreasonable assumption, given that the final years of King Edward III's reign had been plagued by fraud and abuse.

On 8 October, Gildesburgh delivered a request from the Commons for a more thorough account of the government's finances so as to "identify and remedy" the faults of the king's regency government. It was a scene uncomfortably reminiscent of the rise of the Commons during the Bad Parliament. Gaunt allowed the Commons to make a closer accounting of funds, but reminded Gildesburgh that the nobility was responsible for the defense of the realm. This was a subtle, ominous reminder that the Black Prince had imprisoned the speaker of the Commons in 1376 on the grounds that refusing to grant taxation in wartime exposed the realm to invasion and ruin, and was thus treasonous.

Thomas de Brantingham, bishop of Exeter and lord treasurer, provided a detailed summary of government income and expenditure. Brantingham was a highly competent official and was known on a personal level for his honesty and impartiality. His reputation and work ethic were such that the Commons could not question the veracity of his report. The suspicion of fraud was laid to rest, but Brantingham's report had given the Commons a new line of attack. Stunned by the maintenance costs of Brest, Calais, Cherbourg, and Saint-Malo, the Commons declared that tax revenues were meant exclusively for offensive operations and not for overhead costs such as these. When the Commons was asked to clarify whether it was advising the king to sell these positions back to the French, the response was a firm no. The Commons expected the crown to hold these fortresses, but for the crown to pay them itself, even after accepting Brantingham's report, which demonstrated this was not possible.

The position that the Commons had taken was ridiculous, but government officials made the mistake of calling it so. Chronicler Thomas Walsingham wrote that Gaunt privately mocked the intelligence of those serving in the Commons. Wykeham, who had vocally supported the reformers of the Bad Parliament, now attacked the Commons as uncooperative, unrealistic, and unsupportive of the war effort. The king, on Gaunt's advice, would not hear petitions from the Commons until a grant of taxation was approved. Unfortunately, this public browbeating only stiffened the resolve of the more radical members of the Commons.

As the crown and Commons hurtled toward another constitutional crisis, Gildesburgh stepped in to take control of the situation. His connections and military service made him uniquely qualified for diffusing the situation. Gildesburgh proposed creating and empowering a committee of 12—its members consisting of four barons, four bishops, and four knights—to settle the issue of taxation. Instead of making this proposal directly himself, he worked through his lord, Buckingham, to convince Gaunt that he (Gildesburgh) was not part of the more radical element of the Commons and was acting in good faith. Gaunt took his brother's recommendation and agreed to establish such a committee.

On 23 October, the bicameral committee of 12 met in the Star Chamber. Its lordly members included several longtime supporters of King Edward IV, though Gaunt ensured that his own interests were also represented with the inclusion of his northern retainer Guy de Bryan, 1st baron Bryan, and Ralph Ergham, bishop of Salisbury, who owed his advancement in the church to his relationship with Gaunt. William Courtenay, bishop of London, who was his own force in English politics, and Thomas Appleby, bishop of Carlisle, an accomplished diplomat and mediator of Anglo-Scottish disputes, were also included. Gildesburgh ensured that the more radical anti-tax element of the Commons was represented, appointing Sir John Annesley and Sir James Pickering, but also included the more pliable Sir Gerald Braybrooke as well as Sir Thomas Hungerford, a Lancastrian retainer sure to do as Gaunt instructed.

Annesley and Pickering were badly outnumbered and could not defend their position for very long. They had to recognize that the previous grant had led to successful campaigns in 1378 and 1379 and that the treasurer's report dispelled any notion of fraud. Their opposition to funding forward bases like Calais and Cherbourg was thus untenable. They conceded to the government's request for taxation, with caveats, after just two days of talks.

The first concession that Annesley and Pickering won appeared minor. They wanted fighting men to have a greater presence in government during a time of war. This was a thinly-veiled attack on Bishop Wykeham for his calling the Commons unsupportive of the war effort. Wykeham would be forced to resign the chancellorship and be replaced by a lay lord before the dissolution of parliament.

Annesley and Pickering's second demand was more substantive. The lords were made to acknowledge that the current level of taxation was unsustainable and that a double grant of taxation represented two years of revenue. In this, the Lords effectively agreed that no other taxes would be levied before fall 1381.

Gildesburgh immediately endorsed the committee's deal and worked tirelessly to sell it to his colleagues. He succeeded. The Commons approved a grant of two tenths and fifteenths, a two-year extension of the wool staple, and even a modest increase in the rate of the wool staple. The convocations of Canterbury and York approved a tax of two tenths on the church soon thereafter.

Treaty of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port

On 26 October, after the issue of taxes had been settled, Sir John Kentwood introduced a petition that called for a commission to resolve the issue of the king's mariage. Kentwood likely hoped that a bride would bring a sizable dowry and reduce the need for future taxation, but his petition soon became a diplomatic issue.

England and Navarre had signed the Treaty of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in August 1378, forming an alliance against France and Castile. The treaty detailed the two kingdoms' military commitments and was meant to be sealed with a marriage between Edward and one of the daughters of King Charles II of Navarre, with negotiations for the bride's financial settlement and delivery to follow. In October 1378, though, Charles's daughters were captured by the French at Breteuil and the treaty's marriage provisions had been an open question ever since.

The dowager Queen Joan beseeched Gaunt to reopen the search for a bride, worried that her son would become trapped in a martial limbo if he waited for a Navarrese princess to be released. Gaunt relented and, in March 1379, dispatched a small embassy to follow up on an offer from Bernabò Visconti, lord of Milan. This drew the attention of Pope Urban VI, who strongly discouraged the match, and the talks became ensnared in the poisonous politics of northern Italy.

Navarrese ambassadors had kept a constant presence at court over the past year. Gaunt had repeatedly offered assurances of English support as Navarre faced invasion from Castile, but the long history between the two kingdoms made the Navarrese skeptical of these promises. Navarre had betrayed the English in 1354 and 1359 and the English had reneged on deals with Navarre in 1370 and 1373.

The most recent delegation had been led by Prince Charles of Navarre, heir to the kingdom. His presence underscored the seriousness with which the king of Navarre was treating negotiations with the English. Still, the 18-year-old prince was only a figurehead. The real diplomatic work was handled by two of the king's closest officials, Jacques de Rue and Pierre du Tertre.