------------------

Part 16: New Heights, New Precipices

Although he had scored an immense victory by liberating Ctesiphon, Ardashir II didn't stay in the capital for more than a few days. He couldn't, since although the bulk of the province of Asoristan had risen up to support him, there were still isolated Palmyrene garrisons scattered all over the provinces of Khuzestan and Meshan, with the most important of them being located in the former Achaemenid capital of Susa, which had been heavily fortified by order of Wahballat the Great many years ago to prevent any Iranian attack in that direction. Thus, the King of Kings departed in early February to mop up these last few hostile pockets before Palmyra could organize a sizable counterattack. This campaign went along swimmingly, and most of the garrisons surrendered peacefully, aware that their position was hopeless, and as expected, only Susa held out for a length of time, and had to be besieged for a week before its soldiers surrendered.

With his rear secured, Arashir returned to Ctesiphon so his soldiers could rest for a while (he couldn't afford to have a mutiny again) and prepare for the inevitable attack that would come from Syria after Palmyra sorted itself out. He also needed time to properly organize the administration of the recently reconquered territories, assigning tax collectors and other such bureaucrats to multiple locations, as well as orchestrating the transfer of the court from Istakhr back to Iran's rightful capital, preparing both cities for a population transfer that involved thousands of people. He also needed to make preparations for a new, grand coronation, the ultimate sign that he and the Derafsh Kaviani flag were here to stay. Fortunately for the Shahanshah, the Palmyrene Empire's internal situation following the death of Antiochus was more dysfunctional than anticipated, which gave him plenty of time for him to consolidate his hold on Mesopotamia and do everything he wanted.

His coronation, which took place in May 8, 332 AD (a national holiday, along with January 28) was a magnificent ceremony, worthy of someone as ambitious as he was, and a statement to Iran and the world that the Sasanian dynasty was finally back in its position as one of its most powerful and opulent rulers. Some historians back then and now still criticize the massive sums of money that were diverted to it, saying that it would have been much better for the country and therefore Ardashir himself if they were spent on equipping and improving the army, rather than on fancy dresses and exquisite plates and similar pieces of artwork that still exist to this day. Meanwhile, others say that all the pomp and circumstance were necessary in order to show that the age of Palmyene domination of the Middle East was over.

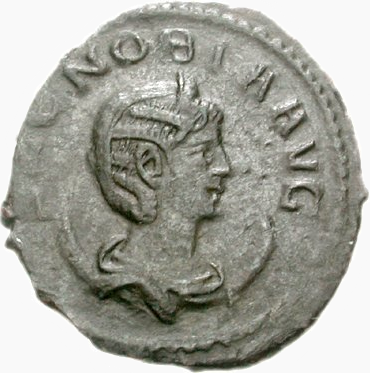

A bust of Ardashir II made shortly after his coronation (1).

Whether the coronation was necessary or not, the euphoria it generated couldn't last forever. By late October, Zenobius, who had taken the throne of Palmyra after his brother's murder, sent an army of 60.000 soldiers to capture Ctesiphon and drive the Iranians back to the east of the Zagros. However, due to his inexperience and fear of sharing his predecessor's fate, he decided to stay in Syria, handing the command of this powerful force to an influential and ambitious general named Zabdas, a descendant of the general of the same name that served king Odainat and queen Zenobia during the early days of the Palmyrene Empire (because of this, he is often called Zabdas the Younger to avoid confusion with his more famous ancestor). With the crucial fortress of Nisibis still under enemy control, Ardashir knew that it would only be a matter of time before the invaders reached the walls of the capital, and he marched north with a force of roughly equal size and strength to that of his foe to prevent that.

The battle took place on the town of Misiche, not far from Ctesiphon and right next the Euphrates, which guarded the left and right flanks of the Iranian and Palmyrene armies, respectively, and was a brutal, indecisive slogging match that displayed the strengths and weaknesses of both armies, even though Zabdas was forced to withdraw due to the casualties his ranks endured. As for Ardashir, although he was in control of the battlefield, he had very few reasons to celebrate: his heavy cataphract cavalry performed magnificently and easily wiped out their opposition, but his infantrymen, despite no longer being the ragged levies in which his ancestors relied on thanks to the reforms made by his father Hormizd I, was still vastly inferior in quality to that of their Syrian opposition, which resembled Roman legionaries of old. Because of this, the Iranian infantry suffered great casualties, and they were thus unable to properly coordinate with the cataphracts and completely envelop Zabdas' forces.

Denied a great victory in the battlefield, Ardashir was still determined to prevent the Palmyrene general from returning to the safety of Nisibis, so he had his horsemen harass his retreating enemy while the bulk of his army followed them closely, waiting for the perfect opportunity to strike. That chance finally materialized itself near the ruined trading center of Hatra, and this time the Syrians were nowhere near ready to fight. Worn down by repeated horse archer attacks, the exhausted Zabdas had ordered his soldiers on a forced march, desperate to avoid another battle. Ironically, this only sealed their fate, with Zabdas being pierced in the chest by an Iranian kontos (spear) and later being beheaded, while the soldiers who weren't killed in the carnage were taken prisoner and deported to various provinces of Iran, as was custom.

This decisive victory was the first one in the long confrontation between Iran and Palmyra, and shattered the myth of Syrian invincibility, born from Odainat's great victories decades ago. With at least half of all of Palmyra's soldiers either dead or captured, along with a member of one of its most important military families, the King of Kings easily occupied Nisibis shortly after and from there subjugated Armenia without great difficulties, finally restoring the empire that had been so carefully built by Shapur I. At last, Mesopotamia was safe from western attacks. Ardashir would spend the rest of 332 AD in Nisibis, gathering as many soldiers as he could for a massive offensive aimed at Syria.

Ardashir killing Zabdas. It is more likely that the Palmyrene general was killed by an ordinary cataphract.

Meanwhile, in Palmyra, the news of what happened at Hatra caused great panic and turmoil among the court and ordinary people alike. There were fears that a military coup was about to take place, an eerie spectre of what truly killed the Old Roman Empire in the third century. Although Zenobius almost fled the capital, fearing for his life, he was convinced that such a drastic action would have catastrophic consequences for the morale of the remaining soldiers (2). However, a growing number of people, including the powerful general Lucius Zabbai (a descendant of Zabbai, another one of Odainat and Zenobia's commanders), who was now the empire's foremost military official thanks to Zabdas' death, were questioning whether or not their king was worth defending.

The Iranian conquest of Syria began in February 333 AD with a march into Edessa, which fell without a siege thanks to the actions of a deserter. With the province of Osroene completely occupied, Ardashir was in striking distance of the Palmyrene capital, by now right to the south of his army, and Lucius scrambled together all of the soldiers that he had left to prevent the Shah from attacking the very heart of Syria. However, instead of doing as expected, Ardashir ignored the Palmyrene army completely and marched west, intending to capture the great city of Antioch and split the enemy empire in two halves, rather than waste his soldiers on a long siege of its capital. Because this move was so unexpected, he crossed the Euphrates with no resistance (an ambush here would have been disastrous) and captured Hierapolis before continuing his westward advance.

Aware that the loss of Antioch would be a catastophe, Zabbai had no choice but to play right into the Shahanshah's hands and march north, encountering his foe on the open fields near Beroea (3). The result of battle that took place there was guaranteed from its very conception: without any rivers or hills to hinder their movement, the Iranian cataphracts easily smashed through the flanks of the Palmyrene forces and inflicted horrific casualties upon them, trampling the unfortunate men whose heads weren't smashed with their maces or impaled by their spears. The footmen, meanwhile, managed to hold their adversaries in place at great cost, with many losing limbs and eventually their lives to the Syrian swords, while the horse archers expertly shot at their enemies from afar with great accuracy, creating a horrible rain of chaos and death that consumed all who came near it.

Ardashir II being blessed by Mithra (left) and Ahura Mazda (right) after his victory at Beroea.

By the time the Battle of Beroea was over, the Iranian army was beaten, tired and bloodied. The Palmyrene one, however, was in ruins. Zabbai had barely escaped with his life, running back to the capital as fast as he and his fellow survivors (12.000 men out of an army that had around 75.000 soldiers) possibly could. Ardashir, meanwhile, celebrated what would become the greatest victory in his career with his soldiers and nobles, and a few days later marched into Antioch, which surrendered to him with no resistance. With the once invincible Palmyrene army destroyed as a fighting force, the Iranians marched south and spread their forces all over Syria, hoping to prevent Zenobius from fleeing to Egypt and therefore decapitate the enemy with a single blow. Little did they know that by the time they finally reached the walls of Palmyra in early April, the king of the city was long dead, having been thrown out of his palace by Zabbai's troops and then lynched by an angry mob, bringing the dynasty created by Odainat to an end.

Unaware of that, Ardashir reached the walls of Palmyra and quickly surrounded the great city, which to his amazement also surrendered with no resistance. Expecting a fierce battle, he was obviously pleased to be proven wrong, but was not so pleased when he heard of king Zenobius' fate. He had hoped to bring the Syrian king back to Ctesiphon in chains, a grand statement that the Palmyrene Empire was truly over, and show to the people of his capital that Iran had taken back its rightful place as the master of the Middle East. Instead, he would be forced to quash several spots of resistance, and worse than that, he received news that the man behind the regicide, Lucius Zabbai, had run away to Egypt before he could be caught, and was probably in Alexandria by now, something that infuriated him (4).

Ardashir's conquest of the Levant was vastly different from the one led by Shapur I almost a century ago. He strictly ordered his soldiers not to engage in any looting or other barbarous acts, and few, if any, cities were sacked, while his ancestor eagerly pillaged as much wealth and deported as many people to the east as he could. This approach was taken probably not out of humanity or kindness, but rather to minimize resistance among the conquered peoples, who were certainly much less willing to revolt if their new overlord didn't destroy the places where they lived and killed their loved ones. However, this conquest was not complete, and the important island city of Tyre, right on the coast of Phoenicia, refused to surrender to the Iranians. Since the Shahanshah wasn't going to acquire a decent fleet for his realm so soon, Tyre would remain a dangerous spot of resistance to Iranian rule for many years, as well as a place from which the Palmyrene navy could launch raids against the Levantine coast.

Unfortunately, Palmyra itself was exempt from Ardashir's magnanimity. In what became one of the most well documented cases of ethnic cleansing of its time, the entire population of over 200.000 people was forcibly deported to places as distant as Khorasan, Khuzestan and Daylam, Nearly all of the buildings were torn apart until only their very foundations were left, the few remaining ones standing eerily like skeletons among the desert sands, and all records and literary works were burned, erasing the very idea that the city had once been a prosperous capital of what was, for a comparatively short time, one of the most powerful empires in the world. Priceless books that were focused on many things, such as nature and philosophy, were torn to pieces, with their covers being used as sandals, and every single valuable sculpture, artwork or jewelry that couldn't be transferred back to Ctesiphon was destroyed (5). The destruction of Palmyra would haunt his legacy, much like the fate of Persepolis haunted that of Alexander the Great.

The Palmyrene Empire had ceased to exist. Although Ardashir desired to conquer Egypt as fast as possible and bring the great city of Alexandria to heel, he was forced to spend the rest of the year in Antioch, from where he organized the administration of Syria, its division into multiple provinces and appointing nobles and bureaucrats who could properly tax the subjugated territories. Vast estates that belonged to prominent Palmyrene aristocrats were redistributed to Iranian nobles, with the biggest and most profitable bits being given to members of the Seven Great Houses.

By early 334, the King of Kings could no longer resist the temptarion of conquering the Jewel of the Nile. In February, he departed Ascalon, on the coast of Palestine, at the head of an army of 50.000 men accompanied by several siege engines, dead set on besieging and capturing Alexandria along with any other cities that dared to oppose him. After crossing the harsh desert of the Sinai (losing a fair amount of men to the heat and thirst) the Iranians occupied the strategic fortress of Pelusium, rightfully portrayed as the gateway to the Nile Delta and beyond, which was abandoned by the time the army of the Shahanshah captured it. From there, Ardashir and his remaining soldiers marched towards Heliopolis, and from there prepared to cross the great river.

As he watched his men build a great pontoon bridge across the Nile, Ardashir was almost literally jumping from joy. He could already see the walls of Alexandria buckling under the power of his army and its weapons, and the massive amount of riches that he would gain from this victory. All he needed to do was cross this single bridge, and, from this simple action, the great empire of the Achaemenids would be restored, the greatest ambition of the members of the House of Sasan.

Just this one bridge.

As he walked forward into a future of eternal glory for himself, his country and his descendants, he failed to notice that the mood of the men around him slowly changed from happy to worried, and from there to absolutely terrified. It was only when the people began to run and bump into each other, desperate to get out of the bridge, that he noticed what was happening. When he finally realized what was going on, he was dumbstruck. The wooden bridge on which he was standing on was being consumed by a raging inferno, and was on the verge of falling apart. What kind of idiot would carry a lit torch into such a massive structure made out of wood in broad daylight?

The King of Kings had very little time to ponder or even run away to safety when the boards over which he was standing on, weakened by the fire, crumbled underneath him, and the monarch fell on the waters of the great river below him. As Ardashir looked to where he was falling, he couldn't believe what was happening before his eyes. It all seemed like a terrible nightmare, a punishment from Ahura Mazda himself for his insatiable ambition, or perhaps a warning. But no, what was happening before his very eyes was absolutely real.

The Nile was burning. Not the vegetation on its banks, no, the water itself was on fire. Soon, the flames reached and engulfed him in their murderous embrace. As he came into contact with it and every moment of his short life flashed before his eyes, he realized that what he came into contact with wasn't normal fire, but rather a horrible substance that burned its way through the water, some sort of sticky mixture that he couldn't free himself of, despite his best efforts, for as he tried to put it out with the abundant water around him, the flames that were searing through his armor and cooking his skin and flesh only grew in size and intensity (6).

The last thing Ardashir II saw before he drew his last breath was his precious bridge collapsing entirely.

He was just 32 years old.

------------------

Notes:

(1) That's actually Shapur II, one of the Sasanian Empire's greatest rulers.

(2) That's going to be one of this ATL's AH.com's most discussed potential PODs: WI Zenobius fled to Egypt?

(3) Modern day Aleppo.

(4) Ardashir hated usurpers.

(5) No way someone can challenge the rule of the King of Kings after seeing what happened to Palmyra. Right? Right...

(6) Ladies and Gentlemen, behold the power of Greek Fire.