Yugoslavia (1945-2000)

The Lion, the Fox and the Eagle: Kingdoms, Republics and Wars in Yugoslavia

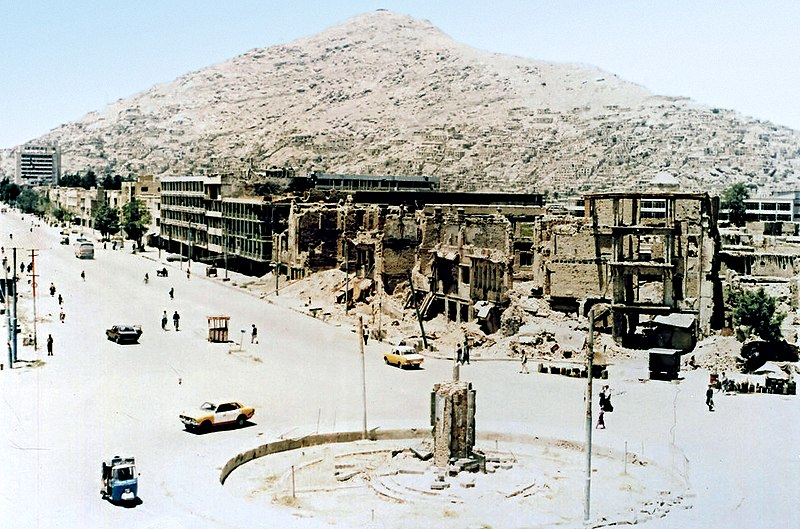

Dubrovnik following its capture by the Army of the Homeland in May 1995

Since the country’s liberation in 1945, Yugoslavia had, along with Austria, come to be nicknamed the ‘crowned republic,’ a reference to the increasingly hegemonic Socialist Party and the country’s economic model, which was based on cooperatives and union-managed corporations. In this context, it also looked like one of Europe’s great success stories, with economic growth into the 1970s which kept pace with Italy (albeit from a lower base) and outpaced that of Spain. However, this covered up a series of ethnic and political disputes that roiled under the surface of Yugoslavian life, which mainly appeared in the form of a conflict between regionalists and centralists. Under the previous conditions of economic growth, however, these political and ethnic divisions could be tamped down.

Yugoslavia had had a privileged position when it came to trade with the countries of the Bucharest Pact and it was particularly badly hit by the events of the Bucharest Mutiny and the concomitant economic crisis that resulted from the Soviets’ forced dissolution of the Bucharest Pact countries and their replacement with a single, protectionist, CIS government. By 1971, it was estimated that over 200 Yugoslavian firms and cooperatives had gone bankrupt, with over 100,000 people laid off, in just two years. Military units stationed in Croat, Albanian and Montenegrin majority regions mutinied and marched on Belgrade. Under pressure, a new constitution, granting increased federal powers to non-Serb ethnic-majority regions, was promulgated in October 1971.

The constitution of 1971 pacified complaints of non-Serbian minorities but it was, in truth, an awkward compromise that everyone recognised as such. During the eleven years of the Federal Kingdom of Yugoslavia (as it was renamed under the ‘71 constitution), the country was beset by constant struggles between centralists (a strange coalition of statist socialists, businessmen and monarchists) and federalists (an equally strange coalition of libertarian socialists, liberals and republicans). This caused severe political instability, resulting in two brief civil wars and nine heads of government during this period. A fresh constitution was promulgated in October 1982, turning the country into a unitary regime and changing its name to the United Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Despite these changes, the United Kingdom fared little better than the Federal Kingdom: there are estimated to have been between six and eight armed rebellions in the year following the death of Aleksandar Rankovic, the first prime minister of the new country, in August 1983. Rankovic had made attempts to mollify federalist sentiment but his death left the country’s government in the hands of nationalist hardliners such as Branko Petranovic and Dobrica Cosic. What pretence there was of democracy in the United Kingdom was finally done away with in 1988, when the ‘82 constitution was amended to remove most of the legislature’s power and centralise decision-making in the person of King Alexander II and his Prime Minister Vasilije Krestic.

This new autocratic regime failed to solve the political contradictions of the Yugoslav state, however, and in 1992 another rebellion broke out in Albania. This one managed to survive the initial forces sent to put it down and, in August 1993, Alexander II issued a decree reinstating the constitution of 1971 and re-forming the Federal Kingdom of Yugoslavia. One of the new government’s first actions was to withdraw from NATO. Nevertheless, by this point there were few who had any confidence in constitutional order anymore and a series of rebellions sprang up in the provinces, collapsing the country into generalised civil war.

With the violence threatening to spill over Yugoslavia’s borders, the Soviets became increasingly concerned and, as such, began to funnel weapons and other supplies to the Serbian nationalist Army of the Homeland headed by Slobodan Milosevic. With the connivance of other security agencies in Italy, Austria and Greece (who, like the Soviets, were concerned about the potential for regional instability), Milosevic’s forces managed to seize control of the country by 1996. They promulgated a new, republican, constitution in November, which renamed the country the ‘Unitary Republic of Yugoslavia’ and which segregated it into different ethnic ‘homelands.’ The Army of the Homeland was condemned internationally for their harsh tactics to move people to their ‘proper’ homelands, which resulted in brutal treatment and the deaths of thousands, especially women and Muslims. During his rule, Milosevic committed massacres against Yugoslavian civilians, denied UN food supplies to starving citizens and conducted a policy of scorched earth, bruning vast areas of fertile land and destroying tens of thousands of homes. NATO mobilised on the Yugoslavian border in December 1995 but eventually stood down due to uncertainty as to what the Soviets’ reaction would be.

Under ethnic Serbian hegemony, Yugoslavia had finally reached a kind of stability, albeit one maintained by the near-permanent repression of non-Serbian minorities. With their far right government, Yugoslavia even became a Mecca for a certain kind of hard right ideologue. The country became home to dozens of right wing and white nationalist training camps, which were semi-authorised by Milosevic’s government. Only France, the Soviet Union and the CIS officially extended recognition to the Unitary Republic and Alexander II and what remaining loyalists he had (of which there weren’t many) continued to be recognised by the UN as the legitimate government of Yugoslavia.

Dubrovnik following its capture by the Army of the Homeland in May 1995

Since the country’s liberation in 1945, Yugoslavia had, along with Austria, come to be nicknamed the ‘crowned republic,’ a reference to the increasingly hegemonic Socialist Party and the country’s economic model, which was based on cooperatives and union-managed corporations. In this context, it also looked like one of Europe’s great success stories, with economic growth into the 1970s which kept pace with Italy (albeit from a lower base) and outpaced that of Spain. However, this covered up a series of ethnic and political disputes that roiled under the surface of Yugoslavian life, which mainly appeared in the form of a conflict between regionalists and centralists. Under the previous conditions of economic growth, however, these political and ethnic divisions could be tamped down.

Yugoslavia had had a privileged position when it came to trade with the countries of the Bucharest Pact and it was particularly badly hit by the events of the Bucharest Mutiny and the concomitant economic crisis that resulted from the Soviets’ forced dissolution of the Bucharest Pact countries and their replacement with a single, protectionist, CIS government. By 1971, it was estimated that over 200 Yugoslavian firms and cooperatives had gone bankrupt, with over 100,000 people laid off, in just two years. Military units stationed in Croat, Albanian and Montenegrin majority regions mutinied and marched on Belgrade. Under pressure, a new constitution, granting increased federal powers to non-Serb ethnic-majority regions, was promulgated in October 1971.

The constitution of 1971 pacified complaints of non-Serbian minorities but it was, in truth, an awkward compromise that everyone recognised as such. During the eleven years of the Federal Kingdom of Yugoslavia (as it was renamed under the ‘71 constitution), the country was beset by constant struggles between centralists (a strange coalition of statist socialists, businessmen and monarchists) and federalists (an equally strange coalition of libertarian socialists, liberals and republicans). This caused severe political instability, resulting in two brief civil wars and nine heads of government during this period. A fresh constitution was promulgated in October 1982, turning the country into a unitary regime and changing its name to the United Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Despite these changes, the United Kingdom fared little better than the Federal Kingdom: there are estimated to have been between six and eight armed rebellions in the year following the death of Aleksandar Rankovic, the first prime minister of the new country, in August 1983. Rankovic had made attempts to mollify federalist sentiment but his death left the country’s government in the hands of nationalist hardliners such as Branko Petranovic and Dobrica Cosic. What pretence there was of democracy in the United Kingdom was finally done away with in 1988, when the ‘82 constitution was amended to remove most of the legislature’s power and centralise decision-making in the person of King Alexander II and his Prime Minister Vasilije Krestic.

This new autocratic regime failed to solve the political contradictions of the Yugoslav state, however, and in 1992 another rebellion broke out in Albania. This one managed to survive the initial forces sent to put it down and, in August 1993, Alexander II issued a decree reinstating the constitution of 1971 and re-forming the Federal Kingdom of Yugoslavia. One of the new government’s first actions was to withdraw from NATO. Nevertheless, by this point there were few who had any confidence in constitutional order anymore and a series of rebellions sprang up in the provinces, collapsing the country into generalised civil war.

With the violence threatening to spill over Yugoslavia’s borders, the Soviets became increasingly concerned and, as such, began to funnel weapons and other supplies to the Serbian nationalist Army of the Homeland headed by Slobodan Milosevic. With the connivance of other security agencies in Italy, Austria and Greece (who, like the Soviets, were concerned about the potential for regional instability), Milosevic’s forces managed to seize control of the country by 1996. They promulgated a new, republican, constitution in November, which renamed the country the ‘Unitary Republic of Yugoslavia’ and which segregated it into different ethnic ‘homelands.’ The Army of the Homeland was condemned internationally for their harsh tactics to move people to their ‘proper’ homelands, which resulted in brutal treatment and the deaths of thousands, especially women and Muslims. During his rule, Milosevic committed massacres against Yugoslavian civilians, denied UN food supplies to starving citizens and conducted a policy of scorched earth, bruning vast areas of fertile land and destroying tens of thousands of homes. NATO mobilised on the Yugoslavian border in December 1995 but eventually stood down due to uncertainty as to what the Soviets’ reaction would be.

Under ethnic Serbian hegemony, Yugoslavia had finally reached a kind of stability, albeit one maintained by the near-permanent repression of non-Serbian minorities. With their far right government, Yugoslavia even became a Mecca for a certain kind of hard right ideologue. The country became home to dozens of right wing and white nationalist training camps, which were semi-authorised by Milosevic’s government. Only France, the Soviet Union and the CIS officially extended recognition to the Unitary Republic and Alexander II and what remaining loyalists he had (of which there weren’t many) continued to be recognised by the UN as the legitimate government of Yugoslavia.