Chapter 1: The Fall of An Empire

Chapter 1: The Fall of An Empire

***

Chapter 8 of Last Empire of Europe: The Soviet Union by Alexei Trymoshenko

“The reporters and officials of Moscow gathered at Vnukovo airport after the end of the August Coup in the early hours of August 22 to welcome the president on his return from his Crimean nightmare saw a tired by upbeat Gorbachev descend from the steps of the plane. While Gorbachev’s family retired to a limousine arranged for them by the Russian government, the president spoke with the media. He spoke about the Crimean captivity and promised to say more about the days to come after governmental affairs were looked after. But he also gave an assessment of the new political situation and the tasks awaiting him.

Gorbachev exiting the plane after the August Coup.

“The main thing”, said Gorbachev before the cameras, “is that all we have done since 1985 has produced real results.” He thanked Boris Yeltsin personally for his stand during the coup and expressed special appreciation to the citizens of the Russian Federal Soviet Republic.

However, the next few days, Gorbachev would miss a good amount of chances to become a new kind of politician and would lose the all-important first round in his contest for power with Boris Yeltsin, the ever more powerful leader of the Russian Federation. This loss would have a profound impact on the future of the Soviet Union.

Eager to sort out the governmental mess after the August Coup, Gorbachev began to fill in the cabinet positions and started to dismiss people who were sympathetic to the coup. However, this would not last. Yeltsin decided that every ministerial position would need to be checked by him before being appointed, and he would not allow people not ratified by him to gain the positions in the cabinet. Gorbachev indebted to Yeltsin and having lost a lot of his remaining political prestige after the coup, could do nothing but remain red in humiliation and follow the orders that Yeltsin gave him, such as appointing Yeltsin’s yes-man Yevgenii Shaposhnikov as the new Minister of Defense being promoted from his previous position as the Air Marshal. Other yes-men of Yeltsin such as Vadim Bakatin etc were also carried out much to the humiliation of Gorbachev himself. Aleksander Bessmertnykh, the Foreign Minister who had not been willing to support any side during the coup was also swept away from his position on the insistence of Yeltsin and replaced by another Yeltsin ally.

Gorbachev was clearly in heavy retreat. He was confused, and his own political position undermined by accusations that he had orchestrated the coup to garner sympathy and destroy the factions of the CPSU. Gorbachev was quickly losing ground to the Russian nationalist faction led by Yeltsin. However he returned to Moscow, determined to regain his position not only as the head of state but also as the head of the party. However Gorbachev considered the breakup of the CPSU inevitable by all standards. The coup had made sure of that. However he wanted an amicable divorce, and a united leftist front against what was seemingly a nationalistic attack on the state itself. It would have given him more credence for his democratic views if elections between several left factions could be coordinated to show his commitment to democracy. Yeltsin had suspected that Gorbachev would do something like that, however while he had ordered the Central Committee of the Communist Party to be closed down in wait for Gorbachev to call a CPSU meeting, the general chaos after the coup prevented the orders from reaching the Moscow authorities, who were undecided about closing the committee building or not.

On the eve of August 22, Gorbachev called for a meeting of the highest deputies of the state party to be held on August 23 much to Yeltsin’s horror. At the same time, instigated by pro-Yeltsin forces, popular liberal democratic supporters of democratic revolution had gathered in Moscow to start demonstrations against the government and the Soviet Union. They managed to, aided by the Moscow police, who were Yeltsin allies, to tear the statue of Iron Felix, the founder of the KGB, down in Lubianka Square.

On August 23, Gorbachev and Yeltsin began to bargain for ministerial positions. Yeltsin aided by the help of his Latvian Marxist ally, Gennadii Burbulis, managed to undermine Gorbachev as Yeltsin demanded that the shredding of documents in party headquarters be stopped. Party members had been shredding documents implicating them in the coup. Shredding was indeed going on, however it was few and far between, far from the massive amount that both Burbulis and Yeltsin claimed. Nikolai Kruchina, who was the Head of the Central Committee Staff and preparing for the meeting of the party leaders that evening was assaulted near the committee building by nationalists and liberal democrats, being demanded to open the building to the rioters and the protestors to stop the shredding of documents. Kruchina, for purposes unknown to us, agreed that he would stop the shredding of documents, but he would not allow protestors inside, as it would impede the future meeting. Dissatisfied, the protestors tried to enter, however KGB reinforcements trained their machine guns at the protestors in clear warning. Many had seen the results of such in Tianmen in China, and as such were not willing to repeat such an incident. The Protestors continued to riot, but did not force their way in.

the toppling of the Felix statue in Lubianka Square.

Before leaving for the party meeting, Yeltsin asked Gorbachev for a public television address to the nation. It would be Gorbachev’s greatest blunder, yet greatest feat as well. Gorbachev agreed to the address, and on live he thanked Yeltsin and the Russian parliament for acting so decisively against the coup. He revealed that he had signed a decree elevating Alexander Rutskoi, a colonel at the time to the rank of general for his services. Yeltsin had expected Gorbachev to make a ploy about the Union Treaty and speak about it, catch him on it and discredit him on national television. Gorbachev must have caught on to this himself, because he made no mention of the union treaty. Yeltsin backtracked and asked the suspension of the activities of the Russian Communist Party, which if Gorbachev did, would destroy the central power of the Soviet Union, which despite its political liberalization, was still very much ran by the party. Gorbachev was stunned by the demand and angrily replied, losing his cool, and said, “Mr. Yeltsin, banning parties and suspending their activities was the manner of doing things in the autocratic Soviet Union of old. Both you and I have tried to move past such days in the past decade, however reviving such manner of doing things in the government would be hypocritical of both of us.” Of You was left unsaid but heard by everyone in the shooting corridor and everyone watching from their homes with their televisions. Yeltsin was for the first time caught off guard by Gorbachev, and Yeltsin amended his position and asked what would be happening with the Russian Communist Party members who had supported the coup. Gorbachev replied with the fact that a commission would survey the members and the court would prosecute them through legal and lawful manners.

Gorbachev was successful, utilizing the small amount of spine he had grown during the interview and his slightly increased presence and therefore influence to vote on a dissolution of the central frame of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, with 36% of the party voting in favor of dissolving the central framework, 31% voting against it and the remainder abstaining with their votes. Led by Rhyzov, the CPSU nonetheless, renewed their pledge to save the Soviet Union and stabilize the situation. Kruchin, was told to draft up a new framework for the party to work in a more decentralized manner and to provide a unified force against the nationalistic forces against them.

However the political damage was done. Many resented that Gorbachev had broken up the party structure and decentralized the structure of the party, and the small amount of influence he had strangled from Yeltsin continued to die out. The Soviet President’s downfall became complete on Saturday August 24. On the morning of that day he and Yeltsin attended the funeral of the three young men who had died defending the Soviet White House on the night of August 20 against the coup. Gorbachev tried to use the situation to express his gratitude to those who had defended democracy. He was also eager to show the all-Union flag, no longer being able to hide his real intent of the All-Union, awarding the title Hero of the Soviet Union posthumously to all three men. The crowd was moved that is for sure, however Yeltsin managed to finally steal Gorbachev’s thunder. The Russian Federation had no awards of its own and as a part of the USSR, devolved as it may have been, it had no authority to grant any wards. Yeltsin simply asked the mothers of the three young men in open television to forgive him for not being able to save their sons. With this comment, he had won the day.

After the funeral, Yeltsin forced Gorbachev alongside the Russian Prime Minister, Ivan Silaev to pass a number of decrees strengthening the republics, whilst at the same time, weakening central authority. With his political capital spent and in shambles, Gorbachev finally resigned as the General Secretary of the Party, citing the attitude of its leadership during the coup. This alienated the party, and Yeltsin had virtually every right to deal with the party in his own ways now that Gorbachev, his main rival was out of proper power.

The first to go was Boris Pugo, the Minister of the Interior. The man had committed suicide. A suicide note stuck to his desk wrote that “This is all a mistake. I have lived honestly all my life, and I now bear the consequences of one mistake.”

Pugo had been an honest man, and a hardworker, a rarity in the last years of the Soviet Union, and his death, his loyalties misplaced as it was during the coup, was a hefty blow. Similarly, another man who believed in what he was doing during the coup, yet morally sound, Marshal Sergei Akhromeev committed suicide as well in his office. In the letter he wrote to Gorbachev and the Supreme Soviet before killing himself he wrote, “Beginning in 1990, I was convinced, as I am convinced today, that our nation is heading towards perdition. Soon it will be dismembered. I looked for a way to say that aloud, even as I signed all the arms limitation treaties……I understand that as a Marshal of the Soviet Union I have violated my military oath and committed a grave military crime……Nothing remains for me but to take the responsibility for what I have done.” To his suicide note, the Marshal attached around 58 rubles, the money he owed to Kremlin cafeteria. Grigory Yavlinsky, the future President of the Russian Federation remembers him as ‘A misguided man, who supported the coup, however no one could fault his morals. He had fought for the Soviet Union during the Great Patriotic War, and he could not bear to see its dissolution.’

Marshal Sergei Akhromeev

Nikolai Kruchina, probably the last man who could have been able to save the Party and its apparatus, too committed suicide by jumping off an apartment when his finances became suspect in the eyes of the now Yeltsin run government. Several others in the Soviet apparatus committed suicide, or broke down, being arrested by Yeltsin. The Party with a State was falling down, Kruchina, Pugo and the Marshal were only the first unfortunate victims.

***

Chapter 18 of The Convoluted Independence of Ukraine

During the entire scene of the coup, Ukrainian democrats and nationalists had come down to Kiev to protest against the central government and many demanded independence, raising the blue and yellow standard that was so typically associated with the Ukrainian peoples. Leonid Kravchuk, the silver haired Speaker of the Ukrainian Parliament, had to stay on the defensive, as he did not wish to take any side during the coup. What happened in Moscow during the coup had caught everyone in the Ukrainian parliament and government by surprise, Kravchuck included. It presented a major challenge to the growing autonomist, regionalist and nationalist movement in Ukraine, as the coup makers made it an implicit promise that they would recentralize the government, and that meant taking away the powers of the internal republics one by one that had been gifted to them after 1985. Kravchuk had also resisted calls from the Communist Secretary in Ukraine, Stanislav Hurenko to place the western districts of Ukraine within Ruthenia and Rusyn lands under martial law, and to declare an emergency, as Kravchuk, already fighting for his political life during the coup, could not make promises that would degrade his standing any further, especially in western Ukraine, which was the highest hotbed of Ukrainian nationalism and regionalism in comparison to eastern Ukraine.

Leonid Kravchuk

Krvachuk’s stand against declaring an emergency was shared by the Ukrainian government. None of its members supported the coup, recalled the liberal deputy Prime Minister of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Serhii Komisarenko. Many in the Ukrainian presidium had openly called the coup anticonstitutional and that the Ukrainians had to take matters into their own hands. However if there was a lack of support for the coup, there was also no lack of fear. Many feared the coup would succeed, and Ukrainian autonomy which had become more than just fanciful words on a paper after 1985, would once again become fanciful words on a paper.

Meanwhile Kravchuk had conducted an impossible balancing act in Ukraine, addressing the Ukrainian Republic, calling for calm, however he refused to either support or condemn the coup. Reiterating his calls for calm he pleaded for time.

However Ukrainian nationalists were going to take advantage of the chaos in the central government to do what they wanted – independence. Led by Viacheslav Chornovil, a longtime prisoner of the Gulag and now the head of the Lviv Regional Administration in Western Ukraine, spent the days leading up to the coup in Zaporizhia conducting a political campaign as a democratic candidate against the communists in the upcoming elections. Chornovil’s first reaction to the coup was basically the same as that of Kravchuk’s; both were eager to make a deal with the military, exchanging peace on the streets for its noninterference in governmental affairs. This strategy was also adopted by key Yeltsin ally, Anatoly Sobchak, the democratically elected mayor of Leningrad. With the help of his deputy, Vladimir Putin, Sobchak made a deal with the KGB exchanging peace in Leningrad for his noninterference with whatever was going on in Moscow. But Chornovil’s reaction, dictated largely by his role as head of the regional administration in the largest center of western Ukraine, was not shared by many opposition leaders in Kyiv, some of whom called for active resistance.

On August 21, the decisive day of the coup, Kravchuk immediately did what the opposition deputies had been demanding for days: he jumped on Yeltsin’s bandwagon. He later claimed that he had kept in touch with the besieged Russian leader and his entourage throughout the coup. The Ukrainian Speaker was the first republican leader whom Yeltsin had called on the morning of August 19. Although he failed to convince Kravchuk to join forces in resisting the coup, he received assurances that Kravchuk would not recognize the Emergency Committee. Kravchuk never formally violated his promise to the Russian leader. On the last day of the coup, Yeltsin told George Bush that he believed he could trust Kravchuk.

On August 22, the day of Gorbachev’s return to Moscow, Kravchuk finally agreed to summon parliament to an emergency session. He presented his agenda for the session at the press conference he called that day to explain his vacillation during the coup. Kravchuk wanted parliament to condemn the coup, establish parliamentary control over the military, KGB, and police on Ukrainian territory, create a national guard, and withdraw from negotiations on a new union treaty. “It isn’t necessary for us to rush into signing the union treaty,” said Kravchuk to the press. “I believe that at this moment the Soviet Union needs to form a government for this transitional period, maybe a committee or council, perhaps with nine people or so, which could protect the actions of democratic institutions. All political forms must be re-evaluated. However, I do believe that we should urgently sign an economic agreement.” Kravchuk was not speaking of independence. His agenda was the complete destruction of the Union center as it had existed before the coup and its replacement by a committee of republican leaders. It was a program of confederation. Ironically for the man, Ukraine would not follow this model, however another republic within the Soviet Union would.

However the national democrats wanted more. Their parliamentary leader, Ihor Yukhnovsky demanded independence. The principal author of the draft of the declaration of independence was Levko Lukianenko, the head of the Ukrainian Republican Party, by far the best organized political force in Ukraine during that period. Lukianenko had spent more than a quarter-century in the Gulag for his dedication to Ukrainian independence. He was an embodiment of Ukraine’s sacrifice in the struggle for freedom, and the democratic deputies wanted him to be the first to read the declaration. It was only because of the commotion in the democratic ranks that the honor fell to Yavorivsky. A few weeks before the coup, during President Bush’s luncheon with Ukrainian political leaders, Lukianenko had approached him and given him a note with three questions. Two of them dealt with the Ukrainian opposition, and the third, concerning Ukrainian independence, read (in shaky English) as follows: “Now that inevitable disintegration of the Russian empire is a fact, whether the government of the USA the most powerful state in the world can help Ukraine to become a full-rightsubject of international relations?”

Despite the fact that even the American delegations told him that Ukraine had no historical, political or economic basis for full independence, Lukianenko no longer believed in dialogue. He did believe, however, that the defeat of the coup presented a huge opportunity to make a breakthrough to his goal. At a general meeting of democratic deputies on the morning of August 23, Lukianenko surprised his colleagues by proposing that the question of Ukrainian independence be placed on the agenda of the emergency session of parliament. “The moment is so unique that we should solve the fundamental problem and proclaim Ukraine an independent state,” he later recalled saying in his appeal to the deputies. “If we do not do this now, we may never do it. For this period in which the communists are at a loss is a brief period: they will soon get back on their feet, and they have a majority.” Knowing how ephemeral their real power was, the democratic deputies accepted Lukianenko’s argument and entrusted him with the task of drafting the declaration. “There are two approaches to the document that we can write,” said Lukianenko to a fellow deputy whom he had handpicked as a coauthor. “We can write it either as a long or a short document. If we write it as a long document, then it will inevitably prompt discussion; if we write a short one, then it has a chance of prompting less discussion. Let’s write the shortest possible document so that we give them as little as possible to discuss about where to put a comma or what has to be changed.” And they did just that. It was not “quite the 4th of July,” joked the acting US consul in Kyiv, John Stepanchuk, later about the brevity of the declaration of Ukrainian independence. Nevertheless, when Lukianenko presented the freshly drafted text to his colleagues in the democratic caucus, they agreed with his reasoning. With few editorial changes, the text was approved for distribution among the deputies at the opening of the emergency session.

Kievans celebrating the delcaration of independence.

However the members of the parliament were split on what grounds they would be able to declare independence. Finally they declared that a referendum would be held in Ukraine regarding independence. At 9 pm the Ukrainian parliament voted for independence. Similarly the Belarusians also voted to a hold an independence referendum, led by pro-Russian Vyacheslav Kebich.

***

Chapter 19 of The Last Empire of Europe

All was not well however. On August 28, Rutskoi flew to the Crimea to save the president of the Soviet Union, he headed south yet again, this time to save the Soviet Union itself. Promoted by Gorbachev from colonel to major general after the success of his first mission, Rutskoi was on his way to Kyiv to deal with a crisis that had erupted in Russo-Ukrainian relations after Ukraine’s declaration of independence. The plan was to keep Ukraine within the Union by raising the prospect of partitioning its territory if Ukraine insisted on independence. Reporting on this new mission of Rutskoi and his colleagues, a correspondent for the pro-Yeltsin Nezavisimaia gazeta wrote, “Today they have the opportunity to inform the Ukrainian leadership of Yeltsin’s position that, given Ukraine’s exit from membership in ‘a certain USSR,’ the article of the bilateral agreement on borders becomes invalid.” Translated into plain language, this meant that Russia was denouncing its existing treaty with Ukraine, its neighbor, and threatening Ukraine with partition of its territory. “It is expected,” continued the newspaper account, “that independence will be declared today at a session of the Supreme Soviet of the Crimea.” The independence of the Crimea, an autonomous republic within Ukraine, could set off a process of partition that might lead to a violent confrontation between the two largest Soviet republics.

This was a position that the Russians did not want to take however would if they were forced. However the Crimean Parliament voted independently of the Ukrainian Parliament on August 29, 1991 to declare independence from Ukraine when the news of the Ukrainian independence became known. Led by Yury Meshkov and Nikolai Bagrov, the Crimean Parliament had decided to split off from Ukraine, which it deemed to have acted without consulting its autonomous government, and as such the actions of Kiev in the eyes of the Crimean government was illegal and anti-constitutional.

Aided by Sobchak, Rutskoi came to Kiev where he pointed out that Ukraine and Russia were one, and independence was not an option. Yeltsin had been backed to an impossible corridor. He now had to take up the mantle of being where Gorbachev had been a few days prior, to try and save the union. After the meeting with the democratic deputies, the Russian representatives and Soviet parliamentarians sat down with the official Ukrainian delegation, led by Leonid Kravchuk. Their meeting would last long into the night. From time to time the participants would come out to tell the crowd of people around the parliament building how the negotiations were going and try to calm them down. Sobchak’s attempts to appeal to the people over the heads of their unyielding leaders produced disastrous results. When he told the crowds, “It is important for us to be together,” they responded by chanting, “No!” “Shame!” “Ukraine without Moscow!” After midnight, when Kravchuk and Rutskoi finally called a press conference to report on their deliberations, the results favored the Ukrainian leadership. The two countries agreed to create joint structures to manage the transition and work on economic agreements. However the Russians also forced the Ukrainians to accept the Crimean declaration of independence, with Sobchak severely criticizing Ukrainian hypocrisy, stating that if Ukraine deserves independence then so did the Crimeans.

The outcome of the late-night deliberations in Kyiv that disappointed Stankevich encouraged Nursultan Nazarbayev, who was upset about the Russian takeover of the Union government and wanted to take control of Soviet armed forces in his republic. That day the Kazakh leader fired off a telegram to Yeltsin requesting that Rutskoi’s delegation visit Kazakhstan. It read, “Given that so far the press has carried no clearly expressed renunciation on Russia’s part of territorial claims on contiguous republics, social protest is growing in Kazakhstan, with unforeseeable consequences. This may force the republic to adopt measures analogous to those of Ukraine.” The threat to follow the Ukrainian example and declare outright independence, voiced by the leader of another nuclear republic, worked. Rutskoi, Stankevich, and Sobchak had their plane refueled and flew east instead of returning to Moscow. In Almaty, the capital of Kazakhstan, they signed a declaration analogous to the one negotiated in Kyiv. At his press conference with Nazarbayev, Rutskoi assured journalists that there were no territorial problems between Russia and Kazakhstan.

The setback in the Russian offensive against the increasingly obstinate Republican leaders and the confusion in Yeltsin’s ranks came at a time when Yeltsin himself felt completely exhausted, as was often the case after periods of extreme stress and feverish activity. Even before the crisis over the recognition of Soviet-era borders between republics, he announced to his aides that he was leaving Moscow for a two-week vacation. However before he do so, the Soviet hardliners struck one final time, and a communist hardliner killed Yeltsin when he came onto Red Square assassinating the man with a bomb blast that killed Yeltsin and injured several of his guards. The teenager who had thrown the bomb was shot down by bodyguards. In order to stop the escalation of the crisis from having an adverse effect anymore, Rutskoi was quickly elevated to the post of President of Russia, whilst Sobchak was made Vice-President. The situation was turning dangerous.

Alesandr Rutskoi, the successor of Yeltsin.

The growing crisis in relations between the Russian leadership and the republics allowed Gorbachev and his advisers, who seemed to have been swept from the scene only a few days earlier, to attempt a political comeback. Gorbachev’s return to center stage in Soviet politics began at a session of the Soviet parliament on August 28, the day Yeltsin was assassinated and the Rutskoi delegation flew to Kyiv. That day, for the first time since the coup, he found himself under attack for being subservient to Yeltsin and the Russian leadership because he supported the appointment of Yeltsin’s Prime Minister, Ivan Silaev, as head of the all-Union government. Gorbachev’s economic adviser Vadim Medvedev noted in his diary entry for the Autust 28, “The greatest passions are swirling around the creation of Silaev’s committee. People are saying that because of that committee, Union agencies are being supplanted by Russian ones. The president is being accused of acting at the dictate of the Russians.”

Ivan Silaev came to Gorbachev’s rescue, explaining that the republics would be invited to join his committee. That explanation did not sit well with many deputies, whom Gorbachev was now asking to rubber-stamp the liquidation of the cabinet, a body they had created less than a year earlier by amending the existing constitution. Gorbachev maneuvered this way and that but eventually allowed himself his first critical remarks about the now late Russian president and his actions since the coup. He said that once the coup was over, neither the Russian president nor the Russian parliament or government had the right to violate the constitution by claiming the prerogatives of the central government. Specifically at issue was the Russian attempt to take over the Soviet central bank in the chaos that followed the defeat of the coup. Gorbachev’s advisers protested. Later that day, the Russian parliament signed a decree suspending the takeover. Gorbachev and his circle were glad to claim their first victory over their Russian nemesis.

The next major victory for Gorbachev came on September 2, the opening day of the Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR, the Soviet super parliament that had the authority to change the constitution. The meeting began with Nursultan Nazarbayev reading a “Statement of the President of the USSR and the Supreme Leaders of the Republics.” It became known as 10 + 1, with 10 standing for the number of republics that subscribed to the statement and 1 for the center, represented by Gorbachev. A few days earlier Moscow newspapers had been full of articles claiming that Russia, and not the Union center, should be the 1 in the formula 9 + 1 or 10 + 1, but few Congress deputies were open to that idea. Nazarbayev’s statement brought the center back into the equation and put Gorbachev back in the game. That was the Soviet president’s main achievement.

The statement itself was the product of a compromise that reduced the actual importance of the center in all-Union affairs to a degree unimaginable before the coup. Produced at a meeting between Gorbachev and the leaders of the republics the previous evening, it reflected the new political reality—the growing power of RFSR and of the republican leaders in all-Union affairs. Leonid Kravchuk came to Moscow to say that Ukraine was implementing its declaration of independence, but before it was confirmed by referendum, he was prepared to take part in negotiations on the union treaty—just in case the declaration was not approved. Earlier he had informed Rutskoi, who was insisting on a federal structure for the Union, that the only structure acceptable to Ukraine was confederal. Nazarbayev, asserting that Ukraine’s declaration of independence had rendered the old federal Union obsolete, also threw his support behind the idea of confederation. It envisioned the Soviet Union not as a state in its own right but as a coalition of states that would create joint bodies for the conduct of foreign and military policy.

With the leaders of the two largest non-Russian republics presenting a united front, Gorbachev and Rutskoi had little choice but to give in to their demand. The Nazarbayev statement, prepared and signed by Gorbachev, Rutskoi, and other leaders of the Soviet republics, called for a new union constitution and proposed a set of measures for the so-called transitional period. They included the replacement of the Supreme Soviet and the Congress of People’s Deputies with a Constitutional Assembly composed of representatives of the republican parliaments; the creation of a State Council, the new executive body, consisting of the Union president and the leaders of the republics; and the formation of an Economic Committee made up of representatives of the republics, to replace not only the now defunct cabinet but also the controversial Silaev committee. In addition, Nazarbayev proposed that a new union treaty be signed and comprehensive economic and security agreements be concluded among the republics to guarantee the rights and freedoms of their citizens. The republics declared their intention to join the United Nations. Appearances to the contrary, Nazarbayev’s statement turned out to be a blueprint for the takeover of the center not by one republic, as Yeltsin had attempted, but by all of them. Like Yeltsin’s takeover bid before he was killed, it was directed against the existing constitution, which was declared irrelevant. To the surprise of the delegates, the declaration demanded that the Congress of People’s Deputies endorse this assault on the constitution and then dissolve itself. In their memoirs, both Gorbachev and Rutskoi refer very favorably to the Nazarbayev statement and defend its constitutionality. At the time, they also did their best to have the Congress of People’s Deputies approve the document and dissolve itself.

But after days of debate, Gorbachev and the leaders of the republics finally bullied the Congress of People’s Deputies into submission. According to Rutskoi, “Gorbachev always had trouble restraining himself when people said such nasty things around him, and when they finally drove him to the wall, he went to the podium and threatened that if the Congress didn’t dissolve itself, it would be disbanded. That cooled the ire of some of the speakers, and the proposal for the council of heads of states went through without a hitch.” The Congress thus approved the Nazarbayev memorandum and dissolved itself, but not before getting a concession of sorts: while the superparliament would be gone, the Supreme Soviet, or regular USSR parliament, which had no right to amend the constitution, would stay in place. Gorbachev later expressed satisfaction with that decision. After all, it left him with one more Union institution to rely on in his battles with the republican leaders.

The Congress completed its work on September 5. The next day Gorbachev convened the first meeting of the State Council, consisting of him and the republican leaders. “In the new reality,” remembered Yavlinsky, “Gorbachev was left with only one role: the unifier of the republics that were scattering.” One way or another, Gorbachev was back, performing a clearly diminished but still significant role that satisfied both the Russians and the leaders of the non-Russian republics for the time being. In late August one of those leaders, the Speaker of the Armenian parliament, Levon Ter-Petrosian, had explained the nature of the new arrangement in an interview with the Moscow weekly Argumenty i fakty: “If Rutskoi allows the reanimation of the center, then Gorbachev has a chance to stay. But for now Gorbachev is necessary as a stabilizing factor.”

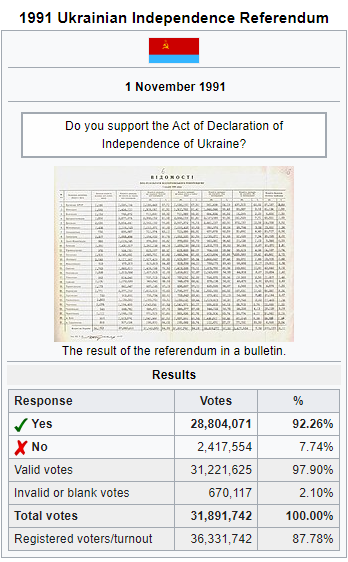

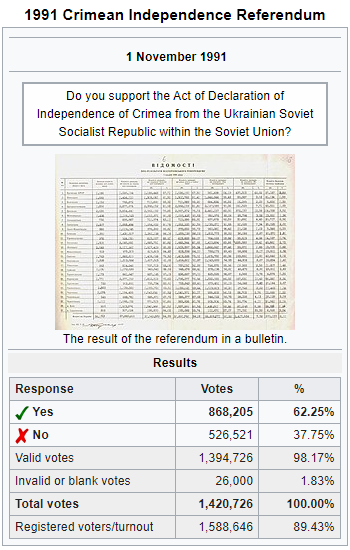

For the next month campaigning went on, as three referendums which would decide the future of the Soviet Union were to take place. The Belarusian Independence Referendum, the Ukrainian Independence Referendum and the Crimean Independence and Re-Admission Referendum. It was both a sober and happy day. The Ukrainians voted overwhelmingly to become independent, whilst Belarus and Crimea voted to stay. Despite the victories in Belarus and Crimea, Rutskoi and Gorbachev had to bow down to the inevitable. Gorbachev told Rutskoi that he would resign after the hypothetical Commonwealth of Independent States was inaugurated by ratification and signing.

On 8 November 1991, the 10 republics of the Soviet Union signed the Minsk Accords in Minsk. The negotiations were haggling and tiresome, however the basic terms of the accords came to be as:-

The Russian flag being raised in the Kremlin on November 8, 1991, the date of the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union had ceased to exist, but the Union of Russia had gained its independence with Aleksandr Rutskoi as its President. The Last Empire of Europe had fallen.

***

***

Chapter 8 of Last Empire of Europe: The Soviet Union by Alexei Trymoshenko

“The reporters and officials of Moscow gathered at Vnukovo airport after the end of the August Coup in the early hours of August 22 to welcome the president on his return from his Crimean nightmare saw a tired by upbeat Gorbachev descend from the steps of the plane. While Gorbachev’s family retired to a limousine arranged for them by the Russian government, the president spoke with the media. He spoke about the Crimean captivity and promised to say more about the days to come after governmental affairs were looked after. But he also gave an assessment of the new political situation and the tasks awaiting him.

Gorbachev exiting the plane after the August Coup.

“The main thing”, said Gorbachev before the cameras, “is that all we have done since 1985 has produced real results.” He thanked Boris Yeltsin personally for his stand during the coup and expressed special appreciation to the citizens of the Russian Federal Soviet Republic.

However, the next few days, Gorbachev would miss a good amount of chances to become a new kind of politician and would lose the all-important first round in his contest for power with Boris Yeltsin, the ever more powerful leader of the Russian Federation. This loss would have a profound impact on the future of the Soviet Union.

Eager to sort out the governmental mess after the August Coup, Gorbachev began to fill in the cabinet positions and started to dismiss people who were sympathetic to the coup. However, this would not last. Yeltsin decided that every ministerial position would need to be checked by him before being appointed, and he would not allow people not ratified by him to gain the positions in the cabinet. Gorbachev indebted to Yeltsin and having lost a lot of his remaining political prestige after the coup, could do nothing but remain red in humiliation and follow the orders that Yeltsin gave him, such as appointing Yeltsin’s yes-man Yevgenii Shaposhnikov as the new Minister of Defense being promoted from his previous position as the Air Marshal. Other yes-men of Yeltsin such as Vadim Bakatin etc were also carried out much to the humiliation of Gorbachev himself. Aleksander Bessmertnykh, the Foreign Minister who had not been willing to support any side during the coup was also swept away from his position on the insistence of Yeltsin and replaced by another Yeltsin ally.

Gorbachev was clearly in heavy retreat. He was confused, and his own political position undermined by accusations that he had orchestrated the coup to garner sympathy and destroy the factions of the CPSU. Gorbachev was quickly losing ground to the Russian nationalist faction led by Yeltsin. However he returned to Moscow, determined to regain his position not only as the head of state but also as the head of the party. However Gorbachev considered the breakup of the CPSU inevitable by all standards. The coup had made sure of that. However he wanted an amicable divorce, and a united leftist front against what was seemingly a nationalistic attack on the state itself. It would have given him more credence for his democratic views if elections between several left factions could be coordinated to show his commitment to democracy. Yeltsin had suspected that Gorbachev would do something like that, however while he had ordered the Central Committee of the Communist Party to be closed down in wait for Gorbachev to call a CPSU meeting, the general chaos after the coup prevented the orders from reaching the Moscow authorities, who were undecided about closing the committee building or not.

On the eve of August 22, Gorbachev called for a meeting of the highest deputies of the state party to be held on August 23 much to Yeltsin’s horror. At the same time, instigated by pro-Yeltsin forces, popular liberal democratic supporters of democratic revolution had gathered in Moscow to start demonstrations against the government and the Soviet Union. They managed to, aided by the Moscow police, who were Yeltsin allies, to tear the statue of Iron Felix, the founder of the KGB, down in Lubianka Square.

On August 23, Gorbachev and Yeltsin began to bargain for ministerial positions. Yeltsin aided by the help of his Latvian Marxist ally, Gennadii Burbulis, managed to undermine Gorbachev as Yeltsin demanded that the shredding of documents in party headquarters be stopped. Party members had been shredding documents implicating them in the coup. Shredding was indeed going on, however it was few and far between, far from the massive amount that both Burbulis and Yeltsin claimed. Nikolai Kruchina, who was the Head of the Central Committee Staff and preparing for the meeting of the party leaders that evening was assaulted near the committee building by nationalists and liberal democrats, being demanded to open the building to the rioters and the protestors to stop the shredding of documents. Kruchina, for purposes unknown to us, agreed that he would stop the shredding of documents, but he would not allow protestors inside, as it would impede the future meeting. Dissatisfied, the protestors tried to enter, however KGB reinforcements trained their machine guns at the protestors in clear warning. Many had seen the results of such in Tianmen in China, and as such were not willing to repeat such an incident. The Protestors continued to riot, but did not force their way in.

the toppling of the Felix statue in Lubianka Square.

Before leaving for the party meeting, Yeltsin asked Gorbachev for a public television address to the nation. It would be Gorbachev’s greatest blunder, yet greatest feat as well. Gorbachev agreed to the address, and on live he thanked Yeltsin and the Russian parliament for acting so decisively against the coup. He revealed that he had signed a decree elevating Alexander Rutskoi, a colonel at the time to the rank of general for his services. Yeltsin had expected Gorbachev to make a ploy about the Union Treaty and speak about it, catch him on it and discredit him on national television. Gorbachev must have caught on to this himself, because he made no mention of the union treaty. Yeltsin backtracked and asked the suspension of the activities of the Russian Communist Party, which if Gorbachev did, would destroy the central power of the Soviet Union, which despite its political liberalization, was still very much ran by the party. Gorbachev was stunned by the demand and angrily replied, losing his cool, and said, “Mr. Yeltsin, banning parties and suspending their activities was the manner of doing things in the autocratic Soviet Union of old. Both you and I have tried to move past such days in the past decade, however reviving such manner of doing things in the government would be hypocritical of both of us.” Of You was left unsaid but heard by everyone in the shooting corridor and everyone watching from their homes with their televisions. Yeltsin was for the first time caught off guard by Gorbachev, and Yeltsin amended his position and asked what would be happening with the Russian Communist Party members who had supported the coup. Gorbachev replied with the fact that a commission would survey the members and the court would prosecute them through legal and lawful manners.

Gorbachev was successful, utilizing the small amount of spine he had grown during the interview and his slightly increased presence and therefore influence to vote on a dissolution of the central frame of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, with 36% of the party voting in favor of dissolving the central framework, 31% voting against it and the remainder abstaining with their votes. Led by Rhyzov, the CPSU nonetheless, renewed their pledge to save the Soviet Union and stabilize the situation. Kruchin, was told to draft up a new framework for the party to work in a more decentralized manner and to provide a unified force against the nationalistic forces against them.

However the political damage was done. Many resented that Gorbachev had broken up the party structure and decentralized the structure of the party, and the small amount of influence he had strangled from Yeltsin continued to die out. The Soviet President’s downfall became complete on Saturday August 24. On the morning of that day he and Yeltsin attended the funeral of the three young men who had died defending the Soviet White House on the night of August 20 against the coup. Gorbachev tried to use the situation to express his gratitude to those who had defended democracy. He was also eager to show the all-Union flag, no longer being able to hide his real intent of the All-Union, awarding the title Hero of the Soviet Union posthumously to all three men. The crowd was moved that is for sure, however Yeltsin managed to finally steal Gorbachev’s thunder. The Russian Federation had no awards of its own and as a part of the USSR, devolved as it may have been, it had no authority to grant any wards. Yeltsin simply asked the mothers of the three young men in open television to forgive him for not being able to save their sons. With this comment, he had won the day.

After the funeral, Yeltsin forced Gorbachev alongside the Russian Prime Minister, Ivan Silaev to pass a number of decrees strengthening the republics, whilst at the same time, weakening central authority. With his political capital spent and in shambles, Gorbachev finally resigned as the General Secretary of the Party, citing the attitude of its leadership during the coup. This alienated the party, and Yeltsin had virtually every right to deal with the party in his own ways now that Gorbachev, his main rival was out of proper power.

The first to go was Boris Pugo, the Minister of the Interior. The man had committed suicide. A suicide note stuck to his desk wrote that “This is all a mistake. I have lived honestly all my life, and I now bear the consequences of one mistake.”

Pugo had been an honest man, and a hardworker, a rarity in the last years of the Soviet Union, and his death, his loyalties misplaced as it was during the coup, was a hefty blow. Similarly, another man who believed in what he was doing during the coup, yet morally sound, Marshal Sergei Akhromeev committed suicide as well in his office. In the letter he wrote to Gorbachev and the Supreme Soviet before killing himself he wrote, “Beginning in 1990, I was convinced, as I am convinced today, that our nation is heading towards perdition. Soon it will be dismembered. I looked for a way to say that aloud, even as I signed all the arms limitation treaties……I understand that as a Marshal of the Soviet Union I have violated my military oath and committed a grave military crime……Nothing remains for me but to take the responsibility for what I have done.” To his suicide note, the Marshal attached around 58 rubles, the money he owed to Kremlin cafeteria. Grigory Yavlinsky, the future President of the Russian Federation remembers him as ‘A misguided man, who supported the coup, however no one could fault his morals. He had fought for the Soviet Union during the Great Patriotic War, and he could not bear to see its dissolution.’

Marshal Sergei Akhromeev

Nikolai Kruchina, probably the last man who could have been able to save the Party and its apparatus, too committed suicide by jumping off an apartment when his finances became suspect in the eyes of the now Yeltsin run government. Several others in the Soviet apparatus committed suicide, or broke down, being arrested by Yeltsin. The Party with a State was falling down, Kruchina, Pugo and the Marshal were only the first unfortunate victims.

***

Chapter 18 of The Convoluted Independence of Ukraine

During the entire scene of the coup, Ukrainian democrats and nationalists had come down to Kiev to protest against the central government and many demanded independence, raising the blue and yellow standard that was so typically associated with the Ukrainian peoples. Leonid Kravchuk, the silver haired Speaker of the Ukrainian Parliament, had to stay on the defensive, as he did not wish to take any side during the coup. What happened in Moscow during the coup had caught everyone in the Ukrainian parliament and government by surprise, Kravchuck included. It presented a major challenge to the growing autonomist, regionalist and nationalist movement in Ukraine, as the coup makers made it an implicit promise that they would recentralize the government, and that meant taking away the powers of the internal republics one by one that had been gifted to them after 1985. Kravchuk had also resisted calls from the Communist Secretary in Ukraine, Stanislav Hurenko to place the western districts of Ukraine within Ruthenia and Rusyn lands under martial law, and to declare an emergency, as Kravchuk, already fighting for his political life during the coup, could not make promises that would degrade his standing any further, especially in western Ukraine, which was the highest hotbed of Ukrainian nationalism and regionalism in comparison to eastern Ukraine.

Leonid Kravchuk

Krvachuk’s stand against declaring an emergency was shared by the Ukrainian government. None of its members supported the coup, recalled the liberal deputy Prime Minister of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Serhii Komisarenko. Many in the Ukrainian presidium had openly called the coup anticonstitutional and that the Ukrainians had to take matters into their own hands. However if there was a lack of support for the coup, there was also no lack of fear. Many feared the coup would succeed, and Ukrainian autonomy which had become more than just fanciful words on a paper after 1985, would once again become fanciful words on a paper.

Meanwhile Kravchuk had conducted an impossible balancing act in Ukraine, addressing the Ukrainian Republic, calling for calm, however he refused to either support or condemn the coup. Reiterating his calls for calm he pleaded for time.

However Ukrainian nationalists were going to take advantage of the chaos in the central government to do what they wanted – independence. Led by Viacheslav Chornovil, a longtime prisoner of the Gulag and now the head of the Lviv Regional Administration in Western Ukraine, spent the days leading up to the coup in Zaporizhia conducting a political campaign as a democratic candidate against the communists in the upcoming elections. Chornovil’s first reaction to the coup was basically the same as that of Kravchuk’s; both were eager to make a deal with the military, exchanging peace on the streets for its noninterference in governmental affairs. This strategy was also adopted by key Yeltsin ally, Anatoly Sobchak, the democratically elected mayor of Leningrad. With the help of his deputy, Vladimir Putin, Sobchak made a deal with the KGB exchanging peace in Leningrad for his noninterference with whatever was going on in Moscow. But Chornovil’s reaction, dictated largely by his role as head of the regional administration in the largest center of western Ukraine, was not shared by many opposition leaders in Kyiv, some of whom called for active resistance.

On August 21, the decisive day of the coup, Kravchuk immediately did what the opposition deputies had been demanding for days: he jumped on Yeltsin’s bandwagon. He later claimed that he had kept in touch with the besieged Russian leader and his entourage throughout the coup. The Ukrainian Speaker was the first republican leader whom Yeltsin had called on the morning of August 19. Although he failed to convince Kravchuk to join forces in resisting the coup, he received assurances that Kravchuk would not recognize the Emergency Committee. Kravchuk never formally violated his promise to the Russian leader. On the last day of the coup, Yeltsin told George Bush that he believed he could trust Kravchuk.

On August 22, the day of Gorbachev’s return to Moscow, Kravchuk finally agreed to summon parliament to an emergency session. He presented his agenda for the session at the press conference he called that day to explain his vacillation during the coup. Kravchuk wanted parliament to condemn the coup, establish parliamentary control over the military, KGB, and police on Ukrainian territory, create a national guard, and withdraw from negotiations on a new union treaty. “It isn’t necessary for us to rush into signing the union treaty,” said Kravchuk to the press. “I believe that at this moment the Soviet Union needs to form a government for this transitional period, maybe a committee or council, perhaps with nine people or so, which could protect the actions of democratic institutions. All political forms must be re-evaluated. However, I do believe that we should urgently sign an economic agreement.” Kravchuk was not speaking of independence. His agenda was the complete destruction of the Union center as it had existed before the coup and its replacement by a committee of republican leaders. It was a program of confederation. Ironically for the man, Ukraine would not follow this model, however another republic within the Soviet Union would.

However the national democrats wanted more. Their parliamentary leader, Ihor Yukhnovsky demanded independence. The principal author of the draft of the declaration of independence was Levko Lukianenko, the head of the Ukrainian Republican Party, by far the best organized political force in Ukraine during that period. Lukianenko had spent more than a quarter-century in the Gulag for his dedication to Ukrainian independence. He was an embodiment of Ukraine’s sacrifice in the struggle for freedom, and the democratic deputies wanted him to be the first to read the declaration. It was only because of the commotion in the democratic ranks that the honor fell to Yavorivsky. A few weeks before the coup, during President Bush’s luncheon with Ukrainian political leaders, Lukianenko had approached him and given him a note with three questions. Two of them dealt with the Ukrainian opposition, and the third, concerning Ukrainian independence, read (in shaky English) as follows: “Now that inevitable disintegration of the Russian empire is a fact, whether the government of the USA the most powerful state in the world can help Ukraine to become a full-rightsubject of international relations?”

Despite the fact that even the American delegations told him that Ukraine had no historical, political or economic basis for full independence, Lukianenko no longer believed in dialogue. He did believe, however, that the defeat of the coup presented a huge opportunity to make a breakthrough to his goal. At a general meeting of democratic deputies on the morning of August 23, Lukianenko surprised his colleagues by proposing that the question of Ukrainian independence be placed on the agenda of the emergency session of parliament. “The moment is so unique that we should solve the fundamental problem and proclaim Ukraine an independent state,” he later recalled saying in his appeal to the deputies. “If we do not do this now, we may never do it. For this period in which the communists are at a loss is a brief period: they will soon get back on their feet, and they have a majority.” Knowing how ephemeral their real power was, the democratic deputies accepted Lukianenko’s argument and entrusted him with the task of drafting the declaration. “There are two approaches to the document that we can write,” said Lukianenko to a fellow deputy whom he had handpicked as a coauthor. “We can write it either as a long or a short document. If we write it as a long document, then it will inevitably prompt discussion; if we write a short one, then it has a chance of prompting less discussion. Let’s write the shortest possible document so that we give them as little as possible to discuss about where to put a comma or what has to be changed.” And they did just that. It was not “quite the 4th of July,” joked the acting US consul in Kyiv, John Stepanchuk, later about the brevity of the declaration of Ukrainian independence. Nevertheless, when Lukianenko presented the freshly drafted text to his colleagues in the democratic caucus, they agreed with his reasoning. With few editorial changes, the text was approved for distribution among the deputies at the opening of the emergency session.

Kievans celebrating the delcaration of independence.

However the members of the parliament were split on what grounds they would be able to declare independence. Finally they declared that a referendum would be held in Ukraine regarding independence. At 9 pm the Ukrainian parliament voted for independence. Similarly the Belarusians also voted to a hold an independence referendum, led by pro-Russian Vyacheslav Kebich.

***

Chapter 19 of The Last Empire of Europe

All was not well however. On August 28, Rutskoi flew to the Crimea to save the president of the Soviet Union, he headed south yet again, this time to save the Soviet Union itself. Promoted by Gorbachev from colonel to major general after the success of his first mission, Rutskoi was on his way to Kyiv to deal with a crisis that had erupted in Russo-Ukrainian relations after Ukraine’s declaration of independence. The plan was to keep Ukraine within the Union by raising the prospect of partitioning its territory if Ukraine insisted on independence. Reporting on this new mission of Rutskoi and his colleagues, a correspondent for the pro-Yeltsin Nezavisimaia gazeta wrote, “Today they have the opportunity to inform the Ukrainian leadership of Yeltsin’s position that, given Ukraine’s exit from membership in ‘a certain USSR,’ the article of the bilateral agreement on borders becomes invalid.” Translated into plain language, this meant that Russia was denouncing its existing treaty with Ukraine, its neighbor, and threatening Ukraine with partition of its territory. “It is expected,” continued the newspaper account, “that independence will be declared today at a session of the Supreme Soviet of the Crimea.” The independence of the Crimea, an autonomous republic within Ukraine, could set off a process of partition that might lead to a violent confrontation between the two largest Soviet republics.

This was a position that the Russians did not want to take however would if they were forced. However the Crimean Parliament voted independently of the Ukrainian Parliament on August 29, 1991 to declare independence from Ukraine when the news of the Ukrainian independence became known. Led by Yury Meshkov and Nikolai Bagrov, the Crimean Parliament had decided to split off from Ukraine, which it deemed to have acted without consulting its autonomous government, and as such the actions of Kiev in the eyes of the Crimean government was illegal and anti-constitutional.

Aided by Sobchak, Rutskoi came to Kiev where he pointed out that Ukraine and Russia were one, and independence was not an option. Yeltsin had been backed to an impossible corridor. He now had to take up the mantle of being where Gorbachev had been a few days prior, to try and save the union. After the meeting with the democratic deputies, the Russian representatives and Soviet parliamentarians sat down with the official Ukrainian delegation, led by Leonid Kravchuk. Their meeting would last long into the night. From time to time the participants would come out to tell the crowd of people around the parliament building how the negotiations were going and try to calm them down. Sobchak’s attempts to appeal to the people over the heads of their unyielding leaders produced disastrous results. When he told the crowds, “It is important for us to be together,” they responded by chanting, “No!” “Shame!” “Ukraine without Moscow!” After midnight, when Kravchuk and Rutskoi finally called a press conference to report on their deliberations, the results favored the Ukrainian leadership. The two countries agreed to create joint structures to manage the transition and work on economic agreements. However the Russians also forced the Ukrainians to accept the Crimean declaration of independence, with Sobchak severely criticizing Ukrainian hypocrisy, stating that if Ukraine deserves independence then so did the Crimeans.

The outcome of the late-night deliberations in Kyiv that disappointed Stankevich encouraged Nursultan Nazarbayev, who was upset about the Russian takeover of the Union government and wanted to take control of Soviet armed forces in his republic. That day the Kazakh leader fired off a telegram to Yeltsin requesting that Rutskoi’s delegation visit Kazakhstan. It read, “Given that so far the press has carried no clearly expressed renunciation on Russia’s part of territorial claims on contiguous republics, social protest is growing in Kazakhstan, with unforeseeable consequences. This may force the republic to adopt measures analogous to those of Ukraine.” The threat to follow the Ukrainian example and declare outright independence, voiced by the leader of another nuclear republic, worked. Rutskoi, Stankevich, and Sobchak had their plane refueled and flew east instead of returning to Moscow. In Almaty, the capital of Kazakhstan, they signed a declaration analogous to the one negotiated in Kyiv. At his press conference with Nazarbayev, Rutskoi assured journalists that there were no territorial problems between Russia and Kazakhstan.

The setback in the Russian offensive against the increasingly obstinate Republican leaders and the confusion in Yeltsin’s ranks came at a time when Yeltsin himself felt completely exhausted, as was often the case after periods of extreme stress and feverish activity. Even before the crisis over the recognition of Soviet-era borders between republics, he announced to his aides that he was leaving Moscow for a two-week vacation. However before he do so, the Soviet hardliners struck one final time, and a communist hardliner killed Yeltsin when he came onto Red Square assassinating the man with a bomb blast that killed Yeltsin and injured several of his guards. The teenager who had thrown the bomb was shot down by bodyguards. In order to stop the escalation of the crisis from having an adverse effect anymore, Rutskoi was quickly elevated to the post of President of Russia, whilst Sobchak was made Vice-President. The situation was turning dangerous.

Alesandr Rutskoi, the successor of Yeltsin.

The growing crisis in relations between the Russian leadership and the republics allowed Gorbachev and his advisers, who seemed to have been swept from the scene only a few days earlier, to attempt a political comeback. Gorbachev’s return to center stage in Soviet politics began at a session of the Soviet parliament on August 28, the day Yeltsin was assassinated and the Rutskoi delegation flew to Kyiv. That day, for the first time since the coup, he found himself under attack for being subservient to Yeltsin and the Russian leadership because he supported the appointment of Yeltsin’s Prime Minister, Ivan Silaev, as head of the all-Union government. Gorbachev’s economic adviser Vadim Medvedev noted in his diary entry for the Autust 28, “The greatest passions are swirling around the creation of Silaev’s committee. People are saying that because of that committee, Union agencies are being supplanted by Russian ones. The president is being accused of acting at the dictate of the Russians.”

Ivan Silaev came to Gorbachev’s rescue, explaining that the republics would be invited to join his committee. That explanation did not sit well with many deputies, whom Gorbachev was now asking to rubber-stamp the liquidation of the cabinet, a body they had created less than a year earlier by amending the existing constitution. Gorbachev maneuvered this way and that but eventually allowed himself his first critical remarks about the now late Russian president and his actions since the coup. He said that once the coup was over, neither the Russian president nor the Russian parliament or government had the right to violate the constitution by claiming the prerogatives of the central government. Specifically at issue was the Russian attempt to take over the Soviet central bank in the chaos that followed the defeat of the coup. Gorbachev’s advisers protested. Later that day, the Russian parliament signed a decree suspending the takeover. Gorbachev and his circle were glad to claim their first victory over their Russian nemesis.

The next major victory for Gorbachev came on September 2, the opening day of the Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR, the Soviet super parliament that had the authority to change the constitution. The meeting began with Nursultan Nazarbayev reading a “Statement of the President of the USSR and the Supreme Leaders of the Republics.” It became known as 10 + 1, with 10 standing for the number of republics that subscribed to the statement and 1 for the center, represented by Gorbachev. A few days earlier Moscow newspapers had been full of articles claiming that Russia, and not the Union center, should be the 1 in the formula 9 + 1 or 10 + 1, but few Congress deputies were open to that idea. Nazarbayev’s statement brought the center back into the equation and put Gorbachev back in the game. That was the Soviet president’s main achievement.

The statement itself was the product of a compromise that reduced the actual importance of the center in all-Union affairs to a degree unimaginable before the coup. Produced at a meeting between Gorbachev and the leaders of the republics the previous evening, it reflected the new political reality—the growing power of RFSR and of the republican leaders in all-Union affairs. Leonid Kravchuk came to Moscow to say that Ukraine was implementing its declaration of independence, but before it was confirmed by referendum, he was prepared to take part in negotiations on the union treaty—just in case the declaration was not approved. Earlier he had informed Rutskoi, who was insisting on a federal structure for the Union, that the only structure acceptable to Ukraine was confederal. Nazarbayev, asserting that Ukraine’s declaration of independence had rendered the old federal Union obsolete, also threw his support behind the idea of confederation. It envisioned the Soviet Union not as a state in its own right but as a coalition of states that would create joint bodies for the conduct of foreign and military policy.

With the leaders of the two largest non-Russian republics presenting a united front, Gorbachev and Rutskoi had little choice but to give in to their demand. The Nazarbayev statement, prepared and signed by Gorbachev, Rutskoi, and other leaders of the Soviet republics, called for a new union constitution and proposed a set of measures for the so-called transitional period. They included the replacement of the Supreme Soviet and the Congress of People’s Deputies with a Constitutional Assembly composed of representatives of the republican parliaments; the creation of a State Council, the new executive body, consisting of the Union president and the leaders of the republics; and the formation of an Economic Committee made up of representatives of the republics, to replace not only the now defunct cabinet but also the controversial Silaev committee. In addition, Nazarbayev proposed that a new union treaty be signed and comprehensive economic and security agreements be concluded among the republics to guarantee the rights and freedoms of their citizens. The republics declared their intention to join the United Nations. Appearances to the contrary, Nazarbayev’s statement turned out to be a blueprint for the takeover of the center not by one republic, as Yeltsin had attempted, but by all of them. Like Yeltsin’s takeover bid before he was killed, it was directed against the existing constitution, which was declared irrelevant. To the surprise of the delegates, the declaration demanded that the Congress of People’s Deputies endorse this assault on the constitution and then dissolve itself. In their memoirs, both Gorbachev and Rutskoi refer very favorably to the Nazarbayev statement and defend its constitutionality. At the time, they also did their best to have the Congress of People’s Deputies approve the document and dissolve itself.

But after days of debate, Gorbachev and the leaders of the republics finally bullied the Congress of People’s Deputies into submission. According to Rutskoi, “Gorbachev always had trouble restraining himself when people said such nasty things around him, and when they finally drove him to the wall, he went to the podium and threatened that if the Congress didn’t dissolve itself, it would be disbanded. That cooled the ire of some of the speakers, and the proposal for the council of heads of states went through without a hitch.” The Congress thus approved the Nazarbayev memorandum and dissolved itself, but not before getting a concession of sorts: while the superparliament would be gone, the Supreme Soviet, or regular USSR parliament, which had no right to amend the constitution, would stay in place. Gorbachev later expressed satisfaction with that decision. After all, it left him with one more Union institution to rely on in his battles with the republican leaders.

The Congress completed its work on September 5. The next day Gorbachev convened the first meeting of the State Council, consisting of him and the republican leaders. “In the new reality,” remembered Yavlinsky, “Gorbachev was left with only one role: the unifier of the republics that were scattering.” One way or another, Gorbachev was back, performing a clearly diminished but still significant role that satisfied both the Russians and the leaders of the non-Russian republics for the time being. In late August one of those leaders, the Speaker of the Armenian parliament, Levon Ter-Petrosian, had explained the nature of the new arrangement in an interview with the Moscow weekly Argumenty i fakty: “If Rutskoi allows the reanimation of the center, then Gorbachev has a chance to stay. But for now Gorbachev is necessary as a stabilizing factor.”

For the next month campaigning went on, as three referendums which would decide the future of the Soviet Union were to take place. The Belarusian Independence Referendum, the Ukrainian Independence Referendum and the Crimean Independence and Re-Admission Referendum. It was both a sober and happy day. The Ukrainians voted overwhelmingly to become independent, whilst Belarus and Crimea voted to stay. Despite the victories in Belarus and Crimea, Rutskoi and Gorbachev had to bow down to the inevitable. Gorbachev told Rutskoi that he would resign after the hypothetical Commonwealth of Independent States was inaugurated by ratification and signing.

On 8 November 1991, the 10 republics of the Soviet Union signed the Minsk Accords in Minsk. The negotiations were haggling and tiresome, however the basic terms of the accords came to be as:-

- The Independence of the Republic of Ukraine, Republic of Kazakhstan, Republic of Kyrgyzstan, Republic of Tajikistan, Republic of Turkmenistan, Republic of Uzbekistan, Republic of Azerbaijan and Republic of Armenia to be signed and recognized.

- The Union of Russia to be recognized as the legal successor to the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic.

- Byelorussia and Crimea to join the Union of Russia on the basis of a confederal union.

- The declaration of the ceasing of the existence of the Soviet Union and the Commonwealth of Independent States in its place.

- A conference regarding the armed forces to take place on a later date in a new conference.

The Russian flag being raised in the Kremlin on November 8, 1991, the date of the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union had ceased to exist, but the Union of Russia had gained its independence with Aleksandr Rutskoi as its President. The Last Empire of Europe had fallen.

***