You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Rightly Guided: Zaid ibn Haritha and his Rashidun Caliphate

- Thread starter GoulashComrade

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 26 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

A Bit of a Timeskip - The Ascension of Caliph Maxentius "To Jerusalem! To Damascus! To Rome!" Part I - The Final Battle in Iraq, Trouble in Madinah, and the Beginning of Ghazwah As-Sham "¡Marchamos con nuestros hermanos!"/"We march with our brothers" - A War Song of Khalid's Christian Mujahideen (by Halocon) Info Post 7 - The Possible Development of Jewish Leadership in the Caliphate (by Jonathan Edelstein) Quiz on the Caliphate! Quiz on the Caliphate - Answers! "To Kisra and Beyond!": How the Arabs ran the Iranians out of Iran - Part I "To Jerusalem, To Damascus, To Rome!" - Part II

Commander of the Faithful - Abu Bakr's Caliphate in the Ridda Wars

Commander of the Faithful

“I have been given authority over you, though I am not the best of you. If I do well, help me; and if I do wrong, set me right. Sincere regard for truth is loyalty and disregard for truth is treachery. The weak amongst you shall be strong with me until I have secured his rights, if God wills; and the strong amongst you shall be weak with me until I have wrested from him the rights of others, if God wills. Obey me so long as I obey God and His Messenger. And if I disobey God and His Messenger, then I have no right to your obedience.”

--- from the inaugural speech of Caliph Abu Bakr

“By the One who holds my soul in his right hand, even if you had every horseman in the world in your army and I had a lone blind man on a donkey in mine, I would never trade Muhammad the Blessed for Musaylimah the Liar!”

--- Commander Khalid ibn al Walid’s response to Musaylimah’s offer of co-rulership in return for laying down his arms

Excerpt from “Introduction” and other sections (Makhzum, Hasan. "Muhammad’s Shadow: Abu Bakr and his War to Unite Arabia", Al-Hullaim, 1998)

“In modern days, historians tend to look upon Abu Bakr's reign as a ‘caretaker caliphate’ of sorts. According to this view, he served admirably in his role, but was only important in providing some of the groundwork for the titanic campaigns of his illustrious successors. The praises and honors of him during his lifetime were mostly a result of hagiography, say these academics, influenced by his status as Muhammad’s right hand man. This opinion suffers from two crucial flaws that stem from a misreading of the early Muslim mindset, common amongst both Western and Islamic traditional scholars today. When recounting the greatest endeavor that they ever embarked on for the tabi’un writers that followed them, members of the Companion generation almost universally recalled the compilation of the first full manuscript of the Qur’an under Abu Bakr. The conquests were glorious, yes, but the Companions were a people who had witnessed the Prophet’s Message firsthand and possessed the kind of zeal that only comes with being converted by a religion's founder personally: Abu Bakr’s compiling of the Mus’haf was actually equivalent to Umar’s expansions in their eyes.

The other issue is that the previously described narrative ignores how close the Caliphate came to total collapse during the Ridda Wars period: at the time of his ascension to the Caliphate, the wave of rebellions following the death of the Prophet Muhammad had left the Muslims in direct control of only about 20% of Arabia's territory. Although large sections of the rank-and-file tribesmen stayed loyal to Abu Bakr and Islam despite the apostasy of their tribal leaders, it looked as if the Peninsula was heading back to the pre-Muhammad days of fractured tribalism. To the Muslims, while the conquests of the great old empires were the basis of an empire, the Ridda Wars were about nothing less than the very survival of "the Ummah for all tribes" that Muhammad dreamt of. The armies of Abu Bakr showed nothing but contempt for the apostates and their idea that the shahadah they proclaimed was only binding to Muhammad. The Companions held that the profession of faith bound one to the religion not the man, seeing the rebel’s claims as nothing more than excuses to shatter the legacy of the Prophet. Even worse in the eyes of the Muslims, some of the rebel chieftains like Musaylimah [1], Tulayha and Sajah proclaimed themselves new prophets and began spreading their own holy texts throughout their tribes. At a time when the community was still grieving for the Prophet Muhammad, from a Companion’s perspective, this seemed like a slap in the face. One only need to look at the way Abu Bakr’s soldiers perceived the rebellious tribes to see a clear difference between the Ridda campaigns and the expansion campaigns: there was none of the relatively lenient treatment, manumissions of war captives or strict adherence to the Prophetic rules of jihad that characterized the Rashidun expansions to witness in the campaign against the rebels. In the Ridda Wars, after receiving one pre-battle chance to repent and pledge allegiance to the Caliph, any fighting men left after the battle would be summarily executed...

Abu Bakr’s Gambit

... Even though the initial outlook seemed dire, Abu Bakr’s first strategic move was to make a very risky gamble. With the zakat coffers running low thanks to the inability to conduct collections (and Abu Bakr's stern refusal to expropriate the Jewish tribes of Khaybar who had declared loyalty to the Caliphate like Amr ibn Al As suggested), he sent the main body of Rashidun troops to the edge of Syria in the hopes of relieving the loyalist tribes there and raiding the wealthy Ghassanid-Roman outposts. The outcome of this ghazwah would be critical: if the disaster at Mut’ah repeated itself and the army returned empty-handed, the remaining lifespan of the Caliphate would be measured in weeks. Led by Zaid’s youthful son Usama with the help of Khalid ibn al Walid and Umar ibn al Khattab, the soldiers raised the black war banner of Muhammad for the first time since his death and marched for the hinterlands of the Rum. When scouts of the apostate Hawazin tribal confederacy reported that the army of Abu Bakr had been dispatched on a foreign mission, the Hawazin chiefs and their distant relatives of the Bani Ghatafan clan formed an alliance. Large numbers of Bedouin warriors set out from their stronghold at Dhul Kissah to the outskirts of Madinah in a bid to sack the holy city of the Prophet.From their forward base in Dhul Hussah where they met small Muslim bands in skirmishes, the Ghatafan-Hawazin alliance was further reinforced by the proclaimed prophet Tulayha and his Al Tayy tribesmen, swelling their numbers. Tulayha hoped to be the first of the three new claimants to prophethood to capture Madinah, and with only around 500 soldiers left for Abu Bakr to command in defence of the city, Tulayha was already boasting that he'd decorate Muhammad's Masjid with the heads of his widows. Abu Bakr, trying to avoid fighting Tulayha on his own terms and hoping to get the drop on him, takes yet another massive risk on the advice of his councilors Ali ibn Abi Talib, Zaid ibn Haritha and Talha ibn Ubaidallah. He mobilizes every single soldier in Madinah, with even some warrior women like Prophet Muhammad’s foster sister Shaimaa bint Harith [2] joining in, and launches a night assault on the allied rebel army at Dhul Hussah. Despite the number disparity, the Caliph's men (and women) are disciplined veterans of the long war between Muhammad’s Muslims and the polytheist Makkans. With the element of surprise also working in their favor, they utterly destroy the allied army. When the remnants of the broken apostates flee to the stronghold at Dhul Qissah, the Rashidun army pursues them, pausing only for prayers, and captures the oasis town. Tulayha survives the rout, fleeing to his tribe’s stronghold with only 24 men left of his original war party. The victorious army of the Caliph returned home, having successfully defended the Radiant City, and the Ummah settled in to wait for news of Usama’s expedition to Syria.

The Sword of God Takes the Field

We may never know what the week between Abu Bakr's return and the first sighting of Usama’s army in Madinah felt like for the Muslims, but it’s not hard to imagine that deep worry was prevalent. Not only was there a general awareness that this ghazwa was crucial to the fate of Islam, everyone in that city had a brother, son, or husband in that army: Zaid’s son Usama was leading, Ali’s sons Hassan and Hussain were his personal guardsmen, and Abu Bakr’s son in law Hanzalah was in the cavalry. Whatever tensions existed, however, were dissipated when the first Madani scout to spot Usama’s men and greet them returned with the news that Allah had granted the Muslims a clear victory over the Romans. When Usama rode into the city with the Prophet's war flag, proudly heading a army even bigger than it was when it left (bolstered by the soldiers of the loyalist tribes) and loaded down with collected zakat and the Byzantine spoils of war, the people beat drums and sang to celebrate. As the city’s quartermaster Uthman divided the zakat into the various public welfare channels and distributed Roman swords and armor to the soldiers, families reunited for a a week of rest before the war of reunification would begin in earnest.The plan that the Caliph and his shura council split the army into 12 uneven parts -

- Khalid’s Army: Khalid ibn al Walid, aided by Zaid ibn Haritha, Umar ibn al Khattab,Uthman ibn Affan and Talha ibn Ubaidullah, was given command over the largest corps of soldiers. Their task would be to destroy the three major apostate armies threatening the Arabia, linking up with loyalist tribes along the way.

- Ikrimah’s Army: Ikrimah ibn Abu Jahl, advised by Usama ibn Zaid and Hussain ibn Ali, was to lead a small but highly trained force of horse and camel cavalry. Their job would be to tie up the largest of the three apostate forces, that of Musaylimah al Kathab, in harassment attacks and supply line raids so he could not relieve any of the other four or threaten Khalid’s soldiers until the Muslims collected enough loyalists to eliminate him.

- The Provincial Armies: Nine separate commanders selected by the council were each given an equal share of the remaining soldiers. They were tasked with restoring peace to the restive borderlands, like Yemen and Bahrain.

- Abu Bakr's Army: The “Home Guard", so to speak. Abu Bakr, Ali ibn Abi Talib, and Hasan ibn Ali would use the soldiers from the defence of Madinah to guard the Holy Cities of Makkah and Madinah, as well as the nearby agricultural town of Ta’if.

The Rainstorm of Yamamah

Musaylimah was the most hated of the new prophets by the Muslims for claiming that Muhammad had been his “co-prophet” and later “his most loyal and servile follower" in his book of additions to the Qur’an - this was not only heretical but spat on the memory of their beloved Prophet in their view - and they fully intended to punish Musaylimah for it. He was joined in his stronghold by the seeress and fellow new prophet Sajah, who was planning to attack Madinah but decided to combine forces with Musaylimah after Tulayha’s attempt to do the same ended in defeat, and even married her to bind their armies together permanently when he heard that the Sword of God himself was leading an army to destroy him. Ikrimah and Usama had done a magnificent job of harassing him, attacking outriders or scouting parties before vanishing into the night when the main apostate army arrived. Ikrimah kept pushing to assault the army itself, but Usama was able to dissuade him from this course of action: the Muslims were used to fighting as underdogs but not even Khalid could win with such a massive numbers disparity. They kept bleeding Musaylimah daily until one totally quiet week went by. Musaylimah and Sajah believed that Caliph Abu Bakr had despaired of ever conquering the town and threw a lavish party to thank God for their success. Contrary to their optimistic assumptions, Ikrimah and Usama had been contacted by a lone rider who told them Khalid’s army had camped a safe distance from Jawh al-Yamamah and that their cavalrymen were to rejoin the main army for the final battle.Two days later, Musaylimah was hurriedly awakened by a tribesman: the Rashidun Army had been spotted on the Plain of Aqrabah right outside the town. When he heard that the Muslims had only about fifteen thousand soldiers, he swiftly gathered his army of forty-two thousand strong and rode out as quickly as he could to their camp to destroy the Caliph’s men in one decisive strike. This rashness was exactly what Khalid was counting on: once again his enemies had let him pick the terrain for the battle and he'd selected a dry riverbed that served as a natural chokepoint, mitigating the number disparity with Musaylimah’s army. When the two armies prepared to clash, Musaylimah offered Khalid the chance to rule Arabia with him - an offer made famous by Khalid's stinging refusal. Incensed, Musaylimah shouted that he foresaw Khalid in Hellfire forever, but any other Rashidun soldiers who wished to be spared death could join him. Not a single man moved to take up his offer, even in the face of his numbers. Now positively maddened by humiliation and anger, Musaylimah commanded his men to charge and the battle commenced. Like he’d planned, the apostate army’s nearly three-to-one advantage was blunted by the chokepoint - once the playing field was leveled, the experience, training, and discipline of the Caliph’s warriors overwhelmed the rebels. The Rashidun soldiers slew so many of Musaylimah’s men that the gully began to flow in the dry season, but with blood rather than sweet rainwater. The wadi where they clashed would be named the Gully of Blood and the Rashidun Army would be christened the Rainstorm of Yamamah in remembrance of this intense and incredibly violent phase of the battle. The army of Musaylimah, reduced to a paltry eighty four hundred, retreated to the walls of Jawh al-Yamamah and hunkered down. The Muslims, unprepared for a siege, came up with a novel solution. According to a text on the lives of the Companions by Al Tirmidhi, the Rashidun soldiers stood on the backs of the others until Al Bara’ ibn Malik was able to jump over the wall, kill the gate guards, and let in the Muslim army[3]. In the slaughter that followed, almost every one of Musaylimah’s warriors died, with the prophet himself being ended by a well-placed javelin thrown by the Abyssinian ex-slave Wahshi ibn Harb. The only leader to be spared death in combat was Sajah the prophetess: she was granted free passage and later re-converted to Islam. With the stunning victory at Yamamah, the back of the apostate rebellion was broken. The pacification of the border provinces would take another few weeks, but the heartland had been re-unified and the majority of the army was demobilized. Trade routes reopened, people returned to their towns and villages, and the remaining soldiers of the Rashidun Army in the area patrolled the area to root out the bandit gangs that had formed in the chaotic beginning of the war. In the space of five months, Abu Bakr had taken the Caliphate from the brink of ruin to the strongest power in the history of the Peninsula and now the victorious Commander of the Faithful could afford to take up more domestic concerns.”

- Musaylimah Al Kathab is actually named Maslamah, but basically every historian uses the pejorative name that the Muslims called him. It more or less means "Tiny Maslamah the Arch-Liar."

- Shaimaa, IMHO, is one of the top ten most underrated figures of early Islam. She's the daughter of Halimah, the Bedouin woman who raised Muhammad in the desert and she watched him while he was a toddler. According to a few hadith (with weak chains of narration, but I prefer to believe it), when she went to Muhammad to become a Muslim nearly 40 years after they had last seen each other, she slaps him across the face for not recognizing her. The Companions around him move to attack Shaimaa, but Muhammad laughs and hugs her, saying "I know you now, Shaimaa! Bring milk and dates; my elder sister has returned to me!"

- Yes, you are in fact reading that right. The Rashidun soldiers used a cheerleader human pyramid to break into Jawh al-Yamamah. History is weird.

Afternotes

The most incredible thing about the Ridda Wars period to me is how unlikely the story sounds even though butterflies have changed very little at this point. The OTL Abu Bakr really does only control 15-20% of Arabia in the June of 632 with three different rival prophets circling like vultures to feast on the corpse of the Caliphate...and by the December of that same year heads a larger and more cohesive state than Prophet Muhammad ever did. Usama's risky expedition to the frontier, Abu Bakr ending the assault on Madinah with five hundred soldiers, Khalid being a living Marty Stu (well, he's always that) and absorbing or destroying army after army; that's all OTL and attested to by even enemy records like what's left of Musaylimah's holy text and the sayings of deposed Ghassanid chief Abu Luayy. The only thing different in TTL is that Zaid takes the place of his son Usama in Khalid's army, leading to Khalid co-opting Malik rather than killing him with family connections. Usama himself is shifted to Ikrimah's harrassment campaign, helping to reign in Ikrimah's impulsive desire for action which gets him defeated by Musaylimah in OTL.Considering the overall slam dunk that was his re-unification, why Abu Bakr has almost no reputation as a warrior-Caliph is a good question. I personally think he was a victim of his own success: a rebellion that gets wrapped up in a year seems like some small, easily-crushed insurrection and not the collapse of a nation.

Last edited:

This is off to a really good start. This early period of Islamic history is so dynamic, fascinating, and underexposed (in my part of the world at any rate). Hat's off to you.

Thank you all for your kind words! I hope the rest of the TL is just as entertaining for y'all to read as it's been for me to write. We won't linger too long on Abu Bakr: he's an interesting guy but there's not much that butterflies have changed about the period under his Caliphate. I think the next update will be a quick one about the compliation of the first Qur'an manuscript followed by a wrap-up post dealing with all the other domestic initiatives Abu Bakr initiated and the second Caliphal elections.

Subscribed, nice work thus far.

Thanks, mate! Your own Mark Antony TL is fantastic. I wasn't planning on doing any super in-depth military history posts for the ghazawat of expansion before I began reading Dionysus Lives, but seeing what you've done, I've been inspired to do some more reading to emulate it. Keep it up!

Now, I've just realized that I haven't done a narrative post in a bit and I want to fix that. However, instead of cramming one in before we get to the compliation of the Qur'an or Abu Bakr's domestic reign/the Grand Majlis-As-Shura 2: Electric Boogaloo, I'm just going to convert one of them into a narrative. Which one becomes a narrative is a decision that I've left up to y'all. Think of it as our own reader's shura council!

Either we can have a POV post following Zaid ibn Thabit, the book nerd of the Companions, and his valiant efforts to collect all the parchments and hufadh he can to compile the first complete Qur'an OR Zaid ibn Haritha, Muhammad’s golden boy, politicking it up at the Council.

Edit: Spelling errors...

Last edited:

Thanks, mate! Your own Mark Anthony TL is fantastic. I wasn't planning on doing any super in-depth military history posts for the ghazawat of expansion before I began reading Dionysus Lives, but seeing what you've done, I've been inspired to do some more reading to emulate it. Keep it up!

Now, I've just realized that I haven't done a narrative post in a bit and I want to fix that. However, instead of cramming one in before we get to the compliation of the Qur'an or Abu Bakr's domestic reign/the Grand Majlis-As-Shura 2: Electric Boogaloo, I'm just going to convert one of them into a narrative. Which one becomes a narrative is a decision that I've left up to y'all. Think of it as our own reader's shura council!

Either we can have a POV post following Zaid ibn Thabit, the book nerd of the Companions, and his valiant efforts to collect all the parchments and hufadh he can to compile the first complete Qur'an OR Zaid ibn Haritha, Muhammad’s golden boy, politicking it up at the Council.

Thanks! that's very kind of you to say. I'll be sure to cast my vote in the poll.

Love and Holy Books Part I - Zaid and Tawadrosa

Love and Holy Books, Part I

Read! In the Name of your Lord, Who all created,

Created Man from blood, coagulated,

Read! And your Lord is the Most Exalted,

Who tutored by the pen;

What Man knew not, We helped him ken.

--- the first five chronological verses of the Qur’an, Surah Al-Alaq [1]

God makes easy the road to Paradise for those who make easy the road to knowledge.

--- saying of the Prophet Muhammad, recorded in Sahih Muslim

Ten miles outside of Tarim, 633 CE

There were nine beautiful sights a traveler should see in Arabia, said the ancient poems of the Mu'allaqat, and the coming of spring in the well-watered valleys and wadis of Hadhramaut was the most breathtaking of them all. The land was transformed into a garden where fragrant blooms, rich fields of wheat, tall date palms, ruby-red pomegranates, and frankincense bushes grew so thickly, it almost seemed like another world from the surrounding plateau. Many merchants made a healthy profit by purchasing the fruits and grains of the farmers here and selling them in the towns to the north, but two of the riders in the caravan heading to Madinah under the light of the full moon carried no sacks of millet, no crates of olibanum, and no pomegranates with them. The cargo carried by these two travelers was a strange one: scrolls of parchment, dried palm leaves, carefully folded vellum, papyrus-like reed sheets. On these, in a hundred different handwritings, in dialects hailing from Yemen all the way to Bahrain, is written the message that the illiterate shepherd Muhammad received in the Cave of Hira from the angel Gabriel. These scholars amongst traders, Tawadrosa bint Maksant and her husband Zaid ibn Thabit, were bringing the Word of God home with them to Madinah.

Although their long journey was almost at its end, to Tawadrosa, the cool night breeze and the slow swaying of her camel as it headed for the Prophet’s City felt almost like the night she'd begun her own days of wandering. She called herself Theodora, daughter of Maxentius the epidecaon, back then, when she was still a restless young woman. Raised in the old and grand city of Alexandria, she spent her days reading scripture and philosophy alike. A student of languages and the Old Testament in particular, her mother was pleased with how intelligent and well-read her daughter was, but Theodora wasn't content with a life of passive worship. She longed to be a part of the great movements of the past: to have been with the Israelites as Moses lead them out of bondage or to have heard Jesus preach the Gospel with the disciples. The thought that the days of prophecy were over and God would no longer speak to his creation was one that filled her with a hard-to-explain sadness. Her parents were concerned by the change in her demeanor, but could do nothing to alleviate Theodora’s melancholy.

Her mood only broke when she overheard chatter between her family's servants about the trading caravans from the barbarian desert towns to the East that had arrived the other day. One of the servants, a Christian Arab who bought olibanum from them, said that they had spoken of a new prophet who had begun to preach among them. Theodora went to the servant who met the Madani caravan and asked him to take her to their camp. She spent the whole night speaking to the foreign traders in her halting Arabic; they were a poor-looking group, with small weatherbeaten tents and patched garments, but they spoke eloquently about their Prophet and his mission to restore the teachings of the old prophets. The more she listened, the more Theodora was convinced that this was the moment she had been waiting for: a chance to learn from a messenger in the flesh. When the caravan made ready to leave for Arabia, she gathered some of her belongings, a camel from her family’s herd, and a pouch of gold coins. Theodora put on a hooded cloak and rode to the Muslim trader's camp as they were about to set off from the city and asked to join them. Pleased to hear that she wished to meet the Prophet Muhammad, they accepted her into the traveling party. When Theodora rode into Madinah, she was decidedly disappointed; compared to Alexandria, the Radiant City was just a rude collection of mud-brick buildings with palm-thatch roofs. Already beginning to feel like she had made a big mistake, she settled into the first row of worshippers [2] in the Prophet's Masjid and waited to hear the man himself speak. When Muhammad stood on his rough-hewn minbar and began to address the crowd, speaking in his calm and soft tone that still somehow carried across the room, Theodora sat enraptured. Her Arabic was imperfect, but she could understand his words enough to follow along, and what words they were! He spoke of the compassion of God and the compassion that the faithful should embody to the people around them. After the prayer, she walked up to the Messenger and said her shahadah to the jubilant cries of “Allahu Akbar!” from the congregated Ummah. In another few weeks, Theodora was again dissatisfied; she was happy to be in Madinah now that she had met the Prophet, but she was bored doing merchant work in the markets. She wanted to be challenged intellectually, not stuck in a tent selling wares. She voiced her concerns to the Prophet Muhammad, who smiled and told her to call upon a young man named Zaid ibn Thabit.

Zaid had always been small and short for his age. In fact, Zaid shouldn't have even been alive. As a dangerously underweight one year old, he got sick during one of the plagues that swept Makkah every few decades. His mother Ramla, the only adult in his family after his father died in tribal warfare, was told that her son had no chance of surviving and that she should prepare for the funeral. Ramla angrily sent away the healers, telling them that they had underestimated her son’s strength, and soon little Zaid proved her right. “He weakened, he thinned, but by Al-Laat, he lived!” she crowed proudly, words that would come to define Zaid ibn Thabit’s life. People were constantly underestimating him since then, and Zaid was making them look like fools just as consistently. When the refugee Ummah was staring obliteration in the face just prior to the Battle of Badr, an eleven year old Zaid wielding his father's sword tried to enlist in the Muslim army. The Prophet sent him back, kindly telling him that the battlefield was no place for boys. Zaid was so angry that he couldn't fight that he stabbed the sword into the ground and challenged the soldiers gearing up for war to a fistfight. Zaid ibn Haritha, then a strapping warrior in his twenties, took the sword from ground and consoled his younger namesake. The older Zaid promised the boy that he'd wield ibn Thabit’s sword for him in the battle to bring honor to their family. Zaid ibn Haritha brought back his sword for him from Badr and handed it back to Zaid ibn Thabit. "Now it has history", he said to the awestruck boy, who took it home and cherished it ever since. Zaid ibn Thabit did eventually get his chance to win glory in battle [3], but by then he had already taken to sharpening his mental skills instead of his martial ones. When he had been rejected for the army a second time during the battle of Uhud, Muhammad sat with the angry youth. The Messenger told Zaid that there were other ways to serve his community than on the battlefield, roles that the Ummah needed even more than another soldier. Calling him “the most able mind in Madinah”, Muhammad urgend Zaid to expand his own horizons and thus expand the horizons of Islam as a whole. Since that day, Zaid inhaled every book he could get his hands on. When he ran out of books in Arabic to read, he learned Hebrew and studied with the Jewish tribes of Khaybar. Then he learned Greek, then Syriac, then Coptic, then Persian...by his early twenties, Zaid was a scholar to rival any other in the Peninsula. He became the chief scribe to the illiterate Prophet Muhammad, noting down his sayings for later perusal by the Companions, reading letters and parchments for him, and writing responses back in his name.

Zaid was quite content with this simple arrangement, working as a scribe and spending the rest of his time hunting down new reading material; at least he was until Theodora showed up at the door of his small house adjacent to the Masjid. The pretty young Coptic lady introduced herself and said that the Prophet had suggested that she work with him. Zaid was apprehensive at first, shy as he was, but he found himself opening up to Theodora almost in spite of himself. He quickly discovered she was conversant in as many languages he was, knew about philosophies that seemed tantalizingly new to him, and was a brilliant debater. For her part, Theodora never thought she’d meet any Arab in this backwater of the world as educated as Zaid was. He could give lectures on Tertullian or the Desert Fathers, recite achingly beautiful ancient Arabic poetry about the lonely dunes and windswept massifs of the high desert, or talk about the intricacies of Jewish scripture. For two whole weeks, they spent almost every waking moment with each other, either arguing some obscure point of theology or sharing a joke in some foreign tongue. When they finally announced that they were getting married to the Ummah, three months after Theodora first arrived in Madinah, Ayesha was reported to have said, “I wish I knew why it took them so long.” The couple was surprised that the consensus opinion in the Radiant City seemed to be "it's about time" (alas, it seems some unwritten rule of life that the two lovers themselves are the very last people to see how deeply their beloved reciprocates their feelings), but were more than happy to join in the festivities the Ummah conducted in their honor. The Prophet Muhammad himself filled in for Theodora's mahram during the ceremony and Zaid's mother Ramla, who had converted to Islam with her son, acted as his guardian. Happily married, Zaid and Theodora showed no intention of settling into the usual Madani domestic lifestyle. Childless [4], their household consisted of the two of them in a small house absolutely filled with bound manuscripts, loose parchments and scrolls. Zaid showed no interest in obtaining another wife like many othe Companions did; when Talha ibn Ubaidallah ribbed him for being a hen-pecked husband, he just smiled and said "God has been good enough to grant me a wife who is the equivalent of four women in one. Everyday I spend as her husband is a day that I thank my Lord for his blessings on me. Why then, brother, should I seek out other women?" Together, Theodora, daughter of Maxentius, and Zaid, son of Thabit, worked as a husband-and-wife tag team of scholars, continuing their scribe work for the Prophet but also becoming the city’s major sources of secular or non-Islamic knowledge. They were both bright people independently, but together they operated like some gestalt mind of 7th century brilliance. It was only natural that they would be part of the shura council that was formed to discuss the preservation of the Qur’an that Caliph Abu Bakr convened following the Ridda Wars.

Worried about large numbers of people who had memorized the Qur’an that died fighting the apostate rebels, the Ummah pushed Abu Bakr to make some sort of move to ensure the continuation of the God’s Word. Most of the councilors agreed that the solution lied in getting more people to memorize the Qur'an, with plans ranging from financial incentives for the families of hufadh to removing all secular parts of the education that Zaid ibn Thabit's weekday classes for Madinah's children provided to focus solely on Qur'an memorization (unsurprisingly, Zaid flatly rejected this proposal.) Umar offhandedly suggested making one big manuscript of the Qur’an, so that any lettered person could read it. The suggestion was immediately criticized by Amr ibn Al As, who noted that any written version of the Qur’an would have to be ordered by surah in the same way that the Lawh-al-Mahfuz [5] was ordered, and since only the chronological order of surahs was known, the idea of having a book was a non-starter. Zaid ibn Thabit cleared his throat and responded that both him and his wife actually did know the proper ordering of the surahs. The whole council turned around to stare at the pair, who looked back at them calmly, as if they hadn't just revealed earth-shattering news. Theodora explained that every Ramadan, the Prophet Muhammad used to go over the order of the Qur’an as it should be with both her and Zaid, updating the list every year with the new revelations. The last Ramadan that the Prophet had celebrated with his Ummah, scarcely two years ago, he had gone over the list with them twice. They were completely certain of their list’s accuracy, she finished primly, and they could compile a written Qur'an within the year. The old Banu Makhzum chieftain Ibn Masud almost roared from his seat, yelling as he demanded to know why the two of them waited so long to tell everyone. Theodora smiled slightly at him as she responded: well, no one had ever asked them.

[1] This is from Fazoullah Nikayin’s translation of the Qur’an, which tries to emphasize the Qur’an’s nature as a work of poetry. I don't usually shill for books, but I strongly recommend that any non-Arabic speaker who wants to understand more of the rhythm and tone of the Qur’an should get a copy of this book. For people entirely new to the Qur’an, I used to suggest reading Muhammad Asad's more literal translation first, but nowadays, I think reading the Poetic Translation first drives home the feel of the text, which I think is more important that the minutae of translation.

[2] She is actually sitting in the front row, not just some “front row" of the women's area. The gender separation of mosques is alien to early Islam; almost every early source that even sees this issue as something worthy of note makes it clear that women were praying alongside men. Other early sources indirectly imply this as well; I mean, Hafsah and Ayesha were leading Friday prayers, for the Prophet’s sake! The latter-day rationalization for gender exclusion, that men simply couldn't be around women without it being indecent, also wasn't a Rashidun-era sentiment at all; many women spent time alone with men. In fact, breaking this very taboo is what the Companions considered the "moral of the story" from Ayesha's necklace incident.

The Umayyad dynasty is the earliest date found by Professor Esposito for any evidence of the introduction of gender segregation into mosques, not counting very weak hadith that were probably fabrications from the Abbasid-era. This isn't the time yet to discuss the shifting of Rashidun-era egalitarian Islam into the heavily stratified Islam of the late Bani Umayya and beyond, but I find it very interesting to note that things like the mixed gender prayer hall in Germany which recently drew such polarized headlines are actually in some ways a return to the state of affairs 1400 years ago. Any of my lovely readers who wants to learn more about this topic should look into the feminist Islamic scholar Amina Wadud and her work or shoot me a PM sometime.

[3] This is a great story, but I stuck it in the footnotes so it wouldn't derail the post. So, Zaid ibn Thabit is fifteen when the Prophet finally thinks he's old enough to fight with the Muslim army. The battle he was joining was the Battle of the Trench: where all the people who wanted Muhammad's head on a spike from across Arabia formed a Super League of Islamophobia that was only stopped by Salman the Persian’s idea to dig a gigantic ditch around the city. The Makkan cavalry was stopped and the Muslim archers just filled any Makkan soldier who felt like trying to cross the ditch with arrows. The Makkans and co. are stumped, until someone remembers Abu Dhujanah. Now, Abu Dhujanah is a mercenary, famous for being a great swordsman and even more famous for doing trick jumps with his horse to please crowds. The Makkans hire Abu Dhujanah to jump over the trench and kill Muhammad, hoping that the death of the Prophet would break the morale of the Madanis. Abu Dhujanah actually manages to make it to the other side with a heroic leap of his horse….only to be immediately impaled in the throat by Zaid, who stuck out his spear at the onrushing horseman in reflexive fear. Teenage Zaid sorta accidentally killed the Evel Knievel of 7th Century Arabia.

[4] None of the contemporary sources comment on why the couple had no children, but Az-Zamakshari speculates that Zaid had what we would probably diagnose today as immune infertility. Although they were otherwise healthy men, infertility seemed to crop up in a few boys every generation in Zaid's family. This was a point of some sadness for Zaid, who loved children, but lead to his long and distinguished career in teaching when Theodora suggested that he could help the children learn their letters.

[5] The Lawh-al-Mahfouz (often translated as the Preserved Tablet) is what Muslims call the the great book in which God wrote at the beginning of time, detailing the fate of everything that was ever to come. In the Muslim version of the "Genesis" story, so to speak, the first thing God creates is not light, but the pen. God then creates the Tablets and commands the Pen to write upon them everything that would come to be. It is also said to contain all the knowledge of the heavens and the earth, and perfectly preserved versions of the Scrolls of Abraham, the Testament of Moses, the Psalms of David, the Gospels of Jesus, and the Qur’an of Muhammad.

Afternotes

Remember when I said the update about the compilation of the Qur’an was gonna be a short one? Yeah, it looks I lied. It's got two parts now.

In the first part, you got introduced to our heroes, Zaid and Theodora. Just a quick note on historical sources, I was pretty shocked to see that I couldn't find a single source translated into English on her. There's a solid few in Arabic, both contemporary like Abu Hurairah’s account of her and later but reliable like Az-Zamakshari’s detailed biography of her in his book on the female companions of Muhammad. It's downright criminal that Theodora doesn't get the recognition she deserves (probably because as a member of the rationalist Mu’tazila school, all of Az-Zamakshari’s fantastic work was suppressed by the anti-rationalist Ash’ari school), not only because she was a Companion who played a key role in the compilation of the Qur’an, but also because I think that her and Zaid ibn Thabit’s love story is really cute.

In OTL, Zaid is one of the few male Companions who remains monogamous. Though the reasons for this aren’t clear, we do know that they were quite devoted to each other, to the point that the other Companions often referred to them as a single unit. This love story ends tragically however. During the chaos of the Fitna, Theodora (who was an outspoken partisan of Ali’s faction, while Zaid was more neutral) gets assassinated by a member of Banu Umayya while giving a public lecture in a masjid. Although historians think that it was unlikely that Mu’awiya himself called in the hit on Theodora, Zaid clearly thought Mu’awiya was responsible for her death. Mu’awiya made many attempts to get in Zaid's good graces; as the lead compiler of the Qur’an, Zaid had an immense amount of respect from the Ummah which would help his government's legitimacy. Zaid was having none of that; when Mu’awiya once asked what he could do to repair their relationship, Zaid coldly told him that he could ask God to resurrect his wife. Both Zaid and Theodora were ardent believers in the process of shura and in his waning years, Zaid often said that he was glad his beloved Theodora died before she could see the perversion of the Majlis into a powerless rubber-stamp body. He does teach many students during his later years, becoming the primary Islamic influence for the Abbasid-era Mu’tazila rationalist school (which is probably why Az-Zamakshari wrote so much about Theodora) before dying.

I'm a flatly unashamed sentimentalist and I don't think I'm giving away too much (that couldn't already be guessed at by the direction of the TL so far) by saying that I'm gonna give these two a happier ending than the heartbreak of OTL.

Last edited:

As soon as I saw the name, I went to google to try and find out more about Theodora. A shame to see that there are almost no English sources on her; she seems like a very interesting woman. Great work bringing light to her!

As soon as I saw the name, I went to google to try and find out more about Theodora. A shame to see that there are almost no English sources on her; she seems like a very interesting woman. Great work bringing light to her!

I wish I could take the credit for independently coming across her, but to be fair, I first heard about her myself from a lecture given by Dr. Abdul Aziz al-Harbi on the early Islam's Coptic influences. The most famous early Coptic convert is the wife/concubine (depending on who you ask) of the Prophet Muhammad, Maria Al-Qibtiya, or rather uncreatively, Mary the Copt. Even though she was married to the Prophet, good luck finding more than a paragraph on her in English. Dr. al-Harbi's thesis was that the Coptic influence on Islam was heavily downplayed to try and emphasize the "Arabness" of the Companions during the Umayyid dynasty.

Without Az-Zamakshari and his obsessive need to dig out the oldest possible sources to cite for his books, I'm certain there would be scores, if not hundreds, of facinating Companions that would be totally forgotten by history. I might try to get my Imam to translate parts of his "Stories from the Lives of the Blessed Women who aided Prophet Muhammad" into English later this week to post some stuff from the man himself.

Last edited:

Yeesh, I've never heard of Theodora (what's her name in Arabic again?) before. I've heard of the scribe Zaid though ... Thanks for showing us more of the Companions and their lives.

Her name would be تواضروسة in Arabic, which is usually transliterated in English as Tawadrosa. It's a pretty good approximation, although perhaps Tawadrosah is a little closer. Much like Theodora is the feminine of Theodore, تواضروسة is just the feminine of تواضروس. The letter at the end of the Arabic script Tawadrosa is called a tāʼ marbūtah, and it signifies that a word is feminine just like the "a" at the end of Theodora.

New here, but long time lurker!

I must say I take great interest in this story you've set up. I enjoy it very much. One thing I think you should potentially consider are the Non-Arab companions of the prophet and potentially how they could be used potentially for translation of the Qu'ran or propagating it to non-Arabs similar to how we find translations and transliterations beside the Arabic text of today. Salman al Farisi, and Bilal ibn Rabah come to mind. I feel a joint effort may be more likely than Zaid knowing so many languages.

Also, I'd like to know more about the standardization of the Qu'ran. I was under the impression when the Qur'ans were burned, it had nothing to do with the seven different styles of recitation, but with the religion spreading to Non-Arabs (Assyrians, Persians, Copts). I'm under the impression that the variant Arab readings are still in use. The standardization of Uthman was focused on adding dots to letters to make it easier for Non-Arabs as well as adding tashkeel. (Fatha, Kesra, Thumma) Not only limiting it to Qurayshi readings.

Edit: I also thought I'd add, that while there truly was no physical barrier in the prophet's mosque, there had been a divide as to where women are to sit/stand in Jama'ah. IMHO this is evident because this is overwhelming norm and practice in the world's mosque. If this were more grounded it would be more prevalent such as we see minor differences in the actions of salah. This is an issue which falls under ijma or islamic consensus based upon the actions of the prophet and his sayings.

Might I add that while dealing with the public the Prophet used to keep his wives and children separated from the public and they were generally given slightly higher expectations which are stated in the Qu'ran. I feel its unlikely they would be permissible to stand side by side with men in the front row whilst given these directives.

While Aishah was most certainly a vocal individual, she herself followed typical gender segregation when she used to teach aqeedah (theology) and fiqh (law). She used to set up a curtain between her male and female students when she taught classes.

Edit: Another edit. I think you might mean Athari? Common misconception that Ash'ari aren't rationalist. Ash'ari used Mu'tazili rationalism and combined it with Athari talking points to cause Mu'tazili decline. Athari are more traditionalist. Mu'tazili rationalist. Ash'ari/Maturidi are also rationalist, but more moderate than Mu'tazili and Athari.

I must say I take great interest in this story you've set up. I enjoy it very much. One thing I think you should potentially consider are the Non-Arab companions of the prophet and potentially how they could be used potentially for translation of the Qu'ran or propagating it to non-Arabs similar to how we find translations and transliterations beside the Arabic text of today. Salman al Farisi, and Bilal ibn Rabah come to mind. I feel a joint effort may be more likely than Zaid knowing so many languages.

Also, I'd like to know more about the standardization of the Qu'ran. I was under the impression when the Qur'ans were burned, it had nothing to do with the seven different styles of recitation, but with the religion spreading to Non-Arabs (Assyrians, Persians, Copts). I'm under the impression that the variant Arab readings are still in use. The standardization of Uthman was focused on adding dots to letters to make it easier for Non-Arabs as well as adding tashkeel. (Fatha, Kesra, Thumma) Not only limiting it to Qurayshi readings.

Edit: I also thought I'd add, that while there truly was no physical barrier in the prophet's mosque, there had been a divide as to where women are to sit/stand in Jama'ah. IMHO this is evident because this is overwhelming norm and practice in the world's mosque. If this were more grounded it would be more prevalent such as we see minor differences in the actions of salah. This is an issue which falls under ijma or islamic consensus based upon the actions of the prophet and his sayings.

Might I add that while dealing with the public the Prophet used to keep his wives and children separated from the public and they were generally given slightly higher expectations which are stated in the Qu'ran. I feel its unlikely they would be permissible to stand side by side with men in the front row whilst given these directives.

While Aishah was most certainly a vocal individual, she herself followed typical gender segregation when she used to teach aqeedah (theology) and fiqh (law). She used to set up a curtain between her male and female students when she taught classes.

Edit: Another edit. I think you might mean Athari? Common misconception that Ash'ari aren't rationalist. Ash'ari used Mu'tazili rationalism and combined it with Athari talking points to cause Mu'tazili decline. Athari are more traditionalist. Mu'tazili rationalist. Ash'ari/Maturidi are also rationalist, but more moderate than Mu'tazili and Athari.

Last edited:

Info Post 1: Theories on the Qur'an

New here, but long time lurker!

Glad to have you here, mate!

I must say I take great interest in this story you've set up. I enjoy it very much. One thing I think you should potentially consider are the Non-Arab companions of the prophet and potentially how they could be used potentially for translation of the Qu'ran or propagating it to non-Arabs similar to how we find translations and transliterations beside the Arabic text of today. Salman al Farisi, and Bilal ibn Rabah come to mind. I feel a joint effort may be more likely than Zaid knowing so many languages.

As far as the non-Arab Companions, Bilal is actually slated to make an appearance very soon, during the Second Grand Majlis-as-Shura. I haven't thought about working in Salman al-Farisi, but now that you mention it, the guy's life story was so wild that he's got feature in here somehow. Consider it done! As far as Zaid's language skills, that's not actually my own addition. It seems like sources (I'm generally looking at the Umayyad-era compilations on the Companions) agree that Zaid was at least quadlingual, with Abdallah ibn Masud's (weak) narration claiming that he knew as many as seven languages. I'd take that one with a grain of salt

Also, I'd like to know more about the standardization of the Qu'ran. I was under the impression when the Qur'ans were burned, it had nothing to do with the seven different styles of recitation, but with the religion spreading to Non-Arabs (Assyrians, Persians, Copts). I'm under the impression that the variant Arab readings are still in use. The standardization of Uthman was focused on adding dots to letters to make it easier for Non-Arabs as well as adding tashkeel. (Fatha, Kesra,

The problem with the Qur’an burnings is that they're probably behind only the assassination of Uthman and the murder of Hussain at Karbala for the title of "most politicized event in early Islamic history." The traditional Sunni account claims that the modern seven styles of recitation were always just that: styles of recitation that had no actual difference in wording. In this account, Uthman only burned the adulterated copies spreading like wildfire across the Caliphate's fringe regions.

On the other hand, some branches of Shi'a Islam (a number of Alevis for example) go so far as to claim that all the other Qur'ans burned by Uthman had verses talking about how Ali should be Caliph, so he doctored one Qur'an and destroyed all evidence.

Since a goal of this TL is to be nice and non-sectarian, I think we should try to use the recent renaissance of relatively unbiased historical research into the Rashidun Caliphate to inform our official position on this tricky subject. To dismiss the Alevi position, all we really need to consider is Occam's Razor; which is more likely? That Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman made a conspiracy to destroy and replace every copy and every reference to a some explicitly pro-Ali version of the Qur’an without any other Companions saying anything....or that the Qur'an simply never had any pro-Ali verses? However, the traditional Sunni position falls apart under scrutiny as well; the smoking gun here is the existance of several documents like the Sana'a Manuscripts, which prove that there were indeed notable differences between the pre-Uthmanic Qur'ans. Analysis of the differences show that the older variant Qur'ans are still essentially unchanged in meaning, but conform to the rules and vocabularies of archaic regional dialects. Now, we can construct a likely narrative from this: the modern seven styles of reading started out as fully-fleshed variant dialect Qur'ans, but with the standardization of the Qurayshi Qur'an under Uthman, they fell into disuse and atrophied into the cosmetically different accents we see today. This understanding of how the current Qur'an came to be is the one this TL assumes to be true.

....in retrospect, I probably should have explained all this some time back.

Edit: Nice catch, I did in fact mean Athari in reference to anti-rationalism. The Ash'aris are probably the more famous opponents of the Mu'tazila, but you're correct in pointing out that they aren't anti-rationalist, just anti-Mu'tazila rationalism.

Edit, yet again: As far as the question of gender segregation, there is an interesting argument made by Ibn Taymiyyah (yep, the famously conservative one) that the general norms around gender he saw around him, like gender-segregated mosques and women being kept from leading jumuah, were not inherent to Islam but were instead cultural practices that had become attached to the religion that could be shed without any sin. This by itself is neat coming from Ibn Taymiyyah, but since it's theoretical, it's not directly applicable. What makes his argument really interesting is the example he draws on to make his point; particularly a narration detailing gender-mixed congregation at mosques in the city of Kufa under Caliph Ali, simply because the customs there didn't hold with gender segregation.

P.S: If you'd like, we can continue this in PMs.

Last edited:

This continues to be fantastic and provides immense insight into a period and topic I know very little about.

I honestly don't have a lot to say given how little I personally know about it but I hope you keep it up.

Oh, and regarding the whole discussion on the Koran, I am learning a ton from just reading comments, so I would be a bit put out if I couldn’t keep on following along

I honestly don't have a lot to say given how little I personally know about it but I hope you keep it up.

Oh, and regarding the whole discussion on the Koran, I am learning a ton from just reading comments, so I would be a bit put out if I couldn’t keep on following along

Love and Holy Books Part II - Compiling the Qur'an and the writing of Noor-ul-Ikhlas

...speaking of Qur'ans

Love and Holy Books, Part II

We have ordained for every nation,

Their way of worship and devotion,

That they observe; thus let them not

Dispute with you about this question;

But bid unto your Lord, for surely

You are upon the right Direction.

--- The Qur’an, Surah Al-Hajj (22:76)

“If you expect the blessings of God, be kind to His people.”

--- saying attributed to Caliph Abu Bakr

Charged by the Majlis-as-Shura and the Caliph himself with a task no less momentous than the preservation of God’s final message to humanity for generations to come, Theodora and Zaid discussed where to start over a meal of harisa once they had returned to their home. More accurately, Theodora was discussing where to start; Zaid was trying his level best not have a panic attack. Ever since the Prophet had gone over the divinely ordained order of surahs in the Qur’an the second time during the final Ramadan before his passing, Zaid had a notion that he would have to do something akin to this, though he felt excited by the idea at the time. Now that the great work was finally at hand, however, he felt like he was going crack under the pressure. “By the Most Merciful, how will we even go about something so big? Who should - I mean, what do we - I mean, how will…” Theodora looked up from the gazelle-hide parchment she was reading and saw that her husband was close to spiraling. “Habibi, listen. No one else from here to Kisra’s palace is more prepared to do this, we'll be alright. There are no insurmountable problems ahead of us, only difficult ones. ” Zaid stopped walking back and forth like a caged animal and sat down next to her. “But what if we make a mistake? If we carelessly change the meaning of a verse and lead our fellow Muslims into error, that sin will be on us, and…” Theodora shushed him before he could that line of inquiry. “Simple, we won't make any mistakes.” she replied once he had quieted, half-joking.

In control of himself again, Zaid handed Theodora the parchment with the ordered list of surahs she had been reading, stretched out a fresh parchment, and dipped his reed qalam in fresh black ink. “Then we'd better come up with some way of ensuring the accuracy of every verse we copy into the manuscript. Any thoughts?” She rolled up the list and returned it to a box filled with other marked-up sheets, “How about requiring five separate documents written by different people that contain identical verses for each surah, then doing the same thing again but with five hufadh instead of documents. If we can find that much evidence supporting a version of a surah, it's accurate enough to enter into the masa’hif.” Zaid nodded and wrote down the criteria onto the parchment with the neat, angular script that came naturally to him. He didn't even look up from his work as he continued talking to Theodora, his reed pen gliding across the writing surface with practiced motions. “We’ll have to be careful to keep the different dialect styles separate; we can do the Qurayshiyyah variant first, since it’ll have the most easily available documents, and then get to the others afterwards.” Now it was Theodora's turn to look at him with skepticism; “Will Banu Makhzum and the rest of Quraysh allow us to present the other six masa’hif alongside their own?” Zaid set down his pen and sighed deeply before responding. “If God wills it, habibti.” They chuckled together at that; saying “inshallah" in response to a question was just about the best non-answer you could use. Zaid felt somewhat better now, despite all the responsibility still weighing on them. They had a plan and that was what mattered.

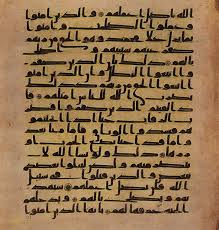

Excerpt from "A Modern Historiography of the Qur'an", Louise Schumer

“The creation of the seven Masa’hif of Abu Bakr was the culmination of a year and a three months worth of almost nonstop work on the part of over 55 scribes. Although finding enough people who had memorized the Qur’an was relatively simple, even rare variant styles like Ta’ifiyyah had hundreds of people who memorized surahs using it, the real challenge faced by the group led by Zaid ibn Thabit and his wife Tawadrosa bint Maksant was in gathering the written records they needed to make certain that there would be no errors in the production of the final set of masa’hif. Literacy was still rare this early into the Rashidun Caliphate and most people who could write didn't advertise that they had written copies of surahs. People who wrote down Qur'an tended to do so for their own benefit, so figuring out who had what surahs written was an ordeal. Although Caliph Abu Bakr theoretically could have ordered everyone with written texts of the Qur’an to arrive in Madinah and hand over their parchments or reed papers for copying, the Caliph decided that disrupting the rebuilding efforts and calling away soldiers from the borders so soon after the Ridda Wars was not feasible. To get the documents they needed, the team of scribes had to disperse throughout Arabia, hunting after every lead they could to get to the five documents they needed per surah. An average week could see a scribe searching in Makkah for a man who a farmer miles away in Mahra remembered selling a scroll with Surah Al-Ahzab written down on it, only to learn that the man they're looking for has left with a trading caravan to Syria. Unable to waste precious months waiting for him to get back, the scribe rides for a day and night almost nonstop to catch up to the man and collect his scroll. In this manner, Zaid and Tawadrosa were able to collect the 3990 written records required to certify the seven final manuscripts. Zaid carefully wrote every letter on every page of each manuscript, with four different junior scribes checking after him to catch any mistakes. When it was all done, Tawadrosa gave them a final read through and bound them into seven completed books with the help of her aides. The very next day, Madinah’s resident scholar-couple and their team of dedicated scribes proudly presented the newly-christened Masa’hif of Abu Bakr to the community at the Prophet's Masjid. When the seven large books were brought out for viewing, a reverent hush fell over the previously energetic crowd. Everyone got their chance to quietly approach the texts, turn the pages, and read a few verses to themselves. Even illiterate Muslims came forward to run their fingers over the words and admire the craftsmanship involved..."

"...When some of the leaders of the Qurayshi subclans learned that the other variants of the Qur'an had also been compiled, they protested the move in the Majlis-as-Shura. “Did the Prophet not recite in the Qurayshiyya style himself, and would not having seven different forms of Qur'an confuse those who wish to learn it?” they said to the council. Caliph Abu Bakr, despite being himself a man of Quraysh, sternly chastised the sheikhs of his tribe. “Are they not equally the words of our Lord, the Most High? Did not our Prophet, peace and blessings be upon him, also teach us these other styles, so that our brothers and sisters may have a Qur’an easy for them to recite and we may enjoy the beauty of their recitation?”, said the Caliph with irritation. “You should have been elated that our noble book, multifaceted like a jewel, is to be preserved as it was revealed. Instead, you chose to let your hearts slip back into the days of ignorance, when furthering the agenda of a tribe was the only aspiration you had. Reflect on your errors and ask God for forgiveness.”

"Whether Banu Makhzum and their affiliates were genuinely remorseful or just smart enough to avoid picking a fight with the most powerful man in Arabia, they didn't bring forward any opposition to the codification of the six non-Qurayshi Qur'an variants again. However, Zaid wasn't done shaking up the council just yet. Later that same day, he announced to the Majlis that he intended to write his own book to accompany these new masa’hif, one that he hoped would help teach other Muslims how to approach the study of the Qur’an and Islam in general. Uthman asked Zaid why he thought this addition was necessary: everyone in the room could improve their knowledge of the faith some, but no one here was a beginner. “Indeed, my brother,” Zaid said as he got up to project his voice, “but what about the people converting every day on the border provinces? What about the Muslims who will come long after we have entered the grave? We were blessed to have learned at the feet of Prophet Muhammad himself, peace and blessings be upon him. It is the height of selfishness for us of the Companion generation to hoard our wisdom and take all our knowledge with us to the Akhirah when we pass. Like we have preserved the Word of God for times to come, let us also preserve some small part of the wisdom that our teacher and Messenger left us with.” Many of the gathered Companions were nodding in agreement by the time he was finished, but several others looked less convinced. Uthman objected, saying that he was worried that in the distant future, Muslims with only rudimentary knowledge of the faith could confuse Zaid's text with the text of the Qur’an. Several others agreed with him, murmuring their assent. Caliph Abu Bakr decided to allow the council to come to a decision on the matter, as he was unsure himself on whether the merits outweighed the possible risk, and after some prolonged debate that featured Umar and Zaid ibn Haritha passionately arguing for the inclusion of Zaid’s treatise, he was given the OK to begin writing a text to be paired with the manuscripts."

Excerpts from "Heirs to Muhammad: The Generation of Companions and their Successors"

The book that eventually became famous as Zaid ibn Thabit’s magnum opus is a slim volume, hardly more than 26,000 words in all. On prominent display thoughout the text are Ibn Thabit's unique theological views, which are primarily based on his individual reflections on the relationship between Muslims and the Islam they profess, but also clearly incorporates elements of Neoplatonist thought in his discussion of the primacy of intellect in discerning truth and his implication that the Qur’an is a creation of God instead of an eternal truth. Two factors seem to have primarily been at work in sparking the creation of Noor-ul-Ikhlas: the first was an attempt to ensure that a crisis like the narrowly-avoided catastrophe of the succession to the Prophet, the first time Zaid had seen widespread conflict between fellow Muslims, would never happen again. The second catalyst was Ibn Thabit’s rather far-sighted realization that once Islam was triumphant in Arabia, Muslims would have to restructure the way they introduced the Prophet's Message to others in order to win the hearts and minds of potential converts beyond their borders.

After a self-effacing opening (typical of Muslim writings of this era) where he calls his treatise “a book of little worth that may provide some small benefit", Zaid launches directly into a discussion of the role of reasoning in religion. To him, the aql or intellect is the greatest gift God has given to mankind; with it, humanity can discover natural truths about the world for itself and discern revealed truths from scripture. God intended for every Muslim to use their gift of intellect to interpret Islam for themselves within the guidelines of the Prophet's clearest rulings. There were no clerical positions in Islam because Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, wanted everyone to understand their relationship to God personally, free from the dictates of so-called authorities. He tells his readers to recall that God has said in the Qur’an that he is closer to humanity than our jugular veins. If God is so close to every person, Zaid opines, than having an intermediary like a priestly class is not only unnecessary, but in fact, presumes upon God's divine right to have an truly individual relationship with his believers. Zaid then briefly discusses the main tenets that all Muslims should hold, using the Hadith of Gabriel as a model to succinctly describe the major articles of faith and practice.

Next, ibn Thabit addresses the possibility of different personal interpretations of the Qur’an and Sunnah leading to differences in practice. Zaid reminds his readers of the well-known event during Ghazwah Tabouk, where two groups of Muslims disagreed about what time the Prophet had meant when he instructed them on when to stop for prayer. “If even men like us...”, he writes, “...who spoke the Noble Prophet’s tongue, marched behind his banner, and heard his commands from his own lips, could disagree on what he intended, is it not folly to believe that the coming generations of believers will never disagree on questions of faith?” If the decisions you decide to follow differ from those of your brothers or sisters in Islam, do not impose your decisions on them, Zaid warns sternly. Not only would such a person have commited the sin of forcibly exerting their will over the will of their fellow Muslims, but they would also be guilty of the even more heinous sin of stripping another creation of God of their right to use their intellects as the Almighty intended. What matters to God is not the detail of religion itself, but the sincerity with which you try to understand what God wants and the devotion with which you practice it. He quotes a verse from the Qu'ran on animal sacrifice where God says: "Their flesh and their blood reach not Allah, but the devotion from you reacheth Him." To illustrate his point, he cites the end of the story concerning the prayer time dispute, relating how the Prophet settled the matter in the end by saying both sides were rewarded by God for their ikhlas. In his conclusion, Zaid implores the reader to remember the Prophet's example of compassion and ends by writing that the whole of his work can be summarized in one saying of the Prophet: “Verily, actions are judged by intentions.”

Added in front of the manuscripts and copied with it when the Qur'an began to be distributed to the provinces under later Caliphs, it's impossible to know exactly how influential Noor-ul-Ikhlas was, but it's would not be an overstatement to say that it formed the intellectual basis for a significant fraction of schools of jurisprudence and Islamic philosophies alike for the next four centuries. Although many present-day Muslims point to al-Noor-ul-Ikhlas as evidence that Islam is the grand progenitor of its own native progressive tradition, these kinds of editorializing statements are groundless attempts to paint 21st century values onto what remains a deeply 7th century text. Yes, Ibn Thabit praises the shura council and says that the will of the Ummah as a whole is the only institution of governance that is guided by God directly, but he also declares that the elected Caliph “should rule his people with a strong hand, like a general rules his army.” In religious matters, he tells people to think for themselves and be wary of those who would seek to institute a pseudo-clergy, but in government, Zaid instructs his readers that unless the shura council has decided that the Caliph broke a central tenet of governance (creating compulsion in religion, refusing to allow the shura council to elect the new Caliph, abandoning their God-given duty to protect the weak and reign in the strong, etc), they must give the Caliph their absolute and total loyalty even when they personally feel like the Caliph is in error. Ibn Thabit writes eloquently about tolerance between Muslims and the strictly forbidden nature of forcing a non-Muslim to accept Islam, but he sees no problem with waging wars of conquest to add foreign land to the Caliphate. In total, though a libertine in religious matters even when compared to some modern believers, the ideal government as envisioned by Ibn Thabit is one where an elected benevolent dictator, who is only loosely limited in power by a quasi-republican council, runs all affairs of state; this is hardly a democratic oasis in a desert of tyranny. Despite all of these caveats, many historians do agree that when taken in the context of the time period during which it emerged, Noor-ul-Ikhlas was nothing less than the manifesto of a revolutionary firebrand.

Whether further developing ibn Thabit's thesis or acting in reaction to it, Zaid's “book of little worth" informed the discussion around Islamic theology and governance for generations. However, one little-explored ramification of Noor-ul-Ikhlas was the impact it made on non-Muslims in the Caliphate and without. Translated by the author and his wife into a number of languages and bound together with manuscripts of the Qur'an, it became the first encounter to Islamic beliefs and thought for thousands of people. Zaid's multilingual eloquence, his masterful framing of a new kind of religiosity that drew on the virtue of tolerance just as heavily as as it did the virtue of piety, and his quasi-Neoplatonic direct appeal to the rationality of the reader made The Light of Sincerity a work that left a lasting impression even on those it did not convert. If the jostling of empires in the 7th century’s Near and Middle East can be understood as a running battle fought on intellectual lines as often as physical ones, Zaid ibn Thabit had just given the young Rashidun Caliphate the cultural equivalent of the atom bomb."

Afternotes

Now that the post on the Qur'an is complete, just how important our other protagonist named Zaid is to TTL’s Rashidun Caliphate becomes clear. The first and maybe the most attention-grabbing divergence from OTL is the collection of not one, but seven variant Qur'an manuscripts. Once again, this TL adheres to what has been called the “synthesis” position on Qur’an history: at least seven Qur'an dialects were both memorized and recorded in personal manuscripts prior to Caliph Abu Bakr commissioning Zaid ibn Thabit to create the first manuscripts. Though documents like the aforementioned Sana’a Manuscripts prove that the other variants were still in use well up to the standardization of the Qur'an under Uthman, they were never compiled into a highly authenticated single “founder manuscript" that could be confidently copied and distributed like the Qurayshi Qur'an. The reason why this is remains unclear and the topic of hot debate, but for our purposes, we'll take the popular opinion that Abu Bakr may have bowed to pressure from elements within the Quraysh to keep from compiling the others. This theory is both plausible in scope (in that Abu Bakr wasn't forcing people who used variant styles to stop, they simply weren't authenticated) and was a rational move for the Caliph (who had only just gotten a still-resentful Banu Hashim back on board and didn't want to antagonize them.)

In TTL, however, Abu Bakr's legitimacy is iron-clad and he doesn't have to walk on eggshells to make sure every major faction in the Majlis is content. Instead of being forced to humor their opinions on compiling the other six Qur'an manuscripts, TTL’s Abu Bakr can just tell them to shut up. Knock-on effects of this Qur'an pluralism will be interesting, since in OTL, the Qur'an compiled under Abu Bakr's reign was the one used by Uthman for his standardization program. TTL may still see a smaller-scale version of the Qur’an burnings, but instead of replacing the unverified ones with just the Qurayshi variant, there will be seven “founder manuscripts" that will be standardized, copied, and sent around the Caliphate.

The other big change from OTL is that Zaid ibn Thabit's proposal to author an introductory text to be associated with the manuscripts is approved instead of rejected. I've attributed this change to Zaid ibn Haritha coming down on the side of his fellow Zaid, but I'll admit that I've loaded the dice on this one. Zaid ibn Thabit's proposal made quite a few people skittish about later Muslims accidentally considering his text part of the Quran, but in TTL, vigorous support from Umar and Zaid ibn Haritha together push it through successfully. Since the book was never written, I ghost wrote for Zaid, who I represented with a proto-Mu’tazila philosophical position with a heavy sprinkling of Neoplatonist thought absorbed from his Coptic wife Theodora. Although Noor-ul-Ikhlas will be theologically important, the most influential part of the text will be its discussion on government.

While the current Caliphate has a representative body and elected Caliph, politics is still incredibly personality-driven and there's no formalized way of appointing people to the Majlis-as-Shura. As it stands, it remains a pretty precarious system and one bad crisis could send the house of cards tumbling down. In his discussion on government, Zaid proposes a shift from tribal representation shura to territorial representation shura, where Caliphal authorities would oversee the selection of provincial governors by local vote. Those provincial governors would then form the Majlis-as-Shura, who could elect one from amongst themselves the Caliph. This isn’t actually a very radical change, since this is similar to the way that sub-tribes are already supposed to have their own local shura council to pick which tribesman will represent them to the Majlis, but the relatively standardized and formal nature of the governor-elector system is more stable than the fluidity of tribal politics. It's a yet unrefined system that still cherishes the idea of a benevolent dictator Caliph and a lot of other very medieval beliefs, but with his book, Zaid has laid the foundations for a Rashidun Caliphate with the stability and staying power to last beyond the Companion generation.

Last edited:

Really like the TL, especially the chapter on Theodora. I'm more familiar with Aishah (RA) and Khadijah (RA) then the other wives of the Prophet (PBUH). There are countless books on Aishah in malay but most books usually gloss over the other wives of the Prophet and my Arabic at best is mediocre... Also ITTL's Majlis as-Shura seems to have turned the Caliphate into a Democratic Federation.

(alas, it seems some unwritten rule of life that the two lovers themselves are the very last people to see how deeply their beloved reciprocates their feelings)

I love when TLs add in sweet little asides like this. Really fascinating stuff in this two-part chapter! Can't wait to see how this "atom bomb" plays out in the Levant.

Threadmarks

View all 26 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

A Bit of a Timeskip - The Ascension of Caliph Maxentius "To Jerusalem! To Damascus! To Rome!" Part I - The Final Battle in Iraq, Trouble in Madinah, and the Beginning of Ghazwah As-Sham "¡Marchamos con nuestros hermanos!"/"We march with our brothers" - A War Song of Khalid's Christian Mujahideen (by Halocon) Info Post 7 - The Possible Development of Jewish Leadership in the Caliphate (by Jonathan Edelstein) Quiz on the Caliphate! Quiz on the Caliphate - Answers! "To Kisra and Beyond!": How the Arabs ran the Iranians out of Iran - Part I "To Jerusalem, To Damascus, To Rome!" - Part II

Share: