Clegg Ministry (2011-2014)

Nick and Olly: The Premiership of Nick Clegg

Nick Clegg talking to 'Daily Mail' political editor Dave Cameron for a profile, November 2011

With most of the Liberal parliamentary party somewhat shell-shocked by the revelations surrounding Leveson, there was far from a crowded field to take the leadership. (Not least, many suspected, because whoever did would also have their heads shot off by the Inquiry.) In the end, Nick Clegg put his hand up. Relatively well known in the public for his work as Education Secretary (2005-08), Environment Secretary (2008-09) and Foreign Secretary (2009-11) and liked amongst his parliamentary colleagues, in many ways he seemed the natural choice. Paul Marshall, from the party’s right, attempted to launch a leadership campaign in response but failed to gain enough nominations from MPs to have his candidature put to the membership. Clegg was thus crowned as leader (and prime minister) without a vote.

In response, Labour, under its new leader Yvette Cooper, immediately tabled a vote of no confidence and the Liberals entered into hurried negotiations with the Conservatives. Although he attracted criticism from his own backbenches for this decision, Letwin agreed to support the government on a confidence and supply basis going forwards. At a special conference of his MPs, Letwin was able to face down his internal opponents and Clegg’s government survived the vote, albeit with a few Conservative rebels.

Clegg got a lot of credit, particularly amongst more liberal newspapers such as the ‘Daily Mail’ and the ‘Herald,’ for holding his nerve and dragging the Liberals through the crisis. For his troubles, his discussions with the Conservatives had produced a substantial policy agenda. Although the Conservatives did not formally join the government, everybody understood the nature of the quid pro quo that Clegg and Letwin had agreed between themselves. Most notably, the Liberals all of a sudden found themselves adopting (or at least partially adopting) a number of policies regarding electoral and campaign finance reform that had been Conservative hobby-horses for many years.

Following the Queen’s Speech in September 2011, the centrepiece of the government’s agenda was the Campaign Finance Bill. In the first place, the bill set up a ‘Register of Lobbyists’ and put in place a raft of measures to put chinese walls between lobbying and MPs. Beefed up regulations were instituted around the Register of Members’ Interests and regulations put in place preventing officials and ministers from meeting with MPs on issues on which the MP in question is paid to lobby. To compensate, MPs were given an above-inflation pay rise. Backbench MPs would now earn £800,000, shadow ministers £1,000,000, ministers £1,400,000 and the Prime Minister £1,800,000 (in all cases plus expenses). In addition, the voting age was lowered to 16. Finally, a limit of £10,000 was placed on individual annual political donations. Initially drafted so as to include cooperatives, companies and the trades unions, this proposal was watered down in committee by Labour MPs who simply would not play ball on this. On the tax front, the government raised the minimum allowance before taxation to £20,000.

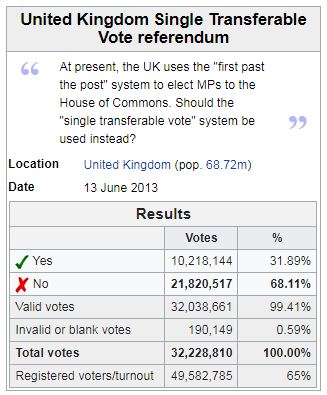

Perhaps the most dramatic proposal, however, regarded voting reform. In 2011, the government set up the Gove Commission on Electoral Reform, chaired by the Conservative Michael Gove and made up of representatives from the three national parties and the four nationalist parties. The report was eventually published in January 2013, suggesting a change to the UK’s electoral system to STV. Following a review of the Gove Report in committee, it was agreed that the proposed change to the electoral system would be put to a public referendum in the summer, ahead of an election some time in either the winter of 2013/14 or the spring of 2014.

The referendum itself was a quietly revolutionary moment in British politics. Referendums had been held in various other Commonwealth countries for a number of reasons - the most politically contentious and famous being the 1975 referendum in Pakistan over the legalisation of civil partnerships - and, during the run of admissions to the Commonwealth in the ‘60s and ‘70s, a referendum in the soon-to-be former-colony became the accepted capstone on that nation’s accession to full membership of the Commonwealth. But there had never been one in the UK itself before, even though they had been proposed many times on any number of topics, from civil partnerships, the single currency and even the expansion of the internet. While constitutional lawyers and judges grumbled about it, most people seem to have been relaxed about the vote’s implications for the future.

From April 2013, Labour shadow ministers, MPs and donors began to come out against the change of electoral systems, providing a united front in contrast to the divided opinions in the Liberals and Conservatives. Labour’s campaign for a ‘No’ vote sought to play on the unpopularity of the Liberals, who, despite a Clegg bounce following his appointment, had lagged firmly behind in the polls since then, with there being particular controversy surrounding the wage rises for MPs. The Labour First Minister of Greater London Ed Miliband described the referendum as an opportunity to punish the Liberals at the polls.

Controversy was aroused, in June, when the No campaign claimed that implementing STV would cost over £200,000,000, a figure which included the cost of holding the referendum in the first place as well as speculative calculations of the cost of voting machines. This injected a degree of rancor into the referendum that would have shocked outside observers who had assumed, at the outset, that this would be a rather sedate affair. In a particularly bizarre incident, Home Secretary Chris Huhne went so far as to threaten legal action against the Shadow Chancellor (and prominent ‘No’ campaigner) Ed Balls for spreading what he called “lies” about the costs of changing the voting system. Elsewhere, much of the public debate centred around questions of the desirability of coalition governments (the British government was divided on this, despite the reasonable performance of the Steel-Mount coalition in the 1990s) and how many safe seats would be removed under the potential new system.

However, the debate failed to electrify the public discourse and was conducted in a fractious atmosphere that was devoid of much serious debate. It was a disappointing moment for Britain’s political reformers, setting back the cause of electoral reform by at least another decade. The referendum also did much to poison the atmosphere between Labour and the other parties in the Parliament, with Labour’s underhand and vicious electioneering causing a great deal of frustration and private anger amongst Liberal and Conservative MPs. There was some loose talk amongst the leadership of the Liberals and the Conservatives that they might try and push electoral reform through Parliament regardless of the referendum but, in reality, the votes just weren’t there to make it work: both parties had notable numbers of MPs who were opposed to reform and both had even more who thought it was mad to so openly reject the verdict of a referendum; and that was without facing up to the problem of trying to pilot it through the Lords, with its in-built Labour majority.

The Liberal minority government continued in place for just under another year, managing the government reasonably well without really accomplishing much. They failed to recover their position in the polls, however, and, despite a reasonably thorough record of domestic reform, few Liberals had any great confidence when Clegg dissolved Parliament and went to the country in July 2014.

Nick Clegg talking to 'Daily Mail' political editor Dave Cameron for a profile, November 2011

With most of the Liberal parliamentary party somewhat shell-shocked by the revelations surrounding Leveson, there was far from a crowded field to take the leadership. (Not least, many suspected, because whoever did would also have their heads shot off by the Inquiry.) In the end, Nick Clegg put his hand up. Relatively well known in the public for his work as Education Secretary (2005-08), Environment Secretary (2008-09) and Foreign Secretary (2009-11) and liked amongst his parliamentary colleagues, in many ways he seemed the natural choice. Paul Marshall, from the party’s right, attempted to launch a leadership campaign in response but failed to gain enough nominations from MPs to have his candidature put to the membership. Clegg was thus crowned as leader (and prime minister) without a vote.

In response, Labour, under its new leader Yvette Cooper, immediately tabled a vote of no confidence and the Liberals entered into hurried negotiations with the Conservatives. Although he attracted criticism from his own backbenches for this decision, Letwin agreed to support the government on a confidence and supply basis going forwards. At a special conference of his MPs, Letwin was able to face down his internal opponents and Clegg’s government survived the vote, albeit with a few Conservative rebels.

Clegg got a lot of credit, particularly amongst more liberal newspapers such as the ‘Daily Mail’ and the ‘Herald,’ for holding his nerve and dragging the Liberals through the crisis. For his troubles, his discussions with the Conservatives had produced a substantial policy agenda. Although the Conservatives did not formally join the government, everybody understood the nature of the quid pro quo that Clegg and Letwin had agreed between themselves. Most notably, the Liberals all of a sudden found themselves adopting (or at least partially adopting) a number of policies regarding electoral and campaign finance reform that had been Conservative hobby-horses for many years.

Following the Queen’s Speech in September 2011, the centrepiece of the government’s agenda was the Campaign Finance Bill. In the first place, the bill set up a ‘Register of Lobbyists’ and put in place a raft of measures to put chinese walls between lobbying and MPs. Beefed up regulations were instituted around the Register of Members’ Interests and regulations put in place preventing officials and ministers from meeting with MPs on issues on which the MP in question is paid to lobby. To compensate, MPs were given an above-inflation pay rise. Backbench MPs would now earn £800,000, shadow ministers £1,000,000, ministers £1,400,000 and the Prime Minister £1,800,000 (in all cases plus expenses). In addition, the voting age was lowered to 16. Finally, a limit of £10,000 was placed on individual annual political donations. Initially drafted so as to include cooperatives, companies and the trades unions, this proposal was watered down in committee by Labour MPs who simply would not play ball on this. On the tax front, the government raised the minimum allowance before taxation to £20,000.

Perhaps the most dramatic proposal, however, regarded voting reform. In 2011, the government set up the Gove Commission on Electoral Reform, chaired by the Conservative Michael Gove and made up of representatives from the three national parties and the four nationalist parties. The report was eventually published in January 2013, suggesting a change to the UK’s electoral system to STV. Following a review of the Gove Report in committee, it was agreed that the proposed change to the electoral system would be put to a public referendum in the summer, ahead of an election some time in either the winter of 2013/14 or the spring of 2014.

The referendum itself was a quietly revolutionary moment in British politics. Referendums had been held in various other Commonwealth countries for a number of reasons - the most politically contentious and famous being the 1975 referendum in Pakistan over the legalisation of civil partnerships - and, during the run of admissions to the Commonwealth in the ‘60s and ‘70s, a referendum in the soon-to-be former-colony became the accepted capstone on that nation’s accession to full membership of the Commonwealth. But there had never been one in the UK itself before, even though they had been proposed many times on any number of topics, from civil partnerships, the single currency and even the expansion of the internet. While constitutional lawyers and judges grumbled about it, most people seem to have been relaxed about the vote’s implications for the future.

From April 2013, Labour shadow ministers, MPs and donors began to come out against the change of electoral systems, providing a united front in contrast to the divided opinions in the Liberals and Conservatives. Labour’s campaign for a ‘No’ vote sought to play on the unpopularity of the Liberals, who, despite a Clegg bounce following his appointment, had lagged firmly behind in the polls since then, with there being particular controversy surrounding the wage rises for MPs. The Labour First Minister of Greater London Ed Miliband described the referendum as an opportunity to punish the Liberals at the polls.

Controversy was aroused, in June, when the No campaign claimed that implementing STV would cost over £200,000,000, a figure which included the cost of holding the referendum in the first place as well as speculative calculations of the cost of voting machines. This injected a degree of rancor into the referendum that would have shocked outside observers who had assumed, at the outset, that this would be a rather sedate affair. In a particularly bizarre incident, Home Secretary Chris Huhne went so far as to threaten legal action against the Shadow Chancellor (and prominent ‘No’ campaigner) Ed Balls for spreading what he called “lies” about the costs of changing the voting system. Elsewhere, much of the public debate centred around questions of the desirability of coalition governments (the British government was divided on this, despite the reasonable performance of the Steel-Mount coalition in the 1990s) and how many safe seats would be removed under the potential new system.

However, the debate failed to electrify the public discourse and was conducted in a fractious atmosphere that was devoid of much serious debate. It was a disappointing moment for Britain’s political reformers, setting back the cause of electoral reform by at least another decade. The referendum also did much to poison the atmosphere between Labour and the other parties in the Parliament, with Labour’s underhand and vicious electioneering causing a great deal of frustration and private anger amongst Liberal and Conservative MPs. There was some loose talk amongst the leadership of the Liberals and the Conservatives that they might try and push electoral reform through Parliament regardless of the referendum but, in reality, the votes just weren’t there to make it work: both parties had notable numbers of MPs who were opposed to reform and both had even more who thought it was mad to so openly reject the verdict of a referendum; and that was without facing up to the problem of trying to pilot it through the Lords, with its in-built Labour majority.

The Liberal minority government continued in place for just under another year, managing the government reasonably well without really accomplishing much. They failed to recover their position in the polls, however, and, despite a reasonably thorough record of domestic reform, few Liberals had any great confidence when Clegg dissolved Parliament and went to the country in July 2014.

Last edited: