You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Amalingian Empire: The Story of the Gothic-Roman Empire

- Thread starter DanMcCollum

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 89 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 83 Maybe Everything that Dies Someday Comes Back Chapter 84: Echoes of Future Past Interlude #1: The Map Chapter 17 Chapter 18 The Periphery Chapter 85: Of Sickness, Sorrow and Greatness Chapter 86 Heroes Always Get Remembered (Part 1: The Saga of Emperor Theodoric II) Chapter 87 The Bloody Verdict of Metz (The Saga of Emperor Theodoric II, Part 2)Do NOT let this die. I pray you. It's too good to go.

Sorry man! I've been working on the last requirements for my Masters degree. I WILL return to this very soon. I'm just trying to figure out how to best record the Byzantine succession wars

Ah that explains much. Best of luck. What are you getting your masters in?

History, actually. 20th century American, with a focus on the Upper Midwest. All of which I find fascinating, but I just want to be DONE!

History, actually. 20th century American, with a focus on the Upper Midwest. All of which I find fascinating, but I just want to be DONE!

I know how that feels. Godspeed!

So you are studying my neck of the woods, eh?History, actually. 20th century American, with a focus on the Upper Midwest. All of which I find fascinating, but I just want to be DONE!

So you are studying my neck of the woods, eh?

Well, I live in Fargo, so yes. You seem to be across the river. MSUM or Concordia student? You should totally drop me a line!

Check your PM box!Well, I live in Fargo, so yes. You seem to be across the river. MSUM or Concordia student? You should totally drop me a line!

Chapter 11 A Storm of Swords

Chapter 11

A Storm of Swords

The Empire of the East: a History of Rhomania from Constantine I to Justinian IV

Ewan McGowan

[Royal University Press: Carrickfergus, Kingdom of Gaelia, 2010]

…

The first great defeat of Germanus was not militarily, but political. Before declaring his intentions to strip the Purple from Hypatius and restore the dynasty of Justin to power, Germanus had sent letters to his old ally and comrade, Belisarius, who remained in command of the Empire’s forces in Armenia. In these letters, Germanus had pledged to name Belisarius the highest general in the Empire, and to “rely upon his support in all matters.”

Belisarius, for whatever reason, did not respond to his comrade’s call to arms. Although tensions had certainly existed between Justinian I and Belisarius, there had never before emerged any conflict between the two generals of the late-Emperor, and scholars have continued to debate Belisarius’ hesitancy to join his former friend in overthrowing Hypatius. Arguments have tended to emphasize the general’s sense of duty in protecting the Roman frontier with Persia, his own growing antipathy towards the Dynasty of Justin, a sense of loyalty towards the government in Constantinople, as well as salacious rumors that he had been bought off, as it were, by the current Emperor. It seems likely that Belisarius, who had been so badly tarred with the brush of “rebel” for his part in Justinian I’s aborted attempt to regain the throne, simply chose to remain neutral for the time being, to see which way the winds of history would blow. In any case, Germanus, a cautious, if brilliant, general, utterly believed in the support of Belisarius in the events that were to come. He would prove to be bitterly disappointed.

Germanus’ first true threat was the army commanded by Coutez. Although Hypatius had been fearful of executing Germanus, and depriving him of the notable general, he had banished the former Emperor’s cousin to Alexandria, and stationed the loyal Coutez close by, in case the House of Justin should rise in revolt. However, despite Coutez’s loyalty to Constantinople, the same could not be said for his troops, which were largely made up of Syrians. Word quickly spread through the ranks that Germanus was marching to avenge the death of Patriarch Anthimus, in particular, and the Monophytes in particular. When Germanus’ army approached, Coutez’s soldiers began to riot, turning their coats and joining the rebels. The soldiers attempted to capture their general, but he apparently died in the fighting; an act which was to have ramifications for Germanus’ cause, as it pushed Coutez’s brother, Buzes, firmly into the camp of the loyalists in Constantinople.

…

Germanus’ march, throughout the campaign season of 539, was relatively easy, as he marched his army north from Egypt and into Syria, whose governor readily threw his support behind the House of Justin. In September of that year, Germanus pulled off his greatest victory, up to that time, by capturing Antioch after a short siege. He now controlled the entirety of the Empire’s South, and stood ready to strike deep into the heart of the Empire’s Anatolian heartland.

However, Rhomania did not exist within a vacuum. As word spread of the Empire’s civil war, the enemies of Rome were also on the move. To the North, Bulgars began to press into the Balkan peninsula, drawn by the promise of glory and plunder as Hypatius moved troops from the Danube border in order to strengthen the capital and make a move against Germanus. However, the greatest danger lay to the East as the Persians, under their Emperor Khosrau I, mobilized and pressed into Rhomania.

…

The Persian attack came in two waves; the first aimed towards Syria, and the second towards Armenia; the goal was to sweep away any resistance posed by Germanus to the South, while the northern wave struck at Armenia. It was hoped that, by driving out both Germanus and Belisarius, the Roman heartland of Anatolia would be left open, and the Persians would be able to exact concessions from Hypatius; likely including the creation of Armenia as a Persian vassal, and the capture of several key stronghold along the border.

News of the Persian forays did not reach Antioch until May of 540. Germanus, who had set up his administration in the city, was faced with a daunting challenge; either march out of Antioch and meet the Persians, thereby weakening his own position against Hypatius, or lose his entire Southern flank to a foreign foe.

Rather than see Roman territory fall into the hands of Persia, Germanus interrupted his own war for the throne, and marched South. Over the next year, in a series of battles, he was able to check the Persian advance, but not fully disrupt it. Although he remained strong in Antioch, he was unable to prevent the fall of Egypt to the Persians, nor the collapse of much of the defenses of Syria.

Meanwhile, to the North, another tale unfolded. Believing Belisarius to be neutral in the struggle for the crown, the Persians chose to bypass Armenia for the time being, relying, instead, of raiding deep into Anatolia. The forces loyal to Hypatius suffered a series of defeats, further undermining the legitimacy of the Emperor’s claim to the throne.

From 540, through 541, the Empire appeared to be falling apart, due to internal strife and foreign aggression. The Bulgars, seen as savages by the Greeks, sacked Thessaloniki and raided as far south as Athens, spreading fear in their wake. All the while Khosrau continued his advances into Rome, securing control of Egypt and marching into Syria, while pressing forward into Anatolia.

It was at this moment that Belasarius chose to strike. Unwilling, he claimed, to see the Empire of Rome fall into utter chaos, he marched forth from Armenia, cutting off the main northern thrust of the Sassanid army. This maneuver caused the main Persian army, which had long come to see Belisarius as a neutral in the conflict, to retreat back East to deal with their new foe. At the Battle of Manzikert, the Persians were soundly defeated in the North, and fled back to the East.

To the South, Germanus also managed to push back against the Persian threat, although in a much less dramatic fashion. Choosing, momentarily, to turn his attention to the Persian threat, he pushed steadily towards the south, liberating much of Syria and isolating the Persian forces in Egypt. Figuring that the destruction of the main Southern army would free him to pursue his own claims to the throne, he made a treaty with the Vandals to the West, to help support him in his goals of retaking Egypt.

For all of his efforts, however, it would be Belisarius who reaped the greatest sort term reward for his efforts. After staying neutral in the conflict, and only openly engaging in it after a foreign power had entered the fray, Belisarius had won the hearts and minds of a Roman people who had grown dissatisfied with their own Emperor.

In March of 543, Emperor Hypatius, feeling that Belisarius had proved his lately and worthiness, invited the general to Constantinople to be rewarded for his efforts. It would prove to be the greatest mistake of his life.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Okay, I feel like I should explain. I took a bit of time away from this timeline because A) I was finishing my thesis, B) I had gotten myself stuck in a bit of writer's block and C) I wanted to turn my attention towards writing actual fiction.

The problem is, of course, that this timeline always stuck with it; it would gnaw at my mind at weird moments, and I would find myself plotting out the next several decades and centuries. Obviously, I was not meant to abandon it so haphazardly!

At the same time, I didn't want to start a version 2.0 (for those of you from the newsgroup days, you will recognize that this timeline actually IS a version 2.0!). It had a great start and I'd built the foundations of a good narrative. The only thing stopping me was that ... well, I had stopped and allowed myself to be side tracked (also, come to think of it, the title isn't as dazzaling as I'd like. But that's another matter).

And so, here we come to today. I've added a new update, and I hope you all will enjoy it. I can't promise you that I will update this terribly regularly (I do have another TL on the 1900 board, and I'm still dedicated to writing some fiction as well), but I am determined to see this timeline progress. Sorry for the long hiatus, and I hope I haven't lost too many readers in the progress!

Long live the Gothikrike!

A Storm of Swords

The Empire of the East: a History of Rhomania from Constantine I to Justinian IV

Ewan McGowan

[Royal University Press: Carrickfergus, Kingdom of Gaelia, 2010]

…

The first great defeat of Germanus was not militarily, but political. Before declaring his intentions to strip the Purple from Hypatius and restore the dynasty of Justin to power, Germanus had sent letters to his old ally and comrade, Belisarius, who remained in command of the Empire’s forces in Armenia. In these letters, Germanus had pledged to name Belisarius the highest general in the Empire, and to “rely upon his support in all matters.”

Belisarius, for whatever reason, did not respond to his comrade’s call to arms. Although tensions had certainly existed between Justinian I and Belisarius, there had never before emerged any conflict between the two generals of the late-Emperor, and scholars have continued to debate Belisarius’ hesitancy to join his former friend in overthrowing Hypatius. Arguments have tended to emphasize the general’s sense of duty in protecting the Roman frontier with Persia, his own growing antipathy towards the Dynasty of Justin, a sense of loyalty towards the government in Constantinople, as well as salacious rumors that he had been bought off, as it were, by the current Emperor. It seems likely that Belisarius, who had been so badly tarred with the brush of “rebel” for his part in Justinian I’s aborted attempt to regain the throne, simply chose to remain neutral for the time being, to see which way the winds of history would blow. In any case, Germanus, a cautious, if brilliant, general, utterly believed in the support of Belisarius in the events that were to come. He would prove to be bitterly disappointed.

Germanus’ first true threat was the army commanded by Coutez. Although Hypatius had been fearful of executing Germanus, and depriving him of the notable general, he had banished the former Emperor’s cousin to Alexandria, and stationed the loyal Coutez close by, in case the House of Justin should rise in revolt. However, despite Coutez’s loyalty to Constantinople, the same could not be said for his troops, which were largely made up of Syrians. Word quickly spread through the ranks that Germanus was marching to avenge the death of Patriarch Anthimus, in particular, and the Monophytes in particular. When Germanus’ army approached, Coutez’s soldiers began to riot, turning their coats and joining the rebels. The soldiers attempted to capture their general, but he apparently died in the fighting; an act which was to have ramifications for Germanus’ cause, as it pushed Coutez’s brother, Buzes, firmly into the camp of the loyalists in Constantinople.

…

Germanus’ march, throughout the campaign season of 539, was relatively easy, as he marched his army north from Egypt and into Syria, whose governor readily threw his support behind the House of Justin. In September of that year, Germanus pulled off his greatest victory, up to that time, by capturing Antioch after a short siege. He now controlled the entirety of the Empire’s South, and stood ready to strike deep into the heart of the Empire’s Anatolian heartland.

However, Rhomania did not exist within a vacuum. As word spread of the Empire’s civil war, the enemies of Rome were also on the move. To the North, Bulgars began to press into the Balkan peninsula, drawn by the promise of glory and plunder as Hypatius moved troops from the Danube border in order to strengthen the capital and make a move against Germanus. However, the greatest danger lay to the East as the Persians, under their Emperor Khosrau I, mobilized and pressed into Rhomania.

…

The Persian attack came in two waves; the first aimed towards Syria, and the second towards Armenia; the goal was to sweep away any resistance posed by Germanus to the South, while the northern wave struck at Armenia. It was hoped that, by driving out both Germanus and Belisarius, the Roman heartland of Anatolia would be left open, and the Persians would be able to exact concessions from Hypatius; likely including the creation of Armenia as a Persian vassal, and the capture of several key stronghold along the border.

News of the Persian forays did not reach Antioch until May of 540. Germanus, who had set up his administration in the city, was faced with a daunting challenge; either march out of Antioch and meet the Persians, thereby weakening his own position against Hypatius, or lose his entire Southern flank to a foreign foe.

Rather than see Roman territory fall into the hands of Persia, Germanus interrupted his own war for the throne, and marched South. Over the next year, in a series of battles, he was able to check the Persian advance, but not fully disrupt it. Although he remained strong in Antioch, he was unable to prevent the fall of Egypt to the Persians, nor the collapse of much of the defenses of Syria.

Meanwhile, to the North, another tale unfolded. Believing Belisarius to be neutral in the struggle for the crown, the Persians chose to bypass Armenia for the time being, relying, instead, of raiding deep into Anatolia. The forces loyal to Hypatius suffered a series of defeats, further undermining the legitimacy of the Emperor’s claim to the throne.

From 540, through 541, the Empire appeared to be falling apart, due to internal strife and foreign aggression. The Bulgars, seen as savages by the Greeks, sacked Thessaloniki and raided as far south as Athens, spreading fear in their wake. All the while Khosrau continued his advances into Rome, securing control of Egypt and marching into Syria, while pressing forward into Anatolia.

It was at this moment that Belasarius chose to strike. Unwilling, he claimed, to see the Empire of Rome fall into utter chaos, he marched forth from Armenia, cutting off the main northern thrust of the Sassanid army. This maneuver caused the main Persian army, which had long come to see Belisarius as a neutral in the conflict, to retreat back East to deal with their new foe. At the Battle of Manzikert, the Persians were soundly defeated in the North, and fled back to the East.

To the South, Germanus also managed to push back against the Persian threat, although in a much less dramatic fashion. Choosing, momentarily, to turn his attention to the Persian threat, he pushed steadily towards the south, liberating much of Syria and isolating the Persian forces in Egypt. Figuring that the destruction of the main Southern army would free him to pursue his own claims to the throne, he made a treaty with the Vandals to the West, to help support him in his goals of retaking Egypt.

For all of his efforts, however, it would be Belisarius who reaped the greatest sort term reward for his efforts. After staying neutral in the conflict, and only openly engaging in it after a foreign power had entered the fray, Belisarius had won the hearts and minds of a Roman people who had grown dissatisfied with their own Emperor.

In March of 543, Emperor Hypatius, feeling that Belisarius had proved his lately and worthiness, invited the general to Constantinople to be rewarded for his efforts. It would prove to be the greatest mistake of his life.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Okay, I feel like I should explain. I took a bit of time away from this timeline because A) I was finishing my thesis, B) I had gotten myself stuck in a bit of writer's block and C) I wanted to turn my attention towards writing actual fiction.

The problem is, of course, that this timeline always stuck with it; it would gnaw at my mind at weird moments, and I would find myself plotting out the next several decades and centuries. Obviously, I was not meant to abandon it so haphazardly!

At the same time, I didn't want to start a version 2.0 (for those of you from the newsgroup days, you will recognize that this timeline actually IS a version 2.0!). It had a great start and I'd built the foundations of a good narrative. The only thing stopping me was that ... well, I had stopped and allowed myself to be side tracked (also, come to think of it, the title isn't as dazzaling as I'd like. But that's another matter).

And so, here we come to today. I've added a new update, and I hope you all will enjoy it. I can't promise you that I will update this terribly regularly (I do have another TL on the 1900 board, and I'm still dedicated to writing some fiction as well), but I am determined to see this timeline progress. Sorry for the long hiatus, and I hope I haven't lost too many readers in the progress!

Long live the Gothikrike!

Wouldn't the Gothic for a realm be reik? I think rike is North Germanic.

http://archive.org/stream/deutschgotisches00prieuoft#page/n71/mode/2up

Yes, reiki. Or thiudanassus, thiudangardi when your focus is on the kingship.

http://archive.org/stream/deutschgotisches00prieuoft#page/n71/mode/2up

Yes, reiki. Or thiudanassus, thiudangardi when your focus is on the kingship.

Chapter 12: The Soldier King

Chapter 12

The Soldier King

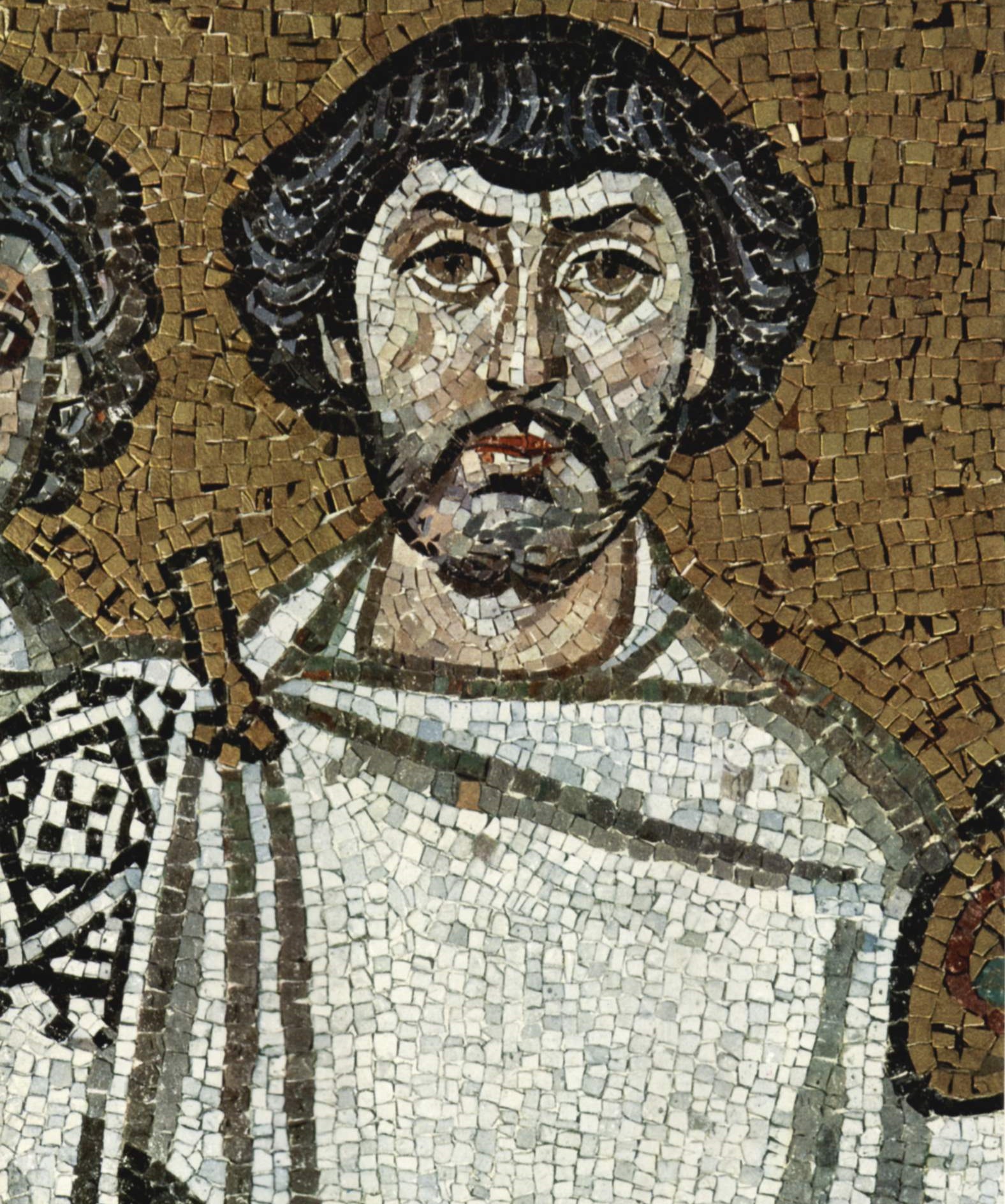

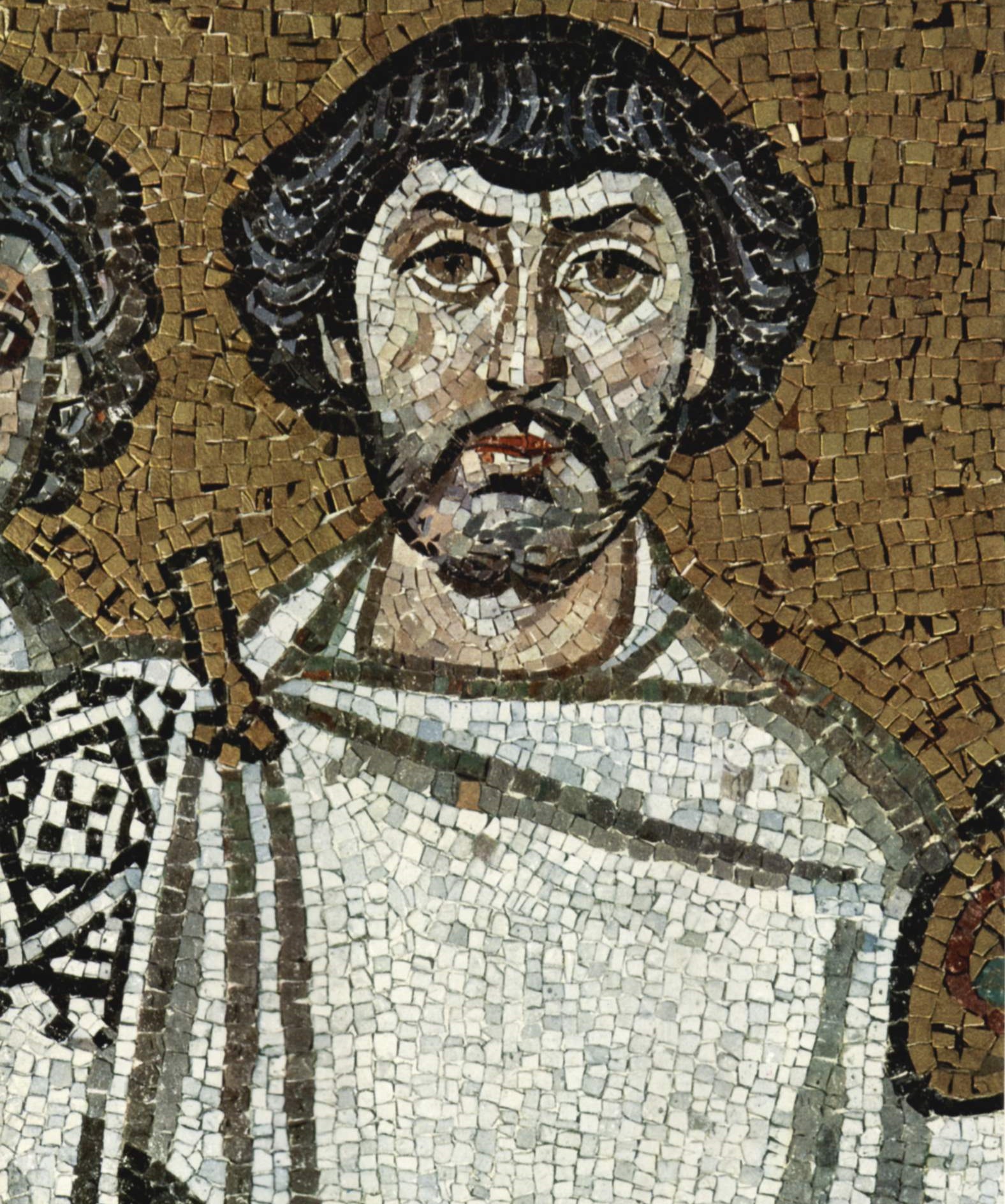

“Belisarius has gone down as one of the greatest folk heroes of the Rhomanio. Seen as a brilliant military leader, a devout patriot, and simple soldier, he had also attracted stories which paint him as a true friend of the ‘every man.’ To many a young Rhoman, to even this very day, he is held up as a shining ideal for which to strive. All of which, of course, makes his tragic downfall all the more poignant.” – Gregory Miller, Belisarius, a Life

The Empire of the East: a History of Rhomania from Constantine I to Justinian IV

Ewan McGowan

[Royal University Press: Carrickfergus, Kingdom of Gaelia, 2010]

…

Belisarius’ arrival to Constantinople in May of 543 set off a period of wild celebration in the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The General’s stinging defeats of the Persians over the past year had excited the imaginations of a population which had grown weary of war, and the anxiety which Germanus’ rebellion, and the Persian invasion, had caused.

Belisarius’ entrance into the city sparked off near riots as the citizenry of the capital surged towards the military parade to capture only a glimpse of the conquering hero. The fact that the General had not uet won the war, mattered little to the populace; he had dealt the Persians a series of defeats and delivered to the Rhomans the one thing which had been sorely lacking in the years since the fall of Justinian: hope.

The Emperor himself had lent a hand in creating the popular fervor, openly declaring that Belisarius was a new Cincinnatus, who would deliver the Romans from their darkest hour. Although hamstrung by his powerful Patrician allies, Hypatius still possessed a certain flair for the dramatic; and it was in full view for Belisarius’ arrival. First, was the formal military procession as the General entered the capital, and then the great parade which was thrown in his honor (such parades had often been the staple of Roman conquests in the past. The fact that Belisarius had yet to conquer anything was considered a moot point). Finally, the festivities were capstoned with a series of chariot races at the rebuilt Hippodrome; perhaps as an attempt to remind the populace that it had been a series of races, years earlier, which had raised Hypatius to the throne as the people’s Emperor. [FN1]

One need not have read Skulson to understand the beleaguered Emperor’s goals. Although having come to power in the Nika Riots, as a representative of the citizens of Constantinople, Hypatius’ power stemmed largely from the rich landed families who have worked to secure his position in the first place. As such, even before the outbreak of the Civil War and invasion, he had come to be seen as an ineffectual leader, who was unable to put enough pressure upon the Rhoman elites to even finance the rebuilding of the capital city. The Civil War had made things even worse, as news reached the capital of Germanus’ string of early victories. Then, of course, had come the Persian invasion, and Hypatius’ armies had been largely ineffectual. Had it not been the Persians, Germanus might have been able to march upon the capital by now, rather than being harassed and harried in the south; and had it not been for Belisarius, the Persians might well have reached the city walls. As such, it was of the up most necessity for Hypatius to shore up his support by associating himself closely with Belisarius.

The problem was, of course, that Belisarius was not a strong supporter of Hypatius. Having risen to initial prominence under Justianian I, for his creation of a unit of heavy calvary/archers, he had taken part in the deposed Emperor’s attempt to retake the throne. Afterwards, he had humbly taken Hypatius’ pardon, and gratefully taken his assigned post in Armenia. Belisarius’ main loyalty was to the Roman State, and not to an individual Emperor; he was thankful for Hypatius’ pardon and his continued ability to serve the Empire, but was not personally loyal to Hypatius himself. In fact, it had not been the Civil War which had first roused Belisarius from his slumber, it had been the invasion of the Empire by Persia. From that point onward, he had fought as a representative of the Roman Empire, and not of a single Roman Emperor. [FN2]

So, the question remains, why did Belisarius allow himself to become associated with Hypatius’ faction? It would seem that he carefully weighed the options, and thought that Hypatius had a better chance to retain his throne than did Germanus, and that a strong ruler was needed to push back against the Persian forces.

A History of Time of Troubles

By: Procopius

Trns: Matthias M. Schaible

[London: University of London Publishing, 2006]

…

It came to pass that Belisarius’ arrival in the capital unleashed the passions of the people, both rich and poor. For years Hypatius had held the throne, and for years it seemed as if God had punished all of Rome. He was a weak ruler, and possibly demon sent. Stories abound of his lethargy and wickedness. It is said that he once allowed a child to burn to death, after falling into a fire, because he was too busy to rush to the child’s help. [FN3]

Now, many felt that Hypatius was weak, and would be unable to save the Empire in its time of need. Even those who had once supported the Emperor were now turning away from him. They came to Belisarius and offered him the crown. However he had seen what these same men had done to Hypatius, elevating him to the throne and now turning their back on him. Still, being an ambitious man, he set them a challenge: “We shall see who the people prefer,” he stated, “Hypatius or myself. I shall abide by their decision.” [FN4]

The next day, riots began after the chariot matches had been completed. The crowd cried out for Belisarius, to save them from their enemies. When soldiers were sent in to quell the mob, they instead joined them, and a great mob began to form in front of the Imperial palace. Hypatius did not know what to do; much like Justinian before him, he went out to meet the crowd; but they continued to call for Belisarius. Finally, members of Hypatius’ own guard betrayed him; they captured him and delivered him to the General.

Now Belisarius knew who the people wished to lead them. He met the crowd and accepted their calls, and agreed to become their Emperor. However, he showed pity to Hypatius; he ordered the former Emperor should be sent into exile and that his ears should be removed “So that a crown cannot fit upon his head any longer.”

And so, it was that Belisarius came to be crowned Emperor of Rome and tasked with driving out the Persians and destroying the rebels in the land.

The Empire of the East: a History of Rhomania from Constantine I to Justinian IV

Ewan McGowan

[Royal University Press: Carrickfergus, Kingdom of Gaelia, 2010]

…

Having secured the throne, Belisarius, ever the military man, moved to quell the threats to the Empire. Giving himself time to reinforce his own army, he struck directly at the Persians, who continued to be a presence in Anatolia. In the Battle of Caesarea, Belisarius personally led his army and destroyed the invading Persian force in 544. This defeat was enough to send Khosrau I to the bargaining table. Although the Persians still held land in Syria and Egypt, they had been greatly weakened by the efforts of Germanus. No longer feeling it was possible to take control of Armenia, as had originally been planned, the Persian Shah agreed to a reconstituting of the Rhoman/Persian border, and a small annual payment in exchange for an “Eternal Peace” before the two Empires [FN5]

Now the problem which faced Belisarius, was to turn his attention towards the Balkans, and push back the Avars who had sacked Athens, or to march directly upon Antioch and end Germanus’ rebellion. Eventually, it was decided to seek a truce with the Avars, which would, at least, hold them at bay while he strengthened his power within the realm. In April of 545, Belisarius marched upon Antioch, seeking to put an end to the rebellion, once and for all.

Germanus was a greatly weakened figure by this point; while Belisarius had gained the glory in fighting the Persians to the North, it had been Germanus who had blunted the edge of their southern spear. For two years he had managed to sustain his position in Antioch, while marching through Syria and conducting a guerilla campaign against the Persians. Although his efforts had gained him support in both Syria and Egypt, it had left his forces bloodied and exhausted; he simply did not have the strength to meet Belisarius in open battle.

In May of 545, a representative of Germanus’ army, still stationed in Antioch, met with Emperor Belisarius and offered him a deal; Germanus who immediately leave for exile, as long as the city of Antioch would suffer not harassment, and his soldiers would all be given pardon. The Emperor, who did not wish to see his forces, weakened as they were against the Persians, and who still looked forward to a long campaign against the Avars, quickly agreed. Days later, Antioch was handed over the Belisarius, and Germanus slipped away into exile. He would, of course, return.

[FN1] There really isn’t a lot of information about the real Hypatius in OTL, and that which does exist, paints him as almost an archetypical Roman Patrician, and a weak one at that. In this case, I figured, whether he had a flamboyant bone in his body, or not, this would be the perfect chance for him to strengthen his own rule. If he wouldn’t think of it himself, he likely had some advisor who would. Of course, in this case, it turned out to be the exactly wrong thing to do, but, hey, can’t win them all!

[FN2] From me own reading, this does not seem to fall entirely outside of Belisarius’ personality. However, I would admit, I have been largely influenced by L. Sprauge D’Camp’s portrayal of him, which I read in High School, so long ago.

[FN3] In OTL, Procopius claimed that Justinian was possessed by Demons, which caused his head to occasionally disappear, much to the horror of visiting dignitaries. I doubt that a claim like this would be too far out of the realm of possibilities.

[FN4] Procopius’ depiction of Belisarius is rather … nuanced, due to the political realities of the time under which he is writing.

[FN5] As I mention later on in the update, the unsung hero of this campaign in Germanus who is able to hold the Persians at bay, harassing them in the South, and weakening their position enough that, following the Battle of Caesarea, they agree to throw in the towel. Not, of course, that Germanus is getting any credit for this at the time.

Okay. So, once again, thanks for all of the support here guys. I'm not sure how many times a TL gets revieved after a year, but I'm going to do my best to do just that!

Now, this should bring the Byzantine section of the TL to a momentary conclusion (although it will soon merge into the main Gothic story line). I plan to turn back to the Goths and show the development of their state following the conclusion of the war against the Franks.

So, I need to ask (especially as I took such a long break), does anyone have any questions going forward? Also, does anyone want to see what's going on in a specific part of the world? Although butterflies abound, I'm not sure how much things would have changed outside of the Mediteranian world as of yet; but I do plan on turning my attention towards Great Britain and Germany eventually; and we've got so many steppe nomans starting to flood in ... who knows WHAT could happen!

Wouldn't the Gothic for a realm be reik? I think rike is North Germanic.

http://archive.org/stream/deutschgotisches00prieuoft#page/n71/mode/2up

Yes, reiki. Or thiudanassus, thiudangardi when your focus is on the kingship.

Bah; show off!

Now, I have to admit, I'm no linguist, but ... yeah, I'm going to have to check that site out!

So, I give you guys one of the board favorite could-have-been-Emperors, a ton of good foreshadowing, and nada?

Chapter 13: Don’t Fear the Reaper

Chapter 13

Don’t Fear the Reaper

“Winning the war is easy. Its winning the peace that is hard.” – Emperor Belisarius I of Rhomania

The Empire of the East: a History of Rhomania from Constantine I to Justinian IV

Ewan McGowan

[Royal University Press: Carrickfergus, Kingdom of Gaelia, 2010]

Belisarius had no sooner returned to the capital, than he turned his attention towards matters to the West. All the while the Empire’s attention had been focused internally, and on the East, the forces of the Avars had made steady incursions deep into the Balkan Peninsula; reaching as far south as Athens. Having settled matters with the Persians, and accepting the surrender and exile of Germanus, the new Emperor felt himself ready to deal with his last remaining foes.

Belisarius, of all possible commanders was the one man who was best fit to lead an incursion against the Avars. Prior to the fall of Justinian I, and the resulting waves of social unrest and civil war, Belisarius had begun his rise to prominence by convincing the then-Emperor of the need to create a new dynamic fighting force, the Bucellarii, which would combine the strengths of two of Rome’s greatest foes; the Huns and the Goths. The Bucellarii would act as the heart of every army Belisarius would create during the length of his career, and would go on to become one of the most renowned fighting forces in the history of Europe. [FN1]

Belisarius was confident that his forces would be able to sweep away the Avars and drive them back across the Danube. Partially, he was confident of the strength of his own forces, but, more so, he was sure that the Avars had allowed themselves to become ensnared in a tactical mire. Following the sacking of Athens, the Avar Khan had realized the danger of attempting to hold the city; the mountainous terrain of the region made it difficult of his army to maneuver and the presence of a Rhomanian force in Corinth to the West. As such, he had pulled his forces back North to Thessalonica, which had fallen the year earlier and where he had set up his temporary capital.

This move, however, left the Avars vulnerable to a counter attack by the Rhomanians. Belisarius’s plan was to land a small Army to the Southwest of Thessalonica where it would meet up with those forces which had previously been stationed in Corinth. At the same time, the full strength of the Rhoman fleet would sail into the bay and harass the city directly, while the Emperor’s main force would march in from the East. It was hoped that the Avars, unused to sieges, would abandon the city and move North, where they would be attacked on both sides by the Rhoman forces.

…

Belisarius’ plan was pulled off with great success; the Avars, faced with the Rhoman navy and a popular uprising in the Thessaloniki, abandoned the city and rode North, hoping to find a better environment to give battle. Outside the village of Evropos, to the north of the city, they were fallen upon by Belisarius’ imperial army and those forces which had moved in from the southwest. In the ensuing battle, the Emperor’s Bucellarii were able to harry the Avars and then charged them with lances and swords, scattering their enemies. The Avars were soundly beaten and the Khan was forced to limp back north, after securing safe passage from the Rhomans, and agreeing to pay an annual tribute. Belisarius had won another great victory for the Empire, but the true horror was waiting for him in Constantinople. [FN2]

The Norræna Fræðibók [FN3]

Entry: The Plague of Belisarius

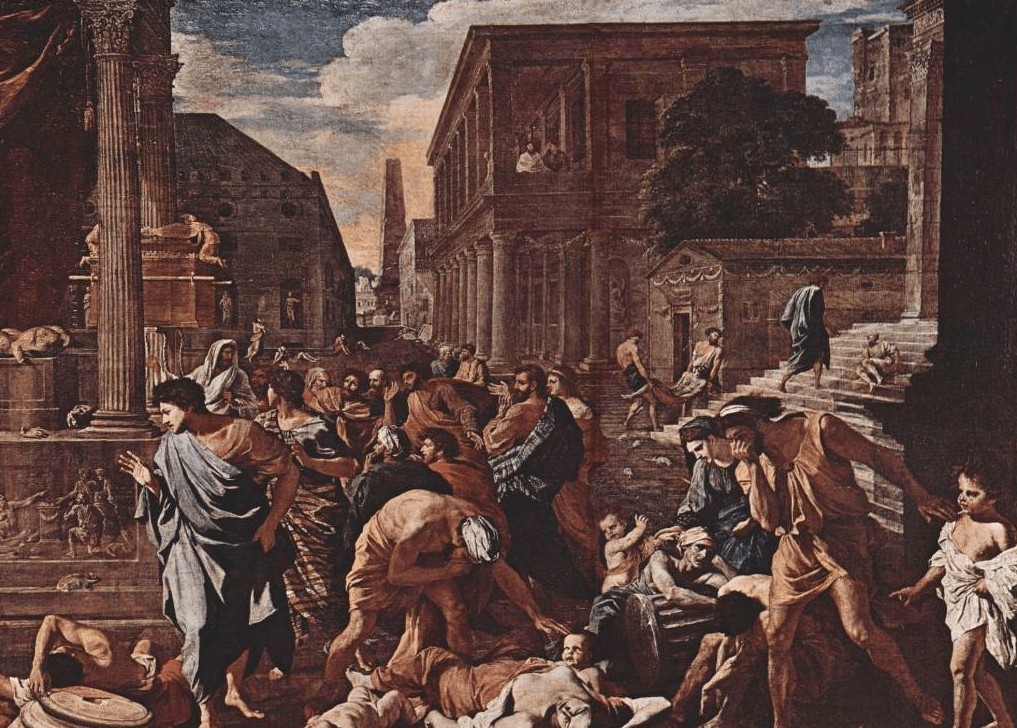

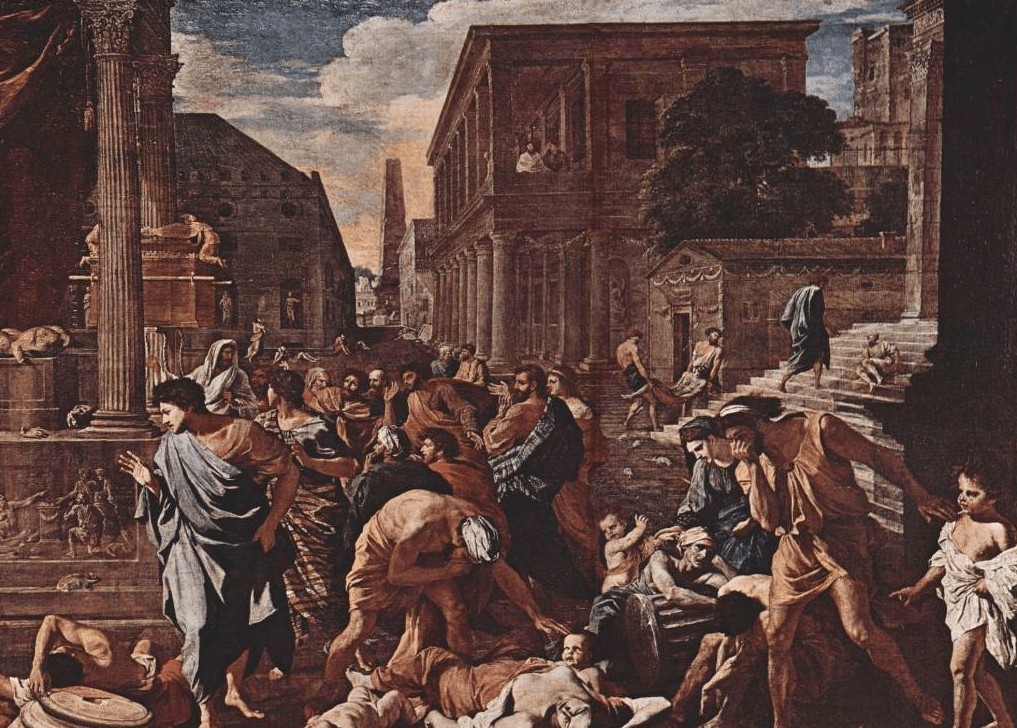

The Plague of Belisarius (545-46) was an epidemic which affected the Eastern Roman Empire (Rhomania), including its capital of Constantinople, and much of Europe from the years 545-546. It is remembered as one of the greatest plagues in human history, rivaling the Great Death of the 13th Century. Estimates of the death total range from between 20 and 25 million people worldwide during the initial contagion, and waves of the plague would return to strike the Mediterranean basin until the 8th Century. Modern historians have named the plague after Belisarius, as it was during the first years of his reign that it first reached the Western world. [FN4]

The outbreak of the Plague in Constantinople is thought to have been carried by rats who had were carried to the city within grain ships headed from Egypt. Constantinople, being then one of the largest cities in the world, was entirely dependent upon grain shipments to feed its population. Procopius, the famed Rhomanian historian, writes of the first cases of the plague in Suez Egypt in 544. By his own estimates, at the height of the plague, over 10,000 people a day were dying within the Empire’s capital, although modern historians have questioned the veracity of those numbers.

The effects of the plague within the Empire were far reaching. Having just emerged from a five year period of civil war and invasion, the Empire was already struggling. Belisarius, upon receiving the first word of plague, immediately ordered the capital under quarantine, but this did little good as the sickness was soon reported in every major port within the Empire, including Antioch and Thessaloniki. Over the course of the next year, the plague by some estimates was to kill nearly 40 percent of the population of Constantinople:

“There was no room to house the dead. Great piles of bodies were built upon the streets and burned. Few priests could be found to give sympathy to the dying, and those who did were soon dead themselves. The pestilence swept through the farming communities, leaving them empty. Both city dweller and farmers died alike. The Emperor was weakened by misery, and turned to his wife for support, as he knew he could do nothing to end the suffering” – Procopius. [FN5]

In February of 546 the plague struck close to the Imperial family, as Belisarius’s daughter Joannina fell sick and died of the illness. Belisarius was to have a church built for his beloved eldest daughter and, upon the chapel’s completion, would have her reburied within its walls. [FN6]

As the plague ravaged Rhomania, further weakening the Empire’s strength, it also began to move West, reaching Rome and Ravenna in September of 545 and Massalia and other major ports shortly thereafter. Much as it had in the East, the plague found a land which have been ravaged by years of war. From there it is thought to have reached as far away as Gaelia and Scandinavia. Although the estimated total number of dead in the West did not reach the same levels as in the East, this is because the population of the West was already substantially lower than that of the Eastern Empire.

It is believed that the Plague of Belisarius was the earliest outbreak out the Bubonic Plague.

The Glory of Emaneric’s Heirs: the Lectures of Dr. Valamir Fralet

Trans. Edwin Smith

Bern [OTL: Verona, Italy]: Skipmann and Sons Publishing, 1997

…

Theodemir had only just returned to Ravenna, following the conclusion of his campaign in Gaul, when news of the Plague first reached him. The first response by the King was remarkably similar to that of his Eastern counterpart, Belisarius, in that he quickly sealed the gates of the city and attempted to impose a rude form of quarantine, which he quickly abandoned when it became obvious that his efforts were for utterly ineffectual. The King’s second response, however, shines a bright light upon his character; he quickly ordered his two remaining sons out of the capital, sending them to a stronghold in the Alps, along with his wife. Having already lost one heir, he was unwilling to put his family in any more danger.

Rather than flee the capital himself, however, he declared his intention to stay and offer a steady hand to the citizens of the realm. Daily, it is recorded, mainly by Wulfila Strabo, of course, but others as well, Theodemir organized the relief effort, continuing to run the government as best he could, and making public appearances to maintain the people’s faith in him. This is likely what is remembered in the old folk story, of the King challenging Death to a duel for the lives of his countrymen. A less fantastic tale, albeit one that reveals a great deal of Theodemir’s character, was his public berating of a group of priests who refused to administer to the dying, for fear of losing their own lives. We also have evidence that the King petitioned the Arian Bishop of Ravenna, Fadar John, to give more support to the downtrodden and dying.

For months the plague raged and both Ravenna and Rome are said to have lost nearly 30 percent of their population. The effects were similar throughout Italy and Gothia, with Hispania likely suffering less than the other provinces. However, one of the most dramatic examples of the Plagues desolation was in northern Gaul. Having already suffered the full weight of Theodemir’s revenge against the Meroving Franks, the land now found itself being cleansed by the great sickness. Paris, once the capital of the Frankish kingdom had already been burnt by Theodemir, along with much of the countryside; now it was the plague’s turn to kill off the survivors of the war. Many survivors in Gaul blamed Theodemir for the plague, and believed it was a further step in his vengeance against the Franks and their Gaulish allies. The destruction was so great, that the modern name for the region Authia, stems from the ancient Gothic word Authida, which means ‘wasteland’. [FN7]

Meanwhile, in Britain, the plague appears to have caused renewed fighting between the Britons and the Saxon invaders, after years of stalemate. No one is quite sure why, or even if, the Britons were more greatly affected by the plague than their Germanic counterparts but, whatever the case, the Saxons were soon pressing deeper into Briton territory. [FN8]

The effects of Belisarius’ Plague upon the West were as great as those caused by the Great Death centuries later. The plague had struck a land already depopulated by years of war and a declining economy. To the North, much of Northern Gaul lay utterly in ruins and was depopulated. Although Hispania had emerged relatively unscathed, at least in comparison to the rest of the realm, the economy of the region had still been greatly affected, and there were rumors of renewed Suebian efforts to expand their territory into the rest of the peninsula. Gothia had been first harder, especially such cities as Ravenna and Masalia. However, it was to be the Romans of Italy, and the Kingdom’s urban centers, which would be struck the hardest by the Plague … [FN9]

[FN1] The Bucellarii in OTL are pretty much what is described here. I figure that this versatile force ends up becoming on the mainstays of the Rhomanian military and, as a result, coupled with the eventual romantic portrayal of Belisarius which emerges, they go one to be seen in a similar light to the Knights of OTL Europe. Of course, the Eastern Empire is hardly Feudal, and so the analogy only goes so far …

[FN2] I am not going to lie; I have very little background in military history, which is one of the reasons why my accounts of military encounters in this TL have been so vague. After looking at some maps of around Thessaloniki, Evropos appeared to be a good place for the armies to meet up. If anyone can suggest another place, or a more reasonable series of events, I am all ears!

[FN3] This is my attempt to try to reconstruct what a native Nordic phrase might be for “Norse Encyclopedia” (much like the Encyclopedia Britannica). Sadly, I don’t speak Old Norse (or even Icelandic), and so I went with an Icelandic translation of the phrase “Norse Lore Book”. Does it work? I don’t know! I’m certainly no linguist. But, hey, A for effort, right?

[FN4] The Plague of Justinian in OTL was largely as devastating as I’m describing it here. I’m of two minds over whether it would be better or worse in this ATL. On one hand, the Plague struck just as the height of the Gothic Wars, which had decimated Italy, giving a firm group for illness to spread. However, in the ATL, trade in the Mediterranean is going stronger than in OTL do to more stable trade networks, so it is likely spread faster and to different places. My eventual conclusion was that these factors would likely cancel one another out and leave us with a Plague that is pretty much as bad as in OTL (albeit, maybe, a bit more widespread, although there is some evidence of it hitting Ireland in OTL as well).

[FN5} Procopius in OTL and in this ATL views Belisarius as a bit of a weak willed buffoon, controlled by his evil, cheating, wife. As Belisarius is Emperor in the ATL, he had hushed up his feelings somewhat; but, as anyone who knows about the Secret Histories can tell you … somewhat wasn’t a lot for this guy. Oddly enough, Belisarius’ reputation continues to be strong to the present day in the ATL, which means Procopius, although still considered a good source for the time, is judged even harder than in OTL.

[FN6] In OTL, Belisarius had only one daughter with his wife. In the ATL he manages to have two. This is, of course, not that same daughter as OTL, as she was born after the POD, but simply shares a name with her OTL counterpart.

[FN7] This is my, likely silly, attempt to reconstruct a Gothic phrase and how it might be bastardized over time.

[FN8] In OTL, fighting between the Anglo-Saxons and British picked up right about this time as well, leading some to speculate that the Plague had have had a hand in doing this. In the ATL, the same thing occurs. My attitude is that the butterflies have yet to terribly impact what’s going on in Britain. They are having an impact, of course, and the same people being born in OTL and not going to show up in the ATL. But the broad trends are still roughly the same … for now.

[FN9] It just makes sense that the more ‘urban’ Roman populations would get hit harder than the more rural Gothic population at this point. Italy has certainly not been denuded of life (and is in much better shape than OTL at this same point), but the Romans definitely get hit moderately worse than their Gothic co-nationals. I suspect this will have a noticeable impact on how things develop.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

So, I lied. I had promised to look at the structure of the Gothic state during this update, but realized that I really needed to explain the Plague and its impact upon both the East and the West before I could really move forward with the narrative, after all. I hope you all forgive me!

In any case, after a year long hiatus, I just produced three chapters in about a week! Not too bad, if I do say so myself.

As always, comments, questions, random thoughts are always welcome! Feel free to fix my horrible attempts to butcher other languages or correct any details you feel just don't fit. I don't care; I just want comments!

Don’t Fear the Reaper

“Winning the war is easy. Its winning the peace that is hard.” – Emperor Belisarius I of Rhomania

The Empire of the East: a History of Rhomania from Constantine I to Justinian IV

Ewan McGowan

[Royal University Press: Carrickfergus, Kingdom of Gaelia, 2010]

Belisarius had no sooner returned to the capital, than he turned his attention towards matters to the West. All the while the Empire’s attention had been focused internally, and on the East, the forces of the Avars had made steady incursions deep into the Balkan Peninsula; reaching as far south as Athens. Having settled matters with the Persians, and accepting the surrender and exile of Germanus, the new Emperor felt himself ready to deal with his last remaining foes.

Belisarius, of all possible commanders was the one man who was best fit to lead an incursion against the Avars. Prior to the fall of Justinian I, and the resulting waves of social unrest and civil war, Belisarius had begun his rise to prominence by convincing the then-Emperor of the need to create a new dynamic fighting force, the Bucellarii, which would combine the strengths of two of Rome’s greatest foes; the Huns and the Goths. The Bucellarii would act as the heart of every army Belisarius would create during the length of his career, and would go on to become one of the most renowned fighting forces in the history of Europe. [FN1]

Belisarius was confident that his forces would be able to sweep away the Avars and drive them back across the Danube. Partially, he was confident of the strength of his own forces, but, more so, he was sure that the Avars had allowed themselves to become ensnared in a tactical mire. Following the sacking of Athens, the Avar Khan had realized the danger of attempting to hold the city; the mountainous terrain of the region made it difficult of his army to maneuver and the presence of a Rhomanian force in Corinth to the West. As such, he had pulled his forces back North to Thessalonica, which had fallen the year earlier and where he had set up his temporary capital.

This move, however, left the Avars vulnerable to a counter attack by the Rhomanians. Belisarius’s plan was to land a small Army to the Southwest of Thessalonica where it would meet up with those forces which had previously been stationed in Corinth. At the same time, the full strength of the Rhoman fleet would sail into the bay and harass the city directly, while the Emperor’s main force would march in from the East. It was hoped that the Avars, unused to sieges, would abandon the city and move North, where they would be attacked on both sides by the Rhoman forces.

…

Belisarius’ plan was pulled off with great success; the Avars, faced with the Rhoman navy and a popular uprising in the Thessaloniki, abandoned the city and rode North, hoping to find a better environment to give battle. Outside the village of Evropos, to the north of the city, they were fallen upon by Belisarius’ imperial army and those forces which had moved in from the southwest. In the ensuing battle, the Emperor’s Bucellarii were able to harry the Avars and then charged them with lances and swords, scattering their enemies. The Avars were soundly beaten and the Khan was forced to limp back north, after securing safe passage from the Rhomans, and agreeing to pay an annual tribute. Belisarius had won another great victory for the Empire, but the true horror was waiting for him in Constantinople. [FN2]

The Norræna Fræðibók [FN3]

Entry: The Plague of Belisarius

The Plague of Belisarius (545-46) was an epidemic which affected the Eastern Roman Empire (Rhomania), including its capital of Constantinople, and much of Europe from the years 545-546. It is remembered as one of the greatest plagues in human history, rivaling the Great Death of the 13th Century. Estimates of the death total range from between 20 and 25 million people worldwide during the initial contagion, and waves of the plague would return to strike the Mediterranean basin until the 8th Century. Modern historians have named the plague after Belisarius, as it was during the first years of his reign that it first reached the Western world. [FN4]

The outbreak of the Plague in Constantinople is thought to have been carried by rats who had were carried to the city within grain ships headed from Egypt. Constantinople, being then one of the largest cities in the world, was entirely dependent upon grain shipments to feed its population. Procopius, the famed Rhomanian historian, writes of the first cases of the plague in Suez Egypt in 544. By his own estimates, at the height of the plague, over 10,000 people a day were dying within the Empire’s capital, although modern historians have questioned the veracity of those numbers.

The effects of the plague within the Empire were far reaching. Having just emerged from a five year period of civil war and invasion, the Empire was already struggling. Belisarius, upon receiving the first word of plague, immediately ordered the capital under quarantine, but this did little good as the sickness was soon reported in every major port within the Empire, including Antioch and Thessaloniki. Over the course of the next year, the plague by some estimates was to kill nearly 40 percent of the population of Constantinople:

“There was no room to house the dead. Great piles of bodies were built upon the streets and burned. Few priests could be found to give sympathy to the dying, and those who did were soon dead themselves. The pestilence swept through the farming communities, leaving them empty. Both city dweller and farmers died alike. The Emperor was weakened by misery, and turned to his wife for support, as he knew he could do nothing to end the suffering” – Procopius. [FN5]

In February of 546 the plague struck close to the Imperial family, as Belisarius’s daughter Joannina fell sick and died of the illness. Belisarius was to have a church built for his beloved eldest daughter and, upon the chapel’s completion, would have her reburied within its walls. [FN6]

As the plague ravaged Rhomania, further weakening the Empire’s strength, it also began to move West, reaching Rome and Ravenna in September of 545 and Massalia and other major ports shortly thereafter. Much as it had in the East, the plague found a land which have been ravaged by years of war. From there it is thought to have reached as far away as Gaelia and Scandinavia. Although the estimated total number of dead in the West did not reach the same levels as in the East, this is because the population of the West was already substantially lower than that of the Eastern Empire.

It is believed that the Plague of Belisarius was the earliest outbreak out the Bubonic Plague.

The Glory of Emaneric’s Heirs: the Lectures of Dr. Valamir Fralet

Trans. Edwin Smith

Bern [OTL: Verona, Italy]: Skipmann and Sons Publishing, 1997

…

Theodemir had only just returned to Ravenna, following the conclusion of his campaign in Gaul, when news of the Plague first reached him. The first response by the King was remarkably similar to that of his Eastern counterpart, Belisarius, in that he quickly sealed the gates of the city and attempted to impose a rude form of quarantine, which he quickly abandoned when it became obvious that his efforts were for utterly ineffectual. The King’s second response, however, shines a bright light upon his character; he quickly ordered his two remaining sons out of the capital, sending them to a stronghold in the Alps, along with his wife. Having already lost one heir, he was unwilling to put his family in any more danger.

Rather than flee the capital himself, however, he declared his intention to stay and offer a steady hand to the citizens of the realm. Daily, it is recorded, mainly by Wulfila Strabo, of course, but others as well, Theodemir organized the relief effort, continuing to run the government as best he could, and making public appearances to maintain the people’s faith in him. This is likely what is remembered in the old folk story, of the King challenging Death to a duel for the lives of his countrymen. A less fantastic tale, albeit one that reveals a great deal of Theodemir’s character, was his public berating of a group of priests who refused to administer to the dying, for fear of losing their own lives. We also have evidence that the King petitioned the Arian Bishop of Ravenna, Fadar John, to give more support to the downtrodden and dying.

For months the plague raged and both Ravenna and Rome are said to have lost nearly 30 percent of their population. The effects were similar throughout Italy and Gothia, with Hispania likely suffering less than the other provinces. However, one of the most dramatic examples of the Plagues desolation was in northern Gaul. Having already suffered the full weight of Theodemir’s revenge against the Meroving Franks, the land now found itself being cleansed by the great sickness. Paris, once the capital of the Frankish kingdom had already been burnt by Theodemir, along with much of the countryside; now it was the plague’s turn to kill off the survivors of the war. Many survivors in Gaul blamed Theodemir for the plague, and believed it was a further step in his vengeance against the Franks and their Gaulish allies. The destruction was so great, that the modern name for the region Authia, stems from the ancient Gothic word Authida, which means ‘wasteland’. [FN7]

Meanwhile, in Britain, the plague appears to have caused renewed fighting between the Britons and the Saxon invaders, after years of stalemate. No one is quite sure why, or even if, the Britons were more greatly affected by the plague than their Germanic counterparts but, whatever the case, the Saxons were soon pressing deeper into Briton territory. [FN8]

The effects of Belisarius’ Plague upon the West were as great as those caused by the Great Death centuries later. The plague had struck a land already depopulated by years of war and a declining economy. To the North, much of Northern Gaul lay utterly in ruins and was depopulated. Although Hispania had emerged relatively unscathed, at least in comparison to the rest of the realm, the economy of the region had still been greatly affected, and there were rumors of renewed Suebian efforts to expand their territory into the rest of the peninsula. Gothia had been first harder, especially such cities as Ravenna and Masalia. However, it was to be the Romans of Italy, and the Kingdom’s urban centers, which would be struck the hardest by the Plague … [FN9]

[FN1] The Bucellarii in OTL are pretty much what is described here. I figure that this versatile force ends up becoming on the mainstays of the Rhomanian military and, as a result, coupled with the eventual romantic portrayal of Belisarius which emerges, they go one to be seen in a similar light to the Knights of OTL Europe. Of course, the Eastern Empire is hardly Feudal, and so the analogy only goes so far …

[FN2] I am not going to lie; I have very little background in military history, which is one of the reasons why my accounts of military encounters in this TL have been so vague. After looking at some maps of around Thessaloniki, Evropos appeared to be a good place for the armies to meet up. If anyone can suggest another place, or a more reasonable series of events, I am all ears!

[FN3] This is my attempt to try to reconstruct what a native Nordic phrase might be for “Norse Encyclopedia” (much like the Encyclopedia Britannica). Sadly, I don’t speak Old Norse (or even Icelandic), and so I went with an Icelandic translation of the phrase “Norse Lore Book”. Does it work? I don’t know! I’m certainly no linguist. But, hey, A for effort, right?

[FN4] The Plague of Justinian in OTL was largely as devastating as I’m describing it here. I’m of two minds over whether it would be better or worse in this ATL. On one hand, the Plague struck just as the height of the Gothic Wars, which had decimated Italy, giving a firm group for illness to spread. However, in the ATL, trade in the Mediterranean is going stronger than in OTL do to more stable trade networks, so it is likely spread faster and to different places. My eventual conclusion was that these factors would likely cancel one another out and leave us with a Plague that is pretty much as bad as in OTL (albeit, maybe, a bit more widespread, although there is some evidence of it hitting Ireland in OTL as well).

[FN5} Procopius in OTL and in this ATL views Belisarius as a bit of a weak willed buffoon, controlled by his evil, cheating, wife. As Belisarius is Emperor in the ATL, he had hushed up his feelings somewhat; but, as anyone who knows about the Secret Histories can tell you … somewhat wasn’t a lot for this guy. Oddly enough, Belisarius’ reputation continues to be strong to the present day in the ATL, which means Procopius, although still considered a good source for the time, is judged even harder than in OTL.

[FN6] In OTL, Belisarius had only one daughter with his wife. In the ATL he manages to have two. This is, of course, not that same daughter as OTL, as she was born after the POD, but simply shares a name with her OTL counterpart.

[FN7] This is my, likely silly, attempt to reconstruct a Gothic phrase and how it might be bastardized over time.

[FN8] In OTL, fighting between the Anglo-Saxons and British picked up right about this time as well, leading some to speculate that the Plague had have had a hand in doing this. In the ATL, the same thing occurs. My attitude is that the butterflies have yet to terribly impact what’s going on in Britain. They are having an impact, of course, and the same people being born in OTL and not going to show up in the ATL. But the broad trends are still roughly the same … for now.

[FN9] It just makes sense that the more ‘urban’ Roman populations would get hit harder than the more rural Gothic population at this point. Italy has certainly not been denuded of life (and is in much better shape than OTL at this same point), but the Romans definitely get hit moderately worse than their Gothic co-nationals. I suspect this will have a noticeable impact on how things develop.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

So, I lied. I had promised to look at the structure of the Gothic state during this update, but realized that I really needed to explain the Plague and its impact upon both the East and the West before I could really move forward with the narrative, after all. I hope you all forgive me!

In any case, after a year long hiatus, I just produced three chapters in about a week! Not too bad, if I do say so myself.

As always, comments, questions, random thoughts are always welcome! Feel free to fix my horrible attempts to butcher other languages or correct any details you feel just don't fit. I don't care; I just want comments!

Threadmarks

View all 89 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 83 Maybe Everything that Dies Someday Comes Back Chapter 84: Echoes of Future Past Interlude #1: The Map Chapter 17 Chapter 18 The Periphery Chapter 85: Of Sickness, Sorrow and Greatness Chapter 86 Heroes Always Get Remembered (Part 1: The Saga of Emperor Theodoric II) Chapter 87 The Bloody Verdict of Metz (The Saga of Emperor Theodoric II, Part 2)

Share: