THE TENTH DOCTOR

Victor Garber

(2008 – 2010)

For the second time in its history,

Doctor Who was settling into a new home away from home, this time on a recently-established network called the CW. Originating as a merger between CBS's United Paramount Network and Warner Bros. Entertainment's WB, the CW had inherited (alongside a litany of reality shows, game shows, professional wrestling and sitcoms) a slate of so-called "genre" series from its immediate antecedents including

Supernatural (not yet the monster hit it would soon become),

Metropolis (the so-called "sequel" series to the WB's DC Comics adaptation

Smallville) and

Willow & Faith (James Marsters and Sarah Shahi reprising the title roles from earlier appearances in

Buffy the Vampire Slayer and

Angel). [1] Recognising the popularity and long-term viability of these series and others like them, network executives devised a bloc of fantasy and science-fiction shows which would air four nights a week at 9pm, pitched to the all-important "18-34 male" demographic (although it should never be ignored, of course, that each of the aforementioned series were wildly popular with female audiences as well).

When Sci-Fi announced in trade journals during Sean Patrick Flanery's final season that it had no interest in renewing

Doctor Who for a ninth season in 2008, the CW jumped at the chance to fill out their remaining timeslot and began talks with Gallifrey Pictures almost immediately. As the eventual announcement of the new deal explained,

Doctor Who was an ideal acquisition for the network. It had sustained consistently strong ratings since 2000, came pre-loaded with a loyal international fan base and promised to bring new viewers with it, would incur lower production costs than may have been expected of such a long-running series (grandfathered into the contract negotiated with the network by the lawyers for Gallifrey Pictures was a stipulation that the company's existing arrangements with the BBC would remain unchanged subject to the Corporation's option to terminate) and, most importantly, its ability to effectively reboot with a new cast every few years was part and parcel of the show. It looked like an infinitely renewable resource, which would no doubt prove vital if

Supernatural ended as anticipated in 2010. [2] As it settled into its new home, the future of

Doctor Who seemed as bright as it was secure.

However, the transition was not without complications. For almost 10 years, Philip Segal and Verity Lambert had together been the driving force of

Doctor Who; it had been their determination that brought the show back and it was under their management that the series had ascended to heights exceeding anything it had achieved before. [3] Lambert's death and Segal's subsequent announcement of his decision to leave

Doctor Who to move on to other projects (although he intended to remain on the board of Gallifrey Pictures in a strictly advisory capacity) was met with sadness and not some concern over the future of the series. Would their replacements understand the series the way they had? More to the point, just who

were their replacements going to be?

Fortunately, plans were already in place. To begin with, actor turned prolific director Peter DeLuise was contracted by Gallifrey Pictures to serve as the programme's full-time executive producer with options to direct occasional episodes. DeLuise had first received attention for his acting roles in

21 Jump Street with Johnny Depp and subsequently in

seaQuest DSV (in which he portrayed scientist Dr Anthony Dagwood in four out of that show's five seasons [4]) before expanding into directing and production. By the time he became involved in

Doctor Who, DeLuise was best known as a prolific director, producer and occasional writer for the popular

Stargate franchise. He was recognised as a safe pair of hands capable of keeping things on an even keel behind the scenes.

However, DeLuise was not going to serve as "showrunner" for

Doctor Who. Instead, that role would be shared between two experienced British screenwriters and producers who had both been lifelong fans of the series before launching successful careers in television of their own: Russell Davies and Steven Moffat. Both writers had found their starts in the late 1980s and early 1990s working primarily in children's television; Davies with the pseudo-trilogy of BAFTA Award-winning science-fiction dramas

Dark Season,

Century Falls and

The Heat of the Sun and Moffat with the comedy-drama

Stop the Presses (which had notably featured former Seventh Doctor companion Michelle "Ace" Gomez in a leading role). From there, they had each ventured into adult drama (and in Moffat's case, some questionable but nonetheless popular sitcoms) and each wrote a handful of

Doctor Who Further Adventures novels for Virgin Books along the way. Recommended to the company by Paul Cornell and Neil Gaiman, they had each contributed several scripts to Gallifrey Pictures which had been produced during the Eighth and Ninth Doctors. When the time came for Segal to finish his association with

Doctor Who, he felt that Davies and Moffat were the ideal figures to take the series forward.

The new writers had ambitions plans for the series, envisioning an expansive three-year story arc which would require an actor with strong dramatic ability to carry off. After five years of stories with an American Doctor, the pair had also hoped to cast a British actor in the role once more. Moffat would subsequently recall that he and his co-showrunner had divergent ideas about who they should cast. "I was keen to get Peter Capaldi who I'd liked for a long time, and who'd recently been in

The Thick of It, which had done very well, but Russell wanted to get Christopher Eccleston, who we both liked. I remember we used to discuss it for hours at a time and by the time we were done, I'd be dead set on Chris while Russell had been convinced that we needed Peter!" Davies concurred, "We had a lot of different ideas: I'd been suggesting gentlemen like Michael Sheen and Jonathan Pryce and Ioan Gruffudd while Steven, as I recall, was after someone like Angus Macfadyen or Iain Glen. I liked the Welsh actors and Steven liked the Scottish ones!" [5] Peter DeLuise would later explain that the plan devised after Segal departed his full-time production role was that the series would alternate British and American actors in the title part going forward.

However, the CW would step in to put paid to this aim by requesting firmly that the Tenth Doctor be played by an American actor, at least for the purposes of the programme's debut on the network. This unexpected move took Gallifrey Pictures by surprise; for the most part, Sci-Fi had taken fairly hands off approach to the programme for most of its run on the channel (an arrangement to which the company had grown accustomed). The new paymasters were rather more eager to protect their investment and as far as the network executives were concerned, that meant retaining an American lead "for the foreseeable future". [6] In fairness to the CW, handing the reins to two largely untested (at least in the context of the American television landscape) showrunners was a big risk for the network to take on what they hoped would become one of the tentpole features of their new programming block, and despite the best efforts of DeLuise, Gallifrey Pictures acquiesced.

Even so, the new showrunners were intent that, instructions concerning the nationality of the incoming lead notwithstanding, the Tenth Doctor would be their kind of actor, and suitable for the story they wanted to tell. They began to look at American science-fiction and fantasy series, rife at the time in the wake of the success of

Lost. "Steven and I were both great admirers of Joss Whedon and J.J. Abrams," Davies would explain in 2012, "So naturally that was where we looked first. Tony Head had been brilliant playing the Eighth Doctor, but I'd say we were gravitating in an Abrams-y direction. His work really pioneered that overarching meta-plot dimension we wanted to bring to

Doctor Who." Among those considered were Bradley Cooper and Balthazar Getty from

Alias (who both showrunners thought would be too similar to Sean Patrick Flanery) and Terry O'Quinn from

Lost ("He'd have been a brilliant Doctor," said DeLuise, "But I don't think he was exactly what Russell and Steven were after for what they had planned."). [7]

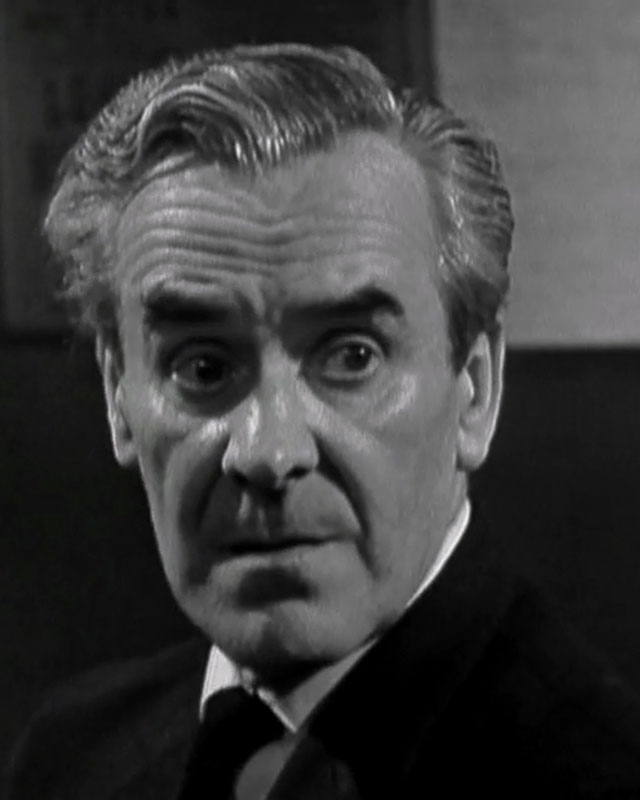

In the end, Davies and Moffat were unanimous on their choice for the Tenth Doctor:

Alias star Victor Garber, who had previously won a Primetime Emmy Award for his portrayal of Jack Bristow, FBI agent and father of Jennifer Garner's series lead Sydney Bristow. For his own part, Garber, much like his immediate predecessor, was unfamiliar with

Doctor Who and was at first reluctant to sign on to what he suspected would be another long-term contract with another science-fiction series only a years after the conclusion of his last one, instead expressing a desire to return to Broadway. Nonetheless, he was won over by the enthusiasm of the new showrunners and impressed enough by the scope of the ideas pitched to him to put these plans on hold, particularly after they made clear that their arc was planned to last for three seasons, after which Garber would have the option to either renew or terminate his contract as he wished. With that, Victor Garber was on board. [8]

With everything in place, Davies and Moffat were ready to execute their vision. Their plan involved changing the status quo for the Doctor completely with an ambitious story arc in three distinct acts (one corresponding to a season of the programme) which Davies had originally devised called "The Time War"; a conflict between the Time Lords and the Daleks with the Doctor caught in the middle. (In fact, when the first three seasons of the CW run of

Doctor Who would subsequently receive the subtitle when released as a DVD collection.) The plot was larger and more complex than anything

Doctor Who had tried at just about any point in its history, beginning with the confused, angry, newly-regenerated Tenth Doctor losing control of his TARDIS and forced to "run the gauntlet" against a series of enemies and challenges by the Great Intelligence, all the while trying to puzzle out the erstwhile villain's plan. Along the way, he gathers almost against his own will an unusual team of new companions including secretive self-proclaimed "Time Agent" Captain Jack Harkness (John Barrowman), the beautiful but deadly criminal mastermind Lady Christina de Souza (Michelle Ryan) and most surprisingly of all, his old foe the villainous Time Lady the Rani (

E.R. star Alex Kingston), who he successfully captured and manged to confine to his TARDIS.

Altogether, this group of companions were more like a shanghaied crew than the friends the Doctor had traditionally invited to join him, but they suited the darker, more intense personality which Garber and the showrunners gave the Tenth Doctor. No sooner had the pieces been arrayed on the board than would, the Great Intelligence, as infuriatingly reticent as ever, reappeared to inform the Doctor that he had passed his first test. After that, the Doctor was unexpectedly recalled to his home planet for the first time in several real-world years by his old friend and former traveling companion Borusa, who has regenerated (with British actor Alice Krige stepping into the role) and ascended to the Lord Presidency of Gallifrey. The Doctor is informed that for much of his lives, he had been fighting a war they did not even know had existed, the Time War between the Time Lords and the Daleks. [9] She now wishes him to witness the shocking resurrection of the ancient leader of the Time Lords – Rassilon, played to sinister perfection by British actor Don Warrington – by a shadowy sect known as the Cult of Gallifrey using a relic of the classic series; the Gauntlet of Time.

While the Doctor is deeply suspicious, Rassilon promptly assumes control of Gallifreyan society using his psychic powers, the Gauntlet of Time and his cadre of fanatical followers and declares that the Time Lords should no longer act as mere curators of time, but as its conquerors. Once the Daleks had been defeated, the Time Lords would be the undisputed masters of tiem and space. A sceptical Borusa is soon removed from her presidency by Rassilon's agents who install their master in her place; Borusa instructs the Doctor and his team to investigate the Cult of Gallifrey before being placed in suspended animation on Rassilon's orders. Thus ended Garber's first season as the Tenth Doctor, which achieved very high ratings and enjoyed great acclaim among both television critics and most fans (even though the reimagining of several aspects of the character's history remained very controversial, as would be subsequent revisions in the coming seasons).

In the Tenth Doctor's second season, the Time War began in earnest, with many episodes set against the backdrop of the increasingly destructive conflict between the Time Lords and Daleks with the crew of the TARDIS in the middle, struggling to prevent wanton destruction on both sides while trying (occasionally aided by the Great Intelligence, who, in a major twist in the third season, was later revealed to be trapped physically in a possible future where the Time Lords won the war and was shepherding the Doctor toward a Dalek victory to ensure his own freedom) to unravel the mystery of the Cult of Gallifrey. An additional complication emerged when Rassilon, realising that the Doctor had turned against him, used the Gauntlet of Time to resurrect his arch-enemy, the Master, as an agent charged with stopping him, [10] leading to another memorable confrontation in the second season finale. Other subplots pursued in the last season included the exploration of a two-year gap in Captain Jack's memory, the contents of which would prove crucial to the endgame of the Time War storyline, Lady Christina's pursuit by Jack's fellow Time Agents and an unlikely budding romance between the Doctor and the Rani, which ended in tragedy when she was murdered by the Master with a virus that disrupted her ability to regenerate.

The Tenth Doctor's third and final season – which also fell in the tenth anniversary year of the transatlantic reboot of

Doctor Who – focused almost exclusively on the Time War plot, with every episode connected in some fashion to the season's arc. It would complete the trilogy with a veritable extravaganza of cameos from recurring characters and classic actors, call backs to events from classic stories, the return of Ron Perlman as Davros and even a surprise guest appearance from Anthony Stewart Head as the Eighth Doctor. [11] A controversial eleventh hour dimension was added to the Time War story arc in the form of the Silence, a mysterious alien race whose true nature and motivations could never fully explained in the time available; capable of erasing the memories of anyone who saw them, they had previously encountered Jack Harkness in the 51st century, where he learned how to overcome them and purposefully locked away the missing two years of his

own memory of them to prevent them from erasing it. Ostensibly agents of the Great Intelligence, they were revealed to be the power behind the Cult of Gallifrey and the ones ultimately responsible for the resurrection of Rassilon. [12] In the two-part season finale, "The Medusa Cascade", the war reached its final reckoning when the Daleks stole a number of planets to fashion a "reality bomb" capable of penetrating the otherwise impregnable defences of Gallifrey. In fact it was a trick designed to lure the Time Lords into a trap; a final clash in which he expected they would simply be crushed by sheer weight of Dalek numbers.

At the height of the ensuing battle, the Master characteristically double-crossed everyone else (for a change; the character even quipped that it usually

him who was betrayed at the moment of his own victories) and revealed himself to be in league with the Silence, successfully taking the Gauntlet of Time from Rassilon and "retconning" Davros out of history, creating a massive paradox that seemingly destroyed all the Daleks unprotected by the energies of the Medusa Cascade. Declaring the war won for the Time Lords and himself as Master of reality, the villain was robbed of his victory when the Doctor trapped all of the participants in the Cascade and placed a "time lock" on the events of the Time War using a paradox machine designed by the Rani. For narrative purposes, the effects of the war on the universe were effectively undone, but at the cost of trapping the Time Lords and the remaining Daleks in a separate dimension from which they could never escape. The Doctor had effectively rendered himself the last of the Time Lords.

Thus ended the story that Davies and Moffat had sought to tell. It was widely celebrated in stereotypical "fan" or "nerd" circles for its "epic" scope and ostensibly mature standard of storytelling, seeing its creators hailed as heroes of the franchise. However, in later years, fans began to adopt a more nuanced and equivocal view of the sprawling Time War saga. For all its technical achievement and high ambition, the story arc never quite felt

entirely cohesive, no doubt as Davies and Moffat began to pull in different directions as it progressed.

Part of this was no doubt a result of Davies's voluntary reduction of his role in the final Tenth Doctor season to care for his partner, who had recently been diagnosed with cancer, leaving Moffat to resolve the story. While Steven Moffat remains very highly regarded as a talented writer of memorable moments, scenes and individual episodes and generally more ambitious than Davies regarding the possibilities of time travel, his large-scale plotting was generally perceived as a shortcoming which hampered the series at a crucial moment. At the same time, it would be unfair to suggest that Davies, notorious for his reliance on convenient "reset button" endings, would necessarily have enjoyed any greater success had had handled the same stories largely on his own. In any event, the Time War was ultimately characterised as a brave experiment, often successful, but with a reach that frequently exceeded its grasp.

Nonetheless, one aspect of the story arc which was unquestionably successful was Garber's portrayal of the Tenth Doctor. While the unapologetically dark twist he gave to the character was sometimes a source of controversy, few could dispute that he had used his considerable personal gravitas and charisma to brilliant effect and turned out one of the most effective performances in the programme's history. At the end of the day, though, Garber decided to exit on a high note and made clear that he would not be exercising his option to extend his contract for another season.

He would be a tough act to follow, but it was time for a change once again.

----

[1] This line-up would be supplemented (after the endings of Willow & Faith in 2010 and Metropolis in 2012) by newer additions such as The Vampire Diaries and, from 2012 onwards, a raft of very popular series set in an interconnected shared universe based on adaptations of Action Comics properties. Popularly referred to as the "Batverse", the first instalment in this franchise was Batman: The Caped Crusader, which starred Teddy Sears as Bruce Wayne and Robbie Amell as Dick Grayson.

[2] It did not. Even today, 13 years later, there is no end in sight for Supernatural.

[3] As an indicator of their impact, Lambert was posthumously awarded a special BAFTA Award in recognition of lifetime achievement in 2008, while Segal – once something of a hate figure among British Doctor Who fans who held him responsible for "Americanising" the series – would famously take the stage to a standing ovation for a panel at the London Doctor Who Festival at Wembley Arena in 2009.

[4] DeLuise's co-stars on seaQuest had included former Doctor Who companion Stephanie Beacham in the lead role of Captain Natasha Bridger and former Jaws actor Roy Scheider, for whom DeLuise's character had been a replacement in the main cast but remained associated with the show in a recurring capacity. Another future star featured in seaQuest was Jonathan Brandis, a former child actor who would subsequently find fame portraying Anakin Skywalker in George Lucas's Star Wars prequel trilogy.

[5] In a 2012 interview with DWM, he made a surprising revelation that he and Moffat had come close to agreeing on Scottish actor David Macdonald, another lifelong Doctor Who "super fan". Macdonald declined reluctantly, citing a desire not to relocate his young family across the Atlantic, but would later attain fame in America when he was cast in the lead role of Rick Grimes in AMC's adaptation of Robert Kirkman's zombie apocalypse comic The Walking Dead. Fans to this day speculate on what might have been.

[6] "They had a couple of proposals," confirmed Peter DeLuise, "I remember getting all these notes from some guy up the chain saying, 'Use Alexis Denisof or David Anders – everybody thinks they're English anyway.' And I've got to confess I was pretty blown away to learn they weren't!"

[7] Aside from alumnus of Abrams TV series, actors discussed by the producers also identified David Strathairn, Edward James Olmos, Avery Brooks and Robert Patrick as possible Tenth Doctors.

[8] Ironically, after all the pressure to cast an American actor as the Tenth Doctor, nobody at the CW seemed to have realised that Garber was Canadian.

[9] Davies commented that the events of Terry Nation's 1975 serial "The Mystery of the Daleks", in which Christopher Neame's Fourth Doctor is sent by the Time Lords to try and destroy the Daleks before they can be created, was in fact the "opening salvo" of the conflict.

[10] Played this time by British actor Jason Isaacs.

[11] Sean Patrick Flanery was invited to return, but felt it was too soon after his own departure to reprise the Ninth Doctor role.

[12] Retrospective accounts suggested that the "Cult of Gallifrey" and "the Silence" were respectively Davies and Moffat ideas which both showrunners were eager to include but unable to fully do justice in the space they had allowed themselves, resulting in their "kitbashing" together into a crude and somewhat confusing amalgam. This somewhat awkward twist is frequently identified as the chief disappointment of the Time War story arc, and it is sometimes suggested that Steven Moffat (who ended up having to execute most of the final season by himself on short notice due to personal problems with which Davies had become occupied) may simply never have had a satisfactory ending in mind for his creations.