Chapter Forty: The Battle of Golden Pond

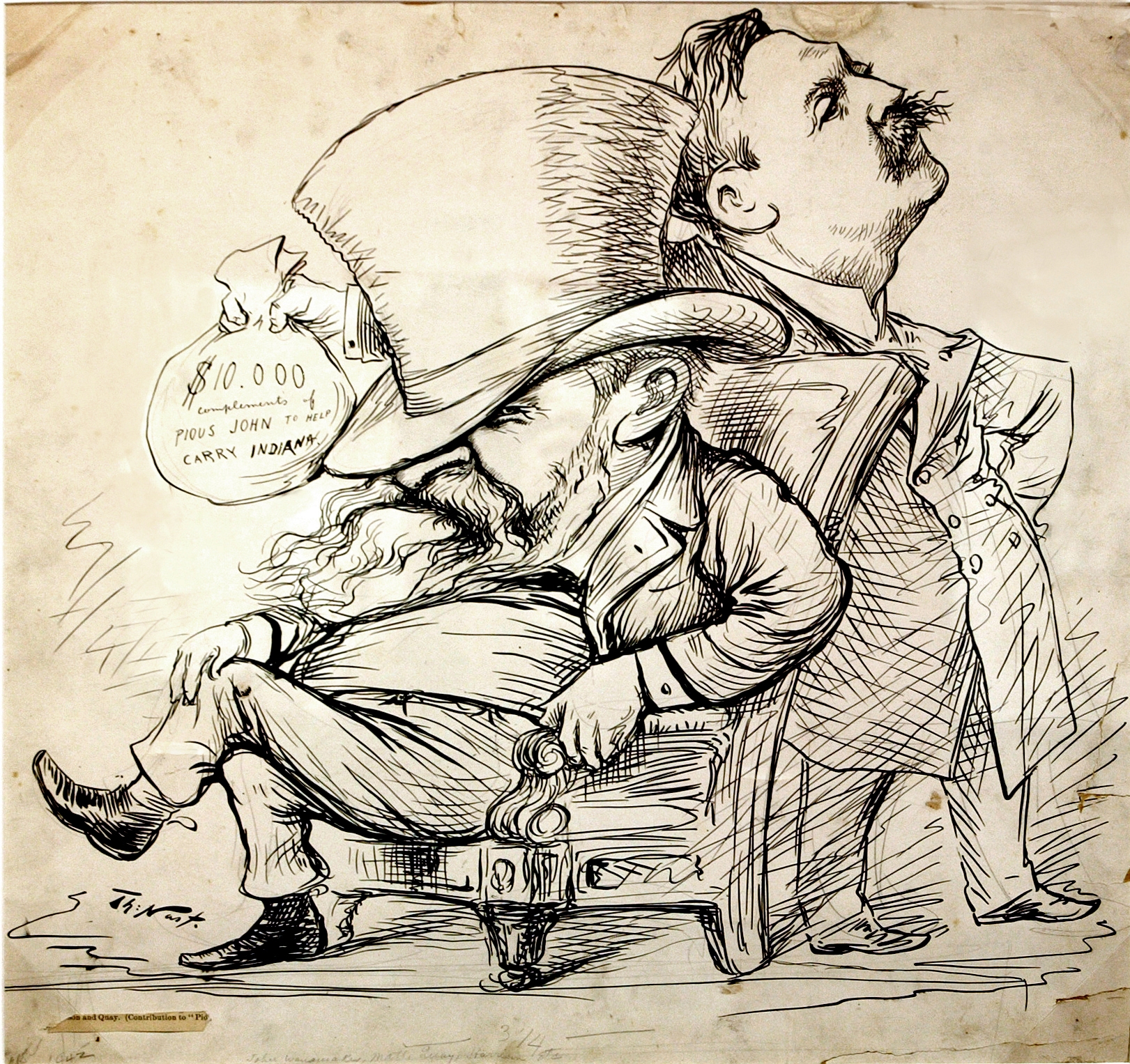

A Currier & Ives depiction of the Battle of Golden Pond

The Battle of Golden Pond would be the battle that decided the Confederate-American War. The seeds for the battle were planted in Sherman's capture of Nashville. With Nashville successfully in U.S. control, Sherman was in favor of an immediate push on to Chattanooga and Memphis, planning to send McPherson and the VI Corps to capture Memphis, while Sherman and the rest of the Army of the Cumberland moved to capture Chattanooga, which was the Confederacy strongest base in Tennessee after Nashville's fall. His plans, however, would be halted by President Conkling. Fearing a second CSA invasion of Pennsylvania following the Battle of Laurel, Conkling panicked and ordered Sherman to prepare his army to be transported east. Sherman, however, resisted this order, believing that a campaign into the Confederacy's heartland would be worth the risk of Jackson invading Pennsylvania. In arguing with Conkling over strategy, Sherman bought time for what he hoped would happen. Knowing that the Army of Tennessee was no longer a threat to him, and that the Army of the Susquehanna was no longer a threat to Jackson, he expected Jackson and his Army of Virginia to be transported West for a final showdown between the two victorious forces. Sherman's suspicion would prove correct, as in the aftermath of the Battle of Hickory Point, President Early and General Johnston were coordinating a movement of Jackson's forces west, while transporting the two weakest corps of the Army of Tennessee, the Florida and Mississippi, east to act as a garrison. The construction of railroad networks under the Breckinridge, Gordon, and Longstreet administrations were now being rewarded, as they allowed for this to happen. With this process in motion, Sherman was now able to point out to Conkling that the CSA was shifting its focus west.

An image of one of the CSA's trains and rail lines

Sherman realized, however, that the combination of the Army of Tennessee and Army of Virginia that he expected would put them in a slight numerical advantage over his Army of the Cumberland. He had a plan, however. He knew that in Southern Indiana there was a Reserve Corps under General Darius Couch. Its purpose was to help slow down a CSA invasion if they were to happen to allow for the regular U.S. army to arrive. Sherman planned to retreat north into Kentucky in conjunction with the Reserve Corps moving south, luring the Confederates after him, before linking up with the Reserve Corps and delivering a devastating blow to whatever CSA force followed him before cutting off the supply and communication lines of the battered force, which, leaving them in U.S. soil, would likely lead to their surrender. With in plan mind, Sherman was ready for when Jackson's men reached Tennessee. Jackson, meanwhile, combined the Armies of Virginia and Tennessee into one, forming the Army of the Confederacy. As a result of this, General Richard Taylor, former commander of the Army of Tennessee, was sent back down to his Louisiana corps command, and the two Cavalry Corps of the two armies were merged into one eight brigade corps under General Forrest. With almost all of the CSA's regular forces combined into one force, Jackson, based in Chattanooga, eyed Sherman and the Army of the Cumberland and planned his offensive action to regain Nashville.

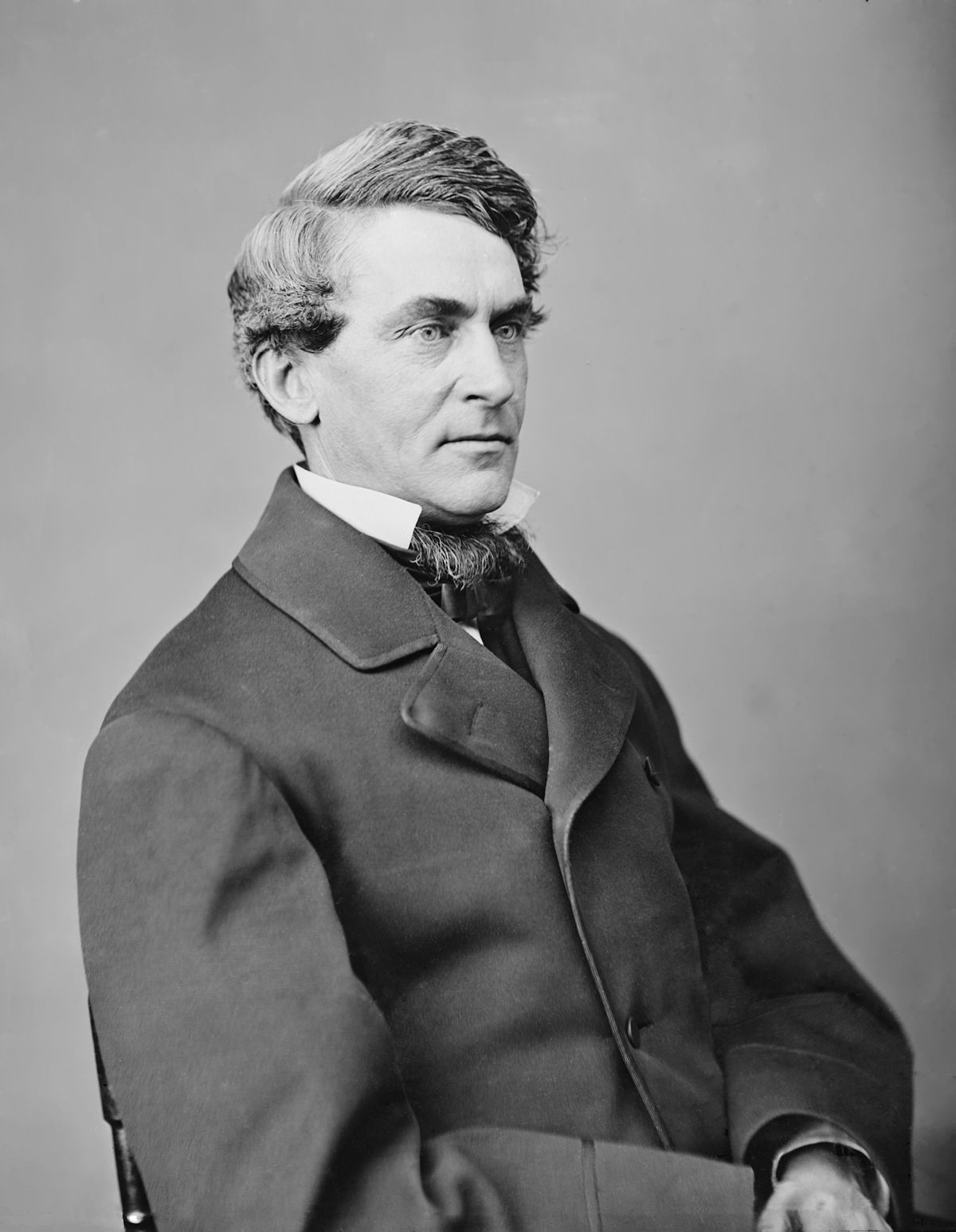

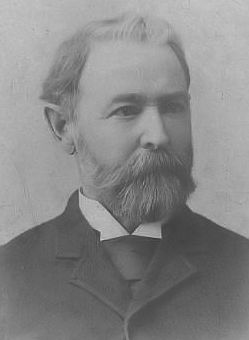

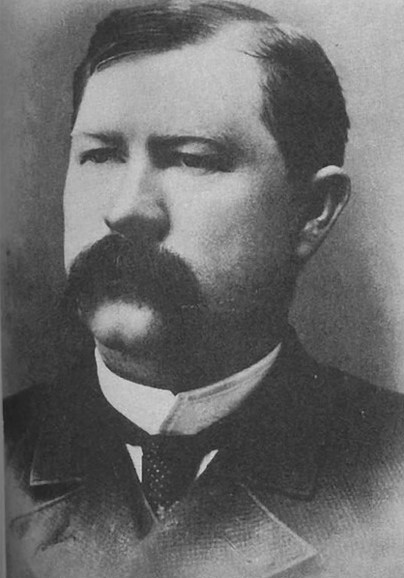

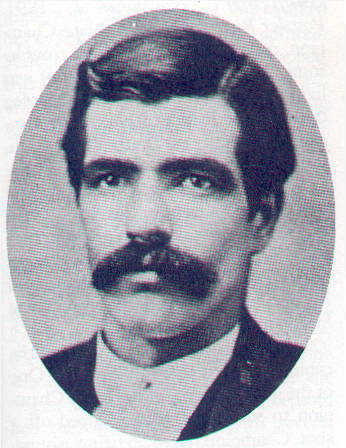

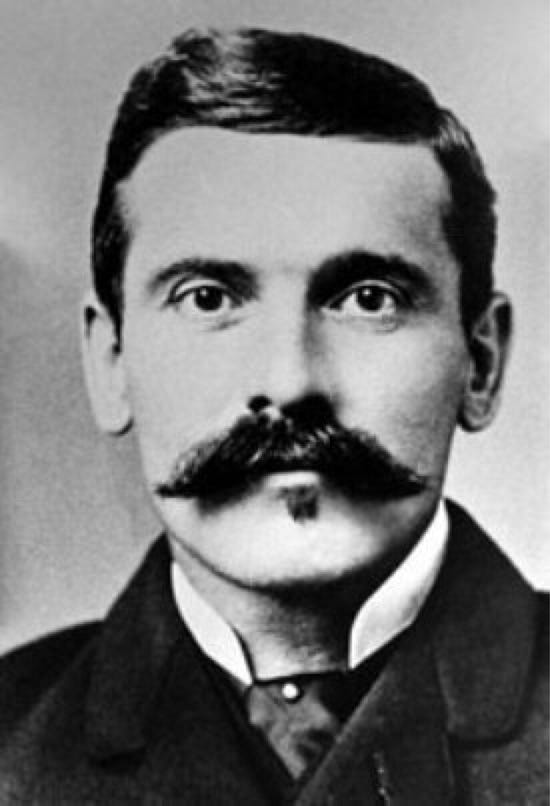

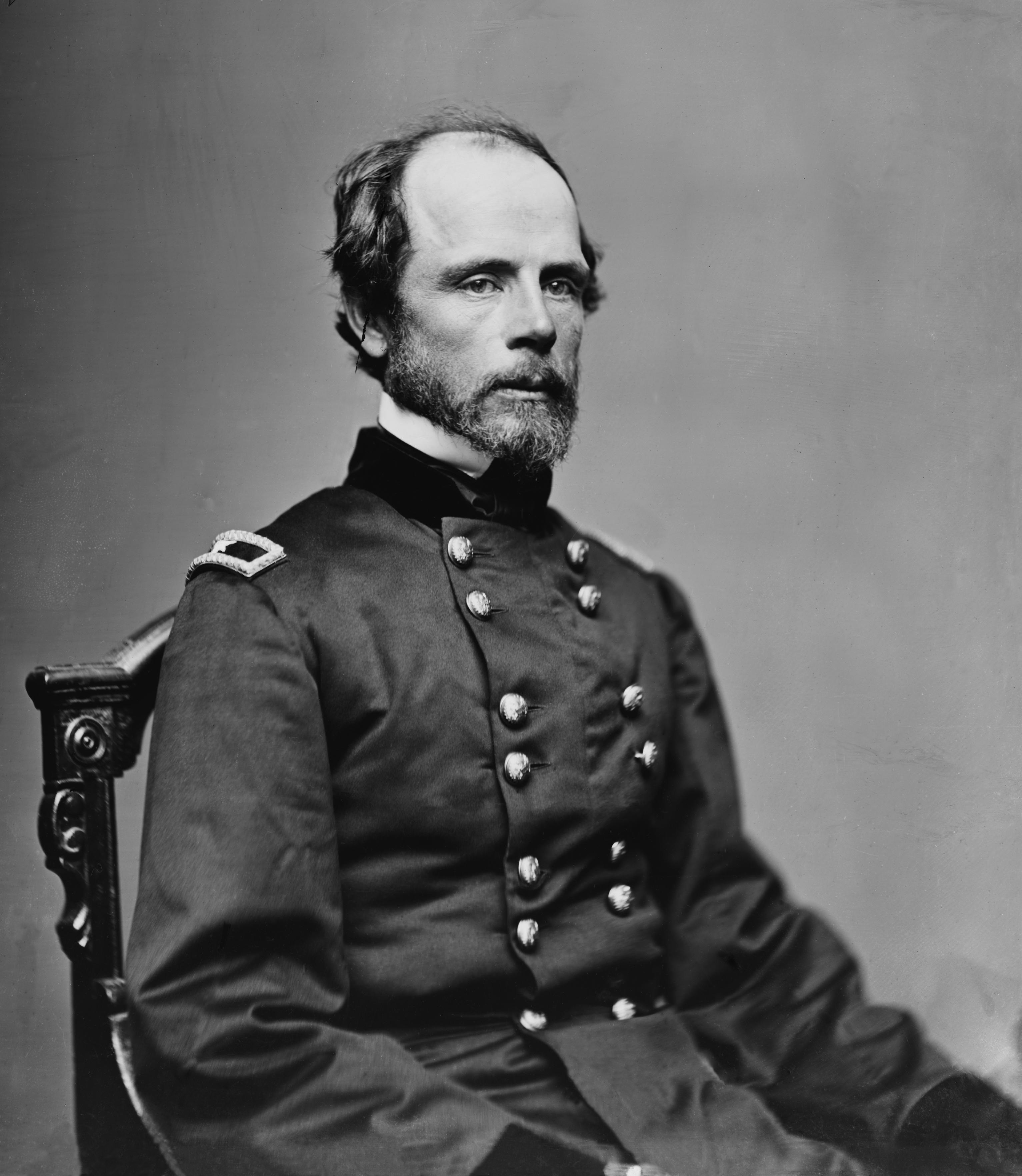

Darius Couch, Reserve Corps commander

Sherman would move first, however, beginning his planned feigned retreat north on October 17, 1886. Jackson moved rapidly also, recapturing Nashville following Sherman's abandonment of the city, which had been gutted from a month of serving as a U.S. encampment. Jackson would continue to follow Sherman north, falling for Sherman's trap. When Jackson reached the Tennessee border, some of his corps commander voiced concerns about invading U.S. territory and the consequences of defeat, but an ever confident Jackson continued to spur his Army of the Confederacy north into Kentucky. Eventually, on November 1, Sherman linked up with the Reserve Corps and halted his advance near the Kentucky town of Golden Pond on a open field. On November 3, Jackson and the Army of the Confederacy reached the outskirts of Sherman's position, and the time had come for a decision. Jackson could either attack Sherman, who now outnumbered him, or retreat back into Tennessee. As Sherman had expected, Jackson's aggressive nature won out, and he ordered his men to prepare for battle the next day, November 4.

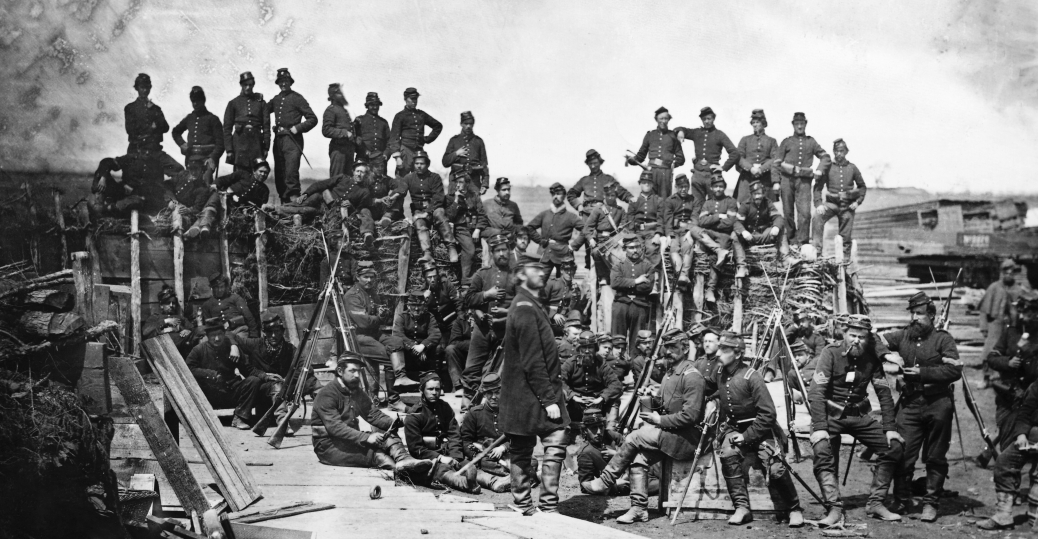

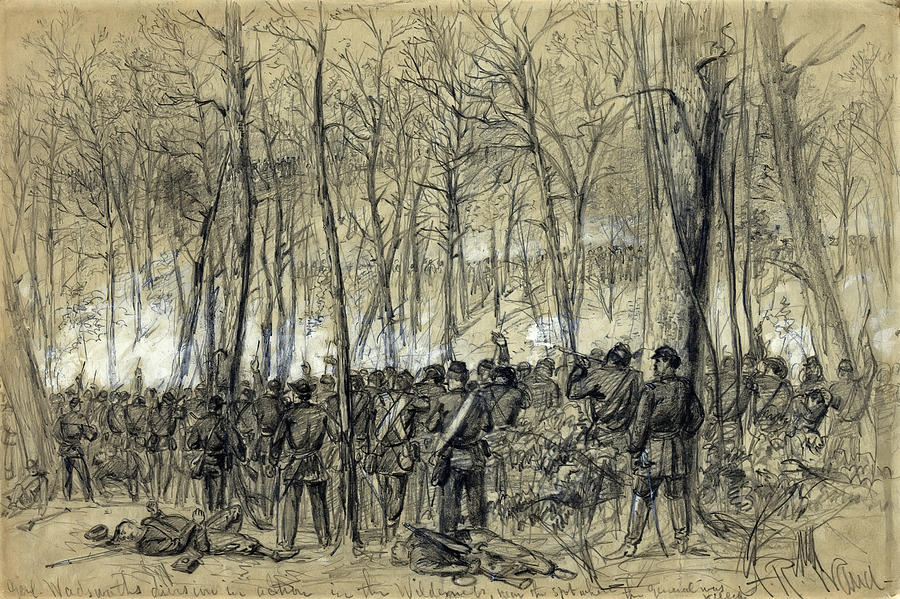

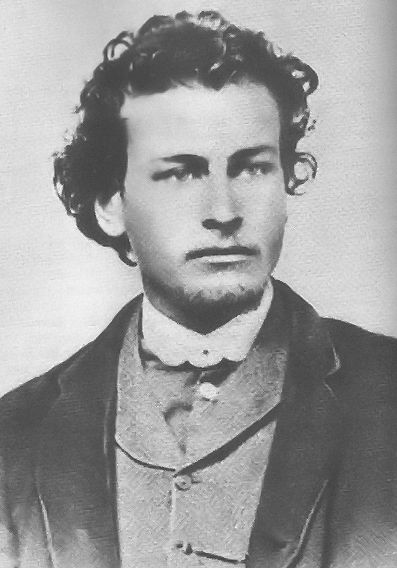

The U.S. Army of the Cumberland crossing a Tennessee River ford into Kentucky

Both sides deployed their forces for battle. Sherman placed his inexperienced Reserve Corps in the center, with two veteran corps to the left, the VI and VII Corps and right, the VIII and IX Corps, of each of its sides, with the Cavalry Corps deployed behind it. Jackson, meanwhile, deployed six of his corps, the Arkansas, North Carolina, Alabama, Texas, Virginia, Georgia, into a column on his left supported by the Cavalry Corps, while the South Carolina, Tennessee, Maryland, and Louisiana corps held his center. Jackson planned to use his six corps column to envelope the U.S. right, while his four corps line held against any U.S. assaults. Sherman, meanwhile, predicted that Jackson would attack, and had his men prepare for another defensive battle. This time, however, the Confederacy would not charge into his front. Upon seeing Jackson's column, under the direct command of General D.H. Hill, approach his right flank, Sherman altered his plan, and ordered McPherson and Cox to pull back their corps and refuse their flank in conjunction with the movements of Hill's column. At first, this plan would succeed, with McPherson and Cox acting in conjunction with each other and responding appropriate to the Confederate movements. Eventually, as the Confederates drew nearly and continually shifted their men continue to threaten the U.S. flank, McPherson and Cox failed to coordinate properly, and gap appeared in the U.S. line between their corps when McPherson began shifting without Cox prepared for it. Upon seeing this, Hill would order his men to attack the gap, abandoning their goal of the U.S. right. With this, his men flooded into the gap, and separated McPherson's corps from the rest of the U.S. line, with McPherson's situation only worsening when Hill shifted Hood's Texas and Cleburne's Arkansas corps to drive in on his flank. For a moment, it seemed like the whole U.S. line might be rolled up.

A Daniel Troiani painting depicting Hill's attack on the U.S. gap

McPherson's corps was doomed to near on destruction by the holding action they performed under attack from almost all sides, but it allowed for the rest of the U.S. forces to move into position and prepare. When the VI Corps finally collapsed and fled, the VII and Reserve Corps had managed to rotate to face in the direction Hill's column and had some time to prepare. But again disaster for the U.S. seemed to loom when Hood's Texas Corps seemed in prime position to attack the right of this new line. The savior of this line, however, would come from the men Sherman most likely least suspected, his Cavalry Corps under General Stanley. Seeing the new U.S. line in increasing danger, Stanley would order his Cavalry Corps to get around to the Confederate rear. Blocking his movement, however, was the legendary "Wizard of the Saddle" General Forrest. Stanley would none the less drive his forces right into Forrest's men, resulting in the largest cavalry action of the Confederate-American War. Surprised by the ferocity of the much maligned U.S. Cavalry, Forrest and his men were unprepared for Stanley and his men, with a charge from General Wilson's division breaking a hole through Forrest's line, sending half of his corps into retreat. Much enraged by this, Forrest would pull out the other half of his corps in an attempt to consolidate and rally his men. Ultimately, however, Forrest would find himself chasing the retreating half of his corps off the field, taking the CSA Cavalry Corps out of the battle and clearing the way for Stanley to attack the rear of Hood's Texans. The confusion caused by this bought Cox enough time to position his men in a way that Hood could not crush his flank. Stanley and his corps were only forced to pull out with the arrival of Cleburne's corps to the aid of Hood's, forcing Stanley to fall back to the main U.S. line.

General Stanley's Cavalry Corps attacking the unprepared rear of Hood's Texas Corps

With Confederate efforts frustrated on the right of the new U.S. line and Sherman rapidly moving the VIII and IX Corps into the unplanned formation, the opportunity presented by the line was rapidly evaporating. Seizing their final chances for a decisive action, General Hill allowed General Gordon to bring his men in a charge against the left of the new U.S. line, which was composed of the Reserve Corps. Both Hill and Gordon expected the inexperienced men to melt under a serious strain, and at first, their belief were proven true when Gordon's charge routed a division of the Reserve Corps under General John M. Schofield. Once again, however, an unexpected hero would rise for the U.S. troops. This time, it would be another division commander in the Reserve Corps: General Don C. Buell. Labeled a failure in the Civil War, General Buell considered it lucky that he managed to attain command of one of the Reserve Corps' divisions. Now came his chance to redeem himself. With Schofield's men in rout, Buell's division was next in line of Gordon's attack. Buell would calmly turn his regiments that were directly in the line of Gordon's attack and order them to charge. Once again, a sacrifice of lives would save the U.S. line, with the men who fell in the charge Buell ordered buying time for General Parke and the the IX Corps to position itself into the new line.

A painting depicting the suicidal charge of one of Buell's regiments that would ultimately save the line

With the failure of his assault, Gordon would fall back into line and soon engage with the rest of the former column in a brutal line battle with the U.S. line, as the VIII Corps arrived on the U.S. right and the IX Corps arrived on the U.S. left, while General Jackson sent the South Carolina, Tennessee, and Maryland corps to extend his lines to avoid them being flanked. Jackson, however, knew that in the line battle this was rapidly shaping up to be, the Confederacy could not outmatched the U.S., and that defeat was the likely result if no change were to occur. Jackson's decided that in order to win the battle, he was going to have to take his last reserve, the Louisiana Corps, and attack the left of the U.S. line in one final all out assault. Jackson decided to personally be with the men in the charge, with General Taylor being able to convince him that leading it from the front personally would be a bad idea. With this, Jackson and the Louisiana Corps charged towards the U.S. left. Again, it seemed that the Confederates were going to be able to wrap up the U.S. line, but in one final attack of bravery, General Stanley would again order his cavalry to charge, as they were the sole U.S. reserve, attacking the flank of Jackson attack. Unprepared for this, Jackson's assault was bogged down by this, buying time for Parke to turn some of his men and particularly some of his cannon into the Louisiana men and pound the corps into submission. With this, Jackson, whose hat and jacket were riddled with marks of bullets that had passed through them, ordered the Louisiana men to fall back, followed by a general order to his men with the same effect. The Battle of Golden Pond had narrowly gone in favor the U.S. forces.

A David Nance painting depicting the charge of the Louisiana corps

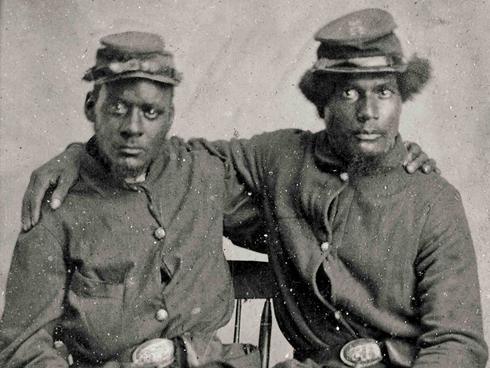

With Sherman's army unable to stop and only able to harass them after the brutal battle, Jackson's beaten forces slipped back into Tennessee much worse for wear, having suffered over 49,000 causalities in the battle and subsequent retreat. Among the battle's killed were General Hood of the Texas corps, and Arkansas corps division commanders Dandridge McRae and William Cabell. Among the injured were Generals D.H. Hill, Gordon, Rodes, Cleburne, and division commanders William D. Pender of North Carolina, William Bate of Tennessee, Hiram Granbury of Texas, States R. Gist of South Carolina, George T. Anderson of Georgia, and all three of the Louisiana's corps division commanders: Alfred Mouton, St. John Liddell, and Leroy Stafford. Maintaining control of the field, Sherman's forces were also battered, having suffered 42,000 casualities in the terrible fighting, and having Generals Grenville Dodge and E.R.S. Canby killed with Generals McPherson, Thomas J. Wood, Lew Wallace, Thomas E.G. Ransom, and Christopher C. Augur all going down wounded. The Battle of Golden Pond would be the bloodiest of any battle in the Western Hempshire. In its aftermath, both sides were horrified by the tremendous causalities, and soon peace movements in both the U.S. and CSA were strong both in the general populace and the government.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/55542665/1200px_1st_Minnesota_at_Gettysburg.0.jpg)