It's not really clear to me that this would be the case, considering how much of the tropics is affected by bad weather at times. A solar collector is going to be seriously thrown out of joint by monsoon season, for instance, given that we're talking about concentrating solar that can't tolerate cloudy weather as well as solar cells. I suspect it would be more that in certain applications where losing heat for a time might be considered tolerable for monetary savings (as you mentioned in the update, domestic hot water), or in certain places where the logistics are particularly difficult and solar is relatively available (deserts, certainly, perhaps some interior non-desert areas of Brazil, Southeast Asia, and Africa) solar could outcompete...at least for now.The way I see it, solar collector technology will result in a sort of "Economic Tropic", a limit where coal and fossil fuels can't economically compete in terms of sheer heat generation against solar energy at any time of the year.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Solar Dreams: a history of solar energy (1878 - 2025)

- Thread starter ScorchedLight

- Start date

-

- Tags

- chile mouchot solar energy

Threadmarks

View all 39 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

26: The Monster of Atacama 27: ADA Part 28: The purifying light Part 29: A Night to Remember Visual Document IV: The Aeromotor Generator in the US (ca. 1910 - 1940) Mini update: Solar Heat in the copper refining process 30: The glow in the desert Visual Document V: Cryogenically Treated RazorThat would certainly be good for their financial situation, but it might not be best for widespread dissemination and usage of the technology. Patents, by definition, make it harder for other people to copy and modify an invention or idea, so strong patent protections around it will put barriers in the way of people who want to experiment with the technology and see where it could be useful. A failure to protect would probably be better from the global point of view.I hope our Heroes can keep a lid on the licensing and patens for their work! Best get the designs registered in London, Paris, Washington DC, etc etc ASAP!

brotherWhere his borther had mechanical inclinations,

What about the actual Arctic, or close to it?there will be an "Economic Artic Circle" where solar production is just impractical.

In some places 24 hour sunlight, but will the boiler be able to keep the water in it from freezing?

And will being able to work 24 hours half the year make up for not working the other half?

It's not really clear to me that this would be the case, considering how much of the tropics is affected by bad weather at times. A solar collector is going to be seriously thrown out of joint by monsoon season, for instance, given that we're talking about concentrating solar that can't tolerate cloudy weather as well as solar cells. I suspect it would be more that in certain applications where losing heat for a time might be considered tolerable for monetary savings (as you mentioned in the update, domestic hot water), or in certain places where the logistics are particularly difficult and solar is relatively available (deserts, certainly, perhaps some interior non-desert areas of Brazil, Southeast Asia, and Africa) solar could outcompete...at least for now.

I wasn't implying that it'd follow the tropics as a hard rule, but more in the sense that latitude would be an important factor which sets where solar energy outperforms fossil fuels in heat generation.

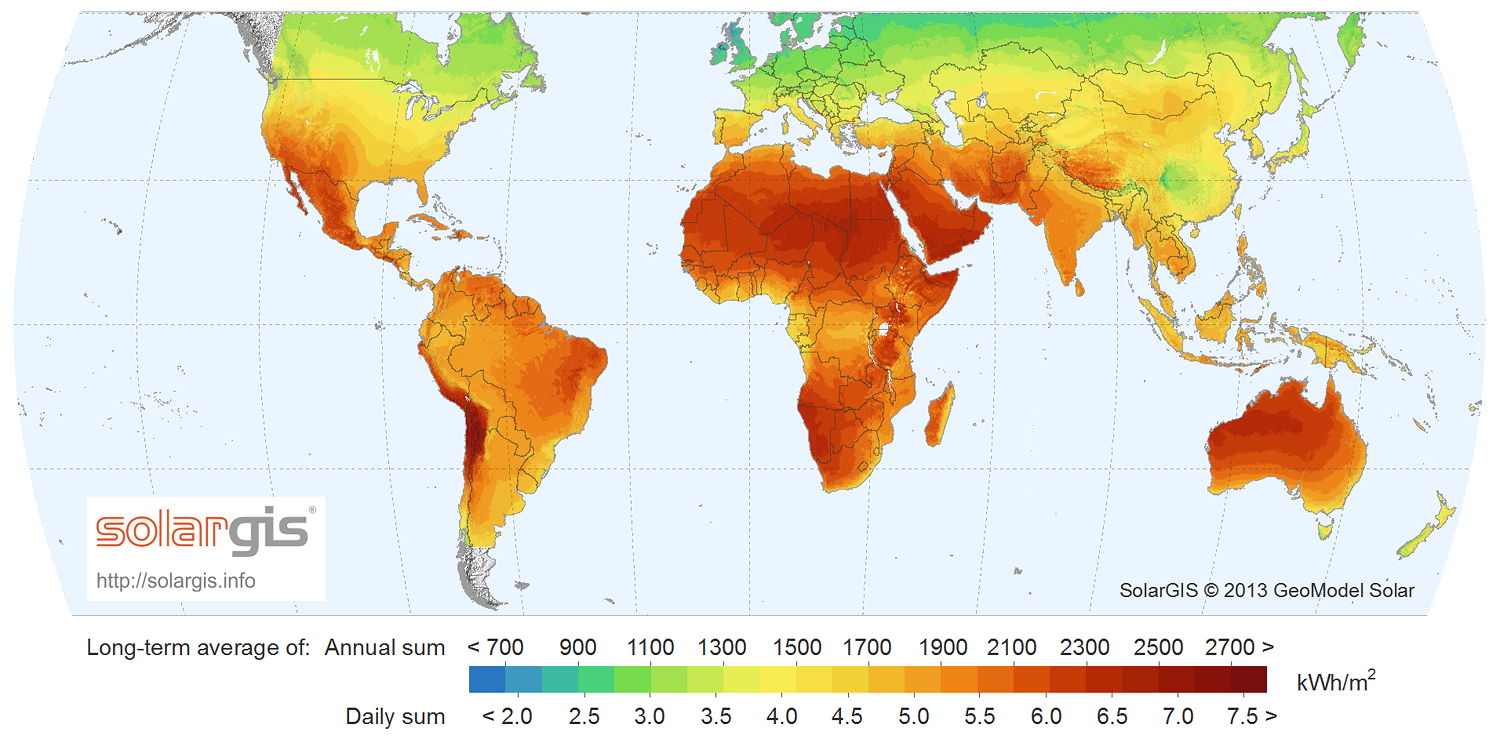

Bringing back the solar irradiance index,

Areas in red and orange is where solar will have a significant advantage over fossil fuels. Areas in yellow are places where solar will have to compete with fossil fuels, and areas in green will only see sparse use of solar energy in industrial scales, although increased interest in it will result in usage of solar heat for low temperature processes like wood drying or more efficient heating.

Climate, of course, will play a significant part on areas like India. In monsoon season the machines would be useless.

Intermitence will be a problem, too. But remember that this is largely a pre-electrical world, and heat (or even work) can be stored much more easily than electricity.

brother

What about the actual Arctic, or close to it?

In some places 24 hour sunlight, but will the boiler be able to keep the water in it from freezing?

And will being able to work 24 hours half the year make up for not working the other half?

For individual purposes? There are cases of solar collectors working without any problems in the artic right now. Woth proper orientation, they'll work just fine.

The problem is that you can't set many of those in a given area, which will make any large scale usage of solar power impossible in those places. No solar power plant for Anchorage or Punta Arenas.

Following the discovery of rich gold deposits in Kalgoorlie Western Australia at the end of the 19th century 600 km pipeline was built to supply water from the wetter coastal regions to miners in the parched interior. This massive feat of engineering required a number of pumping stations along the way which in this time line could make use of the solar powered engines. Australia has long had dreams of irrigating the inland and making the desert bloom, solar powered pumping stations could be seen as a means of doing so.

Part 7

Part 7: Irradiance

January, 1886

Almonte, Tarapacá.

It was after sunset, and when his machines stopped, so did Augustin. Things were, on the aggregate, going very well thanks to Serrano's business sense. The domestic heater went from prototype to validated design to commercially viable within two months, and they were selling about one hundred per month. The design was a simplification and miniaturization of the Mouchot-Puig boiler, encased within a mirrored double glass case to reduce loses due to irradiance and conduction. So long as the pipes could supply it with liquid water and there was at least some sunshine, the device would produce hot water even in extremely cold temperatures... or so did Puig said after testing it on the mountains. And, so long as people took care and stored it within their houses, that water could last until the next time it needed to be produced.

Mouchot wasn't entirely satisfied with his work. He came to work on the industry, and working at the domestic scale didn't satisfy him. But the money, at last, was starting to trickle in. Each month they sold a hundred or so water heaters, and the Franco-Chilean Solar Power Company (a name picked by Serrano, who thought it would sound better than the plain 'Solar Energy Company' he proposed) was employing fifty workers. In the middle of the desert.

Word was spreading far, as far as La Paz, at least. He had established correspondence with one of his clients, an Bolivian engineer by the name of Abelino López-Tikuña, who was concerned with the loss of access to the sea and international markets. Apparently, the man had a son whose health was greatly dependent on consumption of citrus fruit, for which he had built a greenhouse.

López-Tikuña had thought of a half-buried greenhouse, which would reduce the heat loss of the it and stabilize temperatures. He learned about Mouchot's experience with solar energy, and contacted him to see if the device could be improved.

Well, it could: first, they should align the long axis from east ho west. Secondly, they should tilt the roof to maximize solar absorption. And third, the structure that supported that tilted glass should be made of an insulating material, like bricks.

He hoped that his Bolivian colleague would find those suggestions useful, and asked him to write about the results.

All in all, things were going well for Augustin, if a little bit tedious at times. He still wasn't able to complete his dream of large scale solar power, but he could see himself doing it.

München, Imperial Germany

Klaus woke up early. He paid a knocker-up for it, because time was scarce and he couldn't afford to waste his time sleeping during winter. Most of the days, he thought he wasted that money as he went right back to sleep. His wife complained him about it, but in his research, every hour counted.

And today, all that 'wasted' money was finally giving the big return he needed. He woke up and saw Venus in the sky. The sky was clear, without a single cloud in the horizon.

Today it'd be colder than usual. The early morning was specially cruel, and he arrived at his laboratory with forst forming on his eyebrows. Maybe two hours before sunrise, enough to check the Stirling engine for work, do some calibration on the rig, and clean the (cracked) 1.5 M mirror he had acquired. It was a shame that such a magnificent tool of science became useless for its purpose, but Klaus wasn't interested in precision, only that it could concentrate sunlight into a single point. It was ironic, or so Klaus thought, that the Stirling engine once belonged to a church, used to power an organ.

Klaus couldn't help but admire Mouchot. The frenchman was abrassive and rude and probablt crazy to set up shop in that godforsaken desert, but he had stumbled upon something big. The captured solar concentrator was flawed. It was too inefficient. It relied on steam and wasted too much material. Improving it was easy. Klaus knew it, and he didn't doubt that Mouchot did as well.

And that it did quite well still. Using two cranks, he aimed the mirror towards the morning brilliance, and waited for the sun to rise. The sunrays fist touched the ceiling of this laboratory, then they descended down the wall and only the started to touch the parabolic mirror. The hot part of the stirling engine began to glow with the reflected light, until it shone like a second sun, smaller and much dimmer. Only a small tap on the flywheel, and the engine woke up. It would stay awake the whole day.

Early 1886 was a time of gradual expansion and consolidation of Mouchot's work. Certainly, it was during this period that his first profitable venture became widespread, with the 'Domestic Boiler' (soon shortened to the 'Domestica') seeing an enormous demand all around Chile. In a time when few homes could afford a wood or coal boiler, and boiling water over a fire was dangerous, the Domestica became an essential part of any well-to-do household. Although today we can see its shortcomings (most notably, the significant loss in efficiency during cloudy days) during this period it became the best alternative for water heating, and in some cases the only affordable one. Even La Moneda, the Chilean Presidential palace, would later install one, to the infinite joy of Augustin Mouchot.

On a curious note, epistolar evidence has recently surfaced that reveals a rich interaction between Mouchot and López-Tikuña, the inventor of the Walipini Greenhouse which would later revolutionize fruit production throughout the northern hemisphere.

Also during this time, Dr Klaus Hess perfected earlier works by Mouchot. Interestingly, Hess experience was the polar opposite of his French pair, having secured an adequate grant by the Leopoldina to research solar energy concentrators, but severely lacking sunlight for a good part of the year. Even with this severe limitation, the work or Dr. Hess would provide one of the definitive designs of solar concentrators, one which hasn't changed much in almost 140 years.

January, 1886

Almonte, Tarapacá.

It was after sunset, and when his machines stopped, so did Augustin. Things were, on the aggregate, going very well thanks to Serrano's business sense. The domestic heater went from prototype to validated design to commercially viable within two months, and they were selling about one hundred per month. The design was a simplification and miniaturization of the Mouchot-Puig boiler, encased within a mirrored double glass case to reduce loses due to irradiance and conduction. So long as the pipes could supply it with liquid water and there was at least some sunshine, the device would produce hot water even in extremely cold temperatures... or so did Puig said after testing it on the mountains. And, so long as people took care and stored it within their houses, that water could last until the next time it needed to be produced.

Mouchot wasn't entirely satisfied with his work. He came to work on the industry, and working at the domestic scale didn't satisfy him. But the money, at last, was starting to trickle in. Each month they sold a hundred or so water heaters, and the Franco-Chilean Solar Power Company (a name picked by Serrano, who thought it would sound better than the plain 'Solar Energy Company' he proposed) was employing fifty workers. In the middle of the desert.

Word was spreading far, as far as La Paz, at least. He had established correspondence with one of his clients, an Bolivian engineer by the name of Abelino López-Tikuña, who was concerned with the loss of access to the sea and international markets. Apparently, the man had a son whose health was greatly dependent on consumption of citrus fruit, for which he had built a greenhouse.

López-Tikuña had thought of a half-buried greenhouse, which would reduce the heat loss of the it and stabilize temperatures. He learned about Mouchot's experience with solar energy, and contacted him to see if the device could be improved.

Well, it could: first, they should align the long axis from east ho west. Secondly, they should tilt the roof to maximize solar absorption. And third, the structure that supported that tilted glass should be made of an insulating material, like bricks.

He hoped that his Bolivian colleague would find those suggestions useful, and asked him to write about the results.

All in all, things were going well for Augustin, if a little bit tedious at times. He still wasn't able to complete his dream of large scale solar power, but he could see himself doing it.

München, Imperial Germany

Klaus woke up early. He paid a knocker-up for it, because time was scarce and he couldn't afford to waste his time sleeping during winter. Most of the days, he thought he wasted that money as he went right back to sleep. His wife complained him about it, but in his research, every hour counted.

And today, all that 'wasted' money was finally giving the big return he needed. He woke up and saw Venus in the sky. The sky was clear, without a single cloud in the horizon.

Today it'd be colder than usual. The early morning was specially cruel, and he arrived at his laboratory with forst forming on his eyebrows. Maybe two hours before sunrise, enough to check the Stirling engine for work, do some calibration on the rig, and clean the (cracked) 1.5 M mirror he had acquired. It was a shame that such a magnificent tool of science became useless for its purpose, but Klaus wasn't interested in precision, only that it could concentrate sunlight into a single point. It was ironic, or so Klaus thought, that the Stirling engine once belonged to a church, used to power an organ.

Klaus couldn't help but admire Mouchot. The frenchman was abrassive and rude and probablt crazy to set up shop in that godforsaken desert, but he had stumbled upon something big. The captured solar concentrator was flawed. It was too inefficient. It relied on steam and wasted too much material. Improving it was easy. Klaus knew it, and he didn't doubt that Mouchot did as well.

And that it did quite well still. Using two cranks, he aimed the mirror towards the morning brilliance, and waited for the sun to rise. The sunrays fist touched the ceiling of this laboratory, then they descended down the wall and only the started to touch the parabolic mirror. The hot part of the stirling engine began to glow with the reflected light, until it shone like a second sun, smaller and much dimmer. Only a small tap on the flywheel, and the engine woke up. It would stay awake the whole day.

Early 1886 was a time of gradual expansion and consolidation of Mouchot's work. Certainly, it was during this period that his first profitable venture became widespread, with the 'Domestic Boiler' (soon shortened to the 'Domestica') seeing an enormous demand all around Chile. In a time when few homes could afford a wood or coal boiler, and boiling water over a fire was dangerous, the Domestica became an essential part of any well-to-do household. Although today we can see its shortcomings (most notably, the significant loss in efficiency during cloudy days) during this period it became the best alternative for water heating, and in some cases the only affordable one. Even La Moneda, the Chilean Presidential palace, would later install one, to the infinite joy of Augustin Mouchot.

On a curious note, epistolar evidence has recently surfaced that reveals a rich interaction between Mouchot and López-Tikuña, the inventor of the Walipini Greenhouse which would later revolutionize fruit production throughout the northern hemisphere.

Also during this time, Dr Klaus Hess perfected earlier works by Mouchot. Interestingly, Hess experience was the polar opposite of his French pair, having secured an adequate grant by the Leopoldina to research solar energy concentrators, but severely lacking sunlight for a good part of the year. Even with this severe limitation, the work or Dr. Hess would provide one of the definitive designs of solar concentrators, one which hasn't changed much in almost 140 years.

Last edited:

Very nice update. Good to see the boilers beginning to spread and the inventors earn cash.

Germany while an innovative place at times isn’t going to be the best place for solar, but taking over from fossil fuels during the day will cut deforestation and coal mining a lot.

Those greenhouses are very interesting.

More please!

Germany while an innovative place at times isn’t going to be the best place for solar, but taking over from fossil fuels during the day will cut deforestation and coal mining a lot.

Those greenhouses are very interesting.

More please!

Very nice update. Good to see the boilers beginning to spread and the inventors earn cash.

Germany while an innovative place at times isn’t going to be the best place for solar, but taking over from fossil fuels during the day will cut deforestation and coal mining a lot.

Those greenhouses are very interesting.

More please!

The Walipini is a dead-simple design that was only invented in 1993. In this timeline, a similar design is prefected in Bolivia and further enhanced by Mouchot's input. However, the primary advantage of the design - and future developments - won't be related to solar energy. Thus, it is a footnote for the story.

Here's an example of a walipini-like design in action, and the enormous economic advantages it has over conventional fruit production:

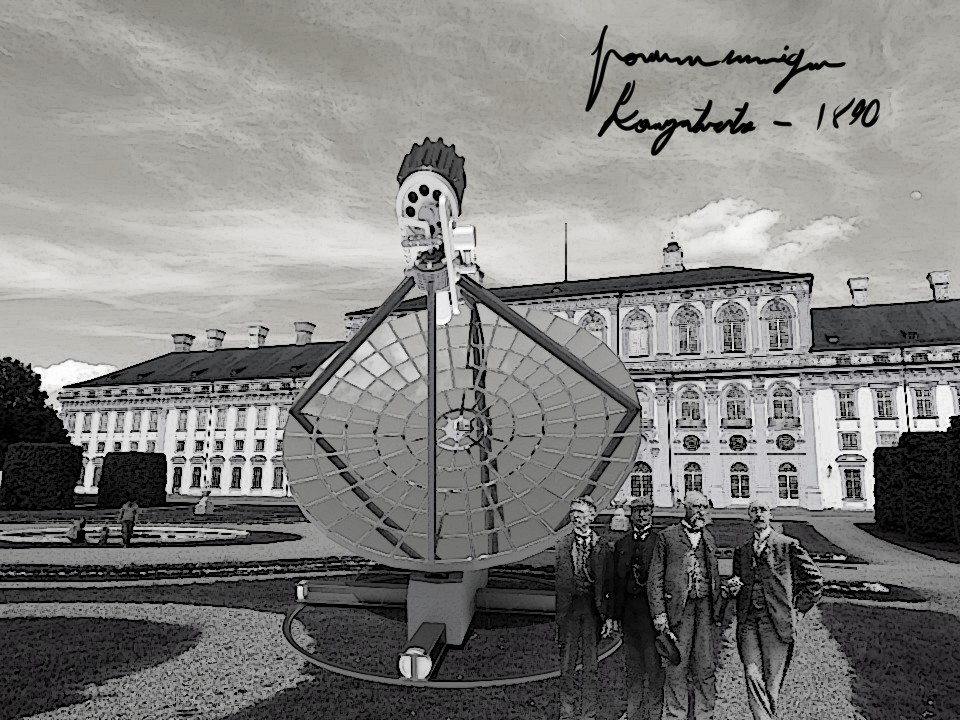

Visual Document I: Hess' Solarenergie-Konzentrator

Dr Hess and unidentified people at the Schleissheim Palace in München, 1890.

This is the second iteration of Hess Solar Concentrator, optimized for electrical generation. The Solarenergie-Konzentrator saw widespread use in German West Africa during the 1890s, where it provided cheap energy for industrial and agricultural purposes.

Reminds me of a telescope... well fundamentally both focus light.

Anyways, thank you for the visual reference.

German west Africa, that'd be OTL Cameroon and the surroundings. I admit I know almost nothing about that region OTL. I only know a bit about East Africa (somewhat competantly run, badass Lettow-Vorbeck) and South-West Africa (Herero Genocide Lots of desert there though, anything using the solar concentrator on?) Did TTL's Berlin Conference divide Africa the same as OTL?

Lots of desert there though, anything using the solar concentrator on?) Did TTL's Berlin Conference divide Africa the same as OTL?

Anyways, thank you for the visual reference.

German west Africa, that'd be OTL Cameroon and the surroundings. I admit I know almost nothing about that region OTL. I only know a bit about East Africa (somewhat competantly run, badass Lettow-Vorbeck) and South-West Africa (Herero Genocide

The Walipini is a dead-simple design that was only invented in 1993. In this timeline, a similar design is prefected in Bolivia and further enhanced by Mouchot's input. However, the primary advantage of the design - and future developments - won't be related to solar energy. Thus, it is a footnote for the story.

Here's an example of a walipini-like design in action, and the enormous economic advantages it has over conventional fruit production:

I have seen the design it would be very useful in Europe, but the place where it could be really revolutionary would be Japan and Iceland with their cold climate hand and large geothermal energy. If we see this introduced to Scandinavia in the late 19th century, they would likely explode in use under the Great War if it still happens. One major benefit of this design is that it reward small farms or farms with little productive soil, as they had a high labor amount to productive land. This means that smaller farms suddenly becomes far more economic viable. This would both have political and social consequences, the social consequences is the most clear, as small farmers tended to have larger families and with a need for labor they would have greater need for large families. But it also mean that they can marry earlier as smaller farms are cheaper and more viable. The political consequences differ from country to country.

International if the Great War still happens, the fact that Sweden and Norway can increase their agricultural production and export to Germany will also have some military consequences, as Germany can better feed its population even with the British blockage.

Dr Hess and unidentified people at the Schleissheim Palace in München, 1890.

This is the second iteration of Hess Solar Concentrator, optimized for electrical generation. The Solarenergie-Konzentrator saw widespread use in German West Africa during the 1890s, where it provided cheap energy for industrial and agricultural purposes.

Will this lead to a bigger German population there?

I have seen the design it would be very useful in Europe, but the place where it could be really revolutionary would be Japan and Iceland with their cold climate hand and large geothermal energy. If we see this introduced to Scandinavia in the late 19th century, they would likely explode in use under the Great War if it still happens. One major benefit of this design is that it reward small farms or farms with little productive soil, as they had a high labor amount to productive land. This means that smaller farms suddenly becomes far more economic viable. This would both have political and social consequences, the social consequences is the most clear, as small farmers tended to have larger families and with a need for labor they would have greater need for large families. But it also mean that they can marry earlier as smaller farms are cheaper and more viable. The political consequences differ from country to country.

International if the Great War still happens, the fact that Sweden and Norway can increase their agricultural production and export to Germany will also have some military consequences, as Germany can better feed its population even with the British blockage.

(Posted prematurely, that's why you have a weird notification)

To be honest, I only have a faint idea of what will happen in the next 30 or so years, because I intend for the Butterflies to flap very intensely in this timeline.

The direction it is taking, however, is one where fossil fuels face much greater and earlier competition from renewable sources.

The earlier development of the Walipini, for example, has a double significance:

1.- It shifts economies of scale back to small producers. A small farmer and his family could provide fruit year round even in colder climates. Their operations are more profitable than the United Fruit Company, and could outcompete them in price if it came to it.

Secondary effects of this is a much more stable Latin America, without the UFC having the resources of OTL. Another effect would be a more varied diet, and more ingredients for local cuisines. Also, less need for refrigeration.

2.- The Walipini strongly hints towards the use of geothermal energy. Not like the one found on Iceland (a country which I'd rather not speak of, for personal reasons

As for how these renewable technologies would affect international relations, that's also something I can't answer confidently without further research and worldbuilding. The most obvious is that reduced dependency on fossil fuels will be a relief to countries that don't produce them, and previously unimportant desert zones become much more valuable. The French would want to hold to Algeria much longer, Namibia might see far heavier industrialization, Chile will probably look at those nitrate fields and say "you know what? Keep them. We have more important things to do anyways." and begin a serious effort of industrialization. And so on and so forth.

Reminds me of a telescope... well fundamentally both focus light.

Anyways, thank you for the visual reference.

German west Africa, that'd be OTL Cameroon and the surroundings. I admit I know almost nothing about that region OTL. I only know a bit about East Africa (somewhat competantly run, badass Lettow-Vorbeck) and South-West Africa (Herero GenocideLots of desert there though, anything using the solar concentrator on?) Did TTL's Berlin Conference divide Africa the same as OTL?

It will take a few updates to get to the 1890s. I'm still focusing on Mouchot's development of solar technology in Tarapacá, but by 1888 the updates should take a more global tone.

And yes, colonialism will play a large role in those years.

Also, less need for refrigeration.

Hmm. I believe by far the major driver of refrigeration is meat

I would be cautious in assuming that this development will greatly shift the economics of fruit production; to use an example from OTL, while the Dutch have become major agricultural producers due to the use of greenhouses, they haven't completely replaced growing food in (in their case) southern and central Africa and shipping or flying it north to Europe. The thing is that the efficiency of agricultural production is not something you can just sum up by saying "this is more efficient" or "this is less efficient," but rather depends on what resources you're looking to use efficiently. Specifically, there's really four kinds of efficiency in agriculture: labor efficiency, land efficiency, capital efficiency, and natural resource efficiency (mostly water, especially groundwater). Often, there are significant tradeoffs between these kinds of efficiency--being highly land efficient, for instance, usually requires large labor inputs.1.- It shifts economies of scale back to small producers. A small farmer and his family could provide fruit year round even in colder climates. Their operations are more profitable than the United Fruit Company, and could outcompete them in price if it came to it.

Secondary effects of this is a much more stable Latin America, without the UFC having the resources of OTL. Another effect would be a more varied diet, and more ingredients for local cuisines. Also, less need for refrigeration.

To see an example of this in action, compare the modern American grain farm to a subsistence agricultural producer. The former is very labor efficient, in general--only a handful of farmers are needed to produce a large amount of food. But this comes at the cost of using huge amounts of land, massive amounts of capital (in the form of agricultural equipment and chemicals), and generally poor natural resource efficiency (albeit somewhat depending on where the farm is located). The latter, meanwhile, tends to be quite efficient with land and certainly very efficient with capital and resource inputs, since the subsistence grower can't afford to smother their problems in machinery and chemicals or dig hugely deep wells or anything like that. But typically they require a lot of labor as a result. It's hard to say that one is more efficient in general than the other, because they're optimizing for their particular economic situation: the United States has expensive labor and a lot of wealth, so optimizing on labor costs makes economic sense, whereas the subsistence producer has cheap labor and little wealth, so it makes more sense to substitute labor for capital.

When it comes to United Fruit they have the advantage over greenhouse producers of economizing on several of these axes simultaneously. Most obviously, since they're growing bananas (or coffee, pineapples, etc.) in a natural tropical environment they have lower capital costs--they don't need to build greenhouses at all. Since they're growing those foods with poor Central Americans instead of rich Estadounidese, they have lower labor costs. The fertility of the land and tropical environment also mean relatively efficient use of land and natural resources, too. So I suspect that they would be able to outcompete domestic producers of those same goods, even without taking into account corporate naughtiness like dumping to drive greenhouse producers out of business or the like, or things like microclimate effects on coffee flavor (since that wouldn't really be a point of interest for a hundred years or so).

Moreover, United Fruit also has another advantage over domestic producers--it has a distribution network. That's actually quite a hard problem to crack, and gives them multiple options to adjust and stick around. If these greenhouses really do shift things in a big way towards small producers, then they can shift into being a processor and distributor rather than a producer, as they did in reality eventually. This would still give them huge influence in Central American politics, unfortunately, as long as agricultural production for export remains an important part of their economies.

That's a very good point.To see an example of this in action, compare the modern American grain farm to a subsistence agricultural producer. The former is very labor efficient, in general--only a handful of farmers are needed to produce a large amount of food. But this comes at the cost of using huge amounts of land, massive amounts of capital (in the form of agricultural equipment and chemicals), and generally poor natural resource efficiency (albeit somewhat depending on where the farm is located). The latter, meanwhile, tends to be quite efficient with land and certainly very efficient with capital and resource inputs, since the subsistence grower can't afford to smother their problems in machinery and chemicals or dig hugely deep wells or anything like that. But typically they require a lot of labor as a result. It's hard to say that one is more efficient in general than the other, because they're optimizing for their particular economic situation: the United States has expensive labor and a lot of wealth, so optimizing on labor costs makes economic sense, whereas the subsistence producer has cheap labor and little wealth, so it makes more sense to substitute labor for capital.

I would be cautious in assuming that this development will greatly shift the economics of fruit production; to use an example from OTL, while the Dutch have become major agricultural producers due to the use of greenhouses, they haven't completely replaced growing food in (in their case) southern and central Africa and shipping or flying it north to Europe. The thing is that the efficiency of agricultural production is not something you can just sum up by saying "this is more efficient" or "this is less efficient," but rather depends on what resources you're looking to use efficiently. Specifically, there's really four kinds of efficiency in agriculture: labor efficiency, land efficiency, capital efficiency, and natural resource efficiency (mostly water, especially groundwater). Often, there are significant tradeoffs between these kinds of efficiency--being highly land efficient, for instance, usually requires large labor inputs.

To see an example of this in action, compare the modern American grain farm to a subsistence agricultural producer. The former is very labor efficient, in general--only a handful of farmers are needed to produce a large amount of food. But this comes at the cost of using huge amounts of land, massive amounts of capital (in the form of agricultural equipment and chemicals), and generally poor natural resource efficiency (albeit somewhat depending on where the farm is located). The latter, meanwhile, tends to be quite efficient with land and certainly very efficient with capital and resource inputs, since the subsistence grower can't afford to smother their problems in machinery and chemicals or dig hugely deep wells or anything like that. But typically they require a lot of labor as a result. It's hard to say that one is more efficient in general than the other, because they're optimizing for their particular economic situation: the United States has expensive labor and a lot of wealth, so optimizing on labor costs makes economic sense, whereas the subsistence producer has cheap labor and little wealth, so it makes more sense to substitute labor for capital.

When it comes to United Fruit they have the advantage over greenhouse producers of economizing on several of these axes simultaneously. Most obviously, since they're growing bananas (or coffee, pineapples, etc.) in a natural tropical environment they have lower capital costs--they don't need to build greenhouses at all. Since they're growing those foods with poor Central Americans instead of rich Estadounidese, they have lower labor costs. The fertility of the land and tropical environment also mean relatively efficient use of land and natural resources, too. So I suspect that they would be able to outcompete domestic producers of those same goods, even without taking into account corporate naughtiness like dumping to drive greenhouse producers out of business or the like, or things like microclimate effects on coffee flavor (since that wouldn't really be a point of interest for a hundred years or so).

Moreover, United Fruit also has another advantage over domestic producers--it has a distribution network. That's actually quite a hard problem to crack, and gives them multiple options to adjust and stick around. If these greenhouses really do shift things in a big way towards small producers, then they can shift into being a processor and distributor rather than a producer, as they did in reality eventually. This would still give them huge influence in Central American politics, unfortunately, as long as agricultural production for export remains an important part of their economies.

I agree, but it’s also a question of the crop, as example for banana light is more important than heat, as such bananas grown in a heated greenhouse in Europe have a smaller crop yield than banana grown in Africa. As a general rule tropical fruits with several annual harvests do less well, while annual vegetable, fruit and berry crops do far better. So things like chocolate nut, banana etc. will only be grown in war time, where access abroad is limited, while tomato, pepper, cucumber, strawberries, grapes, oranges, salats and similar crops[1] will be competitive or better even in peace time. What these walipini truly offer is a longer growing season and that the plants aren’t exposed to below freezing temperatures. The latter make it possible to grow orange and other citrus fruit (which are very cold weather intolerant) further north, while the latter offer that mediterranean crops can be grown north of the Alps and greater yield for local crops. I think that tomatoes will be one of them more interesting crop, as it over its growing season allow continued harvests and that it‘s relative easy to conserve and it’s a common filling product in other food conservation. So dishes you could see evolve would be Scandinavian goulash mixing tomato heavily with the pepper, different seafood like herring, mussel, clay fish and cod conserved in tomato sauce.

[1] pretty much any crop growing in Europe or USA.

Threadmarks

View all 39 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

26: The Monster of Atacama 27: ADA Part 28: The purifying light Part 29: A Night to Remember Visual Document IV: The Aeromotor Generator in the US (ca. 1910 - 1940) Mini update: Solar Heat in the copper refining process 30: The glow in the desert Visual Document V: Cryogenically Treated Razor

Share: