You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Dead Skunk

- Thread starter Lycaon pictus

- Start date

(This is all they know how to do. It’s not like learning to code is an option.)

Holy shit the Spanish Philipines have gone rogue! Seems this could create an interesting Spanish-Native hybrid state.... or yet another exploitative regime. Will be watching them very curiously.

A technophillic Korea is quite interesting and it will help prepare them for the coming century, though I doubt they'll get much actual modernization done without further opening the country.

2. Would it matter much if Hokkaido was hit by flooding? My understanding was that save for the southernmost parts of the peninsula, most of Hokkaido was very sparsely populated by the Japanese before colonization efforts after the Meiji Restoration.

A technophillic Korea is quite interesting and it will help prepare them for the coming century, though I doubt they'll get much actual modernization done without further opening the country.

1. Should be "much worse than that this year" maybeIt’s much worse that this year, Hokkaido and northern Honshu were hit by severe flooding that destroyed much of the harvest. Japan is a nation of 27 million—more than the British Isles—and has to rely on itself for food. It’s never more than one bad harvest away from famine.[3]

2. Would it matter much if Hokkaido was hit by flooding? My understanding was that save for the southernmost parts of the peninsula, most of Hokkaido was very sparsely populated by the Japanese before colonization efforts after the Meiji Restoration.

Was this supposed to be "poor are getting poorer"? Otherwise this part of the sentence does not make sense to me.The rich are getting richer, the poor are getting children

I think the original phrasing is correct - "the capital burned down again, but that's fine, it's much worse that Hokkaido and parts of Honshu flooded" - or to rephrase, "it's much worse that Hokkaido and parts of Honshu flooded than it was that Edo caught fire"1. Should be "much worse than that this year" maybe

The statement is that population growth is higher in the lower classes than the upper, which a) creates potential famine issues b) makes inequality worse by reducing the relative size of the ruling class, since there are only so many open positions in the bureaucracy and few other opportunities for social mobility c) makes inequality worse by increasing the resource demands on the lower classes.Was this supposed to be "poor are getting poorer"? Otherwise this part of the sentence does not make sense to me.

SuperZtar64

Banned

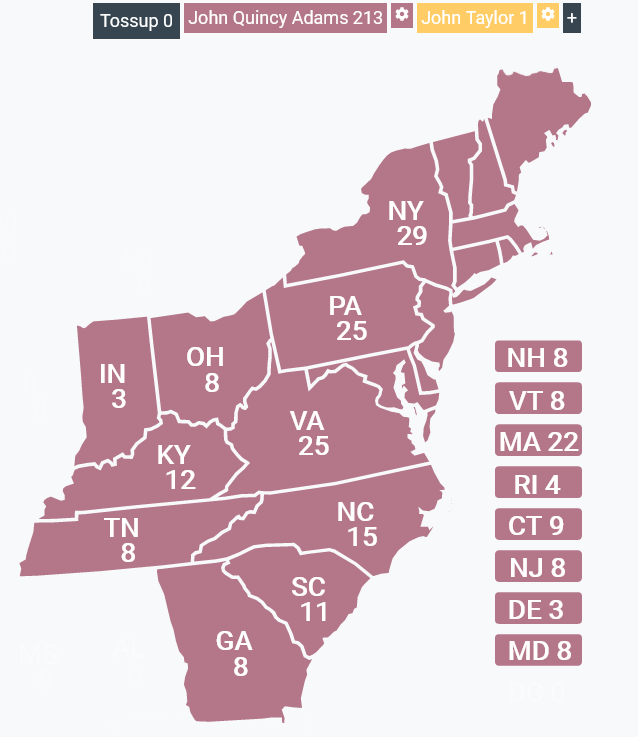

Electoral map for 1816

*One faithless elector in Delaware cast a vote for John Taylor.

*One faithless elector in Delaware cast a vote for John Taylor.

Lycaon pictus

Donor

Awesome work, SuperZtar54.

(And please tell me SOMEBODY got the "Ain't We Got Fun"-via-the-Great-Gatsby reference.)

(And please tell me SOMEBODY got the "Ain't We Got Fun"-via-the-Great-Gatsby reference.)

Winter Games (1)

Lycaon pictus

Donor

The Class of 1824: Ten Years Later

John Coffee Hancock turned 10 on January 11, and is the top student in his year at Norristown Academy. His father’s a schoolteacher, so his family didn’t do as well as most during the good time, but haven’t been hurt so much by the bad times either.

“Keep your men in good order and your supply lines open, and there is no disaster that cannot be put right.” — Gen. Hancock

Denton Johnson Brooks turned 10 on February 15. He’s a decent student, but can’t stop getting in fights.

“For more than two years, every time I sat down to wine and pizza with my friends, I heard them say, ‘It’s dreadful, somebody ought to do something, somebody should do something.’ Well, now somebody has.” — Denton Brooks

Elizabeth Miller turned 10 on March 27. She has two older brothers, a younger half-sister and a younger half-brother, and her once-thriving family is, like a lot of families in Charleston these days, struggling with debt.

“I have seen two wars, and between them the Troubles. When actuaries tally up the number of human lives lost to violence, they find all the years of the Troubles scarcely add up to one battle, but mark me—the Troubles were the worst. The wars were titanic monsters whose roar could be heard long in advance of their approach. The Troubles were a small but deadly serpent that might strike from anywhere.” — Elizabeth Miller

Francisco Agustín de Borbón y Iturbide turned 10 on April 9. He’s an okay student, but (like both his paternal grandfathers) an excellent horseman. He treats his younger brothers and sisters well. The plan is that he will learn to be a soldier, be promoted to general and—when his father dies—become the strong right hand of whichever younger brother of the Miraculous Princess is sent to New Spain to become the new Prince-Viceroy.

“We will hold the Misión de Álamo against Hell itself if necessary.” — Francisco Agustín de Borbón y Iturbide

Charles Brady turned 10 on May 1. With the economy the way it is, his father’s had to go into the timber industry in the mountains around Lake George—the railroads always need more wood—and to bring Charlie’s older brother and himself along. Charlie likes the woods. He’s growing up on folktales from Ireland and elsewhere, and wants to hear whatever tales come from the Adirondacks. But there’s hardly anybody left in the Adirondacks who isn’t cutting trees, so Charlie’s having to make them up himself.

“Seven men stood on the height overlooking the Klondike. They gazed upon a vista of hills like a crowd of balding men, naked crowns of rock and heatherish tundra rising above sparse forests of spruce and fir. They heard the cries of ravens, but saw no other living creature than themselves in any direction…” — The beginning of The Wendigo by Charles Brady

Edward Allingham turned 10 on June 20. His mother died in childbirth this year, and the baby died a few days later. Edward and two younger siblings, Charlotte and John, remain.

Edward is a devout Anglican from a long line of such, and his elders are still talking about the Tithe War and how the government will rue the day it let those “grubby Papists” win. He himself can’t help wondering why the Church of Ireland has to keep hitting up the supposedly poor, second-class Catholics for money.

“Do as you will with me. I will not oppose these people in arms again until their concerns have been addressed.” — Gen. Allingham

Solomon Parsons Morton turned 10 on July 24. His family moved to Springfield, Vermont a couple of years ago. He’s an okay student, but a leader among his peers.

“Can I continue pressing the attack? Only until I die, sir. I offer no guarantees for my performance afterward.” — Col. Morton

Josephus Starke turned 10 September 21. In the hills of northern Alabama, it’s becoming harder and more dangerous for the sheriffs to enforce eviction notices. Too bad for the Starke family that they’re at the opposite end of the state. Plantation owners can organize to resist evictions, but they don’t try to protect little farms like the Starke place— they’re thinking that when times get better, one of them can buy the land from the bank cheap. Which is how the Starkes wound up in North Carolina working for the railroad from Salem to Charlotte. Josephus can’t wait until he’s old enough to help his family earn some money. That’s the height of his ambition… at the moment.

“Kentucky is mine. Get your own damn state.” — Josephus Starke

Dheerandra Tagore turned 10 October 13. He already reads and writes six languages. The Company is particularly strong where he is, and his parents are hoping he can get a job serving it. They always need more translators.

“Queen Charlotte freed the slaves, but she did not free us. Very well. We’ll do it ourselves.” — Dheerandra Tagore

Karl Peter Frederick, son of the Grand Duke of Oldenburg, turned 10 on November 19. He’s already sharp enough to follow the debates in the newspapers. Two years ago his father granted his people what was more or less a copy of the Hanoverian constitution, and there are no customs barriers between Hanover and Oldenburg. This has actually diminished the calls for unification with Hanover—it’s easier to leave the status quo in place, and that amounts to practically the same thing. Plus, Oldenburg is a Grand Duchy. It wouldn’t be grand anymore if Grand Duke August became the vassal of King Wilhelm.

The railroad between Hannover and Oldenburg (okay, really the railroad between Hannover and Bremerhaven[1], but it connects Oldenburg) was completed this year, which means Karl can visit Hannover often, and does. Prince Victor Alexander is like the cool older brother he never had.

“Berlin or Hannover—one of these two must fall. I do not know which one will win, but I know where I will fight.” — Grand Duke Karl

Nathanael Greene Whitman turned 10 on December 22. He’s still in school. He’s a somewhat better-than-average student, but his artistic skills are well in advance of his years.

“When I heard the learn’d chemist discourse on the wonders of the argentograph[2], and show the proofs that this mechanical marvel could create more realistic images of the natural world than those of any human hand, I became sick and sad. Then the thought came into my mind that human imagination still must govern the composition of every image, and that this mere machine, like the pen and brush, might itself be made an instrument for the expression of art.” — Nate Whitman

February 11, 1835

U.S. Capitol

Senate Majority Leader—and President emeritus—Henry Clay had anticipated that this was going to be a difficult term. He hadn’t realized how difficult. The Democratic-Republican majority in the Senate still existed, but had been reduced. His felllow Kentucky senator, Richard Mentor Johnson, had been replaced by Joseph Desha, a Quid and a man he personally detested. That one-eyed grump Governor Harrison of Ohio was still sending him angry missives about the Supreme Court decision last year.

And now this—the publication of an open letter, which was the reason he and the two most powerful Dead Roses in the House were meeting in Webster’s office. “‘Whereas the peculiar institution of the South is the mainstay of its agriculture and the backbone of the industry that supplies so much of our exports…’” He didn’t trouble to read aloud the rest of the justifications.

“‘Be it known that if the Democratic-Republican delegation to the United States Congress were to put forward any further proposals having in their effect the diminution of this institution in the states where it is currently lawful, we the signatories would be compelled to resign our membership in said party…’” (The signatories, not the undersigned. Just to make everyone’s day complete, the letter was a round robin. The signatures were around the edges in an irregular pattern that concealed which of them might have been first to sign it, although Clay would have bet half his railroad shares on Rep. Taney of Maryland.)

“Twenty-five,” said Speaker of the House Webster. Everyone in the office could do the math. If only fourteen of the signatories made good on this threat, the Quids would have a majority and Webster would have to hand over his new position to Calhoun.

“The Liberationist delegation has informed me,” added Majority Whip John Quincy Adams, “that if we don’t publicly defy this missive at once, they will leave our coalition.”

Clay smiled grimly. “Both of them?”

“Strictly speaking, there are three. Sumner from Massachusetts, Stevens from Pennsylvania, and… someone from Kyantine who I haven’t met.[3]”

“From Kyantine? Not a Negro, surely?” Even Clay would have found it embarrassing if a Congressional representative were kidnapped by slavers, which was a risk in D.C.

“A white man. I’ve heard a little about him, but I can’t recall his name. I know it’s something quite forgettable—John Smith, John Jones, John White… no, not John White, but something of that sort. All I remember about him is that his family settled at a place called Oak Hill[4] and they have a tannery there. I suspect he owes his election to the fact that they thought it best to find a white man for the position and had very few of any merit to choose from. In any event, he does not vote, so we needn’t worry about him. For all practical purposes the Liberationists have only two.”

Clay turned to Webster. “What say the Populists?” Half the reason Webster had been chosen as Speaker of the House was that he seemed to get along better with the Populists.

“They leave the matter in our hands.” That was only a little better. Depending on the Populists meant making choices that might make some voters happy in the short term, but—Clay greatly feared—would harm the nation in the long term.

“You both know these men better than I do,” said Clay. “How likely are they to make good on this threat? This fellow from New York, for instance…”

Adams snorted. “Rep. Fillmore is a weathervane with feet. He represents whatever he believes the consensus to be.”

“A weathervane? No sense getting angry at him, then. The problem is which way the wind is blowing.” Clay pointed to another signature. “And this one’s from New Hampshire. Is he serious? What’s his name—Franklin… Pence?”

“Pierce,” said Webster. “Newly elected. I’ve met him. Young fellow—no more than thirty, and he looks like a schoolboy.”

“An ambitious young man.”

Webster nodded.

“And yet willing to risk his career over this. And what worries me are the other names. These are all our remaining representatives in Missouri, Tennessee, Kentucky, and most of our Maryland and Virginia delegation.” Clay shook his head. “If they go over to the Quids, who will be the national party then, and who the regional party?”

“I agree,” said Webster. “We can’t risk it. And consider—did any of us have plans to take action against slavery within the states where it holds sway?”

“Unfortunately, no,” said Adams.

“Then it costs us nothing but a touch of pride to heed this warning. And after all, they aren’t asking us to expand slavery. ‘In the states where it is currently lawful’—those are their exact words.” He pointed at the sentence on the page. “Michigan is already a free state. And when other territories apply for statehood, what will these signatories do? Deny them representation? Force them to accept slavery in order to join? I doubt it. We have suffered a great defeat, this is one of the consequences, and we must needs endure it. But in this matter, Time remains our friend and ally.”

“When you say ‘our,’” said Clay, “are you speaking of the Dead Rose caucus, or the anti-slavery caucus?”

“I am speaking,” said Webster, not missing a beat, “of those whose loyalty to the party is greater than their loyalty to slavery.”

Clay nodded, keeping his expression neutral. Bringing up future states in this context had brought to mind something he tried not to think about too much. Wisconsing, Ioway, Mennisota, Kaw-Osage… none of those would be a problem, come the day. If the Tertium Quids tried to bar them from the union in the name of slavery, the very next election would send them right back to minor-party status where they belonged, and the voters in the new states would be of a mind to hold them there forever.

But what of Kyantine? Could there be a state in this Union where whites were not the majority? All right, there already were such states—South Carolina and, by a narrow margin, Mississippi—but could there ever be a state where the white man did not rule? Could Congress be persuaded to accept this?

It seemed unthinkable, yet the Constitution offered no bar. Clay had that text well-nigh committed to memory, and in it the words “white” and “Negro” were nowhere to be found. It spoke of “free Persons” and “other Persons” instead, and the blacks of Kyantine were indeed free persons. That America was in all its parts to be ruled exclusively by white men was a tacit agreement, and if something were to contravene that agreement…

A problem for another day, thank God.

[1] The city of Bremen is the third member of the Hannover-Oldenburg group outside the Nordzollverein that everyone always forgets about, including me.

[2] IOTL daguerrotype

[3] Each organized territory sends a nonvoting representative to the House.

[4] IOTL Tulsa. It should be noted that the Brown family lives and works on the other side of the river from Oak Hill proper, which is at the southern end of Kaw-Osage territory.

Last edited:

👀👀👀A white man. I’ve heard a little about him, but I can’t recall his name. I know it’s something quite forgettable—John Smith, John Jones, John White… no, not John White, but something of that sort.

Winter Games (2)

Lycaon pictus

Donor

You just inspired me to write an extra post.I need to know more about the offhand reference to pizza

May the Lord above forgive me for what I must do this night

I have shared their wine and pizza—now we fight!

(Susan Grace, Act III, scene 2)

I have shared their wine and pizza—now we fight!

(Susan Grace, Act III, scene 2)

And may the Lord above forgive me for quoting grand opera—and Susan Grace at that—in what is supposed to be an informal, generally positive guide to the American South. But this is the part where we talk about pizza, so I just had to throw that in.

If you ask where pizza was invented, anyone from Fort Gaines[1] will tell you, “It was invented here, and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise!” According to actual historians, people started putting toppings on flatbread and then baking it almost as soon as they invented the oven. Tomatoes entered the picture in the 16th century, and around 1800 or so, dockworkers in the port of Naples were eating something vaguely similar to modern pizza. It was cheap and easy to make, and they could eat it quickly and get back to work.

Then came the Other Peninsular War, which was a pizza of death with all the toppings—famine, guerrilla warfare, murder of civilians, and in Naples in particular, Morisset, a tyrant like something out of a K-dread[2]. No surprise that a lot of Italians were heading for someplace less blood-soaked and horrible.

Which brings us back to America. The South didn’t normally draw a lot of immigrants—if they wanted cheap labor, they had slaves for that—but the creation of the Southern Inland Navigation Company created a sudden demand that they couldn’t completely fill. So from October through May of every year, there were Italian-Americans digging the ditches that would become the T&T and Grand Southern.

Workers need to eat, and canal-building creates a lot of displaced earth—especially the clay subsoil that’s great for building earth ovens. Walking along the banks of a canal, you’ll still see these ovens today. From a distance they look like lumps in the ground covered in moss and surrounded by weeds, but if you find the entrance and look really close, you can just about get bitten in the face by a possum which is trying to raise its babies in this little man-made lair.

As in Naples, pizzas were something cheap to make and quick to eat, but the pizzas they ate while working along the canals were even less recognizable than the early Neapolitan pizzas. All they had to work with was flour, cheese and salt pork, and maybe a little lard. Tomatoes (fresh or preserved) were almost never available. Worse, the flour was cornmeal, so the bread shattered into what one observer called “edible potsherds” as soon as you picked it up. Authentically made canal-crew pizzas are almost impossible to find these days, but I’ve tried a few. Trust me, you’re not missing anything.

But again, this was October through May. It was SINC’s way to use slaves for the hotter months of the year. So what did the Italians do during the summer? Well, some of them had used their earnings as collateral to get loans from the Bank and purchase little bits of land for subsistence farming. Others went up into the mountains and started vineyards—little ones, not the great vineyards of the Frescobaldis and Antinoris. And some of them sold food.

So by the time the canal bubble burst, there were pizza bakeries in every town and city along the canals, not to mention the wine-market towns like Salgemma[3] and Yadkinville. At this point, they were still mostly using corn, with just enough wheat flour to hold the bread together into slices. But as they made more money, they could afford more wheat flour, which improved the quality of the bread, which made them even more popular. They could also afford to mix vegetable oils in with the lard, although it would still be a big deal when (generations later) cheap olive oil came to the American market.

Which isn’t to say that they were immediately popular. At first, they were thought of as places where poor white people ate—or, in some neighborhoods, freedmen—and some of them were suspected of being stops on the Hidden Trail. This was sometimes true. The one confirmed example is Baldy’s Best Bakery in Peacross[4], owned by the Baldy (formerly Garibaldi) family, where Joseph Marius “Wild Joe” Baldy would sometimes hide out after one escapade or another. (Don’t bother looking for it. It was destroyed during the Troubles, and the site is now a fishing supplies store.)

Things changed in 1833. The Hiemal Period was hell on most businesses, but the bakeries survived. Their ingredients were cheap and deflation made them cheaper, and while some people could no longer afford to eat there, others who wouldn’t have been caught dead there before found that the local pizza bakery was the only place they afford to eat out. And like so many before them, they found out that pizza is delicious.

The Savannah Fire had a more dramatic effect. You can’t burn down a brick oven, so the bakeries were among the first places to recover and reopen after the fire, and became places for the suffering community to meet and take notes on how they were coping.

Upper-class Southerners, of course, were great correspondents, and word spread everywhere. People who’d never seen a pizza bakery were getting instructions on how to make their own pizza—or, more likely, how to get the slaves to do it—when friends and relations came to call. According to scholars, “wine and pizza” first appeared as a metaphor for friendship in the South around 1840.

An Informal Guide to the American South

[1] Larger than OTL’s Fort Gaines, Georgia, because the Grand Southern goes through town.

[2] Horror movie

[3] OTL Roanoke, Va.

[4] OTL Elba, Alabama.

Last edited:

oh no“For more than two years, every time I sat down to wine and pizza with my friends, I heard them say, ‘It’s dreadful, somebody ought to do something, somebody should do something.’ Well, now somebody has.”

Exactly what I wanted! Fantastic update, very happy I inspired you to dig in on the subject.

My only question: coal. It’s a marginal but real improvement vs wood fired ovens, and I suspect the lighter regulation plus stronger historical attachment to coal mining in the South might result in a ton of modern day pizzerias still using coal. As opposed to today in North America where there’s one oven in Montreal, IIRC a handful in NYC, and none else offhand though there’s probably a couple somewhere in New England.

My only question: coal. It’s a marginal but real improvement vs wood fired ovens, and I suspect the lighter regulation plus stronger historical attachment to coal mining in the South might result in a ton of modern day pizzerias still using coal. As opposed to today in North America where there’s one oven in Montreal, IIRC a handful in NYC, and none else offhand though there’s probably a couple somewhere in New England.

Winter Games (3)

Lycaon pictus

Donor

March 2, 1835

10 Downing Street

“Thank you all for coming,” said Grey. “We have a decision to make.”

He was sitting at one end of the table in the Cabinet Room. At his right hand was Viscount Melbourne, Chancellor of the Exchequer. On his left was Home Secretary Henry Brougham (now Baron Brougham and Vaux[1]), using all his mental discipline to convey an air of calm in front of the rest of the Cabinet even as he wondered if he’d have an office or a career when this meeting was over.

Nothing he’d done in the past six years could be considered a failure, but in the last election the Whigs had gone down from 445 seats to 369. They still had a majority, but the writing was on the wall. If the material condition of the nation did not sharply improve within the next few years, they would lose the next election. In the meantime, going forward without major changes in the Cabinet would be the height of arrogance—and Brougham had enough self-awareness to know that his standards of arrogance were quite high to begin with.

“Under the circumstances, I can no longer serve as Prime Minister. Myself and William”—he gestured to indicate Lord Melbourne—“will step down and return to the back benches. I propose we replace him with Earl Spencer.”

“Spencer would be an excellent choice, if we can persuade him to take the position,” said Melbourne. The third Earl Spencer had been raised to the Peerage and inherited his father’s estates two years ago.[2] Since then, he’d spent most of his time on his estates with his two children.[3] “If he refuses, I’d suggest either Charles Poulett Thomson, or recalling young Canning from Paris[4].”

Brougham was hoping Spencer could be persuaded. Given the nature of the troubles that had struck the realm, it was natural that whoever was holding the office of Exchequer at the time would have to step aside whether it was his fault or not. Brougham wasn’t sure anyone could fix what was wrong, but Spencer was trusted, and rightly. Even if he failed, the public might not hold the Government responsible for his failures.

“There are other retirements, mostly due to age,” said Grey, “but first we should decide whose name to offer to Her Majesty as Prime Minister.”

As it happened, seated at the other end of the room were Lord Palmerston, Foreign Secretary, Lord John Russell, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, and Lord Durham, Lord Privy Seal—all in a row, framed by the two sets of pillars behind them. Grey’s gaze swung from side to side like the needle of a metronome at its slowest setting, not favoring one of them over another, not looking to anyone else in the room.

Palmerston in his fifties, all pragmatism and cynicism. Durham in his forties but looking younger and full of idealism. And right in between them physically and in outlook, Russell, in his forties and looking it.

The three men glanced at each other. None of them spoke. False modesty? thought Brougham. Or something more?

Seconds ticked by on the clock, one after the other. Everyone had their eyes pointed at those three men. Palmerston. Russell. Durham. Palmerston. Russell. Durham. In the silence, each tick seemed to be louder than the last.

Brougham’s mind raced. None of them wants the office. Not this year. They all think we’re going to be trounced in ’38, or sooner if we lose a vote of no confidence. They think the Prime Ministership has become a poisoned chalice, and they daren’t take a sip. They think being in charge for the next three years will ruin their prospects. And they’re probably right.

But if Grey picks one of them, he can’t very well say no on the grounds that it would jeopardize his future career.

But Grey doesn’t want to do that to one of them.

But we need somebody to be Prime Minister.

And this year Brougham would turn 57—though he still felt quite young[5], he could do the arithmetic. This opportunity might never come again. They were hardly going to give you the job when everything was going very well. They fear you too much for that. Here was another moment like the one fifteen years ago, when the time had come to face down Lord Liverpool’s government—Wellington and all—and tell them that their mischief was at an end. That hadn’t been easy, and neither was this. He drew a deep breath and lifted his head.

“I am willing.”

Everyone in the room stared at him.

“We face greater difficulties than we imagined,” Brougham continued, “but it was too much to hope for that peace and prosperity would last forever. Are we going to complain because our ship is in rough waters now? I for one am ready for the challenge.” In his younger days, he would have smiled and said I am eager for the challenge or something similar, to cement his reputation for bold ambition. Looking back, he might have cemented that reputation entirely too well. Even now, further seconds were ticking by and the little oil lamp was flickering as the others pondered the question of whether they really wanted to risk giving him this much power.

He stood and turned to the three men Grey had been looking at. “You are all serving superbly in your current offices,” he said. “You in particular, John”—he nodded to Russell—“are managing the transition away from slavery in the West Indies with great skill. And with so many crises overseas, this is not the time for an untried hand at the Foreign Secretary’s tiller. The next Prime Minister will need each of you at his side.”

No one spoke.

“And of course there’s the royal wedding to plan,”[6] Brougham added.

Another long stretch of silence. Brougham sat back down, fighting the urge to hold his breath. Had he gone too far? Shown too much of his hand? Were they all determined in their minds that it could never be him, whatever else? And if they said no to him now, what would it do to the remainder of his career?

Then Grey nodded. “Kill or cure,” he said. “And at least we know Her Majesty will approve. Whom do you propose for Home Secretary?”

“Thomas Spring Rice,” Brougham said without hesitation. At times like this, it paid to know the names of everyone who might be considered as your replacement. “He’s capable and committed to further reform. His appointment will spend a message to our Irish subjects—or our West British subjects, as he likes to call them—that we are alert to their needs, but we must have their loyalty.”

“So be it,” said Grey.

Russell spoke up. “One point. It has been many years, but I doubt the Opposition has forgotten the role you played in quashing the Pains and Penalties Act, and that one particular speech—I think you know the one I mean?”

“The ‘standing upon the brink of a precipice’ speech?”[7]

Russell nodded. “In the spirit of conciliation, perhaps… an apology? If nothing else, to set at ease the minds of our more moderate members?”

Brougham shook his head. “Credit to you, John, but no. What I said that day admits of no middle interpretation. It was either a laudable stand against folly and caprice on behalf of the British people—worthy of an apologia rather than an apology—or else it was a base act of extortion for which no apology could possibly suffice. And would I be here if this Government believed the latter?

“No. If after these fifteen years the Tories wish to re-litigate the entire Caroline affair from beginning to end, with defenses of every single action they took… well, apart from the waste of time, that is a battle I would relish.”

“I very much hope it will not come to that,” said Grey.

[1] As IOTL

[2] The second Earl Spencer died in 1834 IOTL.

[3] The third Earl Spencer died without issue IOTL.

[4] George Charles Canning (who died in 1820 IOTL), eldest son of the late George Canning, currently serving as U.K. ambassador to France.

[5] IOTL Brougham lived to be about four months shy of 90.

[6] Leopold Prince of Wales is now officially betrothed to Julia Louisa of Denmark. The wedding is scheduled for next summer.

[7] In case anyone has forgotten what they’re talking about (it’s been a while) here’s the link.

10 Downing Street

“Thank you all for coming,” said Grey. “We have a decision to make.”

He was sitting at one end of the table in the Cabinet Room. At his right hand was Viscount Melbourne, Chancellor of the Exchequer. On his left was Home Secretary Henry Brougham (now Baron Brougham and Vaux[1]), using all his mental discipline to convey an air of calm in front of the rest of the Cabinet even as he wondered if he’d have an office or a career when this meeting was over.

Nothing he’d done in the past six years could be considered a failure, but in the last election the Whigs had gone down from 445 seats to 369. They still had a majority, but the writing was on the wall. If the material condition of the nation did not sharply improve within the next few years, they would lose the next election. In the meantime, going forward without major changes in the Cabinet would be the height of arrogance—and Brougham had enough self-awareness to know that his standards of arrogance were quite high to begin with.

“Under the circumstances, I can no longer serve as Prime Minister. Myself and William”—he gestured to indicate Lord Melbourne—“will step down and return to the back benches. I propose we replace him with Earl Spencer.”

“Spencer would be an excellent choice, if we can persuade him to take the position,” said Melbourne. The third Earl Spencer had been raised to the Peerage and inherited his father’s estates two years ago.[2] Since then, he’d spent most of his time on his estates with his two children.[3] “If he refuses, I’d suggest either Charles Poulett Thomson, or recalling young Canning from Paris[4].”

Brougham was hoping Spencer could be persuaded. Given the nature of the troubles that had struck the realm, it was natural that whoever was holding the office of Exchequer at the time would have to step aside whether it was his fault or not. Brougham wasn’t sure anyone could fix what was wrong, but Spencer was trusted, and rightly. Even if he failed, the public might not hold the Government responsible for his failures.

“There are other retirements, mostly due to age,” said Grey, “but first we should decide whose name to offer to Her Majesty as Prime Minister.”

As it happened, seated at the other end of the room were Lord Palmerston, Foreign Secretary, Lord John Russell, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, and Lord Durham, Lord Privy Seal—all in a row, framed by the two sets of pillars behind them. Grey’s gaze swung from side to side like the needle of a metronome at its slowest setting, not favoring one of them over another, not looking to anyone else in the room.

Palmerston in his fifties, all pragmatism and cynicism. Durham in his forties but looking younger and full of idealism. And right in between them physically and in outlook, Russell, in his forties and looking it.

The three men glanced at each other. None of them spoke. False modesty? thought Brougham. Or something more?

Seconds ticked by on the clock, one after the other. Everyone had their eyes pointed at those three men. Palmerston. Russell. Durham. Palmerston. Russell. Durham. In the silence, each tick seemed to be louder than the last.

Brougham’s mind raced. None of them wants the office. Not this year. They all think we’re going to be trounced in ’38, or sooner if we lose a vote of no confidence. They think the Prime Ministership has become a poisoned chalice, and they daren’t take a sip. They think being in charge for the next three years will ruin their prospects. And they’re probably right.

But if Grey picks one of them, he can’t very well say no on the grounds that it would jeopardize his future career.

But Grey doesn’t want to do that to one of them.

But we need somebody to be Prime Minister.

And this year Brougham would turn 57—though he still felt quite young[5], he could do the arithmetic. This opportunity might never come again. They were hardly going to give you the job when everything was going very well. They fear you too much for that. Here was another moment like the one fifteen years ago, when the time had come to face down Lord Liverpool’s government—Wellington and all—and tell them that their mischief was at an end. That hadn’t been easy, and neither was this. He drew a deep breath and lifted his head.

“I am willing.”

Everyone in the room stared at him.

“We face greater difficulties than we imagined,” Brougham continued, “but it was too much to hope for that peace and prosperity would last forever. Are we going to complain because our ship is in rough waters now? I for one am ready for the challenge.” In his younger days, he would have smiled and said I am eager for the challenge or something similar, to cement his reputation for bold ambition. Looking back, he might have cemented that reputation entirely too well. Even now, further seconds were ticking by and the little oil lamp was flickering as the others pondered the question of whether they really wanted to risk giving him this much power.

He stood and turned to the three men Grey had been looking at. “You are all serving superbly in your current offices,” he said. “You in particular, John”—he nodded to Russell—“are managing the transition away from slavery in the West Indies with great skill. And with so many crises overseas, this is not the time for an untried hand at the Foreign Secretary’s tiller. The next Prime Minister will need each of you at his side.”

No one spoke.

“And of course there’s the royal wedding to plan,”[6] Brougham added.

Another long stretch of silence. Brougham sat back down, fighting the urge to hold his breath. Had he gone too far? Shown too much of his hand? Were they all determined in their minds that it could never be him, whatever else? And if they said no to him now, what would it do to the remainder of his career?

Then Grey nodded. “Kill or cure,” he said. “And at least we know Her Majesty will approve. Whom do you propose for Home Secretary?”

“Thomas Spring Rice,” Brougham said without hesitation. At times like this, it paid to know the names of everyone who might be considered as your replacement. “He’s capable and committed to further reform. His appointment will spend a message to our Irish subjects—or our West British subjects, as he likes to call them—that we are alert to their needs, but we must have their loyalty.”

“So be it,” said Grey.

Russell spoke up. “One point. It has been many years, but I doubt the Opposition has forgotten the role you played in quashing the Pains and Penalties Act, and that one particular speech—I think you know the one I mean?”

“The ‘standing upon the brink of a precipice’ speech?”[7]

Russell nodded. “In the spirit of conciliation, perhaps… an apology? If nothing else, to set at ease the minds of our more moderate members?”

Brougham shook his head. “Credit to you, John, but no. What I said that day admits of no middle interpretation. It was either a laudable stand against folly and caprice on behalf of the British people—worthy of an apologia rather than an apology—or else it was a base act of extortion for which no apology could possibly suffice. And would I be here if this Government believed the latter?

“No. If after these fifteen years the Tories wish to re-litigate the entire Caroline affair from beginning to end, with defenses of every single action they took… well, apart from the waste of time, that is a battle I would relish.”

“I very much hope it will not come to that,” said Grey.

[1] As IOTL

[2] The second Earl Spencer died in 1834 IOTL.

[3] The third Earl Spencer died without issue IOTL.

[4] George Charles Canning (who died in 1820 IOTL), eldest son of the late George Canning, currently serving as U.K. ambassador to France.

[5] IOTL Brougham lived to be about four months shy of 90.

[6] Leopold Prince of Wales is now officially betrothed to Julia Louisa of Denmark. The wedding is scheduled for next summer.

[7] In case anyone has forgotten what they’re talking about (it’s been a while) here’s the link.

Last edited:

Rice? Interesting pick. If the Famine comes, he'll handle it better- he could hardly handle it worse- but I'm not sure a man who thinks the island should be renamed 'West Britain' will receive any plaudits.

Share: