Given the shift away from "Date-Event" format I've been re-writing my timeline in essay form as well as making more than a couple of changes. I hope you enjoy this.

Scottish Empire

Act I, Scene I

The War of the League of Cambrai

In the aftermath of the First Italian War[1], Pope Alexander VI had moved to consolidate Papal control over central Italy by seizing the Romagna. Cesare Borgia, acting as gonfaloniere of the Papal armies, had expelled the Bentivoglio family from Bologna, which they had ruled as a fief, and was well on his way towards establishing a permanent Borgia state in the region when Alexander died on 18 August 1503. Although Cesare managed to seize the remnants of the Papal treasury for his own use, he was unable to secure Rome itself, as French and Spanish armies converged on the city in an attempt to influence the Papal conclave; the election of Pius III (who soon died, to be replaced by Julius II) stripped Cesare of his titles and relegated him to commanding a company of men-at-arms. Sensing Cesare's weakness, the dispossessed lords of the Romagna offered to submit to the Republic of Venice in exchange for aid in regaining their dominions; the Venetian Senate accepted and had taken possession of Rimini, Faenza, and a number of other cities by the end of 1503.

The following years would be marked by bloody war with alliances shifting with the winds and the nations of Europe struggling to maintain control over their respective territories. Forces under Louis XII[2] of France had managed to hold their ground in Italy and other parts of Europe and the so called “Holy League[3]” began to fracture. Henry VIII[4] took up on the chance to invade France and did and quickly came away with numerous victories. It was in August of 1513 that the French king was finally able to persuade James IV, King of Scots[5] to invade England as apart of the Auld Alliance.[6] James used his popularity with the people to rouse a massive army and crossed the border with the English hoping to force Henry to withdraw from France.

Act I, Scene II

Oh How the Fields Ran Red

The Battle of Flodden Field

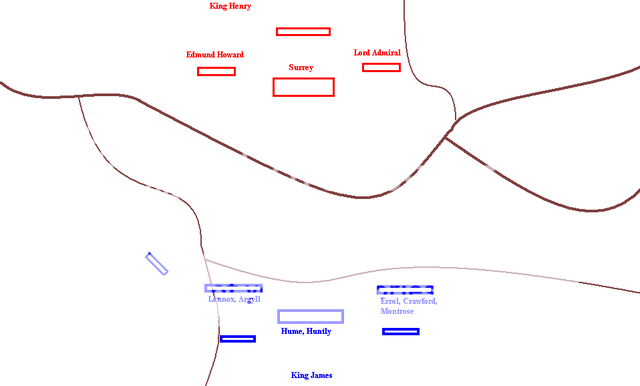

By early September the the English army under Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey[7] and Captain of the English Northern Marches had completed its muster, and the old general had approximately 26,000 men under his command, made up chiefly of archers and other infantrymen armed with the bill, the English version of the Continental halberd, an eight-foot-long weapon with a fearsome axe-like head, which could be used for cutting and slashing. All were on foot, save for the veteran campaigner Thomas, Lord Dacre, who had some 1,500 light border horsemen. Surrey was anxious that James would not be allowed to slip away, as he had during his invasion of 1497.

The English Northern Army entered the Valley of the Till and gained a clear view of the Scots a few miles away in their positions. It was now that Howard deployed another herald complaining that James had chosen a position “more like a fortress” and invited him to do battle on a level field near Milfield. James naturally refused to move away from his strong position which not only gave him the hold of the high ground, but he also could use his greater numbers to crush the English. James's reasons for accepting the challenge are unclear, when most Scottish commanders since Robert Bruce had avoided large set-piece battles with the English unless the circumstances were exceptional. The traditional explanation is that he was blinded by outmoded notions of chivalry and honor.

Surrey was now left in a dilemma, running low on supplies he would either have to abandon the field or take the steps to outflank the Scots in a risky maneuver by marching to the north and west and move between James and his lines of communication. James in fact did not abandon Flodden and remained in place for battle, a risky choice which did not sit well with his other advisors and noblemen.

Surrey began his march on the evening of the eight. His army crossed the Till in two places, the front part of the army under Surrey’s sons Edmund and Thomas Howard, crossed the Twizel Bridge, the remainder (Surrey’s, Dacre’s, and Stanley’s troops) at Milford and then marched towards Braxton Hill.

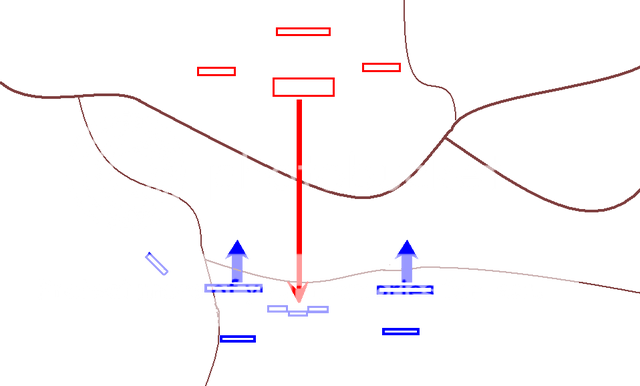

The battle began when the Scots on the high ground above the field began firing their artillery,[8] despite having heavy and more powerful guns than the English the inexperienced gunners had trouble finding the range of the English soldiers. Most of the shots rang out over the English troops or fell too short causing nothing but giving the English a nice show. The English gunners on the other hand, fired with devestating accuracy causing havoc among the Scots lines. It was then the borderers under Hume and Huntly either so confident in victory, or just tired of standing still while being shot at, charged down the slope towards Edmund Howard’s division who were standing on relativley flat ground and with level pikes the Scotsmen slammed into Howard’s division causing his front lines to crack and fracture. The fighting was hand to hand and brutal, Howard himself was unhorsed at lest twice just as some men not having the stomach for the battle deserted then and there leaving gaps in the English lines.

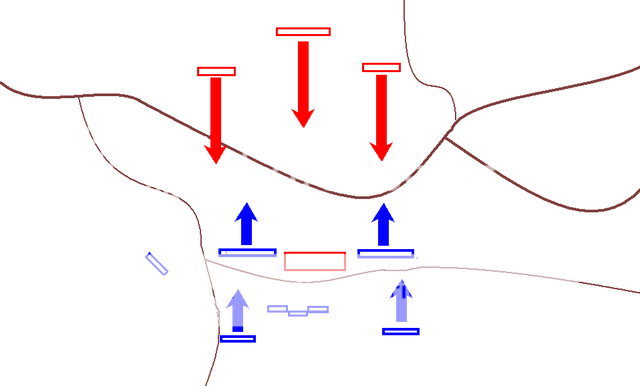

King James, saw the success and that the English cavalry was retreating in order to regroup, prepared his men to charge down the slope into the English center. Thus it would force the English to defend from two places which might cause them to divide their cavalry. It was now that he ordered his column and the column under the Earl of Bothwell to charge into the English lines. The hill side was wet and slippery and many Scotsmen threw off their shoes in order to get a better grip. All were eager for battle and some even abandoned their pikes and drew their swords. The Scotsmen crashed into the English lines with brute force and English defensive lines immediatley foundered under the pressure of the Scots, forcing a bulge in their lines as James called for more pressure on the enemy.

Meanwhile, seeing the danger of the right flank Surrey ordered another charge of the English cavalry. Despite the looks of the battle, Surrey’s men were holding their ground well and it looked as if he could afford to just bleed the Scots out. The English cavalry, under Lord Dacre charged into the forest of wooden pikes, the fighting here was likewise brutal with not just infantry but cavalry fighting hand to hand, many horsemen were dragged from their mounts and beaten to death. Lord Dacre was wounded early in the battle, however as he continued to fight the first of his cavalrymen fell back. Within minutes, Dacre himself was impaled on a Scottish pike causing even more havoc among the lines and sent his men into a frenzy. It was then that nearly the entire force of cavalry pulled back from the fighting, riding hard from the fighting nearly 1,000 horses crashed into the left side of Thomas Howard’s division. Chaos was rampant as Howard attempted to pull his men together, however almost immediatley the English lines began to roll up. Surrey in an attempt to hold his army together ordered Howard to regroup, however the damage was already done and the entire English right disintegrated before his eyes. The Earl of Surrey himself was forced to break away in order to avoid being trampled by his own men. A general retreat was soon called and as the sun began to set behind the low lying hills the fighting began to cease. King James sent another messenger stating that would not persue the English Army and instead would allow them to fall back un-harassed.

James IV, King of Scots

Act I, Scene III

A September To Die For

In the days following the monumental battle at Flodden Field, the Earl of Surrey and his army fell back to the south towards Bamburgh Castle in order to keep the Scots from moving any further into Northern England. As his army stumbled into the town, their losses became all to real, Surrey had in the course of the evening battle lost nearly 5,000 casualties including the commander of his cavalry, and his own son Edmund Howard had been severely wounded during the retreat from the field. Surrey was quick to occupy the formidable castle and quickly readied his men for a quick response by the Scots, they however had their own problems and were not pursuing the English Army.

King James IV and his large army of Scots remained at Flodden Field and the nearby town of Braxton for the following weeks attempting to lick their wounds. From the hill sides they could see their homeland, and a number deserted the army and returned to Scotland. James IV was not so quick to give up on his ambitions, his army had been victorious and the celebrations could be heard all through the nights. Despite the victory, James had still suffered and lost an unbearable 2,000 men on the field of battle. James still had confidence, the French knights under his command were still eager for battle with the English, and the biggest thing he got out of the battle was a lesson in regard to the Continental Pike[9]. If there was to be another battle, it would be on land ideal for this fearsome weapon to be employed with effectiveness. James continued to remain in Braxton to allow his men much needed rest and to take personal spoils from the English countryside.

Meanwhile in France, Henry VIII continued to gain victory after victory in his war against the French. The campaigns had been a hard one, but a war which shadows the one fought by Henry V nearly a century before. Every month more victories mounted for Henry and it looked as if it was a war England could not only win, but one which could lead to it becoming more powerful in the eyes of God. However, all this came to an end when the joyous mood in northern France was broken as news of Flodden Field arrived in front of King Henry. Understandably, the young king was not so joyous at the prospect of his Northern Army begin defeated in one of the most decisive Scottish victory in the history of the British Isles. Many in England were not only calling for action, but also an outright withdraw from France in order to focus on the war at home which before Flodden had only been a minor inconvienece to the border peoples of the north. History though, has shown us that Henry VIII was not a man who gave up easily, instead he sent word back to his wife Catherine[10] calling for her to see to the defeat of the Scots. The king had full confidence in his wife’s ability to govern the kingdom in his absence. What the king did not take into consideration was that many of the able bodied men in England were fighting alongside him in France.

As late September arrived, James was left with as many decisions as Henry VIII and Thomas Howard. Despite the fact that James IV was no military genius, he was on the other hand a very shrewd leader and he knew that a long war in England was destined to fail, Scotland did not have the resources to sustain a large offensive war and if the English did drag out the war his army would desert him. With this in mind the Scottish king ordered his army to break camp on the 19th of September and prepared them to march south. Many would argue that James had eyes on York, however it became evident as he marched southward that he intended to meet the English in battle yet again in order to bring another decisive victory that would force Henry to abandon France altogether. The march southward was a short one, however it instilled fear in the English countryside with the often yelled “The Scots are coming” filling the streets and farms of Northern England.

It was James this time who sent another herald to his enemy inviting them to do battle on the 22nd just outside Bamburgh. It would be decided whether the Earl of Surrey would accept battle or would refuse and remain in the castle. Conventional military history has taught us that forcing your enemy to lay siege is a costly move which could break your enemy’s army like a mirror, however the Earl of Surrey was just as head strong as the Scottish king and held a lot of stock in honor and chivalry. Within hours of sending the invitation James received his reply that indeed the English would meet him for battle outside Bamburgh. The English soon began withdrawing from the castle, though despite his honor and chivalry the Earl of Surrey was not oblivious to military planning and left two thousand men behind to man the castle. Even with the small number, the men would be able to hold off any attacker for a time.

The Scots entered the battleground early on the 22nd and formed his men up for battle. The English were a little later, taking their time and arriving a little after noon to find the Scots fully prepared and rigged for battle. The battle began when English artillery opened up and down the opposing lines. The artillery had its effect as the explosions created a great deal of havoc among the lines, it was not long however before Scottish artillery replied in kind. The Scots artillery was more effective than it was at Flodden Field despite there were still more than a few misses the English lines became alive with fire and explosions. As the two army’s artillery fired back and forth at each other, Surrey gave orders for his long bowmen to move forward. Perhaps because of his headstrong mind set it was now that King James ordered his infantry to charge across the field. The division under the Earl of Argyll was the first to charge across the field and brutal fighting is rampant. The battle would rage for most of the evening with no clear outcome evident until about five o’clock. As the English lines collapsed under pressure, Surrey was forced to order the retreat of his army. He hoped to return to the castle believing James would go with his last act and allow Surrey to retreat un harassed, it was not so. A reserve division under the Earl of Bothwell moved up from its position on a low hill to the rear in order to block Surrey’s line of retreat to the castle off. Surrey would be forced to move further south hoping the fortress could hold until he could gain reinforcements.

Act I, Scene IV

The Battle for Bamburgh

As early October settled over northern England, James IV knew he had to take the castle and take it quickly or be forced to spend the winter encamped in small villages and face large scale desertion. It was for this reason that James was determined to capture the castle before the month ended and the move on to Newcastle[11] where his army could remain in good condition for the rest of the winter. On the 4th of October the Scottish Army marched on the village and took strategic points at the foot of the hill atop which the castle sat. The two thousand man garrison quickly opened up on the Scots using the large number of archers in the castle to launch their attack causing havoc upon the enemy as they attempted to set up lines around the castle.

The siege was set into full swing when the Scots artillery was focused on the fortress walls, despite the formidable look of the castle the walls suffered terribly from the artillery barrage. During the War of the Roses[12] the castle had been defeated by artillery becoming the first castle to do so, and now a half century later the walls are once again being tested. The Scots laid siege to the castle for nearly a week before the east wall finally collapsed from the artillery fire, hand to hand fighting was minimal as some Scots stormed the fort and slaughtered several dozen Englishmen before the commander ordered a flag of truce lifted above Bamburgh and the battle slowly ended. James moved quickly to occupy the castle, and allowed his army two days rest before preparing to move on.

Meanwhile, in the face of the defeat at Bamburgh, Queen Catherine was attempting to find some way to cope with the crisis. Upon news of the defeat, the Queen-Consort of England deployed a message to her husband fighting in France calling upon him to “Send men to our aid, or surely see Northern England fall.” In a contemporary stand point many historians can agree the Queen’s fear was perhaps exaggerated, as while she was sending her messages of please King James was trying to form a plan to keep his army together throught the winter. Despite this, it can be said that England was in a state of fear as the barbaric Scots were now knocking at their front door and many members of Parliament were calling for the king to abandon France in order to protect the homeland. Catherine did manage to muster 5,000 men from the fields and depths of the cities to fight for St. George’s Cross, however most had no military experience and could prove unreliable in open battle. Serious questions began to grow in regard to the commander of the English Army and Catherine began to ponder removing the Earl of Surrey from his command.

Act I, Scene V

The Wrath of the King

The news of the string of defeats at home did not sit well with Henry yet again who was at the time preparing an offensive against French forces near Saint Omer. The King of England was now faced with an even bigger problem than he had before. Now faced with a Scottish Army encamped in his country, and his armies failing to keep them at bay. As well the growing opposition at home was becoming louder and the demands for him to return to England becoming more profound. By mid October the king had to make a decision whether he would remain in France throught the winter and hope for the best, or return to England and hope to defeat the Scots before they took advantage of their position. Henry eventually went with the latter choice and prepared ambassadors to seek a peace with Louis XII of France.

Henry VIII, King of England and Lord of Ireland

Footnotes:

[1] The First Italian War (1494–95), sometimes referred to as the Italian War of 1494 or Charles VIII's Italian War, was the opening phase of the Italian Wars. The war pitted Charles VIII of France, who had initial Milanese aid, against the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and an alliance of Italian powers led by Pope Alexander VI.

[2] Louis XII was the thirty-fifth king of France and the sole monarch from the Valois-Orléans branch of the House of Valois. Came to power in 1498.

[3] An alliance which pitted France, Aragon, Castile, the Papal States, and the Holy Roman Empire against the Republic of Venice. The alliance fell apart quickly.

[4] The second monarch of the Tudor Dynasty. Came to power in 1509.

[5] A Scottish monarch of the House of Stuart. Came to power in 1488.

[6] A series of treaties and agreements which formed an alliance between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of France.

[7] An English soldier and statesmen. Remembered for being defeated at the Battle of Flodden Field.

[8] The Scottish artillery used at the Battle of Flodden Field were primarily the lighter types of artillery, the larger cannons being left behind in Scotland.

[9] A large 18 foot spear, used effectively by the Swiss and French and later adapted to be used in the schiltron formation of the Scots.

[10] Catherine of Aragon was the wife of Henry VIII of England, daughter of Ferdinand II and aunt of the feared and respected Charles V.

[11] A city in Northern England along the Tyne River and only miles from the Scots border.

[12] A series of civil wars fought in the 15th Century between the Houses of York and Lancaster for control of the English crown.

Act II, Scene I

The Coming of the North

With winter fast approaching, James IV sought to move to the south and secure a viable place for his army to remain encamped for the winter. The city of Newcastle proved to be his most important target, he ordered his army to break camp and begin the march south from Bamburgh and onto Newcastle. The march south saw a degree of desertion given many wanted to be back in their own war beds in Scotland instead of the cold fields of Northern England.

As Surrey awaited the Scottish advance, his men’s condition continued to worsen. They had received no new reinforcements for the better part of a month and what men he did have in fighting condition had their moral shot down after the fall of Bamburgh. The cold months of early winter were already beginning to creep into Northern England, as well food and resources were beginning to dwindle in the fortified city and Surrey was forced to begin foraging[1] in his own country.

King James had similar problems, the cold was taking its toll on the Scottish army and with desertion rising he knew he would have to take the city or watch his army collapse. He took steps to continue feeding and clothing his army and ordered small detachments into the English countryside to pillage for resources. As in other Scottish invasions, the invading Scotsmen took pleasure in stripping the English countryside bare of all food much of it acts of revenge for similar acts[2] perpetrated by the English in Scotland. Being able to keep his army fed allowed James to march southward at his own ease and he maneuvered his army only a few miles north of Newcastle preparing them for the assault.

Meanwhile inside the city, Surrey was contemplating his own paths to take, despite the wish to continue the fight against the Scots, after two major battles Surrey came to realize that honor and chivalry could not win the war against Scotland. It was for this reason he made the decision to abandon the city of Newcastle and withdraw his army to the south bank of the River Tyne. Meeting with his lieutenants he gave forth his plan to fall back to the south where he would gain fresh supplies and wait out the winter and in the Spring continue the war. The plan was a bold one, but one with promise given that Surrey understood the need to refresh his army. He gave the order to begin withdrawing from the city as soon as scouts reported the location of the Scottish army just to the north of the city. As his men began to withdraw from the city, he ordered as much as possible to be stripped from the city in order to leave nothing of use to the Scots.

The Scottish army came within view of the city as the last defenses were being abandoned by the English. Most of the city’s populace fled with the army however a sizeable number chose to remain in the city, many of these were of Celtic decent who viewed the Scots as their liberators instead of conquerors. Surrey himself and his guard were among the last to leave the city, asuring themselves that all steps had been taken to keep the Scots from enjoying their time in Newcastle. By mid day on October 17th, 1513 the English Northern Army had abandoned the city of Newcastle and began their retreat south to York.[3]

King James entered the city of Newcastle at the head of his army, immediatley securing the castle and other key points throught and around the city. The people of the city who did not flee with the English army remained locked in their houses curiously observing the army of the northern peoples. Many thought the Scots their friends, while some worried that the Scots would immediately begin a massacre on all the peoples still in the city. James however had no time to worry about mistreating English civilians and immediately went about setting up winter quarters for his tired and hungry army. It did not take him long to discover a great amount of the city’s resources had been pulled from the city, this became a major inconvienece as now he would have to rely on the English countryside and what aid was trickling in from Scotland. Even so, James thought himself in a decent position to force a favorable peace on England. Not only had he decisively defeated the English Northern Army and captured two important fortresses but he had also dealt a major blow to English plans to win holdings[4] in France and England’s part in the War of the League of Cambrai.

Act II, Scene II

The Treaty of Orleans

With news of the fall of Newcastle an impatient and angry King Henry VIII was already drawing up plans for his return to England and the subsequent battle with his brother-in-law. Most of early winter was spent relaying messages and proposals to the Royal Court of France. The French were at the time battling Spain, the Papacy, the Holy Roman Empire, and Milan for supremacy over the Italian peninsula. For this reason France was in no position to demand the return of French land ruled by England for centuries and thus King Louis XIII agreed to hear English terms for peace. As hopes for peace grew, the two factions began to de escalate the fighting between them, King Henry even went so far as to declare a temporary peace between England and France in hopes of pushing the peace talks further.

The peace talks between England and France did succeed in sparking a degree of ill feelings between England and the other members of the League of Cambrai who felt England was abandoning the war against France. Despite this ill feelings, Henry VIII was able to keep himself on good terms with Aragon, Castile, the Papal States, and Milan.

The fighting in northern France was slowly growing to a halt as a de facto cease fire began to take effect and a permanent peace treaty being drawn up. Finally after weeks of deliberation a permanent agreement between the Kingdom of England the Kingdom of France was reached, in it Henry VIII agreed to end England’s role in the conflict against France and to withdraw to pre-war borders. The French likewise yet again recognized that Calais was and was to remain apart of the Kingdom of England. The two warring entities met in Orleans to make the final ratification of the treaty and in early November the Treaty of Orleans[5] went into effect thus ending England’s role in the War of the League of Cambrai on the Continent.

Act II, Scene III

When the Last Blade Falls

The winter was more than miserable for the Scottish Army which sat encamped on the cold ground of Northern England. Newcastle had proved a near disaster as a winter quarters for the army as with much of the city’s food stores taken and the rest burned, the Scottish soldiers had to rely on the small amount of aid trickling from Scotland and from the English countryside. Disease likewise began to ravage the large army and the desertion rate rose faster than King James could count.

Surrey’s condition was somewhat better given he and his army were warm and fed in the city of York, this did not however improve the psychological standing of the army. The men of England had been defeated twice and forced to retreat in the face of the advancing Scottish army. Surrey did however continue to remain optimistic about what Spring would bring, he understood that the Scots were near starving in their frozen city in the north and eventually they would either have to advance south or retreat back to Scotland. Even so, the thought of his defeats remained embedded in his mind and now that news of the king’s return had arrive they were even more profound. It was during mid December that a division of infantry arrived at York to reinforce him, sent by Queen Catherine.

Preparing for the onslaught that would be Spring, Surrey went about better training his rag tag army in the weeks and months he was encamped at York. There was little he could do with his army of farmers and merchants, however he harshly drilled them outside the city in an attempt to make his army into something worthy of fighting.

With the arrival of Christmas, the two armies in northern England bed down for a cold stretch to Spring. The Scots remained suffering in Newcastle with little food while the English swandered in poor moral in York. King James called for his men to remain in high hopes and delivered a rememberable speech[6] to his men on Christmas Eve. Most of his men reacted with a degree of optimism at the promise of defeating the English yet again with the coming of Spring, the people of Scotland had lived their lives learning of the many battles and wars which Scotland had lost at the hand of the English. These memories of stories long told helped motivate most of them into a wish to deliver vengeance in the memory of their forefathers.

The speech which James IV delivered in the depths of winter is credited as one of the most profound turning points in the collapse of the Scottish Army. After his memorable speech on Christmas Eve, his men found a degree of resolve to carry on.

Act II, Scene IV

We are England!

The first vestiges of Spring brought renewed hope in the safety of England. Henry VIII began to mobilize his army in Calais[7] in preparation to cross the English Channel and begin the march to defeat the Scots once and for all. Before beginning the crossing, Henry called a council of his commanders to draw up a plan for action when his army arrived in England. All agreed that the fate of England depended on the speed with which the English could march north and stop the Scots from moving any further south. Thus it was decided that no time for rest could be granted when the army landed on the east coast of England, they would begin a forced march north to York where they would reinforce Surrey’s position and take on the extra men before forcing battle on the Scots and defeating them in a decisive battle.

Henry sought to motivate his army before boarding the ships which would take them home to fight in defense of England. Every man in his army had been battle tested against some of Europe’s best soldiers, however their morale was low given all they had fought to gain had been given up in exchange for peace. Despite this, Henry still held the loyalty of these men and he reaffirmed that loyalty with perhaps his greatest speech.[8] A highly dramatized version of Henry’s speech to his men was captured in the play Henry VIII[9] by Richard Shakespear. It has been said that upon the completion of the speech his men yelled and banged their swords for hours, regardless of this tale within hours his men began boarding vessels to make the journey across the English Channel.

The crossing would not take long, and shortly the cliffs of England could be seen in the distance. The English followed the coast and moved ashore in East Anglia[10] in order to gain a quicker pace for the march north to York.

Henry VIII delivers his speech to his men at Calais.

Act II, Scene V

Let Us Ready

With the arrival of Spring, James IV found his army in nearly no condition to campaign. It had barely been able to keep itself fed and clothed during the long arduous winter months and had likewise barely kept itself unified under the weight of desertion, freezing weather, and disease. His men did however remain with him, and with the warm months of Spring at long last upon them conditions began to improve. Shipments of food and fresh clothing came in from Scotland and more of the army’s needs were brought in from the English countryside. James realized that if he was to continue his campaign in England he would have to give his army time to recuperate from the months of near starvation. Thus throughout late February and early March he spent his time bringing in food and other necessities for the continued survival of his army.

Meanwhile news spread quickly of the arrival of King Henry VIII and his army from France. People stood along the roads to see their king and their army marching to defeat the Scots and defend their beloved England. Henry himself received praise from any and everyone he encountered during his march north through England.

Henry and his army marched into the city of York by late March to cheering crowds and even happier soldiers. The Earl of Surrey was less than enthused as he remained worried at the reaction of his king at his inability to keep the Scots at bay in the north. Henry though had taken time to calm down from his ranting in France and now viewed the situation for what it was, James IV had managed to enter England and defeat the English army. Upon arriving in York, Henry met with Surrey and his other lieutenants to discuss a course of action now that the two armies had been united into one effective fighting force. All agreed that the best course of action would be to lure James into a decisive battle which would end with his defeat, after being defeat Henry would force a peace upon him and the Scots and immediatley return to France to restart the still raging war. It could be said that Henry never had any intention of honoring his treaty with the French, despite this he did know he could not do anything until the Scots were defeated.

At the same time Henry was discussing the plan for the war, James began to mobilize his now rested and well fed army. He likewise made plans on how to best execute the rest of the conflict and bring about the quickest possible peace. He would march south across the River Tyne and begin a campaign to wrest control of the vital English city of York. This plan was put into action as he and his army crossed the Tyne and began their march southward, as they did this news arrived of Henry and his army. James was shaken only slightly at the news as this had been his primary goal. However now he realized he would not be fighting the Earl of Surrey and his army of farmers but instead the King of England and his army of battle tested veterans.

[1] The act of looting perpetrated by an army in order to equip itself with food and other necessities it requires to survive. This normally also becomes an opertunity for soldiers to take personal spoils from the nation they are invading.

[2] Numerous occupations and invasions of Scotland left a deep scar on Anglo-Scottish relations given the degree of brutality used by both sides during said conflicts. Most of these are connected with the Scottish Wars of Independence and the long and brutal time spent under Edward I of England.

[3] A historic walled city in North Yorkshire, England, at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss. The city is noted for its rich history, playing an important role throughout much of its existence especially as a staging point for invasions of Scotland thus becoming a center of Scottish resentment.

[4] English holdings in France dated back centuries, stemming mainly from the Hundred Years War and likewise coupled with the English claim to be the true monarchs of France.

[5] Signed and ratified by both Henry VIII of England and Louis XIII of France effectively putting an end to the Anglo-French stage of the War of the League of Cambrai. The terms included that England would withdraw its forces back to pre-war borders and agree to end its part in the war.

[6] “And when the last arrow is loosed, when the last blade falls, and the last drop of blood strikes the ground we shall truly be freed from oppression. For you are all my sons, and the coming days will decide our fate! Now we must remember the days of long ago! Let the memories of our victories remain imbedded into your heart and mind, and let the memories of our losses burn in your stomach!

O’ but if we are to win the day then the world will remember you, and they will speak your names alongside the greatest of history! And if that day is to be our undoing, then I am content that we have fought well and hard! And I thank the Lord he has allowed me to serve beside you! So sleep my sons, and sleep well! For when the time comes we will march with the sun on our backs and the wind in our hair, and we will show them what true warriors are made of! And if they wish a war! Then we shall give them a war!

Alba Gu Brath!”

[7] A city in northern France. Captured by King Edward III of England in 1347.

[8] "Gentlemen, today we stand poised to return home and free our land of barbarous hoards from the North. Our land is ravaged and enjoyed by our most hated enemy, they seek to conquer us and make us to them as Gaul was to Caesar! But how can one conquer England when the greatest men of the world stand in her defense? O' how can any man think to defeat us on this most glorious day? We must show them our resolve, and we must show them what is this place called England!

For today there is no crown that seperates us! Let there be no division, let nothing divide our solemn voice! For whether you be a high noble or lowly farmer, today we are all Englishmen and we are all Royal! Thus now let nothing stand before our glorious triumph! Let no band of barbarian hoards ravage our land and enjoy our women, for England is above being conquered!

Charge I say! Charge once more unto breech and fill our land with their Scottish dead! Let us drive them unto the very gates of Hell and push them into the depths of Satan's lake of fire! For we surely do the Lord's work to defend our beloved England! Thus march in one step, speak as one voice, fight as one army, and when the day is done we shall take a place in history that our children will speak of for a thousand years! We are the defenders of our homes! We are the protectors of our families! We are an army of Englishmen, WE are England!”

[9] An epic play written by Richard Shakespeare becoming one of the most profound examples of the history of the British Isles. It was widely hailed for its dramatic showing of the history of both England and Scotland in the 16th Century.

[10] East Anglia is a peninsula of eastern England. It was named after one of the ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Scottish Empire

Act I, Scene I

The War of the League of Cambrai

In the aftermath of the First Italian War[1], Pope Alexander VI had moved to consolidate Papal control over central Italy by seizing the Romagna. Cesare Borgia, acting as gonfaloniere of the Papal armies, had expelled the Bentivoglio family from Bologna, which they had ruled as a fief, and was well on his way towards establishing a permanent Borgia state in the region when Alexander died on 18 August 1503. Although Cesare managed to seize the remnants of the Papal treasury for his own use, he was unable to secure Rome itself, as French and Spanish armies converged on the city in an attempt to influence the Papal conclave; the election of Pius III (who soon died, to be replaced by Julius II) stripped Cesare of his titles and relegated him to commanding a company of men-at-arms. Sensing Cesare's weakness, the dispossessed lords of the Romagna offered to submit to the Republic of Venice in exchange for aid in regaining their dominions; the Venetian Senate accepted and had taken possession of Rimini, Faenza, and a number of other cities by the end of 1503.

The following years would be marked by bloody war with alliances shifting with the winds and the nations of Europe struggling to maintain control over their respective territories. Forces under Louis XII[2] of France had managed to hold their ground in Italy and other parts of Europe and the so called “Holy League[3]” began to fracture. Henry VIII[4] took up on the chance to invade France and did and quickly came away with numerous victories. It was in August of 1513 that the French king was finally able to persuade James IV, King of Scots[5] to invade England as apart of the Auld Alliance.[6] James used his popularity with the people to rouse a massive army and crossed the border with the English hoping to force Henry to withdraw from France.

Act I, Scene II

Oh How the Fields Ran Red

The Battle of Flodden Field

By early September the the English army under Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey[7] and Captain of the English Northern Marches had completed its muster, and the old general had approximately 26,000 men under his command, made up chiefly of archers and other infantrymen armed with the bill, the English version of the Continental halberd, an eight-foot-long weapon with a fearsome axe-like head, which could be used for cutting and slashing. All were on foot, save for the veteran campaigner Thomas, Lord Dacre, who had some 1,500 light border horsemen. Surrey was anxious that James would not be allowed to slip away, as he had during his invasion of 1497.

The English Northern Army entered the Valley of the Till and gained a clear view of the Scots a few miles away in their positions. It was now that Howard deployed another herald complaining that James had chosen a position “more like a fortress” and invited him to do battle on a level field near Milfield. James naturally refused to move away from his strong position which not only gave him the hold of the high ground, but he also could use his greater numbers to crush the English. James's reasons for accepting the challenge are unclear, when most Scottish commanders since Robert Bruce had avoided large set-piece battles with the English unless the circumstances were exceptional. The traditional explanation is that he was blinded by outmoded notions of chivalry and honor.

Surrey was now left in a dilemma, running low on supplies he would either have to abandon the field or take the steps to outflank the Scots in a risky maneuver by marching to the north and west and move between James and his lines of communication. James in fact did not abandon Flodden and remained in place for battle, a risky choice which did not sit well with his other advisors and noblemen.

Surrey began his march on the evening of the eight. His army crossed the Till in two places, the front part of the army under Surrey’s sons Edmund and Thomas Howard, crossed the Twizel Bridge, the remainder (Surrey’s, Dacre’s, and Stanley’s troops) at Milford and then marched towards Braxton Hill.

The battle began when the Scots on the high ground above the field began firing their artillery,[8] despite having heavy and more powerful guns than the English the inexperienced gunners had trouble finding the range of the English soldiers. Most of the shots rang out over the English troops or fell too short causing nothing but giving the English a nice show. The English gunners on the other hand, fired with devestating accuracy causing havoc among the Scots lines. It was then the borderers under Hume and Huntly either so confident in victory, or just tired of standing still while being shot at, charged down the slope towards Edmund Howard’s division who were standing on relativley flat ground and with level pikes the Scotsmen slammed into Howard’s division causing his front lines to crack and fracture. The fighting was hand to hand and brutal, Howard himself was unhorsed at lest twice just as some men not having the stomach for the battle deserted then and there leaving gaps in the English lines.

King James, saw the success and that the English cavalry was retreating in order to regroup, prepared his men to charge down the slope into the English center. Thus it would force the English to defend from two places which might cause them to divide their cavalry. It was now that he ordered his column and the column under the Earl of Bothwell to charge into the English lines. The hill side was wet and slippery and many Scotsmen threw off their shoes in order to get a better grip. All were eager for battle and some even abandoned their pikes and drew their swords. The Scotsmen crashed into the English lines with brute force and English defensive lines immediatley foundered under the pressure of the Scots, forcing a bulge in their lines as James called for more pressure on the enemy.

Meanwhile, seeing the danger of the right flank Surrey ordered another charge of the English cavalry. Despite the looks of the battle, Surrey’s men were holding their ground well and it looked as if he could afford to just bleed the Scots out. The English cavalry, under Lord Dacre charged into the forest of wooden pikes, the fighting here was likewise brutal with not just infantry but cavalry fighting hand to hand, many horsemen were dragged from their mounts and beaten to death. Lord Dacre was wounded early in the battle, however as he continued to fight the first of his cavalrymen fell back. Within minutes, Dacre himself was impaled on a Scottish pike causing even more havoc among the lines and sent his men into a frenzy. It was then that nearly the entire force of cavalry pulled back from the fighting, riding hard from the fighting nearly 1,000 horses crashed into the left side of Thomas Howard’s division. Chaos was rampant as Howard attempted to pull his men together, however almost immediatley the English lines began to roll up. Surrey in an attempt to hold his army together ordered Howard to regroup, however the damage was already done and the entire English right disintegrated before his eyes. The Earl of Surrey himself was forced to break away in order to avoid being trampled by his own men. A general retreat was soon called and as the sun began to set behind the low lying hills the fighting began to cease. King James sent another messenger stating that would not persue the English Army and instead would allow them to fall back un-harassed.

James IV, King of Scots

Act I, Scene III

A September To Die For

In the days following the monumental battle at Flodden Field, the Earl of Surrey and his army fell back to the south towards Bamburgh Castle in order to keep the Scots from moving any further into Northern England. As his army stumbled into the town, their losses became all to real, Surrey had in the course of the evening battle lost nearly 5,000 casualties including the commander of his cavalry, and his own son Edmund Howard had been severely wounded during the retreat from the field. Surrey was quick to occupy the formidable castle and quickly readied his men for a quick response by the Scots, they however had their own problems and were not pursuing the English Army.

King James IV and his large army of Scots remained at Flodden Field and the nearby town of Braxton for the following weeks attempting to lick their wounds. From the hill sides they could see their homeland, and a number deserted the army and returned to Scotland. James IV was not so quick to give up on his ambitions, his army had been victorious and the celebrations could be heard all through the nights. Despite the victory, James had still suffered and lost an unbearable 2,000 men on the field of battle. James still had confidence, the French knights under his command were still eager for battle with the English, and the biggest thing he got out of the battle was a lesson in regard to the Continental Pike[9]. If there was to be another battle, it would be on land ideal for this fearsome weapon to be employed with effectiveness. James continued to remain in Braxton to allow his men much needed rest and to take personal spoils from the English countryside.

Meanwhile in France, Henry VIII continued to gain victory after victory in his war against the French. The campaigns had been a hard one, but a war which shadows the one fought by Henry V nearly a century before. Every month more victories mounted for Henry and it looked as if it was a war England could not only win, but one which could lead to it becoming more powerful in the eyes of God. However, all this came to an end when the joyous mood in northern France was broken as news of Flodden Field arrived in front of King Henry. Understandably, the young king was not so joyous at the prospect of his Northern Army begin defeated in one of the most decisive Scottish victory in the history of the British Isles. Many in England were not only calling for action, but also an outright withdraw from France in order to focus on the war at home which before Flodden had only been a minor inconvienece to the border peoples of the north. History though, has shown us that Henry VIII was not a man who gave up easily, instead he sent word back to his wife Catherine[10] calling for her to see to the defeat of the Scots. The king had full confidence in his wife’s ability to govern the kingdom in his absence. What the king did not take into consideration was that many of the able bodied men in England were fighting alongside him in France.

As late September arrived, James was left with as many decisions as Henry VIII and Thomas Howard. Despite the fact that James IV was no military genius, he was on the other hand a very shrewd leader and he knew that a long war in England was destined to fail, Scotland did not have the resources to sustain a large offensive war and if the English did drag out the war his army would desert him. With this in mind the Scottish king ordered his army to break camp on the 19th of September and prepared them to march south. Many would argue that James had eyes on York, however it became evident as he marched southward that he intended to meet the English in battle yet again in order to bring another decisive victory that would force Henry to abandon France altogether. The march southward was a short one, however it instilled fear in the English countryside with the often yelled “The Scots are coming” filling the streets and farms of Northern England.

It was James this time who sent another herald to his enemy inviting them to do battle on the 22nd just outside Bamburgh. It would be decided whether the Earl of Surrey would accept battle or would refuse and remain in the castle. Conventional military history has taught us that forcing your enemy to lay siege is a costly move which could break your enemy’s army like a mirror, however the Earl of Surrey was just as head strong as the Scottish king and held a lot of stock in honor and chivalry. Within hours of sending the invitation James received his reply that indeed the English would meet him for battle outside Bamburgh. The English soon began withdrawing from the castle, though despite his honor and chivalry the Earl of Surrey was not oblivious to military planning and left two thousand men behind to man the castle. Even with the small number, the men would be able to hold off any attacker for a time.

The Scots entered the battleground early on the 22nd and formed his men up for battle. The English were a little later, taking their time and arriving a little after noon to find the Scots fully prepared and rigged for battle. The battle began when English artillery opened up and down the opposing lines. The artillery had its effect as the explosions created a great deal of havoc among the lines, it was not long however before Scottish artillery replied in kind. The Scots artillery was more effective than it was at Flodden Field despite there were still more than a few misses the English lines became alive with fire and explosions. As the two army’s artillery fired back and forth at each other, Surrey gave orders for his long bowmen to move forward. Perhaps because of his headstrong mind set it was now that King James ordered his infantry to charge across the field. The division under the Earl of Argyll was the first to charge across the field and brutal fighting is rampant. The battle would rage for most of the evening with no clear outcome evident until about five o’clock. As the English lines collapsed under pressure, Surrey was forced to order the retreat of his army. He hoped to return to the castle believing James would go with his last act and allow Surrey to retreat un harassed, it was not so. A reserve division under the Earl of Bothwell moved up from its position on a low hill to the rear in order to block Surrey’s line of retreat to the castle off. Surrey would be forced to move further south hoping the fortress could hold until he could gain reinforcements.

Act I, Scene IV

The Battle for Bamburgh

As early October settled over northern England, James IV knew he had to take the castle and take it quickly or be forced to spend the winter encamped in small villages and face large scale desertion. It was for this reason that James was determined to capture the castle before the month ended and the move on to Newcastle[11] where his army could remain in good condition for the rest of the winter. On the 4th of October the Scottish Army marched on the village and took strategic points at the foot of the hill atop which the castle sat. The two thousand man garrison quickly opened up on the Scots using the large number of archers in the castle to launch their attack causing havoc upon the enemy as they attempted to set up lines around the castle.

The siege was set into full swing when the Scots artillery was focused on the fortress walls, despite the formidable look of the castle the walls suffered terribly from the artillery barrage. During the War of the Roses[12] the castle had been defeated by artillery becoming the first castle to do so, and now a half century later the walls are once again being tested. The Scots laid siege to the castle for nearly a week before the east wall finally collapsed from the artillery fire, hand to hand fighting was minimal as some Scots stormed the fort and slaughtered several dozen Englishmen before the commander ordered a flag of truce lifted above Bamburgh and the battle slowly ended. James moved quickly to occupy the castle, and allowed his army two days rest before preparing to move on.

Meanwhile, in the face of the defeat at Bamburgh, Queen Catherine was attempting to find some way to cope with the crisis. Upon news of the defeat, the Queen-Consort of England deployed a message to her husband fighting in France calling upon him to “Send men to our aid, or surely see Northern England fall.” In a contemporary stand point many historians can agree the Queen’s fear was perhaps exaggerated, as while she was sending her messages of please King James was trying to form a plan to keep his army together throught the winter. Despite this, it can be said that England was in a state of fear as the barbaric Scots were now knocking at their front door and many members of Parliament were calling for the king to abandon France in order to protect the homeland. Catherine did manage to muster 5,000 men from the fields and depths of the cities to fight for St. George’s Cross, however most had no military experience and could prove unreliable in open battle. Serious questions began to grow in regard to the commander of the English Army and Catherine began to ponder removing the Earl of Surrey from his command.

Act I, Scene V

The Wrath of the King

The news of the string of defeats at home did not sit well with Henry yet again who was at the time preparing an offensive against French forces near Saint Omer. The King of England was now faced with an even bigger problem than he had before. Now faced with a Scottish Army encamped in his country, and his armies failing to keep them at bay. As well the growing opposition at home was becoming louder and the demands for him to return to England becoming more profound. By mid October the king had to make a decision whether he would remain in France throught the winter and hope for the best, or return to England and hope to defeat the Scots before they took advantage of their position. Henry eventually went with the latter choice and prepared ambassadors to seek a peace with Louis XII of France.

Henry VIII, King of England and Lord of Ireland

Footnotes:

[1] The First Italian War (1494–95), sometimes referred to as the Italian War of 1494 or Charles VIII's Italian War, was the opening phase of the Italian Wars. The war pitted Charles VIII of France, who had initial Milanese aid, against the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and an alliance of Italian powers led by Pope Alexander VI.

[2] Louis XII was the thirty-fifth king of France and the sole monarch from the Valois-Orléans branch of the House of Valois. Came to power in 1498.

[3] An alliance which pitted France, Aragon, Castile, the Papal States, and the Holy Roman Empire against the Republic of Venice. The alliance fell apart quickly.

[4] The second monarch of the Tudor Dynasty. Came to power in 1509.

[5] A Scottish monarch of the House of Stuart. Came to power in 1488.

[6] A series of treaties and agreements which formed an alliance between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of France.

[7] An English soldier and statesmen. Remembered for being defeated at the Battle of Flodden Field.

[8] The Scottish artillery used at the Battle of Flodden Field were primarily the lighter types of artillery, the larger cannons being left behind in Scotland.

[9] A large 18 foot spear, used effectively by the Swiss and French and later adapted to be used in the schiltron formation of the Scots.

[10] Catherine of Aragon was the wife of Henry VIII of England, daughter of Ferdinand II and aunt of the feared and respected Charles V.

[11] A city in Northern England along the Tyne River and only miles from the Scots border.

[12] A series of civil wars fought in the 15th Century between the Houses of York and Lancaster for control of the English crown.

Act II, Scene I

The Coming of the North

With winter fast approaching, James IV sought to move to the south and secure a viable place for his army to remain encamped for the winter. The city of Newcastle proved to be his most important target, he ordered his army to break camp and begin the march south from Bamburgh and onto Newcastle. The march south saw a degree of desertion given many wanted to be back in their own war beds in Scotland instead of the cold fields of Northern England.

As Surrey awaited the Scottish advance, his men’s condition continued to worsen. They had received no new reinforcements for the better part of a month and what men he did have in fighting condition had their moral shot down after the fall of Bamburgh. The cold months of early winter were already beginning to creep into Northern England, as well food and resources were beginning to dwindle in the fortified city and Surrey was forced to begin foraging[1] in his own country.

King James had similar problems, the cold was taking its toll on the Scottish army and with desertion rising he knew he would have to take the city or watch his army collapse. He took steps to continue feeding and clothing his army and ordered small detachments into the English countryside to pillage for resources. As in other Scottish invasions, the invading Scotsmen took pleasure in stripping the English countryside bare of all food much of it acts of revenge for similar acts[2] perpetrated by the English in Scotland. Being able to keep his army fed allowed James to march southward at his own ease and he maneuvered his army only a few miles north of Newcastle preparing them for the assault.

Meanwhile inside the city, Surrey was contemplating his own paths to take, despite the wish to continue the fight against the Scots, after two major battles Surrey came to realize that honor and chivalry could not win the war against Scotland. It was for this reason he made the decision to abandon the city of Newcastle and withdraw his army to the south bank of the River Tyne. Meeting with his lieutenants he gave forth his plan to fall back to the south where he would gain fresh supplies and wait out the winter and in the Spring continue the war. The plan was a bold one, but one with promise given that Surrey understood the need to refresh his army. He gave the order to begin withdrawing from the city as soon as scouts reported the location of the Scottish army just to the north of the city. As his men began to withdraw from the city, he ordered as much as possible to be stripped from the city in order to leave nothing of use to the Scots.

The Scottish army came within view of the city as the last defenses were being abandoned by the English. Most of the city’s populace fled with the army however a sizeable number chose to remain in the city, many of these were of Celtic decent who viewed the Scots as their liberators instead of conquerors. Surrey himself and his guard were among the last to leave the city, asuring themselves that all steps had been taken to keep the Scots from enjoying their time in Newcastle. By mid day on October 17th, 1513 the English Northern Army had abandoned the city of Newcastle and began their retreat south to York.[3]

King James entered the city of Newcastle at the head of his army, immediatley securing the castle and other key points throught and around the city. The people of the city who did not flee with the English army remained locked in their houses curiously observing the army of the northern peoples. Many thought the Scots their friends, while some worried that the Scots would immediately begin a massacre on all the peoples still in the city. James however had no time to worry about mistreating English civilians and immediately went about setting up winter quarters for his tired and hungry army. It did not take him long to discover a great amount of the city’s resources had been pulled from the city, this became a major inconvienece as now he would have to rely on the English countryside and what aid was trickling in from Scotland. Even so, James thought himself in a decent position to force a favorable peace on England. Not only had he decisively defeated the English Northern Army and captured two important fortresses but he had also dealt a major blow to English plans to win holdings[4] in France and England’s part in the War of the League of Cambrai.

Act II, Scene II

The Treaty of Orleans

With news of the fall of Newcastle an impatient and angry King Henry VIII was already drawing up plans for his return to England and the subsequent battle with his brother-in-law. Most of early winter was spent relaying messages and proposals to the Royal Court of France. The French were at the time battling Spain, the Papacy, the Holy Roman Empire, and Milan for supremacy over the Italian peninsula. For this reason France was in no position to demand the return of French land ruled by England for centuries and thus King Louis XIII agreed to hear English terms for peace. As hopes for peace grew, the two factions began to de escalate the fighting between them, King Henry even went so far as to declare a temporary peace between England and France in hopes of pushing the peace talks further.

The peace talks between England and France did succeed in sparking a degree of ill feelings between England and the other members of the League of Cambrai who felt England was abandoning the war against France. Despite this ill feelings, Henry VIII was able to keep himself on good terms with Aragon, Castile, the Papal States, and Milan.

The fighting in northern France was slowly growing to a halt as a de facto cease fire began to take effect and a permanent peace treaty being drawn up. Finally after weeks of deliberation a permanent agreement between the Kingdom of England the Kingdom of France was reached, in it Henry VIII agreed to end England’s role in the conflict against France and to withdraw to pre-war borders. The French likewise yet again recognized that Calais was and was to remain apart of the Kingdom of England. The two warring entities met in Orleans to make the final ratification of the treaty and in early November the Treaty of Orleans[5] went into effect thus ending England’s role in the War of the League of Cambrai on the Continent.

Act II, Scene III

When the Last Blade Falls

The winter was more than miserable for the Scottish Army which sat encamped on the cold ground of Northern England. Newcastle had proved a near disaster as a winter quarters for the army as with much of the city’s food stores taken and the rest burned, the Scottish soldiers had to rely on the small amount of aid trickling from Scotland and from the English countryside. Disease likewise began to ravage the large army and the desertion rate rose faster than King James could count.

Surrey’s condition was somewhat better given he and his army were warm and fed in the city of York, this did not however improve the psychological standing of the army. The men of England had been defeated twice and forced to retreat in the face of the advancing Scottish army. Surrey did however continue to remain optimistic about what Spring would bring, he understood that the Scots were near starving in their frozen city in the north and eventually they would either have to advance south or retreat back to Scotland. Even so, the thought of his defeats remained embedded in his mind and now that news of the king’s return had arrive they were even more profound. It was during mid December that a division of infantry arrived at York to reinforce him, sent by Queen Catherine.

Preparing for the onslaught that would be Spring, Surrey went about better training his rag tag army in the weeks and months he was encamped at York. There was little he could do with his army of farmers and merchants, however he harshly drilled them outside the city in an attempt to make his army into something worthy of fighting.

With the arrival of Christmas, the two armies in northern England bed down for a cold stretch to Spring. The Scots remained suffering in Newcastle with little food while the English swandered in poor moral in York. King James called for his men to remain in high hopes and delivered a rememberable speech[6] to his men on Christmas Eve. Most of his men reacted with a degree of optimism at the promise of defeating the English yet again with the coming of Spring, the people of Scotland had lived their lives learning of the many battles and wars which Scotland had lost at the hand of the English. These memories of stories long told helped motivate most of them into a wish to deliver vengeance in the memory of their forefathers.

The speech which James IV delivered in the depths of winter is credited as one of the most profound turning points in the collapse of the Scottish Army. After his memorable speech on Christmas Eve, his men found a degree of resolve to carry on.

Act II, Scene IV

We are England!

The first vestiges of Spring brought renewed hope in the safety of England. Henry VIII began to mobilize his army in Calais[7] in preparation to cross the English Channel and begin the march to defeat the Scots once and for all. Before beginning the crossing, Henry called a council of his commanders to draw up a plan for action when his army arrived in England. All agreed that the fate of England depended on the speed with which the English could march north and stop the Scots from moving any further south. Thus it was decided that no time for rest could be granted when the army landed on the east coast of England, they would begin a forced march north to York where they would reinforce Surrey’s position and take on the extra men before forcing battle on the Scots and defeating them in a decisive battle.

Henry sought to motivate his army before boarding the ships which would take them home to fight in defense of England. Every man in his army had been battle tested against some of Europe’s best soldiers, however their morale was low given all they had fought to gain had been given up in exchange for peace. Despite this, Henry still held the loyalty of these men and he reaffirmed that loyalty with perhaps his greatest speech.[8] A highly dramatized version of Henry’s speech to his men was captured in the play Henry VIII[9] by Richard Shakespear. It has been said that upon the completion of the speech his men yelled and banged their swords for hours, regardless of this tale within hours his men began boarding vessels to make the journey across the English Channel.

The crossing would not take long, and shortly the cliffs of England could be seen in the distance. The English followed the coast and moved ashore in East Anglia[10] in order to gain a quicker pace for the march north to York.

Henry VIII delivers his speech to his men at Calais.

Act II, Scene V

Let Us Ready

With the arrival of Spring, James IV found his army in nearly no condition to campaign. It had barely been able to keep itself fed and clothed during the long arduous winter months and had likewise barely kept itself unified under the weight of desertion, freezing weather, and disease. His men did however remain with him, and with the warm months of Spring at long last upon them conditions began to improve. Shipments of food and fresh clothing came in from Scotland and more of the army’s needs were brought in from the English countryside. James realized that if he was to continue his campaign in England he would have to give his army time to recuperate from the months of near starvation. Thus throughout late February and early March he spent his time bringing in food and other necessities for the continued survival of his army.

Meanwhile news spread quickly of the arrival of King Henry VIII and his army from France. People stood along the roads to see their king and their army marching to defeat the Scots and defend their beloved England. Henry himself received praise from any and everyone he encountered during his march north through England.

Henry and his army marched into the city of York by late March to cheering crowds and even happier soldiers. The Earl of Surrey was less than enthused as he remained worried at the reaction of his king at his inability to keep the Scots at bay in the north. Henry though had taken time to calm down from his ranting in France and now viewed the situation for what it was, James IV had managed to enter England and defeat the English army. Upon arriving in York, Henry met with Surrey and his other lieutenants to discuss a course of action now that the two armies had been united into one effective fighting force. All agreed that the best course of action would be to lure James into a decisive battle which would end with his defeat, after being defeat Henry would force a peace upon him and the Scots and immediatley return to France to restart the still raging war. It could be said that Henry never had any intention of honoring his treaty with the French, despite this he did know he could not do anything until the Scots were defeated.

At the same time Henry was discussing the plan for the war, James began to mobilize his now rested and well fed army. He likewise made plans on how to best execute the rest of the conflict and bring about the quickest possible peace. He would march south across the River Tyne and begin a campaign to wrest control of the vital English city of York. This plan was put into action as he and his army crossed the Tyne and began their march southward, as they did this news arrived of Henry and his army. James was shaken only slightly at the news as this had been his primary goal. However now he realized he would not be fighting the Earl of Surrey and his army of farmers but instead the King of England and his army of battle tested veterans.

[1] The act of looting perpetrated by an army in order to equip itself with food and other necessities it requires to survive. This normally also becomes an opertunity for soldiers to take personal spoils from the nation they are invading.

[2] Numerous occupations and invasions of Scotland left a deep scar on Anglo-Scottish relations given the degree of brutality used by both sides during said conflicts. Most of these are connected with the Scottish Wars of Independence and the long and brutal time spent under Edward I of England.

[3] A historic walled city in North Yorkshire, England, at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss. The city is noted for its rich history, playing an important role throughout much of its existence especially as a staging point for invasions of Scotland thus becoming a center of Scottish resentment.

[4] English holdings in France dated back centuries, stemming mainly from the Hundred Years War and likewise coupled with the English claim to be the true monarchs of France.

[5] Signed and ratified by both Henry VIII of England and Louis XIII of France effectively putting an end to the Anglo-French stage of the War of the League of Cambrai. The terms included that England would withdraw its forces back to pre-war borders and agree to end its part in the war.

[6] “And when the last arrow is loosed, when the last blade falls, and the last drop of blood strikes the ground we shall truly be freed from oppression. For you are all my sons, and the coming days will decide our fate! Now we must remember the days of long ago! Let the memories of our victories remain imbedded into your heart and mind, and let the memories of our losses burn in your stomach!

O’ but if we are to win the day then the world will remember you, and they will speak your names alongside the greatest of history! And if that day is to be our undoing, then I am content that we have fought well and hard! And I thank the Lord he has allowed me to serve beside you! So sleep my sons, and sleep well! For when the time comes we will march with the sun on our backs and the wind in our hair, and we will show them what true warriors are made of! And if they wish a war! Then we shall give them a war!

Alba Gu Brath!”

[7] A city in northern France. Captured by King Edward III of England in 1347.

[8] "Gentlemen, today we stand poised to return home and free our land of barbarous hoards from the North. Our land is ravaged and enjoyed by our most hated enemy, they seek to conquer us and make us to them as Gaul was to Caesar! But how can one conquer England when the greatest men of the world stand in her defense? O' how can any man think to defeat us on this most glorious day? We must show them our resolve, and we must show them what is this place called England!

For today there is no crown that seperates us! Let there be no division, let nothing divide our solemn voice! For whether you be a high noble or lowly farmer, today we are all Englishmen and we are all Royal! Thus now let nothing stand before our glorious triumph! Let no band of barbarian hoards ravage our land and enjoy our women, for England is above being conquered!

Charge I say! Charge once more unto breech and fill our land with their Scottish dead! Let us drive them unto the very gates of Hell and push them into the depths of Satan's lake of fire! For we surely do the Lord's work to defend our beloved England! Thus march in one step, speak as one voice, fight as one army, and when the day is done we shall take a place in history that our children will speak of for a thousand years! We are the defenders of our homes! We are the protectors of our families! We are an army of Englishmen, WE are England!”

[9] An epic play written by Richard Shakespeare becoming one of the most profound examples of the history of the British Isles. It was widely hailed for its dramatic showing of the history of both England and Scotland in the 16th Century.

[10] East Anglia is a peninsula of eastern England. It was named after one of the ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Last edited: