Unfortunately many people (many of whom have political power) buy into the GI Joe myth that America can wave a magic wand and the North Korean military will collapse overnight like Panama or Grenada.The base assumption is still that it will be a death-ride no matter who starts it and both sides are going to assume and act on that fact from the get-go.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Second Korean War in 1997

- Thread starter Gillan1220

- Start date

Unfortunately many people (many of whom have political power) buy into the GI Joe myth that America can wave a magic wand and the North Korean military will collapse overnight like Panama or Grenada.

I'd argue it's less myth than simply not having any experience fighting a conflict with anything approaching a 'peer' enemy along with willfully believing "nobody would be that stupid" when the facts tend the other direction

Randy

Just curious, doesn't the KPA suffer from logistics in longer protracted war? Especially since their fuel is limited and their soldiers much less their people aren't well fed?Unfortunately many people (many of whom have political power) buy into the GI Joe myth that America can wave a magic wand and the North Korean military will collapse overnight like Panama or Grenada.

Just curious, doesn't the KPA suffer from logistics in longer protracted war? Especially since their fuel is limited and their soldiers much less their people aren't well fed?

The general intel says they will hit a point in a couple of days at most they will be "living off the land" and stripping South Korea for support. "In theory" they expected them to start loosing cohesion as this goes on. It's arguable if they can actually launch an attack and more likely to stand on the defensive. YMMV

Randy

In most modern "continuation of the Korean War" scenario, it always has the KPA loosing their cohesion in a week or two. Then you'd have thousands of KPA soldiers surrendering to the U.S./ROK with nothing but white flag and food bowls.The general intel says they will hit a point in a couple of days at most they will be "living off the land" and stripping South Korea for support. "In theory" they expected them to start loosing cohesion as this goes on. It's arguable if they can actually launch an attack and more likely to stand on the defensive. YMMV

Randy

Yes but that doesn’t mean they’ll be pushovers for US and ROK forces like Saddam’s army.Just curious, doesn't the KPA suffer from logistics in longer protracted war? Especially since their fuel is limited and their soldiers much less their people aren't well fed?

Think about how outmatched the Japanese forces at Iwo Jima and Okinawa were yet they were the bloodiest battles of the Pacific War.

Last edited:

The KPA has the same amount fanaticism as the IJA. I'll acknowledge that.Yes but that doesn’t mean they’ll be pushovers for US and ROK forces like Saddam’s army.

Think about how outmatched the Japanese forces at Iwo Jima and Okinawa were yet they were the bloodiest battles of the Pacific War.

A lot of people here are overlooking the fact that war on the Korean Peninsula in the late 1990s was probably the most improbable it had been in decades. Especially for the DPRK to be the aggressors.

Fear and Loathing in the DPRK, Clingendael Institute:

An existential fear gripped Pyongyang at the end of the twentieth century. As socialist states tumbled in Europe, the DPRK retracted into an ideological spasm, unflinchingly affirming the soundness of its socialist course. It strengthened the defence of its political system under the banner of the ‘Army First’ (sŏn’gun) revolution: the DPRK’s answer to the post-Cold War era. While showing a brave face towards both domestic and international adversity, the DPRK has also shown its capability to respond in a more pragmatic manner, through engagement with the South. This resulted in two important agreements: the North–South Agreement on Reconciliation, Nonaggression and Exchanges and Cooperation (13 December 1991); and the Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula (31 December 1991).31 Although the Joint Declaration was never implemented, as a formal expression of the DPRK’s principal commitment to the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, it remains an important document. From the DPRK’s perspective, it promises the reciprocal withdrawal of the US nuclear threat. In that sense, this inter-Korean agreement is also part of an ongoing intricate diplomatic pas de deux with the United States.32 The DPRK only signed up to the agreement after the United States had made public (be it indirectly) the withdrawal of its nuclear warheads from the Korean Peninsula. That the Declaration never moved beyond the principle was partly a consequence of a conflicting dynamic that had developed between the DPRK and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).33 The IAEA’s credibility had been severely tarnished following the discovery of the extent of Iraq’s secret uranium enrichment programme in the wake of the first Gulf War (1990-1991). The IAEA sought to reassert its authority through enforcing a more intrusive inspection mechanism. The first country to be confronted with the IAEA’s new face was the DPRK, 34 following suspicions about the comprehensiveness of its initial nuclear declaration to the IAEA. The resulting stand-off was finally resolved through direct DPRK–US negotiations that resulted in the 1994 Geneva Framework Agreement, which saw the DPRK return to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and brought the existing nuclear installations under an IAEA controlled moratorium.35 It is this Framework Agreement that unravelled in autumn 2002.

The signing of the 1994 agreement came months after the death of Kim Il-Sung on 8 July 1994. That the DPRK, despite the death of its paramount leader, went through with the deal instead of retracting in self-imposed isolation was ample proof of the importance that Pyongyang attached to these first direct negotiations with the United States since the Korean War armistice negotiations in 1953. More than just material benefits, the most important outcome for the DPRK was the ultimate prospect of a normalization of relations with the United State

When George W. Bush was sworn in as the 43rd President of the United States in January 2001, the timid process of US–DPRK rapprochement that had started in the final years of the Clinton presidency ground to a halt. Although the new administration’s Secretary of State Colin Powell recognized the initial merits of Bill Clinton’s belated and tentative engagement policy with Pyongyang, all initiatives were soon put on hold pending a US–North Korea policy review.36 In effect, the United States’ North Korea policy fell victim to ideological wrangling within the Bush administration, leading to a de facto paralysis of US policy on North Korea. Overtures created by the DPRK were wilfully ignored.37 Despite the solemn declaration in the October 2000 US–DPRK Joint Communiqué affirming that the United States had no ‘hostile intent’ towards the DPRK, George Bush made disparaging remarks about Kim Jong-Il and Bush’s ‘neo-con’ entourage made public allusions to strategies for regime change.38 The culmination of this new face of US policy came in the January 2002 State of the Union address, when George W. Bush named North Korea as part of an ‘axis of evil’ and a potential target for a pre-emptive strike.39

Particularly worrisome for Pyongyang was that the Bush administration was willing to back up its words with deeds. In stark contrast to the DPRK’s improvement of relations with South Korea and even Japan – Japan’s Prime Minister Koizumi made a surprise visit to Pyongyang in September 2002 – relations with the United States deteriorated further when deadlock was succeeded by action. On 4 October 2002, Assistant US Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs James Kelly confronted his DPRK hosts with the allegation that the DPRK was in breach of the 1994 Agreed Framework by secretly developing a highly enriched uranium-based (HEU) nuclear weapons’ programme. Kang Sok-Ju, the DPRK’s foreign minister, is said to have admitted to the existence of such a programme during an angry outburst on the fringes of the formal meetings. This outburst – whether correctly understood or not – was sufficient for the United States to move forwards in dismantling the 1994 Agreed Framework, which the Republican Party had opposed from the start.40 The United States convinced KEDO (the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization) on 14 November 2002 to suspend its monthly heavy-fuel deliveries to the North.41 In response, the DPRK accused the United States of intentionally breaking the agreement. What followed was an escalation of the crisis, in which the DPRK knowingly, but in a phased manner, disengaged from the Agreed Framework. In succession, it lifted the freeze on its nuclear installations (13 December 2002); cut the IAEA seals and disabled its surveillance cameras (22 December 2002); and ordered the expulsion of all IAEA inspectors (27 December 2002). On 10 January 2003, the DPRK informed the UN Security Council of its withdrawal from the NPT on the grounds of an imminent threat to its national security. It justified this move by referring to article X (1) of the NPT.

On 4 February 2003, the DPRK announced that it had restarted its Yongbyon reactor. While there is an intriguing sequence to the escalation, with the two protagonists locked into a staring game, neither wanting to blink first, there is a core of fundamental anxiety that should not be overlooked. Under pressure from the United States, the DPRK disengaged from its earlier commitments, on the grounds that the United States was also retracting on earlier promises and reverting to an offensive posture against the DPRK. The DPRK declared that, as a sovereign state, it had the duty to do its utmost to protect its nation’s honour and dignity. This should not be discarded as mere rhetoric. It is obvious that there was growing uncertainty in Pyongyang about US intentions. Faced with both the belligerent language of the likes of Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and John Bolton, and the actions that backed up their rhetoric, the DPRK made a dash for what it considered to be the ultimate defence strategy: the acquisition of a nuclear deterrent. When on 31 May 2003 in Cracow, Poland, George Bush announced the establishment of the Proliferation Security Initiative, the DPRK responded by declaring publicly for the first time its intention of developing such a nuclear deterrent in response to US hostile pressure.

1997 in the DPRK's foreign relations was steadily working towards détente with the South, Japan, and the US. The following year, the opposition won the South Korean elections and the Sunshine Policy came into effect, further contributing to that aim. This was all thrown out the window with the election of George W. Bush and the neo-conservative and hawkish turn in Washington, but there had been steady progress in relations with the DPRK during this time and the DPRK was declaring the end of its "Arduous March" as relations with the West and the global economy opened up. I honestly don't see a war happening in 1997 given the nature of relations with the DPRK were much different than today.

Fear and Loathing in the DPRK, Clingendael Institute:

An existential fear gripped Pyongyang at the end of the twentieth century. As socialist states tumbled in Europe, the DPRK retracted into an ideological spasm, unflinchingly affirming the soundness of its socialist course. It strengthened the defence of its political system under the banner of the ‘Army First’ (sŏn’gun) revolution: the DPRK’s answer to the post-Cold War era. While showing a brave face towards both domestic and international adversity, the DPRK has also shown its capability to respond in a more pragmatic manner, through engagement with the South. This resulted in two important agreements: the North–South Agreement on Reconciliation, Nonaggression and Exchanges and Cooperation (13 December 1991); and the Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula (31 December 1991).31 Although the Joint Declaration was never implemented, as a formal expression of the DPRK’s principal commitment to the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, it remains an important document. From the DPRK’s perspective, it promises the reciprocal withdrawal of the US nuclear threat. In that sense, this inter-Korean agreement is also part of an ongoing intricate diplomatic pas de deux with the United States.32 The DPRK only signed up to the agreement after the United States had made public (be it indirectly) the withdrawal of its nuclear warheads from the Korean Peninsula. That the Declaration never moved beyond the principle was partly a consequence of a conflicting dynamic that had developed between the DPRK and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).33 The IAEA’s credibility had been severely tarnished following the discovery of the extent of Iraq’s secret uranium enrichment programme in the wake of the first Gulf War (1990-1991). The IAEA sought to reassert its authority through enforcing a more intrusive inspection mechanism. The first country to be confronted with the IAEA’s new face was the DPRK, 34 following suspicions about the comprehensiveness of its initial nuclear declaration to the IAEA. The resulting stand-off was finally resolved through direct DPRK–US negotiations that resulted in the 1994 Geneva Framework Agreement, which saw the DPRK return to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and brought the existing nuclear installations under an IAEA controlled moratorium.35 It is this Framework Agreement that unravelled in autumn 2002.

The signing of the 1994 agreement came months after the death of Kim Il-Sung on 8 July 1994. That the DPRK, despite the death of its paramount leader, went through with the deal instead of retracting in self-imposed isolation was ample proof of the importance that Pyongyang attached to these first direct negotiations with the United States since the Korean War armistice negotiations in 1953. More than just material benefits, the most important outcome for the DPRK was the ultimate prospect of a normalization of relations with the United State

When George W. Bush was sworn in as the 43rd President of the United States in January 2001, the timid process of US–DPRK rapprochement that had started in the final years of the Clinton presidency ground to a halt. Although the new administration’s Secretary of State Colin Powell recognized the initial merits of Bill Clinton’s belated and tentative engagement policy with Pyongyang, all initiatives were soon put on hold pending a US–North Korea policy review.36 In effect, the United States’ North Korea policy fell victim to ideological wrangling within the Bush administration, leading to a de facto paralysis of US policy on North Korea. Overtures created by the DPRK were wilfully ignored.37 Despite the solemn declaration in the October 2000 US–DPRK Joint Communiqué affirming that the United States had no ‘hostile intent’ towards the DPRK, George Bush made disparaging remarks about Kim Jong-Il and Bush’s ‘neo-con’ entourage made public allusions to strategies for regime change.38 The culmination of this new face of US policy came in the January 2002 State of the Union address, when George W. Bush named North Korea as part of an ‘axis of evil’ and a potential target for a pre-emptive strike.39

Particularly worrisome for Pyongyang was that the Bush administration was willing to back up its words with deeds. In stark contrast to the DPRK’s improvement of relations with South Korea and even Japan – Japan’s Prime Minister Koizumi made a surprise visit to Pyongyang in September 2002 – relations with the United States deteriorated further when deadlock was succeeded by action. On 4 October 2002, Assistant US Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs James Kelly confronted his DPRK hosts with the allegation that the DPRK was in breach of the 1994 Agreed Framework by secretly developing a highly enriched uranium-based (HEU) nuclear weapons’ programme. Kang Sok-Ju, the DPRK’s foreign minister, is said to have admitted to the existence of such a programme during an angry outburst on the fringes of the formal meetings. This outburst – whether correctly understood or not – was sufficient for the United States to move forwards in dismantling the 1994 Agreed Framework, which the Republican Party had opposed from the start.40 The United States convinced KEDO (the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization) on 14 November 2002 to suspend its monthly heavy-fuel deliveries to the North.41 In response, the DPRK accused the United States of intentionally breaking the agreement. What followed was an escalation of the crisis, in which the DPRK knowingly, but in a phased manner, disengaged from the Agreed Framework. In succession, it lifted the freeze on its nuclear installations (13 December 2002); cut the IAEA seals and disabled its surveillance cameras (22 December 2002); and ordered the expulsion of all IAEA inspectors (27 December 2002). On 10 January 2003, the DPRK informed the UN Security Council of its withdrawal from the NPT on the grounds of an imminent threat to its national security. It justified this move by referring to article X (1) of the NPT.

On 4 February 2003, the DPRK announced that it had restarted its Yongbyon reactor. While there is an intriguing sequence to the escalation, with the two protagonists locked into a staring game, neither wanting to blink first, there is a core of fundamental anxiety that should not be overlooked. Under pressure from the United States, the DPRK disengaged from its earlier commitments, on the grounds that the United States was also retracting on earlier promises and reverting to an offensive posture against the DPRK. The DPRK declared that, as a sovereign state, it had the duty to do its utmost to protect its nation’s honour and dignity. This should not be discarded as mere rhetoric. It is obvious that there was growing uncertainty in Pyongyang about US intentions. Faced with both the belligerent language of the likes of Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and John Bolton, and the actions that backed up their rhetoric, the DPRK made a dash for what it considered to be the ultimate defence strategy: the acquisition of a nuclear deterrent. When on 31 May 2003 in Cracow, Poland, George Bush announced the establishment of the Proliferation Security Initiative, the DPRK responded by declaring publicly for the first time its intention of developing such a nuclear deterrent in response to US hostile pressure.

1997 in the DPRK's foreign relations was steadily working towards détente with the South, Japan, and the US. The following year, the opposition won the South Korean elections and the Sunshine Policy came into effect, further contributing to that aim. This was all thrown out the window with the election of George W. Bush and the neo-conservative and hawkish turn in Washington, but there had been steady progress in relations with the DPRK during this time and the DPRK was declaring the end of its "Arduous March" as relations with the West and the global economy opened up. I honestly don't see a war happening in 1997 given the nature of relations with the DPRK were much different than today.

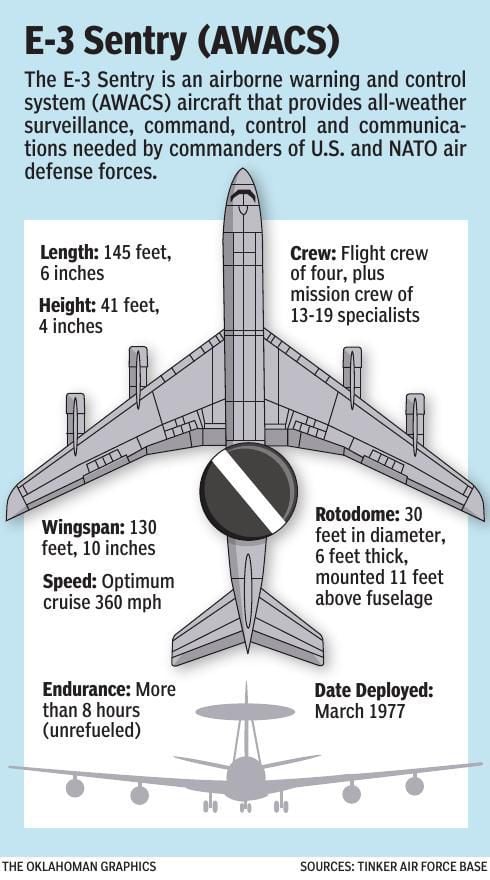

Researched a bit of the Korean People's Army Air and Anti-Air Force. So as of 1997, they operated the following SAM systems:

- S-200: Operational range of 300 km and can reach 40,000 m (130,000 ft)

- S-125 Neva/Pechora (NATO: SA-3 Goa): Operational range of 35 km and can reach 18,000 m (59,000 ft)

- 9K32 Strela-2 (NATO: SA-7 Grail): Firing range of 3,700 m (Strela-2)4,200 m (Strela-2M). Flight altitude of 50–1500 m (Strela-2) 50–2300 m (Strela-2M). This is shoulder-mounted so this can only be used against low-flying aircraft.

Share: