You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Footprint of Mussolini - TL

And so with theatric coups the UAR felt for good into pieces. And indeed Pan-arabism as well - ironically the opposite declarations of Nasser and Aflaq proved that it was a facade all along.

At least the Italians proved wise enough to send Libyian and Somali Muslim troops in Arabia. Probably wouldn't change much if there were Christian troops as well at this point, with Arabs dying like flies those terrible days.

Aden... may be a sore spot in the British-Italian relations. Considering also the British troops in Lebanon and Cyprus, the long Italian-British alliance would likely come to end. With the USSR powerless, West and South Europe may end soon toward at odds towards each other over regional conflicts to expand their own influence across the world.

At least the Italians proved wise enough to send Libyian and Somali Muslim troops in Arabia. Probably wouldn't change much if there were Christian troops as well at this point, with Arabs dying like flies those terrible days.

Aden... may be a sore spot in the British-Italian relations. Considering also the British troops in Lebanon and Cyprus, the long Italian-British alliance would likely come to end. With the USSR powerless, West and South Europe may end soon toward at odds towards each other over regional conflicts to expand their own influence across the world.

With the added complication that France also used nukes.I guess the seeds of the split between democracy and fascism have been sown.

If Britain and the other Democracies tilt too fast and too far against colonialism then France might side with the RA in the future. Not go Fascist mind you, just side with them against the Democracies despide being one themselves, in the diplomatic arena with all the implications that has for trade and security arrangements, because they consider doing so in their national interest.

Same as Finland in WW2.

I wouldn’t say isolation, since they provided material and moral support to Israel and Europe during the Arabian War. Rather, I think they’re taking a moment to catch their collective breath, rest up and get rady for the final showdown with Communism that seems to be looming over the world like some bird of ill-omen.Welcome back to isolation, USA.

Peronist style public commitments to workers benefits, support for unions, and anti poverty programmes seem to have had a long life in attracting this sort of support in Argentina.Big spending projects to get people back to work, welfare state, and nationalising a few key industries.

but only mordor is twinned with SwindonVast empire with legion of minions, running on pure evil with only numbers and ferocity so terrifying it unites every traditional enemy and pacifist under the sun?

Two peas in a pod.

Bookmark1995

Banned

Peronist style public commitments to workers benefits, support for unions, and anti poverty programmes seem to have had a long life in attracting this sort of support in Argentina.

Peronism, as I've read, seems completely...bonkers.

Peronism seems to be "make me seem like a man of the people while coddling the elite."

You've had Peronists who are socialists and Peronists who were neoliberals. All of them have caused the economic chaos that continues to plague Argentina.

Deleted member 109224

If Britain loses Yemen, I think they'll put extra effort into Kuwait, UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman. They're going to be scrambling.

Restore the Sultan, give Kuwait something resembling pre-Uqair boundaries, get all that sweet sweet oil for BP, and put Muscat back under the British thumb while they're at it to secure the southern coast in and out of the gulf. Use the oil money to restore the glory of British Empire, etc etc.

Israel going down to Duba seems plausible since racing down the Red Sea Coast was mentioned, but it's also possible that they settle for something a bit smaller.

The rest of Arabia seems like an open question to me. The Italians (via Muslim Italian forces) and Turks have taken Mecca and Medina and the Turks have been promised control of the cities, but I'm not quite sure what that means. The Turks are the overseers of holy sights in Jerusalem too, right? Are Mecca and Medina Turkish-run exclaves? Will Turkey get direct control over the Hijaz? Both of those, but especially the latter, seem troublesome.

Perhaps the Hashemites could be brought back to control the Saudi Arabian rump. Alternatively there's the Rashidis. Or the Hashemites get Hijaz and Rashidis get Najd.

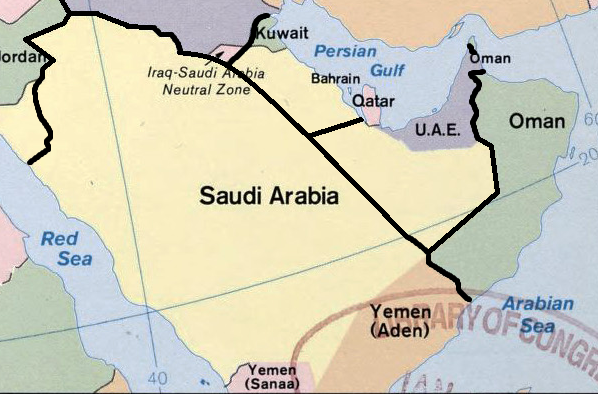

Then there's Yemen. Maybe Yemen gobbles up the whole of rump Saudi Arabia. The Yemeni King wants Greater Yemen - and that includes parts of Saudi Arabia (Najran, Asir, and Jazan). The 20th Parallel shown on the map below actually sort of works for that. But if there are not other options, why not just give the remainder of Saudi Arabia to the Yemenis? The potential religious-sectarian issues (Shia controlling Mecca and Medina) would already be resolved by the Turks controlling the cities.

Also noteworthy is that great Yemen includes the Dhofar province of Oman.

Restore the Sultan, give Kuwait something resembling pre-Uqair boundaries, get all that sweet sweet oil for BP, and put Muscat back under the British thumb while they're at it to secure the southern coast in and out of the gulf. Use the oil money to restore the glory of British Empire, etc etc.

Israel going down to Duba seems plausible since racing down the Red Sea Coast was mentioned, but it's also possible that they settle for something a bit smaller.

The rest of Arabia seems like an open question to me. The Italians (via Muslim Italian forces) and Turks have taken Mecca and Medina and the Turks have been promised control of the cities, but I'm not quite sure what that means. The Turks are the overseers of holy sights in Jerusalem too, right? Are Mecca and Medina Turkish-run exclaves? Will Turkey get direct control over the Hijaz? Both of those, but especially the latter, seem troublesome.

Perhaps the Hashemites could be brought back to control the Saudi Arabian rump. Alternatively there's the Rashidis. Or the Hashemites get Hijaz and Rashidis get Najd.

Then there's Yemen. Maybe Yemen gobbles up the whole of rump Saudi Arabia. The Yemeni King wants Greater Yemen - and that includes parts of Saudi Arabia (Najran, Asir, and Jazan). The 20th Parallel shown on the map below actually sort of works for that. But if there are not other options, why not just give the remainder of Saudi Arabia to the Yemenis? The potential religious-sectarian issues (Shia controlling Mecca and Medina) would already be resolved by the Turks controlling the cities.

Also noteworthy is that great Yemen includes the Dhofar province of Oman.

This literally has to be some of the darkest shit I have ever read.

Have you read the What Madness is This Redux? Or For All Time? Or Fear, Loathing, and Gumbo and its sequel?

That being said, yeah, this is bad...

Probably. 50KT isn't insurmountable.

From Cairo, Capital of Arab Egypt to Mussolinia, Capital of the Italian Province of Aegyptus

Now it looks so perfect

From Cairo, Capital of Arab Egypt to Mussolinia, Capital of the Italian Province of Aegyptus

Now it looks so perfect

Nah, if they're going for maximum Roman, I think they'll make Alexandria the capital instead.

Israel going down to Duba seems plausible since racing down the Red Sea Coast was mentioned, but it's also possible that they settle for something a bit smaller.

Frankly, some borders are less important than others. Israel wants the rest of the Gulf of Aqaba coast, *nobody* (including Israel) wants the Israels to have Mecca/Medina and none of the areas that are up for debate have oil.

Israel will probably take precisely that area and no more in that direction. They'll have their hands more than full, however, in a large portion of southern Syria which, whether they actually want it or not, will be under their occupation almost by default, at least temporarily.Frankly, some borders are less important than others. Israel wants the rest of the Gulf of Aqaba coast, *nobody* (including Israel) wants the Israels to have Mecca/Medina and none of the areas that are up for debate have oil.

I specify temporarily because Israel might chose not keep parts of it ultimately as their territory. I'd expect however that they'd keep the area that used to include Damascus at least.

Maybe a Coptic ruled Alexandria or "Coptic" zone will come into effect in Egypt. Looking forward to what comes next

Yup. Essentially Israel's new borders will be of three types:Israel will probably take precisely that area and no more in that direction. They'll have their hands more than full, however, in a large portion of southern Syria which, whether they actually want it or not, will be under their occupation almost by default, at least temporarily.

I specify temporarily because Israel might chose not keep parts of it ultimately as their territory. I'd expect however that they'd keep the area that used to include Damascus at least.

1)Southwest: the Canal, pretty easy to defend, and the Europeans will help.

2)North/Northeast: Populated on the other side

3)South/Southeast:Empty on the other side.

Dolan

Banned

That would be the best for International Public Relations, returning Egypt to their rightful Aegyptian people while c̶o̶m̶m̶i̶t̶ ̶m̶a̶s̶s̶ ̶m̶u̶r̶d̶e̶r̶ ̶a̶n̶d̶ ̶e̶x̶p̶u̶l̶s̶i̶o̶n̶ rearrange population transfer of Egyptian Arabs so they would be the problem for Turkey-owned Holy Cities.Maybe a Coptic ruled Alexandria or "Coptic" zone will come into effect in Egypt. Looking forward to what comes next

If Mussolini did endorse the events in Aden, he is playing an interesting game. On the one hand it kills much of his goodwill with Britain. But on the other it could be a move to show 'third world' countries that the RA will aid its friends in realizing their ambitions; even being willing to support them to a degree against the great powers.

So Mussolini might be shifting his approach from the great powers of Europe to the emerging nations? After all he probably figures as long as the USSR is in play the Western democracies will go only so far against him and no further.

Maybe Egypt could be partitioned? A Coptic minority rule state locked in the RA orbit and an Arab state that is independent but has been slapped with neutrality and military limitations? Because Mussolini might want an annexation, but he can be checked by his government as we saw Post War with Umberto being crowned.

So Mussolini might be shifting his approach from the great powers of Europe to the emerging nations? After all he probably figures as long as the USSR is in play the Western democracies will go only so far against him and no further.

Maybe Egypt could be partitioned? A Coptic minority rule state locked in the RA orbit and an Arab state that is independent but has been slapped with neutrality and military limitations? Because Mussolini might want an annexation, but he can be checked by his government as we saw Post War with Umberto being crowned.

Last edited:

Intermission- Thailand and Indo-China

Hello to all, this time we will see how the tides of history changed in the Asian South-East and more precisely on Thailand and Vietnam... with the usual supervision of Sorairo, enjoy!

Extract from 'The Radical Change of the Asian Far East after WW2, Volume Five: the Indochinese Region' by Johnathon Brando

Of all the nations which sided with the Dual Pact during World War 2, Thailand was likely the nation which paid the lightest cost of the defeat. From 1935 to 1945, the Siamese military ruled the country, taking advantage of the absence of the new King Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII) who was underage and studying in Switzerland. Among those military officers emerged the figure of Plaek Phibunsongkrahm, who became first minister in 1938 and would soon implement a full dictatorship, taking great inspiration from Mussolini. Phibunsongkrahm was naturally an ardent nationalist and he was against the Anglo-French condominium in the Asian South East, albeit he strived for his country to become modern and adopting western costumes; but he wasn’t anti-Italian, from the moment Italian influence in the region was not existent, and therefore more than willing to entertain commercial relations with Rome, especially on the communication side. The Instituto Luce sold several documentaries and movies in Thailand at the time, a tendency which would only improve after the war, to the point later RAI would open its first foreign Far Eastern Asian offices in Bangkok. Phibunsongkrahm took great inspiration from Italian propaganda, under the guidance of Luang Wichitwathakan, to create his own consensus machine and rule over rural policies and military renovation.

Despite those good Italian-Thai relations, Phibunsongkrahm looked for an alliance with Japan, interestingly more in an anti-Chinese role than anti-French and British, as the dictator and Wichitwathakan wanted to eradicate Chinese commercial and above all cultural presence from their country, even with violent ways (the latter arrived to compare the Chinese in Thailand worse than the Jews in Germany). Nonetheless, in 1940, Phibunsongkrahm wouldn’t hesitate in invading and annexing southern Cambodia with Japanese consensus after the fall of France. At the end of 1941, despite doubts within his administration, he would allow the Japanese troops to enter in his country officially to secure Thailand from British aggression following the attack on Pearl Harbour, despite in truth the same Japanese wanted to be sure to control the nation also to stage the invasion of India.

Now, Phibunsongkrahm believed in the Japanese victory and allowed the occupation in the belief Thailand would play a relevant role in the Japanese Great Co-Prosperity sphere dream, but between 1942 and 1943 he would get soon disabused, between the first Japanese defeats and the air raids on Bangkok. At the start of 1944, he and the Japanese would be no less shocked to hear of Germany’s foolish invasion of Italy. Phibunsongkrahm would soon find an opening – while Italy reluctantly declared war to the Japanese, it didn’t make a similar declaration upon Thailand. In fact, most of the Allies ignored Phibunsongkrahm’s war declarations of 1941, mostly because they considered Thailand a Japanese puppet at the point; while it was surely humiliating, now gave the Thai dictator an angle to attempt a negotiation with the Allies through Italy.

The Italians weren’t hostile towards Thailand as they weren’t towards Japan as well – Italy declared war upon Japan upon British pressure and appeasement towards the USA. And from what Mussolini got to know over Phibunsongkrahm, he was quite sympathetic to him, as he was for every dictator who took open inspiration from himself (the Thai leader even introduced the Roman salute, even if wasn’t mandatory). In early 1944, Mussolini and Ciano were inclined to believe the Pacific war would have ended over a compromise peace and even if Japan would concede defeat, it wouldn’t necessarily be over an unconditional surrender, therefore giving the Japanese and also the Thai sufficient autonomy and freedom of action and for Italy, to establish new pacts and alliances after the war, believing that the Allies won’t have carried fully the Cairo declarations. However, it was soon clear that the Americans won’t have budged from the total Japanese surrender, and after the visit of Chiang in Western Europe, Mussolini would have implicitly approved the Cairo declarations, as would the French shortly after.

But it was also soon clear that the Allies would eventually treat Japan and Thailand differently, in short acting more lenient towards the latter. Phibunsongkrahm was discretely informed from the embassy in Rome over such intentions, but he knew that he was on thin ice, in part from gradual loss of internal support, in part over the Japanese troops present in Thailand. So he was rather powerless in attempting a negotiation that would have bailed out Thailand from the war. However, his decision to move the capital from Bangkok to a more northern position, building a new city from scratch, caused high discontent between his own supporters, forcing him to resign as first minister, albeit holding still the control of the armed forces. Whether it was a calculated move to put himself in a not political role in the moment Thailand would have surrendered or not is still up to debate.

Thailand would have been spared from the devastation of an Allied invasion in 1945, however. While the British Indian forces would have managed to free Burma but taking most of the year to do it, the expeditionary Western European force (British, Italians and French) would have landed in Malaya and freeing Singapore, then parts of the East Indies to proceed towards French Indochina, from where they would split (the British focusing on freeing the rest of the Indonesian islands, the French to clean up Indochina from the rising Communist insurgence and the Italians assisting the Chinese Nationalists in invading Taiwan). Thailand would end encircled, but it was at this point August – the nuclear bombs and the fall of Korea forced Japan to surrender, and so the Japanese forces in Thailand. The “Free Thai” opposition movement would manage to remove the military government, and lead the country towards the end of the war.

Thailand would agree in the peace deal to turn back all the territories occupied and embrace a democratic system, but the military establishment which ruled the country wasn’t persecuted – Phibunsongkrahm and Wichitwathakan would be put on trial only for military crimes and getting full absolution, the first declaring to retire from public life and the second focusing on literacy and theatre. Thailand, readopting again the name Siam, however didn’t become a stable country. In fact, as Rama VIII was finally able to return in Siam, he would die in the June of 1946 in mysterious circumstances, creating tensions across the country – as the “Free Thai” movement collapsed soon into factions, part of them accused the seating first minister Pridi Banomyong to be behind the death of Rama VIII. Now, Banomyong was a prestigious and capable politician, but he had Chinese roots and was backed by the British, and as his political enemies reminded those facts to the population, they contributed to his fall. Yet, the stillborn Siamese democracy was already in tatters and a political stall would soon emerge.

Phibunsongkrahm saw the conditions for a return to power, but he was aware he needed a powerful foreign patron – because he felt at the time Thailand or any of the Indochinese nations hardly could have stand alone against a resurgent China, regardless of who would have emerged between Mao and Chiang on the top. Excluded the British and the French, there were the Americans and the Italians: but the former’s reputation in the Far East was mostly sullied after Potsdam and the Wallace administration was considered untrustworthy by Asian who were not communist nationalists. Besides in Washington the Far Eastern foreign policy was completely wrecked at the time: the infamous “China Lobby”, totally incensed against Wallace, would have attempted a reconciliation with Chiang but at the same time, being oriented to support a stable Thailand, even at cost to reallow Phibunsongkrahm to return into power, in case the worst will happen – Mao winning the Chinese civil war. But Wallace wasn’t interested at all in commit further American interference in the region, considering that the United States were also handling the occupation of Japan and the final independence process of the Philippines, nor was willing to compromise with the Chinese lobby at all. In doing so, American influence in the Far East wouldn’t go beyond Japan, and even if the Patton presidency restored some trust with the Chinese nationalists, said influence would remain limited for decades.

For Phibunsongkrahm, Italian support was the most logical choice. Italy emerged as an effective great power, wasn’t invasive in internal matters like the British and the French, and Mussolini was very respected by him while Fascism was still more appealing rather than the struggling democratic movement. Taking agreements with the Italians, Phibunsongkrahm wouldn’t hesitate in the November of 1947 to launch a coup, imposing a political ally while he reasserted himself as commander of the armed forces. As such government struggled to appease the military, Phibunsongkrahm would retake the premiership in the April of 1948 and de facto restoring his dictatorship. He wouldn’t suspend the new constitution or the recent democratic institutions, but he would cage them by creating a Thai Fascist party while concentrating powers on his figure and steering the nation towards a new authoritarian direction, while adopting the name Thailand for good.

With Italian subsides and technical expertise, Thailand will officially join the Roman Alliance in the January of 1950, above all to reaffirm the nation’s independence from Anglo-French and also Nationalist Chinese influence. Chiang, which fortunes started to turn high again thanks to Italian support, accepted as fait accompli Italian influence over Thailand, agreeing silently to not exercise further economic interests in the country; the British, which power in the entire region went drastically reduced with Indian independence and dealing with its aftermath, but still holding positions from Ceylon to Singapore, through Burma, while concerned over Malaya, was in no position to contest such alliance. But the French, who were still rebuilding their authority in Eastern Indochina, were jaded over the growing Italian presence in the South-East Asian region, historically an Anglo-French condominium. But as the Patton administration would acknowledge Phibunsongkrahm’s regime as well, Paris reluctantly went for it, forcing De Gaulle to revisit his own Indochinese policy, giving Bao Dai a diplomatic opening over the final status of Vietnam.

Thailand would benefit from the Chinese war, becoming an important supply node for Italian and Roman alliance forces on the road to South China, where the trade balance started to shift more favorably to Bangkok. Phibunsongkrahm would complete his program of nationalizing Chinese assets while reducing their own cultural influence as well, as Wichitwathakan’s propaganda machine would return soon active. Thailand would also start to grooming relations with other Italian allies, like Israel, agreeing to send a small military support during the Second Arabian War, which would give Phibunsongkrahm the occasion to start a new wave of persecutions against the Muslim communities in the country (despite there being many Muslims fighting on the Italian side), forcing conversions or expulsions towards Malaya in order to break them for good. Given the heated nature of the conflict, only the Soviet Union would issue a condemnation of Thailand’s actions, which in the geopolitical environment of 1956 was more of a benefit than a hindrance. Regardless, the aftershock of the Second Arabian War would in a way or another invest the Asian South-East as well. Between British and French growing weariness in the region, growing tensions in Indonesia, not counting the Chinese split, Japanese still in a state of weakness, and initial Korean approaches in the region, Thailand was slowly rearming and starting to pursue dreams of hegemony over the area. However, they were soon to come face to face with a powerful enemy.

When at the start of 1945 the joint force of British, French and Italians freed Singapore and recovered most of Malaya, reopening to the Allies access to the South Chinese Sea, the Japanese forces in French Indochina on March 9th eradicated the entire local colonial administration, included the Sureté, the head of the political police force. As the Japanese would gradually relocate to safer Thailand, the Indochinese nationalists started to take control of the region. Bao Dai, the Emperor of Annam (Chinese term for Vietnam) tried to coalesce all the Vietnamese under his rule and build the basis of an united country, but was hindered by the growing opposition of the Communists of Nguyen Ai Quoc, who assumed the battle name of Ho Chi Min, and was able to coalesce a strong enough independence Front (the Viet Minh), preparing a general insurrection for the late Summer of the same year.

But around May, the French would land in Indo-China, retaking Saigon. Ho Chi Min, despite knowing the Viet Minh wasn’t fully ready, decided to act before the French would retake all of Vietnam. While the Viet Minh managed to take Hanoi and the Tonkin region, they were too fatigued to proceed towards Annam proper, where Bao Dai, despite his own difficulties, had still some support. After pondering whether to abdicate in exchange for the Viet Minh to retain a relevant role in an unified Vietnamese government, he decided to turn to the French and negotiate with them. Now, as in Paris they realized ahead of time that restoring the old colonial system would have been impossible, but also being determined to still be the arbiters of the region, in the end agreed to accept Bao Dai’s offer of surrender while allowing him to remain Emperor of Annam, thus the French to occupy more easily Central Vietnam.

With Bao Dai siding with the French, the Viet Minh offensive halted, leaving Ho Chi Min and the communist leadership on a crossroad. While the Viet Minh would publicly accuse the Emperor of having sold out Vietnam to Paris, nonetheless it barely controlled only the North. As the French would soon start to press them to lower down their arms and re-allow their jurisdiction on the Tonkin, Ho Chi Min would decide for an act of force, declaring in Hanoi the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and acting as provisional and legitimate government for all of Vietnam. Ho Chi Min believed that the USSR and the US would have supported him, the first for ideological brotherhood and the second because it appeared that Wallace was sympathetic towards anti-colonialist movements and independence groups.

But De Gaulle at Potsdam obtained from all the Allies, USA and USSR included, the guarantee that French rule or at least interest in Indochina would be fully restored and respected. Wallace, who already annoyed the British and Italians, was convinced to not annoy the French as well, while Stalin was disinterested over Indochina. Though starting to put the USSR’s foreign policy on an anti-British and anti-Italian bent, he wasn’t intentioned to anger the French in the hope to break the Western European front. While this never really happened, Stalin’s strategy wasn’t totally unsound, as until the Second Arabian War, there were significant tensions between France and Italy (over Tunisia, Syria, and in particular over Thailand) and France strongly opposed the British plans over West Germany, though never at the point of a total rupture. France had international legality to restore its own order in Indochina. Paris wouldn’t acknowledge the DRV, the DRV refused to bow, so open conflict would be inevitable. But France was unable to commence operations in the North until the March of the next year. In fact in Cambodia and Laos, the Japanese continued to fight, while British and Italians would focus over other campaigns in the area.

The Viet Minh soon discovered themselves isolated diplomatically. Not even the Chinese Nationalists would help them – Chiang had his own difficulties, and incensed against the Americans since Potsdam, would turn towards Western European support, renouncing influence in Indochina in exchange of any kind of assistance France may offer. Effectively De Gaulle would give the Kuomintang proper support and, when the fight in Indochina intertwined with the Chinese War, would send additional divisions to join the South Chinese coalition. During 1946, the French, after landing in Haiphong, being subjected to a hard bombardment and then freeing Hanoi after a strenuous city guerrilla battle, would push the Viet Minh towards the north-eastern mountains. Despite growing difficulties, Ho Chi Min would manage to keep the front united and even gain ground in Laos, where the French were more disadvantaged in terms of logistic. The occupation of most of Tonkin would cause further resentment with the Vietnamese, with looming protests and riots. Nonetheless, France would proceed to organize the region into a loose federation between Cambodia, Laos, Cochinchina, Annam and Tonkin, where Paris would have retained control on several matters, from currency to diplomatic and military affairs: but Bao Dai, who progressively aligned with the Vietnamese right-nationalist opposition, would state that only an united Vietnam could make such federation project work.

Between 1948 and 1949, as the Chinese communists seemed on the verge of victory, hundred of thousand “volunteers” crossed the border with Vietnam, assisting an ailing Viet Minh, forcing the French to lose positions in the North. De Gaulle would be forced to commit more forces in Indochina, an action that started to erode consensus around him. Bao Dai and his political allies started to capitalize over the growing French weariness and commitment failure over Indochina. Agreeing to open a new negotiation round in Paris, he would convince De Gaulle of the necessity of a united Vietnam to guarantee French interests. Obtaining from France the guarantee over Vietnamese unity, he would manage to declare at home the union between Cochinchina and Annam and Annamite administration over Tonkin, moving the capital to Saigon, and proclaiming the change of the name of the Empire of Annam to Vietnam.

As Bao Dai would start to coalesce more internal favour, the Viet Minh would start to collapse around 1951. The North Chinese support would be forced to retreat when the Coalition managed to take Yunnan, while the Viet Minh offensive in Tonkin that year failed and the French would manage to kill in a lucky shot Giap, the chief commander of the North Vietnamese army. With the death of Giap, Ho Chi Min struggled to coordinate the military effort – and after a failed attempt to siege the recently established French base of Dien Pien Bhu, he started to seek a diplomatic surrender – but he placed as condition he would surrender to Bao Dai’s nationalist supporters rather than the French.

Though Bao Dai certainly was no communist sympathizer, he knew well the population were generally Anti-French; in the Paris talks, as he managed to guarantee Vietnamese unity, he gained support and prestige at home, but still the Indochinese Federation wasn’t well seen. By taking over the negotiations with the Viet Minh, he would prove that he wasn’t a puppet of Paris and also would have started to reconcile all Vietnam under his guidance. De Gaulle and his government weren’t fully happy with this, but the French public opinion was growing tired of almost 12 years of war, whenever on their soil or aboard, and would agree on peace talks between the Viet Minh and the Empire of Vietnam. While Ho Chi Min and the Viet Minh leadership would accept surrender and dissolve the Communist Party, and disarm themselves, they would receive lenient punishments as house arrests and timed interdictions from political activities in the entire Federation; while obtaining that the Suretè wouldn’t be restored in any form and guaranteeing sufficient political freedom of protest and free press.

Thus with the Viet Minh starting to disarm, and the French completing the recovery of Indochina when the last bastions of resistance in Laos fell and the war in China turned against the Communists for good, the final decision came. On March 1st 1952 in Saigon, the protocols of the birth of the Indochinese-French Federation, formed by the Kingdoms of Laos and Cambodia, and the Empire of Vietnam were signed. These nations were all declared formally independent, but overseen by a French presidency, having authority in currency, diplomatic, military and cultural (as use of French as shared language) matters. Though French interests in the region would finally be fully restored, the Federation was still fruit of a compromise that would not satisfy fully everyone. Not the Vietnamese, nor the Cambodians, the Laotians and even the French – certainly not the socialists nor the communists. The Second Arabian War would further stress what was a weak bond between the four nations. In late 1952, Vietnam would oversee its first democratic elections, which brought into victory the nationalist right. The Emperor would name Ngo Dihn Diem, leader of the Vietnamese right first minister not long before after. Diem was likewise anti-French, and intimately hoped to get support from Italy or the US to get the nation completely out of French grip. However, both Patton and Mussolini, for different reasons, didn’t want to break the new status quo in the Far East.

Therefore, Diem and Bao Dai would have to wait for better times before attempting to slip out from Paris’s radar, focusing over the reconstruction and the recovery of Vietnam. They wouldn’t have to wait long, as the French would soon have to fight over the aftermath effects of the Second Arabian War, and decolonization in Asia was reaching its conclusion without a clear great power able to exercise an hegemonic influence. Tensions between the nations of the South East and the Far East would progressively start to boil. Not too long after the cataclysmic effects of the Second Arabian War, and the newfound rivalries that emerged from the subsequent peace, something would happen in Southern Asia that would change the geo-political picture not just in Asia, but the whole world.

Extract from 'The Radical Change of the Asian Far East after WW2, Volume Five: the Indochinese Region' by Johnathon Brando

Of all the nations which sided with the Dual Pact during World War 2, Thailand was likely the nation which paid the lightest cost of the defeat. From 1935 to 1945, the Siamese military ruled the country, taking advantage of the absence of the new King Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII) who was underage and studying in Switzerland. Among those military officers emerged the figure of Plaek Phibunsongkrahm, who became first minister in 1938 and would soon implement a full dictatorship, taking great inspiration from Mussolini. Phibunsongkrahm was naturally an ardent nationalist and he was against the Anglo-French condominium in the Asian South East, albeit he strived for his country to become modern and adopting western costumes; but he wasn’t anti-Italian, from the moment Italian influence in the region was not existent, and therefore more than willing to entertain commercial relations with Rome, especially on the communication side. The Instituto Luce sold several documentaries and movies in Thailand at the time, a tendency which would only improve after the war, to the point later RAI would open its first foreign Far Eastern Asian offices in Bangkok. Phibunsongkrahm took great inspiration from Italian propaganda, under the guidance of Luang Wichitwathakan, to create his own consensus machine and rule over rural policies and military renovation.

Despite those good Italian-Thai relations, Phibunsongkrahm looked for an alliance with Japan, interestingly more in an anti-Chinese role than anti-French and British, as the dictator and Wichitwathakan wanted to eradicate Chinese commercial and above all cultural presence from their country, even with violent ways (the latter arrived to compare the Chinese in Thailand worse than the Jews in Germany). Nonetheless, in 1940, Phibunsongkrahm wouldn’t hesitate in invading and annexing southern Cambodia with Japanese consensus after the fall of France. At the end of 1941, despite doubts within his administration, he would allow the Japanese troops to enter in his country officially to secure Thailand from British aggression following the attack on Pearl Harbour, despite in truth the same Japanese wanted to be sure to control the nation also to stage the invasion of India.

Now, Phibunsongkrahm believed in the Japanese victory and allowed the occupation in the belief Thailand would play a relevant role in the Japanese Great Co-Prosperity sphere dream, but between 1942 and 1943 he would get soon disabused, between the first Japanese defeats and the air raids on Bangkok. At the start of 1944, he and the Japanese would be no less shocked to hear of Germany’s foolish invasion of Italy. Phibunsongkrahm would soon find an opening – while Italy reluctantly declared war to the Japanese, it didn’t make a similar declaration upon Thailand. In fact, most of the Allies ignored Phibunsongkrahm’s war declarations of 1941, mostly because they considered Thailand a Japanese puppet at the point; while it was surely humiliating, now gave the Thai dictator an angle to attempt a negotiation with the Allies through Italy.

The Italians weren’t hostile towards Thailand as they weren’t towards Japan as well – Italy declared war upon Japan upon British pressure and appeasement towards the USA. And from what Mussolini got to know over Phibunsongkrahm, he was quite sympathetic to him, as he was for every dictator who took open inspiration from himself (the Thai leader even introduced the Roman salute, even if wasn’t mandatory). In early 1944, Mussolini and Ciano were inclined to believe the Pacific war would have ended over a compromise peace and even if Japan would concede defeat, it wouldn’t necessarily be over an unconditional surrender, therefore giving the Japanese and also the Thai sufficient autonomy and freedom of action and for Italy, to establish new pacts and alliances after the war, believing that the Allies won’t have carried fully the Cairo declarations. However, it was soon clear that the Americans won’t have budged from the total Japanese surrender, and after the visit of Chiang in Western Europe, Mussolini would have implicitly approved the Cairo declarations, as would the French shortly after.

But it was also soon clear that the Allies would eventually treat Japan and Thailand differently, in short acting more lenient towards the latter. Phibunsongkrahm was discretely informed from the embassy in Rome over such intentions, but he knew that he was on thin ice, in part from gradual loss of internal support, in part over the Japanese troops present in Thailand. So he was rather powerless in attempting a negotiation that would have bailed out Thailand from the war. However, his decision to move the capital from Bangkok to a more northern position, building a new city from scratch, caused high discontent between his own supporters, forcing him to resign as first minister, albeit holding still the control of the armed forces. Whether it was a calculated move to put himself in a not political role in the moment Thailand would have surrendered or not is still up to debate.

Thailand would have been spared from the devastation of an Allied invasion in 1945, however. While the British Indian forces would have managed to free Burma but taking most of the year to do it, the expeditionary Western European force (British, Italians and French) would have landed in Malaya and freeing Singapore, then parts of the East Indies to proceed towards French Indochina, from where they would split (the British focusing on freeing the rest of the Indonesian islands, the French to clean up Indochina from the rising Communist insurgence and the Italians assisting the Chinese Nationalists in invading Taiwan). Thailand would end encircled, but it was at this point August – the nuclear bombs and the fall of Korea forced Japan to surrender, and so the Japanese forces in Thailand. The “Free Thai” opposition movement would manage to remove the military government, and lead the country towards the end of the war.

Thailand would agree in the peace deal to turn back all the territories occupied and embrace a democratic system, but the military establishment which ruled the country wasn’t persecuted – Phibunsongkrahm and Wichitwathakan would be put on trial only for military crimes and getting full absolution, the first declaring to retire from public life and the second focusing on literacy and theatre. Thailand, readopting again the name Siam, however didn’t become a stable country. In fact, as Rama VIII was finally able to return in Siam, he would die in the June of 1946 in mysterious circumstances, creating tensions across the country – as the “Free Thai” movement collapsed soon into factions, part of them accused the seating first minister Pridi Banomyong to be behind the death of Rama VIII. Now, Banomyong was a prestigious and capable politician, but he had Chinese roots and was backed by the British, and as his political enemies reminded those facts to the population, they contributed to his fall. Yet, the stillborn Siamese democracy was already in tatters and a political stall would soon emerge.

Phibunsongkrahm saw the conditions for a return to power, but he was aware he needed a powerful foreign patron – because he felt at the time Thailand or any of the Indochinese nations hardly could have stand alone against a resurgent China, regardless of who would have emerged between Mao and Chiang on the top. Excluded the British and the French, there were the Americans and the Italians: but the former’s reputation in the Far East was mostly sullied after Potsdam and the Wallace administration was considered untrustworthy by Asian who were not communist nationalists. Besides in Washington the Far Eastern foreign policy was completely wrecked at the time: the infamous “China Lobby”, totally incensed against Wallace, would have attempted a reconciliation with Chiang but at the same time, being oriented to support a stable Thailand, even at cost to reallow Phibunsongkrahm to return into power, in case the worst will happen – Mao winning the Chinese civil war. But Wallace wasn’t interested at all in commit further American interference in the region, considering that the United States were also handling the occupation of Japan and the final independence process of the Philippines, nor was willing to compromise with the Chinese lobby at all. In doing so, American influence in the Far East wouldn’t go beyond Japan, and even if the Patton presidency restored some trust with the Chinese nationalists, said influence would remain limited for decades.

For Phibunsongkrahm, Italian support was the most logical choice. Italy emerged as an effective great power, wasn’t invasive in internal matters like the British and the French, and Mussolini was very respected by him while Fascism was still more appealing rather than the struggling democratic movement. Taking agreements with the Italians, Phibunsongkrahm wouldn’t hesitate in the November of 1947 to launch a coup, imposing a political ally while he reasserted himself as commander of the armed forces. As such government struggled to appease the military, Phibunsongkrahm would retake the premiership in the April of 1948 and de facto restoring his dictatorship. He wouldn’t suspend the new constitution or the recent democratic institutions, but he would cage them by creating a Thai Fascist party while concentrating powers on his figure and steering the nation towards a new authoritarian direction, while adopting the name Thailand for good.

With Italian subsides and technical expertise, Thailand will officially join the Roman Alliance in the January of 1950, above all to reaffirm the nation’s independence from Anglo-French and also Nationalist Chinese influence. Chiang, which fortunes started to turn high again thanks to Italian support, accepted as fait accompli Italian influence over Thailand, agreeing silently to not exercise further economic interests in the country; the British, which power in the entire region went drastically reduced with Indian independence and dealing with its aftermath, but still holding positions from Ceylon to Singapore, through Burma, while concerned over Malaya, was in no position to contest such alliance. But the French, who were still rebuilding their authority in Eastern Indochina, were jaded over the growing Italian presence in the South-East Asian region, historically an Anglo-French condominium. But as the Patton administration would acknowledge Phibunsongkrahm’s regime as well, Paris reluctantly went for it, forcing De Gaulle to revisit his own Indochinese policy, giving Bao Dai a diplomatic opening over the final status of Vietnam.

Thailand would benefit from the Chinese war, becoming an important supply node for Italian and Roman alliance forces on the road to South China, where the trade balance started to shift more favorably to Bangkok. Phibunsongkrahm would complete his program of nationalizing Chinese assets while reducing their own cultural influence as well, as Wichitwathakan’s propaganda machine would return soon active. Thailand would also start to grooming relations with other Italian allies, like Israel, agreeing to send a small military support during the Second Arabian War, which would give Phibunsongkrahm the occasion to start a new wave of persecutions against the Muslim communities in the country (despite there being many Muslims fighting on the Italian side), forcing conversions or expulsions towards Malaya in order to break them for good. Given the heated nature of the conflict, only the Soviet Union would issue a condemnation of Thailand’s actions, which in the geopolitical environment of 1956 was more of a benefit than a hindrance. Regardless, the aftershock of the Second Arabian War would in a way or another invest the Asian South-East as well. Between British and French growing weariness in the region, growing tensions in Indonesia, not counting the Chinese split, Japanese still in a state of weakness, and initial Korean approaches in the region, Thailand was slowly rearming and starting to pursue dreams of hegemony over the area. However, they were soon to come face to face with a powerful enemy.

Extract from 'The Twilight of French Indochina and the Forging of Modern Vietnam' by Tatsuro Yamashita

When at the start of 1945 the joint force of British, French and Italians freed Singapore and recovered most of Malaya, reopening to the Allies access to the South Chinese Sea, the Japanese forces in French Indochina on March 9th eradicated the entire local colonial administration, included the Sureté, the head of the political police force. As the Japanese would gradually relocate to safer Thailand, the Indochinese nationalists started to take control of the region. Bao Dai, the Emperor of Annam (Chinese term for Vietnam) tried to coalesce all the Vietnamese under his rule and build the basis of an united country, but was hindered by the growing opposition of the Communists of Nguyen Ai Quoc, who assumed the battle name of Ho Chi Min, and was able to coalesce a strong enough independence Front (the Viet Minh), preparing a general insurrection for the late Summer of the same year.

But around May, the French would land in Indo-China, retaking Saigon. Ho Chi Min, despite knowing the Viet Minh wasn’t fully ready, decided to act before the French would retake all of Vietnam. While the Viet Minh managed to take Hanoi and the Tonkin region, they were too fatigued to proceed towards Annam proper, where Bao Dai, despite his own difficulties, had still some support. After pondering whether to abdicate in exchange for the Viet Minh to retain a relevant role in an unified Vietnamese government, he decided to turn to the French and negotiate with them. Now, as in Paris they realized ahead of time that restoring the old colonial system would have been impossible, but also being determined to still be the arbiters of the region, in the end agreed to accept Bao Dai’s offer of surrender while allowing him to remain Emperor of Annam, thus the French to occupy more easily Central Vietnam.

With Bao Dai siding with the French, the Viet Minh offensive halted, leaving Ho Chi Min and the communist leadership on a crossroad. While the Viet Minh would publicly accuse the Emperor of having sold out Vietnam to Paris, nonetheless it barely controlled only the North. As the French would soon start to press them to lower down their arms and re-allow their jurisdiction on the Tonkin, Ho Chi Min would decide for an act of force, declaring in Hanoi the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and acting as provisional and legitimate government for all of Vietnam. Ho Chi Min believed that the USSR and the US would have supported him, the first for ideological brotherhood and the second because it appeared that Wallace was sympathetic towards anti-colonialist movements and independence groups.

But De Gaulle at Potsdam obtained from all the Allies, USA and USSR included, the guarantee that French rule or at least interest in Indochina would be fully restored and respected. Wallace, who already annoyed the British and Italians, was convinced to not annoy the French as well, while Stalin was disinterested over Indochina. Though starting to put the USSR’s foreign policy on an anti-British and anti-Italian bent, he wasn’t intentioned to anger the French in the hope to break the Western European front. While this never really happened, Stalin’s strategy wasn’t totally unsound, as until the Second Arabian War, there were significant tensions between France and Italy (over Tunisia, Syria, and in particular over Thailand) and France strongly opposed the British plans over West Germany, though never at the point of a total rupture. France had international legality to restore its own order in Indochina. Paris wouldn’t acknowledge the DRV, the DRV refused to bow, so open conflict would be inevitable. But France was unable to commence operations in the North until the March of the next year. In fact in Cambodia and Laos, the Japanese continued to fight, while British and Italians would focus over other campaigns in the area.

The Viet Minh soon discovered themselves isolated diplomatically. Not even the Chinese Nationalists would help them – Chiang had his own difficulties, and incensed against the Americans since Potsdam, would turn towards Western European support, renouncing influence in Indochina in exchange of any kind of assistance France may offer. Effectively De Gaulle would give the Kuomintang proper support and, when the fight in Indochina intertwined with the Chinese War, would send additional divisions to join the South Chinese coalition. During 1946, the French, after landing in Haiphong, being subjected to a hard bombardment and then freeing Hanoi after a strenuous city guerrilla battle, would push the Viet Minh towards the north-eastern mountains. Despite growing difficulties, Ho Chi Min would manage to keep the front united and even gain ground in Laos, where the French were more disadvantaged in terms of logistic. The occupation of most of Tonkin would cause further resentment with the Vietnamese, with looming protests and riots. Nonetheless, France would proceed to organize the region into a loose federation between Cambodia, Laos, Cochinchina, Annam and Tonkin, where Paris would have retained control on several matters, from currency to diplomatic and military affairs: but Bao Dai, who progressively aligned with the Vietnamese right-nationalist opposition, would state that only an united Vietnam could make such federation project work.

Between 1948 and 1949, as the Chinese communists seemed on the verge of victory, hundred of thousand “volunteers” crossed the border with Vietnam, assisting an ailing Viet Minh, forcing the French to lose positions in the North. De Gaulle would be forced to commit more forces in Indochina, an action that started to erode consensus around him. Bao Dai and his political allies started to capitalize over the growing French weariness and commitment failure over Indochina. Agreeing to open a new negotiation round in Paris, he would convince De Gaulle of the necessity of a united Vietnam to guarantee French interests. Obtaining from France the guarantee over Vietnamese unity, he would manage to declare at home the union between Cochinchina and Annam and Annamite administration over Tonkin, moving the capital to Saigon, and proclaiming the change of the name of the Empire of Annam to Vietnam.

As Bao Dai would start to coalesce more internal favour, the Viet Minh would start to collapse around 1951. The North Chinese support would be forced to retreat when the Coalition managed to take Yunnan, while the Viet Minh offensive in Tonkin that year failed and the French would manage to kill in a lucky shot Giap, the chief commander of the North Vietnamese army. With the death of Giap, Ho Chi Min struggled to coordinate the military effort – and after a failed attempt to siege the recently established French base of Dien Pien Bhu, he started to seek a diplomatic surrender – but he placed as condition he would surrender to Bao Dai’s nationalist supporters rather than the French.

Though Bao Dai certainly was no communist sympathizer, he knew well the population were generally Anti-French; in the Paris talks, as he managed to guarantee Vietnamese unity, he gained support and prestige at home, but still the Indochinese Federation wasn’t well seen. By taking over the negotiations with the Viet Minh, he would prove that he wasn’t a puppet of Paris and also would have started to reconcile all Vietnam under his guidance. De Gaulle and his government weren’t fully happy with this, but the French public opinion was growing tired of almost 12 years of war, whenever on their soil or aboard, and would agree on peace talks between the Viet Minh and the Empire of Vietnam. While Ho Chi Min and the Viet Minh leadership would accept surrender and dissolve the Communist Party, and disarm themselves, they would receive lenient punishments as house arrests and timed interdictions from political activities in the entire Federation; while obtaining that the Suretè wouldn’t be restored in any form and guaranteeing sufficient political freedom of protest and free press.

Thus with the Viet Minh starting to disarm, and the French completing the recovery of Indochina when the last bastions of resistance in Laos fell and the war in China turned against the Communists for good, the final decision came. On March 1st 1952 in Saigon, the protocols of the birth of the Indochinese-French Federation, formed by the Kingdoms of Laos and Cambodia, and the Empire of Vietnam were signed. These nations were all declared formally independent, but overseen by a French presidency, having authority in currency, diplomatic, military and cultural (as use of French as shared language) matters. Though French interests in the region would finally be fully restored, the Federation was still fruit of a compromise that would not satisfy fully everyone. Not the Vietnamese, nor the Cambodians, the Laotians and even the French – certainly not the socialists nor the communists. The Second Arabian War would further stress what was a weak bond between the four nations. In late 1952, Vietnam would oversee its first democratic elections, which brought into victory the nationalist right. The Emperor would name Ngo Dihn Diem, leader of the Vietnamese right first minister not long before after. Diem was likewise anti-French, and intimately hoped to get support from Italy or the US to get the nation completely out of French grip. However, both Patton and Mussolini, for different reasons, didn’t want to break the new status quo in the Far East.

Therefore, Diem and Bao Dai would have to wait for better times before attempting to slip out from Paris’s radar, focusing over the reconstruction and the recovery of Vietnam. They wouldn’t have to wait long, as the French would soon have to fight over the aftermath effects of the Second Arabian War, and decolonization in Asia was reaching its conclusion without a clear great power able to exercise an hegemonic influence. Tensions between the nations of the South East and the Far East would progressively start to boil. Not too long after the cataclysmic effects of the Second Arabian War, and the newfound rivalries that emerged from the subsequent peace, something would happen in Southern Asia that would change the geo-political picture not just in Asia, but the whole world.

Last edited:

Share: