Thou Shalt Not Kill

Dr. Peter A. Pedersen

The Australian had a reputation as the most undisciplined soldier in the British Expeditionary Force. One hundred and twenty-one Australians were sentenced to death, the majority for desertion, during the war.

None were executed because Australian military law all but forbade capital punishment. Moreover, domestic antipathy to the death penalty in the AIF was etched in stone and governments attempting to introduce conscription could not afford to challenge it. Those attempts failed anyway. The Australian soldier remained a volunteer free from the threat of extreme sanction. His country would have it no other way.

When the Australian colonies federated on 1 January 1901, they ceded responsibility for defence to the new Commonwealth Government. In 1903, it brought the various colonial military forces under a single binding piece of legislation, the Australian Defence Act, which enshrined the principle of a defence force comprised of volunteers who could not be compelled to serve outside Australia or its territories. Section 98 of the Act governed the use of capital punishment. It relied heavily on the relevant provisions in the colonial defence legislation of New South Wales, Queensland and Tasmania, which reflected concerns that local forces should remain under local control.

The execution by British authorities of two Australian officers, Morant and Handcock, for the killing of Boer prisoners in South Africa was a lesser influence because the case aroused little public controversy in Australia at the time.

Under Section 98, only mutiny, desertion to the enemy and certain forms of treachery were punishable by death and the sentence had to be confirmed by the Australian Governor-General rather than a commander in the field. The small number of capital offences prescribed under Section 98 is striking compared to the range of offences punishable by death in the British Army.

And unlike the Canadian, South African and New Zealand governments, which agreed to their soldiers being tried and punished under the British Army Act, the Australian government insisted on the primacy of Section 98 when its troops served under British command.

Like voluntarism, a more lenient disciplinary code seemed appropriate for a culture considered, not without reason, as independent, resourceful and freer from class distinction than most. Its soldiers had never in their lives known any restraint that was not self-imposed. But even by this standard, discipline in the Australian Imperial Force had all but collapsed within a month of its arrival in Egypt in November 1914.

Under pressure from his British superiors, Maj-Gen. Bridges, the commander of the 1st Australian Division, ordered the return of 131 persistent offenders to Australia for discharge, together with 24 venereal cases. An official despatch explaining to the Australian public why the men were being sent home fulfilled the exemplary function of the punishment. In the absence of the death penalty, it remained the most dreaded instrument of discipline among Australian soldiers.

Unlike Egypt, Anzac was conducive to the maintenance of discipline. As the bridgehead was barely one mile square, it did not have a ‘rear’ where alcohol and women were available to tempt potential deserters.

Nevertheless, on 9 July an Australian court-martial sentenced a soldier to death for falling asleep on sentry to demonstrate the gravity of the offence and ensure a heavy prison sentence was awarded in lieu of a punishment that was bound to be commuted. Two more death sentences were passed on Australians at Gallipoli.

On the Western Front, the AIF lacked the independence granted by the isolation of its enclave at Anzac. It fought directly alongside British and other Dominion troops who were liable to the death penalty. The difficulty of having soldiers in the same army subject to different laws arose almost immediately after the AIF arrived in France in March 1916.

When an Australian soldier was sentenced to death in April and another in May, the commander of 1 ANZAC, Lt-Gen. Birdwood, recommended that the Australian Government should be asked to waive Section 98, thereby putting its troops on the same footing as the rest of the British Army. Haig forwarded the request to the War Office with his endorsement. On 9 July, London asked the Commonwealth to place Australian overseas troops under the British Army Act forthwith. As it was considering the introduction of conscription to remedy declining voluntary enlistment, the government delayed its answer.

Over the next two months the four Australian divisions in France suffered 28,000 casualties, precipitating the government’s decision on conscription. It called for a referendum at the end of October. Though the campaign split the nation, all Australians opposed the infliction of the death penalty on men who had volunteered to fight in a distant land in a cause not particularly their own. Even a hint that the revocation of Section 98 might be considered would have left conscription with no chance. Its defeat in the referendum all but precluded any measure that would discourage voluntary recruiting, making change even more remote.

The British request concerning Section 98 remained in abeyance.

But it would not go away. The effects of the 1916 battles went beyond the huge losses, which were eventually made good. They were forever seared in the minds of the survivors. For men whose nerve had gone, the concept of duty as a noble and over-riding ideal faded, weakening as a deterrent the supreme punishment instituted by Bridges for indiscipline, return to Australia in disgrace.

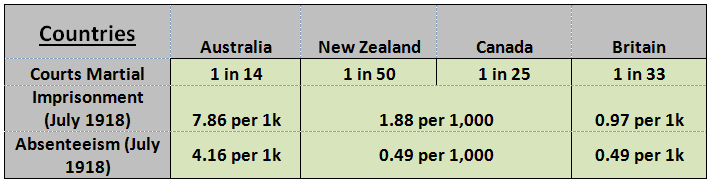

Whereas eleven Australians deserted in the three months before the battles, courts-martial convicted 288 men for it by the end of 1916. Sixteen Australians received death sentences between July and November. With the onset of the harshest winter in forty years, they were joined by fourteen more in December, the highest monthly total of the war.

These figures were a reminder that the jurisdictional question regarding capital punishment for Australian soldiers was still unanswered. On 11 December Birdwood revisited it, venturing to Gen. Rawlinson, of whose Fourth Army I ANZAC was part, that the Australians’ discipline would likely suffer when they realised that a regulation binding other soldiers in the British Army did not apply to them. Rawlinson needed no convincing.

Three Australian deserters had been sentenced to death in the Fourth Army so far that month and 130 of its 182 absence cases were Australian. He told Haig that he would not be responsible for the discipline of the Australians unless the law was immediately altered. Haig strongly supported him. On 3 February, the War Council stressed that the change was essential.

The Australian Government finally responded, seven months after the matter was first raised. The British concerns did not diminish the existing arguments against acquiescence. Provoking public antipathy to the death penalty would adversely affect voluntary recruiting and reignite the passions generated by the conscription campaign at a time when it had held office less than a month. The answer was no.

When the matter resurfaced after the twin battles of Bullecourt in April-May 1917, some Australian commanders joined the British chorus. In the disastrous first battle, the 4th Division suffered the heaviest proportionate losses of an Australian formation in a single action. When it was warned for the attack on the Messines-Wytschaete Ridge in June, after only one month’s rest, desertions from it became acute. Its commanders urged upon Birdwood the amendment of Section 98 so that it could be applied to a few cases.

The commander of the 3rd Division, Maj-Gen Monash, similarly approached Birdwood shortly afterward. Monash had no doubt that the increase in serious crime, especially ‘desertion and the avoidance of battle duties’, was due to the absence of any real deterrent. But the carrying into effect of even one death sentence would cause potential deserters to hesitate, thereby stiffening discipline. Consequently, the Australian government should be urged strongly to withdraw its prohibition on the death penalty. If it rejected this demand, an unequivocal statement that convicted deserters whose sentences were commuted to penal servitude would serve the full term of their punishment, irrespective of any armistice, should be sought.

Birdwood answered Monash as he had the others. Everything that could be done had already been done, not just by himself but by Haig, the Army Council and the Secretary of State for the Colonies, who between them had urged the Australian government ‘much more strongly than he’. But it had told all of them in ‘definite terms’ that the matter would not be reopened. Meanwhile Lt-Gen Godley, the commander of II ANZAC recommended asking the government outright to allow the second of Monash’s options. Penal sentences imposed by courts-martial should be served in full even if the war ended in the meantime.

That compromise did not satisfy Haig. Worried about the deterioration of discipline in the AIF and the effect of the Australian example on the BEF, he visited I ANZAC on 29 July to ask what could be done. Maj-Gen White, its Australian Chief of Staff, re-iterated that the Australian Government would never agree to the shooting of deserters. Unwilling or unable to accept what White had spelt out so clearly, Haig continued to press for the full and urgent application of the British Army Act to Australian troops.

Perhaps realising that full application would make them liable to the death penalty for a range of offences, he promised the most sparing use - in cases ‘where desertion was most deliberate and an example badly needed’.

Birdwood knew that the Australian response would be the same as before but he had to support his chief. He suggested to Senator Pearce, the Australian Defence Minister, that the death penalty should be imposed solely for desertion, and then only if conscription were introduced. Even this dilution was too much. On 20 September Pearce replied that the impact on flagging enlistment would be ‘disastrous’, so much so that the request could not have come at a more inopportune time.

The Australian Government’s decision to leave Section 98 in place came as the Australians joined Haig’s Third Ypres offensive. The effect on discipline was the same as in previous campaigns. Ten Australians were sentenced to death in August, the month before it began. 53 men left the 2nd Division as it went into the line. Courts-martial for absence and desertion peaked in October and sixteen death sentences were passed in September and October, the two months of Australian involvement. On 5 November, in a step reminiscent of Bridges’ measure three years earlier and based on the same exemplary principle, Birdwood asked Pearce to approve the publication in all Australian newspapers and in AIF orders of deserters’ names, towns of enlistment and sentences.

Two days later a second conscription referendum was announced for December. Recruiting in the second half of 1917 had fallen far short of the numbers needed to replace the 38,000 casualties of Third Ypres and cover future wastage. The anti-conscriptionists were not swayed. In a campaign that was more bitter than the first, they increased their majority. The voluntary system remained intact but from now on it was unable remotely to meet the AIF’s needs. Desertions and imprisonments depleted its ranks further, leaving Pearce little choice but to agree to Birdwood’s proposal. It came into effect in January 1918. The government also flirted with the addition of murder to the crimes covered by Section 98 but it withdrew the amendment at the Armistice.

At the same time, AIF attitudes to shell shock softened. In December 1917, Birdwood formally acknowledged that some breakdowns were very different to cases of deliberate desertion to avoid action. He directed that ‘the medical aspect of the case should be carefully gone into before the man is charged with desertion’.

The following May Monash, Birdwood’s successor as commander of the Australian Corps, ordered the withdrawal from the line of long-service men suffering from ‘nerves’. Many were sent to support units. In July, the commander of the 5th Division, Maj-Gen. Hobbs, interviewed seven men convicted of desertion. Finding some of them to be nervous wrecks, ‘more to be pitied than blamed’, he suspended the sentences and instructed commanding officers not merely to read the court records of men found guilty but to see the men themselves.

Though long in coming, this enlightened attitude towards a major cause of desertion helps explain why only two Australians received death sentences in 1918.

Ironically, a number of Australian soldiers could legitimately have been executed that year. By September, their corps had lost almost 50,000 men in six months’ continuous fighting. As recruiting in Australia was down to a trickle, these casualties could not be replaced, reducing some battalions to fewer than 100 men. Eight were disbanded to feed the rest.

The order was a shattering blow for the men concerned and they refused to obey it. In what was considered a ‘strike’ rather than a mutiny at the time, they elected their own leaders, maintained ‘especially strict discipline’ and asked to go into the next battle, the assault on the Hindenburg Line, in their old units. The other battalions sympathised with them, creating a dilemma for Monash. He decreed that the battalions could remain but they would not receive reinforcements. After the battle, the Australian Corps’ last, the battalions disbanded voluntarily.

Another incident could not be disguised as ‘industrial action’. On 21 September, 119 men of the 1st Battalion stood fast when they were ordered back into the line shortly after their relief, protesting that they were being called upon to make good British failures as well as having to fight on their own front. ‘Fatigue mutiny’ or not, these men had committed an offence unequivocally punishable by death under Section 98 for the first time in the war. Aware of the outcry at home that its enforcement would provoke, Monash again took the broader view. All but one of the 119 were convicted of desertion rather than mutiny and sentenced to up to ten years imprisonment on Dartmoor.

The Australian commanders were essentially orthodox disciplinarians. To them desertion was more than a slander against military virtue for the AIF could ill afford to lose men to non-battle causes when it relied on an increasingly fragile voluntary system to replenish its ranks. So they regarded as necessary the death penalty to deter it.

Some of them even dismissed the sensitive and considered way Monash and Hobbs dealt with desertion due to nervous exhaustion in 1918 as ‘merely likely to store up future trouble’. The collective Australian opinion that the hardened deserter saw a long prison sentence as merely a safer alternative to the trenches was advanced by Field-Marshals Allenby and Plumer when they publicly opposed the abolition of the death penalty in the British Army after the war.

For his part, the Australian soldier was not sympathetic to deserters. The men of the 1st Battalion who attacked on 21 September never forgave their comrades who did not.

But condemning them to death was something else again.

The reading out to Australians on parade of reports on executions evoked only a sullen sympathy and a fierce pride that their own people had refused this instrument to its rulers.

The strength of popular feeling ranged against capital punishment in the AIF made Section 98 impregnable. So there were no Australian ‘examples’. The AIF remained a volunteer army that possessed alone among the armies ‘the privilege of facing death without a death penalty’.

Dr. Peter A. Pedersen

A graduate of the Royal Military College Duntroon and the Australian Command and Staff College, Dr Peter Pedersen commanded 5th/7th Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment after a secondment to the Australian Prime Minister's Office as a political/strategic analyst. His many publications include books on General Sir John Monash and the Gallipoli Campaign. Dr Pedersen guided the then Prime Ministers Hawke and Thatcher around the Gallipoli Peninsula during the 75th Anniversary Commemoration in 1990 and has led battlefield tours throughout the world. |