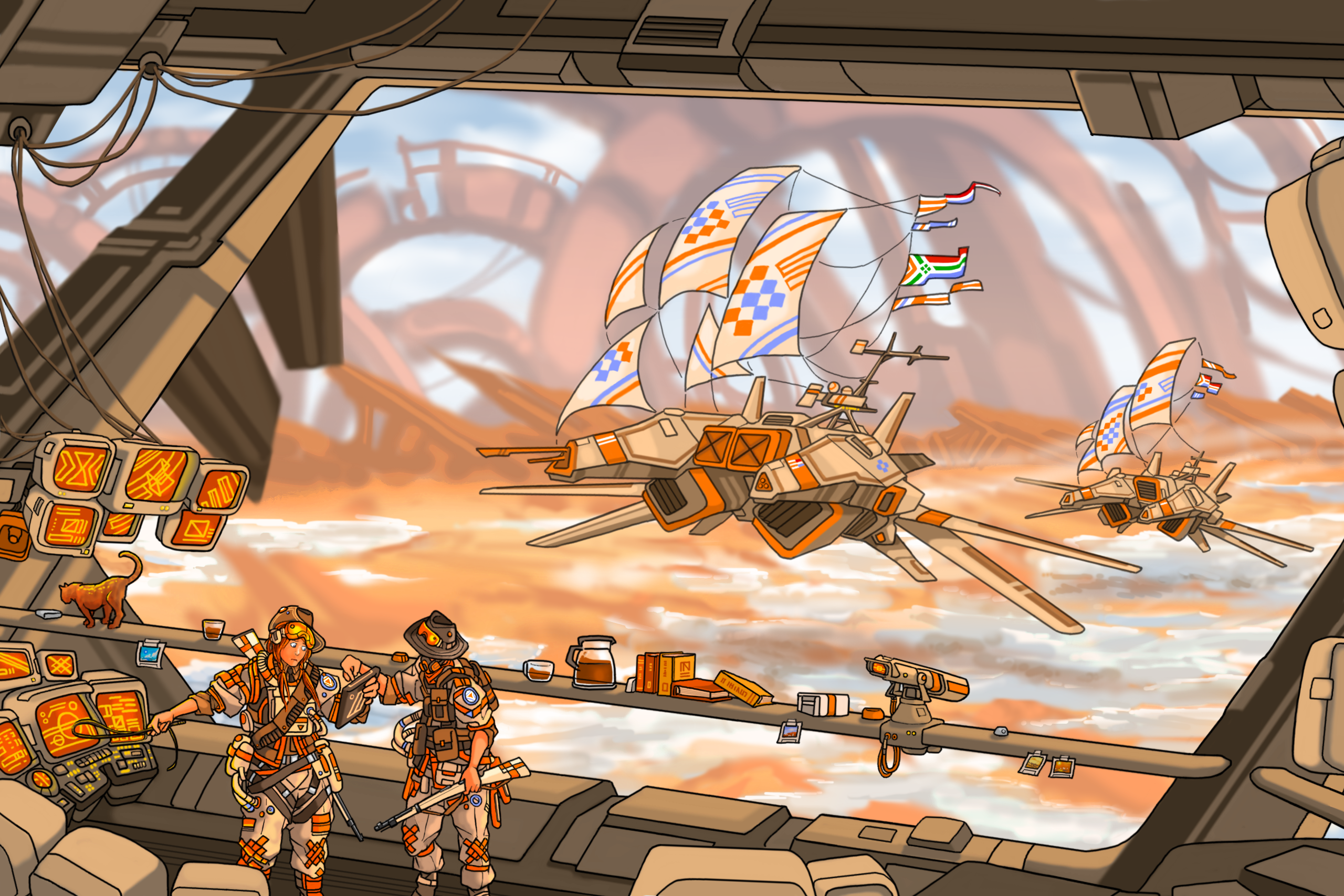

View from the bridge of the snelskip-class surface cruiser

Heidelberg Heksie. In the background, the cruisers

Valkiri and Rooi Haar Hond are visible, with all three vessels constituting the main striking element of the “Jan Compagnie”, a minor Staatsjaer sister squadron of the Transorbitaal Republiek. The squadron is transiting the Redlands Isthmus on a northwestern spur of the Elephants’ Graveyard in order to intercept an unlicensed commercial nanodust convoy registered to the SinoCorp Conglomerate. Although in recent years the Transorbitaal Republiek has considerably loosened restrictions on the sale of transit licenses to Kommersant-affiliated corporate and colonial subsidiaries wishing to send convoys along the Republiek’s proprietary Great Northern Dust Route, the alluring profitability of the highly trafficked shipping route and the steep cost of Republiek licensing fees still induce many unscrupulous traders and smugglers to attempt illegal transits, which makes the Great Northern a target rich environment for the Republiek’s Staatsjaer squadrons.

Indeed in the centuries since the Orbitaaler opening of the equatorial passages and the subsequent establishment of the global trading network of the Afrikander mercantile republics, Afrikander dominance of the most profitable long distance shipping routes across and astride both hemispheres has come under increasing threat from the rising industrial nations of the Kommersant, the Red Empire, and the Free Djong-Kok states, who would all profit enormously from even the slightest reduction of the Afrikander monopoly on long distance bulk trade. The initially overwhelming Afrikander superiority in speed and volume of traffic by means of their squadrons of surface cruiser cargo haulers has been increasingly challenged in recent decades by the vast expansion of the merchant marine fleets of their competitors in both hemispheres. Though nowhere near as efficient in fuel consumption and speed as a traditional Afrikander mercantile republic of three to five surface cruisers and a similar number of corvette escorts, a modern Kommersant commercial convoy-fleet consisting of hundreds of trade-clippers and accompanying fuel tenders, gun clipper escorts, and other auxiliary vessels can come very close to matching an Afrikander republic in terms of cargo capacity and fleet security. Red and Free Djong Kok convoy-fleets, though neither as large nor well-defended as those of the mammoth Kommersant merchant marine, are similarly able to muster hundreds of motorized cargo sailskimmers and revenue cutters to challenge the Afrikaner mercantile republics in volume if not in speed of trade.

To combat these rising threats to their various trade monopolies, the thinly stretched Afrikander mercantile republics were initially rather powerless to act. Punitive trade blockades and embargoes were enforceable only by stripping the mercantile fleets of valuable shipping tonnage and subsequent sacrifices in profits for each reduced trading voyage, while the commercial merchant convoy-fleets of competitors were nearly too numerous for the handful of surface cruisers and ossewaen to halt without provoking a full scale fleet action and potential war. Ultimately, the answer was found in the haphazard commissioning of privateers, in grudging emulation of most other seagoing states of both hemispheres.

Almost overnight, the most vulnerable Afrikander republics had suddenly given rise to ramshackle privateer fleets flying the four-colored banners of the Afrikander clans but crewed by Djong Kok pirate bands, Kommersant deserters, and Texacoran commerce raiders, the usual collection of unsavory foreigners who might be found lounging about any disreputable waterfront tavern with a revolver on his hip and a ship to his name. But unlike the privateers of other nations, those commissioned by the Afrikander mercantile republics were instructed to restrict their predations to the proprietary Afrikander trade routes, keeping them clear of trespassing competition, which was subject to seizure and conditional release on impounding of cargo, except in the rare cases of sanctioned convoys which had paid handsomely for the privilege of operating along one or another of the Afrikander trade routes. These experienced, if ill equipped privateers were at first somewhat effective in policing the Afrikander trade routes, but their efficiency was soon diminished by their innate greed and corruption. Many of the less disciplined and lawless privateers soon engaged in wholesale piracy wherever they liked under the Afrikander flags, which not only took the privateers away from their essential task of policing assigned trade routes but also caused a diplomatic uproar in the aftermath of each new outrage. Worse yet, an even greater number of unscrupulous privateers simply began taking hefty bribes from illicit, undeclared merchant convoys seeking to dodge the burgeoning system of licensing fees and cargo impounding.

Clearly changes had to be made. The first generation of foreign privateers was dismissed almost en masse, with the Afrikander republics retaining only the most reliable and effective captains and crews as auxiliaries. To fill the newly created gap in the nascent privateering fleets, the mercantile republics turned to the desperate Orbitaaler freebooters of the equatorial wastes. In the aftermath of the Great Dust War, more than a dozen of the old Orbitaaler salvaging clans which had thrown in their lot with the belligerent nanodust mining republics had seen their livelihoods utterly destroyed. Salvage was no longer as plentiful as it had once been in their forefathers’ generations, especially with the Kommersant’s consolidation of territorial gains in the temperate bands of the southern hemisphere, and many an ossewa laager had been wrecked or ruined in fleet engagements with the Kommersant’s mobile squadrons during the later years of the war.

A fortunate minority of these dispossessed Orbitaaler clans were able to fall back on existing alliances and arrangements with their relations among those Orbitaaler mining republics who had managed to retain their nanodust claims in the aftermath of the Great Dust War, or with those Orbitaaler salvaging clans still operating in the outer latitudes of the equatorial wastes, or otherwise find new places aboard the Afrikander mercantile republics. However, a large proportion of the remainder were reduced to offering their services to the surviving Orbitaaler republics in the bitter post-war pacification campaigns to clear the equatorial wastes of upstart Freeporter pirate bands, which had taken advantage of the wartime chaos to reclaim vast tracts of the Elephants’ Graveyard and subsidiary debris fields.

These anti-Freeporter pacification expeditions were hard and dangerous affairs involving both dismounted and fleet combat among the twisted wreckage and ruins of the Elephants’ Graveyard. Even when augmented by Legionaar companies and tactical officers, such post-war campaigns resulted in relatively high casualties among the dispossessed Orbitaaler clans who volunteered their rifles, their vehicles, and their lives in service of these expeditions in exchange for a pittance in compensation from the mining republics which would most greatly benefit from the neutralization of the resurgent Freeporter menace. Within a single bloody generation, the equatorial wastes had been pacified, and it appeared that there would be no further need for the hardened survivors of the bitter post-war campaigns.

It was to this class of Orbitaaler freebooters that the Afrikander republics looked for their new privateering crews. Desperate for work, experienced in the fundamentals of fleet combat against a wily foe, and unlikely to betray their own Afrikander kinsmen for the bribes of foreign smugglers and illegal traders, the Orbitaaler freebooters were rapidly brought up in droves from the equatorial wastes to man the reformed privateering fleets. Pioneering organizational work was done in this field by the newly established Afrikanderstaat, which standardized on a privateering fleet composition based on small squadrons of Orbitaaler-crewed surface cruiser interceptors augmented by larger squadrons of conventional Texacoran or Djong-Kok privateer auxiliaries. Aided by orbital surveillance, aerial drone sweeps, and autonomous listening posts, the fast interceptor squadrons were assigned the task of hunting down illegal convoy-fleets, neutralizing any armed escorts, and immobilizing the cargo haulers. Afterwards, the conventional foreign auxiliary squadrons were brought onto the scene and tasked with going from ship to ship to board and impound cargoes or assign prize crews if necessary.

Initial forays under the new doctrine were successful, and this Afrikanderstaat tactical arrangement eventually proved a winning formula and was adopted by the other Afrikander mercantile republics and in time, even by the handful of Orbitaaler republics which had laid claim to longstanding proprietary trade routes of their own. To this day, in fact, the Afrikanderstaat’s pioneering influence in the field of privateering is evident in the very name of those commissioned privateers of Afrikander or Orbitaaler origin: Staatsjaere, or State Hunters. Though a Staatsjaer may be in the employ of any Afrikander or Orbitaaler republic, the freebooter class is known by no other appellation.

However, one key element of the Afrikander privateering formula still remained to be developed before the mercantile republics were able to regain their dominance over their old trade routes and the Staatsjaere were to become the fearsome force that they are today. Initially, the Staatsjaere were given second-rate corvette-class surface cruisers with which to hunt down their prey. These stolid workhorses of the Afrikander mercantile republics, though the fastest vessels in their fleets, were too few and too poorly armed to handle the larger, well-protected convoy-fleets of the greater Kommersant and Red Djong-Kok proxies and subsidiary states. Armed with a pair of recalibrated mining lasers or, at best, a single heavily refurbished point defense particle beam or laser system salvaged from the ancient starshipwrecks of the great southern debris fields, the Afrikander corvettes simply lacked the capability to effectively engage multiple targets simultaneously or even in rapid succession. When attempting to ambush and neutralize convoy-fleets with ship counts numbering in the dozens if not the hundreds, a number of early Staatsjaer actions were characterized by the mass dispersal of illegal convoys after the initial shock of an attack wore off, with hundreds of vessels peeling off in every direction and too few Staatsjaer corvettes and auxiliaries on hand to catch all but a fraction of the total projected haul.

To remedy this tactical conundrum, a new class of surface cruiser was required. Something more numerous, and thus smaller and less costly to produce, than a corvette, with massed long range firepower superior to anything yet fielded by the Afrikander and Orbitaaler fleets. These requirements produced the snelskip, or fast ship, class of surface cruiser. Constructed from the pared down chassis of decommissioned or scrapped corvette-class cruisers, the resultant snelskip cruisers proved faster and more maneuverable than any other class of surface cruiser over any terrain, courtesy of a reduction in mass via the omission of the typical cavernous cargo hold that constitutes the bulk of most Afrikander cruisers. Where the early Staatsjaer corvettes would assist in the collection and transport of impounded cargo, the snelskip-cruisers were totally incapable of carrying more than the necessary minimum in onboard supplies and munitions, with all cargo transport duties falling on entirely on the foreign auxiliary squadrons within a privateering fleet. Massed firepower was provided in the form of forward launching bays stocked with cheaply produced guided missiles, manufactured from existing autofab blueprints for survey rockets and mining munitions. Guided missile technology was hardly a new development, but it had fallen out of favor with Afrikander, Orbitaaler, and even Legionaar fleet tacticians due to their fixation on the more elegant firepower solution provided by particle beam and laser weaponry.

Equipped with primitive logic circuits, radar range finders, and fed with basic operating parameters, barrages of 155mm guided missiles launched simultaneously by the cruisers of a Staatsjaer squadron could strike and immobilize an entire target convoy in a matter of minutes with swift and precise plunging fire before the convoy could even sound the alarm to disperse. Any escort craft would be neutralized from above by missiles armed with incendiary or armor piercing, high explosive payloads, while cargo haulers carrying valuable goods might be immobilized with missiles launching simple kinetic sabots or shrapnel canisters. Although such guided missile systems would be ineffective against the heavy ceramsteel armor and point defense systems of any capital ship or battlewagon of the main Kommersant or Red battle fleets, such valuable and easily identifiable vessels would never be detailed to illegal convoy escort duty.

Nevertheless, there is some talk of making contingency plans for the consolidation and confederation of all Staatsjaer squadrons into a Staatsleer, or State Army, in the event of another full scale fleet war between the Kommersant and some future alliance of the Afrikander and Orbitaaler republics. Certainly the privateering Staatsjaere are kept in a higher state of readiness for fleet combat than most Afrikander cruiser kapteins or Orbitaaler ossewa kommandants, even if their missile systems are no match for the reliable laser and particle beam phalanxes that are still the standard aboard many cruisers and ossewaen. And indeed, some republics have commissioned their affiliated Staatsjaer squadrons to conduct port blockades and fight fleet actions against foreign commercial rivals in the lawless colonial north, utilizing the Staatsjaere as a standing army of sorts in order to avoid having to call up their own mercantile cruiser fleets and sacrifice commercial revenue in the waging of war.

None of these broader strategic implications much concerns the Staatsjaere themselves, though, as many among them are quite content to bury themselves in the lucrative work of hunting the many illegal convoys that still seek to try their luck on the Afrikander trade routes. Indeed, for a good catch, the prize shares and goods-impound commission awarded to even the most junior Staatsjaer rookie in a three-cruiser squadron can total up to a considerable sum, even after the mercantile republic which owns the rights to the trade route takes its sizable cut. Still, the adventurous and exciting life of a Staatsjaer is not considered a desirable or permanent profession outside of the freebooting Orbitaaler class, as very few Staatsjaer cruisers are fully owned by their kapteins, being almost always financed in part by Staatsbank investments during the many lulls in the trading season. Indeed, the lucrative sale of affordable transit licenses to foreign merchants by many lesser republics has even reduced the prey for some Staatsjaer squadrons hunting among those less traveled trade routes, and such republics only retain the bare minimum of Staatsjaer cruisers to deter the odd illegal convoy from attempting a run.

On the more lucrative and consequently more competitive hunting routes, however, the golden age of the Staatsjaer is still in full swing. Among their ranks are to be found a diverse assortment of Afrikanders and Orbitaalers of all stripes and origins. Legionaar cadet tacticians looking for command experience in fleet combat, eager Orbitaaler youths excited for a few seasons of adventurous hunting on the famous trade routes of the colonial north before returning to their backwater salvage laagers or mining claims, and luckless Afrikander mercantile officers hoping for a profitable catch so they can buy back their ownership shares of their ancestral cruisers, to name just a few. Nevertheless, Orbitaaler freebooters, Vryjaers or Free Hunters as they often prefer to style themselves, still constitute a slight majority of the highly fluid Staatsjaer class, though they are no longer the dispossessed and propertyless desperadoes of their forebears’ time. Instead, most of those families and clans descended from the Orbitaaler freebooters of old have reintegrated with established Orbitaaler republics, and they merely encourage their sons and daughters to pursue commissions with Staatsjaer squadrons to earn their fortunes until such time as a command opening appears in their home republic or laager. Ideally, a returned Vryjaer brings with him substantial command experience and a sizable fortune to invest in the improvement of his ancestral republic.

Satisfaction and pride of their chosen profession as Staatsjaer, however, is hardly indicative of good relations between a Vryjaer kaptein or crewman and the wealthy Afrikander mercantile republic on whose behalf he hunts. Most Vryjaere are at least somewhat disdainful of those Afrikander mercantile republics which draw more revenue from the sale of overpriced transit licenses and seizure of impounded goods on a given trade route than the republic’s own commercial trade in goods on that same route. Indeed, many Vryjaere are acutely aware of the irony in their critical role in enforcing Afrikander commercial hegemony and trade monopoly over vast swathes of the northern hemisphere. They, whose Orbitaaler forbears were themselves descended from deep space mining technicians and long haul contractors of Boer extraction who had rebelled against an oppressive corporate conglomerate whose hapless Kaapenaar executives and local administrators had meekly joined in the Great Exodus across the stars and whose descendants are well represented among the ranks of the great Afrikander mercantile republics.

In acknowledgement of this historical irony, many a Staatsjaer cruiser which is overwhelming crewed by Vryjaer Orbitaalers defiantly flies some variant of the Vyfkleur flag, which is itself a defaced version of a hated emblem associated with the long dead ZAMKOR conglomerate which once oppressed the rebellious forbears of the Orbitaaler and Afrikander peoples. In truth, the ancient banner from which the Vyfkleur is derived was merely the national flag of the Third South African Republic, a long defunct entity to which the ZAMKOR conglomerate owed its fealty in the days before the Wars of Dissolution and subsequent Collapse. To create the Vyfkleur, the central point of the ancient banner is cut into four diamonds of equal size to represent the four ancestral tribes of the modern Orbitaaler and Afrikander peoples (ie, the Legionaar, the Kaapenaar, and the two Boer tribes).

Other notes on the depicted scene:

Most Staatsjaer bridges are cluttered with a small library of silhouette reference books and transit license records, as the high volume of both legal and illegal traffic on any given trade route makes target recognition and identification a matter of the greatest priority during the initial stages of any hunt. Though most legitimately licensed trade convoys will broadcast their registered transponder on open frequencies and halt when ordered, some fearing pirate attack or attempting to travel discreetly to beat their competition to market will not, while just as many illegal unlicensed convoys will try to mimic the transponder broadcasts of legitimately registered convoys and present cleverly falsified documents on request. Thus, visual identification of suspicious convoys and cross checking of convoy departure schedules, manifests, and other corroborating documentation is critical to ensuring that no legal convoys are accidentally targeted and no illegal convoys allowed to pass unchallenged. A Staatsjaer spends many hours studying and memorizing the silhouettes and identifying markings of those licensed foreign vessels that regularly ply his assigned trade route to ensure that there will be no false positives in identification in the heat of the moment.

The predominantly Orbitaaler origin of the majority of Staatsjaer crews is evident in the ubiquitous presence of Boer coffee and tobacco on the bridge of many a Staatsjaer cruiser. More so than the average Orbitaaler or Afrikander kaptein or command officer, a typical Staatsjaer is kept on the highest level of alert while on watch duty during a hunting cruise on a heavily trespassed trade route, and much coffee and tobacco is consumed to keep the Staatsjaer crew ready and on the bounce in the event of a combat action.

Another indication of the Staatsjaer crew's Orbitaaler origins is the wielding of a ceremonial sjambok whip by the tactical officer. Most mercantile Afrikander officers prefer to display their command status through embellishments to their clothing or headgear, or through the wearing of customized badges of rank and the like, in imitation of the military styling of the Kommersant and Texacor nations. Such influence is also evident in the gold trim on the tactical officer's slouch hat, which is an ornamentation characteristic of the modern Afrikander style. The presence of geweer rifles on the bridge is also largely an Orbitaaler practice, though Staatsjaere have considerably more reason than most Afrikander cruiser officers to be armed while on duty. The occasional unexpected point defense or boarding action during a hunt demands a state of vigilant readiness on the part of individual Staatsjaere.

Though not strictly an Orbitaaler custom, the keeping of a ship’s cat by some Staatsjaer crews is also a tradition attributed by them to the Orbitaalers’ spacefaring forebears. Like all other Afrikander and Orbitaaler cats, the feline mascot of the

Heidelberg Heksie (known affectionately to the Staatsjaer crew as Kommandantjie Jones) is, by tradition, said to be descended from two breeding pairs of Boer cats that originally accompanied the forefathers of the Orbitaaler and Afrikander peoples on the century-long Great Exodus across the stars. By the time of their arrival in the Corvus system, legend has it that there were enough descendants of the original four cats for each clan to claim its own ship’s cat when the first wave of Orbitaalers set foot on the planetary surface in the ossewa cargo lifters they had dropped from orbit. In the subsequent centuries after planetfall, the original Boer feline stock was undoubtedly diluted by the interbreeding of Orbitaaler and Afrikander cats with those animals kept by the Djong-Kok colonists of the northern hemisphere, but to this day, many Orbitaalers retain an inordinate pride in the pedigree of their ship’s cat.

Although most seafaring peoples of both hemispheres observe a bewildering array of superstitions associated with the presence, treatment, or behavior of ship’s cats, Orbitaaler crews (and by extension many Vryjaer and Staatsjaer crews) observe only one. It is considered bad luck by Orbitaalers to allow a ship’s cat to prowl the vast cargo holds, darkened maintenance corridors, munitions bays, reactor access points, and other confined interior spaces within the labyrinthine mechanical bowels of a ship or vehicle. From a pragmatic perspective, one inevitably expends hours of grief and trouble to find and retrieve an inquisitive cat which wanders into the seemingly endless maze of passageways, substations, compartments, conduits, and ducts that runs through the heart of any Orbitaaler ship or vehicle and provides an uncountable number of places in which a skittish cat may hide. The superstitious, however, insist that the uninhibited wandering of a ship’s cat into these dark places, far from the bright and clean surroundings of the ship’s bridge or living quarters, summons a sort of shadowy demon known in the Afrikander tongue as the Swartspook, or Black Ghost. The terrifyingly ravenous demon is said to silently stalk the darkened corridors and cargo holds of unlucky ships, closely shadowing the unfortunate crewman who is detailed to retrieve the wandering cat, before suddenly striking a fatal lightning blow and then vanishing with the victim into thin air. Most skeptics attribute the frightening legend of the Black Ghost to generations of exasperated Orbitaaler kapteins trying (without much success) to discourage curious Orbitaaler children from horsing around in the potentially dangerous maintenance areas aboard their vehicles and ships, to say nothing of losing the ship’s cat in those same areas. The superstitious, however, claim that the legend dates all the way back to the spacefaring days of their Boer ancestors among the distant mining stations and ore haulers of a faraway star system, where such shadowy demons supposedly did haunt lifeless planetoids and derelict spacecraft.