Tube Alloys- 1938-1941

In Hitler’s Third Reich the science of fundamental physics did not exist.

There was Jewish physics, which was against the law, and German physics, the responsibility for which was vested in the

Ministerium fur Wissenschaft, Erziehung und Volksbildung (Ministry of Science, Education, and National Culture) at No. 69 Unter den Linden. Actually a Jewish woman was, until March 1938, one of the ministry’s brightest stars. Working with Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, Lise Meitner had been bombarding uranium with neutrons in the laboratories of Berlin’s

Kaiser Wilhelm Institut, and logging unbelievable results. Dr. Meitner was an exception to anti-Semetic legislation because she wasn’t a German. She was Viennese.

Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn in their laboratory in 1935.

After the annexation of Austria all Austrians were transformed into citizens of the Reich, however, and as a non-Aryan, Lise Meitner found herself locked out of her own laboratory. Her eminent colleagues went to the Fuhrer himself. Race had nothing to do with science, they argued. Physics was either true or false, and because Germany had been guided by truth, the fatherland led the world in Nobel laureates- three times as many as the Americans. Hitler angrily dismissed them as “white Jews.” A warrant for Lisa Meitner’s arrest was issued. She attempted to slip over the Dutch border disguised as a tourist, but was captured just short of freedom by the German police. Interned with political prisoners and other Jewish intellectuals in Dachau, she eventually became one of the millions of European Jews who perished in the Holocaust.

Dachau was the first concentration camp established by the Nazis shortly after Hitler took power in 1933. It served as the inspiration for later camps in Germany and in White America. Some 40,000 Jews, Jehovah's Witnesses, Homosexuals, intellectuals, socialists, communists, and mentally handicapped died there between 1933 and 1946 of disease, starvation, overwork, and murder.

Her colleagues were horrified and outraged, but their work continued.

In point of fact the physics community was on the threshold of science’s Elizabethan Age. Amazing discoveries were being made simultaneously in a half-dozen countries. Enrico Fermi had won a Nobel Prize for his work with neutrons. Hahn, Strassmann, Bohr, Chadwick, and the Joliot-Curies were at the forefront of investigation and driving hard. Over thirty years earlier Albert Einstein measured atomic energy in the abstract from his theory of relativity. Einstein observed that a body in motion has a great mass than a body at rest, the difference being defined by the velocity of light. Now real neutrons were splitting real nuclei, new elements were being discovered, three isotopes (types) of uranium were under investigation, and formulae had been committed to paper which, under conceivable circumstances, might translate Einstein’s theory into stupendous reality. The nuclear physicists didn’t expect the world to understand. They could hardly credit their own work. When Hahn (now in Stockholm) posted a report on his atom splitting to

Naturwissenschaften on December 24, 1938, he felt that somehow he must be wrong: “After the manuscript had been mailed, the whole thing once more seemed so improbable to me that I wished I could get the document back out of the mailbox.” But when Niels Bohr read it in Copenhagen, he struck himself on the forehead and cried, “How could we have overlooked that so long?!”

Niels Bohr, Danish physicist and later important figure in the Tube Alloys project.

They were fascinated, awestricken, frightened, and at odds with one another over what it all meant. Einstein told a reporter for the

San Francisco Times that fission could not produce an explosion. Bohr, arguing with a colleague, ticked off ten persuasive reasons whu such a device could never be built, and Hahn said of it, “That would surely be against god’s will!” But across the Atlantic there was disagreement. On the same day that Hitler forced Lithuania to surrender Memelland Leo Szilars wrote Joliot-Curie from London:

When Hahn’s paper reached this country a week ago, a few of us at once got interested in the question whether neutrons are liberated in the disintegration of uranium. Obviously, if more than one neutron were liberated, a sort of chain reaction would be possible. In certain circumstances this might then lead to the construction of bombs which would be extremely dangerous in general and particularly in the hands of certain governments.

He did not identify “certain governments.” Everyone knew; it was on all their minds: with such bombs, Hitler could rule or destroy the world.

Haunted by this specter, the giants of European physics joined together in a general migration. Leaving Fascist Italy in 1938 to receive his prize in Stockholm, Fermi canceled his return ticket in Sweden and headed for Cambridge with his Jewish wife. Young Edward Teller went to George Washington University in 1935, with Victor F. Weisskopf he would later join Einstein in Pasadena out of the way of the civil war. Bohr was packing to join Fermi in England. He suggested that Dr. O. R. Frisch- nephew to the imprisoned Meitner- remain in Copenhagen long enough to conduct a confirming experiment. On January 8, 1939 Bohr reached New York. Awaiting him was a cable from Frisch. The experiment had been affirmative- staggeringly so; the atom he split had freed 200 million volts of electricity. If uranium could be harnessed, theoretically it would be twenty million times as powerful as TNT.

Enrico Fermi, Italian physicist and one of Bohr's colleagues on the project.

Had the man on the street grasped this, he would have been as astonished by the source as by the fact. Popular notions of the scientist were of wildly impractical eccentrics- Dr. Frankensteins, giggling madly as they juggled retorts and vials and threw enormous switches. It is worth noting that the scientists were aware of their reputation and were indifferent toward it. There was about prewar nuclear physicists an informality, a casual air that would vanish in a terrible cloud seven years later. In 1939 the very word “physicist” was uncommon; many Americans couldn’t even pronounce it. Universities before the war paid men with Ph.D.s in science $1,500 a year to $1,800 a year. They accepted because they had little choice. Industry didn’t want them. In 1937, the last year for which we have reliable numbers, there were only four research opening for them in the whole country, and the mite set aside for government research was largely confined to the Department of Agriculture.

In return science was left alone. Genuinely international, scientists had no secrets from each other. Even in the Soviet Union, A.I. Brodsky could publish an article on the separation of uranium isotopes in 1939, and two of his colleagues carried out fission experiments in a shaft of the Moscow subway. (The Kremlin then ordered the work discontinued on the ground that it had no practical value.) Even when the concept of security crept in, scientific investigators didn’t worry about it. They could talk shop with the confidence that no layman could understand them. Indeed only a handful of their own colleagues knew of fission in its new context. Before leaving Denmark, Bohr had been well aware that the Wermacht might invade his little country, and he was worried about his precious hoard of heavy water- water in which the hydrogen has an atomic mass of two, invaluable for slowing down neutrons. But how many Nazis had heard of it? Very few, so he solved his problem by using a funnel to pour it into a large beer bottle and putting it in his refrigerator, where it sat through the entire war unmolested.

With the civil war disrupting most scientific research in America, it was in Britain that the first moves on the atomic chessboard were made in full view of an incurious public. The Frisch cable had been sent in the clear. The idea of coding information would have been considered absurd. Similarly, the experiment was reconfirmed by the simple expedient of reserving a Cambridge laboratory for the night of January 15, calling in Fermi as an advisor, staging the uranium test, setting up an oscilloscope to measure energy, and pushing a button. The needle registered precisely 200 million volts; duplication was that exact. To discuss interpretations, everyone moved into a lecture room across the street from the laboratory. The door wasn’t even closed, let alone locked. Anyone could have walked in from the pavement and learned the latest developments in nuclear science- provided, of course, he could understand the jargon and the graphs, charts, formulae, and chalk scribbles on the blackboard.

The Nazis knew about nuclear fission, of course, Hahn had told them in his

Naturwissenschaften article. Early in 1939 two German physicists called at No. 69 Unter den Linden and suggested the possibility of constructing a “uranium machine.” In April the Reich’s six most distinguished atomic scientists met twice in Berlin; they agreed to join in such an undertaking and keep quiet about it. Then Dr. S. Flugge, an anti-Nazi physicist, learned the details. Nobody had sworn Flugge to secrecy, and he though the world’s scientific community should know what was going on. He published an extensive report on uranium chain reaction for the July 1939 number of

Naturwissenschaften and then gave a simplified version to an interviewer from the

Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, a conservative newspaper Goebbels hadn’t yet suppressed. The inevitable copies found their way out through Zurich, slipping past censors because the material was just as incomprehensible to ordinary Nazis as it was to ordinary Brits and Americans. But the scientists in Britain didn’t know the where or the why. They though Flugge was showing them only the tip of the iceberg, and if the tip was that large then the world was in trouble. Then, that summer of 1939, came the most alarming development of all. Suddenly, without explanation, the Germans forbade the export of uranium ore from Czechoslovakia and ordered a blackout of all news about uranium. Since the known uses of uranium were confined to pottery and the painting of luminescent dials on clocks, there could be only one interpretation of the embargo. The gentlemen at No. 69 Unter den Linden must be on their way. And in truth, they were. Being Germans, they had naturally tricked out their project with lines of authority, word of which had also drifted through Zurich. It was Operation U, directed by appointed members of the

Uranium Verein (Uranium Society) and responsible to the

Heereswaffenamt (Army Weapons Department) in Berlin.

Kurt Diebner, the scientific head of Project U.

There was still no British counterpart to Operation U however, at least not until Frisch and another exiled German scientist, Rudolf Peierls, worked out a design for a fission bomb. Their design was flawed- it assumed a critical mass of only “a pound or two” of pure uranium-235- but in its general lines approximated what the final device would actually look like. They reported to Marcus Oliphant, who reported to Henry Tizard who was the Chairman of the Committee on the Scientific Survey of Air Defence of British Army. The British government established a committee to examine the feasibility of such a bomb and on May 10, 1940 the Military Application of Uranium Detonation (MAUDE) Project, better known by its codename ‘Tube Alloys’, began. While the war raged on in Europe, the scientists of the Tube Alloys Project bent themselves mightily to the task of constructing the world’s first atomic bomb.

Marcus Oliphant, the scientific head of MAUD, aka Tube Alloys.

In October of 1940 Egon Bretscher and Norman Feather theorized that a slow neutron reactor using uranium would produce two new elements as byproducts; both with an mass of 239 but one with an atomic number of 93 and one with an atomic number of 94. As uranium was number 92 on the Periodic Table, the first two transuranic elements were named for the first two transuranic planets- Neptunium for No. 93 and Plutonium for No. 94. Neptunium itself was useless for their purposes, but Plutonium, Bretscher and Feather argued, would be fissionable and easily separated from uranium. Uranium-235 on the other hand was chemically identical to uranium-238 and therefore extremely challenging to produce. Tube Alloys continued to consider alternatives such as gaseous diffusion and the use of centrifuges to obtain uranium-235 (both of which would eventually be used to construct bombs) but, the project’s approach turned firmly in the direction of Plutonium.

In November of 1940, in midst of catastrophes in France, the Allies stole a march on Project U when France’s nuclear physicists carried out a daring plan to the thwart their German counterparts. As enemy troops surrounded Paris and the College de France, Frederic Joliot-Curie led his colleagues in concealing the French cache of heavy water in the death cell of the Riom prison. Although the Nazis knew it was nearby and were looking for it, the French smuggled it out of Paris, and then out of Bordeaux aboard a British collier whilst Joliot-Curies duped his German interrogators into believing the heavy water was on another ship. It was with part of those 185 kilograms of Norwegian heavy water that the Tube Alloys team synthesized the world’s first Plutonium on February 1, 1941.

“Deus Ex” was well on its way.

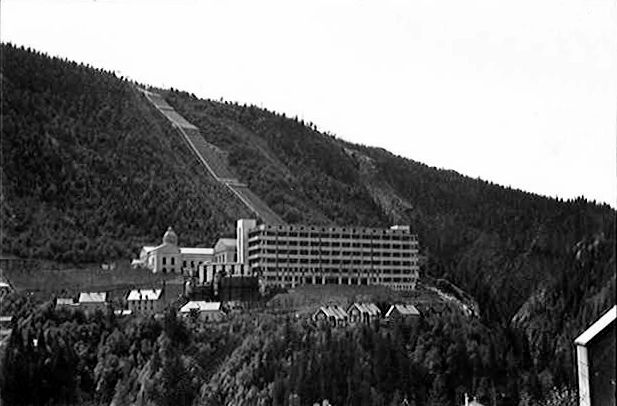

The Vermok hydroelectric plant which produced the heavy water was at the time virtually the only source of heavy water in the world.