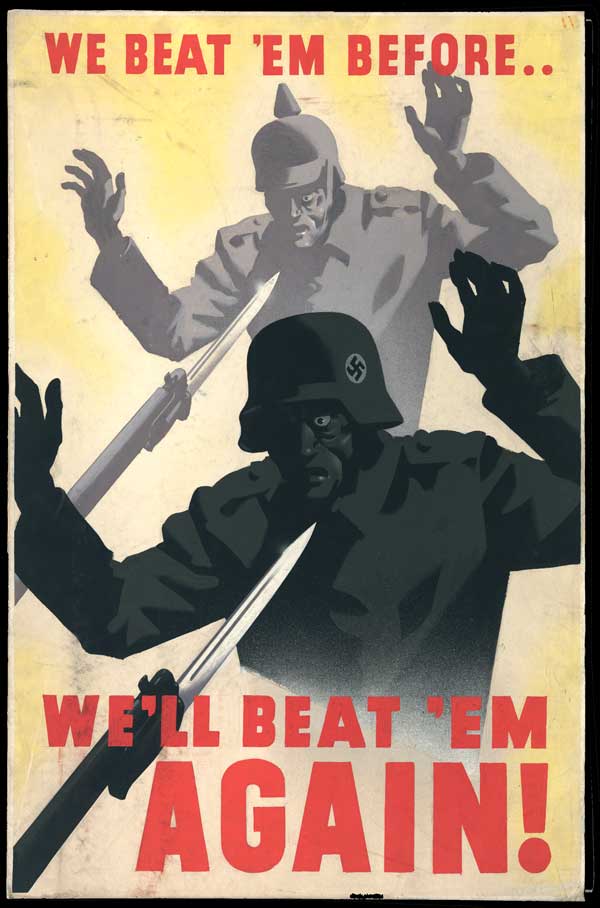

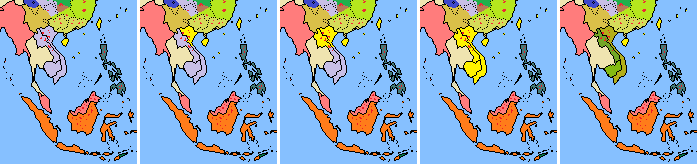

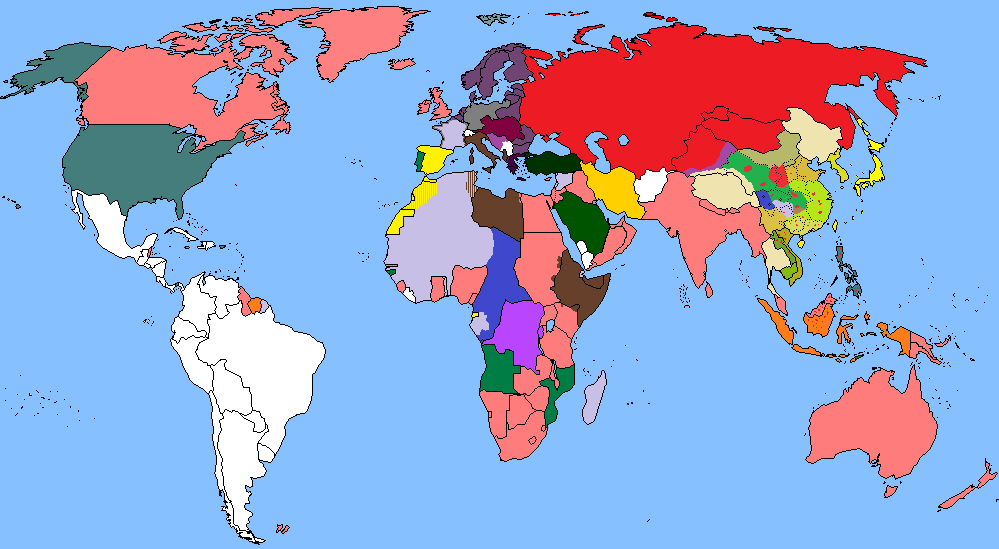

Chapter 38: The Co-Prosperity Sphere liberates Indochina:

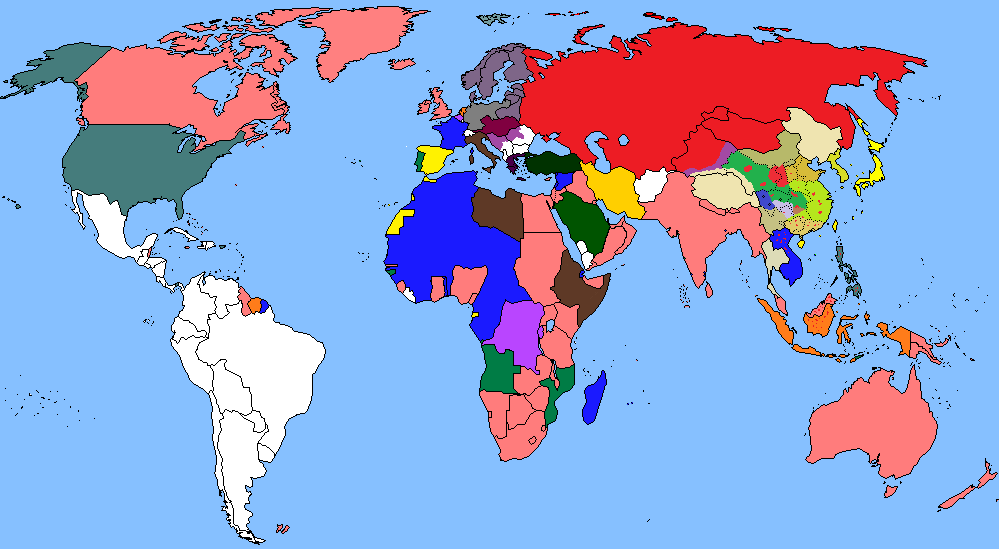

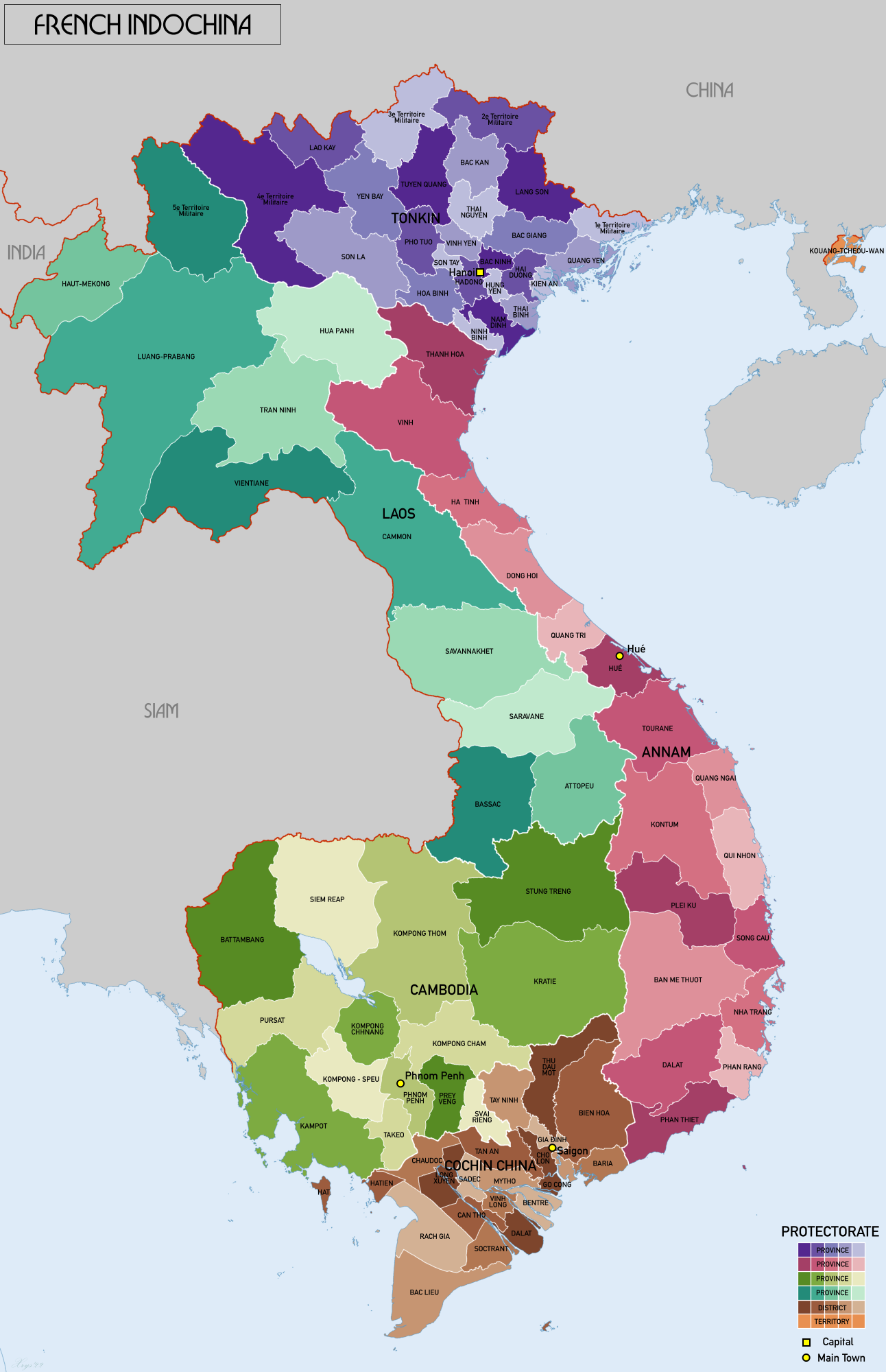

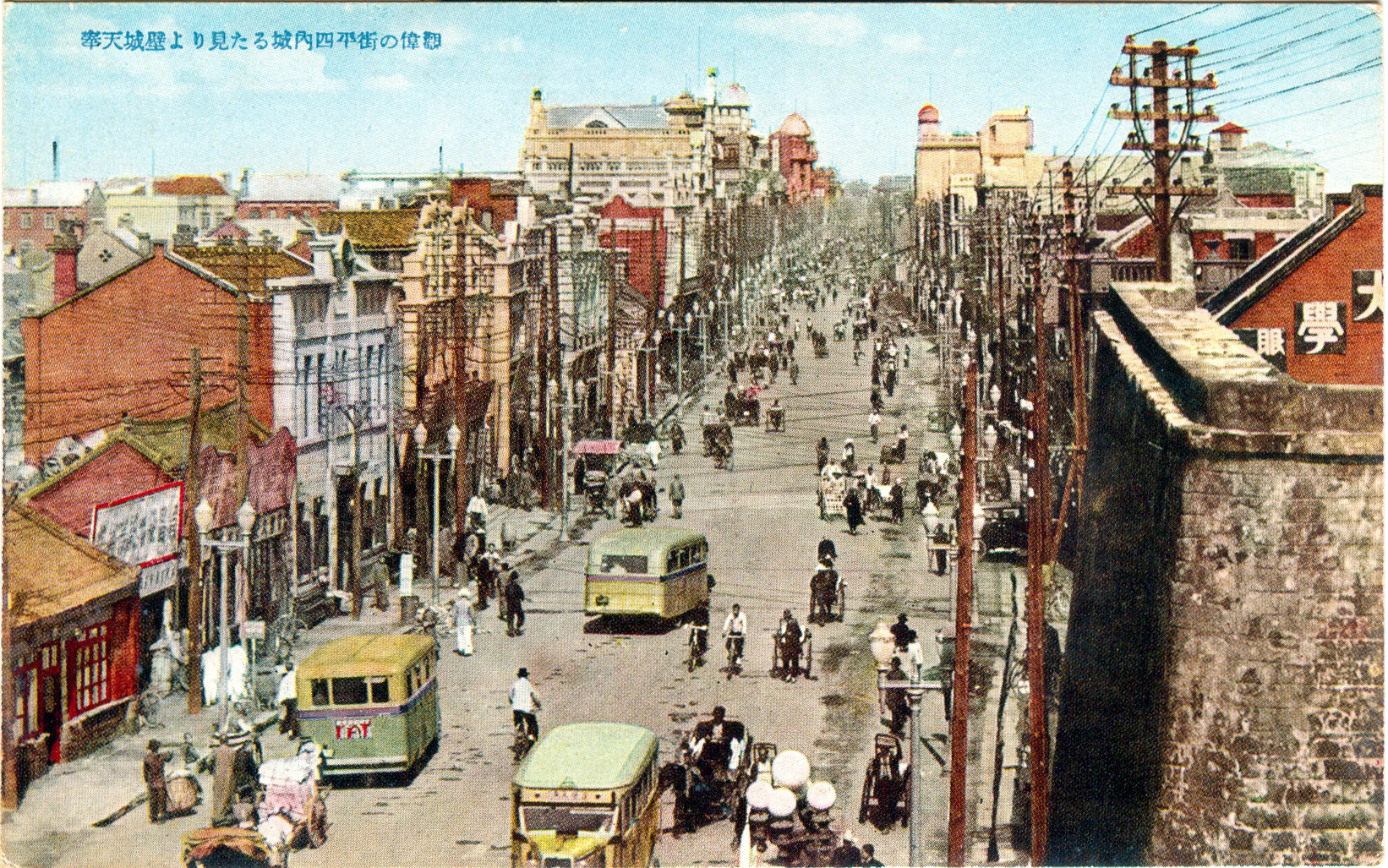

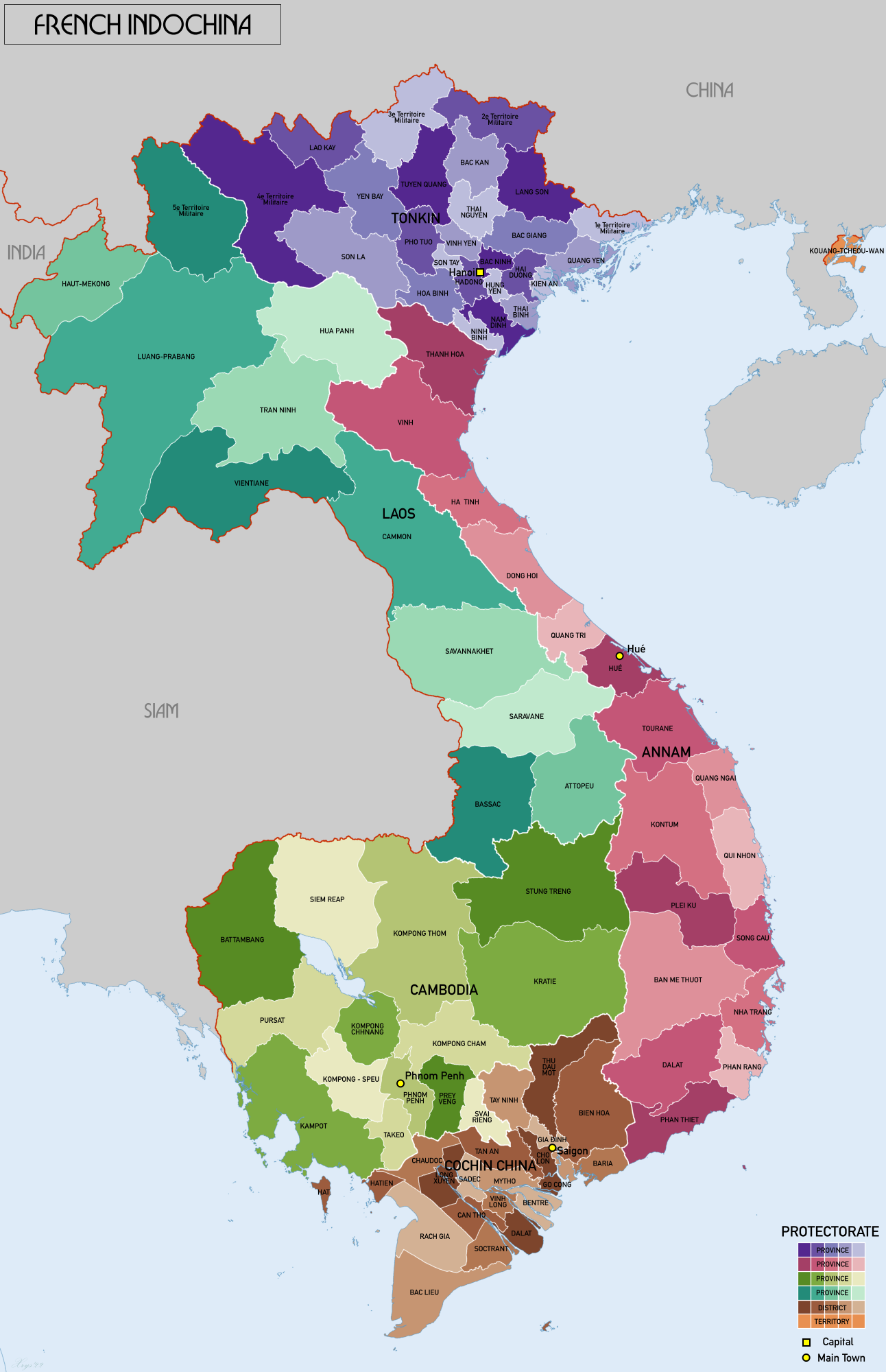

In 1940, France was swiftly defeated by the German Empire, and colonial administration of French Indochina (modern-day Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia) passed to the pro-German French monarchist-fascist government. Later that year, the Vichy government ceded control of Hanoi and Saigon to Japan and control of Saigon and in 1941, Japan extended its control over the whole of French Indochina. The United States, concerned by this expansion, put embargoes on exports of steel and oil to Japan. The desire to escape these embargoes and become resource self-sufficient ultimately led to Japan's decision to go to war against the colonial powers. Indochinese Communists later as a part of the Allied fighting against the Japanese and the Co-Prosperity Sphere , formed a nationalist resistance movement, the Dong Minh Hoi (DMH); this included Communists, but was not controlled by them. When this did not provide the desired intelligence data, they released Ho Chi Minh from jail, and he returned to lead an underground centered on the Communist Viet Minh. This mission was assisted by Western intelligence agencies, including the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Free French intelligence later also tried to affect developments in the fascist French-Japanese collaboration. Throughout East and Southeast Asia, tensions had been building between 1937 and 1941, as Japan and the Co-Prosperity Sphere expanded into China. Franklin D. Roosevelt regarded this as an infringement on U.S. interests in China. The U.S. had already accepted an apology and indemnity for the Japanese bombing of the USS Panay, a gunboat on the Yangtze River in China. In the year 1938 the French Popular Front fell, and the Indochinese Democratic Front went underground. When a new French government, still under the Third Republic, formed in August 1938, among its principal concerns were security of metropolitan France as well as its empire. Among its first acts was to name General Georges Catroux governor general of Indochina. He was the first military governor general since French civilian rule had begun in 1879, following the conquest starting in 1858, reflecting the single greatest concern of the new government: defense of the homeland and the defense of the empire. Catroux's immediate concern was with Japan and the Co-Prosperity Sphere , who were actively fighting in nearby China. In 1939 both the French and Indochinese Communist parties (because of heavy Soviet Union sponsoring and involvement) were outlawed, leading to fewer supplies for Chiang's United Front by the French while at the same time communist rebels started their guerrilla war in Indochina. They were secretly supported by the Japanese across the Nishimura Trail (named after Lieutenant General Takuma Nishimura the later leader of the Indochina Expeditionary Army).

After the defeat of France, with an armistice on June 22, 1940, roughly two-thirds of the country was put under direct German military control. The remaining part of France, and the French colonies, were under a nominally independent government, headed by the First World War hero, Marshal Philippe Pétain. Japan, not directly allied with the German Empire or the Axis Central Powers, asked for German help in stopping supplies going through Indochina to China.Catroux, who had first asked for British support, had no source of military assistance from outside France, stopped the trade to China to avoid further provoking the Japanese. A Japanese verification group, headed by Takuma Nishimura entered Indochina on June 25. These Indochina Expeditionary Army claimed to root out communist rebels that operated across the border from Indochina to attack the Co-Prosperity Sphere. On the same day that Nishimura arrived, Fascist France dismissed Catroux, for independent foreign contact. He was replaced by Vice AdmiralJean Decoux, who commanded the French naval forces in the Far East, and was based in Saigon. Decoux and Catroux were in general agreement about policy, and considered managing Nishimura the first priority. Decoux had additional worries. The senior British admiral in the area, on the way from Hong Kong to Singapore, visited Decoux and told him that he might be ordered to sink Decoux's flagship, with the implicit suggestion that Decoux could save his ships by taking them to Singapore, which appalled Decoux. While the British had not yet attacked French ships that would not go to the side of the Allies, that would happen at Mers-el-Kébir in North Africa within two weeks; Decoux did not arrive in Hanoi until July 20, while Catroux stalled Nishimura on basing negotiations, also asking for U.S. Help.

Reacting to the initial Japanese presence in Indochina, on July 5, the U.S. Congress passed the Export Control Act, banning the shipment of aircraft parts and key minerals and chemicals to Japan, which was followed three weeks later by restrictions on the shipment of petroleum products and scrap metal as well. Decoux, on August 30, managed to get an agreement between the French Ambassador in Tokyo and the Japanese Foreign Minister, promising to respect Indochinese integrity in return for cooperation against China. Nishimura, on September 20, gave Decoux an ultimatum: agree to the basing, or the 5th Division, known to be at the border, would enter. Japan entered Indochina on September 22, 1940. An agreement was signed, and promptly violated, in which Japan promised to station no more than 6,000 troops in Indochina, and never have more than 25,000 transiting the colony. Rights were given for three airfields, with all other Japanese forces forbidden to enter Indochina without Vichy consent. Immediately after the signing, a group of Japanese officers, in a form of insubordination not uncommon in the Japanese military, attacked the border post of Dong Dang, laid siege to Lam Son, which, four days later, surrendered. There had been 40 killed, but 1,096 troops had deserted. With the signing of the Tripartite Pact on September 27, 1940, creating the Axis Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Fascist France and Italy, Decoux had new grounds for worry: the Germans could pressure the homeland to support their far-east ally, Japan. Japan apologized for the Lam Song incident on October 5. Decoux relieved the senior commanders he believed should have anticipated the attack, but also gave orders to hunt down the Lam Song deserters, as well as Viet Minh who had expanded their operations in Indochina while the French seemed preoccupied with Japan. The fight against the Viet Minh was the official motivation for Co-Prosperity Sphere troops in Indochina. Through the next months, the French colonial government had largely stayed in place, as the Fashist French government was on reasonably friendly terms with Japan. Still they denied any further influence and control for the Japanese and even declined their offer to buy Indochina. But with the Indochina nationalist rebellions in 1940 this all changed.

The Japanese invasion of French Indochina (仏印進駐 Futsu-in shinchū) itself was a short undeclared military confrontation between the Empire of Japan and Fascist France in northern Indochina. Fighting lasted from 22 to 26 September 1940. Although an agreement had been reached between the French and Japanese governments prior to the outbreak of fighting, authorities were unable to control events on the ground for several days before the troops stood down. Per the prior agreement, Japan was allowed to occupy Tonkin in northern Indochina and effectively blockade the are for Communist Rebels and supplies for the Chinese United Front. In early 1940, troops of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) moved to seize southern Guangxi and Langzhou County, where the eastern branch of the Kunming–Hai Phong Railway reached the border at the Friendship Pass in Pingxiang. They also tried to move west to cut the rail line to Kunming. The railway from Indochina was the Chinese government's last secure overland link to the outside world. In May 1940, Germany invaded France. On 22 June, France signed an armistice with Germany (in effect from 25 June). On 10 July, the French parliament voted full powers to Marshal Philippe Pétain, effectively abrogating the Third Republic for a new aristocratic, fascist France. Although much of metropolitan France came under German occupation while governed by Pétain's government, the French colonies remained under the direct control of Pétain's government at German occupied Paris. Resistance to Pétain and the armistice began even before it was signed, with Charles de Gaulle's appeal of 18 June. As a result, a de facto government-in-exile in opposition to Pétain, called Free France, was formed in London.

On 19 June, Japan took advantage of the defeat of France and the impending armistice to present the Governor-General of Indochina, Georges Catroux, with a request, in fact an ultimatum, demanding the closure of all supply routes to China and the admission of a 40-man Japanese inspection team under General Takuma Nishimura. The Free French and the Americans became aware of the true nature of the Japanese "request" through intelligence intercepts, since the Japanese had informed their German allies. Catroux initially responded by warning the Japanese that their unspecified "other measures" would be a breach of sovereignty. He was reluctant to acquiesce to the Japanese, but with his intelligence reporting that Japanese army and navy units were moving into threatening positions, the French government was not prepared for a protracted defense of the colony. Therefore, Catroux complied with the Japanese ultimatum on 20 June. Before the end of June the last train carrying munitions crossed the border bound for Kunming.

Following this humiliation, Catroux was immediately replaced as governor-general by Admiral Jean Decoux. Although Catroux could have tried to remain in his post and rally the colony to de Gaulle's movement, he chose to step aside. He did not return to France, however, but to London. On 22 June, while Catroux still remained in his post, the Japanese issued a second demand: naval basing rights at Huangzhouwan and the total closure of the Chinese border by 7 July. Takuma Nishimura, who was to lead the "inspection team", the true purpose of which was unknown, even to many Japanese, arrived in Hanoir on 29 June. On 3 July, he issued a third demand: air bases and the right to transit combat troops through Indochina. These new demands were referred to Fashist France. The incoming governor, Decoux, who arrived in Indochina in July, urged the government to reject the demands. Although he believed that Indochina could not defend itself against a Japanese invasion, Decoux believed it was strong enough to dissuade Japan from invading. In Vichy, General Jules-Antoine Bührer, chief of the Colonial General Staff, counselled resistance. The United States had already been contracted to provide aircraft, and there were 4,000 Tirailleurs sénégalais in Djibouti that could be shipped to Indochina in case of need. In Indochina, Decoux had under his command 32,000 regulars, plus 17,000 auxiliaries, although they were all ill-equipped.

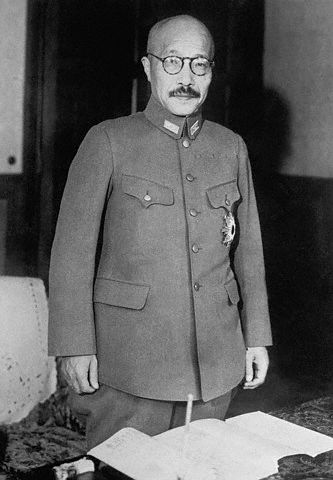

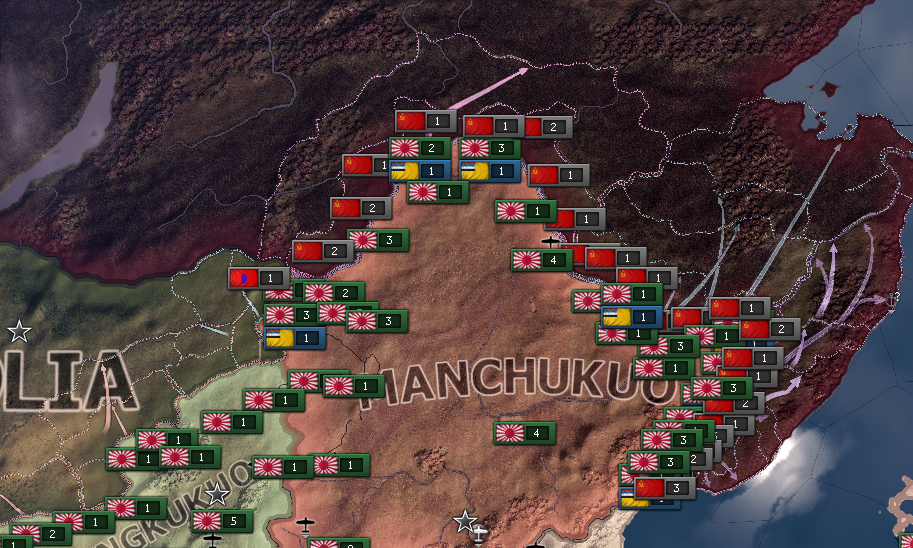

On 30 August 1940, the Japanese foreign minister, Yosuke Matsuoka, approved a draft proposal submitted by his French colleague, Paul Baudoin, whereby Japanese forces could be stationed in and transit through Indochina only for the duration of the Sino Civil War that involved the Japanese and the Co-Prosperity Sphere states. Both governments then "instructed their military representatives in Indochina to work out the details although they would have been better advised to stick to Tokyo–Fascist French channels a bit longer". Negotiations between the supreme commander of Indochinese troops, Maurice Martin, and General Nishihara began at Hanoi on 3 September. During negotiations, the government in occupied france asked the German government to intervene to moderate its ally's demands. The Germans did not do anything. Decoux and Martin, acting on their own, looked for help from the American and British consuls in Hanoi, and even consulted with the Chinese government on joint defense against a Japanese attack on Indochina if possible. On 6 September, an infantry battalion of the Japanese Twenty-Second Army based in Nanning violated the Indochinese border near the French fort at Dong Dang. The Twenty-Second Army was a part of the South China Army (2nd National Chinese Army), whose officers, remembering the Mukden incident of 1931, were trying to force their superiors to adopt a more aggressive policy. Following the Dong Dang incident, Decoux cut off negotiations. On 18 September, Nishihara sent him an ultimatum, warning that Japanese troops would enter Indochina regardless of any French agreement at 2200 hours (local time) on 22 September. This prompted Decoux to demand a reduction in the number of Japanese troops that would be stationed in Indochina. The Japanese Army General Staff, with the support of the South China Army, was demanding 25,000 troops in Indochina. Nishihara, with the support of the Imperial General Headquarters, got that number reduced to 6,000 on 21 September.

Seven and a half hours before the expiration of the Japanese ultimatum on 22 September, Martin and Nishihara signed an agreement authorising the stationing of 6,000 Japanese troops in Tonkin north of the Red River, the use of four airfields in Tonkin, the right to transit up to 25,000 troops through Tonkin to Yunnan and the right to transit one division of the Twenty-Second Army through Tonkin via Haiphong for use elsewhere in China together with the allowance to fight the Viet Minh. Already on 5 September, the South China Army had organized the amphibious Indochina Expedition Army under Major-General Takuma Nishimura, it was supported by a flotilla of ships and aircraft, both carrier- and land-based. When the accord was signed, a convoy was waiting off Hainan Island to bring the expeditionary force to Tonkin. The accord had been communicated all relevant commands by 2100 hours, an hour before the ultimatum was set to expire. It was understood between Martin and Nishimura that the first troops would arrive by ship. The Twenty-Second Army, however, did not intend to wait to take advantage of the accord. Lieutenant-General Akihito Nakamura, commander of the 5th (Infantry) Division, sent columns across the border near Đồng Đăng at precisely 2200 hours. At Đồng Đăng there was an intense exchange of fire that quickly spread to other border posts overnight. The French position at the railhead at Lang Son was surrounded by Japanese armour and forced to surrender on 25 September. Before surrendering, the French commanders had ordered the breechblocks of the 155mm cannons thrown into a river to prevent the Japanese from re-using them. During the Sino-French War of 1884–5, the French had been forced into an embarrassing retreat from Lang Son in which equipment had likewise been thrown into the same river to prevent capture. When the breechblocks of 1940 were eventually retrieved, several chests of money lost in 1885 were found also. Among the units taken captive at Lạng Sơn was the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Foreign Infantry Regiment, marking perhaps the first time a Foreign Legion unit had surrendered without a fight. The 2nd Battalion contained 179 German and Austrian volunteers, whom the Japanese in vain tried to induce to change sides. On 23 September, Fashist France protested the breach of the agreements by the IJA to the Japanese government.

On the morning of 24 September, Japanese aircraft from aircraft carriers in the Gulf of Tonkin attacked French positions on the coast. A Vichy envoy came to negotiate; in the meantime, shore defenses remained under orders to open fire on any attempted landing. On 26 September, Japanese forces came ashore at Dong Tac south of Haiphong, and moved on the port. A second landing put tanks ashore, and Japanese planes bombed Haiphong, causing some casualties. By early afternoon the Japanese force of some 4,500 troops and a dozen tanks were outside Haiphong. By the evening of 26 September, fighting had died down. Japan took possession of Gia Lam Airbase outside Hanoi, the rail marshaling yard on the Yunnan border at Lao Cai and Phu Lang Thoung on the railway from Hanoi to Lạng Sơn, and stationed 900 troops in the port of Haiphong and 600 more in Hanoi.

The occupation of southern Indochina did not happen immediately. However, the Vichy government had agreed that some 40,000 troops could be stationed there. However, Japanese planners did not immediately move troops there, worried that such a move would be inflammatory to relations between Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Furthermore, within the Japanese high command there was a division about what to do about the still remaining Soviet threat to the north of their Manchurian and Mengjiang territories. Because the Europeans were focused on the conflict in Europe and it was unlikely that Fascist France or Great Britain would send help, some 140,000 Japanese troops invaded southern Indochina on 28 July 1941. French troops and the civil administration were allowed to remain, albeit under Japanese supervision for a few months until the Indochina nationalist rebellions in 1940.

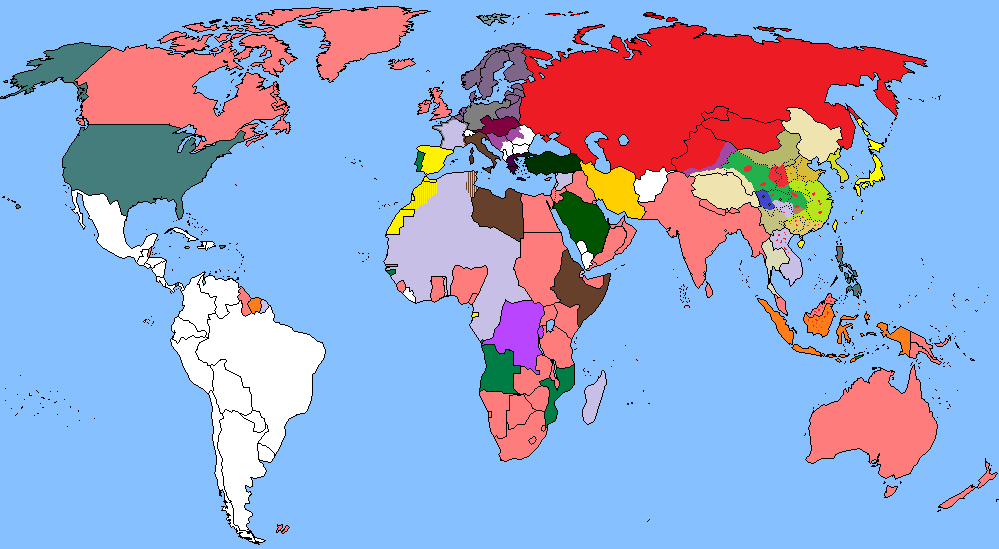

The Japanese coup d'état in French Indochina, known as Meigo Sakusen (Operation Bright Moon),was a Japanese operation that took place during the 1940 Indochina Nationalist Rebellions. With Japan and the Co-Prosperity Sphere already escalating the conflict in China and Indochina the Americans had started a full embargo of much needed resources and a conflict seamed unavoidable. The Japanese tried to use the German Empire's advance trough the Dutch Homeland to force the Dutch East Indies to allow them to buy their resources there cheaply but were refused. Angered and blinded by their own propaganda the Japanese believed that the Dutch Colony only dared to do so because of a secret alliance with Britain and America to strangle the Co-Prosperity Sphere with a trade blockade. This lead to the ultimate decision to attack the colonial powers and to take full direct control of all of Indochina. The Japanese quickly struck in a military campaign attacking garrisons all over the colony. The French were caught off guard and all of the garrisons were overrun with some then having to escape to nearby Siam where they were harshly interned. The Japanese replaced French officials, and effectively dismantled their control of Indochina. The Japanese were then able to install and create a new Empire of Vietnam, Kingdom of Cambodia and Kingdom of Laos wich under their direction would become a part of the Co-Prosperity Sphere.

At this time the French Indochina army still outnumbered the Japanese and comprised about 65,000 men, of whom 48,500 were locally recruited Trailleurs indochinous under French officers. The remainder were French regulars of the Colonial Army plus three battalions of the Foreign Legion. A separate force of indigenous gardes indochinois (gendarmerie) numbered 27,000. Since the fall of Franse, in June 1940 no replacements or supplies had been received from outside Indochina. During the time of the Japanese coup only 30,000 French troops could be described as fully combat ready, the remainder serving in garrison or support units. At the beginning of the coup the understrength Japanese Indochina Expedition Army was composed of 30,000 troops a force that was substantially increased by 25,000 reinforcements brought in from China (both Japanese and other members of the Co-Prosperity Sphere) in the following months. Japanese forces then were redeployed around the main French garrison towns throughout Indochina, linked by radio to the Southern area headquarters. French officers and civilian officials were however forewarned of an attack through troop movements, and some garrisons were put on alert. The Japanese envoy in Saigon Ambassador Shunichi Matsumoto declared to Decoux that since the Indochina National Revolt no one could deny that the citizens of Indochina wished to be liberated as independent states that would became a part of the Co-Prosperity Sphere. Decoux however resisted stating that this would be a catalyst for an Allied counter reaction, most likely a invasion but suggested that Japanese control would be accepted if they actually invaded. This was not enough and the Tsuchihashi accused Decoux of playing for time. A few days later, after more stalling by Decoux, Tsuchihashi delivered an ultimatum for French troops to disarm. Decoux sent a messenger to Matsumoto urging further negotiations but the message arrived at the wrong building. Tsuchihashi, assuming that Decoux had rejected the ultimatum, immediately ordered commencement of the coup.

That evening Japanese forces moved against the French in every center. In some instances French troops and the Garde Indochinoise were able to resist attempts to disarm them, with the result that fighting took place in Saigon, Hanoi, Haiphong, Nha Tran and the Northern frontier, but most native colonial troops openly joined the Japanese and the Co-Prosperity Sphere. Japan issued instructions to the government of Thailand to seal off its border with Indochina and to arrest all French and Indochinese residents within its territory. Instead, Thailand began negotiating with the Japanese over their course of action, and by the end of March they hadn't fully complied with the demands. Domei Radio (the official Japanese propaganda channel) announced that pro-Japanese independence organizations in Hué formed a federation to promote a free Indochina and cooperation with the Japanese.

The 11th R.I.C (régiment d'infanterie coloniale) based at the Martin de Pallieres barracks in Saigon were surrounded and disarmed after their commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Moreau, was arrested. In Hué there was only sporadic fighting; the Garde Indochinoise, who provided security for the résident supérieur, fought for 19 hours against the Japanese before their barracks was overrun and destroyed. Three hundred men, one third of them French, managed to elude the Japanese and escape to the A Sáu Valley. However, over the next three days, they succumbed to hunger, disease and betrayals - many surrendered while others fought their way into Laos where only a handful survived. Meanwhile, Mordaunt led opposition by the garrison of Hanoi for several hours but was forced to capitulate. In Annam and Cochinchina only token resistance was offered and most garrisons, small as they were, surrendered. Further north the French had the sympathy of many indigenous peoples. Several hundred Laotians volunteered to be armed as guerrillas against the Japanese; French officers organized them into detachments but turned away those they did not have weapons for. In Haiphong the Japanese assaulted the Bouet barracks: headquarters of Colonel Henry Lapierre's 1st Tonkin Brigade. Using heavy mortar and machine gun fire, one position was taken after another before the barracks fell and Lapierre ordered a ceasefire. Lapierre refused to sign surrender messages for the remaining garrisons in the area. Codebooks had also been burnt which meant the Japanese then had to deal with the other garrisons by force. In Laos, Viantiane, Thakhek and Luang Prabang were taken by the Japanese without much resistance. In Cambodia the Japanese with 8,000 men seized Phnom Penh and all major towns in the same manner. All French personnel in the cities on both regions were either interned (and forced to work for the newly independent states later, or in some cases executed. The Japanese strikes at the French in the Northern Frontier in general saw the heaviest fighting. One of the first places they needed to take and where they amassed the 22nd division was at Lang Son, a strategic fort near the Chinese border. The coup had, in the words of diplomat Jean Sainteny, "wrecked a colonial enterprise that had been in existence for 80 years."

French losses were heavy – in total 15,000 French soldiers were held prisoner by the Japanese. Nearly 4,200 were killed with many executed after surrendering - about half of these were European or French metropolitan troops. Practically all French civil and military leaders as well plantatio owners were made prisoners, including Decoux. They were confined either in specific districts of big cities or in camps. Those who were suspected of armed resistance were jailed in the Kempeitai prison in bamboo cages and were tortured and cruelly interrogated. The locally recruited tirailleurs and gardes indochinois who had made up the majority of the French military and police forces, effectively ceased to exist. About a thousand were killed in the fighting or executed after surrender. Most quikly joined pro-Japanese militias and were later reused by the newly formed independent states of the Co-Prosperity Sphere. Deprived of their French cadres, many dispersed to their villages of origin. What was left of the French forces that had escaped the Japanese attempted to join the resistance groups where they had more latitude for action in Laos. The Co-Prosperity Sphere state there had less control over this part of the territory. Elsewhere the resistance failed to materialize as many Indochinese citizens refused to help the French. They also lacked precise orders and communications from the provisional government as well as the practical means to mount any large-scale operations.

In northern Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh's Viet Minh started their own guerilla campaign with the help of the American OSS who trained, supplied them with arms and funds. They established their bases in the countryside without meeting much resistance from the Japanese and their newly formed militias who were mostly present in the cities. A month later OSS with the Viet Minh - some of whom were remnants of Sabattiers division - went over the border to conduct operations. Their actions were limited to a few attacks against Japanese military posts. Most of these were unsuccessful however as the Viet Minh lacked the military force to launch any kind of attack against the Japanese.

Empire of Vietnam (Đế quốc Việt Nam):

The Empire of Vietnam (Vietnamese: Đế quốc Việt Nam; Japanese: ベトナム帝国) was a puppet state of Imperial Japan and a member of the Co-Prosperity Sphere after the Japanese coup in Indochina. During the Second Great War, after the fall of France and establishment of Fashist France, the French had lost practical control in French Indochina to the Japanese, but Japan stayed in the background while giving the Vichy French administrators nominal control for a few mounths. This changed when Japan officially took over after the Indochina Revolt. To gain the support of the Vietnamese people, Imperial Japan declared it would return sovereignty to Vietnam. Emperor Bào Dai declared the Treaty of Hué made with France in 1884 void. Tran Trong Kim, a renowned historian and scholar, was chosen to lead the government as prime minister.

Kim and his ministers spent a substantial amount of time on constitutional matters at their first meeting in Hué in 1940. One of their first resolutions was to alter the national name to Việt Nam. This was seen as a significant and urgent task. It implied territorial unity; "Việt Nam" had been Emperor Gia Long's choice for the name of the country since he unified the modern territory of Việt Nam in 1802. Furthermore, this was the first time that Vietnamese nationalists in the northern, central and southern regions of the country officially recognized this name. In March, activists in the North always mentioned Đại Việt (Great Việt), the name used before the 15th century by the Le Dynasty and its predecessors, while those in the South used Vietnam, and the central leaders used An Nam (Peaceful South) or Đại Nam (Great South, which was used by the Nguyen Lords). Kim also renamed the three regions of the country — the northern (former Tonkin or Bắc Kỳ) became Bắc Bộ, the central region (former Annam or Trung Kỳ) became Trung Bộ, and the southern areas (former Couchinchina or Nam Kỳ) became Nam Bộ. When France had finished its conquest of Vietnam in 1885, only southern Vietnam was made a direct colony under the name of Cochinchina. The northern and central regions were designated as protectorates as Tonkin and Annam. When the Empire of Vietnam was proclaimed, the Japanese retained direct military control of Vietnam as a measure to prevent Colonial Powers to return to the new member state of the Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Thuan Hóa, the pre-colonial name for Huế, was restored. Kim's officials worked to find a French substitute for the word "Annamite", which was used to denote Vietnamese people and their characteristics as described in French literature and official use. "Annamite" was considered derogatory, and it was replaced with "Vietnamien" (Vietnamese). Apart from Thuan Hóa, these terms have been internationally accepted since Kim ordered the changes. Given that the French colonial authorities emphatically distinguished the three regions of "Tonkin", "Annam", and "Cochinchina" as separate entities, implying a lack of national culture or political integration, Kim's first acts were seen as symbolic and the end of generations of frustration among Vietnamese intelligentsia and revolutionaries. Kim quickly selected a new national flag — a yellow, rectangular banner with three horizontal red stripes modeled after the Li Kwai in the Book of Changes — and a new national anthem, the old hymn Dang Dan Cung (The King Mounts His Throne). This decision ended three months of speculation concerning a new flag for Vietnam.

Kim's government strongly emphasised educational reform, focusing on the development of technical training, particularly the use of romanised script (quoc ngu – later japanised) as the primary language of instruction. After less than two months in power, Kim organized the first primary examinations in Vietnamese, the language he intended to use in the advanced tests. Education minister Hoang Xuan Han strove to Vietnamese public secondary education. His reforms took more than four months to achieve their results. A few months later, when the Japanese decided to grant Vietnam full independence and territorial unification, Kim's government was about to begin a new round of reform, by naming a committee to create a new national education system. The Justice minister Trinh Dinh Thao launched an attempt at judicial reform. He created the Committee for the Reform and Unification of Laws in Huế, which he headed. His ministry reevaluated the sentences of political prisoners, releasing a number of anti-French activists and restoring the civil rights of others. This led to the release of a number of Communist cadres who returned to their former cells, and actively participated in actions against Kim's government.

One of the most notable changes implemented by Kim's government was the encouragement of mass political participation. In memorial ceremonies, Kim honoured all national heroes, ranging from the legendary national founders, the Húng kingsto slain anti-French revolutionaries such as Nguyen Thai Hoc, the leader of the Vietnamese Nationalist Party (Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang) who was executed with twelve comrades in 1930 in the aftermath of the Yen Bái mutiny. A committee was organized to select a list of national heroes for induction into the Temple of Martyrs (Nghia Liet Tu). City streets were renamed. In Huế, Jules Ferry was replaced on the signboards of a main thoroughfare by Le Loi, the founder of the Le Dynasty who expelled the Chinese in 1427. General Tran Hung Dao, who twice repelled Mongol invasions in the 13th century, replaced Paul Bert. After that the new mayor of Hanoi, Tran Van Lai, ordered the demolition of French built statues in the city parks in his campaign to Wipe Out Humiliating Remnants. Similar campaigns were enacted in all of Vietnam in following months. Meanwhile, the freedom of the press was instituted, resulting in the publication of the pieces of anti-French movements and critical essays on French collaborators. Heavy criticism was even extended to Nguyen Huu Do, the great grandfather of Bảo Đại who was notable in assisting the French conquest of Dai Nam in the 1880s. Still the new government oppressed communist press and continued to fight the Viet Minh. Kim put particular emphasis on the mobilization of youth. Youth Minister Phan Anh, attempted to centralist and heavily regulate all youth organizations (just like the Japanese and the rest of the Co-Prosperity Sphere) , which had proliferated immediately after the Japanese coup. An imperial order decreed an inclusive, hierarchical structure for youth organizations. At the apex was the National Youth Council, a consultative body, which advised the minister. Similar councils were to be organized down to the district level. Meanwhile, young people were asked to join the local squads or groups, from provincial to communal levels. They were given physical training and were charged with maintaining security in their communes. Each provincial town had a training center, where month-long paramilitary courses were on offer.

The government also established a national center for the Advanced Front Youth (Thanh nien tien tuyen) in Huế. It was inaugurated with the intention of being the centrepiece for future officer training. Later that month, regional social youth centers were established in Hanoi, Huế, and Saigon. In Hanoi, the General Association of Students and Youth (Tong Hoi Sinh vien va Thanh Nien) was animated by the fervor of independence. The City University in Hanoi became a focal point of political agitation. The Kempeitai retaliated, arresting hundreds of pro-communist Vietnamese youths in late June. The most notable achievement of Kim's Empire of Vietnam was the successful negotiation with Japan for the territorial unification of the nation. The French had subdivided Vietnam into three separate regions: Cochinchina (in 1862), and Annam and Tonkin (both in 1884). Cochinchina was placed under direct rule while the latter two were officially designated as protectorates. Immediately after terminating French rule, the Japanese authorities were not enthusiastic about the territorial unification of Vietnam. However, after the formation of Kim's cabinet, Japan quickly agreed to transfer what was then Tonkin and Annam to Kim's authority, although it retained control of the cities of Hanoi, Haiphong and Da Nang. Meanwhile, southern Vietnam remained under direct Japanese control, just as Cochinchina had been under French rule.

Beginning in the same months, Foreign Minister Tran Van Choung negotiated with the Japanese in Hanoi for the transfer of the three cities to Vietnamese rule, the Japanese agreed, but stated that important cities like Hué, Hanoi, Saigon and Haiphong were seen as strategic points in their war effort and should be guarded by Co-Prosperity Sphere forces to secure them against a return of the colonial powers for now . It was after the Vietnamese agreed to this terms that the Japanese allowed the process of national unification to take place. Bảo Đại issued a decree proclaiming the impending reunification of Vietnam. General Yuitsu Tsuchihashi signed a series of decrees transferring some of the duties of the government (including customs, information, youth, and sports) to the governments of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, effective the next months. Bảo Đại then issued imperial orders establishing four committees to work on a new regime: the National Consultative Committee (Hoi dong Tu van Quoc Gia); a committee of fifteen to work on the creation of a constitution; a committee of fifteen to examine administrative reform, legislation, and finance; and a committee for educational reform. For the first time, leaders from southern regions were invited to join these committees too.

Other developments in southern Vietnam in early days of next months were seen as preparatory Japanese steps towards granting territorial reunification to Vietnam. Then, when southern Vietnam was abuzz with the spirit of independence and mass political participation due to the creation of the Vanguard Youth organizations in Saigon and other regional centres, Governor Minoda announced the organization of the Hoi Nghi Nam (Council of "Nam Bo", i.e. Cochinchina) to facilitate his governance. This council was charged with advising the Japanese based on questions submitted to it by the Japanese and for overseeing provincial affairs. Minoda underlined that its primary aim was to make the Vietnamese population believe that they had to collaborate with the Japanese, because "if the Japanese lose the war, the independence of Indochina would not become complete." At the inauguration of the Council of Nam Bo the same months Minoda implicitly referred to the unification of Vietnam. Tran Van An was appointed as the president of the Council, and Kha Vang Can, a leader of the Vanguard Youth, was appointed to be his deputy. Kim then arrived in Hanoi to negotiate directly with Governor-General Tsuchihashi. Tsuchihashi agreed to transfer control of Hanoi, Haiphong, Da Nang and the rest of the Vietnamese territory to Kim's government, taking effect on next months. After protracted negotiation, Tsuchihashi agreed that Nam Bo would be united with the Empire of Vietnam and that Kim would attend the unification ceremonies in Hué. After the creation of the puppet Empire of Vietnam, the Japanese began raising an Imperial Vietnamese Army, to help police the region and lift their own garrison forces and duties to protect the region. The Vietnamese Imperial Army was officially established by the Japanese Indochina Expedition Army to maintain order in the new country. The Vietnamese Imperial Army was under the control of Japanese lieutenant general Yuitsu Tsuchihashi, who served as adviser to the Empire of Vietnam. The Japanese were even lending a few Cruisers and Destroyers (with Japanese officers and captains to the Vietnamese Navy) just like they did for Manchukuo, Chosen, Yankoku and Taikoku so they themselves could build newer models and would still remain officially in the limitations of the London Naval Treatment.

Kingdom of Cambodia (Preăh Réachéanachâk Kâmpŭchéa):

The Japanese liberation of Cambodia marked the independence of the Kingdom of Cambodia when the French protectorate over Cambodia and other parts of Indochina officially ended after the Japanese coup. Cambodia declared itself an independent nation, and the Japanese military presence continued helped to form the new government and a independent Royal Cambodian Army as a member state of the Co-Prosperity Sphere. After the nominal French Indochina colonial government was overthrown, Cambodia became a pro-Tokyo puppet state. After the Franco-Thai War of 1940 the French Indochinese colonial authorities were in a position of weakness. The Fascist French government signed an agreement with Japan to allow the Japanese military transit through French Indochina and to station troops in Northern Vietnam up to a limit of 25,000 men. Meanwhile, the Siam/Thai government, under the pro-Japanese leadership of Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram and strengthened by virtue of its treaty of friendship with Japan, took advantage of the weakened position of France, and invaded Cambodia's western provinces to which it had historic claims. Following this invasion, Tokio hosted the signature of a treaty in that formally compelled the French to relinquish the provinces of Battambang, Siem Reap, Koh Kong as well as a narrow extension of land between the 15th parallel and the Dangrek Mountains in the Stung Treng Province. As a result, Cambodia had lost almost half a million citizens and one-third of its former surface area to Siam/Thailand. After the Imperial Japanese Army entered the French protectorate of Cambodia and established a garrison that numbered 8,000 troops. Despite their military presence, the Japanese authorities allowed Fashist French colonial officials to remain at their administrative posts for now. After a major anti-French demonstration in Phnom Penh after a prominent monk, Hem Chieu, was arrested for allegedly preaching seditious sermons to the colonial militia. The French authorities arrested the demonstration's leader, Pach Chhoeun, and exiled him to the prison island of Con Son. Pach Chhoen was a respected Cambodian intellectual, associated with the Buddhist Institute and founder of Nagaravatta, the first overtly political newspaper in the Khmer language in 1936, along with Sim Var. Another of the men behind Nagaravatta, Son Ngoc Thanh (a Paris-educated magistrate) was also blamed for the demonstration, which the French authorities suspected had been carried out with Japanese encouragement. The Japanese used these demonstrations and independence movement after their coup and eliminated French control over Indochina. The French colonial administrators were relieved of their positions (but sometimes forced to work for the new government), and French military forces were ordered to disarm. The aim was to revive the flagging support of local populations for Tokyo's war effort by encouraging indigenous rulers to proclaim independence.

Young king Norodom Sihanouk proclaimed an independent Kingdom of Kampuchea, following a formal request by the Japanese. Shortly thereafter the Japanese government nominally ratified the independence of Cambodia and established a consulate in Phnom Penh (like they had done in Hué before). The next months king Sihanouk changed the official name of the country in French from Cambodge to Kampuchea. The new government did away with the romanisation of the Khmer language that the French colonial administration was beginning to enforce and officially reinstated the Khmer script. This measure taken by the new governmental authority would be popular and long-lasting. Pro-japanese Son Ngoc Thanh returned to Cambodia during the next months. He was initially appointed foreign minister and would become Prime Minister two months later. The Cambodian puppet state of Japan then became a member state of the Co-Prosperity Sphere. The Japanese helped to build the Royal Kampuchea Army and a small Royal Kampuchea Navy.

Kingdom of Laos (Phra Ratxa A-na-chak Lao):

The Lao Issara (“Free Laos”) movement was an anti-French, non-communist nationalist movement formed by Prince Phetsarath. This movement became the government of Laos after the Japanese coup in Indochina. Shortly after the Japanese pressured the Lao King Sisivang Vong to declare the independence of Laos as a member state of the Co-Prosperity Sphere. Prince Phetsarath himself made an attempt to convince the King to officially unify the country and declare the treaty of the French Protectorate invalid because the French had been unable to protect the Lao from the Japanese forces now rushing into the country. However, King Sisavang Vong said that he intended to have Laos resume its former status as a French colony and was supported by former French Colonial soldiers guerrillas. A month later supporters of Laotian independence announced the dismissal of the king and formed the new government of Laos, the Lao Issara, to fill up the power vacuum of the country. For the next months, the Lao Issara government (United Laos) attempted to exercise its authority by establishing a defense force (Royal Laotian Army) under the command of Phetsarath’s younger half-brother Souphanouvong, with the assistance from the Japanese and Co-Prosperity Sphere forces. With the help of Japanese foreign aid the Lao Issara expended from a small urban-based movement to a national wide movement, and was therefore able to gain mass support from a tribal-oriented population. Its ideas of an independent Laos started to appeal to the masses soon. The Lao Issara also did not manage the finances of the country appropriately independently. The army itself incurred a high cost for its maintenance, and Souphanouvong refused to account for it. Within a very short period of time, the Issara government ran out of money to pay for its own running, let alone anything else. In an attempt to reign in fiscal expenditure and stop inflation, the Minister of Finance Katay Don Sasorith was issued new money from Japan. This made the United Laos Movement and the new state heavily depending on Japanese money. In exchange the government in Vientaine had to accept that Siam/ Thailand the newest member of the Co-Prosperity Sphere would gain some Laotian territory in the provinces of Luang-Prabang, Vientiane and Bassac. In exchange to pay for their support from Japan, the United Laos Movement as the Royal Lao Government allowed the Imperial Japanese Army to grow huge Opium fields so they could be pays for their investment in Laos.

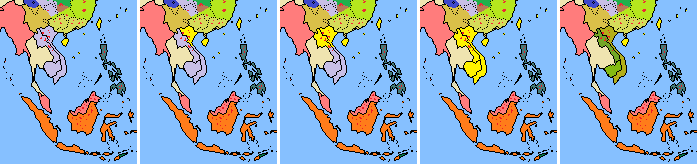

The Japanese occupation of Indochina and the Liberation of these new states as members of the Co-Prosperity Sphere was the last straw for the French and the Americans. The Americans started a full embargo and while Japan and the Co-Prosperity Sphere had gained the Indochinese resources of rice, corn, rubber, coal, pepper, sugar cane, tobacco, hardwood, tin, zinc and phosphates together with the propaganda value to have liberated 24 million Asians from colonial oppression, the situation was problematic and tenser then ever before. Diplomatic relations were tried to be reestablished and Japan hoped the Americans would lift their embargo, or the Dutch Colonies would give them full access to their resources. When the Americans declared they would do so if Japan would leave China and Indochina so that they and the Japanese could accept and respect the internal sovereignty of these countries, the Japanese refused to do so. They had died to archive these gains in China and they knew that their retread from Indochina would mean the return of French Colonial Rule. Unwilling to accept these in American eyes reasonable and mild terms the Japanese only had one way to go if they did not wish to lose their faith; forwards towards war.

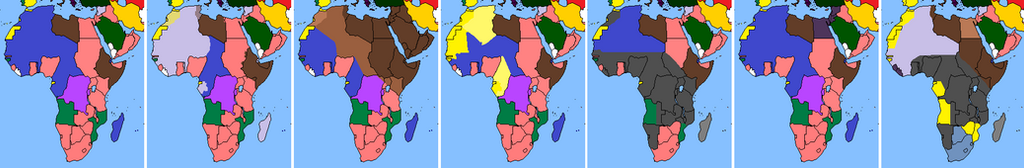

New Map of Southeast Asia: