The General Election of 1953

The New Elizabethans: The General Election of 1953

By the time the Treaty of London was signed, the British economy had staged a dramatic recovery from the damage done by the War. This was staged partly with the help of a housing and infrastructure construction boom (in this way the UK could effectively use People’s Home programmes twice over to recover from two different crises) and also through money made available by the SWF and the Keynes Plan (the latter of which was extended in September 1945 to September 1955). In the decade after 1945, British society became more commercialised and average earnings and standards of living rose steadily, standing at nearly double their nearest European competitor by 1955.

Notable British success stories in this period were in new high tech industries as the manufacturing economy successfully continued to pivot away from heavy industry. In particular, the De Havilland ‘Comet’ became the world’s first commercial jet airliner in 1952 and it fast outpaced its competitors to become the leading aeronautics company in the world by 1960 (although this was no doubt helped by a number of high profile accidents suffered by its American competitor Boeing). Furthermore, the British motor industry remained near-hegemonic in the Commonwealth and dominant in European and South American markets. Of particular note was the firm Rootes Motors Limited, which purchased the entirety of the German Volkswagen company in 1946, proceeding to strip the contents and transport as much of it as they could back to Britain, resulting in the production of the famous ‘Rootes Beetle’ in 1948. Rootes was often bracketed with the brands MG, Rover, Austin, Morris and Jaguar as the ‘Big Six.’ Taken together, the British automobile industry accounted for nearly 52% of the world’s exported cars.

Alongside these successes, the influence of the SWF was could be seen in a number of experimental sectors, although these would not be felt to their fullest extent until further on in the 1950s. As we have already seen, the involvement of the SWF was key to the focus of the British nuclear industry on civilian electrical applications as well as warfare. When giving out SWF funds directly, Keynes set a pattern that would be adopted by his successors: rather than investing in particular companies, the SWF invested in sectors, encouraging competition and stimulating innovation. On the other hand, when money from the SWF was given to the government for investment, they tended to adopt a more statist approach. A good example of the former was the burgeoning British computing industry and a good example of the latter was the British (later Commonwealth) space agency. As we have seen, the CSA was a notable propaganda victory for the Commonwealth and a key factor in Attlee’s decision to go to the country in September 1953, while we shall read more about the computing industry in the future.

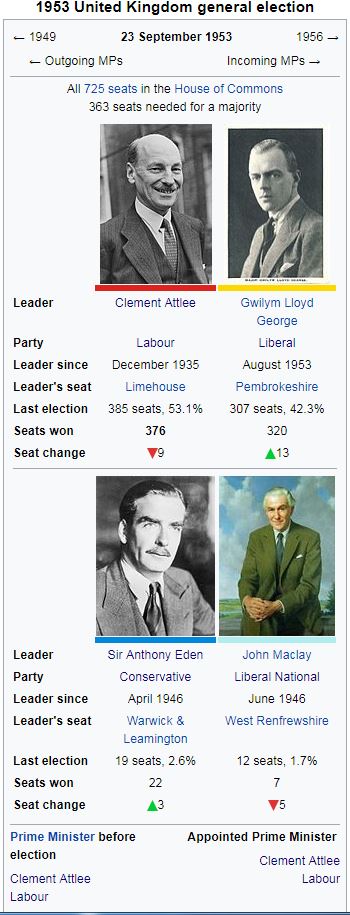

Buoyed by the strong economy, the Megaroc Shock and Churchill’s departure from Parliament, Attlee dissolved Parliament and called an election for September 1953. Despite canny timing and a shrewd campaign, Labour nevertheless suffered the fate of most parties in power and lost seats, although they retained a workable majority of 14. Gwilym Lloyd George had assumed the leadership of the Liberals in the wake of Churchill’s defection and received praise for managing to cobble together a decent enough campaign that saw a net gain of 13 seats, mainly in urban suburbs and the Irish countryside. Five of those seats came at the expense of the Liberal Nationals, who now entered a period of protracted and terminal decline.

The Conservatives, still under the leadership of Anthony Eden, dropped the harder right aspects of their 1949 manifesto and made a gain of three seats. Certainly a success on its own terms, these gains managed to cement the party’s continued existence but it did little more than that. The Conservatives remained as far from relevance as ever. As the Conservative MP Harold Macmillan noted in his diary, when he had first entered politics, a gain of three would have been disastrous and he was apprehensive about the celebrations they caused amongst younger party workers.

By the time the Treaty of London was signed, the British economy had staged a dramatic recovery from the damage done by the War. This was staged partly with the help of a housing and infrastructure construction boom (in this way the UK could effectively use People’s Home programmes twice over to recover from two different crises) and also through money made available by the SWF and the Keynes Plan (the latter of which was extended in September 1945 to September 1955). In the decade after 1945, British society became more commercialised and average earnings and standards of living rose steadily, standing at nearly double their nearest European competitor by 1955.

Notable British success stories in this period were in new high tech industries as the manufacturing economy successfully continued to pivot away from heavy industry. In particular, the De Havilland ‘Comet’ became the world’s first commercial jet airliner in 1952 and it fast outpaced its competitors to become the leading aeronautics company in the world by 1960 (although this was no doubt helped by a number of high profile accidents suffered by its American competitor Boeing). Furthermore, the British motor industry remained near-hegemonic in the Commonwealth and dominant in European and South American markets. Of particular note was the firm Rootes Motors Limited, which purchased the entirety of the German Volkswagen company in 1946, proceeding to strip the contents and transport as much of it as they could back to Britain, resulting in the production of the famous ‘Rootes Beetle’ in 1948. Rootes was often bracketed with the brands MG, Rover, Austin, Morris and Jaguar as the ‘Big Six.’ Taken together, the British automobile industry accounted for nearly 52% of the world’s exported cars.

Alongside these successes, the influence of the SWF was could be seen in a number of experimental sectors, although these would not be felt to their fullest extent until further on in the 1950s. As we have already seen, the involvement of the SWF was key to the focus of the British nuclear industry on civilian electrical applications as well as warfare. When giving out SWF funds directly, Keynes set a pattern that would be adopted by his successors: rather than investing in particular companies, the SWF invested in sectors, encouraging competition and stimulating innovation. On the other hand, when money from the SWF was given to the government for investment, they tended to adopt a more statist approach. A good example of the former was the burgeoning British computing industry and a good example of the latter was the British (later Commonwealth) space agency. As we have seen, the CSA was a notable propaganda victory for the Commonwealth and a key factor in Attlee’s decision to go to the country in September 1953, while we shall read more about the computing industry in the future.

Buoyed by the strong economy, the Megaroc Shock and Churchill’s departure from Parliament, Attlee dissolved Parliament and called an election for September 1953. Despite canny timing and a shrewd campaign, Labour nevertheless suffered the fate of most parties in power and lost seats, although they retained a workable majority of 14. Gwilym Lloyd George had assumed the leadership of the Liberals in the wake of Churchill’s defection and received praise for managing to cobble together a decent enough campaign that saw a net gain of 13 seats, mainly in urban suburbs and the Irish countryside. Five of those seats came at the expense of the Liberal Nationals, who now entered a period of protracted and terminal decline.

The Conservatives, still under the leadership of Anthony Eden, dropped the harder right aspects of their 1949 manifesto and made a gain of three seats. Certainly a success on its own terms, these gains managed to cement the party’s continued existence but it did little more than that. The Conservatives remained as far from relevance as ever. As the Conservative MP Harold Macmillan noted in his diary, when he had first entered politics, a gain of three would have been disastrous and he was apprehensive about the celebrations they caused amongst younger party workers.