You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Remember the Rainbow Redux: An Alternate Royal Canadian Navy

But, for example, the above article says that the Earl Grey's own Rifles were authorized in May 1914, but the following newspaper article says they were disbanded in March 1914. https://www.thenorthernview.com/opinion/in-our-opinion-names-missing-on-cenotaph/

I have encountered more sources that say the Earl Greys did not exist at the start of the war. But the individuals would be in place. And they would retain their equipment. Which, judging by the most common photograph, consisted of a dozen jackets, a dozen caps, and a snare drum.

From what I have seen researching over the weekend, Earl Grey's Own Rifles existed in some capacity as far back as 1910. The photo you shared is apparently their first parade according to some sources I have seen online, albeit without much of their military trousers and small arms. I have found the following with regard to the Earl Grey's as a unit at this obscure pdf.

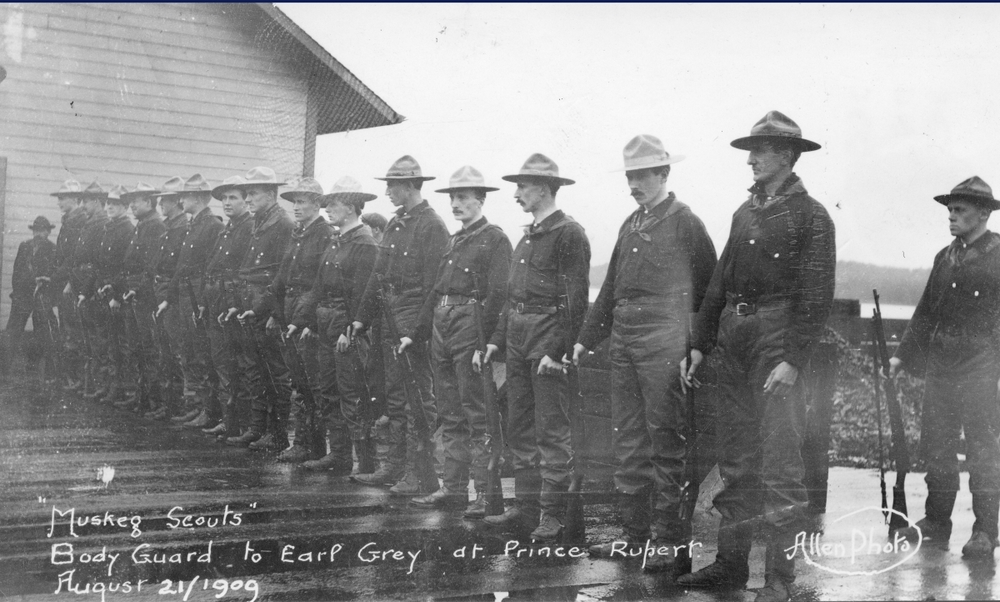

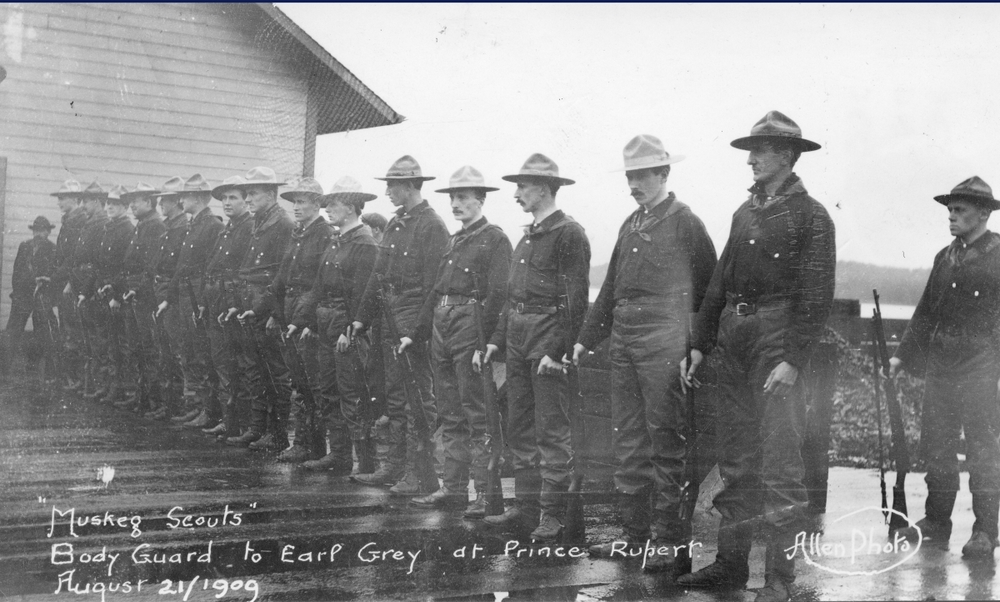

The Earl Grey’s were said to have been started by a John Beatty. He arrived in Prince Rupert in 1908 beginning his freight business with a wheel barrow, and brought in the first horse team for the cartage business – the kind of man Reginald Thelwall may have worked for running his teams of horses. Beatty organized the first militia company, known as the ‘Muskeg Scouts’ which evolved into the ‘Earl Grey Rifles’ in 1909, which he also helped to organize. [‘muskeg’ is the western Canadian term for grassy bog, which the pioneers were busy reclaiming in Prince Rupert] . They were commissioned and authorized on 1 May 1910. On 2 November 1914 they were re-designated ‘68th Regiment (Earl Grey`s Own Rifles)’ and placed under the command of Lt. Col. Cyrus W. Peck (they were sometimes referred to unofficially as the ‘68th Prince Rupert Light Infantry).

In addition to this, a user on The Great War Forum apparently got in contact with an archivist in Prince Rupert itself and received this information.

The archivist at the Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives has been extremely helpful and supplied the following information:

"In 1909 Prince Rupert`s local militia was called the Muskeg Scouts" and later commissioned as the "Earl Grey`s Own Rifles" and authorized on May 1, 1910. On November 2, 1914 it was redesignated " 68th Regiment ( Earl Grey`s Own Rifles )" under the command of Lt. Col. Cyrus W. Peck.

In reference to the "Prince Rupert Light Infantry" - they are referring to the 68th Regiment that was redesignated on November 2. 1914. We Have newspaper articles that call the regiment the "68th Prince Rupert Light Infantry" but that was not it`s formal name."

The archivist has thus cleared up a mystery. " Muskeg Scouts" certainly has a romantic ring to the name. !!!

I also found some interesting photos of these "Muskeg Scouts", they provided a ceremonial bodyguard service to the Governor General of Canada, Albert Grey, 4th Earl Grey when he visited Prince Rupert on August 21, 1909. This is complete conjecture from myself but I would put forward that the Muskeg Scouts were formed sometime in 1909 and after the meeting with Earl Grey in August of that same year, they would have their name changed to reflect this connection in May of 1910. The photo above you shared in August of 1910 shows them in the process of working up to form into a more official looking and equipped unit. I would imagine many sources share the same confusion of wartime that we do now with units being reorganized and designated constantly. I would guess that whatever the unit had was rounded up and sent to Quebec, thereby renamed the 68th Regiment in November of 1914, leaving the unit name behind to train up more men for local defense/to be sent at a later date.

For the purposes of the story, I will be sticking with the Irish Fusiliers Regiment being the main defenders of Prince Rupert, supplemented by remnants of Earl Grey's Own Rifles. This all has been quite the interesting rabbit hole.

Strangely though, I found a copy of the Feb 9, 1915 edition of the Prince Rupert Journal saying the following:

68th Regt. Earl Grey's Own Rifles

Orders by Major J. H. Mc-Mullin, Commanding; for week ending Feb 13, 1915:

Parades: "A" company will parade at the Exhibition Building on Tuesday and Friday at 7:45pm, Drill squad and company. "B" company will parade at the Exhibition Building on Monday and Thursday at 7:45pm, Drill squad and company.

W.A. Pettigrew,

Captain, Acting Adjunct.

It would seem like additional units were continued to be stood up in Prince Rupert, perpetuating the same names and designations prior to being sent to Quebec for overseas duties? Or perhaps these units were kept at home for home defense? There is identical newspaper info blocks saying this same thing through 1915 and 1916.

This snippet was interesting as well and came from the the Prince Rupert Optimist paper of July 29, 1910.

EARL GREY'S RIFLES

Local Company of Militia Receives Its Allowance of Rifles

Captain Fred Stork, otherwise known as His Worship, has received from the department of militia the forty-two rifles to equip the militia company he formed here some time ago, and all they are now waiting for is the uniforms. An armory is to be established shortly and the company will start drilling. The company will use the ranges of the rifle association for target practice. A. W. Agnew is first lieutenant of the company and Stewart MeMordie second lieutenant.

From what I have seen researching over the weekend, Earl Grey's Own Rifles existed in some capacity as far back as 1910. The photo you shared is apparently their first parade according to some sources I have seen online, albeit without much of their military trousers and small arms. I have found the following with regard to the Earl Grey's as a unit at this obscure pdf.

In addition to this, a user on The Great War Forum apparently got in contact with an archivist in Prince Rupert itself and received this information.

I also found some interesting photos of these "Muskeg Scouts", they provided a ceremonial bodyguard service to the Governor General of Canada, Albert Grey, 4th Earl Grey when he visited Prince Rupert on August 21, 1909. This is complete conjecture from myself but I would put forward that the Muskeg Scouts were formed sometime in 1909 and after the meeting with Earl Grey in August of that same year, they would have their name changed to reflect this connection in May of 1910. The photo above you shared in August of 1910 shows them in the process of working up to form into a more official looking and equipped unit. I would imagine many sources share the same confusion of wartime that we do now with units being reorganized and designated constantly. I would guess that whatever the unit had was rounded up and sent to Quebec, thereby renamed the 68th Regiment in November of 1914, leaving the unit name behind to train up more men for local defense/to be sent at a later date.

For the purposes of the story, I will be sticking with the Irish Fusiliers Regiment being the main defenders of Prince Rupert, supplemented by remnants of Earl Grey's Own Rifles. This all has been quite the interesting rabbit hole.

Strangely though, I found a copy of the Feb 9, 1915 edition of the Prince Rupert Journal saying the following:

It would seem like additional units were continued to be stood up in Prince Rupert, perpetuating the same names and designations prior to being sent to Quebec for overseas duties? Or perhaps these units were kept at home for home defense? There is identical newspaper info blocks saying this same thing through 1915 and 1916.

This snippet was interesting as well and came from the the Prince Rupert Optimist paper of July 29, 1910.

Cool. I notice in the picture of the Muskeg Scouts in 1909, they do not seem to have their Ross Rifles yet. The guy in the back row looks to have a Lee-Enfield Mark 1 (cleaning rod visible where the Ross does not) and the guy nearest in the front row looks to have a lever action rifle.

The Battle of Digby Island

As with countless locations across Canada when hostilities were declared, Prince Rupert found itself left wanting with regard to its protection. The settlement's lackluster development throughout its early years would extend to its defense, consisting entirely of a small police presence until 1909 when a private citizen named John Beatty would establish the ‘Muskeg Scouts’. Named after the numerous bogs which surrounded the town, this ragtag group of locals were outfitted with an assortment of non-standard rifles alongside Stetson hats and neckerchiefs as their official uniform, although such an arrangement would prove to be short-lived. Following a visit from the Governor General of Canada, Earl Grey in August 1909, the unit adopted the title of ‘Earl Grey`s Own Rifles’ and would be authorized as an official Canadian Militia unit on May 1, 1910. While the unit was small with only a company sized force (Historians disagree about the size of a pre-war Canadian militia company and the overall size of the Earl Grey’s as a whole as documentation was poor in this period. Evidence points to the fact that the unit was likely around 50 men strong based on supply reports), it received proper uniforms, training and equipment provided by the Canadian government. This local unit would languish in relative unpopularity until August of 1914 where after the declaration of war, the unit would receive the prefix ‘68th Regiment’ and be ordered to reorganize into a four company unit. With the threat of invasion in British Columbia looming, Militia headquarters in Ottawa would realize that unit reorganization would be largely incomplete and additional manpower would be required to protect Prince Rupert.

The 11th Regiment Irish Fusiliers of Canada would be one of the many units assigned to local defense duties across the province shortly after the outbreak of war. Sporting an overall 440 men split into 8 companies, the force was relatively green, being formed in 1913 and under strength in comparison to its British counterparts. In a stroke of luck for the Canadians, the unit would come to gain a number of former British Army personnel in its ranks and by all accounts, the unit was well trained and equipped under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel George McSpadden. 55 men of ‘A Company’ and 8 men of the regiments Machine Gun Section would be deployed to Prince Rupert sometime prior to August 18, reinforcing what little remained of the Earl Grey`s Own Rifles already present. Stationed out of the Hotel Premier, soldiers would be present at the various pieces of local infrastructure to keep away saboteurs or raiders. Digby Island would prove a more challenging area to garrison. Located exposed to the sea on the entrance to Prince Rupert harbor, the station was a clear target for any enemy force sailing towards the town proper. The 4 acre property lended itself to being fairly defensible as the few dwellings present provided good avenues of fire both down towards the shore and out into the surrounding clearing. Frustratingly, accommodations on the island were limited to the point where even a small unit would put strain on the already cramped three operators and their families. It would eventually be decided that the regiment's Machine Gun Section would take up the task, led by Lieutenant Edward Bellew and consisting of a Corporal and 6 Privates. It was correctly surmised that if a larger unit could not be present, it would be wise to concentrate as much firepower in the defense of the installation as possible.

Men of the 11th Regiment Irish Fusiliers of Canada arriving in Prince Rupert, late in August of 1914.

Oberbootsmann Otto Achilles would command the 25 strong landing force, his pair of launches making landfall on Digby Island around 1910 hours. Considering the fact that this was one of the larger Canadian settlements in this area and the locals had shown a worrying propensity to throw their lives away in foolish acts, Achilles had taken one of Algerine’s .303 Maxim guns to mount aboard one of the launches. Such an armament would better allow them to fight their way ashore in the case of an opposed landing. Coming ashore away from the station's dock and tram line with little issue, the Germans pulled their boats up before leaving a trio of men behind to guard them. Faced with a march up highly sloped and forested terrain towards the station 100m above sea level, Oberbootsmann Achilles made the understandable decision to leave the cumbersome Maxim gun and its tripod behind. While the Germans moved inland to flank the property from the left side of the clearing, the station itself would receive a message from one of the merchants in Prince Rupert Harbor. A warship suspected of being a German raider had passed the station and was making its way into the harbor proper, this was to be passed onto the town proper. The young Private on watch had not reported such an event, being found shortly later by the unit's Corporal napping against the wireless office's outer wall. Wireless Operator Jack Bowerman would cautiously pass on the message to Prince Rupert, the surrounding stations and Lieutenant Bellew, unsure if this was yet another false alarm or an upcoming attack. The Lieutenant was far less willing to take the issue lightly, mustering the troops and preparing them for potential attack.

Operator Sid Jackson’s family resided in the main house on the property, sharing the building with the bachelors Fred Hollis and Jack Bowermen. When the Militia went to work setting up their M1895 Colt-Browning machine gun on the second floor, the off duty civilians preemptively sheltered in one of the properties outer sheds. The gun and its 3 man crew held a commanding presence over the property, able to reposition themselves throughout the building to reply to an attack from any angle. Another trio of men led by the Corporal took up direct defense of the wireless office itself while the remaining pair split up in the cutting itself, lying in wait amidst the maze of bushes, stumps and logs. In the tense minutes leading up to first contact, the station's black spaniel Paddy would break free from the arms of Sid Jackson's daughter, trouncing out through the property and almost catching fire from a twitchy Militiamen rifle. As fate would have it, the Canadians would not wait long for their battle. Upon reaching the cutting from the southwestern side, the Germans would split their ranks with one half providing cover from the tree line while the other would sneak towards the buildings. One of the detached Canadian sharpshooters would be the first to spot the enemy on their approach, a bayonet on one of the leading sailors' rifles glimmered in the evening sun. Having hid themselves in the hollowed out remains of a tall stump, the bark of the lone man's Ross rifle would kick off the skirmish at 1915. Quickly joined by his nearby partner, these two shooters would pin the exposed Germans down with a barrage of accurate and rapid fire. The landing party would suffer 1 dead and 1 injured before they could properly respond to the ambush, the sheer mass of the tree line covering forces rifle fire would put the Canadian sharpshooters temporarily on the back foot as they repositioned.

Likely not wishing to lose the initiative now that they were properly supported, Oberbootsmann Achilles rallied his men and ordered them to press their attack to the nearest structure. The Canadians would bring their remaining riflemen and machine gun into action around this time, catching the Germans halfway through their sprint in a hail of .303 caliber bullets. 3 more men would fall before the party made the cover of the smaller building, causing Canadian gunfire in their direction to stop entirely. The remaining 8 men moved to clear what they found to be a storage building, only to come face to face with operators Fred Hollis, Sid Jackson and the latter's family, laying flat on the floor. It would take little time for the Germans to realize that they had accidentally taken a number of human shields and placed both themselves alongside the civilians in a very hazardous situation. Both covering forces would continue to engage each other from their stationary positions until a door on the storage shed opened. Fred Hollis slowly walked out into the clearing holding up a stick with a white flour bag tied atop, gunfire would peter out as all participants observed another man carrying a child alongside a woman with a dog, their hands held high and following behind in short order. Running as quickly as they could to the backside of the property, both sides used the lull in fighting to take stock and reorganize. A German runner would be dispatched to retrieve their Maxim gun while Operator Bowermen would step away from the wireless equipment to provide first aid to Private Scott Wilkin who had been shot through both arms in the exchange. Once the 3 civilians had made the tree line and disappeared from sight, the engagement would continue in earnest.

View of the Digby Island wireless station from the water around the time of its establishment. The hastily cleared forest and steep incline can easily be seen from this photo.

After waiting for the machine gun to reload, Achilles would lead his unit on a second charge to bridge the gap and storm the wireless office. The Canadian defenders would shoot 2 more Germans dead on their approach but the remaining 6 attackers soon entered the structure and engaged in vicious room to room fighting. For the events which occurred in the next few minutes, Private Scott Wilkin would be posthumously awarded the first Victoria Cross of the action with the following citation.

“For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty. 19 August 1914, on Digby Island during an assault by a German landing party, Private Scott Wilkin was assigned to protect a strategically important building of the wireless station. In spite of being severely wounded in the arms, he continued to fight, holding the line with his comrades under heavy fire. When the enemy eventually overran their position and his commanding officer was killed, Wilkin engaged in hand to hand combat with the enemy. He would kill 3 of his opponents but would not survive the engagement himself. His gallant sacrifice would assist his allies in better resisting their foe .”

Oberbootsmann Achilles would be grazed multiple times in the exchange but the group would quickly take Operator Bowermen and the other injured but very much alive Canadian Private as prisoners. The wireless equipment inside was thoroughly destroyed using rifle butts, deck boots and a splitting axe found inside a nearby closet. With part of the defending force destroyed, the German covering force would use the lulls in machine gun fire to slowly but steadily advance through the clearing. The terrain was as much a blessing as a curse, large stumps and bushes provided cover and concealment yet they made any quick advance difficult. Both of the separate Canadian shooters would be forced to run for cover in the tree line as the enemy advanced and their ammunition ran low, the Germans using their superior numbers to split their fire between the two remaining Canadian sections. While Lieutenant Bellew’s machine gun continued to keep the bulk of the German force at arms reach, the loss of their comrades required the 3 man team to cover both avenues of attack at once. The Lieutenant would keep his rifle trained on the wireless office, exchanging sporadic fire with his German counterpart but keeping them stationary. Once the covering force had closed the distance significantly, they found themselves unable to move without catching accurate machine gun fire as 2 of their number would receive minor injuries at the end of the last move. All momentum would skid to a halt as the battle settled into minute after minute of a grueling stalemate, both combatants having locked the other in place with little options available to dislodge one another.

This deadlock would be unbroken until the arrival of 3 German sailors at 1930, lugging a Maxim gun, its tripod and the associated ammunition. Instead of circling back around through the forest, the group had taken a gamble, came up the beach and took the walkway up beside the station's tramline. This cut significant time off their hike and placed them in a perfect flanking position right on the property, something they took little time to exploit as the Canadians attention was squarely elsewhere. From the cover of the tram engine shed, the German machine gun would open fire on the main dwelling, soon joined by their comrades in pouring long swaths of fire into the structure's second story. When the Germans ceased fire to reload and move towards the buildings, they would find no return fire emanating throughout the property. Keeping their own machine gun aimed at the building, the Germans would finally come back together as a force and assess their situation. 10 of their own lay dead, almost all casualties came from the initial assaulting force. 1 man had suffered a gunshot wound to the arm while others had minor injuries due to shrapnel, grazing wounds and various other bumps and scrapes. After providing treatment to prisoners and their own men alike, the Germans quickly went to work preparing the facility for destruction. Similar to their strategy at Alert Bay, the sailors liberally covered the various buildings with gasoline from the generator building while others went to work felling the large stepped wooden masts. Likely not wishing to repeat another close quarters battle, the Germans would give a few shouts for any occupants to surrender towards the now quiet living quarters but with no reply, it too was prepared to be burnt.

A Canadian machine gun section moving their Colt-Browning M1895 alongside its tripod and ammunition during a training exercise. Machine guns in service at the outbreak of war were generally very cumbersome and required a crew to properly use.

Unknown to the attackers, Lieutenant Bellew and his assistant gunner had survived the barrage although not unscathed. While the Private had partially lost his eyesight and been shot through both the shoulder and the calf, Lieutenant Bellew was mortally wounded by a gunshot through the thigh and femur. Even with this injury, the officer's following actions would result in him being awarded the second Victoria Cross of the engagement.

"For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty. 19 August 1914, on Digby Island during an assault by a German landing party. Lieutenant Edward Bellew, as Company Machine Gun Officer, had one gun in action in a structure overlooking the facility. The enemy launched a surprise attack with superior force in the evening against the location. After a spirited defense, the adjacent unit covering one flank was soon put out of action, but the advance was temporarily stayed by Bellew, who both kept command of his gun and personally took a rifle to pin a separate enemy unit in place. After being flanked and attacked by an enemy machine gun, Lieutenant Bellew would be seriously injured alongside his gun being temporarily put out of action. Even with his injuries, Bellew showed little regard for his own safety as he provided medical attention to his surviving subordinate before repositioning his machine gun against the enemy. Fighting it out until the end, Bellew would succeed in further damaging the German gun position before he himself would be killed in action. His meritorious conduct and steadfast leadership throughout the battle would be a deciding factor in its outcome.”

The decision to not properly sweep the building would come back to haunt the Germans as Lieutenant Bellew would make his final stand. In one final act of defiance, the wounded officer would single handedly reposition and man the weapon, suffering serious burns from the hot weapon in the process. A burst of fire from his weapon would catch the inexperienced German gunners off guard, injuring 2 men and badly holing the Maxim guns water jacket before the enemy could properly respond. The Canadian would not survive the encounter although the commotion would provide enough of a distraction for the surviving Private to escape the residence building and hide in the clearing. The same mistake would not be made again and after confirming the buildings defenders had been well and truly neutralized, matches were lit and property began to be enveloped in a blaze. Before the Germans could fully gather their injured, prisoners and dead prior to departing at 1945, the Canadians would mount a surprise attack of their own. After fleeing into the nearby woods, the civilian staff of the station had run over a mile to take shelter at the nearby Department of Marine and Fisheries depot at Dodge Cove. In a stroke of good fortune, a group of 4 Militiamen had been present at the depot to transfer some equipment to Prince Rupert but upon hearing the small arms fire coming from the direction of the wireless station, they would move to investigate. Shortly after meeting the fleeing civilians, they would pick up their pace and rendezvous with the pair of sharpshooters near the scene, reaching the station just in time to see the area engulfed in flames.

Being taken under fire again, the Germans were forced to expedite their operation and flee the area. Utilizing what covering fire they could get from their Maxim, the injured and prisoners were painstakingly evacuated down alongside the station's tram line. The Canadians would slowly but surely push forward as more and more of the enemy disappeared out of sight back towards the beach. The valiant rear guard action of the German machine gun unit would largely be successful in holding the Canadians back until their comrades could retreat; however, the battle damage suffered to their guns' water jacket would eventually render it inoperable and require a fighting retreat. Contact would be broken after the Germans smashed their gun, the Canadians moved in to try and put out the fire alongside searching for survivors, the Germans would take shelter in the nearby forest to nurse their wounds and hopefully await retrieval by Algerine. While the Germans would succeed in their ultimate objective, it would come at a great cost in irreplaceable manpower. The Canadian government would attempt to turn the battle into a propaganda victory with a pair of Victoria Crosses eventually awarded and much media published about it, however many locals and members of the Militia would see through the rosy and sentimental retelling of the battle. The engagement would teach many valuable lessons to both sides this early in the war, the bloody and somewhat indecisive nature of the battle would foreshadow what many Canadians would find themselves witness to in the coming months throughout the fields of Europe.

sites.google.com

sites.google.com

The 11th Regiment Irish Fusiliers of Canada would be one of the many units assigned to local defense duties across the province shortly after the outbreak of war. Sporting an overall 440 men split into 8 companies, the force was relatively green, being formed in 1913 and under strength in comparison to its British counterparts. In a stroke of luck for the Canadians, the unit would come to gain a number of former British Army personnel in its ranks and by all accounts, the unit was well trained and equipped under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel George McSpadden. 55 men of ‘A Company’ and 8 men of the regiments Machine Gun Section would be deployed to Prince Rupert sometime prior to August 18, reinforcing what little remained of the Earl Grey`s Own Rifles already present. Stationed out of the Hotel Premier, soldiers would be present at the various pieces of local infrastructure to keep away saboteurs or raiders. Digby Island would prove a more challenging area to garrison. Located exposed to the sea on the entrance to Prince Rupert harbor, the station was a clear target for any enemy force sailing towards the town proper. The 4 acre property lended itself to being fairly defensible as the few dwellings present provided good avenues of fire both down towards the shore and out into the surrounding clearing. Frustratingly, accommodations on the island were limited to the point where even a small unit would put strain on the already cramped three operators and their families. It would eventually be decided that the regiment's Machine Gun Section would take up the task, led by Lieutenant Edward Bellew and consisting of a Corporal and 6 Privates. It was correctly surmised that if a larger unit could not be present, it would be wise to concentrate as much firepower in the defense of the installation as possible.

Men of the 11th Regiment Irish Fusiliers of Canada arriving in Prince Rupert, late in August of 1914.

Oberbootsmann Otto Achilles would command the 25 strong landing force, his pair of launches making landfall on Digby Island around 1910 hours. Considering the fact that this was one of the larger Canadian settlements in this area and the locals had shown a worrying propensity to throw their lives away in foolish acts, Achilles had taken one of Algerine’s .303 Maxim guns to mount aboard one of the launches. Such an armament would better allow them to fight their way ashore in the case of an opposed landing. Coming ashore away from the station's dock and tram line with little issue, the Germans pulled their boats up before leaving a trio of men behind to guard them. Faced with a march up highly sloped and forested terrain towards the station 100m above sea level, Oberbootsmann Achilles made the understandable decision to leave the cumbersome Maxim gun and its tripod behind. While the Germans moved inland to flank the property from the left side of the clearing, the station itself would receive a message from one of the merchants in Prince Rupert Harbor. A warship suspected of being a German raider had passed the station and was making its way into the harbor proper, this was to be passed onto the town proper. The young Private on watch had not reported such an event, being found shortly later by the unit's Corporal napping against the wireless office's outer wall. Wireless Operator Jack Bowerman would cautiously pass on the message to Prince Rupert, the surrounding stations and Lieutenant Bellew, unsure if this was yet another false alarm or an upcoming attack. The Lieutenant was far less willing to take the issue lightly, mustering the troops and preparing them for potential attack.

Operator Sid Jackson’s family resided in the main house on the property, sharing the building with the bachelors Fred Hollis and Jack Bowermen. When the Militia went to work setting up their M1895 Colt-Browning machine gun on the second floor, the off duty civilians preemptively sheltered in one of the properties outer sheds. The gun and its 3 man crew held a commanding presence over the property, able to reposition themselves throughout the building to reply to an attack from any angle. Another trio of men led by the Corporal took up direct defense of the wireless office itself while the remaining pair split up in the cutting itself, lying in wait amidst the maze of bushes, stumps and logs. In the tense minutes leading up to first contact, the station's black spaniel Paddy would break free from the arms of Sid Jackson's daughter, trouncing out through the property and almost catching fire from a twitchy Militiamen rifle. As fate would have it, the Canadians would not wait long for their battle. Upon reaching the cutting from the southwestern side, the Germans would split their ranks with one half providing cover from the tree line while the other would sneak towards the buildings. One of the detached Canadian sharpshooters would be the first to spot the enemy on their approach, a bayonet on one of the leading sailors' rifles glimmered in the evening sun. Having hid themselves in the hollowed out remains of a tall stump, the bark of the lone man's Ross rifle would kick off the skirmish at 1915. Quickly joined by his nearby partner, these two shooters would pin the exposed Germans down with a barrage of accurate and rapid fire. The landing party would suffer 1 dead and 1 injured before they could properly respond to the ambush, the sheer mass of the tree line covering forces rifle fire would put the Canadian sharpshooters temporarily on the back foot as they repositioned.

Likely not wishing to lose the initiative now that they were properly supported, Oberbootsmann Achilles rallied his men and ordered them to press their attack to the nearest structure. The Canadians would bring their remaining riflemen and machine gun into action around this time, catching the Germans halfway through their sprint in a hail of .303 caliber bullets. 3 more men would fall before the party made the cover of the smaller building, causing Canadian gunfire in their direction to stop entirely. The remaining 8 men moved to clear what they found to be a storage building, only to come face to face with operators Fred Hollis, Sid Jackson and the latter's family, laying flat on the floor. It would take little time for the Germans to realize that they had accidentally taken a number of human shields and placed both themselves alongside the civilians in a very hazardous situation. Both covering forces would continue to engage each other from their stationary positions until a door on the storage shed opened. Fred Hollis slowly walked out into the clearing holding up a stick with a white flour bag tied atop, gunfire would peter out as all participants observed another man carrying a child alongside a woman with a dog, their hands held high and following behind in short order. Running as quickly as they could to the backside of the property, both sides used the lull in fighting to take stock and reorganize. A German runner would be dispatched to retrieve their Maxim gun while Operator Bowermen would step away from the wireless equipment to provide first aid to Private Scott Wilkin who had been shot through both arms in the exchange. Once the 3 civilians had made the tree line and disappeared from sight, the engagement would continue in earnest.

View of the Digby Island wireless station from the water around the time of its establishment. The hastily cleared forest and steep incline can easily be seen from this photo.

After waiting for the machine gun to reload, Achilles would lead his unit on a second charge to bridge the gap and storm the wireless office. The Canadian defenders would shoot 2 more Germans dead on their approach but the remaining 6 attackers soon entered the structure and engaged in vicious room to room fighting. For the events which occurred in the next few minutes, Private Scott Wilkin would be posthumously awarded the first Victoria Cross of the action with the following citation.

“For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty. 19 August 1914, on Digby Island during an assault by a German landing party, Private Scott Wilkin was assigned to protect a strategically important building of the wireless station. In spite of being severely wounded in the arms, he continued to fight, holding the line with his comrades under heavy fire. When the enemy eventually overran their position and his commanding officer was killed, Wilkin engaged in hand to hand combat with the enemy. He would kill 3 of his opponents but would not survive the engagement himself. His gallant sacrifice would assist his allies in better resisting their foe .”

Oberbootsmann Achilles would be grazed multiple times in the exchange but the group would quickly take Operator Bowermen and the other injured but very much alive Canadian Private as prisoners. The wireless equipment inside was thoroughly destroyed using rifle butts, deck boots and a splitting axe found inside a nearby closet. With part of the defending force destroyed, the German covering force would use the lulls in machine gun fire to slowly but steadily advance through the clearing. The terrain was as much a blessing as a curse, large stumps and bushes provided cover and concealment yet they made any quick advance difficult. Both of the separate Canadian shooters would be forced to run for cover in the tree line as the enemy advanced and their ammunition ran low, the Germans using their superior numbers to split their fire between the two remaining Canadian sections. While Lieutenant Bellew’s machine gun continued to keep the bulk of the German force at arms reach, the loss of their comrades required the 3 man team to cover both avenues of attack at once. The Lieutenant would keep his rifle trained on the wireless office, exchanging sporadic fire with his German counterpart but keeping them stationary. Once the covering force had closed the distance significantly, they found themselves unable to move without catching accurate machine gun fire as 2 of their number would receive minor injuries at the end of the last move. All momentum would skid to a halt as the battle settled into minute after minute of a grueling stalemate, both combatants having locked the other in place with little options available to dislodge one another.

This deadlock would be unbroken until the arrival of 3 German sailors at 1930, lugging a Maxim gun, its tripod and the associated ammunition. Instead of circling back around through the forest, the group had taken a gamble, came up the beach and took the walkway up beside the station's tramline. This cut significant time off their hike and placed them in a perfect flanking position right on the property, something they took little time to exploit as the Canadians attention was squarely elsewhere. From the cover of the tram engine shed, the German machine gun would open fire on the main dwelling, soon joined by their comrades in pouring long swaths of fire into the structure's second story. When the Germans ceased fire to reload and move towards the buildings, they would find no return fire emanating throughout the property. Keeping their own machine gun aimed at the building, the Germans would finally come back together as a force and assess their situation. 10 of their own lay dead, almost all casualties came from the initial assaulting force. 1 man had suffered a gunshot wound to the arm while others had minor injuries due to shrapnel, grazing wounds and various other bumps and scrapes. After providing treatment to prisoners and their own men alike, the Germans quickly went to work preparing the facility for destruction. Similar to their strategy at Alert Bay, the sailors liberally covered the various buildings with gasoline from the generator building while others went to work felling the large stepped wooden masts. Likely not wishing to repeat another close quarters battle, the Germans would give a few shouts for any occupants to surrender towards the now quiet living quarters but with no reply, it too was prepared to be burnt.

A Canadian machine gun section moving their Colt-Browning M1895 alongside its tripod and ammunition during a training exercise. Machine guns in service at the outbreak of war were generally very cumbersome and required a crew to properly use.

Unknown to the attackers, Lieutenant Bellew and his assistant gunner had survived the barrage although not unscathed. While the Private had partially lost his eyesight and been shot through both the shoulder and the calf, Lieutenant Bellew was mortally wounded by a gunshot through the thigh and femur. Even with this injury, the officer's following actions would result in him being awarded the second Victoria Cross of the engagement.

"For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty. 19 August 1914, on Digby Island during an assault by a German landing party. Lieutenant Edward Bellew, as Company Machine Gun Officer, had one gun in action in a structure overlooking the facility. The enemy launched a surprise attack with superior force in the evening against the location. After a spirited defense, the adjacent unit covering one flank was soon put out of action, but the advance was temporarily stayed by Bellew, who both kept command of his gun and personally took a rifle to pin a separate enemy unit in place. After being flanked and attacked by an enemy machine gun, Lieutenant Bellew would be seriously injured alongside his gun being temporarily put out of action. Even with his injuries, Bellew showed little regard for his own safety as he provided medical attention to his surviving subordinate before repositioning his machine gun against the enemy. Fighting it out until the end, Bellew would succeed in further damaging the German gun position before he himself would be killed in action. His meritorious conduct and steadfast leadership throughout the battle would be a deciding factor in its outcome.”

The decision to not properly sweep the building would come back to haunt the Germans as Lieutenant Bellew would make his final stand. In one final act of defiance, the wounded officer would single handedly reposition and man the weapon, suffering serious burns from the hot weapon in the process. A burst of fire from his weapon would catch the inexperienced German gunners off guard, injuring 2 men and badly holing the Maxim guns water jacket before the enemy could properly respond. The Canadian would not survive the encounter although the commotion would provide enough of a distraction for the surviving Private to escape the residence building and hide in the clearing. The same mistake would not be made again and after confirming the buildings defenders had been well and truly neutralized, matches were lit and property began to be enveloped in a blaze. Before the Germans could fully gather their injured, prisoners and dead prior to departing at 1945, the Canadians would mount a surprise attack of their own. After fleeing into the nearby woods, the civilian staff of the station had run over a mile to take shelter at the nearby Department of Marine and Fisheries depot at Dodge Cove. In a stroke of good fortune, a group of 4 Militiamen had been present at the depot to transfer some equipment to Prince Rupert but upon hearing the small arms fire coming from the direction of the wireless station, they would move to investigate. Shortly after meeting the fleeing civilians, they would pick up their pace and rendezvous with the pair of sharpshooters near the scene, reaching the station just in time to see the area engulfed in flames.

Being taken under fire again, the Germans were forced to expedite their operation and flee the area. Utilizing what covering fire they could get from their Maxim, the injured and prisoners were painstakingly evacuated down alongside the station's tram line. The Canadians would slowly but surely push forward as more and more of the enemy disappeared out of sight back towards the beach. The valiant rear guard action of the German machine gun unit would largely be successful in holding the Canadians back until their comrades could retreat; however, the battle damage suffered to their guns' water jacket would eventually render it inoperable and require a fighting retreat. Contact would be broken after the Germans smashed their gun, the Canadians moved in to try and put out the fire alongside searching for survivors, the Germans would take shelter in the nearby forest to nurse their wounds and hopefully await retrieval by Algerine. While the Germans would succeed in their ultimate objective, it would come at a great cost in irreplaceable manpower. The Canadian government would attempt to turn the battle into a propaganda victory with a pair of Victoria Crosses eventually awarded and much media published about it, however many locals and members of the Militia would see through the rosy and sentimental retelling of the battle. The engagement would teach many valuable lessons to both sides this early in the war, the bloody and somewhat indecisive nature of the battle would foreshadow what many Canadians would find themselves witness to in the coming months throughout the fields of Europe.

Irish Regiments of the Empire - Canadian Irish Regiments

A number of Canadian Irish rifle companies had been established in the 19th century, as part of the Canadian Militia. The Irish Royals were formed at Saint John New Brunswick. In Lower Canada, a company of Irish Rifles were formed at Montreal in 1837. A Royal Irish Company at Quebec in 1837.

I'm assuming those are the first VC's awarded to Canadians in the war. possibly the first VC's in the war period.

Edit: Yeah, just checked the first VC was awarded on August 23. beat them by 4 days.

Edit: Yeah, just checked the first VC was awarded on August 23. beat them by 4 days.

Last edited:

Coulsdon Eagle

Monthly Donor

Yes, Mons - Godley & Dease.I'm assuming those are the first VC's awarded to Canadians in the war. possibly the first VC's in the war period.

Edit: Yeah, just checked the first VC was awarded on August 23. beat them by 4 days.

Depending on if other men end up getting nominated for the VC, the first award of the war for a Canadian and more broadly for the Empire as a whole could go as far back as August 11 when HMCS Rainbow engaged SMS Leipzig off San Francisco. There is also the conduct of the various Militiamen, Sailors, Submariners and many other more prior to these events which may bear fruit in future chapters. I won't give a definite answer as these may or may not involve spoilers but I am keeping track behind the scenes.I'm assuming those are the first VC's awarded to Canadians in the war. possibly the first VC's in the war period.

Edit: Yeah, just checked the first VC was awarded on August 23. beat them by 4 days.

It also depends if one counts a Canadian VC as being won by somebody fighting for Canada or won by a born and raised Canadian, as Bellew and many other men both here and in our own timeline had moved to Canada prior to the outbreak of the war. Not that I largely care either way but I've seen people make the distinction elsewhere.

Last edited:

Hopefully the trend of the Canadians fighting back like this will continue. Sounds like there might be a glut of Victoria Crosses awarded for all of these events, I wonder if Britain will ultimately approve them or if they will butt heads with the Canadians? I think I remember this happening a few times historically with some of the Commonwealth.

Share: